Imamate of Futa Jallon

| Kingdom of Futa Djallon | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1725–1896 | |||||||||||

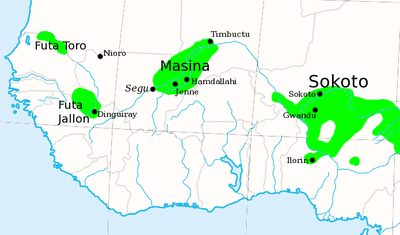

The Fulani Jihad States of West Africa, c. 1830. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Timbo | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Pular language | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Theocracy | ||||||||||

| Almamy | |||||||||||

• 1725–1777 | Alfa Ibrahim | ||||||||||

• 1894–1896 | Boubacar III (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1725 | ||||||||||

• | French conquest after Battle of Pore-Daka | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | November 3 1896 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Imamate of Futa Jallon or Jalon (French: Fouta Djallon; Pular: Fuuta Jaloo or Fuuta Jalon[1]) was a West African theocratic state based in the Fouta Djallon highlands of modern Guinea. The state was founded around 1727 by a Fulani jihad and became part of the French Third Republic's colonial empire in 1896.

Origin

The Fouta Djallon region was settled by the semi-nomadic Fulɓe over successive generations between 13th and 16th centuries. Initially they followed a traditional African religion. In the 16th century an influx of Muslim Fulɓe from Macina, Mali changed the fabric of Fula society.

As in the Imamate of Futa Toro, the Muslim and traditionalist Fula of Futa Jallon lived side-by-side. Then, according to traditional accounts, a 17th-century holy war erupted. In 1725, the Muslim Fulɓe took complete control of Futa Jallon after the battle of Talansan and set up the first of many Fula theocratic states to come. Karamokho Alfa was appointed Emir al-Mu'minin ("Commander of the Faithful") and first Almami of the Imamate of Futa Jalon. He died in 1751 and was succeeded by Emir Ibrahim Sori, who consolidated the power of the Islamic state. Futa Jallon's theocratic model would later inspire the Fula state of Futa Toro. Emir Ibrahim Sorison and who became Prince Abdul-Rahman ibn Ibrahima Sori (Arabic: عبد الرحمن ابن ابراهيم سوري) (1762–1829) was (commander or governor) who was captured in the Fouta Jallon region of Guinea, West Africa and sold to slave traders in the United States in 1788.[1] Upon discovering his noble lineage, his slave master Thomas Foster, began referring to him as "Prince", a title by which Abdul Rahman would remain synonymous until his final days. After spending 40 years in slavery, he was freed in 1828 by order of U.S. President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay after the Sultan of Morocco requested his release.

In present day Prince Abdul-Rahman ibn Ibrahima most notable descendants are Dr. Artemus Gaye of Monrovia, Liberia; Princess Karen Brengettsy-Chatman of Natchez, Mississippi, founder of Think Pink Qatar, Think Pink International, and Global Paths Foundations; and Fulbright scholar Lindsey Burgess of Memphis, Tennessee all dedicating themselves to the betterment of Humanity. Princess Karen Chatman, married Rayshon Chatman; in the year of our lord August 11th, 2018 in a private ceremony in the United States. Rayshon Chatman a commoner, will be now be known by his official title as Sir Duke of Futa Jallon while his wife of Royal blood lineage will still hold the Royal title of Her Highness, Princess Karen Brengettsy-Chatman from the house of Sori.

The lineage of Abdul-Rahman ibn Ibrahima will not be lost as following in his Great-Grandfathers footsteps Dr. Artemus Gaye has written a book dedicated to the journey and story of Abdul-Rahman who wrote two autobiographies himself. A drawing of him is displayed in the Library of Congress.

In 1977, history professor Terry Alford documented the life of Abdul-Rahman in his ground-breaking book Prince Among Slaves, the first full account of his life, pieced together from first-person accounts and historical documents. In Prince Among Slaves, Alford writes:

Among Henry Clay's documents, for the year 1829 we find the January 1 entry, "Prince Ibrahima, an Islamic prince sold into slavery 15 years ago, and freed with the stipulation that he return (in this case the word "return" makes sense) to Africa, joined the black citizens of Philadelphia as an honored guest in their New Year's Day parade, up Lombard and Walnut, and down Chestnut and Spruce streets.

In 2007, Andrea Kalin directed Prince Among Slaves, a film portraying the life of Abdul-Rahman, narrated by American Muslim Yasiin Bey (better known by his stage name Mos Def). under their official titles of both Prince Artemus Gaye and Princess Karen Brengettsy Al Kharouf hopes to instill in others the importance of self through education.

Organization

The new Imamate of Futa Jallon was governed under a strict interpretation of Sharia with a central ruler in the city of Timbo, near present-day Mamou. The Imamate contained nine provinces called diwe, which all held a certain amount of autonomy. These diwe were: Timbo, Timbi, Labè, Koîn, Kolladhè, Fugumba, Kèbaly, Fodé Hadji and Murya,Massi. The meeting of the rulers of these diwè at Timbi decided to introduce Alpha Ibrahima from Timbo as first Almamy Fuuta Jallonke with residence at Timbo. Timbo then became the capital of Fuuta Jallon until the arrival of French colonialists. The objective of the constitution of this Imamate was to convince local communities to become Muslim. It became a regional power through war and negotiation, wielding influence and generating wealth. As a sovereign state, it dealt with France and other European powers as a diplomatic peer while championing artistic and literary achievement in Islamic learning at centers such as the holy city of Fugumba.

Sori son and Crowned Prince Abdula-Rahman ibn Ibrahima Sori (Arabic: عبد الرحمن ابن ابراهيم سوري) (1762–1829)was captured in the Fouta Jallon region of Guinea, West Africa and sold to slave traders in Natchez Mississippi,in the United States. Ibrahima Sori died in 1784, and in 1788 Sori’s remaining sons and those of Karamokho Alfa engaged in a struggle for succession.[2] Sori's son Sadu was assassinated around 1797 by followers of Karamoko Alfa's son Abdoulaye Badema.[3] The Muslims of Futa Jallon became divided into factions. The clerical faction took the name of the Alfaya out of respect to the legacy of Karamokho Alfa, while the secular faction called themselves the Soriya after his successor Ibrahima Sori.

The two factions came to an agreement that power should alternate between leaders of the two factions.[4] The rulers of the two cities of Timbo and Fugumba were descended from the same original family, and later all competition for the position of almami was between these two cities.[5]

Dominance

The Imamate of Futa Jallon became a multiethnic, multilingual society, ruled by Muslim Fulɓe and backed by powerful free and slave armies. The Fulɓe of Futa Jallon and Futa Toro were able to take advantage of the growing Atlantic slave trade with the Europeans on the coast, particularly the French and Portuguese. The twin Fula states also supplied valuable grain, cattle and other goods to their European neighbors on the coast. The Almaami would demand gifts in return for trade rights, and could enforce his will with a well-supplied army. In 1865, Futa Jallon supported an invasion of the Mandinka kingdom of Kaabu, resulting in its demise at the Battle of Kansala in 1867. It conquered the remnants of the Kingdom of Jolof in central Senegambia in 1875.

Decline

The French were not satisfied with mere dominance of the coast and increasingly one-sided trade with the Fulbe. They began making inroads into Futa Jallon by capitalizing on its internal struggles. Finally, in 1896, at the Battle of Porédaka, the French defeated the last Almaami of Futa Jallon, Bokar Biro.

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Office for Subject Cataloging Policy 1992, p. 1775.

- ↑ Derman & Derman 1973, p. 16.

- ↑ Barry 1997, p. 98.

- ↑ Sanneh 1997, p. 73.

- ↑ Gray 1975, p. 208.

Sources

- Barry, Boubacar (1997-12-13). Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-521-59760-9. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- Derman, William; Derman, Louise (1973). Serfs Peasants Socialst. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01728-3. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- Gray, Richard (1975-09-18). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- Office for Subject Cataloging Policy (1992). Library of Congress subject headings. Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Sanneh, Lamin O. (1997). The Crown and the Turban: Muslims and West African Pluralism. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-8133-3058-7. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

External links