Garnet

Garnets ( /ˈɡɑːrnɪt/) are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

| Garnet | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Nesosilicate |

| Formula (repeating unit) | The general formula X3Y2(SiO4)3 |

| Crystal system | Isometric |

| Crystal class | |

| Space group | Ia3d |

| Identification | |

| Color | virtually all colors, blue is very rare |

| Crystal habit | Rhombic dodecahedron or cubic |

| Cleavage | Indistinct |

| Fracture | conchoidal to uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6.5–7.5 |

| Luster | vitreous to resinous |

| Streak | White |

| Specific gravity | 3.1–4.3 |

| Polish luster | vitreous to subadamantine[1] |

| Optical properties | Single refractive, often anomalous double refractive[1] |

| Refractive index | 1.72–1.94 |

| Birefringence | None |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | variable |

| Other characteristics | variable magnetic attraction |

| Major varieties | |

| Pyrope | Mg3Al2Si3O12 |

| Almandine | Fe3Al2Si3O12 |

| Spessartine | Mn3Al2Si3O12 |

| Andradite | Ca3Fe2Si3O12 |

| Grossular | Ca3Al2Si3O12 |

| Uvarovite | Ca3Cr2Si3O12 |

All species of garnets possess similar physical properties and crystal forms, but differ in chemical composition. The different species are pyrope, almandine, spessartine, grossular (varieties of which are hessonite or cinnamon-stone and tsavorite), uvarovite and andradite. The garnets make up two solid solution series: pyrope-almandine-spessartine and uvarovite-grossular-andradite.

Etymology

The word garnet comes from the 14th‑century Middle English word gernet, meaning 'dark red'. It is derived from the Latin granatus, from granum ('grain, seed'). This is possibly a reference to mela granatum or even pomum granatum ('pomegranate',[2] Punica granatum), a plant whose fruits contain abundant and vivid red seed covers (arils), which are similar in shape, size, and color to some garnet crystals.[3]

Physical properties

Properties

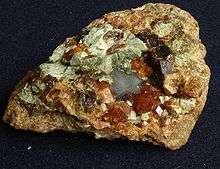

Garnet species are found in many colours including red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, pink, brown, black and colourless, with reddish shades most common.

Garnet species' light transmission properties can range from the gemstone-quality transparent specimens to the opaque varieties used for industrial purposes as abrasives. The mineral's luster is categorized as vitreous (glass-like) or resinous (amber-like).

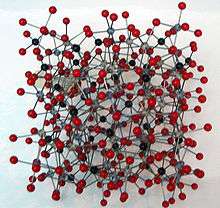

Crystal structure

Garnets are nesosilicates having the general formula X3Y2(SiO

4)3. The X site is usually occupied by divalent cations (Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn)2+ and the Y site by trivalent cations (Al, Fe, Cr)3+ in an octahedral/tetrahedral framework with [SiO4]4− occupying the tetrahedra.[4] Garnets are most often found in the dodecahedral crystal habit, but are also commonly found in the trapezohedron habit. They crystallize in the cubic system, having three axes that are all of equal length and perpendicular to each other. Garnets do not show cleavage, so when they fracture under stress, sharp, irregular (conchoidal) pieces are formed

Hardness

Because the chemical composition of garnet varies, the atomic bonds in some species are stronger than in others. As a result, this mineral group shows a range of hardness on the Mohs scale of about 6.5 to 7.5. The harder species like almandine are often used for abrasive purposes.

Magnetics used in garnet series identification

For gem identification purposes, a pick-up response to a strong neodymium magnet separates garnet from all other natural transparent gemstones commonly used in the jewelry trade. Magnetic susceptibility measurements in conjunction with refractive index can be used to distinguish garnet species and varieties, and determine the composition of garnets in terms of percentages of end-member species within an individual gem.[5]

Garnet group endmember species

Pyralspite garnets – aluminium in Y site

- Almandine: Fe3Al2(SiO4)3

- Pyrope: Mg3Al2(SiO4)3

- Spessartine: Mn3Al2(SiO4)3

Almandine

Almandine, sometimes incorrectly called almandite, is the modern gem known as carbuncle (though originally almost any red gemstone was known by this name). The term "carbuncle" is derived from the Latin meaning "live coal" or burning charcoal. The name Almandine is a corruption of Alabanda, a region in Asia Minor where these stones were cut in ancient times. Chemically, almandine is an iron-aluminium garnet with the formula Fe3Al2(SiO4)3; the deep red transparent stones are often called precious garnet and are used as gemstones (being the most common of the gem garnets). Almandine occurs in metamorphic rocks like mica schists, associated with minerals such as staurolite, kyanite, andalusite, and others. Almandine has nicknames of Oriental garnet, almandine ruby, and carbuncle.

Pyrope

Pyrope (from the Greek pyrōpós meaning "fire-eyed") is red in color and chemically an aluminium silicate with the formula Mg3Al2(SiO4)3, though the magnesium can be replaced in part by calcium and ferrous iron. The color of pyrope varies from deep red to black. Pyrope and spessartine gemstones have been recovered from the Sloan diamondiferous kimberlites in Colorado, from the Bishop Conglomerate and in a Tertiary age lamprophyre at Cedar Mountain in Wyoming.[6]

A variety of pyrope from Macon County, North Carolina is a violet-red shade and has been called rhodolite, Greek for "rose". In chemical composition it may be considered as essentially an isomorphous mixture of pyrope and almandine, in the proportion of two parts pyrope to one part almandine. Pyrope has tradenames some of which are misnomers; Cape ruby, Arizona ruby, California ruby, Rocky Mountain ruby, and Bohemian garnet from the Czech Republic. Another intriguing find is the blue color-changing garnets from Madagascar, a pyrope-spessartine mix. The color of these blue garnets is not like sapphire blue in subdued daylight but more reminiscent of the grayish blues and greenish blues sometimes seen in spinel. However, in white LED light, the color is equal to the best cornflower blue sapphire, or D block tanzanite; this is due to the blue garnet's ability to absorb the yellow component of the emitted light.

Pyrope is an indicator mineral for high-pressure rocks. The garnets from mantle-derived rocks, peridotites, and eclogites commonly contain a pyrope variety.

Spessartine

Spessartine or spessartite is manganese aluminium garnet, Mn3Al2(SiO4)3. Its name is derived from Spessart in Bavaria. It occurs most often in granite pegmatite and allied rock types and in certain low grade metamorphic phyllites. Spessartine of an orange-yellow is found in Madagascar. Violet-red spessartines are found in rhyolites in Colorado and Maine.

Pyrope–spessartine (blue garnet or color-change garnet)

Blue pyrope–spessartine garnets were discovered in the late 1990s in Bekily, Madagascar. This type has also been found in parts of the United States, Russia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Turkey. It changes color from blue-green to purple depending on the color temperature of viewing light, as a result of the relatively high amounts of vanadium (about 1 wt.% V2O3).[7]

Other varieties of color-changing garnets exist. In daylight, their color ranges from shades of green, beige, brown, gray, and blue, but in incandescent light, they appear a reddish or purplish/pink color.

This is the rarest type of garnet. Because of its color-changing quality, this kind of garnet resembles Alexandrite.

Ugrandite group – calcium in X site

- Andradite: Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3

- Grossular: Ca3Al2(SiO4)3

- Uvarovite: Ca3Cr2(SiO4)3

Andradite

Andradite is a calcium-iron garnet, Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3, is of variable composition and may be red, yellow, brown, green or black. The recognized varieties are topazolite (yellow or green), demantoid (green) and melanite (black). Andradite is found both in deep-seated igneous rocks like syenite as well as serpentines, schists, and crystalline limestone. Demantoid has been called the "emerald of the Urals" from its occurrence there, and is one of the most prized of garnet varieties. Topazolite is a golden-yellow variety and melanite is a black variety.

Grossular

Grossular is a calcium-aluminium garnet with the formula Ca3Al2(SiO4)3, though the calcium may in part be replaced by ferrous iron and the aluminium by ferric iron. The name grossular is derived from the botanical name for the gooseberry, grossularia, in reference to the green garnet of this composition that is found in Siberia. Other shades include cinnamon brown (cinnamon stone variety), red, and yellow. Because of its inferior hardness to zircon, which the yellow crystals resemble, they have also been called hessonite from the Greek meaning inferior. Grossular is found in contact metamorphosed limestones with vesuvianite, diopside, wollastonite and wernerite.

Grossular garnet from Kenya and Tanzania has been called tsavorite. Tsavorite was first described in the 1960s in the Tsavo area of Kenya, from which the gem takes its name.[8]

Uvarovite

Uvarovite is a calcium chromium garnet with the formula Ca3Cr2(SiO4)3. This is a rather rare garnet, bright green in color, usually found as small crystals associated with chromite in peridotite, serpentinite, and kimberlites. It is found in crystalline marbles and schists in the Ural mountains of Russia and Outokumpu, Finland.

Less common species

- Calcium in X site

- Hydroxide bearing – calcium in X site

- Hydrogrossular: Ca3Al2(SiO4)3−x(OH)4x

- Hibschite: Ca3Al2(SiO4)3−x(OH)4x (where x is between 0.2 and 1.5)

- Katoite: Ca3Al2(SiO4)3−x(OH)4x (where x is greater than 1.5)

- Hydrogrossular: Ca3Al2(SiO4)3−x(OH)4x

- Magnesium or manganese in X site

- Knorringite: Mg3Cr2(SiO4)3

- Majorite: Mg3(Fe2+Si)(SiO4)3

- Calderite: Mn3Fe3+2(SiO4)3

Knorringite

Knorringite is a magnesium-chromium garnet species with the formula Mg3Cr2(SiO4)3. Pure endmember knorringite never occurs in nature. Pyrope rich in the knorringite component is only formed under high pressure and is often found in kimberlites. It is used as an indicator mineral in the search for diamonds.

Garnet structural group

- Formula: X3Z2(TO4)3 (X = Ca, Fe, etc., Z = Al, Cr, etc., T = Si, As, V, Fe, Al)

- All are cubic or strongly pseudocubic.

| IMA/CNMNC Nickel-Strunz Mineral class | Mineral name | Formula | Crystal system | Point group | Space group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 04 Oxide | Bitikleite-(SnAl) | Ca3SnSb(AlO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| 04 Oxide | Bitikleite-(SnFe) | Ca3(SnSb5+)(Fe3+O)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| 04 Oxide | Bitikleite-(ZrFe) | Ca3SbZr(Fe3+O4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| 04 Tellurate | Yafsoanite | Ca3Zn3(Te6+O6)2 | isometric | m3m or 432 | Ia3d or I4132 |

| 08 Arsenate | Berzeliite | NaCa2Mg2(AsO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| 08 Vanadate | Palenzonaite | NaCa2Mn2+2(VO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| 08 Vanadate | Schäferite | NaCa2Mg2(VO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

- IMA/CNMNC – Nickel-Strunz – Mineral subclass: 09.A Nesosilicate

- Nickel-Strunz classification: 09.AD.25

| Mineral name | Formula | Crystal system | Point group | Space group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almandine | Fe2+3Al2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Andradite | Ca3Fe3+2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Calderite | Mn+23Fe+32(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Goldmanite | Ca3V3+2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Grossular | Ca3Al2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Henritermierite | Ca3Mn3+2(SiO4)2(OH)4 | tetragonal | 4/mmm | I41/acd |

| Hibschite | Ca3Al2(SiO4)(3-x)(OH)4x (x= 0.2–1.5) | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Katoite | Ca3Al2(SiO4)(3-x)(OH)4x (x= 1.5-3) | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Kerimasite | Ca3Zr2(Fe+3O4)2(SiO4) | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Kimzeyite | Ca3Zr2(Al+3O4)2(SiO4) | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Knorringite | Mg3Cr2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Majorite | Mg3(Fe2+Si)(SiO4)3 | tetragonal | 4/m or 4/mmm | I41/a or I41/acd |

| Menzerite-(Y) | Y2CaMg2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Momoiite | Mn2+3V3+2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Morimotoite | Ca3(Fe2+Ti4+)(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Pyrope | Mg3Al2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Schorlomite | Ca3Ti4+2(Fe3+O4)2(SiO4) | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Spessartine | Mn2+3Al2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Toturite | Ca3Sn2(Fe3+O4)2(SiO4) | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

| Uvarovite | Ca3Cr2(SiO4)3 | isometric | m3m | Ia3d |

- References: Mindat.org; mineral name, chemical formula and space group (American Mineralogist Crystal Structure Database) of the IMA Database of Mineral Properties/ RRUFF Project, Univ. of Arizona, was preferred most of the time. Minor components in formulae have been left out to highlight the dominant chemical endmember that defines each species.

Synthetic garnets

The crystallographic structure of garnets has been expanded from the prototype to include chemicals with the general formula A3B2(C O4)3. Besides silicon, a large number of elements have been put on the C site, including Ge, Ga, Al, V and Fe.[9]

Yttrium aluminium garnet (YAG), Y3Al2(AlO4)3, is used for synthetic gemstones. Due to its fairly high refractive index, YAG was used as a diamond simulant in the 1970s until the methods of producing the more advanced simulant cubic zirconia in commercial quantities were developed. When doped with neodymium (Nd3+), these YAl-garnets may be used as the lasing medium in lasers.

Interesting magnetic properties arise when the appropriate elements are used. In yttrium iron garnet (YIG), Y3Fe2(FeO4)3, the five iron(III) ions occupy two octahedral and three tetrahedral sites, with the yttrium(III) ions coordinated by eight oxygen ions in an irregular cube. The iron ions in the two coordination sites exhibit different spins, resulting in magnetic behavior. YIG is a ferrimagnetic material having a Curie temperature of 550 K.

Another example is gadolinium gallium garnet, Gd3Ga2(GaO4)3 which is synthesized for use as a substrate for liquid-phase epitaxy of magnetic garnet films for bubble memory and magneto-optical applications.

Geological importance

The Garnet group is a key mineral in interpreting the genesis of many igneous and metamorphic rocks via geothermobarometry. Diffusion of elements is relatively slow in garnet compared to rates in many other minerals, and garnets are also relatively resistant to alteration. Hence, individual garnets commonly preserve compositional zonations that are used to interpret the temperature-time histories of the rocks in which they grew. Garnet grains that lack compositional zonation commonly are interpreted as having been homogenized by diffusion, and the inferred homogenization also has implications for the temperature-time history of the host rock.

Garnets are also useful in defining metamorphic facies of rocks. For instance, eclogite can be defined as a rock of basalt composition, but mainly consisting of garnet and omphacite. Pyrope-rich garnet is restricted to relatively high-pressure metamorphic rocks, such as those in the lower crust and in the Earth's mantle. Peridotite may contain plagioclase, or aluminium-rich spinel, or pyrope-rich garnet, and the presence of each of the three minerals defines a pressure-temperature range in which the mineral could equilibrate with olivine plus pyroxene: the three are listed in order of increasing pressure for stability of the peridotite mineral assemblage. Hence, garnet peridotite must have been formed at great depth in the earth. Xenoliths of garnet peridotite have been carried up from depths of 100 km (62 mi) and greater by kimberlite, and garnets from such disaggegated xenoliths are used as a kimberlite indicator minerals in diamond prospecting. At depths of about 300 to 400 km (190 to 250 mi) and greater, a pyroxene component is dissolved in garnet, by the substitution of (Mg,Fe) plus Si for 2Al in the octahedral (Y) site in the garnet structure, creating unusually silica-rich garnets that have solid solution towards majorite. Such silica-rich garnets have been identified as inclusions within diamonds.

Uses

Gemstones

Red garnets were the most commonly used gemstones in the Late Antique Roman world, and the Migration Period art of the "barbarian" peoples who took over the territory of the Western Roman Empire. They were especially used inlaid in gold cells in the cloisonné technique, a style often just called garnet cloisonné, found from Anglo-Saxon England, as at Sutton Hoo, to the Black Sea. Thousands of Tamraparniyan gold, silver and red garnet shipments were made in the old world, including to Rome, Greece, the Middle East, Serica and Anglo Saxons; recent findings such as the Staffordshire Hoard and the pendant of the Winfarthing Woman skeleton of Norfolk confirm an established gem trade route with South India and Tamraparni (ancient Sri Lanka), known from antiquity for its production of gemstones.[10][11][12]

Pure crystals of garnet are still used as gemstones. The gemstone varieties occur in shades of green, red, yellow, and orange.[13] In the US it is known as the birthstone for January.[1] It is the state mineral of Connecticut,[14] New York's gemstone,[15] and star garnet (garnet with rutile asterisms) is the state gemstone of Idaho.[16]

Industrial uses

Garnet sand is a good abrasive, and a common replacement for silica sand in sand blasting. Alluvial garnet grains which are rounder are more suitable for such blasting treatments. Mixed with very high pressure water, garnet is used to cut steel and other materials in water jets. For water jet cutting, garnet extracted from hard rock is suitable since it is more angular in form, therefore more efficient in cutting.

Garnet paper is favored by cabinetmakers for finishing bare wood.[17]

Garnet sand is also used for water filtration media.

As an abrasive, garnet can be broadly divided into two categories; blasting grade and water jet grade. The garnet, as it is mined and collected, is crushed to finer grains; all pieces which are larger than 60 mesh (250 micrometers) are normally used for sand blasting. The pieces between 60 mesh (250 micrometers) and 200 mesh (74 micrometers) are normally used for water jet cutting. The remaining garnet pieces that are finer than 200 mesh (74 micrometers) are used for glass polishing and lapping. Regardless of the application, the larger grain sizes are used for faster work and the smaller ones are used for finer finishes.

There are different kinds of abrasive garnets which can be divided based on their origin. The largest source of abrasive garnet today is garnet-rich beach sand which is quite abundant on Indian and Australian coasts and the main producers today are Australia and India.[18]

This material is particularly popular due to its consistent supplies, huge quantities and clean material. The common problems with this material are the presence of ilmenite and chloride compounds. Since the material has been naturally crushed and ground on the beaches for past centuries, the material is normally available in fine sizes only. Most of the garnet at the Tuticorin beach in south India is 80 mesh, and ranges from 56 mesh to 100 mesh size.

River garnet is particularly abundant in Australia. The river sand garnet occurs as a placer deposit.[19]

Rock garnet is perhaps the garnet type used for the longest period of time. This type of garnet is produced in America, China and western India. These crystals are crushed in mills and then purified by wind blowing, magnetic separation, sieving and, if required, washing. Being freshly crushed, this garnet has the sharpest edges and therefore performs far better than other kinds of garnet. Both the river and the beach garnet suffer from the tumbling effect of hundreds of thousands of years which rounds off the edges.

Cultural significance

Garnet is the birthstone of January.[20][21] It is also the birthstone of Aquarius in tropical astrology.[22][23]

See also

- Tsavorite

- Mineral collecting

- Abrasive blasting

References

- Gemological Institute of America, GIA Gem Reference Guide 1995, ISBN 0-87311-019-6

- pomegranate. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved on 2011-12-25.

- garnet. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved on 2011-12-25.

- Smyth, Joe. "Mineral Structure Data". Garnet. University of Colorado. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- D. B. Hoover, B. Williams, C. Williams and C. Mitchell, Magnetic susceptibility, a better approach to defining garnets, The Journal of Gemmology, 2008, Volume 31, No. 3/4 pp. 91–103

- Hausel, W. Dan (2000). Gemstones and Other Unique Rocks and Minerals of Wyoming – Field Guide for Collectors. Laramie, Wyoming: Wyoming Geological Survey. pp. 268 p.

- "Garnets from Madagascar with a Color Change of Blue-Green to Purple". Gems and Gemology. Gemological Institute of America Inc. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

- Mindat.org - Tsavorite

- S. Geller Crystal chemistry of the garnets Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, 125(125), pp. 1–47 (1967) doi:10.1524/zkri.1967.125.125.1

- "Staffordshire Hoard Festival 2019". The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "A trail of garnet and gold: Sri Lanka to Anglo-Saxon England". The Historical Association. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "Acquisitions of the month: June 2018". Apollo Magazine. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Geological Sciences at University of Texas, Austin. Geo.utexas.edu. Retrieved on 2011-12-25.

- State of Connecticut, Sites º Seals º Symbols Archived 2008-07-31 at the Wayback Machine; Connecticut State Register & Manual; retrieved on December 20, 2008

- New York State Gem Archived 2007-12-08 at the Wayback Machine; State Symbols USA; retrieved on October 12, 2007

- Idaho state symbols. idaho.gov

- Joyce, Ernest (1987) [1970]. Peters, Alan (ed.). The Technique of Furniture Making (4th ed.). London: Batsford. ISBN 071344407X.

- Briggs, J. (2007). The Abrasives Industry in Europe and North America. Materials Technology Publications. ISBN 1-871677-52-1.

- Industrial Mineral Opportunities in New South Wales

- "Tips & Tools: Birthstones". The National Association of Goldsmiths. Archived from the original on 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- Kunz, George F. (1913). The curious lore of precious stones. Lippincott. pp. 275–306, pp. 319-320

- Knuth, Bruce G. (2007). Gems in Myth, Legend and Lore (Revised edition). Parachute: Jewelers Press. p. 294.

- Kunz (1913), pp. 345–347

- "New York State Information". State of New York. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "State of Connecticut – Sites, Seals and Symbols". State of Connecticut. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Idaho Symbols". State of Idaho. Archived from the original on 2010-06-30. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Vermont Emblems". State of Vermont. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- http://www.gemstonemagnetism.com contains a comprehensive section about garnets and garnet magnetism.

- USGS Garnet locations – USA

- http://gemstone.org/education/gem-by-gem/154-garnet

- http://www.mindat.org/min-10272.html

- Blog post on garnets on the Law Library of Congress's blog