Dharmachakra

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

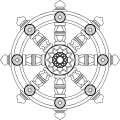

The dharmachakra (which is also known as the wheel of dharma) is one of the Ashtamangala[1] of Indian religions such as Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. It has represented the Buddhist dharma, Gautama Buddha's teaching and walking of the path to Nirvana, since the time of early Buddhism.[2][note 1] It is also connected to the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path.

Etymology

The Sanskrit noun dharma is a derivation from the root dhṛ, which has a meaning of "to hold, maintain, keep",[note 2] and takes a meaning of "what is established or firm", and hence "law". It is derived from the Vedic Sanskrit n-stem dharman- with the meaning "bearer, supporter" in the historical Vedic religion conceived of as an aspect of Ṛta.[4]

History

The wheel is also the main attribute of Vishnu, the Vedic god of preservation.[5] Madhavan and Parpola note Chakra sign appears frequently in Indus Valley civilization, on several seals.[6] Notably, in a sequence of ten signs on the Dholavira signboard, four are the chakra.[7]

Symbol

Common Dharmachakra symbols consist of either 8 or 24 spokes.

Unicode Symbol: ☸ (U+2638: Wheel Of Dharma)

Usage

Hindu usages

According to the Puranas of Hinduism, only 24 Rishis or Sages managed the whole power of the Gayatri Mantra. The 24 letters of the Gayatri Mantra depict those 24 Rishis. Those Rishis represent all the Rishis of the Himalayas, of which the first was Maharshi Vishvamitra and the last was Rishi Yajnavalkya, the author of Yājñavalkya Smṛti which is a Hindu text of the Dharmaśāstra tradition.

The Buddha described the 24 qualities of ideal Buddhist followers, represented by the 24 spokes of the Ashoka Chakra which represent 24 qualities of a Santani:

- Anurāga (Love)

- Parākrama (Courage)

- Dhairya (Patience)

- Śānti (Peace/charity)[8]

- Mahānubhāvatva (Magnanimity)

- Praśastatva (Goodness)

- Śraddāna (Faith)

- Apīḍana (Gentleness)

- Niḥsaṃga (Selflessness)

- Ātmniyantranā (Self-Control)

- Ātmāhavana (Self Sacrifice)

- Satyavāditā (Truthfulness)

- Dhārmikatva (Righteousness)

- Nyāyā (Justice)

- Ānṛśaṃsya (Mercy)

- Chāya (Gracefulness)

- Amānitā (Humility)

- Prabhubhakti (Loyalty)

- Karuṇāveditā (Sympathy)

- Ādhyātmikajñāna (Spiritual Knowledge)

- Mahopekṣā (Forgiveness)

- Akalkatā (Honesty)

- Anāditva (Eternity)

- Apekṣā (Hope)

Also an integral part of the emblem is the motto inscribed below the abacus in Devanagari script: Satyameva Jayate (English: Truth Alone Triumphs).[9] This is a quote from the Mundaka Upanishad,[10] the concluding part of the sacred Hindu Vedas. In the Bhagavad Gita too, verses 14, 15 and 16, of Chapter 3 speaks about the revolving wheel thus: "From food, the beings are born; from rain, food is produced; rain proceeds from sacrifice (yagnya); yagnya arises out of action; know that from Brahma, action proceeds; Brahma is born of Brahman, the eternal Paramatman. The one who does not follow the wheel thus revolving, leads a sinful, vain life, rejoicing in the senses."[11]

Buddhist usages

.svg.png)

The Dharmachakra is one of the ashtamangala of Buddhism.[12][note 3] It is one of the oldest known Buddhist symbols found in Indian art, appearing with the first surviving post-Indus Valley Civilization Indian iconography in the time of the Buddhist king Ashoka.[2][2][note 1]

The Buddha is said to have set the dhammacakka in motion when he delivered his first sermon,[13] which is described in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta. The wheel itself depicts ideas about the cycle of saṃsāra and furthermore the Noble Eightfold Path.

Buddhism adopted the wheel as the main symbol of the chakravartin "wheel-turner", the ideal king[13] or "universal monarch",[5][13] symbolising the ability to cut through all obstacles and illusions.[5]

According to Harrison, the symbolism of "the wheel of the law" and the order of Nature is also visible in the Tibetan prayer wheels. The moving wheels symbolize the movement of cosmic order (ṛta).[14]

The image, having been found in antiquity is referred to as Rimbo (Treasure Ring) is an accepted symbol used in Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism, along with the Swastika.

Beyond the Buddhism religion

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, first Vice President of India has stated that the Ashoka Chakra of India represents the Dharmachakra.[15]

- In the Vishnu Purana and Bhagavata Purana, two kings named Jadabharata of the Hindu solar and lunar dynasties respectively are referred to as "Chakravartins".[16]

- Jagdish Chandra Jain referred to this icon in Kalinga.[17] In Jainism, the Dharmachakra is worshipped as a symbol of the dharma.

- Other "chakras" appear in other Indian traditions, e.g. Vishnu's Sudarśanacakra, a wheel-shaped weapon.

- The former Flag of Sikkim featured a version of the dharmachakra.

- Thai people also use a yellow flag with a red dhammacakka as their Buddhist flag.

- The emblem of Mongolia includes a dharmachakra together with some other Buddhist attributes such as the padma, cintamani, a blue khata and the Soyombo symbol.

- The dharmachakra is also the insignia for Buddhist chaplains in the United States Armed Forces.

- In non-Buddhist cultural contexts, an eight-spoked dharmachakra resembles a traditional ship's wheel. As a nautical emblem, this image is a common sailor tattoo.

- In the Unicode computer standard, the dharmachakra is called the "Wheel of Dharma" and found in the eight-spoked form. It is represented as U+2638 (☸).

The Emblem of Mongolia includes the dharmachakra, a cintamani, a padma, blue khata and the Soyombo symbol

The Emblem of Mongolia includes the dharmachakra, a cintamani, a padma, blue khata and the Soyombo symbol The Emblem of Sri Lanka, featuring a blue dharmachakra as the crest

The Emblem of Sri Lanka, featuring a blue dharmachakra as the crest

.svg.png) The flag of the former Kingdom of Sikkim featured a version of the Dharmachakra

The flag of the former Kingdom of Sikkim featured a version of the Dharmachakra.svg.png) The dhammacakka flag, the symbol of Buddhism in Thailand

The dhammacakka flag, the symbol of Buddhism in Thailand The seal of Thammasat University in Thailand consisting of a Constitution on phan with a twelve-spoked dhammacakkka

The seal of Thammasat University in Thailand consisting of a Constitution on phan with a twelve-spoked dhammacakkka The insignia for Buddhist chaplains in the United States Armed Forces.

The insignia for Buddhist chaplains in the United States Armed Forces. Wheel in Jain Symbol of Ahimsa represents dharmachakra

Wheel in Jain Symbol of Ahimsa represents dharmachakra The Flag of the Romani people also contains a 16-spoke red chakra in the centre, representing the itinerant tradition of the Romani people.

The Flag of the Romani people also contains a 16-spoke red chakra in the centre, representing the itinerant tradition of the Romani people. USVA headstone emblem 2

USVA headstone emblem 2

Falun Dafa

In Falun Gong or Falun Dafa, the Fǎlún (法轮) is described as “an intelligent, rotating entity composed of high-energy matter.” Practitioners of Falun Gong cultivate this Law Wheel, which rotates constantly in the lower abdomen, the same focal point described as Lower Dāntián.

Notes

- 1 2 Grünwedel e.a.:"The wheel (dharmachakra) as already mentioned, was adopted by Buddha's disciples as the symbol of his doctrine, and combined with other symbols—a trident placed above it, etc.—stands for him on the sculptures of the Asoka period."[2]

- ↑ Monier Williams, A Sanskrit Dictionary (1899): "to hold, bear (also: bring forth), carry, maintain, preserve, keep, possess, have, use, employ, practise, undergo"[3]

- ↑ Goetz: "dharmachakra, symbol of the Buddhist faith".[12]

References

- ↑ "Buddhist Symbols". Ancient-symbols.com. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Grünwedel 1901, p. 67.

- ↑ Monier Willams

- ↑ Day 1982, p. 42-45.

- 1 2 3 Beer 2003, p. 14.

- ↑ The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives By Jane McIntosh. Page :377

- ↑ The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives By Jane McIntosh. Page :377

- ↑ "What is Shanti? - Definition from Yogapedia". Yogapedia.com. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ Kamal Dey v. Union of India and State of West Bengal (Calcutta High Court 2011-07-14). Text

- ↑ "Rajya Sabha Parliamentary Standing Committee On Home Affairs: 116th Report on The State Emblem Of India (Prohibition Of Improper Use) Bill, 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2013.

- ↑ "THE BHAGAVAD-GITA" (PDF). Vivekananda.net. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- 1 2 Goetz 1964, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 Pal 1986, p. 42.

- ↑ Harrison & 2010 (1912), p. 526.

- 1 2 "The national flag code" (PDF). Mahapolice.gov.in. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ↑ Titze, Kurt; Bruhn, Klaus (22 June 1998). "Jainism: A Pictorial Guide to the Religion of Non-violence". Motilal Banarsidass Publ. Retrieved 22 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, p. 314, by John Cort, Oxford University

Sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel and Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From The Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University Press

- Beer, Robert (2003), The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols, Serindia Publications, Inc., ISBN 9781932476033

- Day, Terence P. (1982), The Conception of Punishment in Early Indian Literature, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, ISBN 0-919812-15-5

- Goetz, Hermann (1964), The art of India: five thousand years of Indian art., Crown

- Grünwedel, Albert; Gibson, Agnes C.; Burgess, James (1901), Buddhist art in India, Bernard Quaritch

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (2010) [1912], Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion, Cambridge University Press

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2007), Hinduism. In: Joseph Kitagawa, "The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture". Digital printing 2007, Routledge

- Inden, Ronald (1998), Ritual, Authority, And Cycle Time in Hindu Kingship. In: JF Richards, ed., "Kingship and Authority in South Asia", New Delhi: Oxford University Press

- Mallory, J.P. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5

- Nath, Vijay (March–April 2001), "From 'Brahmanism' to 'Hinduism': Negotiating the Myth of the Great Tradition", Social Scientist: 19–50, doi:10.2307/3518337, JSTOR 3518337

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1986), Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700, University of California Press

- Queen, Christopher S.; King, Sallie B. (1996), Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist liberation movements in Asia., SUNY Press

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Yan, Xiaojing (2009), The confluence of East and West in Nestorian Arts in China. In: Dietmar W. Winkler, Li Tang (eds.), Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia, LIT Verlag Münster

Further reading

- Dorothy C. Donath (1971). Buddhism for the West: Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna; a comprehensive review of Buddhist history, philosophy, and teachings from the time of the Buddha to the present day. Julian Press. ISBN 0-07-017533-0.

External links

- Buddhist Wheel Symbol (Dharmachakra)