Tiraz

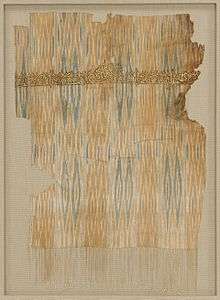

Tiraz (Arabic طراز) are medieval Islamic garments/armbands with inscription embroidered on them. They were given to officials as robes of honor to high-ranking officials who show loyalty to the Islamic empire. They were inscribed with the ruling caliph's names, and were embroidered with threads of precious metal and decorated with complex patterns. Tiraz were a symbol of power, their productions and exports were strictly regulated, and was overseen by a government-appointed official.

Etymology

The word tiraz is a Persian word for "embroidery". The word tiraz can be used to refer to the textiles themselves, or to the band of calligraphic inscription on them, or to the factories which produced the textiles (known as the dar al-tiraz).[1]

Tiraz is also known as taraziden in Persian.

Islamic dress code

The notion of dress code in the Islamic world evolved early at the beginning of the expansion of the new empire. As the empire expanded across the region, cultural divisions were established, each with its own dress code. The Arabs, a minority in their own empire, distinguished themselves by establishing a rule which would establish differentiation (ghiyar) to maintain identity. Regulation of this kind was first ascribed by caliph Umar (634-644) in the so-called Pact of Umar, a list of rights and restrictions on non-Muslims which would granted security of their persons, families, and possessions. As the vestimentary system evolved, so to the application of the rule. Requirements were also applied to the Arab military; for example, Arab warriors set up in the eastern provinces were forbidden to wear the Persian kaftan and leggings.[2]

By the end of the Umayyad Caliphate in mid 8th-century, dress code law had become less strict.[2] Arabs living in as far as Khorasan had become assimilated with the local culture, including the way they dress.[3] The trend of moving away from the stricter vestimentary system also occurred in the high-rank officials, even at early times. It has been recorded that Arab rulers of the Umayyad already wore Persian-style coats, with pantaloons and qalansuwa turbans. High-rank officials of the Umayyad also adopted the custom of wearing luxurious regal garments of silk, satin, and brocade; a tradition in the royal courts of the Byzantine and the Sasanian. Following the tradition of Byzantine and Persian rulers, the Umayyads also established state factories to produce the tiraz. Tiraz garments indicate to whom the wearer was loyal to by indications of an inscription (e.g. the name of the ruling caliph), similar with the embellishment of the caliph's name on coins.[2]

Tiraz bands were presented to loyal subjects in a formal ceremony. Ceremony of the bestowing of the tiraz, known as the khil'a ("robe of honor") ceremony, can be traced as far as the time of Prophet Muhammad. Khil'a ceremony gained importance under of Fatimid caliph al-Mu'izz; in which the ceremony was held in high regard and was attended by the ruling caliph as well as the master of the tiraz factories.[4] High-quality gold tiraz bands, embroidered onto silk robes, were bestowed to deserving vizier and other high-ranking officials; the quality of tiraz reflects the influence (and wealth) of the recipient.[1][5]

As the custom of bestowing tiraz gained high regards, public studios (‘amma) began imitating the custom of bestowing tiraz by producing their own tiraz for public use. In Fatimid Egypt, people who could afford the ‘amma tiraz would perform their own "khil'a" ceremony on family and friends, as documented in the documents of Cairo Geniza and relics found in Cairo. These "public tiraz" were considered family treasures and passed down as heirlooms. Tiraz was also given as gifts. A sovereign in Andalusia was recorded to present a tiraz to another sovereign in North Africa.[2][5]

Tiraz was also used in funerary rituals. In Fatimid Egyptian funeral, a tiraz band was wrapped around the head of the deceased with their eyes covered with it. The blessings imbued into the tiraz from the earlier khil'a ceremony, as well as the fact that there was the inscription of Quranic verses, would make the tiraz especially suited for funeral ceremonies.[1]

By the 13th-century, tiraz production started to decline. With the weakening of the Islamic power, nobles began to sold their tiraz on the open market. Some tiraz served as a form of investment where they were traded and sold. Despite the decline, tiraz continued to be produced up into the 14th-century[1]

Design and production

There were two types of tiraz factories: the official caliph (khassa, meaning "private" or "exclusive") and public (‘amma, meaning "public"). There are no differences in design between the tiraz produced in the caliph or in the public factory because both are designed with the same name of the ruling caliph, and both have the same quality.[1] The ‘amma factories produce tiraz for commercial use. The more official khassa factories were more like administrative departments, controlling and enrolling craftsmen who worked in production factories located away from the center, normally in places known for the production of a particular fabric.[4]

Tiraz garments vary in their material and design, depending on the time of their production, where they are produced and for whom they are produced. Fabrics e.g. linen, wool, cotton or mulham (mixture of silk wrap and cotton) were used for tiraz production. The Yemeni tiraz has the characteristic striped lozenge design of green, yellow, and brown; this is produced through resist-dyeing and ikat technique. In Egypt, tiraz were left undyed but embroidered with red or black thread. Most early tiraz was decorated with colorful motifs of medallions or animals, but with no inscription. Discovery of tiraz across the periods shows a gradual transition of Sasanian, Coptic and Byzantine style. During the Fatimid period in 11th- and 12th-century Egypt, the trend of tiraz design shows revival of these styles.[1]

Inscriptions were usually found in tiraz from the later period. The inscriptions can be made of gold thread or painted. The inscriptions were written in Arabic. The kufic script (and its variation, the floriated kufic) were found in earlier tiraz. In later period, the naskh or thuluth script became common. The inscriptions were designed in calligraphy to form artistic rhythmic pattern.[1] The inscription may contain the name of the ruling caliph, the date and the place of manufacture, phrases taken from the Quran or from many invocations to Allah.[4] The khassikiya (royal bodyguard) of the mamluk Sultanate wore a highly decorative tiraz woven with gold or silver metallic thread.[6] In Fatimid Egypt, silk tiraz woven with golden inscription were reserved for the vizier and other high-ranking officials, while general public wore linen.[1]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tiraz. |

References

Cited works

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400829941.

- Ekhtiar, Maryam; Cohen, Julia (2015). "Tiraz: Inscribed Textiles from the Early Islamic Period". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Fossier, Robert (1986). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521266444.

- Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135455965.