Meerkat

The meerkat (Suricata suricatta) or suricate is a small mongoose and the only member of the genus Suricata. It lives in the Kalahari Desert in Botswana, in much of the Namib Desert in Namibia and southwestern Angola, and in South Africa. A group of meerkats is called a "mob", "gang" or "clan". A meerkat clan often consists of about 20 individuals, but some big clans have 50 or more members. In captivity, meerkats have an average life span of 12–14 years, and about 6–7 years in the wild.

| Meerkat | |

|---|---|

_Tswalu.jpg) | |

| A mob of meerkats in Tswalu Kalahari Reserve | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Herpestidae |

| Genus: | Suricata Desmarest, 1804 |

| Species: | S. suricatta |

| Binomial name | |

| Suricata suricatta (Schreber, 1776) | |

| |

| Meerkat range | |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

|

List

| |

Etymology

"Meerkat" is a loanword from Afrikaans (pronounced [ˈmɪərkat]).[5] The name is derived from Dutch, but by misidentification. In Dutch, meerkat means the guenon, a monkey of the genus Cercopithecus.[6] The word meerkat is Dutch for "lake cat".[7] the word possibly started as a Dutch adaptation of a derivative of Sanskrit markaṭa = "ape",[8] perhaps in Africa via an Indian sailor on board a Dutch East India Company ship.[9]

In early literature, the suricate was referred to as mierkat. In colloquial Afrikaans, mier means termite, and kat means cat. It has been suggested that the name refers to its association with termite mounds.[3]

Taxonomy

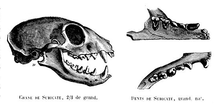

In 1776, Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber described a meerkat from the Cape of Good Hope, giving it the scientific name Viverra suricatta.[10] The generic name Suricata was proposed by Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest in 1804, who also described a zoological specimen from the same location.[11] The present scientific name, Suricata suricatta, was first used by zoologists Oldfield Thomas and Harold Schwann in 1905 when they described a specimen collected from Wakkerstroom. They suggested there were four local races of meerkats in the Cape and Deelfontein, Grahamstown, Orange River Colony and southern Transvaal, and Klipfontein respectively.[12] Several zoological specimens were described from the 18th to 20th centuries, of which three are recognized as valid subspecies:[3][4]

Physical characteristics

The meerkat is a small mongoose of slim build characterised by a broad head, large eyes, a pointed snout, long legs, a thin tapering tail and obscure, dark brown streaks on the back. It is smaller than most other mongooses except the dwarf mongooses (genus Helogale) and possibly Galerella species.[3] The head-and-body length is around 24–35 cm (9.4–13.8 in), and the weight has been recorded to be between 0.62–0.97 kg (1.4–2.1 lb). The soft coat is light gray to yellowish brown with alternate light and dark bands on the back. Individuals from the southern part of the range tend to be darker. The guard hairs, light at the base, have two dark rings and are tipped with black or silvery white; several such hairs aligned together form the brindled pattern.[3][15] These hairs are typically between 1.5 and 2 cm (0.59 and 0.79 in), but measure 3–4 cm (1.2–1.6 in) on the flanks. The head is mostly white and the underparts are covered sparsely with dark reddish brown fur.[3][16] The eyes, in sockets covering over 20% of the skull length, are capable of binocular vision.[3][17] The slim, yellowish tail, unlike the bushy tails of many other mongooses, measures 17 to 25 cm (6.7 to 9.8 in), and is tipped with black. Females have six nipples.[3]

The meerkat has 36 teeth; the dental formula is 3.1.3.23.1.3.2.[3] The physical design of the meerkat facilitates digging, movement through tunnels and standing erect, though it is not as capable of running and climbing. The big, sharp and curved foreclaws are highly specialized among the feliforms, and enable the meerkat to dig efficiently.[3][18] The black, crescent-like ears can be closed to prevent the entry of dirt and debris while digging. The tail is used to balance when standing upright, as well as for signaling. Digitigrade, the meerkat has long, narrow legs with four digits on the forefeet and five on the hind feet.[3]

Meerkats show a specialized thermoregulation system that helps them survive in their hot, arid habitat. A study showed that the body temperature of meerkats follows a diurnal rhythm, averaging 38.3 °C (100.9 °F) during the day and 36.3 °C (97.3 °F) at night. As the body temperature falls below the thermoneutral zone, determined to be 30–32.5 °C (86.0–90.5 °F) for meerkats, the heart rate and oxygen consumption plummet; perspiration increases sharply at temperatures above the zone. Meerkats additionally have a basal metabolic rate remarkably lower than other carnivores, which helps in conserving water and decreasing heat output from metabolic processes. During winter, the meerkat balances heat loss by increasing the metabolic heat generation and other methods such as sunbathing.[19][3]

Behaviour and ecology

Meerkats are small burrowing mammals, living in large underground networks with multiple entrances which they leave only during the day, except to avoid the heat of the afternoon.[20] They are very social creatures and they live in colonies together.[21] Animals in the same group groom each other regularly.[22] To look out for predators, one or more meerkats stand sentry, to warn others of approaching dangers.[23] When a predator is spotted, the meerkat performing as sentry gives a warning bark or whistle, and other members of the group run and hide in one of the many holes they have spread across their territory.[24]

Meerkats also babysit the young in the group. Females that have never produced offspring of their own often lactate to feed the alpha pair's young.[21] They also protect the young from threats, often endangering their own lives. On warning of danger, the babysitter takes the young underground to safety and is prepared to defend them if the danger follows.[25]

Meerkats are also known to share their burrow with the yellow mongoose and ground squirrel.[25] Like many species, meerkat young learn by observing and mimicking adult behaviour, though adults also engage in active instruction. For example, meerkat adults teach their pups how to eat a venomous scorpion: they will remove the stinger and help the pup learn how to handle the creature.[26]

Despite this altruistic behaviour, meerkats sometimes kill young members of their group. Subordinate meerkats have been seen killing the offspring of more senior members in order to improve their own offspring's position.[27]

When colonies are exposed to human presence for a long time, they will become habituated, which allows for documentation of their natural behavior. It is not unusual for camera crews, who must largely stay still for long periods while filming, to be utilized as convenient sentry posts.[28]

Vocalization

Meerkat calls may carry specific meanings, with particular calls indicating the type of predator and the urgency of the situation. In addition to alarm calls, meerkats also make panic calls, recruitment calls, and moving calls. They chirrup, trill, growl, or bark, depending on the circumstances.[29] Meerkats make different alarm calls depending upon whether they see an aerial or a terrestrial predator. Moreover, acoustic characteristics of the call will change with the urgency of the potential predatory episode. Therefore, six different predatory alarm calls with six different meanings have been identified: aerial predator with low, medium, and high urgency; and terrestrial predator with low, medium, and high urgency. Meerkats respond differently after hearing a terrestrial predator alarm call than after hearing an aerial predator alarm call. For example, upon hearing a high-urgency terrestrial predator alarm call, meerkats are most likely to seek shelter and scan the area. On the other hand, upon hearing a high-urgency aerial predator alarm call, meerkats are most likely to crouch down. On many occasions under these circumstances, they also look towards the sky to search for predators and any dangers that might harm the clan.[30]

Diet and foraging

_digging.jpg)

Meerkats are primarily insectivores, but also eat other animals (lizards, snakes, scorpions, spiders, eggs, small mammals, millipedes, centipedes and, more rarely, small birds), plants and the desert truffle Kalaharituber pfeilii.[31] Meerkats are immune to certain types of venom, including the very strong venom of the scorpions of the Kalahari Desert.[32]

Baby meerkats do not start foraging for food until they are about one month old, and they do so by following an older member of the group who acts as the pup's tutor.[33] Meerkats forage in a group with one sentry watching for predators while the others search for food. Sentry duty is usually approximately an hour long. The meerkat standing guard makes peeping sounds when all is well.[22]

A meerkat has the ability to dig through a quantity of sand equal to its own weight in just seconds. Digging is done to create burrows, to get food and also to create dust clouds to distract predators.[34]

Reproduction

Meerkats become sexually mature at about two years of age and can have one to four pups in a litter, with three pups being the most common litter size. Meerkats are iteroparous and can reproduce any time of the year.[21] The pups are allowed to leave the burrow at two to three weeks old.[35]

There is no precopulatory display; the male may fight with the female until she submits to him and copulation begins. Gestation lasts approximately 11 weeks and the young are born within the burrow and are altricial (undeveloped). The young's ears open at about 10 days of age, and their eyes at 10–14 days. They are weaned around 49 to 63 days.[21]

Usually, the alpha pair reserves the right to mate and normally kills any young not its own, to ensure that its offspring have the best chance of survival. The dominant couple may also evict the mothers of the offending offspring.[36] New meerkat groups are often formed by evicted females joining a group of males.[37]

Females appear to be able to discriminate the odour of their kin from the odour of their non-kin.[38] Kin recognition is a useful ability that facilitates cooperation among relatives and the avoidance of inbreeding. When mating does occur between meerkat relatives, it often results in negative fitness consequences or inbreeding depression. Inbreeding depression was evident for a variety of traits: pup mass at emergence from the natal burrow, hind-foot length, growth until independence and juvenile survival.[39] These negative effects are likely due to the increased homozygosity that arises from inbreeding and the consequent expression of deleterious recessive mutations. The avoidance of inbreeding and the promotion of outcrossing allow the masking of deleterious recessive mutations.[40] (Also see Complementation (genetics).)

Predators

Martial eagles, tawny eagles and jackals are the main predators of meerkats.[41] Meerkats sometimes die of snakebite in confrontations with snakes (puff adders and Cape cobras).[42]

Meerkats as pets

Meerkats, being wild animals, make poor pets. They can be aggressive, especially toward guests, and may bite. They will scent-mark their owner and the house (their "territory").[43]

See also

- Kalahari Meerkat Project, a long-term research project

- Meerkats in popular culture

- The Meerkats, a 2008 documentary feature film

References

- "Fossilworks: Suricata suricatta". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Jordan, N. R. & Do Linh San, E. (2015). "Suricata suricatta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T41624A45209377.

- Van Staaden, M. J. (1994). "Suricata suricatta" (PDF). Mammalian Species (483): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504085. JSTOR 3504085. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2016.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Genus Suricata". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Durkin, P. (2014). Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-19-166707-7.

- Aertsen, H.; Jeffers, R. J. (1993). "Plural formation in Afrikaans". Historical Linguistics 1989: Papers from the 9th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, New Brunswick, 14–18 August 1989. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 315. ISBN 9789027277053.

- New International Encyclopedia. 15. Dodd, Mead. 1916. p. 348.

- Harper, Douglas. "meerkat". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Mitrani, J. L. (2014). Psychoanalytic Technique and Theory: Taking the Transference. Karnac Books. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-78220-162-5.

- Schreber, J. C. D. (1776). "Viverra suricata". Die Säugethiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Erlangen: Expedition des Schreber'schen Säugthier- und des Esper'schen Schmetterlingswerkes. p. CVII.

- Desmarest, A. G. (1804). "Genre Surikate, Suricata Nob.". In Deterville, J. F. P. (ed.). Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle appliquée aux arts : principalement à l'agriculture et à l'économie rurale et domestique. 24. Paris: Deterville. p. 15.

- Thomas, O.; Sohwann, H. (1905). "The Rudd exploration of South Africa.—II. List of mammals from the Wakkerstroom district, south-eastern Transvaal". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 75 (1): 129–138. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1905.tb08370.x.

- Bradfield, R.D. (1936). "Description of new races of Kalahari birds and mammals". The Auk. 53 (1): 131–132. JSTOR 4077422.

- Crawford-Cabral, J. (1971). "A Suricata do Iona, subspécie nova" [Iona's meerkat, new subspecies]. Boletim do Instituto de Investigação Científica de Angola (in Portuguese). 8: 65–83.

- Hunter, L.; Barrett, P. (2018). A Field Guide to the Carnivores of the World (2nd ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4729-5080-2.

- Nowak, R. M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. pp. 219–221. ISBN 978-0-8018-8033-9.

- Miller, S. S. (2007). "Marvelous mammal eyes". All Kinds of Eyes. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 37–46. ISBN 978-0-7614-2519-9.

- Mares, M. A. (1999). "Meerkat". In Mares, M. A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Deserts. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-8061-3146-7.

- Müller, E. F.; Lojewski, U. (1986). "Thermoregulation in the meerkat (Suricata suricatta Schreber, 1776)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology. 83 (2): 217–224. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(86)90564-5.

- Rafferty, John P., ed. (2011). Carnivores. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-61530-385-4.

- "Suricata suricatta". animaldiversity.org.

- Ciovacco, Justine (2008). Meerkats. Gareth Stevens Pub. pp. 28, 37 ff. ISBN 978-0-8368-9098-3.

- Kalat, J. W. (2015). McElwain, H. (ed.). Biological Psychology. Cengage Learning. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-305-46529-9.

- Ganeri, Anita (2011). Nunn, Daniel; Rissman, Rebecca; Smith, Sian (eds.). Meerkat. Heinemann Library. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4329-4773-6.

- Moore, Heidi (2004). A Mob of Meerkats. Heinemann Library. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4034-4694-7.

- Thornton, Alex; McAuliffe, Katherine (2006). "Teaching in Wild Meerkats". Science. 313 (5784): 227–229. doi:10.1126/science.1128727. PMID 16840701.

- Norris, Scott (15 March 2006). "Murderous Meerkat Moms Contradict Caring Image, Study Finds". National Geographic News. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Magic Meerkat Moments". Planet Earth Live. BBC. 16 May 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Manser, Marta; Fletcher, Lindsay (2004). "Vocalize to Localize: A Test on Functionally Referential Alarm Calls". Interaction Studies. 5 (3): 327–344. doi:10.1075/is.5.3.02man.

- Manser, Marta B.; Bell, Matthew B.; Fletcher, Lindsay B. (7 December 2001). "The Information That Receivers Extract From Alarm Calls in Suricates". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 268 (1484): 2485–2491. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1772. PMC 1088904. PMID 11747568.

- Trappe, J. M.; Claridge, A. W.; Arora, D.; Smit, W. A. (2008). "Desert truffles of the Kalahari: ecology, ethnomycology and taxonomy". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 521–529. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9027-6.

- David Attenborough's World Of Wildlife 9 – Meerkats United (1999). Video

- "Mighty Masked Meerkat Mobs". Lifeinthefastlane.ca. 7 December 2007. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- "LadyWildLife". LadyWildLife. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- "Meerkat". zooatlanta.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Allman, Toney (2009). Animal Life in Groups. Infobase Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4381-2606-7.

- Armitage, Kenneth B. (2014). Marmot Biology: Sociality, Individual Fitness, and Population Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-139-99300-5.

- Leclaire S, Nielsen JF, Thavarajah NK, Manser M, Clutton-Brock TH (2013). "Odour-based kin discrimination in the cooperatively breeding meerkat". Biol. Lett. 9 (1): 20121054. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.1054. PMC 3565530. PMID 23234867.

- Nielsen JF, English S, Goodall-Copestake WP, Wang J, Walling CA, Bateman AW, Flower TP, Sutcliffe RL, Samson J, Thavarajah NK, Kruuk LE, Clutton-Brock TH, Pemberton JM (2012). "Inbreeding and inbreeding depression of early life traits in a cooperative mammal". Mol. Ecol. 21 (11): 2788–804. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05565.x. hdl:2263/19269. PMID 22497583.

- Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (1985). "Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex". Science. 229 (4719): 1277–1281. doi:10.1126/science.3898363. PMID 3898363.

- Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (2013). Mammals of Africa. A&C Black. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2.

- Skyrms, Brian (2010). Signals: Evolution, Learning, and Information. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-161490-3.

- "Meerkat adverts lead to surge in unwanted pets". BBC. 2010.

Further reading

- Macdonald, D. (1999). Meerkats. London: New Holland Publishers.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suricata suricatta. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Suricata suricatta |

- "Meerkat". Animal Diversity, University of Michigan.

- "Meerkat enquiries on the increase". BBC Nottingham. 2009.

- "Meerkat pups go to eating school". BBC News. 2006.