Anamorphosis

Anamorphosis is a distorted projection or perspective requiring the viewer to use special devices or occupy a specific vantage point (or both) to reconstitute the image. The word "anamorphosis" is derived from the Greek prefix ana‑, meaning "back" or "again", and the word morphe, meaning "shape" or "form". An optical anamorphism is the visualization of a mathematical operation called an affine transformation.[1] The process of extreme anamorphosis has been used by artists to disguise caricatures, erotic and scatological scenes, and other furtive images from a casual viewer, while revealing an undistorted image to the knowledgeable spectator.

Types of projection

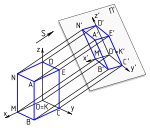

There are two main types of anamorphosis: perspective (oblique) and mirror (catoptric). More-complex anamorphoses can be devised using distorted lenses, mirrors, or other optical transformations.

Examples of perspectival anamorphosis date to the early Renaissance (fifteenth century). Examples of mirror anamorphosis were first seen in the late Renaissance (sixteenth century).

With mirror anamorphosis, a conical or cylindrical mirror is placed on the drawing or painting to transform a flat distorted image into an apparently undistorted picture that can be viewed from many angles. The deformed image is painted on a plane surface surrounding the mirror. By looking into the mirror, a viewer can see the image undeformed.

With Channel anamorphosis or turning pictures two different images are on different sides of a corrugated carrier. A straight frontal view shows an unclear mix of the images, while each image can be viewed correctly from a certain angle.

History

Leonardo's Eye (Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1485) is the earliest known definitive example of perspective anamorphosis in modern times. The prehistoric cave paintings at Lascaux may also use this technique, because the oblique angles of the cave would otherwise result in distorted figures from a viewer's perspective.

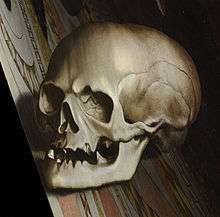

Hans Holbein the Younger is well known for incorporating an oblique anamorphic transformation into his painting The Ambassadors. In this artwork, a distorted shape lies diagonally across the bottom of the frame. Viewing this from an acute angle transforms it into the plastic image of a human skull, a symbolic memento mori. During the seventeenth century, Baroque trompe l'oeil murals often used anamorphism to combine actual architectural elements with illusory painted elements. When a visitor views the art work from a specific location, the architecture blends with the decorative painting. The dome and vault of the Church of St. Ignazio in Rome, painted by Andrea Pozzo, represented the pinnacle of illusion. Due to neighboring monks complaining about blocked light, Pozzo was commissioned to paint the ceiling to look like the inside of a dome, instead of building a real dome. As the ceiling is flat, there is only one spot where the illusion is perfect and a dome looks undistorted.

Mirror anamorphosis emerged early in the 17th century in Italy and China. It remains uncertain whether Jesuit missionaries imported or exported the technique.[2]

Anamorphosis could be used to conceal images for privacy or personal safety. A secret portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie (now held at the West Highland Museum, Scotland) is painted in a distorted manner on a tray and can only be recognized when a polished cylinder is placed in the correct position. To possess such an image would have been seen as treason in the aftermath of the 1746 Battle of Culloden.[3]

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, anamorphic images had come to be used more as children's games than fine art. In the twentieth century, some artists wanted to renew the technique of anamorphosis. Marcel Duchamp was interested in anamorphosis, and some of his installations are "visual paraphrases" of anamorphoses (see The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even / The Large Glass). Jan Dibbets conceptual works, the so-called "perspective corrections" are examples of "linear" anamorphoses. In the late twentieth century, mirror anamorphosis was revived as children's toys and games.

Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí used extreme foreshortening and anamorphism in his paintings and works, and had a glass floor installed in a room next to his studio to enable radical perspective studies from above and below.[4] His Dalí Theatre and Museum in Figueres, Spain features a 3-dimensional anamorphic living-room installation with custom furniture that looks like the face of Mae West when seen from a certain viewpoint.[5]:156[6]:28

In the work of contemporary artists

Beginning in 1967, Dutch artist Jan Dibbets based an entire series of photographic work titled Perspective Corrections on the distortion of reality through perspective anamorphosis. The Swedish artist Hans Hamngren produced and exhibited many examples of mirror anamorphosis in the 1960s and 1970s. Shigeo Fukuda, a Japanese artist, designed both types of anamorphosis in the 1970s and 1980s. Patrick Hughes, Fujio Watanabe, William Kentridge, René Luckhardt, István Orosz, Felice Varini, Ed Ruscha, Matthew Ngui, Kelly Houle, Nigel Williams, and Judy Grace are artists creating anamorphic images.

Un carré pour un square is an anamorphosis made by the French artist Jean-Max Albert in 1988. From the specific vantage point, the perspective of a square is seen, inscribed in Place Fréhel, Paris, France. The design is formed by a set of lines of narrow plates of Carrara marble imbricated in the walls of the surrounding buildings and in the vestiges of a former construction site. A low wall and a pillar in masonry were created to shape the other side of the design.[7][8][9] In another example by the same artist, the specific vantage point is indicated by one of the Observation Sculptures[10] set in Paris, Parc de la Villette. In this work, the anamorphosis appears as a reflection of a bronze construction[11] This reflection discreetly shows the inclusion of a circle in a square in a triangle, in reference to the concept plan of the park by the architect Bernard Tschumi.[12][13] Notably, Reflet Anamorphose allows, from the specific vantage point, to observe simultaneously the design and its anamorphosis.

From 2006, artist Jonty Hurwitz[14] pioneered the area of anamorphic sculpture using mathematical techniques and 3D printing. His work rose to fame in early 2013 when it was blogged by art critic Christopher Jobson on his Webby Award-winning site Colossal,[15] receiving 30 million views online.[16] The Savoy Hotel engaged Hurwitz as artist in residence to produce an anamorphic work for their River Room, for a restaurant called Kaspars.[17]

The Dutch artist Leon Keer made an optical illusion painting with a life-size mirror cylinder during the 3-D street painting event FringeMK, in 2010.

Another form of anamorphic art is often called "Slant Art". Examples are the sidewalk chalk drawings of Kurt Wenner and Julian Beever, where the chalked image, the pavement, and the architectural surroundings all become part of an illusion. Art of this style can be produced by taking a photograph of an object or setting at a sharp oblique angle, then putting a grid over the photograph. Another elongated grid is placed on the sidewalk based on a specific perspective, and visual elements of one are transcribed into the other, one grid square at a time.

In November, 2011, an article published on the website of the Smithsonian magazine questioned if an anamorphic garden work by French artist François Abélanet featured in front of Paris city hall, the Hôtel de Ville entitled, "Qui croire?" ("Who to believe?") was really the "World’s Greatest New Artwork?",[18] citing an online video of it.[19]

Hurwitz Singularity, anamorphic sculpture using perspective

Hurwitz Singularity, anamorphic sculpture using perspective Anamorphic frog sculpture by Jonty Hurwitz

Anamorphic frog sculpture by Jonty Hurwitz Vera Bugatti: cylindrical mirror anamorphosis with portrait

Vera Bugatti: cylindrical mirror anamorphosis with portrait.jpg) Anamorphic street art by Manfred Stader

Anamorphic street art by Manfred Stader Three views of a conical anamorphosis by Dimitri Parant

Three views of a conical anamorphosis by Dimitri Parant- Pyramidal anamorphosis

- Cylindrical anamorphosis

Jean-Max Albert, Reflet anamorphose, Bronze, Parc de la Villette.1985

Jean-Max Albert, Reflet anamorphose, Bronze, Parc de la Villette.1985 Jean-Max Albert, Un carré pour un square, from the specific vantage point, Place Fréhel, Paris.1988

Jean-Max Albert, Un carré pour un square, from the specific vantage point, Place Fréhel, Paris.1988.jpg) Anamorphic mosaic art in a West Bromwich bus station

Anamorphic mosaic art in a West Bromwich bus station

Impossible objects

In the twentieth century, artists began to play with perspective by drawing "impossible objects". These objects included stairs that always ascend, or cubes where the back meets the front. Such works were popularized by the artist M. C. Escher and the mathematician Roger Penrose. Although referred to as "impossible objects", such objects as the Necker Cube and the Penrose triangle can be sculpted in 3-D by using anamorphic illusion. When viewed at a certain angle, such sculptures appear as the so-called impossible objects.

Practical uses

Cinemascope, Panavision, Technirama, and other widescreen formats use anamorphosis to project a wider image from a narrower film frame. The IMAX company uses even more extreme anamorphic transformations to project moving images from a flat film frame onto the inside of a hemispheric dome, in its "Omnimax" or "IMAX Dome" process.

The technique of anamorphic projection can be seen quite commonly on text written at a very flat angle on roadways, such as "Bus Lane" or "Children Crossing", to make it easily read by drivers who otherwise would have difficulty reading obliquely as the vehicle approaches the text; when the vehicle is nearly above the text, its true abnormally elongated shape can be seen. Similarly, in many sporting stadiums, especially in Rugby football in Australia, it is used to promote company brands which are painted onto the playing surface; from the television camera angle, the writing appear as signs standing vertically within the field of play.

Much writing on shop windows is in principle anamorphic, as it was written mirror-reversed on the inside of the window glass.

Warning text on roadway is predistorted for oblique viewing by motorists

Warning text on roadway is predistorted for oblique viewing by motorists Mirror anamorphosis on the lower front of an ambulance, so the writing appears right way round in rear view mirrors of vehicles ahead of it in traffic

Mirror anamorphosis on the lower front of an ambulance, so the writing appears right way round in rear view mirrors of vehicles ahead of it in traffic Anamorphic writing on helmets. The helmet's visor goes up between layers of the helmet shell. On the resulting very sloping helmet forehead, the writing is anamorphic, so an onlooker sees it horizontally, undistorted.

Anamorphic writing on helmets. The helmet's visor goes up between layers of the helmet shell. On the resulting very sloping helmet forehead, the writing is anamorphic, so an onlooker sees it horizontally, undistorted.

Popular culture

Since 1993, Myrna Hoffman’s company, OOZ & OZ, has been producing mirror anamorphosis art kits and activities for children, such as the "Morph-O-Scopes" kit.[20] Hoffman's kits have earned more than two dozen national toy awards.

Anamorphic portraits were produced of members of the group Steeleye Span for the sleeve of their album All Around My Hat in 1975 by John O'Connor, a friend of one of them. The album packaging included a lyric sheet with holes punched in the side through which to view the portraits in their correct perspective.

Rick Wakeman's 1976 album No Earthly Connection featured front and back cover photographs that are mirror anamorphoses. The original vinyl release included a mirrored Mylar sheet which could be curled into a cylinder for viewing the images.[21]

In the 2007 detective film Anamorph, the plot line revolves around the solution of gruesome anamorphically distorted images.

Some 0.5 liter Sprite bottles in Europe were imprinted with what appeared to be an extra "bar code". When the bottle was tilted towards the mouth while drinking, the bar code resolved into writing, due to the oblique perspective.

The 2009 video game Batman: Arkham Asylum has a series of riddles posed by the classic Batman antagonist The Riddler, the solution of which is based on perspective anamorphosis.[22]

In 2013, Honda released a commercial which incorporated a series of illusions based on anamorphosis.[23]

See also

- Adelbert Ames Jr. Ames Demonstrations

- Anamorphic format, a widescreen film technique

- Anamorphic widescreen, a widescreen video encoding concept

- Arthur Mole

- Image warping

- Mad Fold-in

- Perspective control

- Panomorph

Artists

References

- ↑ Sánchez-Reyes, Javier; Chacón, Jesús M. (August 1, 2016). "Anamorphic Free-Form Deformation". Computer Aided Geometric Design. 46: 30–42. doi:10.1016/j.cagd.2016.06.002. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ↑ Review: Anamorphic Act by Jurgis Baltrušaitis. 1979. JSTOR 3049875.

- ↑ "Now you see me". West Highland Museum. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ Ades, ed. by Dawn (2000). Dalí's optical illusions : [Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, January 21 - March 26, 2000 : Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, April 19 - June 18, 2000 ; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, July 25 - October 1, 2000]. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Univ. Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0300081770.

- ↑ King, Elliott H. (guest curator) (2010). Salvador Dalí : the late work. David A. Brenneman, managing curator ; with contrib. by William Jeffet, Montse Aguer Teixidor, Hank Hine. Atlanta, Ga: High Museum of Art and Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300168280.

- ↑ Pitxot, Antoni; Montse Aguer Teixidor; photography, Jordi Puig; translation, Steve Cedar (2007). The Dalí Theatre-Museum. Sant Lluís, Menorca: Triangle Postals. ISBN 9788484782889.

- ↑ François Lamarre, Jean-Max Albert illusionniste éclectique, L’empreinte 27, décembre 1994

- ↑ Monique Faux, L'art renouvelle la ville, Editions Skira, Paris 1992

- ↑ Space in profile/ L'espace de profil,

- ↑ Jean-Max Albert's observation sculptures Sarah Mc Fadden, The Bulletin 24, Bruxelles, June 16th 1994

- ↑ Bruno Suner, Les sculptures de visées du Parc de la Villette, Urbanisme 215, 1986

- ↑ Jardin-de-la-Treille, wikimapia

- ↑ Las Miras del Jardin de la Parra

- ↑ Art of Jonty Hurwitz

- ↑ Christopher Jobson (January 21, 2013). "The Skewed, Anamorphic Sculptures and Engineered Illusions of Jonty Hurwitz". Colossal.

- ↑ Jonty Hurwitz (February 4, 2013). The paintbrush of mathematics. Youtube.

- ↑ Alice Jones (May 2, 2013). "A homage to Kaspar the friendly cat checks in at the Savoy's new eatery". The Independent.

- ↑ Adams, Henry (Nov 29, 2011), Is a "Garden" the World's Greatest New Artwork?

- ↑ Stevenson, Scott (July 20, 2011), Most Amazing World Illusion! - Magic World

- ↑ "Sports of All Sorts". OOZandOZ.com. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Rick Wakeman official website". rwcc.com. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Batman FAQ". GamerShell.com. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ↑ "This Honda Ad Leaves Me a Little Flat". Slate. 2013-10-26. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

Bibliography

- Andersen, Kirsti (1996) "The mathematical treatment of anamorphoses from Piero della Francesca to Niceron", pp 3 to 28 in History of Mathematics, J.W. Dauben, M. Folkerts, E. Knobloch & H. Wussing editors, ISBN 0-12-204055-4 MR 1388783.

- Baltrusaitis, Jurgis (1984) Anamorphoses ou Thaumaturgus opticus. Flammarion, Paris.

- Behrens, R.R. (2009a). "Adelbert Ames II" entry in Camoupedia: A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage. Dysart IA: Bobolink Books, pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-9713244-6-8.

- Behrens, R.R. (2009b). "Ames Demonstrations in Perception" in E. Bruce Goldstein, ed., Encyclopedia of Perception. Sage Publications, pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8.

- Cole, Alison: Perspective (1992) Dorling Kindersley, London.

- Collins, Daniel L. (1992) Anamorphosis and the Eccentric Observer. Leonardo, Berkeley.

- Damisch, Hubert: L’Origine de la perspective (1987) Flammarion, Paris.

- De Rosa, Agostino; D'Acunto, Giuseppe (2002) La Vertigine dello Sguardo. Tre saggi sulla rappresentazione anamorfica (The Vertigo of Sight. Three Essays on the Anamorphic Representation). Cafoscarina Publishing, Venice. ISBN 9788888613314

- De Rosa, Agostino (Ed), Jean François Nicéron (2012) Prospettiva, catottrica e magia artificiale (Jean François Nicéron. Perspective, catoptric and artificial magic), 2 Vols. with critical editions and translations of J. F. Nicéron's La Perspective curieuse and Thaumaturgus opticus. Marsilio, Venezia.

- Du Breuil, La Pere (1649) La Perspective pratique. Paris.

- Fischer, Sören (2016) "Una vista amirabile": Remarks on the Illusionary Interplay Between Real and Painted Windows in 16th Century Italy, in The Most Noble of the Senses: Anamorphosis, Trompe-L'Oeil, and Other Optical Illusions in Early Modern Art, ed. by Lilian Zirpolo, Ramsey, New Jersey, ISBN 978-0-9972446-1-8, pp. 1–28.

- Foister, Susan, Roz Ashok, Wyld Martin. Holbein's Ambassadors. National Gallery Publications, London.

- Haddock, Nickolas (2013) "Medievalism and Anamorphosis: Curious Perspectives on the Middle Ages," in Medievalism Now, ed. E.L. Risden, Karl Fugelso, and Richard Utz (special issue of The Year's Work in Medievalism, 28).

- Houle, Kelly (2003) Portrait of Escher: Behind the Mirror. M.C. Escher's Legacy. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

- Kircher, Athanasius (1646) Ars Magna lucis et umbrae in decem Libros digesta. Rome.

- Lanners, Edi: Illusionen. VerlagC.J.Bucher GmbH, München und Luzern, 1973.

- Leemann, Fred: Anamorphosen. DuMont Buchverlag, Köln, 1975.

- Leemann, Fred: Hidden Images. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, NewYork, 1976.

- Maignan, Emmanuel (1648) Perspectiva horaria, sive de Horographia gnomonica.... Rome.

- Mastai, M. L. d'Otrange (1975) Illusion in Art. Abaris Books, New York.

- Niceron, Jean-Francois (1638) La Perspective curieuse ou magie artificelle des effets merveilleux. Paris.

- Niceron, Jean-Francois (1646) Thaumaturgus opticus, seu Admiranda optices per radium directum, catoptrices per radium reflectum. Paris.

- North, John (2002) The Ambassadors' Secret. Hamblendon and London, London

- István, Orosz (2000) Artistic Expression of Mirror, Reflection and Perspective. Symmetry.

- – (2002) Portland Press, London.

- István, Orosz (2003) The Mirrors of the Master. Escher Legacy. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

- Quay, Stephen and Timothy (1991) De Artificiali Perspectiva, or Anamorphosis (film)

- Shickman, Allan: "Turning Pictures" in Shakespeare’s England. University of N. Iowa, Cedar Falls Ia. Art Bulletin LIX/March 1, 1977.

- Sakane, Itsuo: A Museum of Fun (The Expanding Perceptual World) The Asahi Shimbun, Tokyo, 1979 (Part I.) 1984 (Part II.)

- Schott, Gaspar (1657) Magia universalis naturae et artis. Würzburg.

- Stillwell, John (1989) Mathematics and Its History, §7.2 Anamorphosis, pp 81,2, Springer ISBN 0-387-96981-0.

- The Arcimboldo Effect (1987) (exhibition catalogue - Palazzo Grassi, Velence) Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri, Bompiani, Milan.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anamorphosis. |

| Look up anamorphosis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |