Great Lakes

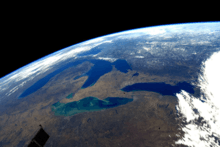

The Great Lakes (French: les Grands Lacs), or the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of interconnected freshwater lakes in the upper mid-east part of North America, on the Canada–United States border, which connect to the Atlantic Ocean through the Saint Lawrence River. They comprise Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario. Hydrologically, there are only four lakes, because Lakes Michigan and Huron join at the Straits of Mackinac. The lakes form the Great Lakes Waterway.

The Great Lakes are the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth by total area, and second-largest by total volume, containing 21% of the world's surface fresh water by volume.[1][2][3] The total surface is 94,250 square miles (244,106 km2), and the total volume (measured at the low water datum) is 5,439 cubic miles (22,671 km3),[4] slightly less than the volume of Lake Baikal (5,666 cu mi or 23,615 km3, 22–23% of the world's surface fresh water). Due to their sea-like characteristics (rolling waves, sustained winds, strong currents, great depths, and distant horizons) the five Great Lakes have also long been referred to as inland seas.[5] Lake Superior is the second-largest lake in the world by area, and the largest freshwater lake by surface area. Lake Michigan is the largest lake that is entirely within one country.[6][7][8][9]

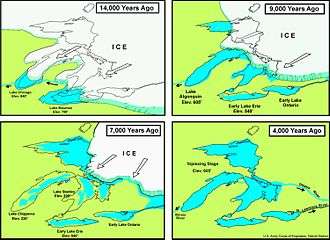

The Great Lakes began to form at the end of the last glacial period around 14,000 years ago, as retreating ice sheets exposed the basins they had carved into the land which then filled with meltwater.[10] The lakes have been a major source for transportation, migration, trade, and fishing, serving as a habitat to many aquatic species in a region with much biodiversity.

The surrounding region is called the Great Lakes region, which includes the Great Lakes Megalopolis.[11]

Geography

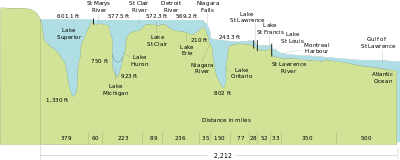

Though the five lakes lie in separate basins, they form a single, naturally interconnected body of fresh water, within the Great Lakes Basin. They form a chain connecting the east-central interior of North America to the Atlantic Ocean. From the interior to the outlet at the Saint Lawrence River, water flows from Superior to Huron and Michigan, southward to Erie, and finally northward to Lake Ontario. The lakes drain a large watershed via many rivers, and are studded with approximately 35,000 islands.[12] There are also several thousand smaller lakes, often called "inland lakes", within the basin.[13] The surface area of the five primary lakes combined is roughly equal to the size of the United Kingdom, while the surface area of the entire basin (the lakes and the land they drain) is about the size of the UK and France combined.[14] Lake Michigan is the only one of the Great Lakes that is entirely within the United States; the others form a water boundary between the United States and Canada. The lakes are divided among the jurisdictions of the Canadian province of Ontario and the U.S. states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. Both the province of Ontario and the state of Michigan include in their boundaries portions of four of the lakes: The province of Ontario does not border Lake Michigan, and the state of Michigan does not border Lake Ontario. New York and Wisconsin's jurisdictions extend into two lakes, and each of the remaining states into one of the lakes.

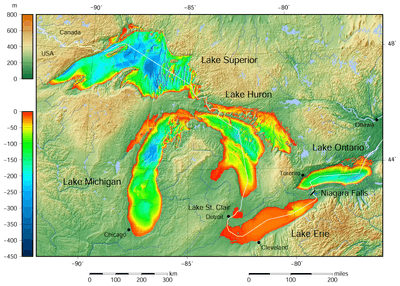

Bathymetry

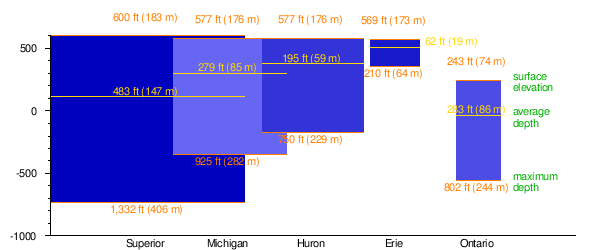

| |

| Notes: | The area of each rectangle is proportionate to the volume of each lake. All measurements at Low Water Datum. |

|---|---|

| Source: | EPA[15] |

| Lake Erie | Lake Huron | Lake Michigan | Lake Ontario | Lake Superior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area[4] | 9,910 sq mi (25,700 km2) | 23,000 sq mi (60,000 km2) | 22,300 sq mi (58,000 km2) | 7,340 sq mi (19,000 km2) | 31,700 sq mi (82,000 km2) |

| Water volume[4] | 116 cu mi (480 km3) | 850 cu mi (3,500 km3) | 1,180 cu mi (4,900 km3) | 393 cu mi (1,640 km3) | 2,900 cu mi (12,000 km3) |

| Elevation[15] | 571 ft (174 m) | 577 ft (176 m) | 577 ft (176 m) | 246 ft (75 m) | 600.0 ft (182.9 m) |

| Average depth[14] | 62 ft (19 m) | 195 ft (59 m) | 279 ft (85 m) | 283 ft (86 m) | 483 ft (147 m) |

| Maximum depth[16] | 210 ft (64 m) | 748 ft (228 m) | 925 ft (282 m) | 804 ft (245 m) | 1,333 ft (406 m) |

| Major settlements[17] | Buffalo, NY Erie, PA Cleveland, OH Lorain, OH Toledo, OH Sandusky, OH |

Alpena, MI Bay City, MI Owen Sound, ON Port Huron, MI Sarnia, ON |

Chicago, IL Gary, IN Green Bay, WI Sheboygan, WI Milwaukee, WI Kenosha, WI Racine, WI Muskegon, MI Traverse City, MI |

Hamilton, ON Kingston, ON Mississauga, ON Oshawa, ON Rochester, NY Toronto, ON |

Duluth, MN Marquette, MI Sault Ste. Marie, MI Sault Ste. Marie, ON Superior, WI Thunder Bay, ON |

As the surfaces of Lakes Superior, Huron, Michigan, and Erie are all approximately the same elevation above sea level, while Lake Ontario is significantly lower, and because the Niagara Escarpment precludes all natural navigation, the four upper lakes are commonly called the "upper great lakes". This designation is not universal. Those living on the shore of Lake Superior often refer to all the other lakes as "the lower lakes", because they are farther south. Sailors of bulk freighters transferring cargoes from Lake Superior and northern Lake Michigan and Lake Huron to ports on Lake Erie or Ontario commonly refer to the latter as the lower lakes and Lakes Michigan, Huron, and Superior as the upper lakes. This corresponds to thinking of lakes Erie and Ontario as "down south" and the others as "up north". Vessels sailing north on Lake Michigan are considered "upbound" even though they are sailing toward its effluent current.[24]

Primary connecting waterways

- The Chicago River and Calumet River systems connect the Great Lakes Basin to the Mississippi River System through man-made alterations and canals.

- The St. Marys River, including the Soo Locks, connects Lake Superior to Lake Huron.

- The Straits of Mackinac connect Lake Michigan to Lake Huron (which are hydrologically one).

- The St. Clair River connects Lake Huron to Lake St. Clair.

- The Detroit River connects Lake St. Clair to Lake Erie.

- The Niagara River, including Niagara Falls, connects Lake Erie to Lake Ontario.

- The Welland Canal, bypassing the Falls, connects Lake Erie to Lake Ontario.

- The Saint Lawrence River and the Saint Lawrence Seaway connect Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which connects to the Atlantic Ocean.

Lake Michigan–Huron

Lakes Huron and Michigan are sometimes considered a single lake, called Lake Michigan–Huron, because they are one hydrological body of water connected by the Straits of Mackinac.[25] The straits are five miles (8 km) wide[14] and 120 feet (37 m) deep; the water levels – currently at 577 feet (176 m) – rise and fall together,[26] and the flow between Michigan and Huron frequently reverses direction.

Large bays and related significant bodies of water

- Lake Nipigon, connected to Lake Superior by the Nipigon River, is surrounded by sill-like formations of mafic and ultramafic igneous rock hundreds of meters high. The lake lies in the Nipigon Embayment, a failed arm of the triple junction (centered beneath Lake Superior) in the Midcontinent Rift System event, estimated at 1,109 million years ago.

- Green Bay is an arm of Lake Michigan, along the south coast of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and the east coast of Wisconsin. It is separated from the rest of the lake by the Door Peninsula in Wisconsin, the Garden Peninsula in Michigan, and the chain of islands between them, all of which were formed by the Niagara Escarpment.

- Lake Winnebago, connected to Green Bay by the Fox River, serves as part of the Fox–Wisconsin Waterway and is part of a larger system of lakes in Wisconsin known as the Winnebago Pool.

- Grand Traverse Bay is an arm of Lake Michigan on Michigan's west coast, being one of the largest natural harbors in the Great Lakes. The bay has one large peninsula[27] and one major island known as Power Island. Its name is derived from Jacques Marquette's crossing of the bay from Norwood to Northport which he called La Grande Traversee.[28]

- Georgian Bay is an arm of Lake Huron, extending northeast from the lake entirely within Ontario. The bay, along with its narrow westerly extensions of the North Channel and Mississagi Strait, is separated from the rest of the lake by the Bruce Peninsula, Manitoulin Island, and Cockburn Island, all of which were also formed by the Niagara Escarpment.

- Lake Nipissing, connected to Georgian Bay by the French River, contains two volcanic pipes, which are the Manitou Islands and Callander Bay.[29] These pipes were formed by a violent, supersonic eruption of deep-origin. The lake lies in the Ottawa-Bonnechere Graben, a Mesozoic rift valley that formed 175 million years ago.

- Lake Simcoe, connected to Georgian Bay by the Severn River, serves as part of the Trent–Severn Waterway, a canal route traversing Southern Ontario between Lakes Ontario and Huron.

- Lake St. Clair, connected with Lake Huron to its north by the St. Clair River and with Lake Erie to its south by the Detroit River. Although it is 17 times smaller in area than Lake Ontario and only rarely included in the listings of the Great Lakes,[30][31] proposals for its official recognition as a Great Lake are occasionally made, which would affect its inclusion in scientific research projects, etc., designated as related to "The Great Lakes".[32]

- Saginaw Bay, an extension of Lake Huron into the lower peninsula of Michigan, fed by the Saginaw and other rivers, has the largest contiguous freshwater wetland in the United States.[33]

Islands

Dispersed throughout the Great Lakes are approximately 35,000 islands.[12] The largest among them is Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron, the largest island in any inland body of water in the world.[34] The second-largest island is Isle Royale in Lake Superior.[35] Both of these islands are large enough to contain multiple lakes themselves—for instance, Manitoulin Island's Lake Manitou is the world's largest lake on a freshwater island.[36] Some of these lakes even have their own islands, like Treasure Island in Lake Mindemoya in Manitoulin Island

Peninsulas

The Great Lakes also have several peninsulas between them, including the Door Peninsula, the Peninsulas of Michigan, and the Ontario Peninsula. Some of these peninsulas even contain smaller peninsulas, such as the Keweenaw Peninsula, the Thumb Peninsula, the Bruce Peninsula, and the Niagara Peninsula. Population centers on the peninsulas include Grand Rapids and Detroit in Michigan along with London, Hamilton, Brantford, and Toronto in Ontario.

Shipping connection to the ocean

Although the Saint Lawrence Seaway and Great Lakes Waterway make the Great Lakes accessible to ocean-going vessels,[37] shifts in shipping to wider ocean-going container ships—which do not fit through the locks on these routes—have limited container shipping on the lakes. Most Great Lakes trade is of bulk material, and bulk freighters of Seawaymax-size or less can move throughout the entire lakes and out to the Atlantic.[38] Larger ships are confined to working in the lakes themselves. Only barges can access the Illinois Waterway system providing access to the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi River. Despite their vast size, large sections of the Great Lakes freeze over in winter, interrupting most shipping from January to March. Some icebreakers ply the lakes, keeping the shipping lanes open through other periods of ice on the lakes.

The Great Lakes are also connected by the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal to the Gulf of Mexico by way of the Illinois River (from the Chicago River) and the Mississippi River. An alternate track is via the Illinois River (from Chicago), to the Mississippi, up the Ohio, and then through the Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway (a combination of a series of rivers and lakes and canals), to Mobile Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Commercial tug-and-barge traffic on these waterways is heavy.[39]

Pleasure boats can also enter or exit the Great Lakes by way of the Erie Canal and Hudson River in New York. The Erie Canal connects to the Great Lakes at the east end of Lake Erie (at Buffalo, New York) and at the south side of Lake Ontario (at Oswego, New York).

Water levels

In 2009, the lakes contained 84% of the surface freshwater of North America;[40] if the water were evenly distributed over the entire continent's land area, it would reach a depth of 5 feet (1.5 meters).[14] The source of water levels in the lakes is tied to what was left by melting glaciers when the lakes took their present form. Annually, only about 1% is "new" water originating from rivers, precipitation, and groundwater springs that drain into the lakes. Historically, evaporation has been balanced by drainage, making the level of the lakes constant.[14]

Intensive human population growth only began in the region in the 20th century and continues today.[14] At least two human water use activities have been identified as having the potential to affect the lakes' levels: diversion (the transfer of water to other watersheds) and consumption (substantially done today by the use of lake water to power and cool electric generation plants, resulting in evaporation).[41]

The physical impacts of climate change can be seen in water levels in the Great Lakes over the past century.[42] The United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1997, 23 years ago, predicted: "the following lake level declines could occur: Lake Superior −0.2 to −0.5 m, Lakes Michigan and Huron −1.0 to −2.5 m, and Lake Erie −0.9 to −1.9 m."[43] In 2009, 11 years ago, it was predicted that global warming will decrease water levels.[44] In 2013, record low water levels in the Great Lakes were attributed to climate change.[45]

The water level of Lake Michigan–Huron had remained fairly constant over the 20th century,[46] but has nevertheless dropped more than 6 feet from the record high in 1986 to the low of 2013.[47] In 2012, National Geographic tied the water level drop to warming climate change.,[48] as did the Natural Resources Defense Council.[49] One newspaper reported that the long-term average level has gone down about 20 inches because of dredging and subsequent erosion in the St. Clair River. Lake Michigan–Huron hit all-time record low levels in 2013; according to the US Army Corps of Engineers, the previous record low had been set in 1964.[47] By April 2015 the water level had recovered to 7 inches (17.5 cm) more than the "long term monthly average".[50]

Name origins

- Lake Erie

- From the Erie tribe, a shortened form of the Iroquoian word erielhonan "long tail".[51]

- Lake Huron

- Named for the inhabitants of the area, the Wyandot (or "Hurons"), by the first French explorers .[52] The Wyandot originally referred to the lake by the name karegnondi, a word which has been variously translated as "Freshwater Sea", "Lake of the Hurons", or simply "lake".[53][54]

- Lake Michigan

- From the Ojibwa word mishi-gami "great water" or "large lake".[55]

- Lake Ontario

- From the Wyandot (Huron) word ontarí'io "lake of shining waters".[56]

- Lake Superior

- English translation of the French term lac supérieur "upper lake", referring to its position north of Lake Huron. The indigenous Ojibwe call it gichi-gami (from Ojibwe gichi "big, large, great"; gami "water, lake, sea"). Popularized in French-influenced transliteration as Gitchigumi as in Gordon Lightfoot's 1976 story song "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald", or Gitchee Gumee as in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1855 epic poem, The Song of Hiawatha).[16]

Statistics

The Great Lakes contain 21% of the world's surface fresh water: 5,472 cubic miles (22,810 km3), or 6.0×1015 U.S. gallons, that is 6 quadrillion U.S gallons, (2.3×1016 liters). This is enough water to cover the 48 contiguous U.S. states to a uniform depth of 9.5 feet (2.9 m). Although the lakes contain a large percentage of the world's fresh water, the Great Lakes supply only a small portion of U.S. drinking water on a national basis.[57]

The total surface area of the lakes is approximately 94,250 square miles (244,100 km2)—nearly the same size as the United Kingdom, and larger than the U.S. states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire combined.[58]

The Great Lakes coast measures approximately 10,500 miles (16,900 km);,[14] but the length of a coastline is impossible to measure exactly and is not a well-defined measure (see Coastline paradox). Of the total 10,500 miles (16,900 km) of shoreline, Canada borders approximately 5,200 miles (8,400 km), while the remaining 5,300 miles (8,500 km) are bordered by the United States. Michigan has the longest shoreline of the United States, bordering roughly 3,288 miles (5,292 km) of shoreline, followed by Wisconsin (820 miles (1,320 km)), New York (473 miles (761 km)), and Ohio (312 miles (502 km)).[59] Traversing the shoreline of all the lakes would cover a distance roughly equivalent to travelling half-way around the world at the equator.[14]

Geology

It has been estimated that the foundational geology that created the conditions shaping the present day upper Great Lakes was laid from 1.1 to 1.2 billion years ago,[14][60] when two previously fused tectonic plates split apart and created the Midcontinent Rift, which crossed the Great Lakes Tectonic Zone. A valley was formed providing a basin that eventually became modern day Lake Superior. When a second fault line, the Saint Lawrence rift, formed approximately 570 million years ago,[14] the basis for Lakes Ontario and Erie were created, along with what would become the Saint Lawrence River.

The Great Lakes are estimated to have been formed at the end of the last glacial period (the Wisconsin glaciation ended 10,000 to 12,000 years ago), when the Laurentide Ice Sheet receded.[10] The retreat of the ice sheet left behind a large amount of meltwater (see Lake Algonquin, Lake Chicago, Glacial Lake Iroquois, and Champlain Sea) that filled up the basins that the glaciers had carved, thus creating the Great Lakes as we know them today.[61] Because of the uneven nature of glacier erosion, some higher hills became Great Lakes islands. The Niagara Escarpment follows the contour of the Great Lakes between New York and Wisconsin. Land below the glaciers "rebounded" as it was uncovered.[62] Since the glaciers covered some areas longer than others, this glacial rebound occurred at different rates.

A notable modern phenomenon is the formation of ice volcanoes over the lakes during wintertime. Storm-generated waves carve the lakes' ice sheet and create conical mounds through the eruption of water and slush. The process is only well-documented in the Great Lakes, and has been credited with sparing the southern shorelines from worse rocky erosion.[63]

Climate

The Great Lakes have a humid continental climate, Köppen climate classification Dfa (in southern areas) and Dfb (in northern parts)[64] with varying influences from air masses from other regions including dry, cold Arctic systems, mild Pacific air masses from the West, and warm, wet tropical systems from the south and the Gulf of Mexico.[65] The lakes themselves also have a moderating effect on the climate; they can also increase precipitation totals and produce lake effect snowfall.[64]

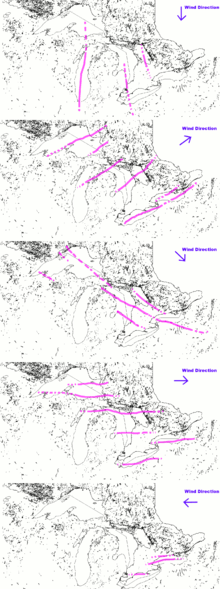

Lake effect

The Great Lakes can have an effect on regional weather called lake-effect snow, which is sometimes very localized. Even late in winter, the lakes often have no icepack in the middle. The prevailing winds from the west pick up the air and moisture from the lake surface, which is slightly warmer in relation to the cold surface winds above. As the slightly warmer, moist air passes over the colder land surface, the moisture often produces concentrated, heavy snowfall that sets up in bands or "streamers". This is similar to the effect of warmer air dropping snow as it passes over mountain ranges. During freezing weather with high winds, the "snow belts" receive regular snow fall from this localized weather pattern, especially along the eastern shores of the lakes. Snow belts are found in Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, United States; and Ontario, Canada.

The lakes also moderate seasonal temperatures to some degree, but not with as large an influence as do large oceans; they absorb heat and cool the air in summer, then slowly radiate that heat in autumn. They protect against frost during transitional weather, and keep the summertime temperatures cooler than further inland. This effect can be very localized and overridden by offshore wind patterns. This temperature buffering produces areas known as "Fruit Belts", where fruit can be produced that is typically grown much farther south. For instance, Western Michigan has apple and cherry orchards, and vineyards cultivated adjacent to the lake shore as far north as the Grand Traverse Bay and Nottawasaga Bay in central Ontario. The eastern shore of Lake Michigan and the southern shore of Lake Erie have many successful wineries because of the moderating effect, as does the Niagara Peninsula between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. A similar phenomenon allows wineries to flourish in the Finger Lakes region of New York, as well as in Prince Edward County, Ontario on Lake Ontario's northeast shore. Related to the lake effect is the regular occurrence of fog over medium-sized areas, particularly along the shorelines of the lakes. This is most noticeable along Lake Superior's shores.

The Great Lakes have been observed to help intensify storms, such as Hurricane Hazel in 1954, and the 2011 Goderich, Ontario tornado, which moved onshore as a tornadic waterspout. In 1996 a rare tropical or subtropical storm was observed forming in Lake Huron, dubbed the 1996 Lake Huron cyclone. Rather large severe thunderstorms covering wide areas are well known in the Great Lakes during mid-summer; these Mesoscale convective complexes or MCCs[66] can cause damage to wide swaths of forest and shatter glass in city buildings. These storms mainly occur during the night, and the systems sometimes have small embedded tornadoes, but more often straight-line winds accompanied by intense lightning.

Ecology

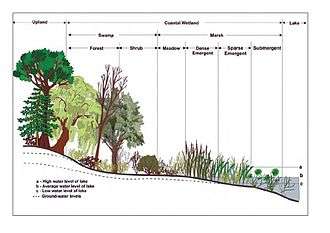

Historically, the Great Lakes, in addition to their lake ecology, were surrounded by various forest ecoregions (except in a relatively small area of southeast Lake Michigan where savanna or prairie occasionally intruded). Logging, urbanization, and agriculture uses have changed that relationship. In the early 21st century, Lake Superior's shores are 91% forested, Lake Huron 68%, Lake Ontario 49%, Lake Michigan 41%, and Lake Erie, where logging and urbanization has been most extensive, 21%. Some of these forests are second or third growth (i.e. they have been logged before, changing their composition). At least 13 wildlife species are documented as becoming extinct since the arrival of Europeans, and many more are threatened or endangered.[14] Meanwhile, exotic and invasive species have also been introduced.

Fauna

While the organisms living on the bottom of shallow waters are similar to those found in smaller lakes, the deep waters contain organisms found only in deep, cold lakes of the northern latitudes. These include the delicate opossum shrimp (order mysida), the deepwater scud (a crustacean of the order amphipoda), two types of copepods, and the deepwater sculpin (a spiny, large-headed fish).[68]

The Great Lakes are an important source of fishing. Early European settlers were astounded by both the variety and quantity of fish; there were 150 different species in the Great Lakes.[14] Throughout history, fish populations were the early indicator of the condition of the Lakes and have remained one of the key indicators even in the current era of sophisticated analyses and measuring instruments. According to the bi-national (U.S. and Canadian) resource book, The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book: "The largest Great Lakes fish harvests were recorded in 1889 and 1899 at some 67,000 tonnes (66,000 long tons; 74,000 short tons) [147 million pounds]."[69]

By 1801, the New York Legislature found it necessary to pass regulations curtailing obstructions to the natural migrations of Atlantic salmon from Lake Erie into their spawning channels. In the early 19th century, the government of Upper Canada found it necessary to introduce similar legislation prohibiting the use of weirs and nets at the mouths of Lake Ontario's tributaries. Other protective legislation was passed, as well, but enforcement remained difficult.[70]

On both sides of the Canada–United States border, the proliferation of dams and impoundments have multiplied, necessitating more regulatory efforts. Concerns by the mid-19th century included obstructions in the rivers which prevented salmon and lake sturgeon from reaching their spawning grounds. The Wisconsin Fisheries Commission noted a reduction of roughly 25% in general fish harvests by 1875. The states have removed dams from rivers where necessary.[71]

Overfishing has been cited as a possible reason for a decrease in population of various whitefish, important because of their culinary desirability and, hence, economic consequence. Moreover, between 1879 and 1899, reported whitefish harvests declined from some 24.3 million pounds (11 million kg) to just over 9 million pounds (4 million kg).[72] By 1900, commercial fishermen on Lake Michigan were hauling in an average of 41 million pounds of fish annually.[73] By 1938, Wisconsin's commercial fishing operations were motorized and mechanized, generating jobs for more than 2,000 workers, and hauling 14 million pounds per year.[73] The population of giant freshwater mussels was eliminated as the mussels were harvested for use as buttons by early Great Lakes entrepreneurs.[72] Since 2000, the invasive quagga mussel has smothered the bottom of Lake Michigan almost from shore to shore, and their numbers are estimated at 900 trillion.[73]

The influx of parasitic lamprey populations after the development of the Erie Canal and the much later Welland Canal led to the two federal governments of the US and Canada working on joint proposals to control it. By the mid-1950s, the lake trout populations of Lakes Michigan and Huron were reduced, with the lamprey deemed largely to blame. This led to the launch of the bi-national Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

.jpg)

The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book (1972) noted: "Only pockets remain of the once large commercial fishery."[69] But, water quality improvements realized during the 1970s and 1980s, combined with successful salmonid stocking programs, have enabled the growth of a large recreational fishery.[74] The last commercial fisherman left Milwaukee in 2011 because of overfishing and anthropogenic changes to the biosphere.[73]

Since the 19th century an estimated 160 new species have found their way into the Great Lakes ecosystem; many have become invasive; the overseas ship ballast and ship hull parasitism are causing severe economic and ecological impacts.[75][76] According to the Inland Seas Education Association, on average a new species enters the Great Lakes every eight months.[76]

Introductions into the Great Lakes include the zebra mussel, which was first discovered in 1988, and quagga mussel in 1989. The mollusks are efficient filter feeders, competing with native mussels and reducing available food and spawning grounds for fish. In addition, the mussels may be a nuisance to industries by clogging pipes. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that the economic impact of the zebra mussel could be about $5 billion over the next decade.[77]

The alewife first entered the system west of Lake Ontario via 19th-century canals. By the 1960s, the small silver fish had become a familiar nuisance to beach goers across Lakes Michigan, Huron, and Erie. Periodic mass dieoffs result in vast numbers of the fish washing up on shore; estimates by various governments have placed the percentage of Lake Michigan's biomass, which was made up of alewives in the early 1960s, as high as 90%. In the late 1960s, the various state and federal governments began stocking several species of salmonids, including the native lake trout as well as non-native chinook and coho salmon; by the 1980s, alewife populations had dropped drastically.[78] The ruffe, a small percid fish from Eurasia, became the most abundant fish species in Lake Superior's Saint Louis River within five years of its detection in 1986. Its range, which has expanded to Lake Huron, poses a significant threat to the lower lake fishery.[79] Five years after first being observed in the St. Clair River, the round goby can now be found in all of the Great Lakes. The goby is considered undesirable for several reasons: it preys upon bottom-feeding fish, overruns optimal habitat, spawns multiple times a season, and can survive poor water quality conditions.[80]

Several species of exotic water fleas have accidentally been introduced into the Great Lakes, such as the spiny waterflea, Bythotrephes longimanus, and the fishhook waterflea, Cercopagis pengoi, potentially having an effect on the zooplankton population. Several species of crayfish have also been introduced that may contend with native crayfish populations. More recently an electric fence has been set up across the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal in order to keep several species of invasive Asian carp out of the area. These fast-growing planktivorous fish have heavily colonized the Mississippi and Illinois river systems.[81] The sea lamprey, which has been particularly damaging to the native lake trout population, is another example of a marine invasive species in the Great Lakes.[82] Invasive species, particularly zebra and quagga mussels, may be at least partially responsible for the collapse of the deepwater demersal fish community in Lake Huron,[83] as well as drastic unprecedented changes in the zooplankton community of the lake.[84]

Microbiology

Scientists understand that the micro-aquatic life of the lakes is abundant, but know very little about some of the most plentiful microbes and their environmental effects in the Great Lakes. Although a drop of lake water may contain 1 million bacteria cells and 10 million viruses, only since 2012 has there been a long-term study of the lakes' micro-organisms. Between 2012 and 2019 more than 160 new species have been discovered.[85]

Flora

- See also: Flora of the Great Lakes region, and Index: Trees of the Great Lakes region.

Native habitats and ecoregions in the Great Lakes region include:

- Eastern forest-boreal transition

- Eastern Great Lakes lowland forests

- Southern Great Lakes forests

- Central forest-grasslands transition

- Upper Midwest forest-savanna transition

- Western Great Lakes forests

- Central Canadian Shield forests

- Laurentian Mixed Forest Province

- Beech-maple forest

- Habitats of the Indiana Dunes

Plant lists include:

- List of Michigan flowers

- List of Minnesota wild flowers

- List of Minnesota trees

Logging

Logging of the extensive forests in the Great Lakes region removed riparian and adjacent tree cover over rivers and streams, which provide shade, moderating water temperatures in fish spawning grounds. Removal of trees also destabilized the soil, with greater volumes washed into stream beds causing siltation of gravel beds, and more frequent flooding.

Running cut logs down the tributary rivers into the Great Lakes also dislocated sediments. In 1884, the New York Fish Commission determined that the dumping of sawmill waste (chips and sawdust) had impacted fish populations.[86]

Pollution

The first U.S. Clean Water Act, passed by a Congressional override after being vetoed by US President Richard Nixon in 1972, was a key piece of legislation,[87] along with the bi-national Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement signed by Canada and the U.S. A variety of steps taken to process industrial and municipal pollution discharges into the system greatly improved water quality by the 1980s, and Lake Erie in particular is significantly cleaner.[88] Discharge of toxic substances has been sharply reduced. Federal and state regulations control substances like PCBs. The first of 43 "Great Lakes Areas of Concern" to be formally "de-listed" due to successful cleanup was Ontario's Collingwood Harbour in 1994; Ontario's Severn Sound followed in 2003.[89] Presque Isle Bay in Pennsylvania is formally listed as in recovery, as is Ontario's Spanish Harbour. Dozens of other Areas of Concern have received partial cleanups such as the Rouge River (Michigan) and Waukegan Harbor (Illinois).[90]

Phosphate detergents were historically a major source of nutrient to the Great Lakes algae blooms in particular in the warmer and shallower portions of the system such as Lake Erie, Saginaw Bay, Green Bay, and the southernmost portion of Lake Michigan. By the mid-1980s, most jurisdictions bordering the Great Lakes had controlled phosphate detergents,[91] resulting in sharp reductions in the frequency and extent of the blooms.

Blue-green algae, or Cyanobacteria blooms,[92] have been problematic on Lake Erie since 2011.[93] "Not enough is being done to stop fertilizer and phosphorus from getting into the lake and causing blooms," said Michael McKay, executive director of the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research (GLIER) at the University of Windsor. The largest Lake Erie bloom to date occurred in 2015, exceeding the severity index at 10.5 and in 2011 at a 10.[94] In early August 2019, satellite images depicted a bloom stretching up to 1,300 square kilometres on Lake Erie, with the heaviest concentration near Toledo, Ohio. A large bloom does not necessarily mean the cyanobacteria ... will produce toxins", said Michael McKay, of the University of Windsor. Water quality testing was underway in August 2019.[95][94]

Mercury

Until 1970, mercury was not listed as a harmful chemical, according to the United States Federal Water Quality Administration. Within the past ten years mercury has become more apparent in water tests. Mercury compounds have been used in paper mills to prevent slime from forming during their production, and chemical companies have used mercury to separate chlorine from brine solutions. Studies conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency have shown that when the mercury comes in contact with many of the bacteria and compounds in the fresh water, it forms the compound methyl mercury, which has a much greater impact on human health than elemental mercury due to a higher propensity for absorption. This form of mercury is not detrimental to a majority of fish types, but is very detrimental to people and other wildlife animals who consume the fish. Mercury has been known for health related problems such as birth defects in humans and animals, and the near extinction of eagles in the Great Lakes region.[96]

Sewage

The amount of raw sewage dumped into the waters was the primary focus of both the first Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement and federal laws passed in both countries during the 1970s. Implementation of secondary treatment of municipal sewage by major cities greatly reduced the routine discharge of untreated sewage during the 1970s and 1980s.[97] The International Joint Commission in 2009 summarized the change: "Since the early 1970s, the level of treatment to reduce pollution from waste water discharges to the Great Lakes has improved considerably. This is a result of significant expenditures to date on both infrastructure and technology, and robust regulatory systems that have proven to be, on the whole, quite effective."[98] The commission reported that all urban sewage treatment systems on the U.S. side of the lakes had implemented secondary treatment, as had all on the Canadian side except for five small systems.

Though contrary to federal laws in both countries, those treatment system upgrades have not yet eliminated Combined sewer Overflow events. This describes when older sewerage systems, which combine storm water with sewage into single sewers heading to the treatment plant, are temporarily overwhelmed by heavy rainstorms. Local sewage treatment authorities then must release untreated effluent, a mix of rainwater and sewage, into local water bodies. While enormous public investments such as the Deep Tunnel projects in Chicago and Milwaukee have greatly reduced the frequency and volume of these events, they have not been eliminated. The number of such overflow events in Ontario, for example, is flat according to the International Joint Commission.[98] Reports about this issue on the U.S. side highlight five large municipal systems (those of Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, Milwaukee and Gary) as being the largest current periodic sources of untreated discharges into the Great Lakes.[99]

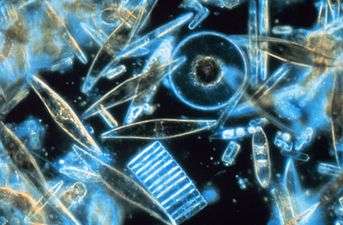

Impacts of climate change on algae

Algae such as diatoms, along with other phytoplankton, are photosynthetic primary producers supporting the food web of the Great Lakes,[100] and have been effected by global warming.[101] The changes in the size or in the function of the primary producers may have a direct or an indirect impact on the food web. Photosynthesis carried out by diatoms comprises about one fifth of the total photosynthesis. By taking CO

2 out of the water, to photosynthesize, diatoms help to stabilize the pH of the water, as otherwise CO

2 would react with water making it more acidic.

Diatoms acquire inorganic carbon thought passive diffusion of CO

2 and HCO3, as well they use carbonic anhydrase mediated active transport to speed up this process.[102] Large diatoms require more carbon uptake than smaller diatoms.[103] There is a positive correlation between the surface area and the chlorophyll concentration of diatom cells.[104]

History

Several Native American populations (Paleo-indians) inhabited the region around 10,000 BC, after the end of the Wisconsin glaciation.[105][106] The peoples of the Great Lakes traded with the Hopewell culture from around 1000 AD, as copper nuggets have been extracted from the region, and fashioned into ornaments and weapons in the mounds of Southern Ohio. The brigantine Le Griffon, which was commissioned by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, was built at Cayuga Creek, near the southern end of the Niagara River, and became the first known sailing ship to travel the upper Great Lakes on August 7, 1679.[107]

The Rush–Bagot Treaty signed in 1818, after the War of 1812 and the later Treaty of Washington eventually led to a complete disarmament of naval vessels in the Great Lakes. Nonetheless, both nations maintain coast guard vessels in the Great Lakes.

During settlement, the Great Lakes and its rivers were the only practical means of moving people and freight. Barges from middle North America were able to reach the Atlantic Ocean from the Great Lakes when the Welland canal opened in 1824 and the later Erie Canal opened in 1825.[108] By 1848, with the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal at Chicago, direct access to the Mississippi River was possible from the lakes.[109] With these two canals an all-inland water route was provided between New York City and New Orleans.

The main business of many of the passenger lines in the 19th century was transporting immigrants. Many of the larger cities owe their existence to their position on the lakes as a freight destination as well as for being a magnet for immigrants. After railroads and surface roads developed, the freight and passenger businesses dwindled and, except for ferries and a few foreign cruise ships, have now vanished. The immigration routes still have an effect today. Immigrants often formed their own communities and some areas have a pronounced ethnicity, such as Dutch, German, Polish, Finnish, and many others. Since many immigrants settled for a time in New England before moving westward, many areas on the U.S. side of the Great Lakes also have a New England feel, especially in home styles and accent.

Since general freight these days is transported by railroads and trucks, domestic ships mostly move bulk cargoes, such as iron ore, coal and limestone for the steel industry. The domestic bulk freight developed because of the nearby mines. It was more economical to transport the ingredients for steel to centralized plants rather than try to make steel on the spot. Grain exports are also a major cargo on the lakes.

In the 19th century and early 20th centuries, iron and other ores such as copper were shipped south on (downbound ships), and supplies, food, and coal were shipped north (upbound). Because of the location of the coal fields in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and the general northeast track of the Appalachian Mountains, railroads naturally developed shipping routes that went due north to ports such as Erie, Pennsylvania and Ashtabula, Ohio.

Because the lake maritime community largely developed independently, it has some distinctive vocabulary. Ships, no matter the size, are called boats. When the sailing ships gave way to steamships, they were called steamboats—the same term used on the Mississippi. The ships also have a distinctive design (see Lake freighter). Ships that primarily trade on the lakes are known as lakers. Foreign boats are known as salties. One of the more common sights on the lakes has been since about 1950 the 1,000‑by‑105-foot (305-by-32-meter), 78,850-long-ton (80,120-metric-ton) self-unloader. This is a laker with a conveyor belt system that can unload itself by swinging a crane over the side.[110] Today, the Great Lakes fleet is much smaller in numbers than it once was because of the increased use of overland freight, and a few larger ships replacing many small ones.

During World War II, the risk of submarine attacks against coastal training facilities motivated the United States Navy to operate two aircraft carriers on the Great Lakes, USS Sable (IX-81) and USS Wolverine (IX-64). Both served as training ships to qualify naval aviators in carrier landing and takeoff.[111] Lake Champlain briefly became the sixth Great Lake of the United States on March 6, 1998, when President Clinton signed Senate Bill 927. This bill, which reauthorized the National Sea Grant Program, contained a line declaring Lake Champlain to be a Great Lake. Not coincidentally, this status allows neighboring states to apply for additional federal research and education funds allocated to these national resources.[112] Following a small uproar, the Senate voted to revoke the designation on March 24 (although New York and Vermont universities would continue to receive funds to monitor and study the lake).[113]

In the early years of the 21st century, water levels in the Great Lakes were a concern.[114] Researchers at the Mowat Centre said that low levels could cost $19bn by 2050.[115]

Economy

Fishing

Alan B. McCullough has written that the fishing industry of the Great Lakes got its start "on the American side of Lake Ontario in Chaumont Bay, near the Maumee River on Lake Erie, and on the Detroit River at about the time of the War of 1812." Although the region was sparsely populated until the 1830s, so there was not much local demand and transporting fish was still prohibitively costly, there were economic and infrastructure developments that were promising for the future of the fishing industry going into the 1830s. Particularly, the 1825 opening of the Erie Canal and the Welland Canal a few years later. The fishing industry expanded particularly in the waters associated with the fur trade that connect Lake Erie and Lake Huron. In fact, two major suppliers of fish in the 1830s were the fur trading companies Hudson's Bay Company and the American Fur Company.[116]

The catch from these waters would be sent to the growing market for salted fish in Detroit, where merchants involved in the fur trade had already gained some experience handling salted fish. One such merchant was John P. Clark, a shipbuilder and merchant who began selling fish in the area of Manitowoc, Wisconsin where whitefish was abundant. Another operation cropped up in Georgian Bay, Canadian waters plentiful with trout as well as whitefish. In 1831, Alexander MacGregor from Goderich, Ontario found whitefish and herring in unusually abundant supply around the Fishing Islands. A contemporary account by Methodist missionary John Evans describes the fish as resembling a "bright cloud moving rapidly through the water".[116]

Shipping

Except when the water is frozen during winter, more than 100 lake freighters operate continuously on the Great Lakes,[117] which remain a major water transport corridor for bulk goods. The Great Lakes Waterway connects all the lakes; the smaller Saint Lawrence Seaway connects the lakes to the Atlantic oceans. Some lake freighters are too large to use the Seaway, and operate only on the Waterway and lakes.

In 2002, 162 million net tons of dry bulk cargo were moved on the Lakes. This was, in order of volume: iron ore, grain and potash.[118] The iron ore and much of the stone and coal are used in the steel industry. There is also some shipping of liquid and containerized cargo but most container ships cannot pass the locks on the Saint Lawrence Seaway because the ships are too wide.

Only four bridges are on the Great Lakes other than Lake Ontario because of the cost of building structures high enough for ships to pass under. The Blue Water Bridge is, for example, more than 150 feet high and more than a mile long.[117]

Major ports on the Great Lakes include Duluth-Superior, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Twin Harbors, Hamilton and Thunder Bay.

Drinking water and compact

The Great Lakes are used to supply drinking water to tens of millions of people in bordering areas. This valuable resource is collectively administered by the state and provincial governments adjacent to the lakes, who have agreed to the Great Lakes Compact to regulate water supply and use.

Recreation

Tourism and recreation are major industries on the Great Lakes.[119] A few small cruise ships operate on the Great Lakes including a couple of sailing ships. Sport fishing, commercial fishing, and Native American fishing represent a U.S.$4 billion a year industry with salmon, whitefish, smelt, lake trout, bass and walleye being major catches. Many other water sports are practiced on the lakes such as yachting, sea kayaking, diving, kitesurfing, powerboating, and lake surfing.

The Great Lakes Circle Tour is a designated scenic road system connecting all of the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River.[120]

Great Lakes passenger steamers

From 1844 through 1857, palace steamers carried passengers and cargo around the Great Lakes.[121] In the first half of the 20th century large luxurious passenger steamers sailed the lakes in opulence.[122] The Detroit and Cleveland Navigation Company had several vessels at the time and hired workers from all walks of life to help operate these vessels.[123] Several ferries currently operate on the Great Lakes to carry passengers to various islands, including Isle Royale, Drummond Island, Pelee Island, Mackinac Island, Beaver Island, Bois Blanc Island (Ontario), Bois Blanc Island (Michigan), Kelleys Island, South Bass Island, North Manitou Island, South Manitou Island, Harsens Island, Manitoulin Island, and the Toronto Islands. As of 2007, four car ferry services cross the Great Lakes, two on Lake Michigan: a steamer from Ludington, Michigan, to Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and a high speed catamaran from Milwaukee to Muskegon, Michigan, one on Lake Erie: a boat from Kingsville, Ontario, or Leamington, Ontario, to Pelee Island, Ontario, then onto Sandusky, Ohio, and one on Lake Huron: the M.S. Chi-Cheemaun [124] runs between Tobermory and South Baymouth, Manitoulin Island, operated by the Owen Sound Transportation Company. An international ferry across Lake Ontario from Rochester, New York, to Toronto ran during 2004 and 2005, but is no longer in operation.

Shipwrecks

The large size of the Great Lakes increases the risk of water travel; storms and reefs are common threats. The lakes are prone to sudden and severe storms, in particular in the autumn, from late October until early December. Hundreds of ships have met their end on the lakes. The greatest concentration of shipwrecks lies near Thunder Bay (Michigan), beneath Lake Huron, near the point where eastbound and westbound shipping lanes converge.

The Lake Superior shipwreck coast from Grand Marais, Michigan, to Whitefish Point became known as the "Graveyard of the Great Lakes". More vessels have been lost in the Whitefish Point area than any other part of Lake Superior.[125] The Whitefish Point Underwater Preserve serves as an underwater museum to protect the many shipwrecks in this area.

The first ship to sink in Lake Michigan was Le Griffon, also the first ship to sail the Great Lakes. Caught in a 1679 storm while trading furs between Green Bay and Michilimacinac, she was lost with all hands aboard.[126] Its wreck may have been found in 2004,[127] but a wreck subsequently discovered in a different location was also claimed in 2014 to be Le Griffon.[128]

The largest and last major freighter wrecked on the lakes was the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank on November 10, 1975, just over 17 miles (30 km) offshore from Whitefish Point on Lake Superior. The largest loss of life in a shipwreck out on the lakes may have been that of Lady Elgin, wrecked in 1860 with the loss of around 400 lives on Lake Michigan. In an incident at a Chicago dock in 1915, the SS Eastland rolled over while loading passengers, killing 841.

In August 2007, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society announced that it had found the wreckage of Cyprus, a 420-foot (130 m) long, century-old ore carrier. Cyprus sank during a Lake Superior storm on October 11, 1907, during its second voyage while hauling iron ore from Superior, Wisconsin, to Buffalo, New York. The entire crew of 23 drowned, except one, Charles Pitz, who floated on a life raft for almost seven hours.[129]

In June 2008, deep sea divers in Lake Ontario found the wreck of the 1780 Royal Navy warship HMS Ontario in what has been described as an "archaeological miracle".[130] There are no plans to raise her as the site is being treated as a war grave.

In June 2010, L.R. Doty was found in Lake Michigan by an exploration diving team led by dive boat Captain Jitka Hanakova from her boat the Molly V.[131] The ship sank in October 1898, probably attempting to rescue a small schooner, Olive Jeanette, during a terrible storm.

Still missing are the two last warships to sink in the Great Lakes, the French minesweepers, Inkerman and Cerisoles, which vanished in Lake Superior during a blizzard in 1918. 78 lives were lost making it the largest loss of life in Lake Superior and the greatest unexplained loss of life in the Great Lakes.

Related articles

- List of shipwrecks in the Great Lakes

- Index: Shipwrecks in the Great Lakes

- Great Storms of the North American Great Lakes

- Great Lakes Storm of 1913

Legislation

In 1872, a treaty gave access to the St. Lawrence River to the United States, and access to Lake Michigan to the Dominion of Canada.[132] The International Joint Commission was established in 1909 to help prevent and resolve disputes relating to the use and quality of boundary waters, and to advise Canada and the United States on questions related to water resources. Concerns over diversion of Lake water are of concern to both Americans and Canadians. Some water is diverted through the Chicago River to operate the Illinois Waterway but the flow is limited by treaty. Possible schemes for bottled water plants and diversion to dry regions of the continent raise concerns. Under the U.S. "Water Resources Development Act",[133] diversion of water from the Great Lakes Basin requires the approval of all eight Great Lakes governors through the Great Lakes Commission, which rarely occurs. International treaties regulate large diversions.

In 1998, the Canadian company Nova Group won approval from the Province of Ontario to withdraw 158,000,000 U.S. gallons (600,000 m3) of Lake Superior water annually to ship by tanker to Asian countries. Public outcry forced the company to abandon the plan before it began. Since that time, the eight Great Lakes Governors and the Premiers of Ontario and Quebec have negotiated the Great Lakes-Saint Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement[134] and the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact[135] that would prevent most future diversion proposals and all long-distance ones. The agreements strengthen protection against abusive water withdrawal practices within the Great Lakes basin. On December 13, 2005, the Governors and Premiers signed these two agreements, the first of which is between all ten jurisdictions. It is somewhat more detailed and protective, though its legal strength has not yet been tested in court. The second, the Great Lakes Compact, has been approved by the state legislatures of all eight states that border the Great Lakes as well as the U.S. Congress, and was signed into law by President George W. Bush on October 3, 2008.[136]

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, described as "the largest investment in the Great Lakes in two decades",[137] was funded at $475 million in the U.S. federal government's Fiscal Year 2011 budget, and $300 million in the Fiscal Year 2012 budget. Through the program a coalition of federal agencies is making grants to local and state entities for toxics cleanups, wetlands and coastline restoration projects, and invasive species-related projects.

See also

- Alliance for the Great Lakes

- Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909

- Eastern Continental Divide

- Great Lakes census statistical areas

- Great Lakes Megalopolis

- Great Lakes Protection Fund

- Great Lakes WATER Institute

- Great Lakes Waterway

- Great Recycling and Northern Development Canal

- List of cities on the Great Lakes

- List of municipalities on the Great Lakes

- Michigan Islands National Wildlife Refuge

- Muskellunge

- Northern pike

- Populated islands of the Great Lakes

- Seiche

- Snowbelt

- Sixty Years' War for control of the Great Lakes

- Valparaiso Moraine

References

- "Great Lakes". US Epa.gov. June 28, 2006. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "LUHNA Chapter 6: Historical Landcover Changes in the Great Lakes Region". Biology.usgs.gov. November 20, 2003. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- Ghassemi, Fereidoun (2007). Inter-basin water transfer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86969-0.

- "Great Lakes: Basic Information: Physical Facts". United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). May 25, 2011. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- Williamson, James (2007). The inland seas of North America: and the natural and industrial productions ... John Duff Montreal Hew Ramsay Toronto AH Armour and Co. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "The Top Ten: The Ten Largest Lakes of the World". infoplease.com.

- Rosenberg, Matt. "Largest Lakes in the World by Area, Volume and Depth". About.com Education.

- Hough, Jack (1970) [1763]. "Great Lakes". The Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (Commemorative Edition for Expo'70 ed.). Chicago: William Benton. p. 774. ISBN 978-0-85229-135-1.

- "Large Lakes of the World". factmonster.com.

- Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- Great Lakes. America 2050. Retrieved on December 7, 2016.

- Tom Bennett (1999). State of the Great Lakes: 1997 Annual Report. Diane Publishing. p. 1991. ISBN 978-0-7881-4358-8.

- Likens, Gene E. (2010). Lake Ecosystem Ecology: A Global Perspective. Academic Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-12-382003-7.

- Grady, Wayne (2007). The Great Lakes. Vancouver: Greystone Books and David Suzuki Foundation. pp. 13, 21–26, 42–43. ISBN 978-1-55365-197-0.

- "Great Lakes Atlas: Factsheet #1". United States Environmental Protection Agency. March 9, 2006. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- "Great Lakes Map". Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on November 14, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- See List of cities on the Great Lakes for a complete list.

- National Geophysical Data Center (1999). Bathymetry of Lake Erie and Lake Saint Clair. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5KS6PHK

- National Geophysical Data Center (1999). Bathymetry of Lake Huron. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5G15XS5

- National Geophysical Data Center (1999). Bathymetry of Lake Michigan. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5B85627

- National Geophysical Data Center (1999). Bathymetry of Lake Ontario. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V56H4FBH

- National Geophysical Data Center (1999). Bathymetry of Lake Superior. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA.

(the general reference to NGDC because this lake was never published, compilation of Great Lakes Bathymetry at NGDC has been suspended). - National Geophysical Data Center (1999). Global Land One-kilometer Base Elevation (GLOBE) v. 1. Hastings, D. and P.K. Dunbar. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V52R3PMS

- W. Bruce Bowlus (2010). Iron Ore Transport on the Great Lakes: The Development of a Delivery System to Feed American Industry. McFarland. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7864-8655-7.

- "Michigan and Huron: One Lake or Two?" Pearson Education, Inc: Information Please Database, 2007.

- Wright, John W., ed. (2006). The New York Times Almanac (2007 ed.). New York: Penguin Books. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-14-303820-7.

- Home. Peninsula Township. Retrieved on December 7, 2016.

- Citation needed|May 2016

- Background Geology of the North Bay area. Archived July 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on September 24, 2007

- Lake St. Clair summary report Archived April 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Great Lakes.net. Retrieved on December 2, 2007.

- "Chapter 1:Introduction to Lake St. Clair and the St. Clair River". U.S. government U.S. Army. June 2004. Archived from the original on January 10, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- "Movement Would Thrust Greatness on Lake St. Clair", Los Angeles Times, October 20, 2002

- https://www.epa.gov/greatlakes

- Dunn, Gary A (July 1, 1996). Insects of the Great Lakes Region. University of Michigan Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-472-06515-8.

- Huber, Norman King; Geological Survey (U.S.); United States. National Park Service (1975). The geologic story of Isle Royale National Park. Department of the Interior, Geological Survey: for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 41.

- Manivanan, R. (January 1, 2008). Water Quality Modeling: Rivers, Streams, and Estuaries. New India Publishing. p. 114. ISBN 978-81-89422-93-6.

- Robert McCalla (January 1, 1994). Water Transportation in Canada. Formac Publishing Company. pp. 159–162. ISBN 978-0-88780-247-8.

- Coastal Sediments '07. ASCE Publications. January 1, 2007. p. 2215. ISBN 978-0-7844-7194-4. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- United States. Bureau of the Census (1908). Transportation by water. 1906. Govt. Print. Off. p. 220.

- "The Great Lakes". US EPA. August 20, 2015.

- "State of the Great Lakes 2009 Highlights (PDF)". Environment Canada and USEPA. pp. 7–8. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Thomas Dietz; David Bidwell (December 1, 2011). Climate Change in the Great Lakes Region: Navigating an Uncertain Future. MSU Press. ISBN 978-1-60917-236-7.

- Robert Watson; Marufu Zinyowera; Richard Moss (1997). "The Regional Impacts of Climate Change". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. United Nations. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

the following lake level declines could occur: Lake Superior −0.2 to −0.5 m, Lakes Michigan and Huron −1.0 to −2.5 m, and Lake Erie −0.9 to −1.9 m

- Bruce Elliott Johansen (2009). The Encyclopedia of Global Warming Science and Technology. p. 299. ISBN 978-0313377020. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

A warming climate for inland lakes (notably the Great Lakes of North America) generally will not raise water levels, as in the oceans, but rather decrease water levels.

- Dan Kraker (April 23, 2013). "Great Lakes water levels reaching record lows". Minnesota Public Radio. Archived from the original on February 5, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Scientists at the Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is studying the interplay between low water levels, shrinking ice cover and warm water temperatures, Gronewold said. They have already concluded that climate change is playing a role in determining Great Lakes water levels. "More recently, evaporation over lakes has steadily been increasing, largely due to increases in water surface temperature," Gronewold said. "That's a climate response

- Bolsenga, Stanley J.; Herdendorf, Charles E. (1993). Lake Erie and Lake Saint Clair Handbook. Wayne State University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8143-2470-7.

- jsonline.com: Lakes Michigan, Huron hit record low water level February 5, 2013

- Lisa Borre (November 20, 2012). "Warming Lakes: Climate Change and Variability Drive Low Water Levels on the Great Lakes". National Geographic. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Low water levels are not the only climate-related trend being observed on the Great Lakes.

- Aliya Haq. "Climate change is lowering Great Lakes water levels. Should Waukesha be allowed to tap into the Lakes?". NRDC. Archived from the original on February 10, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- "Weekly Great Lakes Water Level Update"; Detroit District, Corps of Engineers, Department of the Army (April 17, 2005)

- Room, A. (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins And Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features And Historic Sites. McFarland. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Room, A. (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins And Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features And Historic Sites. McFarland. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Sioui, Georges E. (1999). Huron-Wendat. Jane Brierley. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0715-9. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- Fonger, Ron (May 3, 2007). "Genesee, Oakland counties adopt historic name for water group". The Flint Journal. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- Weiland, Matt; Wilsey, Sean (October 19, 2010). State by State. HarperCollins. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-06-204357-3.

- Ylvisaker, Anne (2004). Lake Ontario. Capstone. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7368-2211-4.

- Cayton, Andrew R.L.; Sisson, Richard; Zacher, Chris (November 8, 2006). The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-253-00349-2.

- Taylor, William W.; Schechter, Michael G.; Wolfson, Lois G. (2007). Globalization: Effects on Fisheries Resources. Cambridge University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-139-46834-3.

- "Shorelines of the Great Lakes". Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- Van Schmus, W.R.; Hinze, W. J. (May 1985). "The Midcontinent Rift System" (PDF). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 13 (1): 345–83. Bibcode:1985AREPS..13..345V. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.13.050185.002021. hdl:1808/104. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- Larson, Grahame; Schaetzl, R. (2001). "Origin and evolution of the Great Lakes" (PDF). Journal of Great Lakes Research. 27 (4): 518–546. doi:10.1016/S0380-1330(01)70665-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- "Lake levels report weighs Great Lakes basin's glacial legacy". Great Lakes Echo. June 8, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- Fahnestock, R. K.; Crowley, D. J.; Wilson, M.; Schneider, H. (1973). "Ice Volcanoes of the Lake Erie Shore Near Dunkirk, New York, U.S.A." (PDF). Journal of Glaciology. 12 (64): 93–99. doi:10.3189/S0022143000022735. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- "Natural Processes in the Great Lakes". The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book. Environmental Protection Agency. July 24, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- "Great Lakes Water Levels Sensitive To Climate Change". Science Daily. January 14, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- "Glossary". NOAA's National Weather Service.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. "Great Lakes Lake Sturgeon Web Site". fws.gov.

- Beeton, Alfred. "Great Lakes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- Anon (1972). The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book. Bi-national (U.S. and Canadian) resource book.

- Margaret Beattie Bogue (2001). Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783–1933. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-299-16763-9.

- Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. Special report ... of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. The Commission. p. 23.

- Macdonald, David; Service, Katrina, eds. (2009). Key Topics in Conservation Biology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4443-0906-5.

- The lake left me. It's gone., JS Online, August 13, 2011

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (1998). EPA, Great Minds?, Great Lakes!, Lake Guardian, Don't Miss The Boat With Environmental Education, March 1997. s.n. p. 7.

- "New EPA rules to target invasive species; Invaders have plagued Great Lakes for years". The Blade. ProQuest 380761083.

- "Our Threatened Great Lakes". Inland Seas Education Association. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- "Great Lakes Aquatic Nuisance Species". Great Lakes Commission. March 27, 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- Smith, Paul (February 24, 2009). "Gobies up, alewives down in Lake Michigan". Journal Sentinel. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- "Predicting Invasive Species in the Great Lakes". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- Glassner-Shwayder, Katherine (July 2000). "Briefing Paper: Great Lakes Nonindigenous Invasive Species" (PDF). Great Lakes Nonindigenous Invasive Species Workshop. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2005. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- "Asian Carp Risk Assessment for Canada by Fisheries and Oceans Canada" (PDF). CSAS. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- "Petromyzon marinus Linnaeus 1758". USGS. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- Riley, S.C.; Roseman, Edward F.; Nichols, S. Jerrine; O'Brien, Timothy P.; Kiley, Courtney S.; Schaeffer, Jeffrey S. (2008). "Deepwater demersal fish community collapse in Lake Huron" (PDF). Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 137 (6): 1879–90. doi:10.1577/T07-141.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2013.

- Barbiero, R. P.; Barbiero, Richard P.; Balcer, Mary; Rockwell, David C.; Tuchman, Marc L. (2009). "Recent shifts in the crustacean zooplankton community of Lake Huron". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 66 (5): 816–828. doi:10.1139/F09-036.

- Briscoe, Tony (July 5, 2019). "Minuscule microbes wield enormous power over the Great Lakes. But many species remain a mystery". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- Dempsey, Dave (2004). On the Brink: The Great Lakes in the 21st Century. Michigan State University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-87013-705-1.

- "Evolution of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement", Paul Muldoon and Lee Botts, Michigan State University Press, 2005

- Recovery of Lake Erie Walleye a Success Story. Department of Natural Resources State of Michigan, U.S. (June 8, 2006)

- "Our Great Lakes" (PDF). binational.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2005.

- Milestone in Waukegan Harbor PCB Cleanup. Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. (Spring 1997)

- Knud-Hansen, Chris (February 1994) Historical Perspecivie Of The Phosphate Detergent Conflict Archived May 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Working Paper 94-54. Colorado.edu. Retrieved on December 7, 2016.

- https://www.weather.gov/cle/LakeErieHAB, Lake Erie Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB)

- Spring Rain, Then Foul Algae in Ailing Lake Erie March 14, 2013 New York Times

- https://windsorstar.com/news/local-news/large-lake-erie-algal-bloom-nearing-colchester-tested-for-toxicity Archived August 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Large Lake Erie algal bloom nearing Colchester tested for toxicity

- http://www.uwindsor.ca/dailynews/2019-08-07/uwindsor-researchers-test-waters-harmful-algae-bloom Archived August 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, UWindsor researchers test the waters for harmful algae bloom

- "Mercury Spills". Idph.state.il.us. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- "Lake Erie Water Quality Past Present and Future" (PDF). Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- "14th Biennial Report on Great Lakes Water Quality" (PDF).

- New Report: Solving Region's Sewage Crisis Will Create Jobs, Restore Great Lakes. Healthylakes.org (August 9, 2010). Retrieved on December 7, 2016.

- "Great Lakes". GLC.

- Williams, Kurt (February 13, 2019). "Monitoring algal blooms in the Great Lakes Basin". Great Lakes Echo.

- Burkhardt Steffen, Amoroso Gabi, Riebesell Ulf, Sültemeyer Dieter, (2001), CO2 and HCO3 ߚ uptake in marine diatoms acclimated to different CO2 concentrations, Limnology and Oceanography, 6, doi:10.4319/lo.2001.46.6.1378.

- Brian N. Popp, Edward A. Laws, Robert R. Bidigare, John E. Dore, et al., Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, (1998), Effect of Phytoplankton Cell Geometry on Carbon Isotopic Fractionation, Vol. 62, Iss. pp. 69-77.

- Durbin, E.G. (1977), "Studies on the Autecology of the Marine Diatom Thalassonira Nordenskioedill II. The Influence of Cell Size on Growth Rate, and Carbon, Nitrogen, Chlorophil a and Silica Content". Journal of Phycology, 13: 150–155.

- O'Shea, John; Meadows, Guy (June 23, 2009). "Evidence for early hunters beneath the Great Lakes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (25): 10120–10123. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902785106. PMC 2700903. PMID 19506245.

The earliest human occupation in the upper Great Lakes is associated with the regional fluted-point Paleoindian tradition, which conventionally ends with the drop in water level to the Lake Stanley stage

- "Ancient Land and First Peoples". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- Woodford, Arthur M. (1991). Charting the Inland Seas: A History of the U.S. Lake Survey. Wayne State University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8143-2499-8.

- Bernstein, Peter L. (2010). Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation. W.W. Norton. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-393-32795-3.

- Danzer, Gerald A. (2011). Illinois: A History in Pictures. University of Illinois Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-252-03288-2.

- Wharton, George. "Great Lakes Fleet Page Vessel Feature – Burns Harbor". Boatnerd. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- Gonzalez, Therese (2008). Great Lakes Naval Training Station. Arcadia Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7385-5193-7.

- Lake Champlain, The Sixth Great Lake? – Geography – 03/02/98. Geography.about.com (March 6, 1998). Retrieved on July 12, 2013.

- Seelye, Katharine Q. (March 25, 1998). "Lakes Are Born Great, 5 Sniff, So Upstart Is Ousted". The New York Times. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- Julie Bosman. "G+M: "Creeping up on unsuspecting shores: The Great Lakes" 28 Jun 2014". Theglobeandmail.com. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- "Great Lakes low water levels could cost $19B by 2050". cbc.ca. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- Bogue, Magaret Beattie (2000). Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783-1933. The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 29–31.

- "Chapter 4: The Watery Boundary". United Divide: A Linear Portrait of the USA/Canada Border. The Center for Land Use Interpretation. Winter 2015.

- "Great Lake Seaway Cargoes – American Great Lakes Ports Association". www.greatlakesports.org.

- Grover, Velma I.; Krantzberg, Gail (2012). Great Lakes: Lessons in Participatory Governance. CRC Press. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-57808-769-3.

- "Great Lakes Circle Tour". Great-lakes.net. July 5, 2005. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- Thompson, Mark L. (1991). Steamboats & Sailors of the Great Lakes. Wayne State University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8143-2359-5.

- Strand, Kathryn Koutsky; Koutsky, Linda (2006). Minnesota Vacation Days: An Illustrated History. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-87351-526-9.

- Toast of the Town: The Life and Times of Sunnie Wilson. Wayne State University Press. 2005. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8143-2696-1.

- "MS Chi-Cheemaun About Us". Ontario Ferries. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- Stonehouse, Frederick (1985, 1998). Lake Superior's Shipwreck Coast, p. 267, Avery Color Studios, Gwinn, MI ISBN 0-932212-43-3

- Matile, Roger (April 11, 2004) "Has a famed Great Lakes mystery been solved?" Archived January 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Ledger-Sentinel, Oswego, Illinois.

- France claims historic Great Lakes wreck, Randy Boswell, Canwest News Service, February 17, 2009.

- Explorer says Griffin shipwreck may be found, Associated Press, June 24, 2014.

- "Century-old shipwreck discovered". Associated Press. September 10, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- "Divers find 1780 British warship". BBC News. June 14, 2008. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- "L.R. Doty, ship that sank in Lake Michigan 112 years ago, found largely intact near Milwaukee". Star Tribune. Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota. June 24, 2010. Archived from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Bowlus, W. Bruce (2010). Iron Ore Transport on the Great Lakes: The Development of a Delivery System to Feed American Industry. McFarland. p. 227, n.35. ISBN 978-0-7864-8655-7.

- "Federal Statute on Great Lakes. Water Diversions. Water Resources Development Act". Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). dnr.state.oh.us

- "Great Lakes—St" (PDF). Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- Agreement. Great Lakes-St Lawrence River Basin Water Resources. cglg.org. December 13, 2005

- Back to Water Conservation. www.greatlakes.org

- "Great Lakes Restoration Initiative home page". Archived from the original on February 6, 2016.

Further reading

- Peter Annin (2006). The Great Lakes Water Wars. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-61091-077-4.

- Beltran, R. et al. The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book. (United States Environmental Protection Agency and Government of Canada, 1995, ISBN 0-662-23441-3).

- Coon, W.F. and R.A. Sheets. Estimate of Ground Water in Storage in the Great Lakes Basin [Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5180]. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, 2006.

- Egan, Dan (2018). The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-35555-0.

- Helen Hornbeck Tanner (1987). Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2056-0.

- Riley, John L. (2013) The Once and Future Great Lakes Country: An Ecological History (McGill-Queen's University Press 516 pages; traces environmental change in the region since the last ice age.

- Holling, Holling Clancy Paddle to the Sea (ISBN 0-395-15082-5), an illustrated children's book about the Great Lakes and their environment. Beautiful and educational.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Great Lakes. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Lakes. |

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Great Lakes website of the Canadian Department of the Environment

- Great Lakes website of the United States Environmental Protection Agency

- Binational website of USEPA and Environment Canada for Great Lakes Water Quality

- Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory website (an arm of the American National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

- Great Lakes Information Network, sponsored by the Great Lakes Commission, an official American interstate compact agency.

- Great Lakes Echo, a publication covering Great Lakes environmental issues

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes, digital library covering Great Lakes history.

Dynamically updated data