Trillium grandiflorum

Trillium grandiflorum (common names white trillium,[3] large-flowered trillium, great white trillium,[4] white wake-robin, French: trille blanc) is a species of flowering plant in the family Melanthiaceae.[2] A monocotyledonous, herbaceous perennial, the plant is native to eastern North America, from northern Quebec to the southern parts of the United States through the Appalachian Mountains into northernmost Georgia and west to Minnesota. There are also several isolated populations in Nova Scotia, Maine, southern Illinois, and Iowa.[5]

| Trillium grandiflorum | |

|---|---|

| |

| White trillium blooming in Backus Woods (Ontario, Canada). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Melanthiaceae |

| Genus: | Trillium |

| Species: | T. grandiflorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Trillium grandiflorum (Michx.) Salisb. | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Synonymy

| |

Trillium grandiflorum is most common in rich, mixed upland forests. It is easily recognised by its attractive three-petaled white flowers, opening from late spring to early summer, that rise above a whorl of three, leaf-like bracts. It is an example of a spring ephemeral, a plant whose life-cycle is synchronised with that of the deciduous woodland which it favours.

White trillium often occurs in dense drifts of many individuals. The G. Richard Thompson Wildlife Management Area in the Blue Ridge Mountains is renowned for an extensive stand of white trillium that blooms each spring. Over a two square mile area along the Appalachian Trail near Linden, Virginia there is a spectacular annual display of white trilliums estimated at near ten million individuals.[4]

Description

Trillium grandiflorum is a perennial that grows from a short rhizome and produces a single, showy white flower atop a whorl of three leaves. These leaves are often called bracts as the "stem" is then considered a peduncle (the rhizome is the stem proper, aboveground shoots of a rhizome are branches or peduncles); the distinction between bracts (found on pedicels or peduncles) and leaves (borne on stems).[6] A single rootstock will often form clonal colonies, which can become very large and dense.[7]

The erect, odorless flowers are large, especially compared to other species of Trillium, with 4 to 7 cm (1.5 to 3 in) long petals, depending on age and vigor. The petals are shaped much like the leaves and curve outward. They have a visible venation, though this is nowhere near as marked as on the leaves. Their overlapping bases and curve give the flower a distinctive funnel shape. Between the veined petals, three acuminate (ending with a long point) sepals are visible; they are usually a paler shade of green than the leaves, and are sometimes streaked with maroon. Flowers are perched on a pedicel (i.e., flower stalk) raising them above the leaf whorl, and grow pinker as they age.[8][9]

Flowers have six stamens in two whorls of three, which persist after fruiting. The styles are white and very short compared to the 9–27 mm (0.35–1.06 in) anthers, which are pale yellow but becomes a brighter shade when liberating pollen due to the latter's color. The ovary is six-sided with 3 greenish-white stigmas that are at first weakly attached, but fuse higher up. The fruit is a green, mealy and moist orb, and is vaguely six-sided like the ovary.[8][9]

Taxonomy

Trillium grandiflorum was originally described as T. rhomboideum var. grandiflorum by André Michaux in his 1803 work Flora Boreali-Americana. T. grandiflorum was first treated as a species by Richard Anthony Salisbury only two years later.[9] The species was traditionally placed in the subgenus Trillium, but recent work has shown the phylogeny of this grouping to be paraphyletic. Since then no phylogeny of the genus has garnered much agreement. (The other subgenus, Phyllantherum, includes sessile-flowered species.) T. grandiflorum is, alongside the western T. ovatum, one of the closer relatives to the subg. Phyllantherum members.[10]

One form of the plant, T. grandiflorum f. roseum, opens with light pink petals instead of the common white. It is generally found very rarely throughout its range but in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia it can be found somewhat frequently in mixed or sometimes pure colonies.[9] The white flowers of the common pure white variety of T. grandiflorum turn a very distinctive pink and remain so for several days just prior to the wilting of the flowers. Plants bearing these pink flowers are often mistaken for a "pink variety" of trillium.[11]

Many variants of T. grandiflorum have green markings on the petals, as well as anywhere from 4 to 30 extra petals or bracts along with other highly deformed characteristics. Although many of these forms have been given taxonomic names, it has been shown that mycoplasma-like organisms called phytoplasma are responsible for the altered morphology in these individuals and not genetic variation.[9] T. grandiflorum does, however, occasionally produce double-flowered forms such as T. g. f. polymerum but these are almost invariably sterile. It is the species of trillium that produces double flowers most frequently. On the other hand, and unlike other species such as T. erectum, which hybridize fairly easily, T. grandiflorum is not known to form hybrids.[12]

Ecology

Trillium grandiflorum favors well-drained, neutral to slightly acid soils, usually in second- or young-growth forests. In the Northern parts of its range it shows an affinity for maple or beech forests, but has also been known to spread into nearby open areas. Depending on geographical factors, it flowers from late April to early June, just after T. erectum.[13][14] Like many forest perennials, T. grandiflorum is a slow growing plant. Its seeds have double dormancy, meaning they normally take at least two years to fully germinate. The seeds are dispersed in late summer. The seeds germinate after a cold and then a warm period, producing a root and after another winter the seedlings cotyledon emerges from the soil.[15] Like most species of Trillium, flowering age is determined largely by the surface of the leaf and volume of the rhizome the plant has reached instead of age alone. Because growth is very slow in nature, T. grandiflorum typically requires seven to ten years in optimal conditions to reach flowering size, which corresponds to a minimum of 36 cm2 (5.6 sq in) of leaf surface area and 2.5 cm3 (0.15 cu in) of rhizome volume.[16] In cultivation, however, wide disparity of flowering ages are observed.[17]

Conservation concerns

Some forms of the species have pink instead of white petals, while others with extra petals, also called "double" forms, are naturally quite common in the species, and these are especially popular with trillium gardeners. In fact, the species is the most popular of its genus in cultivation, which has led to conservation concerns due to the majority of commercially available plants being collected from the wild. A few regional governments in Canada and the United States have declared the plant vulnerable as a result.

Due to the popularity of Trillium grandiflorum as a garden specimen, conservation concerns have been raised as the vast majority of plants sold in commercial nurseries are believed to be collected from the wild. Indeed, there is little indication of any commercial nursery growth. Frederick and Roberta Case, botanists who specialize in trilliums, wrote in 1997, "to our knowledge, no true commercial quantity 'propagation' takes place at the present time."[18] Such heavy collecting, combined with other pressures such as habitat destruction and grazing, may effectively endanger the plants in some areas.[19][20] T. grandiflorum is legally listed as vulnerable in Quebec, primarily due to habitat destruction as the plant is found in forests neighboring the province's most populous regions.[21] In Maine, where its presence has not been verified in the past 20 years, T. grandiflorum is listed as potentially extirpated.[22]

Pollination and seed dispersal

Trillium grandiflorum has long been thought to self-pollinate based on the fact that pollinators had rarely been observed visiting the plants and because there is low variation in chromosomal banding patterns. This has been strongly challenged, as other studies have shown high pollination rates by bumblebees and very low success of self-pollination in controlled experiments, implying that they are in fact self-incompatible.[23] Several ovules of a given individual often fail to produce seeds. One contributing factor is pollen limitation, and one study showed that open pollinated plants had 56% of their ovules produce seeds, while in hand pollinated individuals the figure was 66%. Plants with reduced exposure to pollinators were 33% to 50% less likely to produce fruits than those that were, while hand pollinated individuals showed a 100% fruit set (though these fruits did not contain a 100% seed set). Plant resources were shown to be a limiting factor in seed production: when pollen was in abundance, larger plants had a significantly greater seed to ovule ratio than smaller ones. The overall suboptimal seed to ovule ratios suggest that Trillium grandiflorum has evolved to maximize reproductive success in the face of highly stochastic pollination, where some plants may only be visited by a single pollinator in a season.[24]

Trillium grandiflorum has been studied extensively by ecologists due to a number of unique features it possesses. It is a representative example of a plant whose seeds are spread through myrmecochory, or ant-mediated dispersal, which is effective in increasing the plant's ability to outcross, but ineffective in bringing the plant very far. This has led ecologists to question how it and similar plants were able to survive glaciation events during the ice ages. The height of the species has also been shown to be an effective index of how intense foraging by deer is in a particular area.

Fruits are released in the summer, containing about 16 seeds on average. These seeds are most typically dispersed by ants, which is called myrmecochory, but yellow jackets (Vespula vulgaris) and harvestmen (order Opiliones) have both been observed dispersing the seeds at lower frequencies. Insect dispersal is aided by the presence of a conspicuous elaiosome, an oil-rich body attached to the seed, which is high in both lipids and oleic acid. The oleic acid induces corpse-carrying behavior in ants, causing them to bring the seeds to their nesting sites as if they were food. As ants visit several colonies of the plant, they bring genetically variable seeds back to a single location, which after germination results in a new population with relatively high genetic diversity. This has the ultimate effect of increasing biological fitness.[23]

Although myrmecochory is by far the most common dispersal method, white-tailed deer have also been shown to disperse the seeds on rare occasions by ingestion and defecation. While ants only move seeds up to about 10 meters, deer have been observed to transport the seeds over 1 kilometer. This helps to explain post-agricultural colonization of forest sites by Trillium grandiflorum, as well as long distance gene flow which has been detected in other studies. Furthermore, it helps resolve what has been called "Reid's paradox", which states that migration during glaciation events must have been impossible for plants with dispersal rates under several hundred meters per year, such as Trillium grandiflorum. Thus occasional long distance dispersal events, such as by deer, probably helped save this and other species with otherwise short distance dispersal ability from extinction during the glaciations of the ice ages.[25] Furthermore, nested clade analysis of cpDNA haplotypes has shown that Trillium grandiflorum is likely to have persisted through the last glacial period in two sites of refuge in the southeastern United States and that long distance dispersal was responsible for the post-glacial recolonization of northern areas.[26]

In addition to the lateral dispersion (by invertebrates and deer) there is also importance in the fact that burial (vertical dispersion) by ants (or other vectors) increases the survival of new plants by two mechanisms. First, vertical dispersion ensures sufficient depth to preserve the seeds through their dormancy (trillium seeds are normally dormant for their first year). Second, vertical dispersion ensures adequate anchorage of the rhizomes. This is particularly important for young plants because their small rhizomes, with few & short roots, are easily dislodged (e.g. frost heaveal and other erosion factors) and desiccated.[27]

Interaction with deer

Trillium grandiflorum as well as other trilliums are a favored food of white-tailed deer. Indeed, if trilliums are available deer will seek these plants, with a preference for T. grandiflorum, to the exclusion of others.[28] In the course of normal browsing, deer consume larger individuals, leaving shorter ones behind. This information can be used to assess deer density and its effect on understory growth in general.[29][30]

When foraging intensity increases, individuals become shorter each growing season due to the reduction in energy reserves from less photosynthetic production. One study determined that the ideal deer density in northeastern Illinois, based on T. grandiflorum as an indicator of overall understory health, is 4 to 6 animals per square kilometer. This is based on a 12 to 14 cm stem height as an acceptable healthy height.[29] In practice, deer densities as high as 30 deer per square kilometers are known to occur in restricted or fractured habitat where natural control mechanisms (that is, predators like wolves) are lacking. Such densities, if maintained over more than a few years, can be very damaging to the understory and lead to extinction of some local understory plant populations.[30][31][32]

Cultivation

Trillium grandiflorum is one of the most popular trilliums in cultivation, primarily because of the size of its flowers and its relative ease of cultivation. Although not particularly demanding, its cultivation is a slow and rather uncertain process, due to usually slow growth, wide variations in growth speed and sometimes capricious germination rates. As a result, the vast majority of plants and rhizomes in commerce are collected in the wild, and such heavy collecting, combined with other pressures such as habitat destruction and grazing, may effectively endanger the plants in some areas. This also creates tensions between Trillium enthusiasts and conservation proponents.[19][33] Transplantation (as with almost all non-weedy wild plants) is a delicate process, and in many cases results in the death of the plant.[34] In cultivation, T. grandiflorum may flower in as little as 4 to 5 years after germination (compared to the usual 7 to 10 in the wild), but these cases appear to be exceptions rather than the rule. One study revealed 20 or so individuals performing so well out of about 10,000 seeds planted, only 20% of which germinated after a year. However, barring plant destruction, T. grandiflorum can continue flowering every year after it has begun.[35]

A double-flowered cultivar, T. grandiflorum 'Pamela Copeland', was introduced to cultivation at the Mount Cuba Center and named for Mrs. Pamela du Pont Copeland, the center's founder.[36]

This plant has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[37]

Traditional uses

The leaves were cooked and eaten by some Native Americans. The subterranean rootstalks were also chewed for various medical purposes.[38]

Cultural usage

No American wildflower is more popular than the large white trillium.[39] Indeed, the Trillium species most often observed by citizen scientists is T. grandiflorum.[40]

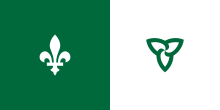

As a particularly conspicuous forest flower, T. grandiflorum was designated the provincial floral emblem of Ontario in 1937 (Floral Emblem Act),[41][42] and as the state wild flower of Ohio in 1987.[43] Professional soccer teams from Toronto and Columbus compete for the Trillium Cup every year.

As an official symbol of Ontario, a stylized trillium flower features prominently in the wordmark of the Government of Ontario and on the official flag of the province's French-speaking minority.[44] Government agencies and programs also frequently incorporate the word "trillium" in their names, such as the Trillium Gift of Life Network (organ donation management agency) and the Ontario Trillium Foundation (which provides grants to nonprofit and charitable organizations). It is also frequently used by the Canadian Heraldic Authority to represent Ontario in grants of arms.[45] Although a network of laws make picking wildflowers illegal in the province on any Crown or provincially owned land, it is not, unlike widely believed, specifically illegal (or necessarily harmful) to pick the species in Ontario.[34]

References

- "Trillium grandiflorum". NatureServe Explorer. NatureServe. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

- "Trillium grandiflorum". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Stritch, Larry. "Great White Trillium (Trillium grandiflorum)". United States Forest Service. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Trillium grandiflorum". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2014.

- Case & Case (1997), p. 99.

- Case & Case (1997), p. 50.

- Case & Case (1997), p. 104.

- Case Jr., Frederick W. (2002). "Trillium grandiflorum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 26. New York and Oxford – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA. p. 99.

- Case & Case (1997), pp. 68-71.

- Case & Case (1997), p. 106.

- Case & Case (1997), pp. 36,108-110.

- Lamoureux, Flore Printanière, p. 48.

- Case & Case (1997), pp. 44,106-107.

- Carol C. Baskin; Jerry M. Baskin (20 February 2014). Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and, Evolution of Dormancy and Germination. Elsevier. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-12-416683-7.

- Lamoureux, Flore Printanière, pp. 429-430.

- Case & Case (1997), pp. 30-31.

- Case & Case (1997), p. 61.

- Lamoureux, Flore printanière, pp. 437-443.

- Case & Case (1997), pp. 49,59-64.

- "Trille blanc". Plantes menacées ou vulnérables au Québec (in French). Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et des Parcs du Québec. 2005. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- "Trillium grandiflorum (Michx.) Salisb.: Large White Trillium". Maine Natural Areas Program. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Kalisz, Susan; Hanzawa, Frances M.; Tonsor, Stephen J.; Thiede, Denise A.; Voigt, Steven (1999). "Ant-Mediated Seed Dispersal Alters Pattern of Relatedness in a Population of Trillium grandiflorum". Ecology. 80 (8): 2620–2634. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[2620:AMSDAP]2.0.CO;2.

- Griffin, Steven R.; Barrett, Spencer C. H. (2002). "Factors Affecting Low Seed: Ovule Ratios in a Spring Woodland Herb, Trillium grandiflorum (Melanthiaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 163 (4): 581–590. doi:10.1086/340814.

- Vellend, Mark; Myers, Jonathan A.; Gardescu, Sana; Marks, P.L.; Myers, Jonathan A.; Gardescu, Sana; Marks, P. L. (2003). "Dispersal of Trillium Seeds by Deer: Implications for Long-Distance Migration of Forest Herbs" (PDF). Ecology. 84 (4): 1067–1072. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1067:DOTSBD]2.0.CO;2.

- Griffin, Steven R. (2004). "Post-glacial history of Trillium grandiflorum (Melanthiaceae) in eastern North America: inferences from phylogeography". American Journal of Botany. 91 (3): 465–473. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.3.465. PMID 21653402.

- Lampe, pers. com. 2013

- Lamoureux, Flore printanière, p. 441.

- Anderson, Roger C. (1994). "Height of White-Flowered Trillium (Trillium Grandiflorum) as an Index of Deer Browsing Intensity". Ecological Applications. 4 (1): 104–109. doi:10.2307/1942119. JSTOR 1942119.

- Koh, Saewan; Bazely, Dawn R.; Tanentzap, Andrew J.; Voigt, Dennis R.; Da Silva, E. (2010). "Trillium grandiflorum height is an indicator of white-tailed deer density at local and regional scales". Forest Ecology and Management. 259 (8): 1472–1479. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.01.021.

- Case & Case (1997), p. 60.

- Lamoureux, Flore printanière, pp. 395, 441-443.

- Case & Case (1997), pp. 49,59.

- Bhattacharya, Surya (May 13, 2007). "'The herb true love of Canada': What you need to know about our now-blooming flower emblem, including the answer to the big question". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- Case & Case (1997), pp. 29-31,46-52.

- "Pamela Copeland Large-Flowered Trillium - Mt. Cuba Center". Mt. Cuba Center. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

- "Trillium grandiflorum". www.rhs.org. Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Niering, William A.; Olmstead, Nancy C. (1985) [1979]. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Eastern Region. Knopf. p. 611. ISBN 0-394-50432-1.

- Case, Jr., Frederick W. (Winter 1994). "Trillium grandiflorum: Doubles, Forms, and Diseases" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Rock Garden Society. 52 (1): 40–49.

- "Citizen science observations of Trillium species". iNaturalist. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Emblems and Symbols". Government of Ontario. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- "Ontario's provincial symbols". Government of Canada. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Ohio State Wildflower". Netstate. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- "Franco-Ontarian Flag". Ontario Office of Francophone Affairs. Archived from the original on 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- For examples see here or here.

Bibliography

- Case, Frederick W.; Case, Roberta B. (1997). Trilliums. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-374-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamoureux, Gisèle (2002). Flore Printanière (in French). Saint-Henri-de-Lévis, Quebec: Fleurbec. pp. 48, 429–449. ISBN 978-2-920174-15-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Biodiversity Information Serving Our Nation (BISON) occurrence data and maps for Trillium grandiflorum

- Citizen science observations for Large White Trillium at iNaturalist