Alodia

| Alodia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th century–c. 1500 | |||||||||||

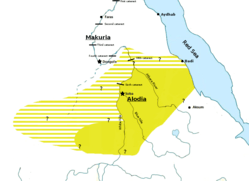

The approximate extension of Alodia in the 10th century. White beams and question marks symbolize uncertain ownership. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Soba | ||||||||||

| Common languages |

Nubian Greek (liturgical) Others[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Coptic Orthodox Christianity | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• First mentioned | 6th century | ||||||||||

• Destroyed | c. 1500 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||

Alodia, also known as Alwa (Greek: Aρογα, Aroua),[3] was a medieval Nubian kingdom in what is now central and southern Sudan. Its capital was the city of Soba located near modern-day Khartoum at the confluence of the Blue and White Nile.

Founded some time after the fall of the ancient kingdom of Kush in around 350, Alodia is first mentioned in historical records in 569. It converted to Coptic Christianity in 580, the last of the three Nubian kingdoms to convert, the other two being Nobadia and Makuria. The kingdom possibly reached its peak during the 9th–12th centuries when it is recorded to have controlled most of central and southern riverine Sudan including the Gezira as well as the Nuba mountains, the Butana and even parts of the desert bordering the Red Sea. It was described as being larger and mightier than its northern neighbor, Makuria, with which it maintained close dynastic ties.

From the 12th and especially the 13th century Alodia was declining possibly because of invasions from the south, droughts and a shift of trade routes. The 14th century saw the arrival of both the plague and bedouin tribes migrating into the upper Nile valley. By around 1500 Soba had fallen to either Arabs or the Funj, likely marking the end of Alodia, although some Sudanese oral traditions claimed that Alodia survived in the form of the kingdom of Fazughli within the Ethiopian-Sudanese borderlands. After the destruction of Soba, the Funj established the sultanate of Sennar ushering in a period of Islamization and arabization ultimately resulting in the modern day Sudanese Arab identity.

Sources

Alodia is by far the least studied of the three medieval Nubian kingdoms,[4] hence evidence is very slim.[5] What is known about it comes mostly from a handful of medieval historians from the Arabic world, most importantly al-Yaqubi (9th century), Ibn Hawqal and al-Aswani (both 10th century), who both visited the country in person, and Abu al-Makarim[6] (12th century).[7] The events around the Christianization of the kingdom in the 6th century have been described by the contemporary John of Ephesus,[8] while its fall is addressed in various post-medieval Sudanese sources.[9][10] Al-Aswani noted that he interacted with a Nubian historian who was "well-acquanted with the country of Alwa",[11] but no medieval Nubian historiographical work has been discovered yet.[12]

While many Alodian sites are known[13] it is only the capital Soba which received extensive excavations.[14] Parts of this site, which is approximately 2,75 km2 in size and is covered with numerous mounds of brick rubble previously belonging to monumental structures, have been unearthed in the early 1950s and again in the 1980s and 1990s.[15] The discoveries include several churches, a palace, cemeteries and numerous small finds.[16]

Geography

The Alodian heartland was the Gezira, a fertile plain bounded by the White and Blue Nile.[17] In contrast to the White Nile Valley the Blue Nile Valley is rich in known Alodian archaeological sites, among them Soba.[18] The extent of the Alodian influence to the south is unclear,[19] although it is likely that it bordered the Ethiopian highlands.[20] The southernmost Alodian sites have been noted in the proximity of Sennar.[lower-alpha 2]

To the west of the White Nile Ibn Hawqal differentiated between Al-Jeblien, which was controlled by Makuria and probably corresponded northern Kordofan, and the Alodian-controlled Al-Ahdin, which has been identified with the Nuba Mountains and perhaps extended as far south as Jebel al Liri, near the modern border to South Sudan.[23] Nubian connections with Darfur have been suggested, but evidence is lacking.[24]

The northern region of Alodia probably extended from the confluence of the two Niles downstream to Abu Hamad near Mograt Island.[25] Abu Hamad likely constituted the northern top of the Alodian province known as Al-Abwab ("the gates"),[26] although some scholars also suggest a more southern location, near the Atbara.[27] No evidence for a major Alodian settlement has been discovered north of the confluence of the two Niles yet.[28] Instead several forts have been recorded.[29]

Lying between the Nile and the Atbara was the Butana,[30] grassland suited for pastoralism.[25] Along the Atbara and the adjacent Gash Delta (near Kassala) many Christian sites have been noted.[31] The region around the Gash Delta was, according to Ibn Hawqal, governed by a vassal king loyal to Alodia.[32] The desert along the Red Sea was, as claimed by al-Aswani, also part of Alodia.[lower-alpha 3]

History

Origins

The name of Alodia might have been of considerable antiquity, perhaps appearing first as Alut on a Kushite stela from the late 4th century BC and again as Alwa in a list of Kushite towns by Pliny the Elder (1st century AD), said to be located south of Meroe.[34] In a 4th-century Aksumite inscription another town named Alwa is mentioned, albeit this time located near the confluence of the Nile and the Atbara.[35]

By the 4th century the kingdom of Kush, which used to control much of riverine Sudan, was in decline, and Nubians began to settle in the Nile Valley.[37] The Nubians originally lived west of the Nile but were forced eastwards due to changes in the climate, resulting in conflicts with Kush since at least the 1st century BC.[38] In the mid 4th century the Nubians had occupied most of the area once controlled by Kush,[35] while Kush itself was limited to the northern reaches of the Butana.[39] An Aksumite inscription mentions how the warlike Nubians also threatened the borders of the Aksumite kingdom north of the Tekeze River, resulting in an Aksumite expedition.[40] The inscription describes the Nubian defeat by the Aksumite forces and the subsequent march to the confluence of the Nile and Atbara, where the Aksumites plundered several Kushite towns, one of them the Alwa mentioned above.[35]

Archaeological evidence suggests that the kingdom of Kush ceased to exist still in the middle of the 4th century, albeit it remains unknown whether the Aksumite expeditions played a direct role in its fall. It seems likely that Aksumite presence in the Middle Nile Valley was short lived.[41] Eventually the region saw the development of regional centres whose ruling elites were buried in large tumuli.[42] Such tumuli within what would become Alodia are known from El-Hobagi, Jebel Qisi and maybe Jebel Aulia.[43] The excavated tumuli of El-Hobagi are known to date to the late 4th century[44] and contained an assortment of weaponry in imitation of Kushite royal funerary rituals.[45] Meanwhile, many Kushite sites, including the former capital Meroe, seem to have been largely abandoned.[46] The Kushites themselves were absorbed into the Nubians[47] and their language gave place to Nubian.[48]

How the kingdom of Alodia came into being is unknown.[49] Its formation was, however, completed by the mid 6th century, when it is attested to have existed alongside the two other Nubian kingdoms of Nobadia and Makuria in the north.[27] Soba, which by the 6th century had developed to a major urban center,[50] served as its capital.[27] In 569 the kingdom of Alodia was mentioned for the first time, being described by John of Ephesus as a kingdom on the cusp of Christianization.[49] Independently from John of Ephesus, the kingdom's existence is also verified by a late 6th century Greek document from Byzantine Egypt, describing the sell of an Alodian slave girl.[51]

Christianization and peak

.jpg)

The events around the Christianization of Alodia have been described by John of Ephesus in considerable detail. As the southernmost of the three Nubian kingdoms, Alodia was the last to be converted to Christianity. According to John, the Alodian king was aware of the baptism of Nobadia in 543 and eventually asked him to send him a bishop that would baptize his people as well. The request was granted in 580, leading to the baptism of the king, his family and the local nobility.[52] Thus Alodia became a part of the Christian world under the Coptic Patriarchate of Alexandria. After conversion, several pagan temples were probably converted into churches, like for example the temple in Musawwarat es-Sufra.[53] The extent and speed with which Christianity spread among the Alodian populace is, however, uncertain. Despite the conversion of the nobility, it is likely that Christianization of the rural population would have been proceeded slowly, or not at all.[54]

Roughly sixty years after the baptizing of the Alodian nobility, between 639 and 641, the Muslim Arabs conquered Egypt from the Byzantine Empire.[55] Makuria, which by this time had been unified with Nobadia,[56] fended off two subsequent Muslim invasions, one in 641/642 and another in 652. In the aftermath, both Makuria and the Arabs agreed to sign the Baqt, a peace treaty that also included a yearly exchange of gifts as well as other socio-economic regulations between Arabs and Nubians.[57] Alodia was mentioned in that treaty, explicitly referred to as not being affected by it.[58] While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia they began to settle along the western coast of the Red Sea, founding the port towns of Aydhab and Badi in the 7th century and Suakin, first mentioned in the 10th century.[59] From the 9th century they pushed further inland, settling among the Beja throughout the Eastern Desert. Their influence would remain confined to the east of the Nile until the 14th century.[60]

.jpg)

Based on archaeological evidence it has been suggested that Alodia's capital Soba underwent its peak of development between the 9th to 12th centuries.[61] In the 9th century Alodia was, albeit briefly, described for the first time by the Arab historian al-Yaqubi. In his short account Alodia is said to be the stronger of the two Nubian kingdoms, having a country requiring a three-month journey to cross it. He also recorded that Muslims would occasionally travel to there.[62]

A century later, in the mid 10th century, Alodia was visited by the traveller and historian Ibn Hawqal, resulting in the most comprehensive known account of the kingdom. He describes the geography and people of Alodia in considerable detail, giving the impression of a large, polyethnic state. He also notes its prosperity, having an "uninterrupted chain of villages and a continuous strip of cultivated lands".[63] When Ibn Hawqal arrived the ruling king was named Eusebius, who upon his death was succeeded by his nephew Stephanos.[64][65] Another Alodian king from this period was David, who is known from a Greek tombstone from Soba. His rule was initially dated to 999-1015, but based on palaeographical grounds it is now dated more broadly, to the 9th / 10th centuries.[66]

Ibn Hawqal's report concerning Alodia's geography was largely confirmed by al-Aswani, a Fatimid ambassador sent to Makuria, who would go on to travel to Alodia. Similar to what al-Yaqubi said 100 years before, Alodia was called more powerful than Makuria, being more extensive and having a larger army. The capital Soba was a prosperous town with "fine buildings, and extensive dwellings and churches full of gold and gardens", while also having a large Muslim quarter.[67]

Abu al-Makarim (12th century)[6] was the last historian to refer to Alodia in some detail. Alodia was still testified to be a large, Christian kingdom housing around 400 churches. A particularly large and finely constructed one was said to be located in Soba, called the "Church of Manbali".[68] Two Alodian kings, Basil and Paul, appear in 12th century Arabic letters from Qasr Ibrim.[65]

There is evidence that at certain periods there were close relations between the Alodian and the Makurian royal families, probably with the throne passing between the states after each king.[69] Nubiologist Włodzimierz Godlewski states that it was under the Makurian king Merkurios (early 8th century) when relations between the two kingdoms itensified.[70] In 943 it is written by al Masudi that the Makurian king ruled over Alodia, while Ibn Hawqal wrote that it was the other way around.[69] The 11th century saw the appearance of a new royal crown in Makurian art, which has been suggested to derive from the Alodian court.[71] King Mouses Georgios, who is known to have ruled in Makuria in the second half of the 12th century, most likely ruled both kingdoms via a personal union. Considering that in his royal title ("king of the Arouades and Makuritai") Alodia is mentioned before Makuria he might have initially been an Alodian king.[72]

Decline

Archaeological evidence from Soba suggests a decline of the town, and therefore possibly the Alodian kingdom, from the 12th century.[73] By c. 1300 the decline of Alodia had been well advanced.[74] Basically no pottery or glassware, neither native nor imported, postdating the 13th century could be identified at Soba.[75] Two churches were apparently destroyed during the 13th century, although they were later rebuilt.[76] It has been suggested that Alodia was under attack of an African, possibly Nilotic[77] people called Damadim who originated from the border region of modern Sudan and South Sudan, along the Bahr al Ghazal,[78] who, according to Al-Maghrebi, attacked Nubia in the year 1220.[79] Soba may have been conquered at this time, suffering occupation and destruction.[78] In the late 13th century another invasion by an unspecified people from the south occurred.[80] In the same period al-Harrani wrote that Alodia's capital was now called Waylula,[74] described as "very large" and "built on the west bank of the Nile".[81] In the early 14th century al-Dimashqi wrote that the capital was a place named Kusha, located far away from the Nile where water had to be obtained from wells.[82]

Economic factors also seem to have played a part in Alodia's decline. From the 10th to 12th centuries the East African coast saw the rise of new trading cities (like for example Kilwa), which, since they exported similar goods to Nubia, were direct mercantile competitors.[83] A period of severe droughts occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa between 1150 and 1500 would have affected the Nubian economy as well.[84] Archaeobotanical evidence from Soba suggests that the town suffered from overgrazing and overcultivation.[85]

By 1276 Al-Abwab, previously described as the northermost Alodian province, was recorded as an independent splinter kingdom ruling over vast territories. The precise circumstances of its secession and relations with Alodia thereafter remain unknown.[86] In 1286 a Mamluke prince sent messengers to several rulers in central Sudan. It is not clear if they were still subject to the king in Soba[87] or if they were independent, implying a fragmentation of Alodia into multiple petty states by the late 13th century.[74] In 1317 a Mamluk expedition pursued Arab brigands as far south as Kassala in Taka (one of the regions which received a Mamluk messenger in 1286[87]), marching through Al-Abwab and Makuria on their way back.[88]

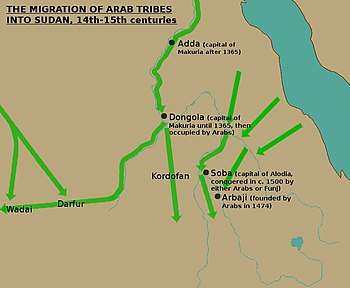

During the 14th and 15th centuries much of what is now Sudan was eventually overran by bedouin tribes,[89] who perhaps profited from the plague which in the mid 14th century might have ravaged in Nubia and killed many sedentary Nubians, but did not affect the Arabic nomads.[90] The Arabs would have then intermixed with the remaining local population, gradually taking control over land and people,[91] greatly benefiting from their large population in spreading their culture.[92] The first recorded Arab migration to Nubia dates to 1324,[93] but it was the disintegration of Makuria in the late 14th century that caused the "flood gates" to "burst wide open".[94] Many, initially coming from Egypt, followed the course of the Nile until they reached Al Dabbah, where they parted west to migrate along the Wadi Al-Malik to reach Darfur or Kordofan.[95] Alodia, in particular the Butana and the Gezira, was the target of those Arabs who had lived among the Beja[96] in the Eastern Desert for centuries.[97]

Initially, the kingdom was able to enforce authority over some of the newly arrived Arab groups, forcing them to pay tribute, but the situation grew increasingly more precarious the more new bedouins arrived.[98] By the second half of the 15th century the Arabs had settled in the entire central Sudanese Nile valley except for the area around Soba,[91] which was all that was left of Alodia's domain.[99] In 1474[100] it was recorded that the Arabs founded the town of Arbaji on the Blue Nile, which would quickly develop into an important center of commerce and Islamic learning.[101] In around 1500 it was recorded that the Nubians were in a state of total political fragmentation, with 150 lordships residing on both sides of the Nile.[74] Archaeology attests that Soba was largely ruined at this time.[9]

Fall

It is not clear if the kingdom of Alodia was destroyed by either the Arabs under Abdallah Jammah or the Funj, an African group from the south which was led by their king Amara Dunqas.[9] However, most modern scholars tend to agree with the Arab narrative.[102][103]

Abdallah Jammah ("Abdallah the gatherer"), the eponymous ancestor[104] of the Sudanese Abdallab tribe, was a Rufa'a[105] Arab who, according to Sudanese traditions, settled in the Nile Valley after coming from the east. He consolidated his power and established his capital at Qerri, just north of the confluence of the two Niles.[106] In the late 15th century he gathered the Arabic tribes to act against the, as it is called, Alodian "tyranny", which has been interpreted as a religious-economic motive, i.e. the Muslim Arabs no longer accepted the rule of, nor taxation by, a Christian ruler. Under his leadership Alodia and its capital Soba were destroyed,[107] resulting in rich booty like a "bejeweled crown" and a "famous necklace of pearls and rubies".[106]

According to another tradition, recorded in old documents from Shendi, Soba was destroyed by Abdallah Jammah in 1509 after already getting attacked in 1474. The idea to unite the Arabs against Alodia is said to have already come to mind to an Emir who lived between 1439 and 1459. For this purposes he migrated from Bara in Kordofan to a mountain near Ed Dueim at the White Nile. Under his grandson, called Emir Humaydan, the White Nile was crossed, where he met with other Arab tribes, and attacked Alodia. The king of Alodia was killed, but the "patriarch", probably the archbishop of Soba, managed to flee. Soon, however, he returned to Soba, a puppet king was crowned and an army of Nubians, Beja and Abyssinians was assembled to fight "for the sake of religion". Meanwhile, the Arab alliance was about to fracture, but Abdallah Jammah reunited them while also allying with the Funj king Amara Dunqas. Together they finally defeated and killed the patriarch, razing Soba afterwards and enslaving its population.[108]

The "Funj chronicle", a history of the Funj Sultanate that was compiled in the 19th century, ascribes the destruction of Alodia to king Amara Dunqas, albeit he was also allied with Abdallah Jammah.[103] This attack is dated to the 9th century after the Hijra (c. 1396–1494). Afterwards Soba is said to have served as the capital of the Funj until the foundation of Sennar in 1504.[109] The "Tabaqat Dayfallah", a history of Sufism in Sudan (c. 1700), briefly mentions that the Funj attacked and defeated the "kingdom of the Nuba" in 1504-1505.[110]

Legacy

Historian Jay Spaulding proposes that the fall of Soba was not necessarily the end of Alodia. According to the Jewish traveller David Reubeni, who visited the country in 1523, there was still a "kingdom of Soba" on the eastern bank of the Blue Nile, albeit he also explicitly noted that Soba itself was in ruins. This would match with oral traditions from the upper Blue Nile, claiming that Alodia survived Soba's fall and was still existing along the Blue Nile, albeit it gradually retreated to the mountains of Fazughli in the Ethiopian-Sudanese borderlands, forming the kingdom of Fazughli.[111] Recent excavations in western Ethiopia seem to confirm the theory of an Alodian migration.[112] The Funj eventually conquered Fazughli in 1685 and its habitants, known as Hamaj, became a fundamental part of Sennar and eventually even seized power in 1761-1762.[113] As recently as 1930[104] Hamaj villagers in the southern Gezira would swear by "Soba the home of my grandfathers and grandmothers which can make the stone float and the cotton ball sink.", an oath they did not dare to break.[87]

In 1504-1505 the Funj founded the Funj sultanate, incorporating Abdallah Jammah's domain, which, according to some traditions, happened after a battle where Amara Dunqas defeated Abdallah Jammah.[114] The Funj maintained some medieval Nubian customs like the wearing of crowns with features resembling bovine horns, called taqiya umm qarnein,[115] the shaving of the head of a king upon his coronation,[116] or, according to Jay Spaulding, the custom of raising princes separatedly from their mothers, under strict confinement.[117]

The aftermath of Alodia's fall saw extensive arabization, with the Nubians embracing the tribal system of the Arab migrants.[118] Those living along the Nile between Al Dabbah in the north and the confluence of the two Niles in the south got subsumed into the Ja'alin tribe,[119] while east, west and south of the Ja'alin the country is now dominated by tribes claiming a Juhaynah ancestry.[120] In the area around Soba prevailed the tribal Abdallab identity.[121] The Nubian language remained spoken in central Sudan until the 19th century, when it finally got replaced by Arabic,[122] albeit many words of Nubian origin[123] and Nubian place names as far south as the Blue Nile state were preserved.[124]

The fate of Christianity in the region remains largely unknown.[125] The church institutions would have collapsed together with the fall of the kingdom,[118] resulting in the decline of the Christian faith and the rise of Islam in its stead.[126] Islamized groups from northern Nubia began to proselytize the Gezira[127] and as early as 1523 Amara Dunqas, who was initially a pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim.[128] Nevertheless, in the 16th century large portions of the Nubians would still have regarded themselves as Christians.[129] A traveller who visited Nubia around 1500 stated that the Nubians considered themselves Christian but were so lacking in Christian instruction that they had no actual knowledge of the faith.[130] In 1520 Nubian ambassadors reached Ethiopia and petitioned the emperor for priests, claiming that no more priests could reach Nubia because of the wars between Muslims, leading to a decline of Christianity in their land.[131] In the 17th century a church in the Nuba mountains was mentioned by a Sudanese prophecy.[132] As late as the early 1770s there was said to be a Christian princedom in the Ethiopian-Sudanese border area, called Shaira.[133] Certain apotropaic rituals stemming from Christian practices remained in use until well into the 20th century.[134] Such rituals, often including crosses and resembling christenings, have been recorded in the Gezira,[135][87] Fazughli,[87] Kordofan, the Nuba mountains and even Darfur.[136]

Soba, which remained inhabited until at least the early 17th century,[137] served, among many other ruined Alodian sites, as steady supply of bricks and stones for nearby built Qubba shrines dedicated to Sufi holymen.[138] During the early 19th century many of the remaining bricks in Soba were plundered for the construction of Khartoum, the new capital of the recently colonized Sudan.[139]

Administration

Information on the organization of Alodia is sparse,[140] but it is probable that its organization was similar to that of Makuria.[141] The head of state was the king who, according to al-Aswani, reigned as an absolute monarch[140] and was able to enslave any of his subjects without further reason. The people did not oppose him, but prostrated themselves before him.[142] As in Makuria the succession to the Alodian throne was matrilineal, that is, it was the son of the king's sister and not the king's son who succeeded to the throne.[141] There might be evidence that there existed a mobile royal encampment, although the translation of the original source, Abu al-Makarim, is not certain.[143] Similar mobile courts are known to have existed in the early Funj sultanate, Ethiopia and Darfur.[144]

The kingdom was divided into several provinces under the sovereignty of Soba.[145] It seems that these provinces were governed by delegates of the king:[140] al-Aswani stated that the governor of the northern Al-Abwab province was appointed by the king,[146] while similarly was also recorded by Ibn Hawqal for the Gash Delta region, which was ruled by an appointed arabophone.[32] In 1286 Mamluk emissaries were sent to several ruler in central Sudan. It is not clear if those rulers were actually independent,[74] which in the case of the "Sahib" of Al-Abwab, who is named first in the list,[87] seems certain,[86] or if they were still subordinated to the king of Alodia. If the latter is the case this would provide an understanding of the territorial organization of the kingdom. Apart of Al-Abwab following regions are mentioned: Al-Anag (possibly Fazughli); Ari; Barah; Befal; Danfou; Kedru (possibly after Kadero, a village north of Khartoum); Kersa (the Gezira); and Taka (the region around the Gash Delta).[147]

State and church were closely interwined in Alodia,[148] with the Alodian kings probably serving as its patrons.[149] Coptic documents observed by Johann Michael Vansleb during the later 17th century list the following bishoprics in the Alodian kingdom: Arodias; Borra; Gargara; Martin; Banazi; and Menkesa.[150] Arodias might have referred to the bishopric in Soba.[148]

Alodia may have had a standing army[147] in which cavalry probably played an important role in force projection and as a symbol of royal authority deep into the provinces.[151] Due to their speed, horses were also important for communications, providing a rapid courier service from the capital to the provinces.[151] Aside from horses, boats would have also played a central role in the transport infrastructure.[152]

Culture

Languages

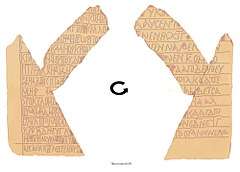

The kingdom of Alodia was a polyethnic and hence polylingual,[153] but still essentially Nubian state with a Nubian language being spoken by the majority.[154] Based on the limited evidence available it has been proposed that the Alodian Nubian language was different from that of northern Nubia, Old Nobiin,[155] albeit still closely related.[156] This language was, as was the case in Makuria, written in a variant of the Coptic alphabet. Despite a lack of in-depth study in this area it is known that there were differences between the Old Nubian and Alodian alphabets. Erman, who studied several Alodian inscriptions, suggested that the Alodian script had five unique letters,[156] while Monneret de Villard believed that it had six.[157] The latter also assumes that those letters derived from Meroitic letters.[157]

Apart from Nubian, Greek also played an important role. Greek was considered a prestigious sacral language, albeit it does not seem to have actually been spoken.[158] An example of the use of Greek in Alodia is the tombstone of King David, where it is written with surprisingly accurate grammar.[159] Al-Aswani noted that books in Alodia were written in Greek, which were then translated into Nubian.[67] Coptic was probably used to communicate with the Patriarch of Alexandria,[141] but Coptic written remains are very sparse.[160]

In total, only around 5% of all known written records of Christian Nubia come from Alodia, although this can be mostly attributed to the uneven distribution of excavations.[161]

A multitude of other languages except of Nile Nubian were spoken throughout the kingdom. In the Nuba mountains Nubian dialects known as Hill Nubian occurred together with various Kordofanian languages. Upstream the Blue Nile Eastern Sudanic languages like Berta or Gumuz were spoken. In the eastern territories lived, apart of the Semitic Tigre[2] the Beja, who spoke their own Kushitic language, as well as the Arabs.[1]

Architecture

Churches and residences

Al-Aswani stated that the churches in Soba were "rich with gold and gardens",[162] while Abu Salih wrote of a "very large and spacious church, skillfully planned and constructed, and larger than all the other churches in the country; it is called the church of Manbali".[163] According to him, Alodia as a whole was home to 400 churches,[163] of which seven have been identified so far, and given the simple names of "Church A", "Church B", "Church C", "Church E", the "mound C" church in Soba, the church in Saqadi, and the temple-church in Musawwarat as-Sufra.[164] Churches "A", "B" and "C", along with a residential Building "D", formed a standalone complex. It was a multi-storied mud brick building with at least two levels,[165] within which were found the remains of painted wall plaster fragments, probably dating to the 9th–12th century and bearing stylistic similarities with murals from Makuria.[166] The scale of the structure is suggestive of a palatial estate, possibly the residence of the bishop of Soba, or perhaps the king of Alodia.[167] Churches "A" and "B" were probably built in the mid 8th century.[168] The church of Musawwarat es-Sufra, called "Temple III A", was initially a pagan temple but was converted into a church, probably soon after the royal conversion in 580.[169] It was a small, rectangular building with four rooms.[170] The roof, of an indeterminate shape, was supported by wooden beams.[171] Despite originally being a Kushite temple it still bears similarities to purpose built churches, for example having an entrance on both the north and south side.[172] Overall, Alodian church architecture differed to that employed in Medieval Ethiopia, but instead bore certain similarities to churches in Armenia.[173] Furthermore, Alodian churches utilized more wood than those in Makuria.[174]

- Gallery

Ground plan of the same church.

Ground plan of the same church. A capital, part of the same church.

A capital, part of the same church. Church complex of "Mound B", Soba.

Church complex of "Mound B", Soba. "Temple 3 A", Musawwarat as-Sufra.

"Temple 3 A", Musawwarat as-Sufra.

Domestic architecture

At Soba, the remains of circular timber structures have been discovered, probably belonging to huts.[175] Such timber huts, both circular and rectangular in shape, were perhaps the most common type of domestic architecture in Alodia.[176] Other types of domiciles may have been similar to those used today, from simple huts of matting over walls constructed with rammed earth to rectangular, brick-walled houses with flat, rain-proof roofs made of palm and mud plastering.[177]

Fortresses

Not many fortresses are known and their chronology is often uncertain.[178] During the early Middle Ages, Meroitic fortresses were reoccupied and their walls restored.[179] Only a few fortresses were apparently built from scratch, two from the late Middle Ages are known: Jebel Irau and Fangool.[180]

Pottery

In Medieval Nubia, pottery and its decoration was appreciated as an art form.[181] Until the 7th century the most common pottery type found at Soba was the so-called "Red Ware". These wheel-made hemispherical bowls were made of red or orange slip and were painted with separated motifs such as boxes with inner cross-hatchings, stylized floral motifs or crosses. The outlines were drawn in black while the fillings were white. In their design, they are a direct continuation of Meroitic styles, with possible influences from Aksumite Ethiopia. Due to their relative rarity it has been suggested that they were imported, although they bear similarities to the pottery type, known as "Soba Ware", that succeeded them.[182]

"Soba Ware" was a type of wheel-made pottery with a distinctive decoration very different from the rest of Nubia.[183][184] The shape of the pottery was diverse, as was the repertoire of painted decoration. One of the most distinctive features was the usage of faces as painted decoration. They were simplified, if not geometric in form and with big round eyes. This style is foreign to Makuria and Egypt, but bears a resemblance to paintings and manuscripts from Ethiopia.[185] It is possible that the potters copied these motifs from local church murals.[186] Also unique was the application of animal-shaped bosses (protomes).[187] Glazed vessels were also produced, copying Persian aquamaniles without reaching their quality.[188] Beginning in the 9th century, "Soba Ware" was increasingly replaced by fine ware imported from Makuria.[166]

Economy

Agriculture

Alodia was located in the savannah belt, giving it an economic advantage over its northern neighbour Makuria.[4] North of the confluence of the Blue and White Nile agriculture was mostly limited to the Nile valley, with the irrigation of the farms provided using devices like the shadoof or the more complex sakia,[189] but south of the confluence there was sufficient rainfall, with the amount increasing to the south.[190] Al-Aswani noted that "the provisions of the country of Alwa and their king" came from Kersa, which has been identified with the Gezira.[145]

Archaeological records have provided insight into the types of food grown and consumed in Alodia. In Soba, the primary cereal was sorghum, although barley and millet were also known to be consumed.[191] Al-Aswani noted that sorghum was used to make beer,[162] and also stated that vineyards were quite rare in Alodia compared to Makuria.[162] This has been explained by the climate of the Gezira being unsuited for the cultivation of grapes; however, sizable amounts of grapes have been found at Soba.[192] According to al-Idrisi, Alodian farmers also cultivated onions, horseradish, cucumbers, watermelons and rapeseed,[193] but none of them have been identified at Soba.[194] Instead, there were found figs, acacia fruits, dom palm fruits and dates.[195]

As well as horticulture, animal husbandry would have been crucial to the Alodian diet, much as it was during Meroitic times.[196] Al-Aswani wrote that beef was plentiful, which was attributed to the bountiful grazing land.[142] This is corroborated by evidence discovered at Soba.[197] The fecundity of the plains would have granted pastoralists the ability to raise a variety of animals.[196] Ibn Hawqal noted that the inhabitants of Taflien bred camels as well as cattle.[198] In addition to cattle, chickens,[199] sheep and goats all had a place in the Alodian diet. The proportion of sheep (87%) and goat (13%) remains from Soba suggest that sheep were bred mostly for their meat, while goats were bred for their milk.[200] Al Aswani mentioned how the king of Alodia possessed "tawny camels of Arabian pedigree",[142] but archaeology does not imply wide-ranging consumption as the remains of only three individuals could be determined at Soba none of which bore signs of butchery.[201] No remains of pigs have been identified,[199] and fish was determined only to be complementary to the overall diet of Soba.[197]

Trade

Network

Camel caravans played a critical role in maintaining the trade network that connected Alodia with Makuria, Egypt, the Red Sea ports and, as attested to by Benjamin of Tudela, Kordofan, Darfur and even Zuwila, an important trading town in Fezzan.[202] Archaeological evidence of South Arabian, Indian and Chinese goods has been discovered in Alodian territories,[203] probably entering Sudan from the Red Sea ports.[204] These trading contacts with the outside world were predominantly via Arab merchants.[205] Muslim merchants roamed Nubia, with some living in a district in Soba.[206] Imports from Makuria were not common.[207] The extent of the trading relations with Christian Ethiopia is uncertain. John of Ephesus wrote of Aksumites in Alodia, which may have referred to merchants,[208] while Cosmas Indicopleustes reported Aksumite trade expeditions into the Blue Nile Valley;[209] at Aksum, two shards of Soba Ware, a characteristic Alodian pottery, have been identified.[210] A later source, al-Idrisi, made mention of a trading town in the northern Butana, a place "where merchants from Nubia and Ethiopia gather together with those from Egypt".[209] There are some Ethiopian traditions that recall a people named "Soba Noba".[211] Historian Mordechai Abir suggests that merchants from the Zagwe kingdom travelled through Alodia to reach Egypt.[212] However, the few artefacts discovered so far suggest only very limited trading relations, and contact in general.[213]

Exports and imports

Exports from Alodia likely included raw materials such as gold, ivory, salt and other tropical products.[214] It is also commonly assumed that slaves were exported from Nubia. Archaeologist William Y. Adams believes that Alodia was a specialized slave-trading state that would have exploited the pagan populations to the west and south.[215] The African slave armies that were deployed in Egypt by the Tulunids, Ikhshidids and Fatimids are often quoted as evidence for a Nubian slave trade, but it is more likely that these slaves came from the Chad basin instead (in Fatimid sources they appear as Zuwayla, indicting an origin from Zawila, Fezzan).[216] However, there is little evidence of a regulated medieval Nubian slave-trade.[217] It is only from the 16th century, after the decline of the Nubian kingdoms, that sources described a developing slave trade.[218]

At Soba, both silk and flax have been found, most probably imported from Egypt,[219] as well as beads made of faience and glass,[220] which seemed to be particular popular.[76]

King list

| Name | Date of rule | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Giorgios | ? | Recorded on an inscription from Soba.[65] |

| David | 9th or 10th century | Recorded on his tombstone from Soba. Initially thought to have ruled from 999–1015, but now proposed to have lived in the 9th / 10th centuries.[66] |

| Eusebios | ca. 938–955 | Mentioned by Ibn Hawqal.[65][221] |

| Stephanos | ca. 955 | Mentioned by Ibn Hawqal.[65][221] |

| Mouses Georgios | c. 1155-1190 | Joint ruler of Makuria and Alodia. Recorded on letters from Qasr Ibrim and a graffito from Faras.[72] |

| ?Basil | 12th century | Recorded on an Arabic letter from Qasr Ibrim.[65] |

| ?Paul | 12th century | Recorded on an Arabic letter from Qasr Ibrim.[65] |

Annotations

- ↑ Kordofanian; various Eastern Sudanic languages spoken in the Upper Blue Nile Valley like Berta; Beja; Arabic[1] and Tigre[2]

- ↑ "The most southerly church known, which presumably was within the kingdom of Alwa, lay at Saqadi 50 km to the west of Sennar",[21] while "the most southerly find of Alwan material on the Blue Nile is a pottery chalice, from Khalil el-Kubra 40 km upstream of Sennar."[22]

- ↑ "The Beja of the interior, who live in the desert of the country of 'Alwa along the [Red] Sea up to the frontier of Ethiopia..."[33]

Notes

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, pp. 89-90.

- 1 2 Zaborski 2003, p. 471.

- ↑ Lajtar 2009, p. 93.

- 1 2 Welsby 2014, p. 183.

- ↑ Welsby 2014, p. 197.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 93.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 15-23.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 12-15.

- 1 2 3 Welsby 2002, p. 255.

- ↑ Vantini 2006, pp. 487-491.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 9.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 58-70.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 25.

- ↑ Edwards 2004, p. 221.

- ↑ Werner 2013, pp. 161-164.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 41.

- ↑ Welsby 2014, Figure 2.

- ↑ Obluski 2017, p. 15.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 8.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 86.

- ↑ Welsby 2014, p. 185.

- ↑ Spaulding 1998, p. 49.

- ↑ Edwards 2004, p. 253.

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, p. 74.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 21–22.

- 1 2 3 Welsby 2002, p. 26.

- ↑ Welsby 2014, p. 192.

- ↑ Welsby 2014, pp. 188-190.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 62.

- ↑ Welsby 2014, p. 187.

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, p. 98.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, p. 630.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Hatke 2013, §4.5.2.3.

- ↑ Rilly 2008, Fig. 3.

- ↑ Rilly 2008, p. 211.

- ↑ Rilly 2008, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 35.

- ↑ Hatke 2013, §4.5.2.1., see also §4.5. for the discussion of a Greek inscription with similar content.

- ↑ Hatke 2013, §4.6.3.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Welsby 2014, p. 191.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 28.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Edwards 2004, p. 187.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 39.

- ↑ Edwards 2004, p. 182.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ Welsby 1998, p. 20.

- ↑ Pierce 1995, pp. 148-166.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, pp. 32-34.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 62.

- ↑ Edwards 2001, p. 95.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 68.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 77.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, pp. 68-71.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 77.

- ↑ Power 2008.

- ↑ Adams 1977, pp. 553-554.

- ↑ Shinnie 1961, p. 76.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Welsby 2002, p. 261.

- 1 2 Lajtar 2003, p. 203.

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, p. 20.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 22-23.

- 1 2 Welsby 2002, p. 89.

- ↑ Godlewski 2012, p. 204.

- ↑ Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 184.

- 1 2 Lajtar 2009, pp. 89-94.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 252.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 19.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 34.

- 1 2 Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 9.

- ↑ Beswick 2004, p. 24.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 115.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, p. 400.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, p. 130.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, p. 448.

- ↑ Adams 1977, pp. 537-538.

- ↑ Grajetzki 2009, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Zurawski 2014, p. 84.

- ↑ Cartwright 1999, p. 256.

- 1 2 Welsby 2002, p. 254.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zarroug 1991, p. 99.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 138.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, p. 176.

- ↑ Werner 2013, pp. 142–143.

- 1 2 Hasan 1967, p. 128.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, p. 175.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, p. 106.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 556.

- ↑ Braukämper 1992, pp. 108–109, 111.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, p. 145.

- ↑ Adams, p. 554.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, pp. 129&132–133.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 545.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, p. 784.

- ↑ McHugh 1994, p. 38.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 25.

- 1 2 Adams 1977, p. 538.

- 1 2 Adams 1977, p. 539.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, p. 132.

- 1 2 O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 23.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Vantini 2006, pp. 487–491.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, pp. 786-787.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, pp. 784-785.

- ↑ Spaulding 1974, pp. 12-21.

- ↑ Gonzalez-Ruibal & Falquina 2017, pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Spaulding 1974, pp. 21-25.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Zurawski 2014, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Zurawski 2014, p. 149.

- ↑ Spaulding 1985, p. 23.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 156.

- ↑ Adams 1977, pp. 557–558.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 558.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 29.

- ↑ Edwards 2004, p. 260.

- ↑ Abu-Manga 2009, p. 377.

- ↑ Taha 2012, p. 10 (Taha ascribes these names a Dongolawi Nubian origin).

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 171.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 564.

- ↑ McHugh 1994, p. 59.

- ↑ Werner 2013, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Zurawski 2014, pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 150.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 181.

- ↑ Spaulding 1974, p. 22, note 31.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 177.

- ↑ Werner 2013, pp. 177–178.

- ↑ Werner 2013, pp. 181–184.

- ↑ Crawford 1951, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ McHugh 2016, p. 110.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Zarroug 1991, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Obluski 2017, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Vantini 1975, p. 614.

- ↑ Seignobos 2015, p. 224.

- ↑ Spaulding 1972, p. 52.

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, p. 100.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 19.

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, pp. 98–100.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 165.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 101.

- ↑ Crawford 1951, p. 26.

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, p. 22.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 85.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 88-90.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 46.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 29-30.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 186, note 6.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 188, note 23.

- ↑ Ochala 2014, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, pp. 274–276.

- ↑ Ochala 2014, p. 37.

- ↑ Ochala 2014, pp. 22–23.

- 1 2 3 Vantini 1975, p. 613.

- 1 2 Vantini 1975, p. 326.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 149, note 38.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 317.

- 1 2 Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 183.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 318.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 163.

- ↑ Török 1974, p. 100.

- ↑ Török 1974, p. 74.

- ↑ Török 1974, p. 95.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 154.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 322.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 164.

- ↑ Welsby 1998, p. 269.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 166.

- ↑ Shinnie 1961, p. 78.

- ↑ Drzewiecki 2016, p. 16.

- ↑ Drzewiecki 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Drzewiecki 2016, p. 47.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 194.

- ↑ Danys & Zielinska 2017, pp. 177–178.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 234.

- ↑ Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 182.

- ↑ Danys & Zielinska 2017, pp. 179–181.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 235.

- ↑ Danys & Zielinska 2017, p. 180.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 77-79.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. ??.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, pp. 265–267.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels1991, p. 271.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, p. 274.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 273.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, Table 16.

- 1 2 Zarroug 1991, p. 82.

- 1 2 Welsby 1998, p. 245.

- ↑ Vantini 1975, p. 164.

- 1 2 Welsby 2002, p. 187.

- ↑ Welsby 1998, p. 236.

- ↑ Welsby 1998, p. 240.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, pp. 85–87, Map X.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 87.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 50.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 86.

- ↑ Hasan 1967, p. 46.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 334.

- ↑ Hatke 2013, §5.3.

- 1 2 Welsby 2002, p. 215.

- ↑ Hatke 2013, §5.1.

- ↑ Brita 2014, p. 517.

- ↑ Abir 1980, p. 15.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ Zarroug 1991, p. 84.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 471.

- ↑ Edwards 2011, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Edwards 2011, p. 103.

- ↑ Edwards 2011, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 307.

- ↑ Welsby & Daniels 1991, p. 159.

- 1 2 Vantini 1975, p. 153.

References

- Abir, Mordechai (1980). Ethiopia and the Red Sea: The Rise and Decline of the Solomonic Dynasty and Muslim European Rivalry in the Region. Routledge. ISBN 0714631647.

- Abu-Manga, Al-Amin (2009). "Sudan". In Kees Versteegh. Encyclopedia of Arabic Languages and Linguistics. Volume IV. Q-Z. Brill. pp. 367–375. ISBN 9004177027.

- Adams, William Y. (1977). Nubia. Corridor to Africa. Princeton University. ISBN 0691093709.

- Beswick, Stephanie (2004). Sudan's Blood Memory. University of Rochester. ISBN 1580462316.

- Braukämper, Ulrich (1992). Migration und ethnischer Wandel. Untersuchungen aus der östlichen Sahelzone ["Migration and ethnic change. Investigations from the eastern Sahel zone"] (in German). Franz Steiner. ISBN 3515058303.

- Brita, Antonella (2014). "Soba Noba". In Siegbert Uhlig, Alessandro Bausi. Encyclopedia Aethiopica. 5. Harrassowitz. p. 517. ISBN 9783447067409.

- Cartwright, Caroline R. (1999). "Reconstructing the Woody Resources of the Medieval Kingdom of Alwa, Sudan". In Marijke van der Veen. The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa. Kluwer Academic/Plenum. pp. 241–259. ISBN 9781475767308.

- Crawford, O. G. S. (1951). The Fung Kingdom of Sennar. John Bellows LTD. OCLC 253111091.

- Danys, Katarzyna; Zielinska, Dobrochna (2017). "Alwan art. Towards an insight into the aesthetics of the Kingdom of Alwa through the painted pottery decoration". Sudan&Nubia. Sudan Archaeological Research Society. 21: 177–185. ISSN 1369-5770.

- Drzewiecki, Mariusz (2016). Mighty Kingdoms and their Forts. The Role of Fortified Sites in the Fall of Meroe and Rise of Medieval Realms in Upper Nubia. IKSiO PAN. ISBN 9788394357085.

- Edwards, David (2001). "The Christianisation of Nubia: Some archaeological pointers". Sudan & Nubia. The Sudan Archaeological Research Society. 5: 89–96. ISSN 1369-5770.

- Edwards, David (2004). The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan. Routledge. ISBN 0415369878.

- Edwards, David (2011). "Slavery and Slaving in the Medieval and Post-Medieval kingdoms of the Middle Nile". In Paul Lane and Kevin C. MacDonald. Comparative Dimensions of Slavery in Africa: Archaeology and Memory. British Academy. pp. 79–108. ISBN 0197264786.

- Gonzalez-Ruibal, Alfredo; Falquina, Alvaro (2017). "In Sudan's Eastern Borderland: Frontier Societies of the Qwara Region (ca. AD 600-1850)". Journal of African Archaeology. Brill. 15 (2): 173–201. doi:10.1163/21915784-12340011. ISSN 1612-1651. Archived from the original on 2018-09-14.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2009). "Das Ende der christlich-nubischen Reiche ["The end of the Christian Nubian realms"]" (PDF). Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie (in German). Golden House Publications. X. ISBN 978-1-906137-13-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-19.

- Godlewski, Wlodzimierz (2012). "Merkurious". In Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong, Steven J. Niven. Dictionary of African Biography. 4. Oxford University. p. 204. ISBN 9780195382075.

- Hasan, Yusuf Fadl (1967). The Arabs and the Sudan. From the seventh to the early sixteenth century. Edinburgh University. OCLC 33206034.

- Hatke, G. (2013). Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa. NYU. ISBN 9780814760666.

- Hesse, Gerhard (2002). Die Jallaba und die Nuba Nordkordofans. Händler, Soziale Distinktion und Sudanisierung ["The Jallaba and the Nuba of northern Kordofan. Traders, social distinction and Sudanization"] (in German). Lit. ISBN 3825858901.

- Lajtar, Adam (2003). Catalogue of the Greek Inscriptions in the Sudan National Museum at Khartoum. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1252-6.

- Lajtar, Adam (2009). "Varia Nubica XII-XIX" (PDF). The Journal of Juristic Papyrology (in German). XXXIX: 83–119. ISSN 0075-4277. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-25.

- McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan. Northwestern University. ISBN 0810110695.

- McHugh, Neil (2016). "Historical perspectives on the domed shrine in the Nilotic Sudan". In Abdelmajid Hannoum. Practicing Sufism: Sufi Politics and Performance in Africa. Routledge. pp. 105–130. ISBN 113864918X.

- Obluski, Artur (2017). "Alwa". In Saheed Aderinto. African Kingdoms: An Encyclopedia of Empires and Civilizations. ABC-CLIO. pp. 15–17. ISBN 9781610695800.

- Ochala, Grzegorz (2014). "Multilingualism in Christian Nubia: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches". Dotawo: A Journal for Nubian Studies. Journal of Juristic Papyrology. 1. ISBN 0692229140.

- O'Fahey, R.S.; Spaulding, Jay L. (1974). Kingdoms of the Sudan. Methuen Young Books. ISBN 0416774504.

- Pierce, Richard Holton (1995). "A sale of an Alodian slave girl: A reexamination of papyrus Strassburg Inv. 1404". Symbolae Osloenses. Taylor & Francis. LXX: 148–166. ISSN 0039-7679.

- Power, Tim (2008). "The Origin and Development of the Sudanese Ports ('Aydhâb, Bâ/di', Sawâkin) in the early Islamic Period". Chroniques yéménites. Centre français d’archéologie et de sciences sociales de Sanaa. 15: 92–110. ISSN 1248-0568.

- Rilly, Claude (2008). "Enemy brothers: Kinship and relationship between Meroites and Nubians (Noba)". Between the Cataracts: Proceedings of the 11th Conference of Nubian Studies, Warsaw, 27 August- 2 September 2006. Part One. PAM. pp. 211–225. ISBN 978-83-235-0271-5. Archived from the original on 2018-05-05.

- Seignobos, Robin (2015). "Les évêches Nubiens: Nouveaux témoinages. La source de la liste de Vansleb et deux autres textes méconnus". In Adam Lajtar, Grzegorz Ochala, Jacques van der Vliet. Nubian Voices II. New Texts and Studies on Christian Nubian Culture (in French). Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation. ISBN 8393842573. Archived from the original on 2018-09-29.

- Shinnie, P. (1961). Excavations at Soba. Sudan Antiquities Service. OCLC 934919402.

- Spaulding, Jay (1972). "The Funj: A Reconsideration". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University. 13 (1): 39–53. ISSN 0021-8537.

- Spaulding, Jay (1974). "The Fate of Alodia" (PDF). Meroitic Newsletter. Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 15: 12–30. ISSN 1266-1635. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-19.

- Spaulding, Jay (1985). The Heroic Age in Sennar. Red Sea. ISBN 1569022607.

- Spaulding, Jay (1998). "Early Kordofan". In Endre Stiansen and Michael Kevane. Kordofan Invaded: Peripheral Incorporation in Islamic Africa. Brill. pp. 46–59. ISBN 9004110496.

- Taha, A. Taha (2012). "The influence of Dongolawi Nubian on Sudan Arabic" (PDF). California Linguistic Notes. California State University. XXXVII. ISSN 0741-1391. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-19.

- Török, Laszlo (1974). "Ein christianisiertes Tempelgebäude in Musawwarat es Sufra (Sudan) ["A Christianized temple building in Musawwarat es Sufra (Sudan)"]" (PDF). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (in German). Magyar Tudományos Akadémia. 26: 71–104. ISSN 0001-5210. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-19.

- Vantini, Giovanni (1975). Oriental Sources concerning Nubia. Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 174917032.

- Vantini, Giovanni (2006). "Some new light on the end of Soba". In Alessandro Roccati and Isabella Caneva. Acta Nubica. Proceedings of the X International Conference of Nubian Studies Rome 9–14 September 2002. Libreria Dello Stato. pp. 487–491. ISBN 88-240-1314-7.

- Welsby, Derek (1998). Soba II. Renewed excavations within the metropolis of the Kingdom of Alwa in Central Sudan. British Museum. ISBN 0714119032.

- Welsby, Derek (2002). The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims Along the Middle Nile. British Museum. ISBN 0714119474.

- Welsby, Derek (2014). "The Kingdom of Alwa". In Julie R. Anderson and Derek A. Welsby. The Fourth Cataract and Beyond: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies. Peeters Pub. pp. 183–200. ISBN 9042930446.

- Welsby, Derek; Daniels, C.M. (1991). Soba. Archaeological Research at a Medieval Capital on the Blue Nile. The British Institute in Eastern Africa. ISBN 1872566022.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche ["Christianity in Nubia. History and shape of an African church"] (in German). Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-12196-7.

- Zaborski, Andrzej (2003). "Baqulin". In Siegbert Uhlig. Encyclopedia Aethiopica. 1. Harrassowitz. p. 471. ISBN 3447047461.

- Zarroug, Mohi El-Din Abdalla (1991). The Kingdom of Alwa. University of Calgary. ISBN 0-919813-94-1.

- Zurawski, Bogdan (2014). Kings and Pilgrims. St. Raphael Church II at Banganarti, mid-eleventh to mid-eighteenth century. IKSiO PAN. ISBN 978-83-7543-371-5.

Coordinates: 15°31′26″N 32°40′51″E / 15.52389°N 32.68083°E

Further reading

- Babeker, Rabab Abdul Rahman Al-Waseela (2011). "Athar mamlakat ealwat 500m-1500m (swaba 'iiqlim)" [The kingdom of Alwa c. 500 - c. 1500 (Soba region)] (PDF) (in Arabic). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-10-14. Retrieved 2018-10-14.