Content delivery network

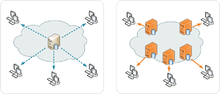

(Right) CDN scheme of distribution

A content delivery network or content distribution network (CDN) is a geographically distributed network of proxy servers and their data centers. The goal is to distribute service spatially relative to end-users to provide high availability and high performance. CDNs serve a large portion of the Internet content today, including web objects (text, graphics and scripts), downloadable objects (media files, software, documents), applications (e-commerce, portals), live streaming media, on-demand streaming media, and social media sites.

CDNs are a layer in the internet ecosystem. Content owners such as media companies and e-commerce vendors pay CDN operators to deliver their content to their end users. In turn, a CDN pays ISPs, carriers, and network operators for hosting its servers in their data centers.

CDN is an umbrella term spanning different types of content delivery services: video streaming, software downloads, web and mobile content acceleration, licensed/managed CDN, transparent caching, and services to measure CDN performance, load balancing, multi-CDN switching and analytics and cloud intelligence. CDN vendors may cross over into other industries like security, with DDoS protection and web application firewalls (WAF), and WAN optimization.

Technology

CDN nodes are usually deployed in multiple locations, often over multiple backbones. Benefits include reducing bandwidth costs, improving page load times, or increasing global availability of content. The number of nodes and servers making up a CDN varies, depending on the architecture, some reaching thousands of nodes with tens of thousands of servers on many remote points of presence (PoPs). Others build a global network and have a small number of geographical PoPs.[1]

Requests for content are typically algorithmically directed to nodes that are optimal in some way. When optimizing for performance, locations that are best for serving content to the user may be chosen. This may be measured by choosing locations that are the fewest hops, the least number of network seconds away from the requesting client, or the highest availability in terms of server performance (both current and historical), so as to optimize delivery across local networks. When optimizing for cost, locations that are least expensive may be chosen instead. In an optimal scenario, these two goals tend to align, as edge servers that are close to the end-user at the edge of the network may have an advantage in performance or cost.

Most CDN providers will provide their services over a varying, defined, set of PoPs, depending on the coverage desired, such as United States, International or Global, Asia-Pacific, etc. These sets of PoPs can be called "edges", "edge nodes" or "edge networks" as they would be the closest edge of CDN assets to the end user.[2]

The CDN's Edge Network grows outward from the origins through further acquisitions (via purchase, peering, or exchange) of co-locations facilities, bandwidth, and servers.

Content networking techniques

The Internet was designed according to the end-to-end principle.[3] This principle keeps the core network relatively simple and moves the intelligence as much as possible to the network end-points: the hosts and clients. As a result, the core network is specialized, simplified, and optimized to only forward data packets.

Content Delivery Networks augment the end-to-end transport network by distributing on it a variety of intelligent applications employing techniques designed to optimize content delivery. The resulting tightly integrated overlay uses web caching, server-load balancing, request routing, and content services.[4] These techniques are briefly described below.

Web caches store popular content on servers that have the greatest demand for the content requested. These shared network appliances reduce bandwidth requirements, reduce server load, and improve the client response times for content stored in the cache. Web caches are populated based on requests from users (pull caching) or based on preloaded content disseminated from content servers (push caching).[5]

Server-load balancing uses one or more techniques including service-based (global load balancing) or hardware-based, i.e. layer 4–7 switches, also known as a web switch, content switch, or multilayer switch to share traffic among a number of servers or web caches. Here the switch is assigned a single virtual IP address. Traffic arriving at the switch is then directed to one of the real web servers attached to the switch. This has the advantage of balancing load, increasing total capacity, improving scalability, and providing increased reliability by redistributing the load of a failed web server and providing server health checks.

A content cluster or service node can be formed using a layer 4–7 switch to balance load across a number of servers or a number of web caches within the network.

Request routing directs client requests to the content source best able to serve the request. This may involve directing a client request to the service node that is closest to the client, or to the one with the most capacity. A variety of algorithms are used to route the request. These include Global Server Load Balancing, DNS-based request routing, Dynamic metafile generation, HTML rewriting,[6] and anycasting.[7] Proximity—choosing the closest service node—is estimated using a variety of techniques including reactive probing, proactive probing, and connection monitoring.[4]

CDNs use a variety of methods of content delivery including, but not limited to, manual asset copying, active web caches, and global hardware load balancers.

Content service protocols

Several protocol suites are designed to provide access to a wide variety of content services distributed throughout a content network. The Internet Content Adaptation Protocol (ICAP) was developed in the late 1990s[8][9] to provide an open standard for connecting application servers. A more recently defined and robust solution is provided by the Open Pluggable Edge Services (OPES) protocol.[10] This architecture defines OPES service applications that can reside on the OPES processor itself or be executed remotely on a Callout Server. Edge Side Includes or ESI is a small markup language for edge level dynamic web content assembly. It is fairly common for websites to have generated content. It could be because of changing content like catalogs or forums, or because of the personalization. This creates a problem for caching systems. To overcome this problem, a group of companies created ESI.

Peer-to-peer CDNs

In peer-to-peer (P2P) content-delivery networks, clients provide resources as well as use them. This means that unlike client-server systems, the content centric networks can actually perform better as more users begin to access the content (especially with protocols such as Bittorrent that require users to share). This property is one of the major advantages of using P2P networks because it makes the setup and running costs very small for the original content distributor.[11][12]

Private CDNs

If content owners are not satisfied with the options or costs of a commercial CDN service, they can create their own CDN. This is called a private CDN. A private CDN consists of POPs (points of presence) that are only serving content for their owner. These POPs can be caching servers,[13] reverse proxies or application delivery controllers.[14] It can be as simple as two caching servers,[13] or large enough to serve petabytes of content.[15]

Large content distribution networks may even build and set up their own private network to distribute copies of content across cache locations.[16][17] Such private networks are usually used in conjunction with public networks as a backup option in case the capacity of private network is not enough or there is a failure which leads to capacity reduction. Since the same content has to be distributed across many locations, a variety of multicasting techniques may be used to reduce bandwidth consumption. Over private networks, it has also been proposed to select multicast trees according to network load conditions to more efficiently utilize available network capacity.[18][19]

CDN trends

Emergence of telco CDNs

The rapid growth of streaming video traffic[20] uses large capital expenditures by broadband providers[21] in order to meet this demand and to retain subscribers by delivering a sufficiently good quality of experience.

To address this, telecommunications service providers (TSPs) have begun to launch their own content delivery networks as a means to lessen the demands on the network backbone and to reduce infrastructure investments.

Telco CDN advantages

Because they own the networks over which video content is transmitted, telco CDNs have advantages over traditional CDNs.

They own the last mile and can deliver content closer to the end user because it can be cached deep in their networks. This deep caching minimizes the distance that video data travels over the general Internet and delivers it more quickly and reliably.

Telco CDNs also have a built-in cost advantage since traditional CDNs must lease bandwidth from them and build the operator’s margin into their own cost model.

In addition, by operating their own content delivery infrastructure, telco operators have a better control over the utilization of their resources. Content management operations performed by CDNs are usually applied without (or with very limited) information about the network (e.g., topology, utilization etc.) of the telco-operators with which they interact or have business relationships. These pose a number of challenges for the telco-operators which have a limited sphere of actions in face of the impact of these operations on the utilization of their resources.

In contrast, the deployment of telco-CDNs allow operators to implement their own content management operations,[22][23] which enables them to have better control over the utilization of their resources and, as such, provide better quality of service and experience to their end users.

Federated CDNs

In June 2011, StreamingMedia.com reported that a group of TSPs had founded an Operator Carrier Exchange (OCX)[24] to interconnect their networks and compete more directly against large traditional CDNs like Akamai and Limelight Networks, which have extensive PoPs worldwide. This way, telcos are building a Federated CDN offering, which is more interesting for a content provider willing to deliver its content to the aggregated audience of this federation.

It is likely that in a near future, other telco CDN federations will be created. They will grow by enrollment of new telcos joining the federation and bringing network presence and their Internet subscriber bases to the existing ones.

edns-client-subnet EDNS0 option

In August 2011, a global consortium of leading Internet service providers led by Google announced their official implementation of the edns-client-subnet IETF Internet-Draft,[25] which is intended to accurately localize DNS resolution responses. The initiative involves a limited number of leading DNS and CDN service providers. With the edns-client-subnet EDNS0 option, the recursive DNS servers of CDNs will utilize the IP address of the requesting client subnet when resolving DNS requests. If a CDN relies on the IP address of the DNS resolver instead of the client when resolving DNS requests, it can incorrectly geo-locate a client if the client is using Google anycast addresses for their DNS resolver, which can create latency problems. Initially, Google's 8.8.8.8 DNS addresses geo-located to California, potentially far from the location of the requesting client, but now the Google Public DNS servers are available worldwide.[26]

Notable content delivery service providers

Free CDNs

Traditional commercial CDNs

- Akamai Technologies[27]

- Amazon CloudFront[27]

- Aryaka

- Azure CDN

- CacheFly

- CDNetworks[27]

- CenterServ[27]

- ChinaCache

- Cloudflare[27]

- Cotendo

- EdgeCast Networks

- Fastly

- Highwinds Network Group

- HP Cloud Services

- Incapsula

- Instart

- Internap

- LeaseWeb

- Level 3 Communications

- Limelight Networks

- MetaCDN

- NACEVI

- OnApp

- OVH

- Rackspace Cloud Files

- Speedera Networks

- StreamZilla

- Wangsu Science & Technology

- Webscale

- Yottaa

Telco CDNs

- AT&T Inc.

- Bharti Airtel

- Bell Canada

- BT Group

- CenturyLink

- China Telecom

- Deutsche Telekom

- KT

- KPN

- Level 3 Communications

- Megafon

- NTT

- Pacnet

- PCCW

- Qualitynet

- SingTel

- SK Broadband

- Tata Communications

- Telecom Argentina

- Telecom Italia

- Spark New Zealand

- Telefonica

- Telenor

- TeliaSonera

- Telin

- Telstra

- Telus

- Turk Telekom

- Verizon

Commercial CDNs using P2P for delivery

Multi CDNs

Generally speaking, all Internet service providers can provide a content delivery network.

See also

- Application software

- Bel Air Circuit

- Comparison of streaming media systems

- Comparison of video services

- Content delivery network interconnection

- Content delivery platform

- Data center

- Digital television

- Dynamic site acceleration

- Edge computing

- Internet radio

- Internet television

- IPTV

- List of music streaming services

- List of streaming media systems

- Multicast

- NetMind

- Open Music Model

- Over-the-top content

- P2PTV

- Protection of Broadcasts and Broadcasting Organizations Treaty

- Push technology

- Software as a service

- Streaming media

- Webcast

- Web syndication

- Web television

References

- ↑ "How Content Delivery Networks Work". CDNetworks. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ↑ "How content delivery networks (CDNs) work". NCZOnline. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ↑ Saltzer, J. H., Reed, D. P., Clark, D. D.: “End-to-End Arguments in System Design,” ACM Transactions on Communications, 2(4), 1984

- 1 2 Hofmann, Markus; Leland R. Beaumont (2005). Content Networking: Architecture, Protocols, and Practice. Morgan Kaufmann Publisher. ISBN 1-55860-834-6.

- ↑ Bestavros, Azer (March 1996). "Speculative Data Dissemination and Service to Reduce Server Load, Network Traffic and Service Time for Distributed Information Systems" (PDF). Proceedings of ICDE'96: The 1996 International Conference on Data Engineering. 1996: 180–189.

- ↑ RFC 3568 Barbir, A., Cain, B., Nair, R., Spatscheck, O.: "Known Content Network (CN) Request-Routing Mechanisms," July 2003

- ↑ RFC 1546 Partridge, C., Mendez, T., Milliken, W.: "Host Anycasting Services," November 1993.

- ↑ RFC 3507 Elson, J., Cerpa, A.: "Internet Content Adaptation Protocol (ICAP)," April 2003.

- ↑ ICAP Forum

- ↑ RFC 3835 Barbir, A., Penno, R., Chen, R., Hofmann, M., and Orman, H.: "An Architecture for Open Pluggable Edge Services (OPES)," August 2004.

- ↑ Li, Jin. "On peer-to-peer (P2P) content delivery" (PDF). Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications. 1 (1): 45–63. doi:10.1007/s12083-007-0003-1.

- ↑ Stutzbach, Daniel et al. (2005). "The scalability of swarming peer-to-peer content delivery". In Boutaba, Raouf et al. NETWORKING 2005 -- Networking Technologies, Services, and Protocols; Performance of Computer and Communication Networks; Mobile and Wireless Communications Systems (PDF). Springer. pp. 15–26. ISBN 978-3-540-25809-4.

- 1 2 "How to build your own CDN using BIND, GeoIP, Nginx, Varnish - UNIXy".

- ↑ "How to Create Your Content Delivery Network With aiScaler".

- ↑ "Netflix Shifts Traffic To Its Own CDN; Akamai, Limelight Shrs Hit". Forbes. 5 June 2012.

- ↑ Mikel Jimenez; et al. (May 1, 2017). "Building Express Backbone: Facebook's new long-haul network". Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ↑ "Inter-Datacenter WAN with centralized TE using SDN and OpenFlow" (PDF). 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ↑ M. Noormohammadpour; et al. (July 10, 2017). "DCCast: Efficient Point to Multipoint Transfers Across Datacenters". USENIX. Retrieved July 26, 2017.

- ↑ M. Noormohammadpour; et al. (2018). "QuickCast: Fast and Efficient Inter-Datacenter Transfers using Forwarding Tree Cohorts". Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Online Video Sees Tremendous Growth, Spurs some Major Updates". SiliconANGLE.

- ↑ "Overall Telecom CAPEX to Rise in 2011 Due to Video, 3G, LTE Investments". cellular-news.

- ↑ D. Tuncer, M. Charalambides, R. Landa, G. Pavlou, “More Control Over Network Resources: an ISP Caching Perspective,” proceedings of IEEE/IFIP Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM), Zurich, Switzerland, October 2013.

- ↑ M. Claeys, D. Tuncer, J. Famaey, M. Charalambides, S. Latre, F. De Turck, G. Pavlou, “Proactive Multi-tenant Cache Management for Virtualized ISP Networks,” proceedings of IEEE/IFIP Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, November 2014.

- ↑ "Telcos And Carriers Forming New Federated CDN Group Called OCX (Operator Carrier Exchange)". Dan Rayburn - StreamingMediaBlog.com.

- ↑ "Client Subnet in DNS Requests".

- ↑ "Where are your servers currently located?".

- 1 2 3 4 5 "How CDN and International Servers Networking Facilitate Globalization". The Huffington Post. Delarno Delvix. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

Further reading

- Buyya, R.; Pathan, M.; Vakali, A. (2008). Content Delivery Networks. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77887-5_1. ISBN 9783540778868.

- Hau, T.; Burghardt, D.; Brenner, W. (2011). "Multihoming, Content Delivery Networks, and the Market for Internet Connectivity". Telecommunications Policy. 35 (6): 532–542. doi:10.1016/j.telpol.2011.04.002.

- Majumdar, S.; Kulkarni, D.; Ravishankar, C. (2007). "Addressing Click Fraud in Content Delivery Systems" (PDF). Infocom. IEEE. doi:10.1109/INFCOM.2007.36.

- Nygren., E.; Sitaraman R. K.; Sun, J. (2010). "The Akamai Network: A Platform for High-Performance Internet Applications" (PDF). ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review. 44 (3): 2–19. doi:10.1145/1842733.1842736. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- Vakali, A.; Pallis, G. (2003). "Content Delivery Networks: Status and Trends". IEEE Internet Computing. 7 (6): 68–74. doi:10.1109/MIC.2003.1250586.