Buraq

Al-Burāq (Arabic: البُراق al-Burāq or /ælˈbɔːræk/ "lightning") is a steed in Islamic mythology, a creature from the heavens that transported the prophets. Most notably Buraq carried the Islamic prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Jerusalem and back during the Isra and Mi'raj or "Night Journey",[1] as recounted in hadith literature.

Etymology

The Encyclopaedia of Islam, referring to Al-Damiri's writings, considers Buraq to be a derivative of Arabic: برق barq "lightning".[2] According to Encyclopædia Iranica, "Boraq" is the Arabized form of "Middle Persian *barāg or *bārag, 'a riding beast, mount' (New Pers. bāra)".[3]

Description

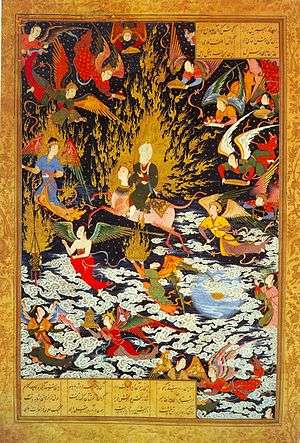

Near East and Persian art almost always portrays Buraq with a human face, a portrayal that found its way into Indian and Persian Islamic art. Yet no hadiths or early Islamic references allude to it having a humanoid face. This may have been originated from a misrepresentation or translation from Arabic to Persian of texts and stories describing the winged steed as a "beautiful faced creature".

An excerpt from a translation of Sahih al-Bukhari describes Buraq:

Then a white animal which was smaller than a mule and bigger than a donkey was brought to me ... The animal's step (was so wide that it) reached the farthest point within the reach of the animal's sight.

Another describes the Buraq in greater detail:

Then he [Gabriel] brought the Buraq, handsome-faced and bridled, a tall, white beast, bigger than the donkey but smaller than the mule. He could place his hooves at the farthest boundary of his gaze. He had long ears. Whenever he faced a mountain his hind legs would extend, and whenever he went downhill his front legs would extend. He had two wings on his thighs which lent strength to his legs.

He bucked when Muhammad came to mount him. The angel Jibril (Gabriel) put his hand on his mane and said: "Are you not ashamed, O Buraq? By Allah, no-one has ridden you in all creation more dear to Allah than he is." Hearing this he was so ashamed that he sweated until he became soaked, and he stood still so that the Prophet mounted him.[5]

In the earlier descriptions there is no agreement as to the sex of the Buraq. It is typically male, yet Ibn Sa'd has Gabriel address the creature as a female, and it was often rendered by painters with a woman's head.[6] The fact that "al-Buraq" is a mare is also noted in the book The Dome of the Rock,[7] in the chapter "The Open Court", and in the title-page vignette of Georg Ebers's Palestine in Picture and Word.

Journey to the Seventh Heaven

According to Islam, the Night Journey took place ten years after Muhammad became a prophet, during the 7th century. Muhammad had been in his home city of Mecca, at his cousin's home (the house of Fakhitah bint Abi Talib). Afterwards, Muhammad went to the Great Mosque of Mecca. While he was resting at the Kaaba, the angel Jibril appeared to him, followed by Buraq. Muhammad mounted Buraq, and in the company of Jibril, they traveled to the "farthest mosque".

The location of this mosque was not explicitly stated but is generally accepted to mean al-Aqsa Mosque at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. At this location, he dismounted from Buraq, prayed, and mounted Buraq, who took him to the various heavens, to meet first the earlier prophets and then God. God instructed Muhammad to tell his followers that they were to offer prayers fifty times a day. At the urging of Musa (Moses), Muhammad returns to God and eventually reduces it to ten times, and then five times a day as this was the destiny of Muhammad and his people. Buraq then transported Muhammad back to Mecca.[8]

Abraham

According to ibn Ishaq, Buraq transported Ibrahim (Abraham) when he visited his wife, Hagar, and son, Ismail (Ishmael). That tradition states that Abraham lived with one wife, Sarah, in Syria, but Buraq would transport him in the morning to Mecca to see his family there and take him back in the evening to his wife in Syria.[9]

Western Wall

Various scholars and writers, such as ibn al-Faqih, ibn Abd Rabbih, and Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi, have suggested places where Buraq was supposedly tethered in stories, mostly locations near the southwest corner of the Haram.[10] However, for several centuries the preferred location has been the al-Buraq Mosque, just inside the wall at the south end of the Western Wall plaza.[10] The mosque sits above an ancient passageway that once came out through the long-sealed Barclay's Gate whose huge lintel remains visible below the Maghrebi gate.[10] Because of the proximity to the Western Wall, the area next to the wall has been associated with Buraq at least since the 19th century.[11]

When a British Jew asked the Egyptian authorities in 1840 for permission to re-pave the ground in front of the Western Wall, the governor of Syria wrote:

It is evident from the copy of the record of the deliberations of the Consultative Council in Jerusalem that the place the Jews asked for permission to pave adjoins the wall of the Haram al-Sharif and also the spot where the Buraq was tethered, and is included in the endowment charter of Abu Madyan, may God bless his memory; that the Jews never carried out any repairs in that place in the past. ... Therefore the Jews must not be enabled to pave the place.[11]

Carl Sandreczki, charged with compiling a list of place names for Charles William Wilson's Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem in 1865, reported that the street leading to the Western Wall, including the part alongside the wall, belonged to the Hosh (court/enclosure) of al Burâk, "not Obrâk, nor Obrat".[12] In 1866, the Prussian Consul and Orientalist Georg Rosen wrote: "The Arabs call Obrâk the entire length of the wall at the wailing place of the Jews, southwards down to the house of Abu Su'ud and northwards up to the substructure of the Mechkemeh [Shariah court]. Obrâk is not, as was formerly claimed, a corruption of the word Ibri (Hebrews), but simply the neo-Arabic pronunciation of Bōrâk, ... which, whilst (Muhammad) was at prayer at the holy rock, is said to have been tethered by him inside the wall location mentioned above."[13]

The name Hosh al Buraq appeared on the maps of Wilson's 1865 survey, its revised editions in 1876 and 1900, and other maps in the early 20th century.[14] In 1922, the official Pro-Jerusalem Council specified it as a street name.[15]

The association of the Western Wall area with Buraq has played an important role in disputes over the holy places since the British mandate.[16]

Cultural impact

- In Turkey, Burak is a common male name.

- Two airlines have been named after Buraq: Buraq Air of Libya, and the former Bouraq Indonesia Airlines of Indonesia (closed in 2006).

- "el-Borak" is a pirate in Rafael Sabatini's novel The Sea Hawk; "El Borak" is a character in short stories by Robert E. Howard. Both are named for their speed and reflexes.

- Pakistan's NESCOM Burraq was named after Buraq.

- Aceh, Indonesia, has adopted the image of Buraq rampant on the proposed official seal of the province's government.[17]

- Iran's Boragh APC is named after it.

- A Malaysian petrol company is named Buraq Oil.[18]

- Al Buraq name of Ship owned by AMPTC

See also

- Pegasus

- Haizum

- Rakhsh

- Merkabah mysticism

- Cherub

- Tetramorph

- Elijah's chariot of fire

- Lamassu (similar winged bull creature)

- Vahana

References

- ↑ Vuckovic, Brooke Olson (2004). Heavenly Journeys, Earthly Concerns. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 9781135885243. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ Gruber, Christane J., “al-Burāq”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Edited by: Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Consulted online on 14 April 2018 <https://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_24366>

- ↑ Hadith v. as Influenced by Iranian Ideas and Practices at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:58:227

- ↑ Muhammad al-Alawi al-Maliki, al-Anwar al Bahiyya min Isra wa l-Mi'raj Khayr al-Bariyyah

- ↑ T.W. Arnold (1965). Painting in Islam (PDF). p. 118.

- ↑ Grabar, Oleg (October 30, 2006). The Dome of the Rock. Belknap Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0674023130.

- ↑ Sullivan, Leah. "Jerusalem: The Three Religions of the Template Mount" (PDF). stanford.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ↑ Firestone, Reuven (1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. SUNY Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7914-0331-0. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Elad, Amikam (1995). Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage. BRILL. p. 101-2. ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- 1 2 F. E. Peters (1985). Jerusalem. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 541–542. . Arabic text in A. L. Tibawi (1978). The Islamic Pious Foundations in Jerusalem. London: The Islamic Cultural Centre. Appendix III.

- ↑ Carl Sandrecki (1865). Account of a Survey of the City of Jerusalem made in order to ascertain the names of streets etc. Day IV. reproduced in Captain Charles W. Wilson R.E. (1865). Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem (Facsimile ed.). Ariel Publishing House (published 1980). Appendix.

- ↑ G. Rosen (1866). Das Haram von Jerusalem und der Tempelplatz des Moria (in German). Gotha. pp. 9–10.

Die ganze Mauerstrecke am Klageplatz der Juden bis südlich an die Wohnung des Abu Su'ud und nördlich an die Substructionen der Mechkemeh wird von den Arabern Obrâk genannt, nicht, wie früher behauptet worden, eine Corruption des Wortes Ibri (Hebräer), sondern einfach die neu-arabische Aussprache von Bōrâk, [dem Namen des geflügelten Wunderrosses,] welches [den Muhammed vor seiner Auffahrt durch die sieben Himmel nach Jerusalem trug] und von ihm während seines Gebetes am heiligen Felsen im Innern der angegebenen Mauerstelle angebunden worden sein soll.

- ↑ Captain Charles W. Wilson R.E. (1865). Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem (Facsimile ed.). Ariel Publishing House (published 1980). maps. Wilson 1876 Archived 9 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.; Wilson 1900 Archived 16 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine.; August Kümmel 1904 Archived 16 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine.; Karl Baedeker 1912; George Adam Smith 1915.

- ↑ Council of the Pro-Jerusalem Society (1924). C. R. Ashby, ed. Jerusalem 1920-1922. London: John Murray. p. 27.

- ↑ Halkin, Hillel (12 January 2001). ""Western Wall" or "Wailing Wall"?". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ↑ Singa dan Burak menghiasi lambang Aceh dalam rancangan Qanun (Lion and Buraq decorate the coat of arms of Aceh in the Draft Regulation) Atjeh Post, 19 November 2012.

- ↑ "About Company". Buraq Oil. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buraq. |