Colin Firth

| Colin Firth CBE | |

|---|---|

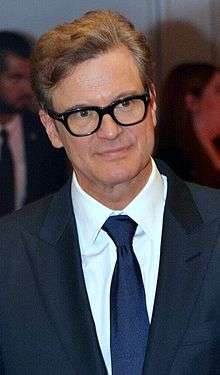

Firth (2016) | |

| Born |

Colin Andrew Firth 10 September 1960 Grayshott, Hampshire, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Citizenship |

British Italian |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1983–present |

| Spouse(s) |

Livia Giuggioli (m. 1997) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives |

Kate Firth (sister) Jonathan Firth (brother) |

| Awards | See list of awards |

Colin Andrew Firth, CBE (born 10 September 1960) is an English actor who has received an Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award, two BAFTA Awards, and three Screen Actors Guild Awards, as well as the Volpi Cup for Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival. In 2010, Firth's portrayal of King George VI in Tom Hooper’s The King's Speech won him the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Identified in the late 1980s with the "Brit Pack" of rising, young British actors, it was not until his portrayal of Fitzwilliam Darcy in the 1995 television adaptation of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice that he received more widespread attention. This led to roles in films, such as The English Patient, Bridget Jones's Diary, for which he was nominated for a BAFTA Award, Shakespeare in Love, and Love Actually. In 2009, Firth received widespread critical acclaim for his leading role in A Single Man, for which he gained his first Academy Award nomination, and won a BAFTA Award. In 2014, Firth portrayed secret agent Harry Hart in the film Kingsman: The Secret Service; he would later reprise the role in the 2017 sequel Kingsman: The Golden Circle.

His films have grossed more than $3 billion from 42 releases worldwide.[1] In 2011, Firth received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and was also selected as one of the Time 100.[2] He was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Winchester in 2007, and was made a Freeman of the City of London in 2012. He has campaigned for the rights of indigenous tribal people, and is a member of Survival International. Firth has campaigned on issues of asylum seekers, refugees' rights, and the environment. He commissioned and co-authored a scientific paper on a study into the differences in brain structure between people of differing political orientations.[3]

Early life

Firth was born in the village of Grayshott, Hampshire,[4] to parents who were both academics and teachers. His mother, Shirley Jean (née Rolles), was a comparative religion lecturer at King Alfred's College (now the University of Winchester), and his father, David Norman Lewis Firth, was a history lecturer at King Alfred's and education officer for the Nigerian Government.[5][6][7] Firth is the eldest of three children; he has a sister, Kate, an actress and voice coach, and a brother, Jonathan, an actor.[8] His maternal grandparents were Congregationalist ministers and his paternal grandfather was an Anglican priest; they performed overseas missionary work and both of his parents spent time in India.[9][10][11][12]

As a child, Firth frequently travelled due to his parents' work, spending some years in Nigeria.[13] He also lived in St. Louis, Missouri, when he was 11, which he has described as "a difficult time".[14] On returning to England, he attended the Montgomery of Alamein Secondary School (now Kings' School), which at the time was a state comprehensive school in Winchester, Hampshire. He was still an outsider and was the target of bullying. To counter this, he adopted the local working class Hampshire accent and copied his schoolmates' lack of interest in schoolwork.[15]

By the time he was 14, Firth had already decided to be a professional actor, having attended drama workshops from the age of 10. Until further education, he was not academically inclined, later saying in an interview, "I didn't like school. I just thought it was boring and mediocre and nothing they taught me seemed to be of any interest at all."[14] However, at Barton Peveril Sixth Form College in Eastleigh, he was imbued with a love of English literature by an enthusiastic teacher, Penny Edwards, and has said that his two years at Barton Peveril were "among the two happiest years of my life".[16]

After his sixth form years, Firth moved to London and joined the National Youth Theatre. There, he made many contacts in the acting world, from which he got a job in the wardrobe department at the National Theatre.[15] From there, he went on to study at Drama Centre London.[17]

Career

1983–1994, "Brit Pack" boy

Playing Hamlet in the Drama Centre end of year production, Firth was spotted by playwright Julian Mitchell, who cast him as the gay, ambitious public schoolboy Guy Bennett in the 1983 West End production of Another Country. In 1984, Firth made his film debut in the role of Tommy Judd, Guy Bennett's straight, Marxist school friend in the screen adaptation of the play (opposite Rupert Everett as Guy Bennett).[18][19] This was the start of longstanding public feud between Firth and Everett, which was later resolved.[20] He starred with Sir Laurence Olivier in Lost Empires (1986), a TV adaptation of J. B. Priestley's novel.[21]

In 1987, Firth along with other up and coming British actors such as Tim Roth, Bruce Payne and Paul McGann were dubbed the 'Brit Pack'.[22][23] That same year, he appeared alongside Kenneth Branagh in the film version of J. L. Carr's A Month in the Country.[24] Sheila Johnston observed a theme in his early works of playing those traumatised by war.[25] Firth portrayed real-life British soldier Robert Lawrence MC in the 1988 BBC dramatisation Tumbledown. Lawrence was severely injured at the Battle of Mount Tumbledown during the Falklands War, and the film details his struggles to adjust to his disability whilst confronted with indifference from the government and the public. The film attracted controversy at the time, with criticism coming from left and right ends of the political spectrum.[25] Firth's performance led to a Royal TV Society Best Actor Award and he was nominated for the 1989 BAFTA Television Award.[26] In 1989, he played the title role in Miloš Forman's Valmont, based on Les Liaisons dangereuses.[27] This was released just a year after Dangerous Liaisons and did not make a big impact in comparison. The same year, he played a paranoid, socially awkward character in Argentinian psychological thriller Apartment Zero.[28]

1995–2003, English romantic (Pride and Prejudice)

Firth finally became a household name through his role as the aloof and haughty aristocrat Mr. Darcy in the 1995 BBC television adaptation of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. He was producer Sue Birtwistle's first choice for the part, eventually being persuaded to take it despite initial reluctance as he was unfamiliar with Austen's writing.[29] Firth and co-star Jennifer Ehle began a romantic relationship during the filming of the series, which only received media attention after the couple's separation.[30] Sheila Johnston wrote that Firth's approach to the part "lent Darcy complex shades of coldness, even caddishness, in the early episodes."[25] The series was an international success and unexpectedly elevated Firth to stardom,[30] in some part due to an iconic scene in which he emerged in a wet shirt after swimming.[31] Although Firth did not mind being recognised as "a romantic idol as a Darcy with smouldering sex appeal"[32] in a role that "officially turned him into a heart-throb",[33] he expressed the wish not to be associated with Pride and Prejudice forever.[34] He was, therefore, reluctant to accept similar roles and risk becoming typecast.[15] For a time, it did seem as if Mr. Darcy would overshadow the rest of his career, and there were humorous allusions to the role in his next five movies.[35] The most notable of these was the casting of Firth as love interest Mark Darcy in the film adaptation of Bridget Jones's Diary, itself a modern-day retelling of Pride and Prejudice. Firth accepted the part as he saw it as an opportunity to lampoon his Mr. Darcy character.[36] The film was very successful[37] and critically well-liked.[38] A sequel in 2004 was mostly panned by critics[39] but was still financially successful. Firth had a supporting role in The English Patient (1996) playing the husband of Kristin Scott Thomas's character, whose jealousy about her adultery leads to both their deaths. He had parts in light romantic period pieces such as Shakespeare in Love (1998), Relative Values (2000), and The Importance of Being Earnest (2002). He appeared in several television productions, including Donovan Quick (an updated version of Don Quixote) (1999)[40] and had a more serious and villainous role as Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart in Conspiracy (2001), concerning the Nazi Wannsee Conference; Firth was nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award for his role.[41]

2003–2009, ensemble player (Love Actually, Mamma Mia!)

Firth featured in the ensemble all-star cast of Richard Curtis' Love Actually (2003), another financial success[42] which divided critics.[43][44] In contrast, that year Firth was also given solo billing as the romantic lead in Hope Springs, but the film received very poor reviews[45][46] and made little impact at the box office.[47] Firth played the painter Johannes Vermeer opposite Scarlett Johansson in the 2003 release Girl with a Pearl Earring. Some critics praised the film's gentle subtlety[48] and sumptuous visuals,[49] whilst others found it almost too restrained, tedious and bereft of emotion.[50] Nevertheless, the film received mostly favorable reviews, was moderately successful with audiences[51] and earned several awards and nominations. In 2005, Firth appeared in Nanny McPhee with Emma Thompson, a rare venture for Firth into the fantasy genre.[52] Also in 2005, he appeared in Where the Truth Lies, a return to some of Firth's darker, more intense early roles, that included a notorious scene featuring a bisexual orgy.[53] Sheila Johnston wrote that it "confounded his fans" but despite that his character "draws knowingly on that suave, cultivated persona,"[54] which could be traced from Mr. Darcy. Other films from this time included Then She Found Me (2007) with Helen Hunt and The Last Legion (2007) with Aishwarya Rai. In 2008, he played the adult Blake Morrison reminiscing on his difficult relationship with his ailing father in the film adaptation of Morrison's memoir, And When Did You Last See Your Father? The film received generally favorable reviews.[55][56] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian rated the film four out of five stars.[57] Manohla Dargis in The New York Times said: "It's a pleasure to watch Mr. Firth – a supremely controlled actor who makes each developing fissure visible – show the adult Blake coming to terms with his contradictory feelings, letting the love and the hurt pour out of him."[58] Philip French of The Observer wrote that Firth "[does] quiet agonising to perfection."[59] However, Derek Elley of Variety called the film "an unashamed tearjerker that's all wrapping and no center." While he conceded that it was "undeniably effective at a gut level despite its dramatic shortcomings," he added that "Things aren't helped any by Firth's dour perf, as his Blake comes across as a self-centered whiner, a latter-day Me Generation figure who's obsessed with finding problems when there really aren't any."[60]

The film adaptation of Mamma Mia! (2008), was Firth's first foray into musicals, and he described the experience as "a bit nerve-wracking"[61] but believed he got off lightly by being tasked with one of the less demanding songs, Our Last Summer.[62] Mamma Mia became the highest grossing British-made film of all time,[63] taking over $600 million worldwide.[64] As with Love Actually, it polarised critics in their opinions, with supporters such as Empire calling it "cute, clean, camp fun, full of sunshine, and toe tappers,"[65] whereas Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian said the film gave him a "need to vomit".[66] Carrie Rickey in The Philadelphia Inquirer described Firth's performance as "the embodiment of forced mirth."[67] That year, Firth also starred in Easy Virtue, which screened at the Rome Film Festival to excellent reviews.[68] Firth starred in Genova which premiered at the 2008 Toronto International Film Festival.[69]

In 2009, he featured in A Christmas Carol, an adaptation of Charles Dickens's novel, using the performance capture procedure, playing Scrooge's optimistic nephew Fred.[70]

2009–2011, The King's Speech, awards success

At the 66th Venice International Film Festival in 2009, Firth was awarded the Volpi Cup for Best Actor for his role in Tom Ford's directorial debut A Single Man as a college professor grappling with solitude after the death of his longtime partner. His performance earned Firth career best reviews and Academy Award, Golden Globe, Screen Actors' Guild, BAFTA, and BFCA nominations; he won the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role in February 2010.[71]

Firth starred in the 2010 film The King's Speech as Prince Albert, Duke of York/King George VI. The film details his working to overcome his speech impediment while becoming monarch of the United Kingdom at the end of 1936. At the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF),[72] the film was met with a standing ovation. The TIFF release of The King's Speech fell on Colin's 50th birthday and was called the "best 50th birthday gift".[73] On 16 January 2011, he won a Golden Globe for his performance in The King's Speech in the category of Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama. The Screen Actors Guild recognised Firth with the award for Best Male Actor for The King's Speech on 30 January 2011.[74] In February 2011, he won the best actor award at the 2011 BAFTA awards.[75] He received an Academy Award for Best Actor in a motion picture for The King's Speech on 27 February 2011.[76] It went on to gross $414,211,549 worldwide.[77]

Firth appeared as senior British secret agent Bill Haydon in the 2011 adaptation of the John le Carré novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, directed by Tomas Alfredson, also starring Gary Oldman and Tom Hardy.[78] The film gathered mostly excellent reviews.[79] The Independent described Firth's performance as "suavely arrogant" and praised the film.[80] Deborah Young in The Hollywood Reporter thought Firth got "all the best dialogue", which he delivered "sardonically".[81] Leslie Felperin in Variety wrote that all the actors brought their "A game" and Firth was in "particularly choleric, amusing form."[82] However, Peter Hitchens writing in the Daily Mail expressed reservations that Firth looked (and technically was) too young for the part, being "of the post-war generation, who escaped wartime privation," and, therefore, not "old enough or ravaged enough".[83]

2011–present

In May 2011, Firth began filming Gambit – a remake of a 1960s crime caper, taking a part played in the original by Michael Caine. It was released in the UK in November 2012 and was a financial and critical failure,[84] attracting many negative reviews.[85] Empire's Kim Newman wrote, "Firth starts out homaging Caine with his horn-rimmed cool but soon defaults to his usual repressed British clod mode",[86] whilst Time Out London called his a "likeable performance", although criticised the film overall.[87] Stephen Dalton writing in The Hollywood Reporter said "To his credit, Firth keeps his performance grounded in downbeat realism while all around are wildly mugging in desperate pursuit of thin, forced laughs.[88][89] He will appear in Rupert Everett's directorial debut The Happy Prince,[90] an Oscar Wilde biopic.[91] Firth will play Wilde's friend Reginald "Reggie" Turner. Shooting began in September 2016.[92] Firth was also expected to return for the third Bridget Jones film, which was in production in 2012.[93][94]

In May 2013, it was announced that Firth had signed to co-star with Emma Stone in Woody Allen's romantic comedy Magic in the Moonlight, set in the 1920s, shot on the French Riviera.[95]

In 2015, Firth starred as Harry Hart in the spy action film Kingsman: The Secret Service which was a commercial success and received generally positive reviews.[96] Kingsman: The Secret Service earned a gross of $414.4 million, against a budget of $81 million.[97]

In June 2015, he was reported to be filming the story of Donald Crowhurst in The Mercy, in which he stars as the yachtsman alongside Rachel Weisz, David Thewlis, and Jonathan Bailey.[98]

In 2016, Firth reprised his popular role as Mark Darcy in Bridget Jones's Baby, which fared much better with audiences and critics than the second in the series ("Bridget Jones: Edge of Reason"). Also in 2016, Firth portrayed American editor Max Perkins in the critically acclaimed Genius alongside Jude Law as author Thomas Wolfe.[99][100] The film, which is based on A. Scott Berg's biography Max Perkins: Editor of Genius.

In 2017, he reprised his role as Jamie from 2003's Love Actually in the television short film Red Nose Day Actually, by original writer and director Richard Curtis.[101] Also that year, Firth returned as Harry Hart in the sequel Kingsman: The Golden Circle.[102]

In 2018, Firth again portrayed Harry Bright in the sequel to Mamma Mia!, Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again.[103] That year, he will also appear as William Weatherall Wilkins, president of the Fidelity Fiduciary Bank, in the film Mary Poppins Returns, and play British naval commander David Russell in Thomas Vinterberg's Kursk, a film about the true story of the 2000 Kursk submarine disaster, in which he stars alongside Matthias Schoenaerts.[104][105][106] Filming began in April 2017.[107]

Other work

Firth's first published work, "The Department of Nothing", appeared in Speaking with the Angel (2000).[108] This collection of short stories was edited by Nick Hornby[109] and was published to benefit the TreeHouse Trust,[110] in aid of autistic children. Firth had previously met Hornby during the filming of the original Fever Pitch.[111][112] Colin Firth contributed with his writing for the book, We Are One: A Celebration of Tribal Peoples, released in 2009.[113] The book explores the cultures of peoples around the world, portraying both their diversity and the threats that they face. It features contributions from many Western writers, such as Laurens van der Post, Noam Chomsky, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and also from indigenous people, such as Davi Kopenawa Yanomami and Roy Sesana. The royalties from the sale of this book go to the indigenous rights organisation, Survival International.

Firth was an executive producer for the film In Prison My Whole Life, featuring Noam Chomsky and Angela Davis. The film was selected to the 2007 London Film Festival and the 2008 Sundance Film Festival.[114]

In December 2010, Firth was guest editor on BBC Radio 4's Today programme, during which he commissioned research to scan the brains of politicians to see if there were any differences depending on political leanings.[115] He was then credited as one of four co-authors of an academic paper into human brains, the others being University College London researchers.[116][117] The results of the study suggested that conservatives have greater amygdala volume and liberals have greater volume in their anterior cingulate cortex.

In 2012, Firth's audiobook recording of Graham Greene's The End of the Affair was released at Audible.com.[118] The production was awarded Audiobook of the Year at the 2013 Audie Awards.[119]

In 2012, he co-founded Raindog Films with British music industry executive and entrepreneur Ged Doherty.[120] its first feature, Eye in the Sky, was released theatrically in April 2016.

Activism

Firth has been a long-standing supporter of Survival International, a non-governmental organisation that defends the rights of tribal peoples.[121] Speaking in 2001, he said, "My interest in tribal peoples goes back many years... and I have supported [Survival] ever since."[122] In 2003, during the promotion of the film Love Actually, he spoke in defence of the tribal people of Botswana, condemning the Botswana government's eviction of the Gana and Gwi people (San) from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. He says of the San, "These people are not the remnants of a past era who need to be brought up to date. Those who are able to continue to live on the land that is rightfully theirs are facing the 21st century with a confidence that many of us in the so-called developed world can only envy."[121] He has also backed a Survival International campaign to press the Brazilian government to take more decisive action in defence of the Awá-Guajá people, whose land and livelihood is critically threatened by the actions of loggers.[123]

As a supporter of the Refugee Council, Firth was involved in a campaign to stop the deportation of a group of 42 Congolese asylum seekers, expressing concerns in open letters to The Independent and The Guardian that they faced being murdered on their return to the Democratic Republic of Congo.[124][125][126] Firth said: "To me, it's just basic civilisation to help people. I find this incredibly painful to see how we dismiss the most desperate people in our society. It's easily done. It plays to the tabloids, to the Middle-England xenophobes. It just makes me furious. And all from a government we once had such high hopes for".[127] Four of the asylum seekers were given a last-minute reprieve from deportation.[128]

Firth, along with other celebrities, has been involved in the Oxfam[129] global campaign Make Trade Fair, focusing on trade practices seen as especially unfair to third world producers including dumping, high import tariffs, and labour rights.[130][131][132] He has further contributed to this cause by opening (with a few collaborators) an eco-friendly shop in West London, Eco.[133] The shop offers fair trade and eco-friendly goods, as well as expert advice on making spaces more energy efficient. In October 2009, at the London Film Festival, Firth launched a film and political activism website, Brightwide (since decommissioned), along with his wife Livia.[134][135]

During the 2010 general election, Firth announced his support for the Liberal Democrats, having previously been a Labour supporter, citing asylum and refugees' rights as a key reason for his change in affiliation.[136] In December 2010, Firth publicly dropped his support of the Liberal Democrats, citing their U-turn on tuition fees as one of the key reasons for his disillusionment. He also said that while he no longer supports the Liberal Democrats, he is currently unaffiliated.[137] Firth appeared in literature to support changing the British electoral system from first-past-the-post to alternative vote for electing members of parliament to the House of Commons in the unsuccessful Alternative Vote referendum in 2011.[138]

In 2009, Firth joined the 10:10 project, supporting the movement calling for people to reduce their carbon footprint. In 2010, Colin endorsed the "Roots & Shoots"[139] education programme in the UK run by the Jane Goodall Institute (UK).

Personal life

In 1989, Firth began a relationship with Meg Tilly, his co-star in Valmont. They had a son, William Joseph "Will" Firth, in 1990.[140] The family moved to the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, Canada. Firth's acting career slowed down until they broke up in 1994, and he returned to the UK.[141] In 1997, Firth married Italian film producer and director Livia Giuggioli.[142] They have two sons, Luca (born March 2001) and Matteo (born August 2003).[15] The family now live in both Chiswick, London and Umbria, Italy.[143][144] Firth started to learn Italian when he and Giuggioli began to date and is now fluent in the language.

Firth was awarded an honorary degree on 19 October 2007, from the University of Winchester.[145][146] On 13 January 2011, he was presented with the 2,429th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[147] In April 2011, Time magazine included Firth in its list of the world's 100 Most Influential People.[148] Firth was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2011 Birthday Honours for services to drama,[149][150] and made a Freeman of the City of London on 8 March 2012.[151]

A vocal opponent of the United Kingdom leaving the European Union (Brexit), following the referendum result and ensuing uncertainty over rights of non EU citizens, Firth applied for "dual citizenship (British and Italian)" in 2017 in order to "have the same passports as his wife and children".[152][153] The Italian interior minister, Marco Minniti, announced his application had been approved on 22 September 2017.[154] Firth added, “I will always be extremely British (you only have to look at or listen to me).”[155]

Awards

Note: The year given is the year of the ceremony

Academy Awards

| Year | Award | Performance | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Best Actor | A Single Man | Nominated |

| 2011 | The King's Speech | Won |

Golden Globe Awards

| Year | Award | Performance | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | A Single Man | Nominated |

| 2011 | The King's Speech | Won |

BAFTA Awards

| Year | Award | Performance | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Academy Television Awards | |||

| 1989 | Best Lead Actor | Tumbledown | Nominated |

| 1996 | Pride and Prejudice | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Awards | |||

| 2002 | Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Bridget Jones's Diary | Nominated |

| 2010 | Best Actor in a Leading Role | A Single Man | Won |

| 2011 | The King's Speech | Won | |

Primetime Emmy Award

| Year | Award | Performance | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or Movie | Conspiracy | Nominated |

Screen Actors Guild Awards

| Year | Award | Performance | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture | The English Patient | Nominated |

| 1999 | Shakespeare in Love | Won | |

| 2010 | Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role | A Single Man | Nominated |

| 2011 | The King's Speech | Won | |

| Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture | Won |

Critics' Choice Awards

| Year | Award | Performance | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Best Actor | A Single Man | Nominated |

| 2011 | The King's Speech | Won |

Other awards

| Year | Association | Award | Performance | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Dorian Awards | Film Performance of the Year | A Single Man | Won |

| 2009 | Venice Film Festival | Volpi Cup for Best Actor | Won |

See also

References

- ↑ "Colin Firth's Box Office Stats". The Movie Times. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ "Full List – The 2011 TIME 100", Time, 21 April 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ "Colin Firth credited in brain research". BBC News. 5 June 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ↑ "Person Details for Colin A Firth, "England and Wales Birth Registration Index, 1837-2008" — FamilySearch.org".

- ↑ "Actor Colin Firth is perhaps bes". Firthessence.net. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "Colin Firth's Lineage". Firthessence.net. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "Colin Firth Biography (1960–)". Filmreference.com. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Karen. "Real Magazine interview with Colin McErlean (Aug 2002)". Firth.com. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ lmw (7 May 2001). "Colin Firth – Fresh Air interview 2001". Hem.passagen.se. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Karen. "Colin Firth: Bridget Jones' Sweetie Would Rather Play Bad Guys". Spring.net. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Fresh Air from WHYY. "British Actor Colin Firth". NPR. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Karen (18 May 2002). "Globe and Mail – The Other Face of Colin Firth (May 18, 2002)". Firth.com. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Stated in interview on Inside the Actors Studio, 2011

- 1 2 "Press Releases Colin Firth Desert Island DiscsCategory: Radio 4". BBC Press Office releases. BBC. 4 December 2005. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Biography.com

- ↑ Jason Rainbow (15 June 2010). "College 'saved me', reveals actor Colin Firth". FE News. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ "Colin Firth: People". People. 2013 Time Inc. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "Another Country". BFI Film. BFI. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ↑ Jacques, Adam (23 March 2014). "How we met: Colin Firth & Julian Mitchell". The Independent. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ↑ Fenton, Andrew (27 March 2008). "Colin Firth has ended his feud with Rupert Everett". Herald Sun. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

"Everett publicly branded Firth 'boring' and classified him as 'a ghastly guitar-playing redbrick socialist who was going to give his first half-million away to charity'. 'We didn't get along very well the first time we worked together, Firth says simply. 'I think he was probably terribly threatened because I was an awful lot better than him.'" There is some truth to this because in Everett's 2006 autobiography, the gay actor admits he fancied, and felt threatened by, Firth at the time.

- ↑ "Lose Yourself With Colin Firth in 'Lost Empires' | BBC America". BBC America. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Van Poznak, Elissa (January 1987). "The Brit Pack". The Face. No. 81. pp. 36–39. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Brit Pack". Brucepayne.de. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet. "Film Festival; 'Month in the Country,' From Director of 'Cal'". Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- 1 2 3 Shuaib, Keith. "Tumbledown (1988)". BFI Screenonline. BFI. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "Television Actor in 1989". BAFTA Awards. BAFTA. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Szabo, Julia (November 1989). "Going Firth Class". Mademoiselle. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ Andrew, Geoff. "Apartment Zero". Time Out London. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Grimes, William (14 January 1996). "An Austen Tale of Sex and Money in Which Girls Kick Up Their Heels". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- 1 2 Steiner, Susie (31 March 2001). "Twice Shy". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ Me Sexy? only to that crazy Bridget Jones: Vanity Fair

- ↑ James, Caryn (29 July 2007). "Austen Powers: Making Jane Sexy". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- ↑ Ryan, Tom (6 March 2004). "Renaissance man". The Age. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ↑ Passero, Kathy (December 1996). "Pride, Prejudice and a Little Persuasion". A&E Monthly Magazine.

- ↑ Petterson, John (1 January 2011). "Colin Firth has left his posh acting peers in the dust. Give him the Oscar for The King's Speech now". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Faillaci, Sara (16 October 2003). "Me Sexy?". Vanity Fair (Italy).

- ↑ "Bridget Jones's Diary box office". Box Office Mojo. IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bridget Jones's Diary Reviews top critics". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster, Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bridget Jones – The Edge of Reason (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster, Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Johnston, Sheila. "Firth, Colin (1960–)". BFI Screenonline. BFI. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "Colin Firth". Television Academy.

- ↑ "Love Actually at TheNumbers.com". The-numbers.com. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ↑ Wloszczyna, Susan (5 November 2003). "USA Today review". USA Today. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ↑ A. O. SCOTT <p> (7 November 2003). "New York Times review". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Peter (21 July 2008). "Hope Springs Our Review". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

It made me want to tumble off the red plush seats, curl up into a foetal ball and mew like a maltreated kitten

- ↑ Smith, Anna. "Hope Springs Review". Empire. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ "Hope Springs box office". Box Office Mojo. IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (26 December 2003). "Girl with a Pearl Earring, December 26, 2003". Roger Ebert.com. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ McCarthy, Todd. "Girl With a Pearl Earring". Variety reivews, Mon, Sep. 1, 2003. Variety Media, LLC. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (8 December 2003). "Seven Holiday Treats". Time Magazine Monday, Dec. 08, 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "Girl With Pearl Earring (2003) ratings". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster, Inc. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Felperin, Leslie (2005-10-24). "Film Review: 'Nanny McPhee'". Variety. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Johnston, Sheila (2005-11-26). "Is that Mr Darcy taking part in an orgy?". ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Johnston, Sheila (26 November 2005). "Is that Mr Darcy taking part in an orgy?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "When Did You Last See Your Father?". rottentomatoes.com. 6 June 2008.

- ↑ "Stuck". Metacritic.

- ↑ Peter Bradshaw. "And When Did You Last See Your Father?". The Guardian.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla (6 June 2008). "As a Father Nears Death, a Son Grows No Closer". The New York Times.

- ↑ Philip French. "All about my father". The Guardian.

- ↑ Derek Elley. "When Did You Last See Your Father?". Variety.

- ↑ Ivan-Zadeh, Larushka. "Mamma Mia! Firth is a super trooper". Metro, Sunday 6 Jul 2008. Associated Newspapers Limited. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Sutherland, Claire (10 July 2008). "Colin Firth talks about the challenges of Mamma Mia!". Herald Sun. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Irvine, Chris (30 October 2008). "Mamma Mia becomes highest grossing British film". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

The film has made £66,995,224 in the UK, beating Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone.

- ↑ "Mamma Mia! gross". Box Office Mojo. IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "Empire review". Archived from the original on 3 March 2010.

- ↑ Peter Bradshaw. "Mamma Mia!". The Guardian.

- ↑ "'Mamma Mia,' here we go again – this time on screen". philly-archives.

- ↑ "Easy Virtue brings British humour to Rome Film Festival". Reuters. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ Colin Firth, Genova Interview. AOL Entertainment Canada Archived 24 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Colin Firth's discomfort in skin-tight spandex for A Christmas Carol animated movie". The Telegraph. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bafta wins for Carey Mulligan and Colin Firth". BBC News. 21 February 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ↑ Evans, Ian (2010), Tom Hooper, Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush at The King's Speech premiere at the 35th Toronto International Film Festival, DigitalHit.com, retrieved 3 August 2011

- ↑ Friedman, Roger (11 September 2010). "Colin Firth Gets Best 50th Birthday Gift". Showbiz 411. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ↑ Whitworth, Melissa (17 January 2011). "Golden Globes 2011: Colin Firth wins Best Actor as The Social Network takes four awards". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ↑ Brown, Mark (14 February 2011). "Baftas 2011: The King's Speech sweeps the board". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ↑ Singh, Anita (28 February 2011). "Colin Firth takes Oscars crown as British film proves mother knows best". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ↑ "The King's Speech box office statistics". Box Office Mojo. IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ "Benedict Cumberbatch Joins 'Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy'". 16 August 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Tinker Tailor Soldier, Spy 2011". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster, Inc. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Romney, Johnathan (18 September 2011). "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (15)". The Independent. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Young, Deborah (9 May 2011). "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy: Venice Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Felperin, Leslie (5 September 2011). "Venice Film Festival Review Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy". Variety. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Hitchens, Peter (21 September 2011). "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Travesty". Daily Mail. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ "Gambit (2013) – International Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "Gambit (2012)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Newman, Kim (November 2012). "Empire's Gambit Movie Review". Empire. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Johnston, Trevor (8 November 2012). "Gambit (12A)". Time Out London. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Dalton, Stephen (11 July 2012). "The Bottom Line Starry art-heist remake is more clumsy sketch than Old Master". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ "Gambit 2012". Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ "The Happy Prince 2014". Internet Move Database. IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Roxborough, Scott (21 May 2012). "Cannes 2012: Rupert Everett to Make Directorial Debut With Oscar Wilde Biopic". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Rupert Everett, Colin Firth begin filming Oscar Wilde biopic at screendaily.com. Retrieved 28 December 2016

- ↑ Press, Associated (20 September 2012). "'Bridget Jones's Baby' Script Taking Shape: Renee Zellweger, Colin Firth And Hugh Grant Expected To Return". HuffPost. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ "Bridget Jones's Baby (2013)". IMDb. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Ben Child. "Colin Firth to star in Woody Allen's next film, alongside Emma Stone". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Kingsman: The Secret Service". IMDb. 13 February 2015.

- ↑ "Kingsman: The Secret Service (2015)". Box Office Mojo. 1 March 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ↑ "PICTURES: Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz on a Teignmouth film set". Western Morning News. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Khomami, Nadia (6 November 2012). "Colin Firth and Jude Law to star in upcoming literary drama Genius". The Telegraph.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ McClintock, Pamela (2 July 2013). "Berlin 2013: Colin Firth, Jude Law's 'Genius' Sells Around the World (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Red-nose-day-love-actually-sequel-what-happened-to-every-character-in-the-comic-relief-special" https://www.standard.co.uk/stayingin/tvfilm/red-nose-day-love-actually-sequel-what-happened-to-every-character-in-the-comic-relief-special-a3499016.html

- ↑ Shoard, Catherine (11 July 2016). "Colin Firth back from the dead for Kingsman 2". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ↑ Zach Seemayer (June 22, 2017). "EXCLUSIVE: Dominic Cooper Dishes on Returning for 'Mamma Mia 2': It's 'a Phone Call I've Been Waiting For'". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

The actor will be joining a slew of big-name stars who are returning to the fun franchise, including Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Amanda Seyfried and Pierce Brosnan.

- ↑ Kroll, Justin (10 February 2017). "Colin Firth Joins Emily Blunt in 'Mary Poppins' Sequel (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ↑ "Colin Firth to Star in Submarine Disaster Movie 'Kursk'". The Hollywood Reporter. 25 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ↑ "Lea Seydoux Boards EuropaCorp Submarine Drama 'Kursk' – Berlin". Deadline Hollywood. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ↑ "Tournage. Colin Firth à Brest pour le film "Kursk"". Le Télégramme (in French). 2 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ↑ lmw. "Colin Firth Career Timeline: Department of Nothing". Hem.passagen.se. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "Nick Hornby". Penguin.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "TreeHouse". Penguin.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ "Colin Firth Biography". Tiscali.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ malcolmgsw (4 April 1997). "Fever Pitch (1997)". IMDb.

- ↑ "We Are One". Survival International. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ (a) In Prison My Whole Life Sundance Film Festival website; (b) Official Website of the film (c) Review of In Prison My Whole Life. (Registration required) at screendaily.com

- ↑ "Colin Firth credited in brain research", BBC News, 5 June 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Kanai, Ryota (2011). "Political Orientations Are Correlated with Brain Structure in Young Adults". Current Biology. 21: 677–680. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.017.

- ↑ "Brain and behaviour: The voter's grey matter" 23 June 2011, Nature

- ↑ "Colin Firth lends voice to classic novel reading". CBS This Morning. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ "The Audies 2013". Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ↑ "Ged Doherty". LinkedIn. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- 1 2 "'Love Actually' star Colin Firth condemns Bushman evictions". Survival International. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ↑ "Audio". Survival International. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008.

- ↑ Chamberlain, Gethin (22 April 2012). "'They're killing us': world's most endangered tribe cries for help". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Firth, Colin (26 February 2007). "Britain's shameful deportations of asylum seekers". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ Colin Firth (26 February 2007). "We must stop a deportation that is likely to end in murder". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ↑ "Colin Firth voices outrage at deportations to Congo". Refugee Council, 27 February 2007. Refugee Council. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ↑ Andrew Johnson (26 February 2007). "Colin Firth makes plea for nurse 'facing murder' in Congo". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ↑ Damian Spellman (27 February 2007). "Firth's intervention saves nurse from deportation". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ↑ "The King's Speech Star to Auction Himself for Charity". EF News International. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- ↑ "Make Trade Fair". Oxfam International. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009.

- ↑ "Celebrities present 18 million-strong Make Trade Fair petition to World Trade boss in Hong Kong". Oxfam International. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008.

- ↑ "Colin Firth Profile in the Independent". firth.com.

- ↑ Lisa Grainger (17 November 2007). "Colin Firth's New Eco-Store". The Times. London. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Brightwide Archived 20 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. web site. Meanwhile out of service. Retrieved 15 July 2015

- ↑ Adam Dawtrey (22 September 2009). "The Rebirth of Colin Firth". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Backers, Celebrity (16 March 2010). "Colin Firth on why he's stopped voting Labour and now supports the Lib Dems". Libdemvoice. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Wintour, Patrick (14 December 2010). "Colin Firth: I no longer support the Liberal Democrats". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Benjamin Zephaniah 'airbrushed from Yes to AV leaflets'". BBC News. 3 April 2011.

- ↑ Endorsement from Colin Firth Roots & Shoots

- ↑ "William Joseph Firth(1990)". Archived from the original on 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Johnston, Sheila. "Firth, Colin (1960–)". BFI Screenonline. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Steiner, Susie (31 March 2001). "Twice Shy". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ Eden, Richard (17 June 2012). "Colin Firth's wife Livia refuses to let the sun set on her eco dream". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ O'Ceallaigh, John (30 November 2012). "Livia Firth's travelling life". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "Colin Firth Receives Honorary Degree". starpulse. 26 October 2007. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ↑ "Colin Firth – Honorary speech 2007 Graduation at University of Winchester". YouTube.

- ↑ "Colin Firth wins a star on Hollywood's Walk of Fame". The Guardian. London. 14 January 2011. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013.

- ↑ "The 2011 TIME 100". Time. 21 April 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ↑ "No. 59808". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 June 2011. p. 7.

- ↑ "Main list of the 2011 Queen's birthday honours recipients" (PDF). BBC News UK. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ↑ "Colin Firth becomes Freeman of the City of London" Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. 1 March 2012, News release at City of London website

- ↑ "British actor Colin Firth gets Italian citizenship after Brexit vote". Muslim Global. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ Squires, Nick (23 May 2017). "Colin Firth applies for Italian citizenship". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ "British star Colin Firth becomes Italian citizen following Brexit decision". Fox News Channel. 2017-09-23. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ↑ "Colin Firth becomes Italian citizen amid 'uncertainty' but says he will always be 'extremely British'". The Telegraph. 30 April 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Colin Firth. |

- Colin Firth on IMDb

- Raindog Films on IMDbPro (subscription required)

- Colin Firth at the BFI's Screenonline

- Colin Firth at AllMovie

Interviews

- "Colin Firth talks action movie debut in 'Kingsman: The Secret Service'" (transcript). Interview with Nina Terrero. Entertainment Weekly. May 2014.

- "Colin Firth: A Life in Pictures". BAFTA interview. BAFTA Guru. January 2012. Archived from the original (audio) on 15 April 2017.

- "Q&A: Actor Colin Firth" (transcript). Interview with Jasper Rees. The Arts Desk. February 2011.

- "The NS Interview: Colin Firth" (transcript). Interview with Sophie Elmhirst. New Statesman. June 2010. (Extended interview (transcript)).

Further reading

- Teeman, Tim (20 September 2007). "Colin Firth's Darcy Dilemna [sic]". Screen. Times2. London. pp. 11–12. Full text (titled 'Darcy Simply Won't Die') – via TimTeeman.com. Retrieved 14 April 2017.