Steam (software)

|

| |

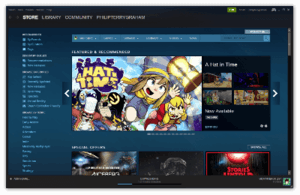

Steam in October 2017, showing the storefront page | |

| Developer(s) | Valve Corporation |

|---|---|

| Initial release | September 11, 2003 |

| Stable release | API v018, Package 1539393410 (October 12, 2018) [±] |

| Preview release | API v018, Package: 1539216652 (October 11, 2018) [±] |

| Platform | |

| Available in | 28[1] languages |

|

List of languages English, Brazilian Portuguese, Bulgarian, Chinese (Simplified), Chinese (Traditional), Czech, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, French, Greek, German, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latin American Spanish, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Romanian, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, Turkish, Ukrainian, Vietnamese | |

| Type | |

| License | Proprietary software |

| Alexa rank |

|

| Website | store.steampowered.com |

Steam is a digital distribution platform for video games developed by Valve Corporation that offers digital rights management (DRM), matchmaking servers, video streaming, and social networking services. Steam provides the user with installation and automatic updating of games, and community features such as friends lists and groups, cloud saving, and in-game voice and chat functionality.

The software provides a freely available application programming interface (API) called Steamworks, which developers can use to integrate many of Steam's functions into their products, including networking, matchmaking, in-game achievements, microtransactions, and support for user-created content through Steam Workshop. Though initially developed for use on Microsoft Windows operating systems, versions for macOS and Linux were later released. Mobile apps with connected functionality with the main software were later released for iOS, Android, and Windows Phone in the 2010s. The platform also offers a small selection of non-video game content, such as design software, anime, and films.

The Steam platform is the largest digital distribution platform for PC gaming, estimated in 2013 to have 75% of the market space.[4] By 2017, users purchasing games through Steam totaled roughly US$4.3 billion, representing at least 18% of global PC game sales.[5] By early 2018, the service had over 150 million registered accounts with a peak of 18.5 million concurrent users online. The success of the Steam platform has led to the development of a line of Steam Machine microconsoles, as well as the SteamOS operating system.

History

| 2002 | Announcement and beta release |

| 2003 | Official release |

| 2004 | |

| 2005 | First publisher partnership |

| 2006 | |

| 2007 | Steam Community launched |

| 2008 | Steamworks released |

| Matchmaking released | |

| 2009 | Steam Cloud |

| 2010 | Mac OS X client released |

| Translation Server opened | |

| 2011 | Steam Workshop launched |

| 2012 | Steam mobile apps released |

| Steam for Schools launched | |

| Steam Greenlight launched | |

| Big Picture Mode launched | |

| Productivity software added to catalog | |

| 2013 | Linux client released |

| Family Sharing launched | |

| 2014 | In-Home Streaming launched |

| Steam Music launched | |

| Discovery 1.0 update | |

| 2015 | Broadcast streaming launched |

| Steam Hardware/SteamOS | |

| Steam Machines released | |

| Movies/TV purchases/renting added to library | |

| 2016 | SteamVR launched |

| Discovery 2.0 update launched | |

| 2017 | Steam Direct launched |

| 2018 | Steam.tv launched |

Before implementing Steam, Valve Corporation had problems updating its online games, such as Counter-Strike; providing patches would result in most of the online user base disconnecting for several days. Valve decided to create a platform that would update games automatically and implement stronger anti-piracy and anti-cheat measures. Through user polls at the time of its announcement in 2002, Valve also recognized that at least 75% of their users had access to high-speed Internet connections, which would only grow with planned Internet expansion in the following years, and recognized that they could deliver game content faster to players than through retail channels.[6] Valve approached several companies, including Microsoft, Yahoo!, and RealNetworks to build a client with these features, but were declined.[7]

Steam's development began in 2002, with working titles for the platform being "Grid" and "Gazelle".[8][9] It was publicly announced at the Game Developers Conference event on March 22, 2002, and released as a beta the same day.[10][11] To demonstrate the ease of integrating Steam with a game, Relic Entertainment created a special version of Impossible Creatures.[12] Valve partnered with several companies, including AT&T, Acer, and GameSpy. The first mod released on the system was Day of Defeat.[13]

Between 80,000–300,000 players participated in the beta client before its official release on September 11, 2003, for which it was mandatory to use with Counter-Strike version 1.6.[13][14][8][15][16][17] The client and website choked under the strain of thousands of users simultaneously attempting to play the game.[18] At the time, Steam's primary function was streamlining the patch process common in online computer games, and was an optional component for all other games. In 2004, the World Opponent Network was shut down and replaced by Steam, with any online features of games that required it ceasing to work unless they converted over to Steam.[19]

Around that time, Valve began negotiating contracts with several publishers and independent developers to release their products, including Rag Doll Kung Fu and Darwinia, on Steam. Canadian publisher Strategy First announced in December 2005 that it would partner with Valve for digital distribution of current and future titles.[20] In 2002, the managing director of Valve, Gabe Newell, said he was offering mod teams a game engine license and distribution over Steam for US$995.[13] Valve's Half-Life 2 was the first game to require installation of the Steam client to play, even for retail copies. This decision was met with concerns about software ownership, software requirements, and issues with overloaded servers demonstrated previously by the Counter-Strike rollout.[21] During this time users faced multiple issues attempting to play the game.[8][22][23]

Beginning with Rag Doll Kung Fu in October 2005, third-party games became available for purchase and download on Steam,[24] and Valve announced that Steam had become profitable because of some highly successful Valve games. Although digital distribution could not yet match retail volume, profit margins for Valve and developers were far larger on Steam.[25] Large developer-publishers, including id Software,[26] Eidos Interactive,[27] and Capcom,[28] began distributing their games on Steam in 2007. By May of that year, 13 million accounts had been created on the service, and 150 games were for sale on the platform.[29][30] By 2014, total annual game sales on Steam were estimated at around $1.5 billion.[31] Since 2007, Valve has continued to expand Steam's functionality and services for consumers and developers.

Client functionality

Software delivery and maintenance

Steam's primary service is to allow its users to download games and other software that they have in their virtual software libraries to their local computers as game cache files (GCFs).[32] Initially, Valve was required to be the publisher for these titles since they had sole access to the Steam's database and engine, but with the introduction of the Steamworks software development kit (SDK) in May 2008, anyone could potentially become a publisher to Steam, outside of Valve's involvement to curate titles on the service.[33]

Prior to 2009, most games released on Steam had traditional anti-piracy measures, including the assignment and distribution of product keys and support for digital rights management software tools such as SecuROM or non-malicious rootkits. With an update to the Steamworks SDK in March 2009, Valve added its "Custom Executable Generation" (CEG) approach into the Steamworks SDK that removed the need for these other measures. The CEG technology creates a unique, encrypted copy of the game's executable files for the given user, which allows them to install it multiple times and on multiple devices, and make backup copies of their software.[34] Once the software is downloaded and installed, the user must then authenticate through Steam to de-encrypt the executable files to play the game. Normally this is done while connected to the Internet following the user's credential validation, but once they have logged into Steam once, a user can instruct Steam to launch in a special offline mode to be able to play their games without a network connection.[35][36] Developers are not limited to Steam's CEG and may include other forms of DRM and other authentication services than Steam; for example, some titles from publisher Ubisoft require the use of their UPlay gaming service,[37] and prior to its shutdown in 2014, some other titles required Games for Windows – Live, though many of these titles have since transitioned to using the Steamworks CEG approach.[38]

In September 2008, Valve added support for Steam Cloud, a service that can automatically store saved game and related custom files on Valve's servers; users can access this data from any machine running the Steam client.[39] Games must use the appropriate features of Steamworks for Steam Cloud to work. Users can disable this feature on a per-game and per-account basis.[40] In May 2012, the service added the ability for users to manage their game libraries from remote clients, including computers and mobile devices; users can instruct Steam to download and install games they own through this service if their Steam client is currently active and running.[41] Some games sold through retail channels can be redeemed as titles for users' libraries within Steam by entering a product code within the software.[42] For games that incorporate Steamworks, users can buy redemption codes from other vendors and redeem these in the Steam client to add the title to their libraries. Steam also offers a framework for selling and distributing downloadable content (DLC) for games.[43][44]

In September 2013, Steam introduced the ability to share most games with family members and close friends by authorizing machines to access one's library. Authorized players can install the game locally and play it separately from the owning account. Users can access their saved games and achievements providing the main owner is not playing. When the main player initiates a game while a shared account is using it, the shared account user is allowed a few minutes to either save their progress and close the game or purchase the game for his or her own account.[45] Within Family View, introduced in January 2014, parents can adjust settings for their children's tied accounts, limiting the functionality and accessibility to the Steam client and purchased titles.[46]

In accordance with its Acceptable Use Policy, Valve retains the right to block and unblock customers' access to their games and Steam services when Valve's Anti-Cheat (VAC) software determines that the user is cheating in multiplayer games, selling accounts to others or trading games to exploit regional price differences.[47] Blocking such users initially removed access to his or her other games, leading to some users with high-value accounts losing access because of minor infractions of the AUP.[48] Valve later changed its policy to be similar to that of Electronic Arts' Origin platform, in which blocked users can still access their games but are heavily restricted, limited to playing in offline mode and unable to participate in Steam Community features.[49] Customers also lose access to their games and Steam account if they refuse to accept changes to Steam's end user license agreements; this occurred in August 2012.[50] In April 2015, Valve began allowing developers to set bans on players for their games, but enacted and enforced at the Steam level, which allowed them to police their own gaming communities in customizable manner.[51]

Storefront features

The Steam client includes a digital storefront called the Steam Store through which users can purchase computer games. Once the game is bought, a software license is permanently attached to the user's Steam account, allowing him or her to download the software on any compatible device. Game licenses can be given to other accounts under certain conditions. Content is delivered from an international network of servers using a proprietary file transfer protocol.[52] Steam sells its products in US and Canadian dollars, euros, pounds sterling, Brazilian reais, Russian rubles, Indonesian rupiah and Indian rupees[53] depending on the user's location.[54] From December 2010, the client supports the WebMoney payment system, which is popular in many European, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries.[55] Starting in April 2016, Steam began accepting payments in Bitcoin, valued based on the user's geolocation, with transactions handled by BitPay.[56] However, Valve dropped the ability to use Bitcoin in December 2017, citing high fluctuation in value and costly service fees that made its use "untenable".[57] The Steam storefront validates the user's region; the purchase of titles may be restricted to specific regions because of release dates, game classification, or agreements with publishers. Since 2010, the Steam Translation Server project offers Steam users to assist with the translation of the Steam client, storefront, and a selected library of Steam games for twenty-seven languages.[58] Steam also allows users to purchase downloadable content for games, and for some specific game titles such as Team Fortress 2, the ability to purchase in-game inventory items. In February 2015, Steam began to open similar options for in-game item purchases for third-party games.[59]

Users of Steam's storefront can also purchase games and other software as gifts to be given to another Steam user. Prior to May 2017, users could purchase these gifts to be held in their profile's inventory until they opted to gift them. However, this feature enabled a gray market around some games, where a user in a country where the price of a game was substantially lower than elsewhere could stockpile giftable copies of games to sell to others, particularly in regions with much higher prices.[60] In August 2016, Valve changed its gifting policy to require that games with VAC and Game Ban-enabled games to be gifted immediately to another Steam user, which also served to combat players that worked around VAC and Game Bans,[61] while in May 2017, Valve expanded this policy to all games.[62] The changes also placed limitations on gifts between users of different countries if there is a large difference in pricing for the game between two different regions.[63]

The Steam store also enables users to redeem store product keys to add software from their library. The keys are sold by third-party providers such as Humble Bundle (in which a portion of the sale is given back to the publisher or distributor), distributed as part of a physical release to redeem the game, or given to a user as part of promotions, often used to deliver Kickstarter and other crowd funding rewards. A grey market exists around Steam keys, where less reputable buyers purchase a large number of Steam keys for a game when it is offered for a low cost, and then resell these keys to users or other third-party sites at a higher price, generating profit for themselves.[64][65] This caused some of these third-party sites, like G2A, to be embroiled in this grey market.[66] It is possible for publishers to have Valve to track down where specific keys have been used and cancel them, removing the product from the user's libraries, leaving the user to seek any recourse with the third-party they purchased from.[67] Other legitimate storefronts, like Humble Bundle, have set a minimum price that must be spent to obtain Steam keys as to discourage mass purchases that would enter the grey market.[68]

In 2013, Steam began to accept player reviews of games. Other users can subsequently rate these reviews as helpful, humorous, or otherwise unhelpful, which are then used to highlight the most useful reviews on the game's Steam store page. Steam also aggregates these reviews and enables users to sort products based on this feedback while browsing the store.[69] In May 2016, Steam further broke out these aggregations between all reviews overall and those made more recently in the last 30 days, a change Valve acknowledges to how game updates, particularly those in Early Access, can alter the impression of a game to users.[70] To prevent observed abuse of the review system by developers or other third-party agents, Valve modified the review system in September 2016 to discount review scores for a game from users that activated the product through a product key rather than directly purchased by the Steam Store, though their reviews remain visible.[71] Alongside this, Valve announced that it would end business relations with any developer or publisher that they have found to be abusing the review system.[72]

During mid-2011, Valve began to offer free-to-play games, such as Global Agenda, Spiral Knights and Champions Online; this offer was linked to the company's move to make Team Fortress 2 a free-to-play title.[73] Valve included support via Steamworks for microtransactions for in-game items in these titles through Steam's purchasing channels, in a similar manner to the in-game store for Team Fortress 2. Later that year, Valve added the ability to trade in-game items and "unopened" game gifts between users.[74] Steam Coupons, which was introduced in December 2011, provides single-use coupons that provide a discount to the cost of items. Steam Coupons can be provided to users by developers and publishers; users can trade these coupons between friends in a similar fashion to gifts and in-game items.[75] Steam Market, a feature introduced in beta in December 2012 that would allow users to sell virtual items to others via Steam Wallet funds, further extended the idea. Valve levies a transaction fee of 15% on such sales and game publishers that use Steam Market pay a transaction fee. For example, Team Fortress 2—the first game supported at the beta phase—incurred both fees. Full support for other games was expected to be available in early 2013.[76] In April 2013, Valve added subscription-based game support to Steam; the first game to use this service was Darkfall Unholy Wars.[77]

In October 2012, Steam introduced non-gaming applications, which are sold through the service in the same manner as games.[78] Creativity and productivity applications can access the core functions of the Steamworks API, allowing them to use Steam's simplified installation and updating process, and incorporate features including cloud saving and Steam Workshop.[79] Steam also allows game soundtracks to be purchased to be played via Steam Music or integrated with the user's other media players.[80] Valve have also added the ability for publishers to rent and sell digital movies via the service, with initially most being video game documentaries.[81] Following Warner Bros. Entertainment offering the Mad Max films alongside the September 2015 release of the game based on the series,[82] Lionsgate entered into agreement with Valve to rent over one hundred feature films from its catalog through Steam starting in April 2016, with more films following later.[83] In March 2017, Crunchyroll started offering various anime for purchase or rent through Steam.[84] With the onset of Steam Machines, the Steam storefront also includes the ability to purchase Steam Machine-related hardware.[85]

In conjunction with developers and publishers, Valve frequently provides discounted sales on games on a daily and weekly basis, sometimes oriented around a publisher, genre, or holiday theme, and sometimes allow games to be tried for free during the days of these sales. The site normally offers a large selection of games at discount during its annual Summer and Holiday sales, including gamification of these sales to incentive users to purchase more games.[86]

Privacy and security

The popularity of Steam has led to the service's being attacked by hackers in the past. An attempt occurred in November 2011, when Valve temporarily closed the community forums, citing potential hacking threats to the service. Days later, Valve reported that the hack had compromised one of its customer databases, potentially allowing the perpetrators to access customer information—including encrypted password and credit card details. At that time, Valve was not aware whether the intruders actually accessed this information or discovered the encryption method, but nevertheless warned users to be alert for fraudulent activity.[87][88]

Valve added Steam Guard functionality to the Steam client in March 2011 to protect against the hijacking of accounts via phishing schemes, one of the largest support issues Valve had at the time.[89] Steam Guard was advertised to take advantage of the identity protection provided by Intel's second-generation Core processors and compatible motherboard hardware, which allows users to lock their account to a specific computer. Once locked, activity by that account on other computers must first be approved by the user on the locked computer. Support APIs for Steam Guard are available to third-party developers through Steamworks.[90] Steam Guard also offers two-factor, risk-based authentication that uses a one-time verification code sent to a verified email address associated with the Steam account; this was later expanded to include two-factor authentication through the Steam mobile application, known as Steam Guard Mobile Authenticator.[91] If Steam Guard is enabled, the verification code is sent each time the account is used from an unknown machine.[92]

In 2015, between Steam-based game inventories, trading cards, and other virtual goods attached to a user's account, Valve stated that the potential monetary value had drawn hackers to try to access user accounts for financial benefit, and continue to encourage users to secure accounts with Steam Guard; when trading was introduced in 2011.[93] Valve reported that in December 2015, around 77,000 accounts per month were hijacked, enabling the hijackers to empty out the user's inventory of items through the trading features. To improve security, the company announced that new restrictions would be added in March 2016, under which 15-day holds are placed on traded items unless they activate, and authenticate with Steam Guard Mobile Authenticator.[93][94]

ReVuln, a commercial vulnerability research firm, published a paper in October 2012 that said the Steam browser protocol was posing a security risk by enabling malicious exploits through a simple user click on a maliciously crafted steam:// URL in a browser.[95] The report was taken up by various online publications.[96][97][98][99] This was the second serious vulnerability of gaming-related software following a recent problem with Ubisoft's copy protection system "Uplay";[100] the German IT platform "Heise online" recommended strict separation of gaming and sensitive data, for example using a PC dedicated to gaming, gaming from a second Windows installation, or using a computer account with limited rights dedicated to gaming.[99]

In July 2015, a bug in the software allowed anyone to reset the password to any account by using the "forgot password" function of the client. High-profile professional gamers and streamers lost access to their accounts.[101][102] In December 2015, Steam's content delivery network was misconfigured in response to a DDoS attack, causing cached store pages containing personal information to be temporarily exposed for 34,000 users.[103][104]

In April 2018, Valve added new privacy settings for Steam users, who are able to set if their current activity status is private, visible to friends only, or public; in addition to being able to hide their game lists, inventory, and other profile elements in a similar manner. While these changes brought Steam's privacy settings inline with approaches used by game console services, it also impacted third-party services such as Steam Spy, which relied on the public data to estimate Steam sales count.[105][106]

Valve established a HackerOne bug bounty program in May 2018, a crowdsourced method to test and improve security features of the Steam client.[107]

User interface

Since November 2013, Steam allows for users to review their purchased titles and organize them into categories set by the user and add to favorite lists for quick access.[108] Players can add non-Steam games to their libraries, allowing the game to be easily accessed from the Steam client and providing support where possible for Steam Overlay features. The Steam interface allows for user-defined shortcuts to be added. In this way, third-party modifications and games not purchased through the Steam Store can use Steam features. Valve sponsors and distributes some modifications free-of-charge;[109] and modifications that use Steamworks can also use VAC, Friends, the server browser, and any Steam features supported by their parent game. For most games launched from Steam, the client provides an in-game overlay that can be accessed by a keystroke. From the overlay, the user can access his or her Steam Community lists and participate in chat, manage selected Steam settings, and access a built-in web browser without having to exit the game.[110] Since the beginning of February 2011 as a beta version, the overlay also allows players to take screenshots of the games in process;[111] it automatically stores these and allows the player to review, delete, or share them during or after his or her game session. As a full version on February 24, 2011, this feature was reimplemented so that users could share screenshots on websites of Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit straight from a user's screenshot manager.[112]

Steam's "Big Picture" mode was announced in 2011;[113] public betas started in September 2012 and were integrated into the software in December 2012.[114] Big Picture mode is a 10-foot user interface, which optimizes the Steam display to work on high-definition televisions, allowing the user to control Steam with a gamepad or with a keyboard and mouse. Newell stated that Big Picture mode was a step towards a dedicated Steam entertainment hardware unit.[115] SteamVR, a virtual reality (VR) Big Picture interface, was introduced in beta in January 2014. The SteamVR mode enables the user to operate the Big Picture mode and play any game in their Steam library with a virtual theater displayed through the VR headset, the equivalent of looking at a 225-inch television screen, according to Valve.[116] The mode was first introduced in beta for the Oculus Rift headset[117] and later expanded in March 2015 to support the HTC Vive, a VR unit developed jointly with Valve, with the feature to be publicly released shortly after the Vive's public launch in April 2016.[116][118] In-Home Streaming was introduced in May 2014; this allows users to stream games installed on one computer to another—regardless of platform—on the same home network.[119]

The Steam client, as part of a social network service, allows users to identify friends and join groups using the Steam Community feature.[120] Users can use text chat and peer-to-peer VoIP with other users, identify which games their friends and other group members are playing, and join and invite friends to Steamworks-based multiplayer games that support this feature. Users can participate in forums hosted by Valve to discuss Steam games. Each user has a unique page that shows his or her groups and friends, game library including earned achievements, game wishlists, and other social features; users can choose to keep this information private.[121] In January 2010, Valve reported that 10 million of the 25 million active Steam accounts had signed up to Steam Community.[122] In conjunction with the 2012 Steam Summer Sale, user profiles were updated with Badges reflecting the user's participation in the Steam community and past events.[123] Steam Trading Cards, a system where players earn virtual trading cards based on games they own, were introduced May 2013. Using them, players can trade with other Steam users on the Steam Marketplace and use them to craft "Badges", which grant rewards such as game discount coupons, emoticons, and the ability to customize their user profile page.[124][125] In 2010, the Steam client became an OpenID provider, allowing third-party websites to use a Steam user's identity without requiring the user to expose his or her Steam credentials.[126][127] In order to prevent abuse, access to most community features is restricted until a one-time payment of at least US$5 is made to Valve. This requirement can be fulfilled by making any purchase of five dollars or more on Steam, or by adding at the same amount to their wallet.[128]

Through Steamworks, Steam provides a means of server browsing for multiplayer games that use the Steam Community features, allowing users to create lobbies with friends or members of common groups. Steamworks also provides Valve Anti-Cheat (VAC), Valve's proprietary anti-cheat system; game servers automatically detect and report users who are using cheats in online, multiplayer games.[129] In August 2012, Valve added new features—including dedicated hub pages for games that highlight the best user-created content, top forum posts, and screenshots—to the Community area.[130] In December 2012, a feature where users can upload walkthroughs and guides detailing game strategy was added.[131] Starting in January 2015, the Steam client allowed players to livestream to Steam friends or the public while playing games on the platform.[132][133] For the main event of The International 2018 Dota 2 tournament, Valve launched Steam.tv as an major update to Steam Broadcasting, adding Steam chat and Steamworks integration for spectating matches played at the event.[134] Valve plans for other games to be supported on the service in the future.[135]

In September 2014, Steam Music was added to the Steam client, allowing users to play through music stored on their computer or to stream from a locally networked computer directly in Steam.[136][137] An update to the friends and chat system was released in July 2018, allowing for non-peer-to-peer chats integrated with voice chat and other features that were compared to Discord.[138][139]

Developer features

Valve offers Steamworks, an application programming interface (API) that provides development and publishing tools to take advantage of Steam client's features, free-of-charge to game and software developers.[140] Steamworks provides networking and player authentication tools for both server and peer-to-peer multiplayer games, matchmaking services, support for Steam community friends and groups, Steam statistics and achievements, integrated voice communications, and Steam Cloud support, allowing games to integrate with the Steam client. The API also provides anti-cheating devices and digital copy management.[141] Developers of software available on Steam are able to track sales of their titles through the Steam store. In February 2014, Valve announced that it would begin to allow developers to set up their own sales for their games independent of any sales that Valve may set.[142] Valve added the ability for developers to sell games under an early access model with a special "Early Access" section of the Steam store, starting in March 2013. This program allows developers to release functional but yet-incomplete products such as beta versions to the service to allow users to buy the titles and help provide testing and feedback towards the final production. Early access also helps to provide funding to the developers to help complete their titles.[143] The Early Access approach allowed more developers to publish games onto the Steam service without the need for Valve's direct curation of titles, significantly increasing the number of available titles on the service.[144]

Developers are able to request Steam keys of their products to use as they see fit, such as to give away in promotions, to provide to selected users for review, or to give to key resellers for different profitization. Valve generally honors all such requests, but clarified that they would evaluate some requests to avoid giving keys to games or other offerings that are designed to manipulate the Steam storefront and other features. For example, Valve said that a request for 500,000 keys for a game that has significantly negative reviews and 1,000 sales on Steam is unlikely to be granted.[145]

Steam Workshop

The Steam Workshop is a Steam account-based hosting service for videogame user-created content. Depending on the title, new levels, art assets, gameplay modifications, or other content may be published to or installed from the Steam Workshop through an automated, online account-based process. The Workshop was originally used for distribution of new items for Team Fortress 2;[146] it was redesigned to extend support for any game in early 2012, including modifications for The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim.[147] A May 2012 patch for Portal 2, enabled by a new map-making tool through the Steam Workshop, introduced the ability to share user-created levels.[148] Independently-developed games, including Dungeons of Dredmor, are able to provide Steam Workshop support for user-generated content.[149] Dota 2 became Valve's third published title available for the Steam Workshop in June 2012; its features include customizable accessories, character skins, and announcer packs.[150]

As of January 2015, Valve themselves had provided some user-developed Workshop content as paid-for features in Valve-developed games, including Team Fortress 2 and Dota 2; with over $57 million being paid to content creators using the Workshop.[151][152] Valve began allowing developers to use these advanced features in January 2015; both the developer and content generator share the profits of the sale of these items; the feature went live in April 2015, starting with various mods for Skyrim.[151][153][154] This feature was pulled a few days afterward following negative user feedback and reports of pricing and copyright misuse.[155][156][157] Six months later, Valve stated they were still interested in offering this type of functionality in the future, but would review the implementation to avoid these previous mistakes.[158] In November 2015, the Steam client was updated with the ability for game developers to offer in-game items for direct sale via the store interface, with Rust being the first game to use the feature.[159][160][161]

Steam for Schools

Steam for Schools is a function-limited version of the Steam client that is available free-of-charge for use in schools. It is part of Valve's initiative to support gamification of learning for classroom instruction; it was released alongside free versions of Portal 2 and a standalone program called "Puzzle Maker" that allows teachers and students to create and manipulate levels. It features additional authentication security that allows teachers to share and distribute content via a Steam Workshop-type interface, but blocks access from students.[162][163]

Storefront curation

In general, up through 2012, Valve would manually select games to be included on the Steam service, limiting these to games that either had a major developer supporting them, or smaller studios with proven track records for Valve's purposes. Valve have sought ways to enable more games to be offered through Steam, while pulling away from manually approving games for the service, short of validating that a game runs on the platforms the publisher had indicated.[164] Alden Kroll, a member of the Steam development team, said that Valve knows Steam is in a near-monopoly for game sales on personal computers, and the company does not want to be in a position to determine what gets sold, and thus had tried to find ways to make the process of adding games to Steam outside of their control.[164] At the same time, Valve recognized that unfettered control of games onto the service can lead to discovery problems as well as low-quality games that are put onto the service for a cash grab.[164]

Steam Greenlight

Valve's first attempt to streamline game addition to the service was with Steam Greenlight, announced in July 2012 and released the following month.[165] Through Greenlight, Steam users would choose which games were added to the service. Developers were able to submit information about their games, as well as early builds or beta versions, for consideration by users. Users would pledge support for these games, and Valve would help to make top-pledged games available on the Steam service.[166] In response to complaints during its first week that finding games to support was made difficult by a flood of inappropriate or false submissions,[167] Valve required developers to pay US$100 to list a game on the service to reduce illegitimate submissions. Those fees were donated to the charity Child's Play.[168] This fee was met with some concern from smaller developers, who often are already working in a deficit and may not have the money to cover such fees.[169] A later modification allowed developers to put conceptual ideas on the Greenlight service to garner interest in potential projects free-of-charge; votes from such projects are only visible to the developer.[170] Valve also allowed non-gaming software to be voted onto the service through Greenlight.[171]

The initial process offered by Steam Greenlight was panned because while developers favored the concept, the rate of games that are eventually approved by Valve is very small.[172] At the time, Valve acknowledged that this was a problem and believed it could be improved upon it.[173] In January 2013, Newell stated that Valve recognized that its role in Greenlight was perceived as a bottleneck, something the company was planning to eliminate in the future through an open marketplace infrastructure.[174][175] On the eve of Greenlight's first anniversary, Valve simultaneously approved 100 titles through the Greenlight process to demonstrate this change of direction.[176] While the Greenlight service had helped to bring more and varied games onto Steam without excessive bureaucracy, it also led to an excessively large number of games on the service that make it difficult for a single title to stand out, and as early as 2014, Valve had discussed plans to phase out the Greenlight process in favor of providing developers with easier means to put their games onto the Steam service.[177]

Steam Direct

Steam Greenlight was phased out and replaced with Steam Direct in June 2017.[178] With Steam Direct, a developer or publisher wishing to distribute their game on Steam needs only to complete appropriate identification and tax forms for Valve and then pay a recoupable application fee for each game they intend to publish. Once they apply, a developer must wait thirty days before publishing the game as to give Valve the ability to review the game to make sure it is "configured correctly, matches the description provided on the store page, and doesn't contain malicious content."[178]

On announcing its plans for Steam Direct, Valve suggested the fee would be in the range of $100–5,000, meant to encourage earnest software submissions to the service and weed out poor quality titles that are treated as shovelware, improving the discovery pipeline to Steam's customers.[179] Smaller developers raised concerns about the Direct fee harming them, and excluding potentially good indie games from reaching the Steam marketplace.[169] Valve opted to set the Direct fee at $100 after reviewing concerns from the community, recognizing the need to keep this at a low amount for small developers, and outlining plans to improve their discovery algorithms and inject more human involvement to help these.[180] Valve then refunds the fee should the game exceed $1,000 in sales.[181] In the process of transitioning from Greenlight to Direct, Valve mass-approved most of the 3,400 remaining titles that were still in Greenlight, though the company noted that not all of these were at a state to be published. Valve anticipated that the volume of new games added to the service would further increase with Direct in place.[182] Some groups, such as publisher Raw Fury and crowd funding/investment site Fig, have offered to pay the Direct fee for indie developers who can not afford it.[183][184]

Discovery updates

Without more direct interaction on the curation process, allowing hundreds more games on the service, Valve had looked to find methods to allow players to find games they would be more likely to buy based on previous purchase patterns.[164] The September 2014 "Discovery Update" added tools that would allow existing Steam users to be curators for game recommendations, and sorting functions that presented more popular titles and recommended titles specific to the user, as to allow more games to be introduced on Steam without the need of Steam Greenlight, while providing some means to highlight user-recommended games.[185] This Discovery update was considered successful by Valve, as they reported in March 2015 in seeing increased use of the Steam Storefront and an increase in 18% of sales by revenue from just prior to the update.[186] A second Discovery update was released November 2016, giving users more control over what titles they want to see or ignore within the Steam Store, alongside tools for developers and publishers to better customize and present their game within these new users preferences.[187][188] By February 2017, Valve reported that with the second Discovery update, the number of games shown to users via the store's front page increased by 42%, with more conversions into sales from that viewership. In 2016, more games are meeting a rough metric of success defined by Valve as selling more than $200,000 in revenues in its first 90 days of release.[189] Valve added a "Curator Connect" program in December 2017. Curators can set up descriptors for the type of games they are interested in, preferred languages, and other tags along with social media profiles, while developers can find and reach out to specific curators from this information, and, after review, provide them directly with access to their game. This step, which eliminates the use of a Steam redemption key, is aimed to reduce the reselling of keys, as well as dissuade users that may be trying to game the curator system to obtain free game keys.[190]

Valve has attempted to deal with "fake games", those that are built around reused assets and little other innovation, designed to misuse Steam's features for the benefit only to the developer or select few users. To help assist finding and removing these games from the service, the company added Steam Explorers atop its existing Steam Curator program, according to various YouTube personalities that have spoken out about such games in the past and with Valve directly, including Jim Sterling and TotalBiscuit. Any Steam user is able to sign up to be an Explorer, and are asked to look at under-performing games on the service as to either vouch that the game is truly original and simply lost among other releases, or if it is an example of a "fake game", at which point Valve can take action to remove the game.[191][192]

Policies

In June 2015, Valve created a formal process to allow purchasers to request full refunds on games they had purchased on Steam for any reason, with refunds guaranteed within the first two weeks as long as the player had not spent more than two hours in the game.[193] Prior to June 2015, Valve had a no-refunds policy, but allowed them in certain circumstances, such as if third-party content had failed to work or improperly reports on certain features. For example, the Steam version of From Dust was originally stated to have a single, post-installation online DRM check with its publisher Ubisoft, but the released version of the game required a DRM check with Ubisoft's servers each time it was used. At the request of Ubisoft, Valve offered refunds to customers who bought the game while Ubisoft worked to release a patch that would remove the DRM check altogether.[194] On The War Z's release, players found that the game was still in an alpha-build state and lacked many of the features advertised on its Steam store page. Though the developers Hammerpoint Interactive altered the description after launch to reflect the current state of the game software, Valve removed the title from Steam and offered refunds to those who had bought it.[195] Valve also removed Earth: Year 2066 from the Early Access program and offered refunds after discovering that the game's developers had reused assets from other games and used developer tools to erase negative complaints about the title.[196] Valve stated it would continue to work on improving the discovery process for users, taking principles they learned in providing transparency for matchmaking in Dota 2 to make the process better, and using that towards Steam storefront procedures to help refine their algorithms with user feedback.[197]

Valve has full authority to remove games from the service for various reasons; however games that are removed can still be downloaded and played by those that have already purchased these titles.[198] Another reason would be games that have had their licenses expired may no longer be sold, such as when a number of Transformers games published by Activision under license from Hasbro were removed from the store in January 2018.[199] Grand Theft Auto: Vice City was removed from Steam in 2012 because of a claim from the Recording Industry Association of America over an expired license for one of the songs on the soundtrack.[198] Around the launch of Electronic Arts' (EA) own digital storefront Origin during the same year, Valve removed Crysis 2, Dragon Age II, and Alice: Madness Returns from Steam because the terms of service prevented games from having their own in-game storefront for downloadable content.[200] In the case of Crysis 2, a "Maximum Edition" that contained all the available downloadable content for the game and removed the in-game storefront was re-added to Steam.[201] Valve also remove games that are formally stated to be violating copyright or other intellectual property when given such complaints. In 2016, Valve removed Orion by Trek Industries when Activision filed a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) complaint about the game after it was discovered that one of the game's artists had taken, among other assets, gun models directly from Call of Duty: Black Ops 3 and Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare.[202][203]

Trolling and other violations

With the launch of Steam Direct, effectively removing any curation of games by Valve prior to being published on Steam, there have been several incidents of published games that have attempt to mislead Steam users. Starting in June 2018, Valve has taken actions against games and developers that are "trolling" the system; in September 2018, Valve explicitly defined that trollers on Steam "aren't actually interested in good faith efforts to make and sell games to you or anyone" and instead use "game shaped object" that could be considered a video game but would not be considered a "good" video game by a near-unanimity of users.[204][205] As an example, Valve's Lombardi stated that the game Active Shooter, which would have allowed the player to play as either a SWAT team member tasked to take down the shooter at a school shooting incident or as the shooter themselves, was an example of trolling, as he described it was "designed to do nothing but generate outrage and cause conflict through its existence".[206] While Active Shooter had been removed from Steam prior to Valve issuing this policy statement under the reasoning that the development had abused the Steam service's terms and conditions, Lombardi asserted that they would have removed the game if it had been offered by any other developer.[206] A day after making this new policy, Valve subsequently removed four yet-released titles from the service that appeared to also be created to purposely create outrage, including AIDS Simulator and ISIS Simulator.[207] Within a month of clarifying its definition of trolling, Valve removed approximately 170 games from Steam.[208]

In addition to removing bad actors from the service, Valve has also taken steps to reduce the impact of "fake games" and their misuse on the service. In May 2017, Valve identified that there were several games on the service with trading card support, where the developer distributed game codes to thousands of bot-operated accounts that would run the game to earn trading cards that they could then sell for profit; these games would also create false positives that make these titles appear more popular than they really were and would impact games suggested to legitimate players through their store algorithms, affecting Steam's Discovery algorithms. Subsequent to this patch, games must reach some type of confidence factor based on actual playtime before they can generate trading cards, with players credited for their time played towards receiving trading cards before this metric is met.[209][210] Valve identified a similar situation in June 2018 with "fake games" that offered large numbers of game achievements without little gameplay aspects, which some users would use to artificially raise their global achievement statistics displayed on their profile. Valve plans to use the same approach and algorithms to identify these types of games, limiting these games to only one thousand total achievements and discounting these achievements towards a user's statistics.[211]

Other actions taken by developers against the terms of service or other policies will prompt Valve to remove games.[212] Some noted examples include:

- Following a lawsuit that the developer Digital Homicide Studios had issued against 100 unnamed Steam users for leaving poor reviews of its games around September 2016, Valve subsequently removed their games from the storefront "for being hostile to Steam customers", according to a response written by Valve's Doug Lombardi.[213] Digital Homicide later dropped the lawsuit, in part due to the removal of the games from Steam affecting their financial ability to proceed with the lawsuit.[214]

- In September 2017, Valve removed 170 games developed by Silicon Echo (operating under several different names) that they had released over a period of a few months in 2017, after the implementation of Steam Direct. Valve cited that these were cheap "fake games" that relied on "asset flipping" with pre-existing Unity assets so that they could be published quickly, and were designed to take advantage of the trading card market to allow players and the developers to profit from the trading card sales.[215]

- In February 2018, after discovering that the CEO of Insel Games had requested the company's employees to write positive Steam reviews for its games as to manipulate the review scores, Valve removed all of Insel's titles from the service and banned the company from it.[216]

- In July 2018, updates to the game Abstractism added executables that were found to be cryptocurrency dataminers, as well as offering Steam inventory items that used assets from other Valve games, which mislead users looking for these for trading. Valve removed the game from Steam when these changes were reported by players shortly after.[217] A similar situation was found for the game Climber, which offered trading cards that used Valve's games assets as to be used by scammers. Valve had removed the games, and built in additional trade protections, warning users of trades involving recently released games or for cards for games they do not own to prevent such scamming.[218]

Mature content

Valve has also removed or threatened to remove games due to inappropriate or mature content, though there was often confusion as to what material qualified for this, such as a number of mature, but non-pornographic visual novels being threatened. For example, Eek Games' House Party included scenes of nudity and sexual encounters in its original release, which drew criticism from the National Center on Sexual Exploitation, leading Valve to remove the title from the service. Eek Games were later able to satisfy Valve's standards by including censor bars within the game and allowing the game to be readded to Steam, though offered a patch on their website to remove the bars.[219] In May 2018, several developers of anime-stylized games that contained some light nudity, such as HuniePop, had been told by Valve they had to address the issues of sexual content within their games or face removal from Steam, leading to questions of inconsistent application of Valve's policies. The National Center on Sexual Exploitation took credit for convincing Valve to target these titles. However, Valve later redacted its orders, allowing these games to remain though told the developers Valve would re-evaluate the games and inform them of any content that would need to be changed or removed.[220]

In June 2018, Valve clarified its policy on content, taking a more hands-off approach rather than deem what content is inappropriate, outside of illegal material. Rather than trying to make decisions themselves on what content is appropriate, Valve stated they were improving Discovery tools so that users have better ability to block games that they do not want to see, as well as develop anti-harassment tools to support developers who may find their game amid controversy;[204] The tools were released in September 2018; the tools consist of methods for developers and publishers to indicate the type of mature content (including violence, nudity, and sexual content), and allow them to provide a short description of what specifically runs afoul of that. Users can block games that are marked with this type of content from appearing in the store, and if they have not blocked it, they are presented with the description given by the developer or publisher before they can continue to the store page. Developers and publishers with existing games on Steam have been strongly encouraged to complete these forms for these games, while Valve will use moderators to make sure new games are appropriately marked.[205] Until these tools were in place, some adult-themed games were delayed for release.[221][222][223] Negligee: Love Stories developed by Dharker Studios was one of the first sexually-explicit games to be offered after the introduction of the tools in September 2018. Dharker noted that in discussions with Valve that they would be liable for any content-related fines or penalties that countries may place on Valve, a clause of their publishing contract for Steam, and took steps to restrict sale of the game in over 20 regions.[224]

Platforms

Microsoft Windows

Steam originally released exclusively for Microsoft Windows in 2003, but has since been ported to other platforms.[225]

Newer Steam client versions use features provided by a Google Chrome engine. To take advantage of some of Chrome's features for newer interface elements, Steam needs to use 64-bit versions of Chrome, which, since around 2016, are unsupported on Windows XP and Windows Vista. Steam on Windows also relies on some security features built into later versions of Windows. Valve announced that it will be dropping Steam support for XP and Vista at the start of 2019, and while they will still be able to use the Steam client, may not have access to new features to be added. At the time of this announcement in June 2018, only about 0.22% of the Steam users would be affected by this.[226]

macOS

On March 8, 2010, Valve announced a client for Mac OS X.[225] The announcement was preceded by a change in the Steam beta client to support the cross-platform WebKit web browser rendering engine instead of the Trident engine of Internet Explorer.[227][228][229] Before this announcement, Valve teased the release by e-mailing several images to Mac community and gaming websites; the images featured characters from Valve games with Apple logos and parodies of vintage Macintosh advertisements.[230][231] Valve developed a full video homage to Apple's 1984 Macintosh commercial to announce the availability of Half-Life 2 and its episodes on the service; some concept images for the video had previously been used to tease the Mac Steam client.[232]

Steam for Mac OS X was originally planned for release in April 2010; but was pushed back to May 12, 2010, following a beta period. In addition to the Steam client, several features were made available to developers, allowing them to take advantage of the cross-platform Source engine, and platform and network capabilities using Steamworks.[233] Through SteamPlay, the macOS client allows players who have purchased compatible products in the Windows version to download the Mac versions at no cost, allowing them to continue playing the game on the other platform. Some third-party titles may require the user to re-purchase them to gain access to the cross-platform functionality.[234] The Steam Cloud, along with many multiplayer PC games, also support cross-platform play, allowing Windows, macOS, and Linux players to play with each other regardless of their respective platforms.[225]

Linux

Valve announced in July 2012 that it was developing a Steam client for Linux and modifying the Source engine to work natively on Linux, based on the Ubuntu distribution.[235] This announcement followed months of speculation, primarily from the website Phoronix that had discovered evidence of Linux developing in recent builds of Steam and other Valve software.[236] Newell stated that getting Steam and games to work on Linux is a key strategy for Valve; Newell called the closed nature of Microsoft Windows 8, "a catastrophe for everyone in the PC space", and that Linux would maintain "the openness of the platform".[237] Valve is extending support to any developers that want to bring their games to Linux, by "making it as easy as possible for anybody who's engaged with us—putting their games on Steam and getting those running on Linux", according to Newell.[237]

The team developing the Linux client had been working for a year before the announcement to validate that such a port would be possible.[238] As of the official announcement, a near-feature-complete Steam client for Linux had been developed and successfully run on Ubuntu.[238] Internal beta testing of the Linux client started in October 2012; external beta testing occurred in early November the same year.[239][240] Open beta clients for Linux were made available in late December 2012,[241] and the client was officially released in mid-February 2013.[242] At the time of announcement, Valve's Linux division assured that its first game on the OS, Left 4 Dead 2, would run at an acceptable frame rate and with a degree of connectivity with the Windows and Mac OS X versions. From there, it began working on porting other games to Ubuntu and expanding to other Linux distributions.[235][243][244] Linux games are also eligible for SteamPlay availability.[245] Versions of Steam working under Fedora and Red Hat Enterprise Linux were released by October 2013.[246] By June 2014, the number of Linux-compatible games on Steam had reached over 500,[247] surpassing over 1,000 by March 2015.[248] A year later, this number doubled to over 2,000.[249]

In August 2018, Valve released a beta version of Proton, an open-source Windows compatibility layer for Linux, so that Linux users of the Steam client would be able to run Windows games directly through Steam for Linux, suppressing the need to install the Steam client in Wine. Proton is composed of a set of open-source tools including Wine and DXVK among others and the software allows the use of Steam supported controllers, even those not compatible with Windows.[250]

Consoles

At E3 2010, Newell announced that Steamworks would arrive on the PlayStation 3 with Portal 2. It would provide automatic updates, community support, downloadable content and other unannounced features.[251] Steamworks made its debut on consoles with Portal 2's PlayStation 3 release. Several features—including cross-platform play and instant messaging, Steam Cloud for saved games, and the ability for PS3 owners to download Portal 2 from Steam (Windows and Mac) at no extra cost—were offered.[252] Valve's Counter-Strike: Global Offensive also supports Steamworks and cross-platform features on the PlayStation 3, including using keyboard and mouse controls as an alternative to the gamepad.[253] Valve said it "hope[s] to expand upon this foundation with more Steam features and functionality in DLC and future content releases".[254] In October 2016, Valve announced plans to provide controller customization features similar to what Steam offers for the Steam controller for other third-party controllers, starting with the DualShock 4.[255]

The Xbox 360 does not have support for Steamworks. Newell said that they would have liked to bring the service to the console through the game Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, which would have allowed Valve to provide the same feature set that it did for the PlayStation 3,[256] but later said that cross-platform play would not be present in the final version of the game.[257] Valve attributes the inability to use Steamworks on the Xbox 360 to limitations in the Xbox Live regulations of the ability to deliver patches and new content. Valve's Erik Johnson stated that Microsoft required new content on the console to be certified and validated before distribution, which would limit the usefulness of Steamworks' delivery approach.[258]

Mobile platforms

Valve released an official Steam client for iOS and Android devices in late January 2012, following a short beta period.[259] The application allows players to log into their accounts to browse the storefront, manage their games, and communicate with friends in the Steam community. The application also incorporates a two-factor authentication system that works with Steam Guard, further enhancing the security of a user's account. Newell stated that the application was a strong request from Steam users and sees it as a means "to make [Steam] richer and more accessible for everyone".[260] A mobile Steam client for Windows Phone devices was released in June 2016.[261]

On May 14, 2018, a software-only version of the Steam Link technology was released in beta to allow users to stream games to Android phones.[262] It was also submitted by Valve to the iOS App Store, but was denied by Apple Inc., who cited "business conflicts with app guidelines".[262][263] Apple later clarified its rule at the following Apple Worldwide Developers Conference in early June, in that iOS apps may not offer an app-like purchasing store, but does not restrict apps that provide remote desktop support that would allow users to purchases content through the remote desktop.[264] In response, Valve removed the ability to purchase games or other content through the Steam Link App and resubmitted it for approval in June 2018.[265]

Valve also plans to release a Steam Video app for mobile platforms later that year to allow users to stream any media they own through Steam.[266]

Steam Machine

Prior to 2013, industry analysts believed that Valve was developing hardware and tuning features of Steam with apparent use on its own hardware. These computers were pre-emptively dubbed as "Steam Boxes" by the gaming community and expected to be a dedicated machine focused upon Steam functionality and maintaining the core functionality of a traditional video game console.[267] In September 2013, Valve unveiled SteamOS, a custom Linux-based operating system they had developed specifically aimed for running Steam and games, a console input device called the Steam Controller, and the final concept of the Steam Machine hardware.[268] Unlike other consoles, the Steam Machine does not have set hardware; its technology is implemented at the discretion of the manufacturer and is fully customizable, much like a personal computer.[269]

Market share and impact

Users

Valve reported that there were 125 million active accounts on Steam by the end of 2015.[lower-alpha 1] By August 2017, the company reported that there were 27 million new active accounts since January 2016, bringing the total number of active users to at least 150 million.[271] While most accounts are from North America and Western Europe, Valve has seen a significant growth in accounts from Asian countries within recent years, spurred by their work to help localize the client and make additional currency options available to purchasers.[271] As of November 2017, more than half of the Steam userbase is fluent in Chinese, an effect created by the explosive growth of PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds during 2017.[272] Following a Chinese government-ordered block of many of Steam's functions in December 2017,[273] Valve and Perfect World announced they would help to provide an officially-sanctioned version of Steam that will meet Chinese Internet requirements.[274]

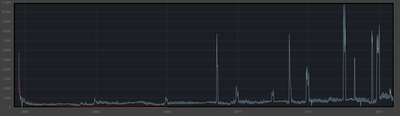

Valve also considers the concurrent user count a key indicator of the success of the platform, reflecting how many accounts were logged into Steam at the same time. By August 2017, Valve reported that they saw an peak of 14 million concurrent players, up from 8.4 million in 2015, with 33 million concurrent players each day and 67 million each month.[271] By January 2018, the peak online count had reached 18.5 million, with over seven million playing a game.[275]

Sales and distribution

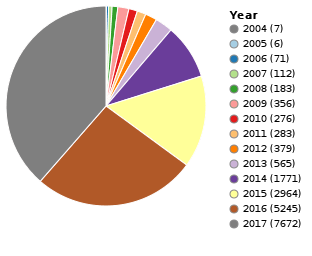

Steam has grown significantly since its launch in 2003. Whereas the service started with seven games in 2004, it was selling over 18,000 games by the end of 2017, with over 7,600 added to the service in that year alone.[144][278] The growth of games on Steam is attributed to changes in Valve's curation approach, which allows publishers to add games without having Valve's direct involvement enabled by the Greenlight and Early Access models, and games supporting virtual reality technology.[144]

Though Steam provides direct sales data to a game's developer and publisher, it does not provide any public sales data or provide such data to third-party sales groups like NPD Group. In 2011, Valve's Jason Holtman stated that the company felt that such sales data was outdated for a digital market, since such data, used in aggregate from other sources, could lead to inaccurate conclusions.[279][280] Data that Valve does provide cannot be released without permission because of a non-disclosure agreement with Valve.[281][282]

Developers and publishers have expressed the need to have some metrics of sales for games on Steam, as this allows them to judge the potential success of a title by reviewing how similar games had performed. This led to the creation of algorithms that worked on publicly-available data through user profiles to estimate sales data with some accuracy, which led to the creation of the website Steam Spy in 2015.[283] Steam Spy was credited with being reasonably accurate, but in April 2018, Valve added its new privacy settings that defaulted to hiding user game profiles by default, stating this was part of compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation in the European Union. The change broke the method Steam Spy had collected data, rendering it unusable.[284] A few months later, another method had been developed using game achievements to estimate sales with similar accuracy, but Valve shortly changed the Steam API that reduced the functionality of this service. Some have asserted that Valve used the General Data Protection Regulation change as a means to block methods of estimating sales data,[285] though Valve has since promised to provide tools to developers to help gain such insights that they say will be more accurate than Steam Spy was.[286]

Because of Valve's oversight of sales data, estimates of how much of a market share Steam has in the video game market is difficult to compile. However, Stardock, the previous owner of competing platform Impulse, estimated that as of 2009, Steam had a 70% share of the digital distribution market for video games.[287] In early 2011, Forbes reported that Steam sales constituted 50–70% of the US$4 billion market for downloaded PC games and that Steam offered game producers gross margins of 70% of purchase price, compared with 30% at retail.[288] Steam's success has led to some criticism because of its support of DRM and for being an effective monopoly.[289][290] Free Software Foundation founder Richard Stallman commented on the issue following the announcement that Steam would come to Linux; he said that while he supposes that its release can boost GNU/Linux adoption leaving users better off than with Microsoft Windows, he stressed that he sees nothing wrong with commercial software but that the problem is that Steam is unethical for not being free software and that its inclusion in GNU/Linux distributions teaches the users that the point is not freedom and thus works against the software freedom that is his goal.[291]

In November 2011, CD Projekt, the developer of The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings revealed that Steam was responsible for 200,000 (80%) of the 250,000 online sales of the game.[292] Steam was responsible for 58.6% of gross revenue for Defender's Quest during its first three months of release across six digital distribution platforms—comprising four major digital game distributors and two methods of purchasing and downloading the game directly from the developer.[293] In September 2014, 1.4 million accounts belonged to Australian users; this grew to 2.2 million by October 2015.[294]

Steam's customer service has been highly criticized, with users citing poor response times or lack of response in regards to issues such as being locked out of one's library or having a non-working game redemption key. In March 2015, Valve had been given a failing "F" grade from the Better Business Bureau due to a large number of complaints in Valve's handling of Steam, leading Valve's Erik Johnson to state that "we don't feel like our customer service support is where it needs to be right now".[295] Johnson stated the company plans to better integrate customer support features into the Steam client and be more responsive to such issues.[295] In May 2017, in addition to hiring more staff for customer service, Valve publicized pages that show the number and type of customer service requests it was handling over the last 90 days, with an average of 75,000 entered each day. Of those, requests for refunds were the largest segment, and which Valve could resolve within hours, followed by account security and recovery requests. Valve stated at this time that 98% of all service requests were processed within 24 hours of filing.[296]

Curation

The addition of Greenlight and Direct have accelerated the number of titles present on the service, with almost 40% of the 19,000 games on Steam by the end of 2017 having been released in 2017.[297] Prior to Greenlight, Valve saw about five new titles published each week. Greenlight expanded this to about 70 per week, and which doubled to 180 per week following the introduction of Direct.[298] As these processes allow developers to publish games on Steam with minimal oversight from Valve, journalists have criticized Valve for lacking curation policies that make it difficult to find quality games among poorly-produced titles, aka "shovelware".[299][300]

Following the launch of Steam Direct, allowing games to be published without Valve's curation, members of the video game industry were split on Valve's hands-off approach. Some praised Valve in favoring to avoid trying to be a moral adjudicator of content and letting consumers decide what content they want to see, while others felt that this would encourage some developers to publish games on Steam that are purposely hateful or degenerate of some social classes, like LGBTQ, and that Valve's reliance on user filters and algorithms may not succeed in blocking undesirable content from certain users. Some further criticized the decision based on the financial gain, as Valve collects 30% of all sales through Steam, giving the company reason to avoid blocking any game content, and further compounds the existing curation problems the service has.[301][302][303][304] The National Center on Sexual Exploitation issued a statement that "denounces this decision in light of the rise of sexual violence and exploitation games being hosted on Steam", and that "In our current #MeToo culture, Steam made a cowardly choice to shirk its corporate and social responsibility to remove sexually violent and exploitive video games from its platform".[305]

Sector competition

From its release in 2003 through to nearly 2009, Steam had a mostly uncontested hold over the PC digital distribution market before major competitors emerged with the largest competitors in the past being services like Games for Windows – Live and Impulse, both of which were shut down in 2013 and 2014, respectively.[306][307] Sales via the Steam catalog are estimated to be between 50 and 75 percent of the total PC gaming market.[287][4] Steam’s critics often refer to the service as a monopoly, and claim that placing such a percentage of the overall market can be detrimental to the industry as a whole and that sector competition can only yield positive results for the consumer.[308][309] Several developers also noted that Steam's influence on the PC gaming market is powerful and one that smaller developers cannot afford to ignore or work with, but believe that Valve's corporate practices for the service make it a type of "benevolent dictator", as Valve attempts to make the service as amenable to developers.[310]

As Steam has grown in popularity, many other competing services have been surfacing trying to emulate their success. The most notable major competitors are Electronic Arts' (EA) Origin service, Ubisoft's Uplay, Blizzard Entertainment's Battle.net, and CD Projekt's GOG.com. Battle.net competes as a publisher exclusive platform, while GOG.com's catalog includes many of the same titles as Steam but offers them in a DRM-free platform. Upon launch of EA's Origin in 2011, several EA-published titles were no longer available for sale, and users feared that future EA titles would be limited to Origin's service. Newell expressed an interest in EA games returning to the Steam catalog though noted the situation was complicated. Newell stated "We have to show EA it’s a smart decision to have EA games on Steam, and we’re going to try to show them that."[311] Ubisoft still publishes their games on the Steam platform, however most games published since the launch of Uplay require this service to run after launching the game from Steam.[312]

Legal issues

Steam's predominance in the gaming market has led to Valve becoming involved in various legal cases involving it. The lack of a formal refund policy led the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) to sue Valve in September 2014 for violating Australian consumer laws that required stores to offer refunds for faulty or broken products.[313] The Commission won the lawsuit in March 2016, though recognizing Valve changed its policy in the interim.[314] The ACCC argued to the court that Valve should be fined 3 million Australian dollars "in order to achieve both specific and general deterrents, and also because of the serious nature of the conduct" prior to their policy changes. Valve argued that from the previous court case that "no finding that Valve's conduct was intended to mislead or deceive consumers", and argued for only a A$250,000 fine.[315] In December 2016, the court ruled with the ACCC and fined Valve A$3 million, as well as requiring Valve to include proper language for Australian consumers outlining their rights when purchasing games off Steam.[316] Valve sought to appeal the rulings, arguing in part that they did not have a physical presence in Australia, but these were thrown out by higher courts by December 2017.[317] In January 2018, Valve filed for a "special leave" of the court's decision, appealing to the High Court of Australia,[318] but the High Court dismissed this request, affirming that Valve was still bound by Australian law since it sold products directly to Australian citizens.[319] Later in September 2018, Valve's Steam refund policy was found to be in violation of France's consumer laws, and were fined €147,000 along with requiring Valve to modify their refund policy appropriately.[320]

In December 2015, the French consumer group UFC Que Choisir initiated a lawsuit against Valve for several of their Steam policies that conflict or run afoul of French law, including the restriction against reselling of purchased games, which is legal in the European Union.[321] In August 2016, BT Group filed a lawsuit against Valve stating that Steam's client infringes on four of their patents, which they state are used within the Steam Library, Chat, Messaging, and Broadcasting.[322]

In 2017, the European Commission began investigating Valve and five other publishers—Bandai Namco Entertainment, Capcom, Focus Home Interactive, Koch Media and ZeniMax Media—for anti-competitive practices, specifically the use of geo-blocking through the Steam storefront and Steam product keys to prevent access to software to citizens of certain countries. Such practices would be against the Digital Single Market initiative set by the European Union.[323] The French gaming trade group, Syndicat National du Jeu Vidéo, noted that geo-blocking was a necessary feature to hinder inappropriate product key reselling, where a group buys a number of keys in regions where the cost is low, and then resells them into regions of much higher value to profit on the difference, outside of European oversight and tax laws.[324]

Notes

References

- ↑ "Steam Translation Server – Welcome". Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ "steampowered.com Site Overview". Alexa Internet. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ↑ "steamcommunity.com Site Overview". Alexa Internet. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- 1 2 Edwards, Cliff (November 4, 2013). "Valve Lines Up Console Partners in Challenge to Microsoft, Sony". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2013.