Trevor Howard

| Trevor Howard | |

|---|---|

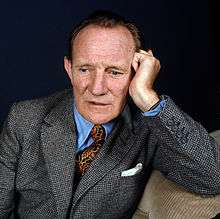

Trevor Howard, 1973 | |

| Born |

Trevor Wallace Howard-Smith 29 September 1913[1] Cliftonville, Kent, England |

| Died |

7 January 1988 (aged 74) Arkley, Barnet, Hertfordshire, England |

| Resting place | Saint Peter's Church, Arkley |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1934–1988 |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Cherry (m. 1944–1988; his death) |

Trevor Wallace Howard-Smith (29 September 1913 – 7 January 1988)[2] was an English film actor. After varied stage work, he achieved star status with his role in the film Brief Encounter (1945), followed by The Third Man (1949). This led to many popular appearances on film and TV.

Biography

Early life

Howard was born in Cliftonville, Kent, England the son of Mabel Grey (Wallace) and Arthur John Howard.[3] Although Howard later claimed to have been born in 1916 - the year quoted by most reference sources - he was born in 1913 (this is supported by school and other records).[4][5] His father was an insurance underwriter for Lloyds of London and he spent the first eight years of his life travelling around the world.[6][7] He was educated at Clifton College (to which he left in his will a substantial legacy for a drama scholarship) and at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA).[8] In 1933, at the end of his first year, he was chosen as best actor in his class for his performance as Benedict in a school production of Much Ado About Nothing. While Howard was still studying, he made his professional debut at the Gate Theatre in Revolt in a Reformatory (1934).

When he left school he worked regularly on stage, including in Sheridan's The Rivals, several performances at Stratford-upon-Avon, and in a two-year run in the original production of French Without Tears.[9][10]

Second World War

Although stories of his courageous wartime service in the British Army's Royal Corps of Signals earned him much respect among fellow actors and fans alike, files held in the Public Record Office reveal that he had actually been discharged from the British Army in 1943 for mental instability and having a "psychopathic personality". The story, which surfaced in Terence Pettigrew's biography of the actor, published by Peter Owen in 2001, was initially denied by Howard's widow, actress Helen Cherry. Later, confronted with official records, she told The Daily Telegraph (24 June 2001) that Howard's mother had claimed he was a holder of the Military Cross. She added her husband "had nothing to be ashamed of" with an honourable military record.[11]

Early films

After a theatrical role in The Recruiting Officer (1943), Howard began working in films with an uncredited part The Way Ahead (1944), directed by Carol Reed.[12] He was in a big stage hit, A Soldier for Christmas (1944) and a production of Eugene O'Neill's Anna Christie (1944). Howard received his first credit for The Way to the Stars (1945), playing a pilot.[13]

Stardom

Howard's performance in The Way Ahead came to the attention of David Lean, who was looking for someone to play the role of Alec in Brief Encounter (1945). Lean recommended him to Noël Coward, who agreed with the suggestion, and the success of the film launched Howard's film career.[14]

He followed it with I See a Dark Stranger (1946) with Deborah Kerr, and Green for Danger (1947), starring Alastair Sim. Both films were successful as was They Made Me a Fugitive (1947). That year British exhibitors voted Howard the 10th most popular British star at the box office.[15] So Well Remembered (1948) was made with American talent and money and was a hit in Britain but lost money overall.

Howard was reunited with Lean for The Passionate Friends (1949), but the film was not a success. However, The Third Man (1949), which Howard starred in alongside Orson Welles and Joseph Cotten for Carol Reed from a story by Graham Greene, was a huge international success, and became the film of which Howard was most proud.[16] During filming in Vienna, Howard was keen to get to his favourite bar for a drink as soon as filming had finished for the evening. On one occasion Howard was in too much of a hurry to change out of his uniform as a British Army major. After a few drinks, he got into an argument and attracted the attention of a real major, who ordered the Military Police to arrest Howard as an impostor. Howard was forced to apologise and was summoned to appear before the British commanding general, Sir Alexander Galloway.[17]

Howard was the lead in Golden Salamander (1950) and played Peter Churchill in Odette (1950) with Anna Neagle, a big hit in Britain. It was directed by Herbert Wilcox who put Howard under contract.[18] He loaned Howard to Betty Box and Ralph Thomas to make The Clouded Yellow (1950), a popular thriller with Jean Simmons. These films helped Howard be voted the 2nd biggest British star at the box office in 1951[19] and the 5th biggest (and eleventh bigger over-all) in 1951.[20]

Howard was reunited with Carol Reed for Outcast of the Islands (1952) and he made a war film, Gift Horse (1952). That year he made his final appearance in Britain's ten most popular actors, coming in at number nine.[21] He was in another adaptation of a Graham Greene story, The Heart of the Matter (1953). Greene also wrote and produced Howard's next film, the British-Italian The Stranger's Hand (1954). Howard was in a French movie, The Lovers of Lisbon (1955), then supported Jose Ferrer in a war film from Warwick Pictures, The Cockleshell Heroes (1955), which was popular in Britain.[22]

International star

Howard's first Hollywood film was Run for the Sun (1956), where he played a villain to Richard Widmark's hero. He made a cameo in Around the World in 80 Days (1956) and again played a villain to an American star, Victor Mature, in Warwick's Interpol (1957).

Howard starred in Manuela (1957) then supported William Holden in Carol Reed's The Key (1958), for which he received the Best Actor award from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts. When William Holden dropped out of the lead of The Roots of Heaven (1958), Howard stepped in - the star part in a Hollywood film (although top billing went to Errol Flynn).

After a thriller Moment of Danger (1960) he was in Sons and Lovers (1960), for which he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. He was nominated for a BAFTA on four other occasions. and received two other Emmy nominations, one as a lead and the other as a supporting actor. He also received three Golden Globe Award nominations.

Howard was reunited with Holden for The Lion (1962). He was Captain Bligh to Marlon Brando's Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty (1962). He was in a TV movie production of Hedda Gabbler (1962)[23] and played the title prime minister in "The Invincible Mr Disraeli" (1963), an episode of the Hallmark Hall of Fame for which he won an Emmy award for his role then supported Robert Mitchum in Man in the Middle (1964) and Cary Grant in Father Goose (1964). After a cameo in Operation Crossbow (1965), Howard supported Frank Sinatra in Von Ryan's Express (1965), Brando and Yul Brynner in Morituri (1965), and Rod Taylor in The Liquidator (1965). After a cameo in The Poppy Is Also a Flower (1966) he made two movies with Brynner, Triple Cross (1966) and The Long Duel (1967).

Character actor

Howard had a change of pace supporting Hayley Mills in Pretty Polly (1968). He went back to military roles: The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), as Lord Cardigan, and Battle of Britain (1969). He had support parts in Lola (1969) and Ryan's Daughter (1970), the latter for David Lean.

He made a Swedish film The Night Visitor (1971) then settled into a career as a character actor: To Catch a Spy (1971), supporting Kirk Douglas; Mary, Queen of Scots (1971), as Sir William Cecil; Kidnapped (1971); Pope Joan (1972); Ludwig (1972); The Offence (1972), with Sean Connery; A Doll's House (1973), for Joseph Losey; Who? (1974), supporting Elliott Gould; and Catholics (1974) for British TV.

He was in some horror films - Craze (1974), Persecution (1974) - and the more prestigious 11 Harrowhouse (1974). In The Count of Monte Cristo (1975) he mentored Richard Chamberlain. He was military men in Hennessy (1975) and Conduct Unbecoming (1975). Around this time he complained that he had to work so hard because of the high rate of tax in Britain.[24]

Howard could be found in Albino (1976), shot in Rhodesia; The Bawdy Adventures of Tom Jones (1976); Aces High (1976); Eliza Fraser (1976), shot in Australia[25]; The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977); and Stevie (1978). He was one of many names in Superman (1978), Hurricane (1979), Meteor (1979) and The Sea Wolves (1980). He appeared in a TV series Shillingbury Tales (1980-81) and had a rare lead in Sir Henry at Rawlinson End (1980).

Howard was also top billed in Windwalker (1981). He and Celia Johnson from Brief Encounter were reunited in Staying On (1980) for British TV.

Final films

Howard managed to appear in some prestigious movies towards the end of his career: The Deadly Game (1982), The Missionary (1982), Gandhi (1982), George Washington (1984), Shaka Zulu (1986), Dust (1985) and Peter the Great (1986).

At the time of filming White Mischief (1988) on location in Kenya during 1987, Howard was seriously ill and suffering from alcoholism. The company wanted to sack him, but co-star Sarah Miles was determined that Howard's distinguished film career would not end that way. In an interview with Terence Pettigrew for his biography of Howard, Miles describes how she gave an ultimatum to the executives, threatening to quit the production if they got rid of him.[26]

The Dawning (1988) was his final film. One of his strangest films, and one he took great delight in, was Vivian Stanshall's Sir Henry at Rawlinson End (1980), in which he played the title role. His wife, Helen Cherry, starred with him in the film 11 Harrowhouse (1974).

Throughout his film career Howard insisted that all his contracts include a clause excusing him from work whenever a cricket Test Match was being played.[27]

Howard recorded two Shakespeare performances, the first, recorded in the 1960s, was as Petruchio opposite Margaret Leighton's Kate in Caedmon Records' complete recording of The Taming of the Shrew; the second was in the title role of King Lear for the BBC World Service in 1986.

Honors

A British government document leaked to the Sunday Times in 2003 shows that Howard was among almost 300 individuals to decline official honours. He declined a CBE in 1982.[28]

Personal life

He married Helen Cherry. He died on 7 January 1988 from hepatic failure and cirrhosis of the liver in Arkley, Barnet, aged 74.[29]

Complete filmography

- The Way Ahead (1944) as Officer on Ship (uncredited)

- The Way to the Stars (1945) as Squadron Leader Carter

- Brief Encounter (1945) as Alec Harvey

- I See a Dark Stranger (1946) as David Baynes

- Green for Danger (1946) as Dr. Barnes

- They Made Me a Fugitive (1947) as Clem

- So Well Remembered (1947) as Richard Whiteside

- The Passionate Friends (1949) as Professor Steven Stratton

- The Third Man (1949) as Maj. Calloway

- Golden Salamander (1950) as David Redfern

- Odette (1950) as Captain Peter Churchill / Raoul

- The Clouded Yellow (1950) as Maj. David Somers

- Lady Godiva Rides Again (1951) as Guest at Theater Accepting Program (uncredited)

- Outcast of the Islands (1952) as Peter Willems

- Gift Horse (1952) as Lieutenant Commander Hugh Algernon Fraser

- The Heart of the Matter (1953) as Harry Scobie

- La mano dello straniero (1954) as Major Roger Court

- Les amants du Tage (1955) as Inspector Lewis

- The Cockleshell Heroes (1955) as Captain Thompson

- Run for the Sun (1956) as Browne

- Around the World in 80 Days (1956) as Denis Fallentin – Reform Club Member

- Interpol (1957) as Frank McNally

- Manuela (1957) as James Prothero

- A Day in Trinidad, Land of Laughter (1957 short) as Narrator

- The Key (1958) as Captain Chris Ford

- The Roots of Heaven (1958) as Morel

- Malaga (1960) as John Bain

- Sons and Lovers (1960) as Walter Morel

- The Lion (1962) as John Bullit

- Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) as Captain William Bligh

- Man in the Middle (1963) as Major John Darryl Kensington

- Father Goose (1964) as Houghton

- Operation Crossbow (1965) as Professor Lindermann

- Von Ryan's Express (1965) as Maj. Eric Fincham

- Morituri (1965) as Colonel Statter

- The Liquidator (1965) as Mostyn

- The Poppy Is Also a Flower (1966) as Sam Lincon

- Triple Cross (1966) as Distinguished Civilian

- The Long Duel (1967) as Young

- Pretty Polly (1967) as Robert Hook

- The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) as Lord Cardigan

- Battle of Britain (1969) as Air Vice-Marshal Sir Keith Park

- Twinky (1969) as Lola's Grandfather

- Ryan's Daughter (1970) as Father Hugh Collins

- The Night Visitor (1971) as The Inspector

- To Catch a Spy (1971) as Sir Trevor Dawson

- Mary, Queen of Scots (1971) as William Cecil

- Pope Joan (1972) as Pope Leo

- Ludwig (1972) as Richard Wagner

- The Offence (1972) as Detective Superintendent Cartwright

- Kidnapped (1973) as Lord Advocate Grant

- A Doll's House (1973) as Dr Rank

- Who? (1973) as Colonel Azarin

- Catholics (1973) as The Abbot

- Craze (1974) as Supt. Bellamy

- 11 Harrowhouse (1974) as Clyde Massey

- Persecution (1974) aka Sheba, The Graveyard, The Terror of Sheba as Paul Bellamy

- Cause for Concern (1974) as Narrator

- The Count of Monte Cristo (1975 TV movie) as Abbe Faria

- Hennessy (1975) as Commander Rice

- Conduct Unbecoming (1975) as Colonel Benjamin Strang

- Albino (1976) as Johannes

- The Bawdy Adventures of Tom Jones (1976) as Squire Western

- Aces High (1976) as Silkin

- Eliza Fraser (1976) as Captain Foster Fyans

- The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977) as Sir Hector

- Babel Yemen (1977 short) as Narrator

- Slavers (1978) as Alec Mackenzie

- Stevie (1978) as The Man

- Superman (1978) as 1st Elder

- The Spirit of Adventure: Night Flight (1979 TV movie) as Riviere

- Hurricane (1979) as Father Malone

- Meteor (1979) as Sir Michael Hughes

- Flashpoint Africa (1980) as Programme Controller

- The Shillingbury Blowers (1980) as Dan 'Saltie' Wicklow

- The Sea Wolves (1980) as Jack Cartwright

- Sir Henry at Rawlinson End (1980) as Sir Henry Rawlinson

- Windwalker (1980) as Windwalker

- Staying On (1980 TV movie) as Colonel Tusker Smalley

- Arch of Triumph (1980)

- Light Years Away, aka Les Années lumière (1981) as Yoshka Poliakeff

- The Great Muppet Caper (1981) as Aggressive Man in Restaurant (uncredited)

- No Country for Old Men (1981 TV movie)

- Inside the Third Reich (1982 TV movie) as Professor Heinrich Tessnow

- Deadly Game (1982 TV movie) as Gustave Kummer

- The Missionary (1982) as Lord Henry Ames

- Gandhi (1982) as Judge R.S. Broomfield

- Sword of the Valiant (1984) as The King

- Dust (1985) as Le père

- God Rot Tunbridge Wells! (1985) as Georg Frederich Handel

- Memory of the Camps (1985 documentary) as Narrator

- Time After Time (1986) as Brigadier

- Foreign Body (1986) as Dr Stirrup

- Christmas Eve (1986 TV movie) as Maitland

- Hand in Glove (1987 TV movie) as Vicar

- White Mischief (1988) as Jack Soames

- The Unholy (1988) as Father Silva

- The Dawning (1988) as Grandfather

Television credits

- George Washington (1984 miniseries) as Lord Fairfax

- Shaka Zulu (1986–1989) as Lord Charles Somerset (final appearance)

- Peter the Great (1986 TV series) as Sir Isaac Newton

See also

References

- ↑ Pettigrew Trevor Howard: A Personal Biography, London: Peter Owen, 2001, p. 26

- ↑ Pettigrew Trevor Howard: A Personal Biography, London: Peter Owen, 2001, p. 26 and p. 245

- ↑ Profile, filmreference.com; accessed 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Pettigrew Trevor Howard: A Personal Biography, London: Peter Owen, 2001, p. 26

- ↑ See http://www.freebmd.org where his birth is recorded as Trevor W Howard-Smith

- ↑ "World news Howard: the epitome of British stoicism". The Canberra Times. 62, (19, 088). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 9 January 1988. p. 4. Retrieved 1 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Popular star Trevor Howard hides behind beard". The Australian Women's Weekly. 14 (13). 7 September 1946. p. 36. Retrieved 1 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "BFI Screenonline: Howard, Trevor (1916-1988) Biography". www.screenonline.org.uk.

- ↑ "Trevor Howard - Theatricalia". theatricalia.com.

- ↑ Arditti, Michael (10 July 2016). "Theatre reviews: French Without Tears and No Villain".

- ↑ "Trevor Howard details". The Guardian. 3 March 2008.

- ↑ "Production of The Recruiting Officer - Theatricalia". theatricalia.com.

- ↑ "Trevor Howard".

- ↑ "Brief Encounter (1945) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- ↑ 'Bing's Lucky Number: Pa Crosby Dons 4th B.O. Crown', The Washington Post (1923–1954) [Washington, D.C] 03 Jan 1948: 12.

- ↑ Staff, Variety (15 December 2001). "Trevor Howard: A Personal Biography".

- ↑ Drazin, In Search of the Third Man (1999), p. 65

- ↑ "Actor's safety clause". The Sun (2461). New South Wales, Australia. 18 June 1950. p. 46. Retrieved 1 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Hope tops list for popularity". The Mail. Adelaide. 30 December 1950. p. 5 Supplement: Sunday Magazine. Retrieved 19 April 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Vivien Leigh Actress of the Year". Townsville Daily Bulletin. Qld. 29 December 1951. p. 1. Retrieved 27 April 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "COMEDIAN TOPS FILM POLL". The Sunday Herald. Sydney. 28 December 1952. p. 4. Retrieved 27 April 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "The Cockleshell Heroes (1956) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- ↑ "Ibsens "HEDDA GABLER"". The Australian Women's Weekly. 30 (19). 10 October 1962. p. 4 (Television). Retrieved 1 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "AUSTRALIAN FILM FOR THE ACTOR WITH "THE LIVED-IN FACE"?". The Australian Women's Weekly. 42 (52). 28 May 1975. p. 15. Retrieved 1 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Million-dollar movie planned". The Canberra Times. 50, (14, 311). 26 February 1976. p. 16. Retrieved 1 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Terence Pettigrew Trevor Howard: A Personal Biography, London: Peter Owen, 2001, p. 149

- ↑ "The Passionate Lives of Trevor Howard". Ottawa Citizen. 17 February 1961.

- ↑ "No Sir! Stars who refused honors". CNN. 21 December 2003. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ↑ Pettigrew Trevor Howard: A Personal Biography, London: Peter Owen, 2001, p. 245

Sources

- Drazin, Charles (1999). In Search of the Third Man. Methuen. ISBN 0413739309.

- Knight, Vivienne (1986). Trevor Howard: A Gentleman and a Player. Muller, Blond & White. ISBN 978-0584111361.

- Munn, Michael (June 1989). Trevor Howard: The Man and his Films. Robson Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0860515395.

- Pettigrew, Terence (2001). Trevor Howard: A Personal Biography. Peter Owen. ISBN 978-0720611243.