Cherkesogai

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 50,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Armavir, Maykop | |

| Languages | |

| Armenian, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Armenian Apostolic Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Armenians in Russia |

| Part of a series on |

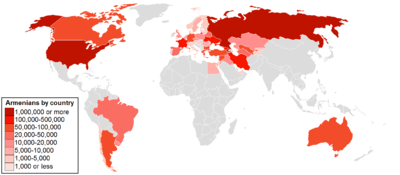

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

|

Architecture · Art Cuisine · Dance · Dress Literature · Music · History |

| By country or region |

|

Armenia · Artsakh See also Nagorno-Karabakh Armenian diaspora Russia · France · India United States · Iran · Georgia Azerbaijan · Argentina · Brazil Lebanon · Syria · Ukraine Poland · Canada · Australia Turkey · Greece · Cyprus Egypt · Singapore |

| Subgroups |

| Hamshenis · Cherkesogai · Armeno-Tats · Lom people · Hayhurum |

| Religion |

|

Armenian Apostolic · Armenian Catholic Evangelical · Brotherhood · |

| Languages and dialects |

| Armenian: Eastern · Western |

| Persecution |

|

Genocide · Hamidian massacres Adana massacre · Anti-Armenianism Hidden Armenians |

|

Armenia Portal |

Cherkesogai (Russian: Черкесогаи) or Circassian Armenians (Armenian: չերքեզահայեր[1] cherk'ezahayer; Russian: черкесские армяне; Circassian: Адыгэ-ермэлы), sometimes referred to as Ermeli (Circassian: Ермэлы), Mountainous Armenians (Russian: горские армяне) or Transkuban Armenians (Russian: закубанские армяне),[2] are ethnic Armenians who have inhabited Russia's Krasnodar Krai and Republic of Adyghea since the end of 15th century and spoke the Adyghe language (currently, most of them speak Russian as their first language), apart from other Armenians living in the region. They reside mostly in the cities of Armavir and Maykop. The total number of Cherkosogai is about 50,000 people (2008 estimate). According to the Russian 2002 Census, 230 Armenians speak Lowland Adyghe and 222 speak Kabardian Adyghe natively.[3]

Notable Cherkesogai include the first Soviet millionaire Artyom Mikhailovich Tarasov, Prix Goncourt-winning writer Henri Troyat (né Lev Aslanovich Tarasov),[4] merchant Nikita Pavlovich Bogarsukov and ballerina Olga Aslanovna Tarasova.[5]

History

Since the early Medieval period, many Armenians have lived as diaspora, due to foreign invasions of Armenia, national and religious persecution, genocide and wars. The formation of the present-day Armenian diaspora in the North Caucasus took place during the 17th and 18th centuries, although the first Hemshin Armenians arrived during the 8th century.[6]

The migrations of Armenians to the Kuban took place in a series of waves. The first took place from the late 1780s to the 1860s, when around 3,000 Armenians came to the region from the Russian towns of Astrakhan, Kizlyar and Mozdok, as well as around 300 Persian Turkish Armenians. During this period, the first Armenian settlements in the Kuban were founded, including Armavir, founded in 1839, considered to be the first. Armenian communities were also established in larger towns such as Novorossiysk, Anapa and Ekaterinodar.[7]

The second wave of migrants came during the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, when around 30,000 mostly Turkish Hemshin Armenians arrived in the region, along with a few from Persia and Transcaucasia. During this period two different types of migrants can be identified: those who came for economic reasons who were attracted by Russian government and those who were forced to leave due to the oppression and genocide by the Ottoman government. The peak of migration activity was reached at the end of the 1870s as a result of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), in the 1890s when pogroms took place against Armenians in Turkey and Baku and from 1915 to 1920 when mass persecution of the Armenian population took place in Turkey.[7]

The third wave of migration took place during the 1950s, when most Armenians settled in Anapsky District, mainly in the settlement of Gaikodzor. These were migrants from Georgia, so-called Akhalkalaki Armenians, named after the town of Akhalkalaki in southern Georgia, and comprised less than 300 people.[7]

The fourth wave took place in the 1970s mainly from two regions: those who came from Azerbaijan, so-called Karabakh Armenians, and those from Central Asia, such as Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kirghizia. They primarily came to Krasnodar Krai for economic reasons and numbered from 5,000 to 7,000 people. From the end of the 1980s to the mid-1990s, more migrants (approximately 300,000) resettled in the Kuban region as a result of the ethnic conflicts across the Soviet Union, mainly from conflict areas such as Azerbaijan, Armenia and Fergana Valley (Uzbekistan and Kirghizia). After these conflicts, there were also migrants who came as a result of poor economic conditions in the newly formed republics, from Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan and republics of Central Asia.[8]

Notable Cherkesogai

- Artyom Mikhailovich Tarasov (born 1950), the first Soviet millionaire

- Henri Troyat (né Lev Aslanovich Tarasov; 1911–2007), Prix Goncourt-winning writer and historian, member of the Académie française

- Nikita Pavlovich Bogarsukov (1834–1913), philanthropist, merchant and diplomat

- Olga Aslanovna Tarasova (1902–1982), ballerina

References

- ↑ Arakelyan, Hranush (1980). "Չերքեզահայերի էթնիկ ինքնագիտակցության հարցի շուրջ [On the self-identity of Circassian Armenians]" (in Armenian). Yerevan: Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Armenian National Academy of Sciences.

- ↑ (in Russian) Л.В. Бурыкина. Черкесогаи Северо-Западного Кавказа в XIX в.

- ↑ 2002 All-Russia Population Census: Language (except Russian) population of the most numerous nationalities (with a population of 400 thousand people or more) Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Galstyan, Ripsime. "Памяти писателя Анри Труайя – предтечи "Майрика"" Pamyati pisatelnya Anri Truajya – predtechi "Majrika" [Memory of the Writer Henri Troyat – Leading "Mayrig"]. Armmuseum.ru (in Russian). Moscow: Armenian Museum of Moscow and Culture of Nations. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017.

Род Тарасовых происходил из черкесогаев. [The Tarasov family originated from the Cherkesogai.]

- ↑ Zatikyan, Magdalina (1 September 2015). "Американский потомок черкесских армян" [Americans of Cherkesogai origin] (in Russian).

- ↑ Ulrike (2014-04-15). Ethnic Belonging, Gender, and Cultural Practices: Youth Identities in Contemporary Russia. Columbia University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9783838261522.

- 1 2 3 Ulrike (2014-04-15). Ethnic Belonging, Gender, and Cultural Practices: Youth Identities in Contemporary Russia. Columbia University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9783838261522.

- ↑ Ulrike (2014-04-15). Ethnic Belonging, Gender, and Cultural Practices: Youth Identities in Contemporary Russia. Columbia University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9783838261522.