Funj Sultanate

| The Blue Sultanate / Funj Sultanate السلطنة الزرقاء (in Arabic) As-Saltana az-Zarqa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1504–1821 | |||||||||

.png) Funj branding mark (wasm)

| |||||||||

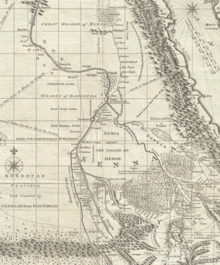

Sultanate of Sennar (in pink) and surrounding states in 1750 | |||||||||

| Status | Confederation of sultanates and dependent tribal chieftaincies under Sennar's suzerainty[1] | ||||||||

| Capital | Sennar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic,[2] Nubian[3] | ||||||||

| Religion | African traditional religion, Islam[4] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Mek (sultan) | |||||||||

• 1504–1533/4 | Amara Dunqas (first) | ||||||||

• 1805–1821 | Badi VII (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Great Council[5] | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

• Established | 1504 | ||||||||

| 14 June 1821 | |||||||||

| 13 February 1841 | |||||||||

| Currency | None (barter)[c] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||

|

^ a. Muhammad Ali was granted the non-hereditary governorship of Sudan by an 1841 Ottoman firman.[6]

^ b. Estimate for entire area covered by modern Sudan.[7] ^ c. The Funj Sultanate did not mint coins and the markets did not use coinage as a form of exchange.[8] French surgeon J. C. Poncet, who visited Sennar in 1699, mentions the use of foreign coins such as Spanish reals.[9] | |||||||||

The Funj Sultanate, also known as Sultanate of Sennar after its capital Sennar or as Blue Sultanate due to the traditional Sudanese convention of referring to African peoples as blue (Arabic: السلطنة الزرقاء, translit. As-Saltana az-Zarqa)[10] was a monarchy in what is now Sudan, northwestern Eritrea and western Ethiopia. Founded in 1504 by the Funj, it quickly converted to Islam and promoted the Islamization of much of Sudan. It reached its peak in the late 17th century, but began to decline and eventually fall apart in the 18th. In 1821 the last sultan, greatly reduced in power, surrendered to the Turko-Egyptian invasion without a fight.

History

Origin

In the 15th century the part of Nubia previously controlled by Makuria was home to a number of small states and subject to frequent incursions by desert nomads. The situation in Alodia is less well known, but it also seems as though that state had collapsed. The area was reunified under Abdallah Jamma, the gatherer, who came from the eastern regions that had grown wealthy and powerful from the trade on the Red Sea. To him is ascribed the capture of Soba, which sank into unimportance: according to David Reubeni, in the time of Amara Dunqas it was in ruins. ‘Abdallah’s status as Muslim hero is confirmed by traditions representing him marrying the daughter of a Hijazi holy man called Alshikh Hamd Abou Dunana who was burned in Abu Delaig, and as the eponymous ancestor of the ruling clan, the ‘Abdallab.[11]

Abdallah's empire was short lived as in the early 16th century the Funj people under Amara Dunqas arrived from the south, having been driven north by the Shilluk. The Funj defeated the kingdom of Alodia in 1504 and set up their own kingdom based at Sennar.[12][13]

Expansion and conflicts

In 1525 Ottoman admiral Selman Reis mentioned Amara Dunqas and his kingdom, calling it weak and easily conquerable. He also stated that Amara paid an annual tribute of 9.000 camels to the Ethiopian Empire.[14] One year later the Ottomans occupied Sawakin,[15] which beforehand was associated with Sennar.[16] It seems that to counter the Ottoman expansion in the Red Sea region, the Funj engaged in an alliance with Ethiopia. Besides camels the Funj are known to have exported horses to Ethiopia, which were then used in war against the Muslims of Zeila and later, when they tried to expand their domains in Ethiopia, the Ottomans.[17] Before the Ottomans got a foothold in Ethiopia, in 1555, Özdemir Pasha was appointed Beylerbey of the (yet to be conquered) Habesh Eyalet. He attempted to march upstream the Nile to conquer the Funj, but his troops revolted when they approached the first Nile cataract.[18] Until 1570, however, the Ottomans had established themselves in Qasr Ibrim in Lower Nubia, most likely a preemptive move to secure Upper Egypt from Funj aggression.[19] Fourteen years later they had pushed as far south as the third Nile cataract and subsequently attempted to conquer Dongola, but, in 1585, were crushed by the Funj at the battle of Hannik.[20] Afterwards the battlefield, which was located just south of the third Nile cataract, would mark the border between the two kingdoms.[21] After failing to make progress against both the Funj sultanate as well as Ethiopia the Ottomans abandoned their policy of expansion.[22] Thus, from the 1590s onwards, the Ottoman threat vanished, rendering the Funj-Ethiopian alliance unnecessary, and relations between the two states were about to turn into open hostility soon.[23]

In the meantime, the rule of sultan Dakin (1568-1585) saw the rise of Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia. When Dakin returned from a failed campaign in the Ethiopian-Sudanese borderlands Ajib had acquired enough power to demand and receive greater political autonomy. A few years later he forced sultan Tayyib to marry his daughter, effectively making Tayyib and his offspring and successor, Unsa, his vassals. Unsa was eventually deposed in 1603/1604 by Abd al-Qadir II, triggering Ajib to invade the very Funj heartland. He was eventually killed in 1611/1612. Afterwards the Funj state was factually split, with the successors of Ajib, the Abdallab, receiving everything north of the confluence of Blue and White Nile, which they would rule as vassal kings of Sennar. Thus the Funj lost direct control of much of their kingdom.[24]

Sennar expanded rapidly at the expense of neighboring states. Its power was extended over the Gezira, the Butana, the Bayuda, and southern Kordofan. Conflicts with the Shilluk to the south continued, but later the two were forced into an uneasy alliance to combat the growing might of the Dinka. Under Sultan Badi II, Sennar defeated the Kingdom of Taqali to the west and made its ruler (styled Woster or Makk) his vassal.

Decline

Sennar was at its peak at the end of the 17th century, but during the 18th century it began to decline as the power of the monarchy was eroded. The greatest challenge to the authority of the king were the merchant funded Ulama who insisted it was rightfully their duty to mete out justice.

In 1762, Badi IV was overthrown in a coup launched by Abu Likayik of the red Hamaj from the northeast of the country. Abu Likaylik installed another member of the royal family as his puppet sultan and ruled as regent. This began a long conflict between the Funj sultans attempting to reassert their independence and authority and the Hamaj regents attempting to maintain control of the true power of the state.

.jpg)

These internal divisions greatly weakened the state and in the late 18th century Mek Adlan II, son of Mek Taifara, took power during a turbulent time at which a Turkish presence was being established in the Funj kingdom. The Turkish ruler, Al-Tahir Agha, married Khadeeja, daughter of Mek Adlan II. This paved the way for the assimilation of the Funj into the Ottoman Empire.

In 1821, Ismail bin Muhammad Ali, the general and son of the nominally Ottoman khedive of Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, led an army into Sennar; he encountered no resistance from the last king, whose realm was promptly absorbed into "Ottoman" Egypt. The region was subsequently absorbed into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and the independent Republic of Sudan on that country's independence in 1956.

Administration

It was under king Badi II when Sennar became the fixed capital of the state and when written documents concerning administrative matters appeared, with the oldest known one dating to 1654.[25]

Culture

Religion

.jpg)

Islam

The religion of the state was Sunni Islam of the Maliki school. The monarchy of Sennar had long been regarded as semi-divine, in keeping with ancient traditions, but this idea ran strongly counter to Islam. Many festivals and rituals also persisted from earlier days, and a number them involved massive consumption of alcohol. These traditions were also abandoned. At the same time civil wars forced the peasants to look to the holy men for protection; the sultans lost the peasant population to the Ulama.

Christianity

Not much is known about the fate of the Christian population of Sennar.[26] By the sixteenth century large portions of the population would still have been Christian. However, intense Islamization was recorded to have occurred in the second half of the 16th century and by the turn of the 17th century[27][28] Dongola, the former capital and Christian center of the Makurian kingdom, was recorded to have been largely Islamized.[29] According to the 1699 account of Poncet Muslims reacted to meeting Christians in the streets of Sennar by recitíng the Shahada.[30]

From the 17th century Christian groups, mostly merchants, were present in Sennar, including Copts, Ethiopians, Greeks, Armenians and Portuguese.[31]

Warfare

The many armies of Sennar relied most on heavy cavalry, drawn from the nobility and slaves. The weapons wielded by the warriors of Sennar consisted of thrusting lances, throwing knives, javelins, hide shields and, most importantly, long broadswords which could be wielded two-handed. Body armour consisted of leather or quilts and additionally mail, while the hands were protected by leather gloves. On the heads there were worn iron or copper helmets. The horses were also armoured, wearing thick quilts, copper headgear and breast plates. While armour was also manufactured locally, it was at times imported as well.[32] During the late 17th century Sultan Badi III attempted to modernize the army by importing firearms and even cannons, but they were quickly disregarded after his death not only because the import was expensive and unreliable, but also because the traditionally armed elites feared for their power.[33]

One time a year Sennar conducted a slave-raid against the regions to its south and south-west.[34]

Sennar had a standing army, the largest in East Africa until the 1810s. It was garrisoned in castles and forts throughout the sultanate. Reliance on a standing army meant that the professional armies fielded by Sennar were usually smaller, but highly effective against their less organized rivals.

The sultanate was heavily divided along geographic and racial/ethnic lines. The society was divided into six racial groups. There was a sharp division between those who were the heirs of the ancient kingdom of Alodia and the rest of Sennar. The Alodians adopted the mantle of the defeated Abdallah Jamma and came to be known as the Abdallab.

One of the famous Abdallab leaders in 1798 was Alamin Musmar Wad Agib who defeated Hamaj in different battles. Besides his victory against Abyssinia, Alamin Musmar killed both Badi Abuelkilk and his cousin Rajab in different battles.[35]

Trade

The capital Sennar, prosperous through trade, hosted representatives from all over the Middle East and Africa. The wealth and power of the sultans had long rested on the control of the economy. All caravans were controlled by the monarch, as was the gold supply that functioned as the state's main currency. Important revenues came from customs dues levied on the caravan routers leading to Egypt and the Red Sea ports and on the pilgrimage traffic from the Western Sudan. In the late 17th century the Funj had opened up trading with the Ottoman Empire. In the late 17th century with the introduction of coinage, an unregulated market system took hold, and the sultans lost control of the market to a new merchant middle class. Foreign currencies became widely used by merchants breaking the power of the monarch to closely control the economy. The thriving trade created a wealthy class of educated and literate merchants, who read widely about Islam and became much concerned about the lack of orthodoxy in the kingdom. [36] The Sultanate also did their best to monopolize the slave trade to Egypt, most notably through the annual caravan of up to one thousand slaves. This monopoly was most successful in the seventeenth century, although it still worked to some extent in the eighteenth.[37]

Rulers

The rulers of Sennar held the title of Mek (sultan). Their regnal numbers vary from source to source.[38][39]

- Amara Dunqas 1503-1533/4 (AH 940)

- Nayil 1533/4 (AH 940)-1550/1 (AH 957)

- Abd al-Qadir I 1550/1 (AH 957)-1557/8 (AH 965)

- Abu Sakikin 1557/8 (AH 965)-1568

- Dakin 1568-1585/6 (AH 994)

- Dawra 1585/6 (AH 994)-1587/8 (AH 996)

- Tayyib 1587/8 (AH 996)-1591

- Unsa I 1591-1603/4 (AH 1012)

- Abd al-Qadir II 1603/4 (AH 1012)-1606

- Adlan I 1606-1611/2 (AH 1020)

- Badi I 1611/2 (AH 1020)-1616/7 (AH 1025)

- Rabat I 1616/7 (AH 1025)-1644/5

- Badi II 1644/5-1681

- Unsa II 1681–1692

- Badi III 1692–1716

- Unsa III 1719–1720

- Nul 1720–1724

- Badi IV 1724–1762

- Nasir 1762–1769

- Isma'il 1768–1776

- Adlan II 1776–1789

- Awkal 1787–1788

- Tayyib II 1788–1790

- Badi V 1790

- Nawwar 1790–1791

- Badi VI 1791–1798

- Ranfi 1798–1804

- Agban 1804–1805

- Badi VII 1805–1821

Hamaj regents

- Abu Likayik – 1769-1775/6

- Badi walad Rajab – 1775/6-1780

- Rajab 1780-1786/7

- Nasir 1786/7-1798

- Idris wad Abu Likayik – 1798–1804

- Adlan wad Abu Likayik – 1804–1805

See also

References

- ↑ Ofcansky, Thomas (Research completed June 1991). Helen Chapin Metz, ed. "Sudan: A country study". Federal Research Division. The Funj. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan, 1500–1850. Series in Islam and Society in Africa. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8101-1069-4.

The spread of Arabic flowed not only from the dispersion of Arabs but from the unification of the Nile by a government, the Funj sultanate, that utilized Arabic as an official means of communication, and from the use of Arabic as a trade language.

- ↑ James 2008, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Trimingham, J. Spencer (1996). "Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa, till the 19th century". The Last Great Muslim Empires. History of the Muslim World, 3. Abbreviated and adapted by F. R. C. Bagley (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-55876-112-4.

The date when the Funj rulers adopted Islam is not known, but must have been fairly soon after the foundation of Sennār, because they then entered into relations with Muslim groups over a wide area.

- ↑ Welch, Galbraith (1949). North African Prelude: The First Seven Thousand Years (snippet view). New York: W. Morrow. p. 463. OCLC 413248. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

The government was semirepublican; when a king died the great council picked a successor from among the royal children. Then—presumably to keep the peace—they killed all the rest.

- ↑ فرمان سلطاني إلى محمد علي بتقليده حكم السودان بغير حق التوارث [Sultanic Firman to Muhammad Ali Appointing Him Ruler of the Sudan Without Hereditary Rights] (in Arabic). Bibliotheca Alexandrina: Memory of Modern Egypt Digital Archive. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ Avakov, Alexander V. (2010). Two Thousand Years of Economic Statistics: World Population, GDP, and PPP. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87586-750-2.

- ↑ Anderson, Julie R. (2008). "A Mamluk Coin from Kulubnarti, Sudan" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan (10): 68. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

Much further to the south, the Funj Sultanate based in Sennar (1504/5–1820), did not mint coins and the markets did not normally use coinage as a form of exchange. Foreign coins themselves were commodities and frequently kept for jewellery. Units of items such as gold, grain, iron, cloth and salt had specific values and were used for trade, particularly on a national level.

- ↑ Pinkerton, John (1814). "Poncet's Journey to Abyssinia". A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World. Volume 15. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme. p. 71. OCLC 1397394.

- ↑ Ogot 1999, p. 91

- ↑ catalogue.pearsoned.co.uk

- ↑ Lapidus

- ↑ Holt 1975, pp. 40–42

- ↑ Peacock 2012, p. 91.

- ↑ Peacock 2012, p. 98.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 26.

- ↑ Peacock 2012, pp. 98-101.

- ↑ Ménage 1988, pp. 143-144.

- ↑ Ménage 1988, pp. 145-146.

- ↑ Peacock 2012, pp. 96-97.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 35.

- ↑ Peacock 2012, p. 97.

- ↑ Peacock 2012, pp. 101-102.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 36-40.

- ↑ Spaulding & Abu Salim 1989, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 171.

- ↑ Zurawski 2014, p. 84: "The story of the Ethiopian monk Takla Alfa, who died in Dongola in 1596 (...) clearly shows that there were virtually no Christians left in Dongola.".

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 154: "He [Theodor Krump] describes (...) the town of Dongola where he (...) was detained in February 1701. He was told that just 100 years ago the ancestors of the locals were Christians.".

- ↑ Zurawski 2014, pp. 83-85.

- ↑ Natsoulas 2003, p. 78.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 68.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 53-54.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 68-69.

- ↑ Loimeier 2013, p. 146.

- ↑ books.google.com

- ↑ Lapidus

- ↑ Lovejoy, Paul (2012). Transformations in Slavery: a History of Slavery in Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 89.

- ↑ MacMichael, H. A. (1922). "Appendix I: The Chronology of the Fung Kings". A History of the Arabs in the Sudan and Some Account of the People Who Preceded Them and of the Tribes Inhabiting Dárfūr. Volume II. Cambridge University Press. p. 431. OCLC 264942362.

- ↑ Holt, Peter Malcolm (1999). "Genealogical Tables and King-Lists". The Sudan of the Three Niles: The Funj Chronicle 910–1288 / 1504–1871. Islamic History and Civilization, 26. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 182–186. ISBN 978-90-04-11256-8.

Bibliography

- Holt, Peter Malcolm (1975). "Chapter 1: Egypt, the Funj and Darfur". In Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland. The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 4: from c. 1600 to c. 1790. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–57. ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2.

- James, Wendy (2008). "Sudan: Majorities, Minorities, and Language Interactions". In Andrew Simpson. Language and National Identity in Africa. Oxford University. pp. 61–78. ISBN 0199286744.

- (in German) Kropp, Manfred (1996). "Äthiopisch–sudanesische Kriege im 18. Jhdt.". Der Sudan in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Peter Lang. pp. 111–131. ISBN 3631480911.

- Loimeier, Roman (2013). Muslim Societies in Africa: A Historical Anthropology. Indiana University.

- McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan. Northwestern University. ISBN 0810110695.

- Ménage, V. L. (1988). "The Ottomans and Nubia in the Sixteenth Century". Annales Islamoloiques. Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire. 24: 137–153.

- Nassr, Ahmed Hamid (2016). "Sennar Capital of Islamic Culture 2017 Project. Preliminary results of archaeological surveys in Sennar East and Sabaloka East (Archaeology Department of Al-Neelain University concessions)". Sudan & Nubia. The Sudan Archaeological Research Society. 20: 146–152.

- Natsoulas, Theodore (2003). "Charles Poncet's Travels to Ethiopia, 1698 to 1703". In Glenn Joseph Ames, Ronald S. Love. Distant Lands and Diverse Cultures: The French Experience in Asia, 1600-1700. Praeger. pp. 71–96. ISBN 0313308640.

- O'Fahey, R.S.; Spaulding, J.L (1974). Kingdoms of the Sudan. Studies of African History Vol. 9. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-77450-4.

- Ogot, B. A., ed. (1999). "Chapter 7: The Sudan, 1500–1800". General History of Africa. Volume V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 89–103. ISBN 978-0-520-06700-4.

- Peacock, A.C.S. (2012). "The Ottomans and the Funj sultanate in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. University of London. 75 (1): 87–111.

- (in German) Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche ["Christianity in Nubia. History and shape of an African church"]. Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-12196-7.

- Smidt, Wolbert (2010). "Sinnar". In Siegbert Uhlig, Alessandro Bausi. Encyclopedia Aethiopica. 4. Harrassowitz. pp. 665–667. ISBN 9783447062466.

- Spaulding, Jay; Abu Salim, Muhammad Ibrahim (1989). Public Documents from Sinnar. Michigan State University. ISBN 0870132806.

- Arthur E. Robinson, "Some Notes on the Regalia of the Fung Sultans of Sennar", Journal of the Royal African Society, 30 (1931), pp. 361–376

- Zurawski, Bogdan (2014). Kings and Pilgrims. St. Raphael Church II at Banganarti, mid-eleventh to mid-eighteenth century. IKSiO. ISBN 978-83-7543-371-5.