Arab identity

Arab identity is the objective or subjective state of perceiving oneself as an Arab and as relating to being Arab. It relies on a common culture, a traditional lineage, the common land in history, shared experiences including underlying conflicts and confrontations. These commonalities are regional and tribal. Arab identity is defined independently of religious identity, and pre-dates the spread of Islam, with historically attested Arab Christian tribes and Arab Jewish tribes. Arabs are a diverse group in terms of religious affiliations and practices. Most Arabs are Muslim, with a minority adhering to other faiths, largely Christianity, but also Druze and Baha'i.[1][2]

Arab identity can also be seen through a lens of local or regional identity. Throughout Arab history, there have been three major national trends in the Arab world. Pan-Arabism rejects states' existing sovereignty as artificial creations and calls for full Arab unity.

History

The Arabs are first mentioned in the mid-ninth century BCE as a people living in eastern and southern Syria, and the north of the Arabian Peninsula.[3]

The Arabs appear to have been under the vassalage of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BCE), and then the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BCE), Persian Achaemenid Empire (539–332 BCE), Greek Macedonian/Seleucid Empire and Parthian Empire. Arab tribes, most notably the Ghassanids and Lakhmids begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan from the mid 3rd century CE onwards, during the mid to later stages of the Roman Empire and Sasanian Empire.

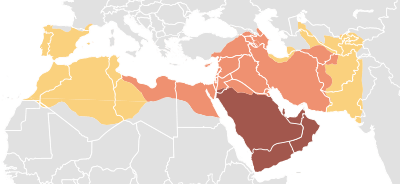

The relation of ʿarab and ʾaʿrāb is complicated further by the notion of "lost Arabs" al-ʿArab al-ba'ida mentioned in the Qur'an as punished for their disbelief. All contemporary Arabs were considered as descended from two ancestors, Qahtan and Adnan. During the early Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries, the Arabs forged the Rashidun and then Umayyad Caliphate, and later the Abbasid Caliphate, whose borders touched southern France in the west, China in the east, Anatolia in the north, and the Sudan in the south. This was one of the largest land empires in history.

Ideology

Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people. In its contemporary conception, it is the belief that the Arab people are a people united by language, culture, ethnicity, history, geography and interests, and that one Arab state will assemble the Arabs within its borders from the ocean to the Gulf. The Arabs believed that they were an old nation. It showed Arab pride in Arabic poetry. In the era of Islam, nationalism was manifested by the feeling of the Arabs as a distinct nation within Islam. In the modern era, this idea was embodied by ideologies such as Nasserism and Ba'athism, which were the most common in the Arab world, especially in the mid-twentieth century until the end of the seventies, characterized by the establishment of the United Arab Republic between Egypt and Syria and witnessed many other attempts of unity. Arab nationalism gained a new popular range as a result of the Arab Spring and the emergence of an Arab popular trend calling for an Arab unity led by the people, not the authoritarian regimes that installed the wave of nationalism without accomplishing anything in this direction.

Arab socialism

Arab socialism is a political ideology based on the confusion between Arab nationalism and socialism. Arab socialism differs from the socialist ideas prevalent in the Arab world.[4] For many, including Michel Aflaq, Arab socialism was a natural step towards the consolidation of Arab unity and freedoms, since the socialist system of ownership and development alone can overcome the remnants of colonialism in the Arab world.[5][6]

Unity

Pan-Arabism

Pan-Arabism is an ideology espousing the unification of the countries of North Africa and West Asia from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea, referred to as the Arab world.[7] The idea is based on the integration of some or all of the Arab countries into a single political and economic framework that removes the borders between the Arab states and establishes a strong economic, human and military state.[8] Arab unity is an idea that the Arab nationalists believe as a solution to the backwardness, occupation and oppression that the Arab citizen lives in all the countries of this country extending from the ocean to the Gulf.[9]

Arab League

The Arab League, formally the League of Arab States is a regional organization of Arab countries in and around North Africa, the Horn of Africa and Arabia. It was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945 with six members: Kingdom of Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, Transjordan (renamed Jordan in 1949), Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Syria.[10][11] Its charter provides for coordination among member states in economic matters, including trade relations, communications, cultural relations, nationalities, travel documents and permits, social relations and health.[12]

Definition

A member of a Semitic people, inhabiting much of the Middle East and North Africa.[13][14][15][16] The ties that bind Arabs are ethnic, linguistic, cultural, historical, identical, nationalist, geographical and political.[17] They have their own customs, language, architecture, art, literature, music, dance, media, cuisine, dress, society, sports and mythology.[18]

According to Arab-Islamic-Jewish traditions, Ishmael was father of the Arabs, to be the ancestor of the Ishmaelites they are the descendants of Ishmael, the elder son of Abraham and the descendants of the 12 sons/princes of Ishmael.[19]

| “ | Those who belong to the Arab ethnic group, the Arab people or the Arab nation, speak a form of Arabic and consider it their "natural" language; regard the history and cultural characteristics of the Arabs as their inheritance; assert an Arab identity or consciousness.—Maxime Rodinson | ” |

| “ | By "Arab" I mean whoever describes himself thus … there, where he is - in his history, his memory, the place where he lives, dies and survives. There, where he is - that is to say, in the experience of a life which is both tolerable and intolerable for him.—Abdelkebir Khatibi | ” |

| “ | Arabs: name given to the ancient and present-day inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula and often applied to the peoples closely allied to them in ancestry, language, religion, and culture. Presently more than 200 million Arabs are living mainly in 21 countries; they constitute the overwhelming majority of the population in Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, and the nations of North Africa. The Arabic language is the main symbol of cultural unity among these people, but the religion of Islam provides another common bond for the majority of Arabs.—Encarta Encyclopedia | ” |

Homeland

The Arab world, formally the Arab homeland,[20][21][22] also known as the Arab nation or the Arab states,[23] currently consists of the 22 Arab countries: Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates and Yemen, occupy an area stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. Arab world has a combined population of around 422 million inhabitants.[24]

Categories

Arab identity can be described as consisting of many interconnected parts:

Racial identity

Arabs belong to the Semitic branch of the Caucasian race, mostly Mediterranean race.[25][26][27][28] The Arabid race[29] is a term for a morphological subtype of the Caucasoid race, as used in physical anthropology.[30] Some recent genetic studies have found (by analysis of the DNA of Semitic-speaking peoples), Y-chromosomal links between modern Semitic-speaking peoples of the Middle East like Arabs, Hebrews, Mandaeans, Samaritans, and Assyrians.

Medieval Arab genealogists divided Arabs into three groups:

- "Ancient Arabs" tribes that had vanished or been destroyed.

- "Pure Arabs" descending from Qahtan who was a descendant of Ishmael.

- The "Arabized Arabs" descending from Ishmael the elder son of Abraham.

The Arabs refuse to classify and called them as "white" they identify themselves as "Arab".[31][32][33] When it comes to Arabs it seems this important point is often lost, as see more and more attempts to position them as “white.”[34] According to the US Census Bureau, they are considered to be “white” and the Arabs still embrace and defend that status today.[35][36]

Ethnic identity

Ethnic identity is another factor in Arab identity, who identify, linguistically, identically, culturally, societally, ancestrally, historically, politically, nationally and genealogically as "Arab".

In the modern era, it is defined who is an Arab based on these criteria:

- Genealogical: someone who can trace his or her ancestry to the Arab tribes, from the Arabian Desert, Syrian Desert and neighboring areas.[37]

- Ancestral: belonging to Arab people, inherited from grandparents, or denoting an ancestor or ancestors.

- Self-concept: a person who defines himself as "Arab", belongs to the Arab nation.

- Identical: someone being as an Arab.

- Linguistic: someone whose first language, and by extension cultural expression, is Arabic.[38][39]

- Cultural: someone who belongs to Arab culture relating to the ideas, customs, and social behavior of a society.

- Political: someone his country is a member of the League of Arab States and who is in sympathy with the aspirations of the Arab peoples. (i.e. Somalis and Djiboutians).

- Societal: while self-reliance, individuality, and responsibility are taught by Arabic parents to their children, family loyalty is the greatest lesson taught in Arab families.

- National: one who is a national of an Arab state or characteristic of Arab nationalism.

National identity

National identity is one's identity or sense of belonging to one state or to one nation.[40] It is the sense of a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, language and politics.[41] Arab nationalism is a nationalist ideology celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language and literature of the Arabs, calling for rejuvenation and political union in the Arab world. The premise of Arab nationalism is the need for an ethnic, political, cultural and historical unity among the Arab peoples of the Arab countries.[42] The main objective of Arab nationalism was to achieve the independence of Western influence of all Arab countries.[43] Arab political strategies with the nation in order to determine the struggle of the Arab nation with the state system (nation-state) and the struggle of the Arab nation for unity.[44] The concepts of new nationalism and old nationalism are used in analysis to expose the conflict between nationalism, national ethnic nationalism, and new national political nationalism. These two aspects of national conflicts highlight the crisis known as the Arab Spring, which affects the Arab world today.[45] Suppressing the political struggle to assert the identity of the new civil state is said to clash with the original ethnic identity.[46]

Religious identity

Until about the fourth century, almost all Arabs practised polytheistic religions.[47] Although significant Jewish and Christian minorities developed, polytheism remained the dominant belief system in pre-Islamic, most Arabs followed a pagan religion with a number of deities, including Hubal,[48] Wadd, Allāt,[49] Manat, and Uzza. A few individuals, the hanifs, had apparently rejected polytheism in favor of monotheism unaffiliated with any particular religion. Different theories have been proposed regarding the role of Allah in Meccan religion.[50][51][52][53] Today the majority of Arabs are Muslims, identities are often seen as inseparable. The "Verse of brotherhood" is the tenth verse of the Quranic chapter "Al-Hujurat", is about brotherhood of believers with each other.[54][55][56] However, there were divergent currents in Arabism - one religious and secular one - throughout Arab history. After the collapse of the Ottoman Islamic caliphate in the 20th century, Arab nationalism emerged on the religious front. These two trends have continued to overcome each other to this day. Now, religious fundamentalism offers an alternative to secular nationalism. There are also different religious denominations within Islam and are often valuable to religion as a whole, leading to sectarian conflict and conflict. In fact, the social and psychological distances between Sunni and Shia Muslims may be greater than the perceived distance between different religions. Because of this, Islam can be seen both as a unification and as a force of division in Arab identity.[57]

Cultural Identity

Arab cultural identity is characterized by complete uniformity. Arab cultural space are historically so tightly interwoven.[58] Arab cultural identity has been assessed through four measures that measure the basic characteristics of Arab culture: religiosity, grouping, belief in gender hierarchy and attitudes toward sexual behavior. The results indicate the predominance of the professional strategies that Arab social workers have learned in their training in social work, while indicating the willingness of social workers to benefit from established strategies in their culture and society, either separately or in combination with the professional.[59] There are different aspects of Arab identity, whether ethnic, religious, national, linguistic or cultural - of different fields and analytical angles.[60][61]

| “ | The family is still at the heart of traditional Arabic letters that the fact that the family is a basic unit of social organization in the traditional Arab contemporary society may explain why it continues to exercise a significant influence on the formation of identity. At the heart of social and economic activities, this institution is still very coherent. Exercise the early and most lasting influence on the person's affiliations.—Halim Barakat | ” |

Linguistic identity

For some Arabs, beyond language, race, religion, tribe or region. Arabic; hence, can be considered as a common factor among all Arabs. Since the Arabic language also exceeds the country's border, the Arabic language helps to create a sense of Arab nationalism.[62] According to the Iraqi world exclusive Cece, "it must be people who speak one language one heart and one soul, so should form one nation and thus one country." There are two sides to the coin, argumentative. While the Arabic language as one language can be a unifying factor, the language is often not unique at all. Accents vary from region to region, there are wide differences between written and spoken versions, many countries host bilingual citizens, many Arabs are illiterate. This leads us to examine other identifying aspects of Arabic identity.[63] Arabic, a Semitic language from the Afroasiatic language family. Modern Standard Arabic serves as the standardized and literary variety of Arabic used in writing, as well as in most formal speech, although it is not used in daily speech by the overwhelming majority of Arabs. Most Arabs who are functional in Modern Standard Arabic acquire it through education and use it solely for writing and formal settings.

Political identity

Arab political identity characterized by restraint, tolerance, compassion, hospitality, generosity, tolerance restraint, proper conduct, equality and unanimity. Arab countries to redefine politics are linked to the fact that the political culture behind the Arabs has been overrun for centuries by successive political.[64][65] The vast majority of the citizens of the Arab countries view themselves and are seen by outsiders as "Arabs". Their sense of the Arab nation is based on their common denominators: language, culture, ethnicity, social and political experiences, economic interests and the collective memory of their place and role in history.[66]

The relative importance of these factors is estimated differently by different groups and frequently disputed. Some combine aspects of each definition, as done by Palestinian Habib Hassan Touma:[67]

| “ | "One who is a national of an Arab state, has command of the Arabic language, and possesses a fundamental knowledge of Arab tradition, that is, of the manners, customs, and political and social systems of the culture. | ” |

The Arab League, a regional organization of countries intended to encompass the Arab world, defines an Arab as:

| “ | An Arab is a person whose language is Arabic, who lives in an Arab country, and who is in sympathy with the aspirations of the Arab peoples.[68] | ” |

See also

References

- ↑ Ori Stendel. The Arabs in Palestine. Sussex Academic Press. p. 45. ISBN 1898723249. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mohammad Hassan Khalil. Between Heaven and Hell: Islam, Salvation, and the Fate of Others. Oxford University Press. p. 297. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Myers, E. A. (2010-02-11). The Ituraeans and the Roman Near East: Reassessing the Sources. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139484817.

- ↑ TORREY, GORDON H.; DEVLIN, JOHN F. (1965). "Arab Socialism". Journal of International Affairs. 19 (1): 47–62. doi:10.2307/24363337. JSTOR 24363337.

- ↑ "No Arab Bolivars: As region implodes, Arab socialism fizzles out". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- ↑ "Coping with the Legacy of Arab Socialism". Cato Institute. 2014-08-25. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- ↑ "Pan-Arabism Is Not Dead | Opinion | The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- ↑ "Pan-Arabism - Oxford Reference". doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100303333.

- ↑ "Pan-Arabism | ideology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- ↑ "Arab League". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Sly, Liz (12 November 2011). "Syria suspended from Arab League". Washington Post.

- ↑ "Profile: Arab League". BBC News. 2017-08-24. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- ↑ Naylor, Chris (2015). Postcards from the Middle East: How our family fell in love with the Arab world. Lion Books. ISBN 9780745956503.

- ↑ "Arab | Definition of Arab in US English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English.

- ↑ BOARD, V&S EDITORIAL (2015). ENGLISH - ENGLISH DICTIONARY (in German). V&S Publishers. ISBN 9789350574195.

- ↑ "member of a semitic people spread throughout middle east, n africa etc. Crossword Clue, Crossword Solver". www.wordplays.com.

- ↑

- Kjeilen, Tore. "Arabs – LookLex Encyclopaedia". looklex.com.

- "Who is an Arab?". al-bab.com. 3

- War of Visions: Conflict of Identities in the Sudan. p 405. By Francis Mading Deng

- ↑

- "Culture and Tradition in the Arab Countries". www.habiba.org.

- "Arabic Culture & Traditions – Online Resources | Pimsleur Approach™". www.pimsleurapproach.com.

- El-Shamy, Hasan M. (1995). Folk traditions of the Arab world : a guide to motif classification (1. [Dr.]. ed.). Bloomington u.a.: Indiana Univ. Press. ISBN 0253352223.

- ↑

- Both Judaism and Islam see him as the ancestor of Arab peoples. Jones, Lindsay (2005). Encyclopedia of religion. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 9780028657400.

- Ishmael is recognized by Muslims as the ancestor of several prominent Arab tribes and being the forefather of Muhammad. A–Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism, Wheeler, Ishmael Muslims also believe that Muhammad was the descendant of Ishmael that would establish a great nation, as promised by God in the Old Testament.*Genesis 17:20Zeep, Ira G. (2000). A Muslim primer: beginner's guide to Islam, Volume 2. University of Arkansas Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-55728-595-9.

- Ishmael was considered the ancestor of the Northern Arabs and Muhammad was linked to him through the lineage of the patriarch Adnan. Ishmael may also have been the ancestor of the Southern Arabs through his descendant Qahtan.

- "Zayd ibn Amr" was another Pre-Islamic figure who refused idolatry and preached monotheism, claiming it was the original belief of their [Arabs] father Ishmael. *The Beginning and the End by Ibn Kathir – Vol. 3, p. 323 The History by Ibn Khaldun, Vol, 2, p. 4

- The tribes of Central West Arabia called themselves the "people of Abraham and the offspring of Ishmael". The Signs of Prophethood, Section 18, page 215."Signs of Prophethood in the Noble Life of Prophet Muhammad (part 1 of 2): Prophet Muhammad's Early Life – The Religion of Islam". www.islamreligion.com.

- Gibb, Hamilton A.R. and Kramers, J.H. (1965) Shorter Encyclopedia of Islam. Ithaca:Cornell University Press. pp. 191–98

- Maalouf, Tony. Arabs in the Shadow of Israel: The Unfolding of God's Prophetic Plan for Ishmael's Line. Kregel Academic. ISBN 9780825493638.

- Urbain, Olivier (2008). Music and Conflict Transformation: Harmonies and Dissonances in Geopolitics. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781845115289.

- ↑ Khan, Zafarul-Islam. "The Arab World – an Arab perspective". www.milligazette.com.

- ↑ Phillips, Christopher (12 November 2012). "Everyday Arab Identity: The Daily Reproduction of the Arab World". Routledge.

- ↑ Mellor, Noha; Rinnawi, Khalil; Dajani, Nabil; Ayish, Muhammad I. (20 May 2013). "Arab Media: Globalization and Emerging Media Industries". John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ "Majority and Minorities in the Arab World: The Lack of a Unifying Narrative". Jerusalem Center For Public Affairs.

- ↑ "World Arabic Language Day". UNESCO. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ The Leisure Hour: An Illustrated Magazine for Home Reading. W. Stevens, Printer. 1852.

- ↑ High Points in the Work of the High Schools of New York City. Board of Education, New York City. 1941.

- ↑ Twomey, David (2012). Labor and Employment Law: Text & Cases. Cengage Learning. ISBN 1133188281.

- ↑ Boosahda, Elizabeth (2010). Arab-American Faces and Voices: The Origins of an Immigrant Community. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292783133.

- ↑ John R. Baker Race. — New York and London: Oxford University Press, 1974. — P. 625. ISBN 978-0-936396-04-0

- ↑ "The Mediterranean race in Arabia". Theapricity.com. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Zebib, Laura (13 February 2017). "Stop Calling Me White. I Am Arab". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Beydoun, Khaled A. "Are Arabs white?". www.aljazeera.com.

- ↑ "Am I white? – the classification of Arabs in America has a messy history and it still matters". The Tempest. 11 August 2017.

- ↑ "Comment: Why Arabs are not 'white'". Topics.

- ↑ "Are Arab Americans White? Maybe Not, according to US Census – All About America". VOA.

- ↑ "White House wants to add new racial category for Middle Eastern people". USA TODAY.

- ↑ (Regueiro et al.) 2006; found agreement by (Battaglia et al.) 2008

- ↑ Jankowski, James. "Egypt and Early Arab Nationalism" in Rashid Kakhlidi, ed., Origins of Arab Nationalism, pp. 244–245

- ↑ Quoted in Dawisha, Adeed. Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press. 2003, ISBN 0-691-12272-5, p. 99

- ↑ Tajfel, H; Turner, J.C (1986). "The Social Identity Theory of Inter-group Behavior". Psychology of Intergroup Relations.

- ↑ "Definition of National Identity in English". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Dawisha, Adeed (2003-01-01). "Requiem for Arab Nationalism". Middle East Quarterly.

- ↑ "Arab Nationalism: Mistaken Identity | Martin Kramer on the Middle East". martinkramer.org. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ "Rise of Arab nationalism - The Ottoman Empire | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of Arab Nationalism". users.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ "A short history of Arab Nationalism | www.socialism.com". www.socialism.com. Retrieved 2017-03-27.

- ↑ Robert G. Hoyland (11 September 2002). Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-134-64634-0.

- ↑ "Is Hubal The Same As Allah?". Islamic-awareness.org. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ Dictionary of Ancient Deities. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514504-6.

- ↑ Jonathan Porter Berkey (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600-1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3.

- ↑ Neal Robinson (5 November 2013). Islam: A Concise Introduction. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-136-81773-1.

- ↑ Francis E. Peters (1994). Muhammad and the Origins of Islam. SUNY Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7914-1875-8.

- ↑ Daniel C. Peterson (26 February 2007). Muhammad, Prophet of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8028-0754-0.

- ↑ Brotherhood in the Quran and Sunnah | Faith in Allah الإيمان بالله

- ↑ The Bonds of Brotherhood

- ↑ "Al-Hujurat chapter".

- ↑ García-Arenal, Mercedes (2009-01-01). "The Religious Identity of the Arabic Language and the Affair of the Lead Books of the Sacromonte of Granada". Arabica. 56 (6): 495–528. JSTOR 25651684.

- ↑ "Cultural Identity in the Islamic World | MR Online". MR Online. 17 May 2009.

- ↑ Sabry, Tarik (2012). Arab Cultural Studies: Mapping the Field. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781848855595.

- ↑ Sabry, edited by Tarik (2012). Arab cultural studies : mapping the field. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1848855591.

- ↑ Anishchenkova, Valerie (2014). Autobiographical Identities in Contemporary Arab Culture. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748643417.

- ↑ "Arab Origins: Identity, History and Islam - British Academy Blog". British Academy Blog. 2015-07-20. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ D., Phillips, Christopher, Ph. (2013-01-01). Everyday Arab identity : the daily reproduction of the Arab world. Routledge. ISBN 9780415684880. OCLC 841752039.

- ↑ "Arabs at the Crossroads: Political Identity and Nationalism | Middle East Policy Council". www.mepc.org.

- ↑ Hoyt, Paul D. (1998). "Legitimacy, Identity, and Political Development in the Arab World". Mershon International Studies Review: 173–176. doi:10.2307/254461. JSTOR 254461.

- ↑ Eid, Paul (2007). Being Arab: Ethnic and Religious Identity Building among Second Generation Youth in Montreal. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 9780773577350.

- ↑ 1996, p.xviii

- ↑ Dwight Fletcher Reynolds, Arab folklore: a handbook, (Greenwood Press: 2007), p.1.