Salvador Dalí

| The Most Illustrious Salvador Dalí OCIII OIC LH | |

|---|---|

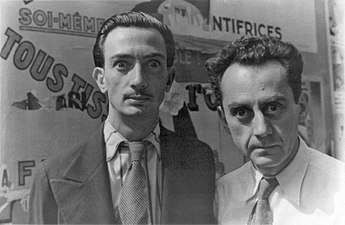

Dalí photographed by Carl Van Vechten on 29 November 1939 | |

| Born |

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech 11 May 1904 Figueres, Catalonia, Spain |

| Died |

23 January 1989 (aged 84) Figueres, Catalonia, Spain |

| Resting place | Crypt at Dalí Theatre and Museum, Figueres |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Education | San Fernando School of Fine Arts, Madrid, Spain |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, photography, sculpture, writing, film, jewelry |

| Notable work | |

| Movement | Cubism, Dada, Surrealism |

| Spouse(s) | |

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1st Marquis of Dalí de Púbol (11 May 1904 – 23 January 1989), known professionally as Salvador Dalí (/ˈdɑːli,

Dalí was a skilled draftsman, best known for the striking and bizarre images in his surrealist work. His painterly skills are often attributed to the influence of Renaissance masters.[3][4] His best-known work, The Persistence of Memory, was completed in August 1931. Dalí's expansive artistic repertoire included film, sculpture, and photography, at times in collaboration with a range of artists in a variety of media.

Dalí attributed his "love of everything that is gilded and excessive, my passion for luxury and my love of oriental clothes"[5] to an "Arab lineage", claiming that his ancestors were descended from the Moors.[6][7]

Dalí was highly imaginative, and also enjoyed indulging in unusual and grandiose behavior. His eccentric manner and attention-grabbing public actions sometimes drew more attention than his artwork, to the dismay of those who held his work in high esteem, and to the irritation of his critics.[8][6]

Biography

Early life

.jpg)

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech was born on 11 May 1904, at 8:45 am GMT,[9] on the first floor of Carrer Monturiol, 20 (presently 6),[10] in the town of Figueres, in the Empordà region, close to the French border in Catalonia, Spain.[11] Dalí's older brother, who had also been named Salvador (born 12 October 1901), had died of gastroenteritis nine months earlier, on 1 August 1903. His father, Salvador Rafael Aniceto Dalí Cusí (1872–1950)[12] was a middle-class lawyer and notary,[13] an anti-clerical atheist and Catalan federalist, whose strict disciplinary approach was tempered by his wife, Felipa Domènech Ferrés (1874–1921),[14] who encouraged her son's artistic endeavors.[15] In the summer of 1912, the family moved to the top floor of Carrer Monturiol 24 (presently 10).[16][17]

When he was five, Dalí was taken to his brother's grave and told by his parents that he was his brother's reincarnation,[18] a concept which he came to believe.[19] Of his brother, Dalí said, "[we] resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections."[20] He "was probably a first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute."[20] Images of his long-dead brother would reappear embedded in his later works, including Portrait of My Dead Brother (1963).

Dalí also had a sister, Anna Maria, who was three years younger.[13] In 1949, she published a book about her brother, Dalí as Seen by His Sister.[21] His childhood friends included future FC Barcelona footballers Sagibarba and Josep Samitier. During holidays at the Catalan resort of Cadaqués, the trio played football (soccer) together.[22]

Dalí attended drawing school. In 1916, he also discovered modern painting on a summer vacation trip to Cadaqués with the family of Ramon Pichot, a local artist who made regular trips to Paris.[13] The next year, Dalí's father organized an exhibition of his charcoal drawings in their family home. He had his first public exhibition at the Municipal Theatre in Figueres in 1919, a site he would return to decades later.

On 6 February 1921, Dalí's mother died of cancer of the uterus.[23] Dalí was 16 years old; he later said his mother's death "was the greatest blow I had experienced in my life. I worshipped her... I could not resign myself to the loss of a being on whom I counted to make invisible the unavoidable blemishes of my soul."[6][24] After her death, Dalí's father married his deceased wife's sister. Dalí did not resent this marriage, because he had great love and respect for his aunt.[13]

Madrid, Barcelona and Paris

In 1922, Dalí moved into the Residencia de Estudiantes (Students' Residence) in Madrid[13] and studied at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. A lean 1.72 metres (5 ft 7 3⁄4 in) tall,[25] Dalí already drew attention as an eccentric and dandy. He had long hair and sideburns, coat, stockings, and knee-breeches in the style of English aesthetes of the late 19th century.

At the Residencia, he became close friends with (among others) Pepín Bello, Luis Buñuel, and Federico García Lorca. The friendship with Lorca had a strong element of mutual passion,[26] but Dalí rejected the poet's sexual advances.[27]

However it was his paintings, in which he experimented with Cubism, that earned him the most attention from his fellow students. His knowledge of Cubist art had come from magazine articles and a catalog given to him by Pichot, since there were no Cubist artists in Madrid at the time.

In 1924, Dalí, still unknown to the public, illustrated a book for the first time. It was a publication of the Catalan poem Les bruixes de Llers ("The Witches of Llers") by his friend and schoolmate, poet Carles Fages de Climent. Dalí also experimented with Dada, which influenced his work throughout his life.[28]

Dalí held his first solo exhibition at Galeries Dalmau in Barcelona, from 14 to 27 November 1925.[29][30] At the time Dalí was not yet immersed in the Surrealist style for which he would later become famous. The exhibition was well received by the public and critics. The following year he exhibited again at Galeries Dalmau, from 31 December 1926 to 14 January 1927, with the support of the art critic Sebastià Gasch.[31][32]

Dalí left the Academy in 1926, shortly before his final exams.[6] His mastery of painting skills at that time was evidenced by his realistic The Basket of Bread, painted in 1926.[33] That same year, he made his first visit to Paris, where he met Pablo Picasso, whom the young Dalí revered.[6] Picasso had already heard favorable reports about Dalí from Joan Miró, a fellow Catalan who introduced him to many Surrealist friends.[6] As he developed his own style over the next few years, Dalí made a number of works strongly influenced by Picasso and Miró.

Some trends in Dalí's work that would continue throughout his life were already evident in the 1920s. Dalí was influenced by many styles of art, ranging from the most academically classic, to the most cutting-edge avant-garde.[34] His classical influences included Raphael, Bronzino, Francisco de Zurbarán, Vermeer and Velázquez.[35] He used both classical and modernist techniques, sometimes in separate works, and sometimes combined. Exhibitions of his works in Barcelona attracted much attention and a mixture of praise and puzzled debate from critics.

Dalí grew a flamboyant moustache, influenced by 17th-century Spanish master painter Diego Velázquez. The moustache became an iconic trademark of his appearance for the rest of his life.

1929 to World War II

.jpeg)

In 1929, Dalí collaborated with surrealist film director Luis Buñuel on the short film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). His main contribution was to help Buñuel write the script for the film. Dalí later claimed to have also played a significant role in the filming of the project, but this is not substantiated by contemporary accounts.[36] Also, in August 1929, Dalí met his lifelong and primary muse and future wife Gala,[37] born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova. She was a Russian immigrant ten years his senior, who at that time was married to surrealist poet Paul Éluard. In the same year, Dalí had important professional exhibitions and officially joined the Surrealist group in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. His work had already been heavily influenced by surrealism for two years. The Surrealists hailed what Dalí called his paranoiac-critical method of accessing the subconscious for greater artistic creativity.[13][15]

Meanwhile, Dalí's relationship with his father was close to rupture. Don Salvador Dalí y Cusi strongly disapproved of his son's romance with Gala, and saw his connection to the Surrealists as a bad influence on his morals. The final straw was when Don Salvador read in a Barcelona newspaper that his son had recently exhibited in Paris a drawing of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Christ, with a provocative inscription: "Sometimes, I spit for fun on my mother's portrait".[6][7]

Outraged, Don Salvador demanded that his son recant publicly. Dalí refused, perhaps out of fear of expulsion from the Surrealist group, and was violently thrown out of his paternal home on 28 December 1929. His father told him that he would be disinherited, and that he should never set foot in Cadaqués again. The following summer, Dalí and Gala rented a small fisherman's cabin in a nearby bay at Port Lligat. He bought the place, and over the years enlarged it by buying the neighbouring fishermen cabins, gradually building his much beloved villa by the sea. Dalí's father would eventually relent and come to accept his son's companion.[38]

In 1931, Dalí painted one of his most famous works, The Persistence of Memory,[39] which introduced a surrealistic image of soft, melting pocket watches. The general interpretation of the work is that the soft watches are a rejection of the assumption that time is rigid or deterministic. This idea is supported by other images in the work, such as the wide expanding landscape, and other limp watches shown being devoured by ants.[40]

Dalí and Gala, having lived together since 1929, were civilly married on 30 January 1934 in Paris.[41] They later remarried in a Church ceremony on 8 August 1958 at Sant Martí Vell.[42] In addition to inspiring many artworks throughout her life, Gala would act as Dalí's business manager, supporting their extravagant lifestyle while adeptly steering clear of insolvency. Gala seemed to tolerate Dalí's dalliances with younger muses, secure in her own position as his primary relationship. Dalí continued to paint her as they both aged, producing sympathetic and adoring images of her. The "tense, complex and ambiguous relationship" lasting over 50 years would later become the subject of an opera, Jo, Dalí (I, Dalí) by Catalan composer Xavier Benguerel.[43]

Dalí was introduced to the United States by art dealer Julien Levy in 1934. The exhibition in New York of Dalí's works, including Persistence of Memory, created an immediate sensation. Social Register listees feted him at a specially organized "Dalí Ball". He showed up wearing a glass case on his chest, which contained a brassiere.[44] In that year, Dalí and Gala also attended a masquerade party in New York, hosted for them by heiress Caresse Crosby, the inventor of the brassiere. For their costumes, they dressed as the Lindbergh baby and his kidnapper. The resulting uproar in the press was so great that Dalí apologized. When he returned to Paris, the Surrealists confronted him about his apology for a surrealist act.[45]

While the majority of the Surrealist artists had become increasingly associated with leftist politics, Dalí maintained an ambiguous position on the subject of the proper relationship between politics and art. Leading surrealist André Breton accused Dalí of defending the "new" and "irrational" in "the Hitler phenomenon", but Dalí quickly rejected this claim, saying, "I am Hitlerian neither in fact nor intention".[46] Dalí insisted that surrealism could exist in an apolitical context and refused to explicitly denounce fascism.[47] Among other factors, this had landed him in trouble with his colleagues. Later in 1934, Dalí was subjected to a "trial", in which he narrowly avoided being expelled from the Surrealist group.[48] To this, Dalí retorted, "The difference between the surrealists and me is, I myself am surrealism" (la différence entre les surréalistes et moi, c'est que moi je suis surréaliste).[49][50]

In 1936, Dalí took part in the London International Surrealist Exhibition. His lecture, titled Fantômes paranoiaques authentiques, was delivered while wearing a deep-sea diving suit and helmet.[51] He had arrived carrying a billiard cue and leading a pair of Russian wolfhounds, and had to have the helmet unscrewed as he gasped for breath. He commented that "I just wanted to show that I was 'plunging deeply' into the human mind."[52] In 1936, Dalí, aged 32, was featured on the cover of Time magazine.[6]

Also in 1936, at the premiere screening of Joseph Cornell's film Rose Hobart at Julien Levy's gallery in New York City, Dalí became famous for another incident. Levy's program of short surrealist films was timed to take place at the same time as the first surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, featuring Dalí's work. Dalí was in the audience at the screening, but halfway through the film, he knocked over the projector in a rage. "My idea for a film is exactly that, and I was going to propose it to someone who would pay to have it made", he said. "I never wrote it down or told anyone, but it is as if he had stolen it". Other versions of Dalí's accusation tend to the more poetic: "He stole it from my subconscious!" or even "He stole my dreams!"[53]

In this period, Dalí's main patron in London was the wealthy Edward James. He had helped Dalí emerge into the art world by purchasing many works and by supporting him financially for two years. They also collaborated on two of the most enduring icons of the Surrealist movement: the Lobster Telephone and the Mae West Lips Sofa.[54]

Meanwhile, Spain was going through a civil war (1936–1939), with many artists taking a side or going into exile.

In 1938, Dalí met Sigmund Freud thanks to Stefan Zweig. Dalí started to sketch Freud's portrait, while the 82-year-old celebrity confided to others that "This boy looks like a fanatic." Dalí was delighted upon hearing later about this comment from his hero.[6]

Later, in September 1938, Salvador Dalí was invited by Gabrielle Coco Chanel to her house "La Pausa" in Roquebrune on the French Riviera. There he painted numerous paintings he later exhibited at Julien Levy Gallery in New York.[55][56] At the end of the 20th century, "La Pausa" was partially replicated at the Dallas Museum of Art to welcome the Reeves collection and part of Chanel's original furniture for the house.[57]

Also in 1938, Dalí unveiled Rainy Taxi, a three-dimensional artwork, consisting of an actual automobile with two mannequin occupants. The piece was first displayed at the Galerie Beaux-Arts in Paris at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, organised by André Breton and Paul Éluard. The Exposition was designed by artist Marcel Duchamp, who also served as host.[58][59][60]

At the 1939 New York World's Fair, Dalí debuted his Dream of Venus surrealist pavilion, located in the Amusements Area of the exposition. It featured bizarre sculptures, statues, and live nude models in "costumes" made of fresh seafood, an event photographed by Horst P. Horst, George Platt Lynes and Murray Korman. Like most attractions in the Amusements Area, an admission fee was charged.[61]

In 1939, André Breton coined the derogatory nickname "Avida Dollars", an anagram for "Salvador Dalí", a phonetic rendering of the French phrase avide à dollars, meaning "eager for dollars".[62] This was a derisive reference to the increasing commercialization of Dalí's work, and the perception that Dalí sought self-aggrandizement through fame and fortune. The Surrealists, many of whom were closely connected to the French Communist Party at the time, expelled him from their movement.[6] Some surrealists henceforth spoke of Dalí in the past tense, as if he were dead.[63] The Surrealist movement and various members thereof (such as Ted Joans) would continue to issue extremely harsh polemics against Dalí until the time of his death, and beyond.

World War II

In 1940, as World War II tore through Europe, Dalí and Gala retreated to the United States, where they lived for eight years splitting their time between New York and Monterey, California.[64] They were able to escape because on June 20, 1940, they were issued visas by Aristides de Sousa Mendes, Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, France. Salvador and Gala Dalí crossed into Portugal and subsequently sailed on the Excambion from Lisbon to New York in August 1940. Dalí’s arrival in New York was one of the catalysts in the development of that city as a world art center in the post-war years.[65] After the move, Dalí returned to the practice of Catholicism. "During this period, Dalí never stopped writing", wrote Robert and Nicolas Descharnes.[66]

Dalí worked prolifically in a variety of media during this period, designing jewelry, clothes, furniture, stage sets for plays and ballet, and retail store display windows. In 1939, while working on a window display for Bonwit Teller, he became so enraged by unauthorized changes to his work that he shoved a decorative bathtub through a plate glass window.[6]

Dali spent the winter of 1940–41 at Hampton Manor, the residence of bra designer and patron of the arts Caresse Crosby, near Bowling Green in Caroline County, Virginia. During his time there, he spent his time on various projects. He was described as a "showman" by residents in the local newspaper.[67]

In 1941, Dalí drafted a film scenario for Jean Gabin called Moontide. In 1942, he published his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. He wrote catalogs for his exhibitions, such as that at the Knoedler Gallery in New York in 1943, in which he attacked some often-used surrealist techniques by proclaiming, "Surrealism will at least have served to give experimental proof that total sterility and attempts at automatizations have gone too far and have led to a totalitarian system. ... Today's laziness and the total lack of technique have reached their paroxysm in the psychological signification of the current use of the college" (collage). He also wrote a novel, published in 1944, about a fashion salon for automobiles. This resulted in a drawing by Edwin Cox in The Miami Herald, depicting Dalí dressing an automobile in an evening gown.[66]

In The Secret Life, Dalí suggested that he had split with Luis Buñuel because the latter was a Communist and an atheist. Buñuel was fired (or resigned) from his position at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), supposedly after Cardinal Spellman of New York went to see Iris Barry, head of the film department at MOMA. Buñuel then went back to Hollywood where he worked in the dubbing department of Warner Brothers from 1942 to 1946. In his 1982 autobiography Mon Dernier soupir (My Last Sigh, 1983), Buñuel wrote that, over the years, he had rejected Dalí's attempts at reconciliation.[68]

An Italian friar, Gabriele Maria Berardi, claimed to have performed an exorcism on Dalí while he was in France in 1947.[69] In 2005, a sculpture of Christ on the Cross was discovered in the friar's estate. It had been claimed that Dalí gave this work to his exorcist out of gratitude,[69] and two Spanish art experts confirmed that there were adequate stylistic reasons to believe the sculpture was made by Dalí.[69]

Later years in Spain

In 1948 Dalí and Gala moved back into their house in Port Lligat, on the coast near Cadaqués. For the next three decades, he would spend most of his time there painting, taking time off and spending winters with his wife in Paris and New York.[6][38] His acceptance and implicit embrace of Franco's dictatorship were strongly disapproved of by other Spanish artists and intellectuals who remained in exile.

In 1959, André Breton organized an exhibit called Homage to Surrealism, celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Surrealism, which contained works by Dalí, Joan Miró, Enrique Tábara, and Eugenio Granell. Breton vehemently fought against the inclusion of Dalí's Sistine Madonna in the International Surrealism Exhibition in New York the following year.[70]

Late in his career Dalí did not confine himself to painting, but explored many unusual or novel media and processes: for example, he experimented with bulletist artworks.[71] Many of his late works incorporated optical illusions, negative space, visual puns and trompe l'œil visual effects. He also experimented with pointillism, enlarged half-tone dot grids (a technique which Roy Lichtenstein would later use), and stereoscopic images.[72] He was among the first artists to employ holography in an artistic manner.[73] In Dalí's later years, young artists such as Andy Warhol proclaimed him an important influence on pop art.[74]

Dalí also developed a keen interest in natural science and mathematics. This is manifested in several of his paintings, notably from the 1950s, in which he painted his subjects as composed of rhinoceros horn shapes. According to Dalí, the rhinoceros horn signifies divine geometry because it grows in a logarithmic spiral. He linked the rhinoceros to themes of chastity and to the Virgin Mary.[75] Dalí was also fascinated by DNA and the tesseract (a four-dimensional cube); an unfolding of a hypercube is featured in the painting Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus).

At some point, Dalí had a glass floor installed in a room near his studio in Lligat. He made extensive use of it to study foreshortening, both from above and from below, incorporating dramatic perspectives of figures and objects into his paintings.[72]:17–18, 172 He also delighted in using the room for entertaining guests and visitors to his house and studio. In many of his paintings, Dalí used anamorphosis, a form of eccentric and exaggerated perspective which distorts objects beyond recognition; however, when seen from a particular skewed viewpoint, a legible depiction emerges. He used the power of this technique to conceal "secret" or "forbidden" images in plain sight.[72]:20–25

Dalí's post–World War II period bore the hallmarks of technical virtuosity and an intensifying interest in optical effects, science, and religion. He became an increasingly devout Catholic, while at the same time he had been inspired by the shock of Hiroshima and the dawning of the "atomic age". Therefore, Dalí labeled this period "Nuclear Mysticism". In paintings such as The Madonna of Port Lligat (first version, 1949) and Corpus Hypercubus (1954), Dalí sought to synthesize Christian iconography with images of material disintegration inspired by nuclear physics.[76] His Nuclear Mysticism works included such notable pieces as La Gare de Perpignan (1965) and The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968–70).

In 1960, Dalí began work on his Theatre and Museum in his home town of Figueres; it was his largest single project and a main focus of his energy through 1974, when it opened. He continued to make additions through the mid-1980s.[77][78]

Dalí continued to indulge in publicity stunts and self-consciously outrageous behavior. To promote his 1962 book The World of Salvador Dalí, he appeared in a Manhattan bookstore on a bed, wired up to a machine that traced his brain waves and blood pressure. He would autograph books while thus monitored, and the book buyer would also be given the paper chart recording.[6]

In 1968, Dalí filmed a humorous television advertisement for Lanvin chocolates.[79] In this, he proclaims in French "Je suis fou du chocolat Lanvin!" ("I'm crazy about Lanvin chocolate!") while biting a morsel, causing him to become cross-eyed and his moustache to swivel upwards.[80] Also in 1968, his status as an extravagant artist was put to use in a publicity campaign ("If you got it, flaunt it!") for Braniff International Airlines.[81]

In 1969, he designed the Chupa Chups logo,[82][83] in addition to facilitating the design of the advertising campaign for the 1969 Eurovision Song Contest and creating a large on-stage metal sculpture that stood at the Teatro Real in Madrid.[84][85]

In the television programme Dirty Dalí: A Private View broadcast on Channel 4 on 3 June 2007, art critic Brian Sewell described his acquaintance with Dalí in the late 1960s, which included lying down in the fetal position without trousers in the armpit of a figure of Christ and masturbating for Dalí, who pretended to take photos while fumbling in his own trousers.[86][87]

Final years and death

In 1968, Dalí had bought a castle in Púbol for Gala; and starting in 1971 she would retreat there alone for weeks at a time. By Dalí's own admission, he had agreed not to go there without written permission from his wife.[38] His fears of abandonment and estrangement from his longtime artistic muse contributed to depression and failing health.[6]

In 1980 at age 76, Dalí's health took a catastrophic turn. His right hand trembled terribly, with Parkinson-like symptoms. His near-senile wife allegedly had been dosing him with a dangerous cocktail of unprescribed medicine that damaged his nervous system, thus causing an untimely end to his artistic capacity.[88]

In 1982, King Juan Carlos bestowed on Dalí the title of Marqués de Dalí de Púbol[89][90] (Marquis of Dalí de Púbol) in the nobility of Spain, hereby referring to Púbol, the place where he lived. The title was in first instance hereditary, but on request of Dalí changed to life only in 1983.[89]

Gala died on 10 June 1982, at the age of 87. After Gala's death, Dalí lost much of his will to live. He deliberately dehydrated himself, possibly as a suicide attempt; there are also claims that he had tried to put himself into a state of suspended animation as he had read that some microorganisms could do.[91] He moved from Figueres to the castle in Púbol, which was the site of her death and her grave.[6][38]

In May 1983, Dalí revealed what would be his last painting, The Swallow's Tail, a work heavily influenced by the mathematical catastrophe theory of René Thom.

In 1984, a fire broke out in his bedroom[92] under unclear circumstances. It was possibly a suicide attempt by Dalí, or possibly simple negligence by his staff. Dalí was rescued by friend and collaborator Robert Descharnes[93] and returned to Figueres, where a group of his friends, patrons, and fellow artists saw to it that he was comfortable living in his Theater-Museum in his final years.

There have been allegations that Dalí was forced by his guardians to sign blank canvases that would later, even after his death, be used in forgeries and sold as originals.[94] It is also alleged that he knowingly sold otherwise-blank lithograph paper which he had signed, possibly producing over 50,000 such sheets from 1965 until his death.[6] As a result, art dealers tend to be wary of late graphic works attributed to Dalí.[95]

In November 1988, Dalí entered the hospital with heart failure; a pacemaker had been implanted previously. On 5 December 1988, he was visited by King Juan Carlos, who confessed that he had always been a serious devotee of Dalí.[96] Dalí gave the king a drawing, Head of Europa, which would turn out to be Dalí's final drawing.

In early January 1989, Dali was returned to the Teatro-Museo and on his return he made his last public appearance. He was taken in a wheelchair to a room where press and TV were waiting and made a brief statement, saying:

When you are a genius, you do not have the right to die, because we are necessary for the progress of humanity.[97][98]

On the morning of 23 January 1989, while his favorite record of Tristan and Isolde played, Dalí died of heart failure at the age of 84. He is buried in the crypt below the stage of his Theatre and Museum in Figueres. The location is across the street from the church of Sant Pere, where he had his baptism, first communion, and funeral, and is only three blocks from the house where he was born.[99]

The Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation currently serves as his official estate.[100] The US copyright representative for the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation is the Artists Rights Society.[101]

Exhumation

On 26 June 2017 it was announced that a judge in Madrid had ordered the exhumation of Dali's body in order to obtain samples for a paternity suit.[102] Maria Pilar Abel Martínez, who works as a psychic and tarot card reader[103] from Figueres, Girona, born in 1956, had stated that her mother, a maid, had been having an affair with the painter in 1955. Ms Abel claimed that her mother had told her that Dalí was her father. At the time of the alleged affair, Dalí was married to Gala.[104] The exhumation took place on the evening of 20 July, and DNA was extracted.[105] On Wednesday 6 September 2017 the Dali Foundation stated that the tests carried out proved conclusively that Dali and Martinez were not related.[106][107] Joan Manuel Sevillano, manager of the Fundación Gala Salvador Dalí, denounced the exhumation as inappropriate.[108]

Symbolism

Dalí employed extensive symbolism in his work. For instance, the hallmark "melting watches" that first appear in The Persistence of Memory suggest Einstein's theory that time is relative and not fixed.[40] The idea for clocks functioning symbolically in this way came to Dalí when he was staring at a runny piece of Camembert cheese on a hot August day.[109]

The elephant is also a recurring image in Dalí's works. It appeared in his 1944 work Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening. The elephants, inspired by Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculpture base in Rome of an elephant carrying an ancient obelisk,[110] are portrayed "with long, multijointed, almost invisible legs of desire"[111] along with obelisks on their backs. Coupled with the image of their brittle legs, these encumbrances, noted for their phallic overtones, create a sense of phantom reality. "The elephant is a distortion in space", one analysis explains, "its spindly legs contrasting the idea of weightlessness with structure."[111] "I am painting pictures which make me die for joy, I am creating with an absolute naturalness, without the slightest aesthetic concern, I am making things that inspire me with a profound emotion and I am trying to paint them honestly." —Salvador Dalí, in Dawn Ades, Dalí and Surrealism.

The egg is another common Dalíesque image. He connects the egg to the prenatal and intrauterine, thus using it to symbolize hope and love;[112] it appears in The Great Masturbator and The Metamorphosis of Narcissus. The Metamorphosis of Narcissus also symbolized death and petrification. There are also giant sculptures of eggs in various locations at Dalí's house in Port Lligat[113] as well as at the Dalí Theatre and Museum in Figueres.

Various other animals appear throughout his work as well: ants point to death, decay, and immense sexual desire; the snail is connected to the human head (he saw a snail on a bicycle outside Freud's house when he first met Sigmund Freud); and locusts are a symbol of waste and fear.[112]

Both Dalí and his father enjoyed eating sea urchins, freshly caught in the sea near Cadaqués. The radial symmetry of the sea urchin fascinated Dalí, and he adapted its form to many art works. Other foods also appear throughout his work.[114]

Science

References to Dalí in the context of science are made in terms of his fascination with the paradigm shift that accompanied the birth of quantum mechanics in the twentieth century. Inspired by Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, in 1958 he wrote in his "Anti-Matter Manifesto": "In the Surrealist period, I wanted to create the iconography of the interior world and the world of the marvelous, of my father Freud. Today, the exterior world and that of physics has transcended the one of psychology. My father today is Dr. Heisenberg."[115]

In this respect, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, which appeared in 1954, in harking back to The Persistence of Memory and in portraying that painting in fragmentation and disintegration, summarizes Dalí's acknowledgment of the new science.[115]

Endeavors outside painting

Dalí was a versatile artist. Some of his more popular works are sculptures and other objects, and he is also noted for his contributions to theatre, fashion, and photography, among other areas.

Sculptures and other objects

Two of the most popular objects of the surrealist movement were Lobster Telephone and Mae West Lips Sofa, completed by Dalí in 1936 and 1937, respectively. Surrealist artist and patron Edward James commissioned both of these pieces from Dalí; James inherited a large English estate in West Dean, West Sussex when he was five and was one of the foremost supporters of the surrealists in the 1930s.[116] "Lobsters and telephones had strong sexual connotations for [Dalí]", according to the display caption for the Lobster Telephone at the Tate Gallery, "and he drew a close analogy between food and sex."[117] The telephone was functional, and James purchased four of them from Dalí to replace the phones in his retreat home. One now appears at the Tate Gallery; the second can be found at the German Telephone Museum in Frankfurt; the third belongs to the Edward James Foundation; and the fourth is at the National Gallery of Australia.[116]

The wood and satin Mae West Lips Sofa was shaped after the lips of actress Mae West, whom Dalí apparently found fascinating.[37] West was previously the subject of Dalí's 1935 painting The Face of Mae West. The Mae West Lips Sofa currently resides at the Brighton and Hove Museum in England.

Between 1941 and 1970, Dalí created an ensemble of 39 pieces of jewelry; many pieces are intricate, and some contain moving parts. The most famous assemblage, The Royal Heart, is made of gold and is encrusted with 46 rubies, 42 diamonds, and four emeralds, created in such a way that the center "beats" much like a real heart. Dalí himself commented that "Without an audience, without the presence of spectators, these jewels would not fulfill the function for which they came into being. The viewer, then, is the ultimate artist."[118] The "Dalí – Joies" ("The Jewels of Dalí") collection is in the Dalí Theater Museum in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain.

Dalí took a stab at industrial design in the 1970s with a 500-piece run of the upscale Suomi tableware by Timo Sarpaneva that Dalí decorated for the German Rosenthal porcelain maker's "Studio Linie".[119]

Theatre and film

In theatre, Dalí constructed the scenery for Federico García Lorca's 1927 romantic play Mariana Pineda.[120] For Bacchanale (1939), a ballet based on and set to the music of Richard Wagner's 1845 opera Tannhäuser, Dalí provided both the set design and the libretto.[121] Bacchanale was followed by set designs for Labyrinth in 1941 and The Three-Cornered Hat in 1949.[122]

Dalí became intensely interested in film when he was young, going to the theatre most Sundays. He was part of the era where silent films were being viewed and drawing on the medium of film became popular. He believed there were two dimensions to the theories of film and cinema: "things themselves", the facts that are presented in the world of the camera; and "photographic imagination", the way the camera shows the picture and how creative or imaginative it looks.[123] Dalí was active in front of and behind the scenes in the film world.

He is credited as co-creator of Luis Buñuel's surrealist film Un Chien Andalou, a 17-minute French art film co-written with Luis Buñuel that is widely remembered for its graphic opening scene simulating the slashing of a human eyeball with a razor. In Un Chien Andalou, surreal imagery and irrational discontinuities in time and space produce a dreamlike quality.[124] The second film he produced with Buñuel was entitled L'Age d'Or, and it was performed at Studio 28 in Paris in 1930. L'Age d'Or was "banned for years after fascist and anti-Semitic groups staged a stink bomb and ink-throwing riot in the Paris theater where it was shown".[125]

Both of these films, Un Chien Andalou and L'Age d'Or, have had a tremendous impact on the independent surrealist film movement. "If Un Chien Andalou stands as the supreme record of Surrealism's adventures into the realm of the unconscious, then L'Âge d'Or is perhaps the most trenchant and implacable expression of its revolutionary intent".[126]

Dalí worked with other famous filmmakers, such as Alfred Hitchcock. The most well-known of his film projects is probably the dream sequence in Hitchcock's Spellbound, which delves into themes of psychoanalysis. Hitchcock needed a dreamlike quality to his film, which dealt with the idea that a repressed experience can directly trigger a neurosis, and he knew that Dalí's work would help create the atmosphere he wanted in his film.

Dalí also worked with Walt Disney on the short film production Destino. Completed in 2003 by Baker Bloodworth and Walt's nephew Roy E. Disney, it contains dreamlike images of strange figures flying and walking about. It is based on Mexican songwriter Armando Dominguez' song "Destino". When Disney hired Dalí to help produce the film in 1946, they were not prepared for the quantity of work that lay ahead. For eight months, they worked on it continuously, until their efforts had to stop when they realized they were in financial trouble. However, it was eventually finished 48 years later, and shown in various film festivals. The film consists of Dalí's artwork interacting with Disney's character animation.

In 1960 Dalí and the photographer Philippe Halsman made a documentary video called Chaos and Creation, that showed him creating a painting.[127]

Dalí completed only one other film in his lifetime, Impressions of Upper Mongolia (1975), in which he narrated a story about an expedition in search of giant hallucinogenic mushrooms. The imagery was based on microscopic uric acid stains on the brass band of a ballpoint pen on which Dalí had been urinating for several weeks.[128]

In the mid-1970s, film director Alejandro Jodorowsky cast Dali in the role of the Padishah Emperor in a production of Dune, based on the novel by Frank Herbert. According to the 2013 documentary on the film, Jodorowsky's Dune, Jodorowsky met Dali in the King Cole Bar in the St. Regis hotel in Manhattan to discuss the role. Dali expressed interest in the film but required as a condition of appearing that he be made the highest-paid actor in Hollywood. Jodorowsky accordingly cast Dali as the emperor, but he planned to cut Dali's screen time to mere minutes, promising he be the highest-paid actor on a per minute basis. The film was ultimately never made.[129]

In the year 1927, Dali began to write the libretto for an opera, which he called Être Dieu (To Be God). He wrote this together with Federico Garcia Lorca one afternoon in the Café Regina Victoria in Madrid. In 1974, for a recording in Paris, the opera was adapted by the Spanish writer Manuel Vazquez Montalban, who wrote the libretto, while the music was created by Igor Wakhevitch. During the recording, however, Dali refused to follow the text written by Montalban, and instead, began to improvise in the belief that “Salvador Dali never repeats himself.”

Fashion and photography

_09633u.jpg)

Dalí built a repertoire in the fashion and photography businesses as well. His cooperation with Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli was well-known, when Dalí was commissioned to produce a white dress with a lobster print. Other designs Dalí made for her include a shoe-shaped hat, and a pink belt with lips for a buckle. He was also involved in creating textile designs and perfume bottles. In 1950, Dalí created a special "costume for the year 2045" with Christian Dior.[121]

Photographers with whom he collaborated include Man Ray, Brassaï, Cecil Beaton, and Philippe Halsman. With Man Ray and Brassaï, Dalí photographed nature; with the others, he explored a range of obscure topics, including (with Halsman) the Dalí Atomica series (1948) — inspired by his painting Leda Atomica — which in one photograph depicts "a painter's easel, three cats, a bucket of water, and Dalí himself floating in the air."[121]

One of Dalí's most unorthodox artistic creations may have been an entire persona, in addition to his own. At a French nightclub in 1965, Dalí met Amanda Lear, a fashion model then known as Peki D'Oslo.[130] Lear became his protégée and muse,[130] later writing about their affair in her authorized biography My Life With Dalí (1986).[131] Transfixed by the mannish, larger-than-life Lear, Dalí masterminded her successful transition from modeling to the music world, advising her on self-presentation and helping spin mysterious stories about her origin as she took the disco-art scene by storm. According to Lear, she and Dalí were united in a "spiritual marriage" on a deserted mountaintop.[130] She was referred to as Dalí's "Frankenstein",[132] and some observers believed Lear's assumed name was a pun on the French phrase "L'Amant Dalí", or "Lover of Dalí". Lear took the place of an earlier muse, Ultra Violet (Isabelle Collin Dufresne), who had left Dalí's side to join The Factory of Andy Warhol.[133]

Both former apprentices would go on to successfully promote their own careers in the arts. On April 10, 2005, they joined a panel discussion "Reminiscences of Dalí: A Conversation with Friends of the Artist" as part of a symposium "The Dalí Renaissance" for a major retrospective Dalí show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[134] Their conversation is recorded in the 236-page exhibition catalog The Dalí Renaissance: New Perspectives on His Life and Art after 1940.[135]

Architecture

Architectural achievements include his Port Lligat house near Cadaqués, as well as his Theatre and Museum in Figueres. A major work outside of Spain was the temporary Dream of Venus surrealist pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair, which contained within it a number of unusual sculptures and statues, including live performers posing as statues.[61]

Literary works

Under the encouragement of poet Federico García Lorca, Dalí attempted an approach to a literary career through the means of the "pure novel". In his only novel Hidden Faces (1944), Dalí describes, in vividly visual terms, the intrigues and love affairs of a group of dazzling, eccentric aristocrats who, with their luxurious and extravagant lifestyle, symbolize the decadence of the 1930s. The Comte de Grandsailles and Solange de Cléda pursue an awkward love affair, but property transactions, interwar political turmoil, the French Resistance, his marriage to another woman and her responsibilities as a landowner and businesswoman drive them apart. It is variously set in Paris, rural France, Casablanca in North Africa and Palm Springs in the United States. Secondary characters include aging widow Barbara Rogers, her bisexual daughter Veronica, Veronica's sometime female lover Betka, and Baba, a disfigured US fighter pilot. The novel concludes at the end of the Second World War, with Solange dying before Grandsailles can return to his former property and reunite with her.[136] The novel was written in New York, and translated by Haakon Chevalier.

His other, nonfictional literary works include The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942), Diary of a Genius (1952–63), and Oui: The Paranoid-Critical Revolution (1927–33).

Graphic arts

The artist worked extensively in the graphic arts, producing many etchings and lithographs. While his early work in printmaking is equal in quality to his important paintings, as he grew older he would sell the rights to images but not be involved in the print production itself. In addition, a large number of fakes were produced in the 1980s and 1990s, thus further confusing the Dalí print market.[95]

Politics and personality

Dalí's politics played a significant role in his emergence as an artist. In his youth, he embraced both anarchism and communism,[137] though his writings tell anecdotes of making radical political statements more to shock listeners than from any deep conviction. This was in keeping with Dalí's allegiance to the Dada movement.[28][138]

As he grew older his political allegiances changed, especially as the Surrealist movement went through transformations under the leadership of the Trotskyist writer André Breton, who is said to have called Dalí in for questioning on his politics. In his 1970 book Dalí by Dalí, Dalí declared himself to be both an anarchist and monarchist.[139]

With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), Dalí fled from the fighting and refused to align himself with any group. He did the same during World War II (1939–1945), for which he was heavily criticized; George Orwell accused him of "scuttling off like a rat as soon as France is in danger" after Dalí had prospered in France during the pre-war years. "When the European War approaches he has one preoccupation only: how to find a place which has good cookery and from which he can make a quick bolt if danger comes too near", Orwell observed.[140] In a notable 1944 review of Dalí's autobiography, Orwell wrote, "One ought to be able to hold in one's head simultaneously the two facts that Dalí is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being".[140]

After his return to Catalonia post World War II, Dalí moved closer to the authoritarian regime of Francisco Franco. Some of Dalí's statements were supportive, congratulating Franco for his actions aimed "at clearing Spain of destructive forces".[138] Dalí, having returned to the Catholic faith and becoming increasingly religious as time went on, may have been referring to the Republican atrocities during the Spanish Civil War.[141][142] Dalí sent telegrams to Franco, praising him for signing death warrants for prisoners.[138] He even met Franco personally,[143] and painted a portrait of Franco's granddaughter.[144]

He also once sent a telegram praising the Conducător, Romanian Communist leader Nicolae Ceauşescu, for his adoption of a scepter as part of his regalia. The Romanian daily newspaper Scînteia published it, without suspecting its mocking aspect.[145] One of Dalí's few possible bits of open disobedience was his continued praise of Federico García Lorca even in the years when Lorca's works were banned.[27]

Dalí, a colorful and imposing presence with his ever–present long cape, walking stick, haughty expression, and upturned waxed moustache, was famous for having said that "every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dalí".[146] In the 1960s, he gave the actress Mia Farrow a dead mouse in a bottle, hand-painted, which her mother, actress Maureen O'Sullivan, demanded be removed from her house.[147]

Dali's religious views were a matter of interest. In interviews Dali revealed his mysticism. In his later years, while still remaining a Roman Catholic, Dalí also claimed to be an agnostic.[148] In his 1942 autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dali, he sums up his life story with an impassioned defense of the Catholic Church and religion in general. In one passage he states "I believe, above all, in the real and unfathomable force of the philosophic Catholicism of France and in that of the militant Catholicism of Spain."[149] Dali also had great respect for the Jesuit priest and philosopher Teilhard de Chardin[150] and was fascinated by his Omega Point theory (a theory wherein the universe evolves towards an ultimate state of complexity and spiritual consciousness).[151] Dali's 1959 painting The Ecumenical Council is said to represent the "interconnectedness" of the Omega Point.[152]

Dalí frequently traveled with his pet ocelot Babou, even bringing it aboard the luxury ocean liner SS France.[153] He was also known to avoid paying tabs at restaurants by drawing on the checks he wrote. His theory was the restaurant would never want to cash such a valuable piece of art, and he was usually correct.[154]

Besides visual puns, Dalí shared in the surrealist delight in verbal puns, obscure allusions, and word games. He often spoke in a bizarre combination of French, Spanish, Catalan, and English which was sometimes amusing as well as arcane.

When interviewed by Mike Wallace on his 60 Minutes television show, Dalí kept referring to himself in the third person, as the "Divino Dalí" (Divine Dalí), and told the startled Wallace matter-of-factly that he did not believe in his death.[155] On January 27, 1957, he was the mystery guest on the US panel show What's My Line? and signed the chalkboard with thick white paint.[156] His answers were misleading and prompted guidance from host John Daly.[157][158]

Dali appeared in public on a number of occasions with an anteater, notably on a lead in Paris in 1969 and on The Dick Cavett Show on March 6, 1970 when he carried a small anteater on-stage. On the show, he surprised fellow guest Lillian Gish by flinging the anteater onto her lap.[159]

Legacy

In Carlos Lozano's biography, Sex, Surrealism, Dalí, and Me, produced with the collaboration of Clifford Thurlow, Lozano makes it clear that Dalí never stopped being a surrealist. As Dalí said of himself: "the only difference between me and the surrealists is that I am a surrealist".[62]

Salvador Dalí has been cited as a major inspiration by many modern artists, such as Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, and most other modern surrealists. Salvador Dalí's manic expression and famous moustache have made him something of a cultural icon for the bizarre and surreal. He has been portrayed on film by Robert Pattinson in Little Ashes (2008), and by Adrien Brody in Midnight in Paris (2011). He was also parodied in a series of painting skits on Captain Kangaroo as "Salvador Silly" (played by Cosmo Allegretti) and in a Sesame Street muppet skit as "Salvador Dada" (an orange gold Anything Muppet performed by Jim Henson).

The Salvador Dalí Desert in Bolivia and the Dali crater on the planet Mercury are named for him.

Honours

- 1964: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic[160]

- 1972: Associate member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium[161]

- 1981: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III[162]

- 1982: Created 1st Marqués de Dalí de Púbol, by King Juan Carlos

- Member of the Legion of Honour

- Associate member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut de France

List of selected works

Dalí produced over 1,500 paintings in his career[163] in addition to producing illustrations for books, lithographs, designs for theatre sets and costumes, a great number of drawings, dozens of sculptures, and various other projects, including an animated short film for Disney. He also collaborated with director Jack Bond in 1965, creating a movie titled Dalí in New York. Below is a chronological sample of important and representative work, as well as some notes on what Dalí did in particular years.[4]

- 1910 Landscape Near Figueras

- 1913 Vilabertin

- 1916 Fiesta in Figueras (begun 1914)

- 1917 View of Cadaqués with Shadow of Mount Pani

- 1918 Crepuscular Old Man (begun 1917)

- 1919 Port of Cadaqués (Night) (begun 1918) and Self-portrait in the Studio

- 1920 The Artist's Father at Llane Beach and View of Portdogué (Port Aluger)

- 1921 The Garden of Llaner (Cadaqués) (begun 1920) and Self-portrait

- 1922 Cabaret Scene and Night Walking Dreams

- 1923 Self Portrait with L'Humanite and Cubist Self Portrait with La Publicitat

- 1924 Still Life (Syphon and Bottle of Rum) (for García Lorca) and Portrait of Luis Buñuel

- 1925 Large Harlequin and Small Bottle of Rum and a series of fine portraits of his sister Anna Maria, most notably Figure at a Window

- 1926 The Basket of Bread, Girl from Figueres and Girl with Curls

- 1927 Composition with Three Figures (Neo-Cubist Academy) and Honey is Sweeter than Blood (his first important surrealist work)

- 1929 Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) film in collaboration with Luis Buñuel, The Lugubrious Game, The Great Masturbator, The First Days of Spring, and The Profanation of the Host

- 1930 L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age) film in collaboration with Luis Buñuel

- 1931 The Persistence of Memory (his most famous work, featuring the "melting clocks"), The Old Age of William Tell, and William Tell and Gradiva

- 1932 The Spectre of Sex Appeal, The Birth of Liquid Desires, Anthropomorphic Bread, and Fried Eggs on the Plate without the Plate. The Invisible Man (begun 1929) completed (although not to Dalí's own satisfaction)

- 1933 Retrospective Bust of a Woman (mixed media sculpture collage) and Portrait of Gala With Two Lamb Chops Balanced on Her Shoulder, Gala in the Window

- 1934 The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table and A Sense of Speed

- 1935 Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet's Angelus and The Face of Mae West

- 1936 Autumn Cannibalism, Lobster Telephone, Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) and two works titled Morphological Echo (the first of which began in 1934)

- 1937 Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Swans Reflecting Elephants, The Burning Giraffe, Sleep, The Enigma of Hitler, Mae West Lips Sofa and Cannibalism in Autumn

- 1938 The Sublime Moment and Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach

- 1939 Shirley Temple, The Youngest, Most Sacred Monster of the Cinema in Her Time

- 1940 Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire, The Face of War

- 1941 Honey is Sweeter than Blood

- 1943 The Poetry of America and Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man

- 1944 Galarina and Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening

- 1944–48 Hidden Faces, a novel

- 1945, Basket of Bread—Rather Death than Shame and Fountain of Milk Flowing Uselessly on Three Shoes; also this year, Dalí collaborated with Alfred Hitchcock on a dream sequence to the film Spellbound, to mutual dissatisfaction

- 1946 The Temptation of St. Anthony

- 1948 The Elephants

- 1949 Leda Atomica and The Madonna of Port Lligat. Dalí returned to Catalonia this year

- 1951 Christ of Saint John of the Cross and Exploding Raphaelesque Head

- 1951 Katharine Cornell, a portrait of the famed actress

- 1952 Galatea of the Spheres

- 1954 The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (begun in 1952), Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), and Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity

- 1955 The Sacrament of the Last Supper, Lonesome Echo, record album cover for comedian Jackie Gleason

- 1956 Still Life Moving Fast, Rinoceronte vestido con puntillas

- 1957 Santiago el Grande oil on canvas on permanent display at Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, NB, Canada

- 1958 The Meditative Rose

- 1959 The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus

- 1960 Composición Numérica (de fond préparatoire inachevé), in acrylic and oil on canvas

- 1960 Dalí began work on the Teatro-Museo Gala Salvador Dalí and Portrait of Juan de Pareja, the Assistant to Velázquez

- 1961 El Triomf I el Rodoli de la Gala I en Dali, a composite of Dalí's favorite graphical motifs which was gifted to his friend Fages de Climent, and later sold, leading to a cosmetic and beauty company gaining access to it and the rights to build Elevatione by Salvador Dali, a luxury cosmetic and makeup company in 2013.

- 1963–1964 They Will All Come from Saba a work in water color depicting the Magi, at St. Petersburg's Dalí Museum

- 1965 Dalí donated a gouache, ink and pencil drawing of the Crucifixion to the Rikers Island jail in New York City. The drawing hung in the inmate dining room from 1965 to 1981.[164]

- 1965 Dalí in New York

- 1967 Tuna Fishing

- 1969 Chupa Chups logo

- 1969 Improvisation on a Sunday Afternoon, television collaboration with the British progressive rock group Nirvana

- 1970 The Hallucinogenic Toreador, purchased in 1969 by Reynolds and Eleanor Morse before it was completed

- 1972 Gala, Elena Ivanovna Diakonova – dit., GALA Bronze sculpture, piece unique[165]

- 1973 Les Diners de Gala, an ornately illustrated cookbook

- 1976 Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea

- 1977 Dalí's Hand Drawing Back the Golden Fleece in the Form of a Cloud to Show Gala Completely Nude, Very Far Away Behind the Sun (stereoscopical pair of paintings)

- 1981 Femme à la tête de rose In 1935 Dali painted the Woman with the head of roses homage to the verse of René Crevel appeared in the surrealist magazine "Le Minotaure": "But it appears and it is spring. A ball of flowers will serve as his head. His is both the hive and the bouquet..." Decades later, he made it an elevated sculpture and Supported by crutches.This beautiful phytomorphic creature expresses both grace and rigidity, femininity and animality.[166][167]

- 1983 The Swallow's Tail, Dalí's final painting

- 2003 Destino, an animated short film originally a collaboration between Dalí and Walt Disney, is released. Production on Destino began in 1945.

Dalí museums and permanent exhibitions

Current

- Art Bank, private exhibition - Pargas, Finland

- Dalí – Die Ausstellung am Potsdamer Platz - Berlin, Germany, a museum with a permanent exhibition

- Dalí Theatre and Museum – Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, holds the largest collection of Dalí's work

- Dalí Universe - London, England, holds a significant collection

- Dali17 - Monterey, California, US, permanent exhibition

- Espace Dalí – Paris, France, holds a significant collection

- Gala Dalí House-Museum - Castle of Púbol in Púbol, Catalonia, Spain

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia (Reina Sofia Museum) - Madrid, Spain, holds a significant collection

- Museum-Gallery Xpo: Salvador Dali - Bruges, Belgium, permanent exhibition

- Salvador Dalí Gallery - San Juan Capistrano, California, US; holds a significant collection

- Salvador Dalí House-Museum - Port Lligat, Catalonia, Spain

- Salvador Dali Museum – St Petersburg, Florida, US, contains the collection of Reynolds and Eleanor Morse, and over 1500 works by Dalí, including seven large "masterworks"

Former

- Dalí Universe – Venice, Italy (permanently closed)

- Rikers Island jail - New York City, US, the unlikeliest venue for Dalí's work. A sketch of the Crucifixion that he donated to the jail in 1965 hung in the inmate dining room for 16 years before it was moved to the prison lobby for safekeeping. The drawing was stolen from that location in March 2003 and has not been recovered.[164]

Major temporary exhibitions

- The Dalí Renaissance: New Perspectives on His Life and Art after 1940 (2005) Philadelphia Museum of Art[135]

Gallery

- Gala in the Window (1933), Marbella

The Rainbow (1972), M.T. Abraham Foundation

The Rainbow (1972), M.T. Abraham Foundation- Rinoceronte vestido con puntillas (1956), Puerto José Banús

_08.jpg) Plaza de Dalí (Dalí Square), Madrid

Plaza de Dalí (Dalí Square), Madrid- Perseo (Perseus), Marbella

Children at Dalí exhibition in Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul

Children at Dalí exhibition in Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul

See also

- Case of Aimée

- Little Ashes

- List of Spanish artists

- Salvador Dalí and Dance

References

- ↑ "Dali". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ "Dali". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- ↑ "Phelan, Joseph; The Salvador Dalí Show". Artcyclopedia.com. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- 1 2 Dalí, Salvador. (2000) Dalí: 16 Art Stickers, Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41074-9.

- ↑ Ian Gibson (1997). The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí. W. W. Norton & Company. Gibson found out that "Dalí" (and its many variants) is an extremely common surname in Arab countries like Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria or Egypt. On the other hand, also according to Gibson, Dalí's mother's family, the Domènech of Barcelona, had Jewish roots.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Meisler, Stanley (April 2005). "The Surreal World of Salvador Dalí". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- 1 2 Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 238–9

- ↑ Saladyga, Stephen Francis (2006). "The Mindset of Salvador Dalí". Lamplighter. Niagara University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2006.

- ↑ Birth certificate and "Dalí Biography". Dalí Museum. Dalí Museum. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ↑

- ↑ País, Ediciones El (February 14, 2008). "Dalí recupera su casa natal, que será un museo en 2010". Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1997) pp. 6, 459, 633, 689

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Llongueras, Lluís. (2004) Dalí, Ediciones B – Mexico. ISBN 84-666-1343-9.

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 16, 82, 634, 644

- 1 2 Rojas, Carlos. Salvador Dalí, Or the Art of Spitting on Your Mother's Portrait, Penn State Press (1993). ISBN 0-271-00842-3.

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1997)

- ↑ Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, 1948, London: Vision Press, p.33

- ↑ Salvador Dalí. SINA.com. Retrieved on July 31, 2006.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí biography on astrodatabank.com. Retrieved September 30, 2006.

- 1 2 Dalí, Secret Life, p.2

- ↑ "Dalí Biography 1904–1989 – Part Two". artelino.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2006.

- ↑ van Charli, Luca (21 October 2013). "Salvador Dali Played Football?". Medium. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 82

- ↑ Dalí, Secret Life, pp.152–153

- ↑ As listed in his prison record of 1924, aged 20. However, his hairdresser and biographer, Luis Llongueras, stated Dalí was 1.74 metres (5 ft 8 1⁄2 in) tall.

- ↑ For more in-depth information about the Lorca-Dalí connection see Lorca-Dalí: el amor que no pudo ser and The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, both by Ian Gibson.

- 1 2 Bosquet, Alain, Conversations with Dalí, 1969. p. 19–20. (PDF)

- 1 2 La dada fotogràfica, Gaseta de les Arts, n° 6, February 1929

- ↑ Fèlix Fanés, Salvador Dalí: The Construction of the Image, 1925-1930, Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 0300091796

- ↑ Exposició Salvador Dalí, Galeries Dalmau, 14–28 November 1925, exhibition catalogue

- ↑ Elisenda Andrés Pàmies, Les Galeries Dalmau, un projecte de modernitat a la ciutat de Barcelona, 2012-13, Facultat d’Humanitats, Universitat Pompeu Fabra

- ↑ Exposició de Salvador Dalí, Galeries Dalmau, Passeig de Gràcia, 31 December 1926 – 14 January 1927, exhibition catalogue (other version)

- ↑ "Paintings Gallery No. 5". Dali-gallery.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ Hodge, Nicola, and Libby Anson. The A–Z of Art: The World's Greatest and Most Popular Artists and Their Works. California: Thunder Bay Press, 1996. Online citation.

- ↑ "Phelan, Joseph". Artcyclopedia.com. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ Koller, Michael (January 2001). "Un Chien Andalou". Senses of Cinema (in French). Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- 1 2 Shelley, Landry. "Dalí Wows Crowd in Philadelphia". Unbound (The College of New Jersey) Spring 2005. Retrieved on July 22, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 "Gala Biography". Dalí. Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Clocking in with Salvador Dalí: Salvador Dalí's Melting Watches (PDF) from the Salvador Dalí Museum. Retrieved on August 19, 2006.

- 1 2 Salvador Dalí, La Conquête de l'irrationnel (Paris: Éditions surréalistes, 1935), p. 25.

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 323

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1997) p. 492

- ↑ Amengual, Margalida (14 December 2016). "An opera on the relationship between Salvador Dalí and Gala arrives at Barcelona's Liceu". Catalan News Agency (CNA). Intracatalònia, SA. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Current Biography 1940, pp. 219–220

- ↑ Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel, Vintage 1984. ISBN 0-8166-4387-3

- ↑ Greeley, Robin Adèle (2006). Surrealism and the Spanish Civil War, Yale University Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-300-11295-5.

- ↑ Clements, Paul (2016). The Creative Underground : Art, Politics and Everyday Life. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781317501282.

- ↑ Shanes, Eric (2012). The Life and Masterworks of Salvador Dalí. Parkstone. p. 53. ISBN 1780428790.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí, Louis Pauwels, Les passions selon Dalí, Denoël, 1968

- ↑ Pierre Ajame, La Double vie de Salvador Dali: récit, Éditions Ramsay, 1984, p. 125

- ↑ Jackaman, Rob. (1989) The Course of English Surrealist Poetry Since the 1930s, Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-932-6.

- ↑ Current Biography 1940, p219

- ↑ "Program Notes by Andy Ditzler (2005) and Deborah Solomon, Utopia Parkway: The Life of Joseph Cornell (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003)". Andel.home.mindspring.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2005. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Salvador Dali Lobster Telephone". National Gallery of Australia. August 1994. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí Exhibition, Exhibition Catalogue – February 16 through May 15, 2005

- ↑ Fischer, John. "Salvador Dali Exhibition". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ Bretell, Richard R. (1995). Impressionist paintings, drawings, and sculpture from the Wendy and Emery Reeves Collection. Dallas Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-936227-15-3.

- ↑ "Salvador Dalí's Biography - Gala - Salvador Dali Foundation". salvador-dali.org. Archived from the original on November 6, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Paris 1937". google.com. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Leo and His Circle". google.com. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- 1 2 Schaffner, Ingrid, Photogr. by Eric Schaal (2002). Salvador Dalí's "Dream of Venus": the surrealist funhouse from the 1939 World's Fair (1. ed.). New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1568983592.

- 1 2 Artcyclopedia: Salvador Dalí. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ↑ Coppens, Philip. "Salvador Dali: painting the fourth dimension". PhilipCoppins.com. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ Schmalz, David. "A world-class Salvador Dali art collection comes to Monterey". Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ↑ "Dali". Sousa Mendes Foundation. 20 June 1940. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- 1 2 Descharnes, Robert and Nicolas. Salvador Dalí. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1993. p. 35.

- ↑ Crowder, Bland (January 31, 2014). "¡Hola, Dalí!". Virginia Living. Cape Fear Publishing. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ↑ Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel (Vintage, 1984) ISBN 0-8166-4387-3

- 1 2 3 Dalí's gift to exorcist uncovered Catholic News, October 14, 2005.

- ↑ Ignacio Javier López. The Old Age of William Tell (A study of Buñuel's Tristana). MLN 116 (2001): 295–314.

- ↑ BP Editor. "The Phantasmagoric Universe—Espace Dalí À Montmartre". Bonjour Paris (in French). Archived from the original on 28 May 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- 1 2 3 Ades, ed. by Dawn (2000). Dalí's optical illusions : [Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, January 21 - March 26, 2000 : Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, April 19 - June 18, 2000 ; Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, July 25 - October 1, 2000]. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0300081770.

- ↑ The History and Development of Holography. Holophile. Retrieved on August 22, 2006.

- ↑ "Hello, Dalí". Carnegie Magazine. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ↑ Elliott H. King in Dawn Ades (ed.), Dalí, Bompiani Arte, Milan, 2004, p. 456.

- ↑ "Salvador Dalí Bio, Art on 5th". Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved July 22, 2006.

- ↑ Pitxot, Antoni; Montse Aguer Teixidor; photography, Jordi Puig; translation, Steve Cedar (2007). The Dalí Theatre-Museum. Sant Lluís, Menorca: Triangle Postals. ISBN 9788484782889.

- ↑ "Figueres: Teatre Museu Dalí - History". Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí. 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí at Le Meurice Paris and St Regis in New York Andreas Augustin, ehotelier.com, 2007

- ↑ Salvador Dali - Chocolat Lanvin $ on YouTube

- ↑ Namath: A Biography, Mark Kriegel page 290

- ↑ H. Vázquez, Carlos (July 2, 2015). "Cuando Dalí reinventó Chupa Chups". Forbes (in Spanish). Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Barud, Bibiñe (January 23, 2018). "Salvador Dalí diseñó el logo de las paletas Chupa Chups y... no hay nada más surreal que eso". BuzzFeed (in Spanish). Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Calandria, Juan (March 29, 2017). "Madrid acoge el festival de Eurovisión de 1969". Eurovision Planet (in Spanish). Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Jacques (April 26, 2009). "40 años de Eurovisión 1969 – Segunda parte: Canciones 1-5". Ole Vision (in Spanish). AEV España. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Scotsman review of Dirty Dalí". The Scotsman. UK. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ Sewell, Brian (January 1, 2007). "The Dali I knew". This is London. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007.

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1997)

- 1 2 Excerpts from the BOE – Website Heráldica y Genealogía Hispana

- ↑ Dalí as "Marqués de Dalí de Púbol" – Boletín Oficial del Estado, the official gazette of the Spanish government

- ↑ "Salvador Dali - Paths to Immortality". History of Art. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ "Dalí Resting at Castle After Injury in Fire". The New York Times. September 1, 1984. Retrieved July 22, 2006.

- ↑ Décès de Robert Descharnes, l'homme qui avait sauvé Salvador Dalí (in French)

- ↑ Mark Rogerson (1989). The Dalí Scandal: An Investigation. Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-03786-5.

- 1 2 Forde, Kevin (2011). Investing in Collectables: An Investor's Guide to Turning Your Passion Into a Portfolio. Wiley. p. 170. ISBN 1742468217.

- ↑ Etherington-Smith, Meredith, The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dalí p. 411, 1995 Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80662-2

- ↑ Somatemps Catalanitat és Hispanitat, Última entrevista a Dalí: “¡Viva el Rey, viva España, viva Cataluña!” (video), published 26 March 2017

- ↑ El País, Dalí vuelve a casa, 17 July 1986

- ↑ Etherington-Smith, Meredith, The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dalí pp. xxiv, 411–412, 1995 Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80662-2

- ↑ "Salvador Dalí's Museums - Gala - Salvador Dali Foundation". www.salvador-dali.org. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Most frequently requested artists list of the Artists Rights Society". Artists Rights Society. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009.

- ↑ "La exhumación del cuerpo de Salvador Dalí se inicia hoy a partir de las 20 horas". Marca (in Spanish). 20 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ Radford, Ben (2018). "DNA Test: Dalí Not Father of Spanish Psychic". Skeptical Inquirer. 42 (1): 6.

- ↑ "Salvador's Body to be Exhumed". bbc.co.uk. 26 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ Redacción (20 July 2017). "Muelas, uñas y huesos: las pruebas que demostrarán la supuesta paternidad de Dalí". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ Salvador Dali: DNA test proves woman is not his daughter, BBC News

- ↑ Josep, Fita (21 July 2017). ""El bigote de Dalí sigue intacto, marcando las 10 y 10, es un milagro"". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Barcelona. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ Grael, Vanessa (21 July 2017). "La fundación Gala Salvador Dalí carga contra la exhumación del pintor: "Queremos una compesación patrimonial"". El Mundo (in Spanish). Figueres. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (New York: Dial Press, 1942), p. 317.

- ↑ Michael Taylor in Dawn Adès (ed.), Dalí (Milan: Bompiani, 2004), p. 342

- 1 2 "Dalí Universe Collection". County Hall Gallery. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- 1 2 "Salvador Dalí's symbolism". County Hall Gallery. Archived from the original on 2 December 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ↑ Stone, Peter (2007-05-07). Frommer's Barcelona (2nd ed.). Wiley Publishing Inc. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-470-09692-5. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "Salvador Dali: Liquid Desire". ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- 1 2 Datta, Suman. "Dalí: Explorations into the domain of science". The Triangle Online. College Publisher. p. 1. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- 1 2 Lobster telephone. National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved on August 4, 2006.

- ↑ Tate Collection | Lobster Telephone by Salvador Dalí. Tate Online. Retrieved on August 4, 2006.

- ↑ Owen Cheatham Foundation. Dali, a study of his art-in-jewels: the collection of the Owen Cheatham Foundation. New York: New York Graphic Society. 1959. p. 14.

- ↑ "Faenza-Goldmedaille für SUOMI". Artis. 29: 8. 1976. ISSN 0004-3842.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Federico García Lorca". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Dalí Rotterdam Museum Boijmans. Paris Contemporary Designs. Retrieved on August 8, 2006.

- ↑ "Past Exhibitions". Haggerty Museum of Art. Marquette University. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ↑ "Dali & Film" Edt. Gale, Matthew. Salvador Dalí Museum Inc. St Petersburg, Florida. 2007.

- ↑ Eberwein, Robert T. (2014). Film and the Dream Screen: A Sleep and a Forgetting. Princeton University Press. p. 83. ISBN 1400853893.

- ↑ "L'Âge d'Or (The Golden Age)" Harvard Film Archive. 2006. April 10, 2008.

- ↑ Short, Robert. "The Age of Gold: Surrealist Cinema, Persistence of Vision" Vol. 3, 2002.

- ↑ Short, Robert, Stephen Barber, and Candice Black (2008). The Age of Gold: Surrealist Cinema. Los Angeles, Calif: Solar. p. 174. ISBN 9780979984709.

- ↑ Elliott H. King, Dalí, Surrealism and Cinema, Kamera Books 2007, p. 169.

- ↑ "Jodorowsky's Dune - Official Website of the Documentary - Synopsis". jodorowskysdune.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Prose, Francine. (2000) The Lives of the Muses: Nine Women and the Artists they Inspired. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-055525-4.

- ↑ Lear, Amanda. (1986) My Life with Dalí. Beaufort Books. ISBN 0-8253-0373-7.

- ↑ Lozano, Carlos. (2000) Sex, Surrealism, Dalí, and Me. Razor Books Ltd. ISBN 0-9538205-0-5.

- ↑ Etherington-Smith, Meredith. (1995) The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dalí. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80662-2.

- ↑ "Symposium announcement" (PDF). The Dalí Renaissance: An international symposium. Philadelphia Museum of Art. April 10–11, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- 1 2 Taylor, edited by Michael R. (2008). The Dalí renaissance : new perspectives on his life and art after 1940 : an international symposium. New Haven, Connecticut: Philadelphia Museum of Art, distributed by Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300136470.

- ↑ Salvador Dali: Hidden faces: London: Owen: 1973

- ↑ Robin Adèle Greeley, Surrealism and the Spanish Civil War, Yale University Press, 2006, pp. 62-63, ISBN 0300112955

- ↑ Salvador Dalí, Dalí by Dalí, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1970

- 1 2 Orwell, George "Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí". theorwellprize.co.uk. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ↑ "Payne, Stanley G., A History of Spain and Portugal, Vol. 2, Ch. 26, p. 648–651 (Print Edition: University of Wisconsin Press, 1973) (Library of Iberian Resources Online, Accessed May 15, 2007)". Libro.uca.edu. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ De la Cueva, Julio, "Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War", Journal of Contemporary History, Vol XXXIII – 3, 1998.

- ↑ "Fun with Franco!". andrewcusack.com. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Franco and Dalí". Granger. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ Michael Taylor, The Dalí Renaissance: New Perspectives on His Life and Art After 1940, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2008, ISBN 0300136471

- ↑ The Surreal World of Salvador Dalí. Smithsonian Magazine. 2005. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- ↑ "Salvador Dalí & Mia Farrow, a Surreal Friendship". lidogallery. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ Robert Descharnes, Gilles Néret (1994). Salvador Dalí, 1904-1989. Benedikt Taschen. p. 166. ISBN 9783822802984.

Dali, dualist as ever in his approach, was now claiming to be both an agnostic and a Roman Catholic.

- ↑ Dali, Salvador (1993) [original printing 1942]. The Secret Life of Salvador Dali. Dover. p. 395. ISBN 0-486-27454-3.

- ↑ McNeese, Tim (2006). Salvador Dali. Chelsea House. p. 102. ISBN 0-7910-8837-5.

- ↑ The Omega Point Theory - White Gardenia interview with Frank J. Tipler on the Omega Point Theory, December 2015 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kMkp1kZN5n4&t=26s

- ↑ National Gallery of Victoria Educational Resource

- ↑ Ocelot - Salvador Dali's pet - pictures and facts. Thewebsiteofeverything.com. Retrieved on 2014-05-12.

- ↑ Salvador Dali. Expert art authentication, certificates of authenticity and expert art appraisals - Art Experts. Artexpertswebsite.com. Retrieved on 2014-05-12.

- ↑ "Salvador Dali - The Mike Wallace interview - transcript". Harry Ransom Center. University of Texas at Austin. 1958-04-19. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ↑ "Dali on Whats my Line". retronaut.co. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ Frank, Priscilla (April 29, 2015). "The Early Days Of Television Were Way More Avant-Garde Than You Give Them Credit For". Retrieved June 26, 2017 – via Huff Post.

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑ [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3CmM19jBdrI&feature=youtu.be Salvador Dali on the Dick Cavett Show, Youtube

- ↑ "Dalí - Museu Berardo". en.museuberardo.pt. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Salvador Dali". www.academieroyale.be. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Major Retrospective Honors Dalí in Spain". The New York Times. April 19, 1983. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ↑ "The Salvador Dalí Online Exhibit". MicroVision. Retrieved June 13, 2006.

- 1 2 "Dalí picture sprung from jail". BBC. March 2, 2003.

- ↑ Sculpture is illustrated on page 144 N° 371 of the book by Robert & Nicolas Descharnes “Le Dur et le Mou”| Published by Editions ECCART, Paris, 2003, ISBN 978-2952102308