Ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally elephants') and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is the same, regardless of the species of origin. The trade in certain teeth and tusks other than elephant is well established and widespread; therefore, "ivory" can correctly be used to describe any mammalian teeth or tusks of commercial interest which are large enough to be carved or scrimshawed.[1]

Ivory has been valued since ancient times in art or manufacturing for making a range of items from ivory carvings to false teeth, piano keys, fans, dominoes[2] and joint tubes.[3] Elephant ivory is the most important source, but ivory from mammoth, walrus, hippopotamus, sperm whale, killer whale, narwhal and warthog are used as well.[4][5] Elk also have two ivory teeth, which are believed to be the remnants of tusks from their ancestors.[6]

The national and international trade in ivory of threatened species such as African and Asian elephants is illegal.[7] The word ivory ultimately derives from the ancient Egyptian âb, âbu ("elephant"), through the Latin ebor- or ebur.[8]

Uses

Both the Greek and Roman civilizations practiced ivory carving to make large quantities of high value works of art, precious religious objects, and decorative boxes for costly objects. Ivory was often used to form the white of the eyes of statues.

There is some evidence of either whale or walrus ivory used by the ancient Irish. Solinus, a Roman writer in the 3rd century claimed that the Celtic peoples in Ireland would decorate their sword-hilts with the 'teeth of beasts that swim in the sea'. Adomnan of Iona wrote a story about St Columba giving a sword decorated with carved ivory as a gift that a penitent would bring to his master so he could redeem himself from slavery.[9]

The Syrian and North African elephant populations were reduced to extinction, probably due to the demand for ivory in the Classical world.[10]

The Chinese have long valued ivory for both art and utilitarian objects. Early reference to the Chinese export of ivory is recorded after the Chinese explorer Zhang Qian ventured to the west to form alliances to enable the eventual free movement of Chinese goods to the west; as early as the first century BC, ivory was moved along the Northern Silk Road for consumption by western nations.[11] Southeast Asian kingdoms included tusks of the Indian elephant in their annual tribute caravans to China. Chinese craftsmen carved ivory to make everything from images of deities to the pipe stems and end pieces of opium pipes.[12]

The Buddhist cultures of Southeast Asia, including Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, traditionally harvested ivory from their domesticated elephants. Ivory was prized for containers due to its ability to keep an airtight seal. It was also commonly carved into elaborate seals utilized by officials to "sign" documents and decrees by stamping them with their unique official seal.[13]

In Southeast Asian countries, where Muslim Malay peoples live, such as Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines, ivory was the material of choice for making the handles of kris daggers. In the Philippines, ivory was also used to craft the faces and hands of Catholic icons and images of saints prevalent in the Santero culture.

Tooth and tusk ivory can be carved into a vast variety of shapes and objects. Examples of modern carved ivory objects are okimono, netsukes, jewelry, flatware handles, furniture inlays, and piano keys. Additionally, warthog tusks, and teeth from sperm whales, orcas and hippos can also be scrimshawed or superficially carved, thus retaining their morphologically recognizable shapes.

Ivory usage in the last thirty years has moved towards mass production of souvenirs and jewelry. In Japan, the increase in wealth sparked consumption of solid ivory hanko – name seals – which before this time had been made of wood. These hanko can be carved out in a matter of seconds using machinery and were partly responsible for massive African elephant decline in the 1980s, when the African elephant population went from 1.3 million to around 600,000 in ten years.[14][15]

Consumption before plastics

Prior to the introduction of plastics, ivory had many ornamental and practical uses, mainly because of the white color it presents when processed. It was formerly used to make cutlery handles, billiard balls, piano keys, Scottish bagpipes, buttons and a wide range of ornamental items.

Synthetic substitutes for ivory in the use of most of these items have been developed since 1800: the billiard industry challenged inventors to come up with an alternative material that could be manufactured;[16]:17 the piano industry abandoned ivory as a key covering material in the 1970s.

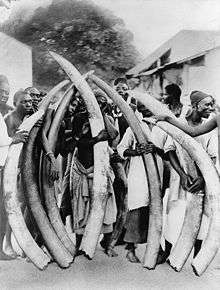

Ivory can be taken from dead animals – however, most ivory came from elephants that were killed for their tusks. For example, in 1930 to acquire 40 tons of ivory required the killing of approximately 700 elephants.[17] Other animals which are now endangered were also preyed upon, for example, hippos, which have very hard white ivory prized for making artificial teeth.[18] In the first half of the 20th century, Kenyan elephant herds were devastated because of demand for ivory, to be used for piano keys.[19]

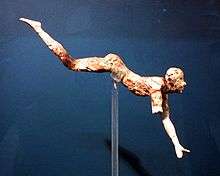

During the Art Deco era from 1912 to 1940, dozens (if not hundreds) of European artists used ivory in the production of chryselephantine statues. Two of the most frequent users of ivory in their sculptured artworks were Ferdinand Preiss and Claire Colinet.[20]

Availability

Owing to the rapid decline in the populations of the animals that produce it, the importation and sale of ivory in many countries is banned or severely restricted. In the ten years preceding a decision in 1989 by CITES to ban international trade in African elephant ivory, the population of African elephants declined from 1.3 million to around 600,000. It was found by investigators from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) that CITES sales of stockpiles from Singapore and Burundi (270 tonnes and 89.5 tonnes respectively) had created a system that increased the value of ivory on the international market, thus rewarding international smugglers and giving them the ability to control the trade and continue smuggling new ivory.[14][15]

Since the ivory ban, some Southern African countries have claimed their elephant populations are stable or increasing, and argued that ivory sales would support their conservation efforts. Other African countries oppose this position, stating that renewed ivory trading puts their own elephant populations under greater threat from poachers reacting to demand. CITES allowed the sale of 49 tonnes of ivory from Zimbabwe, Namibia and Botswana in 1997 to Japan.[21][22]

In 2007, under pressure from the International Fund for Animal Welfare, eBay banned all international sales of elephant-ivory products. The decision came after several mass slaughters of African elephants, most notably the 2006 Zakouma elephant slaughter in Chad. The IFAW found that up to 90% of the elephant-ivory transactions on eBay violated their own wildlife policies and could potentially be illegal. In October 2008, eBay expanded the ban, disallowing any sales of ivory on eBay.

A more recent sale in 2008 of 108 tonnes from the three countries and South Africa took place to Japan and China.[23][24] The inclusion of China as an "approved" importing country created enormous controversy, despite being supported by CITES, the World Wide Fund for Nature and Traffic.[25] They argued that China had controls in place and the sale might depress prices. However, the price of ivory in China has skyrocketed.[26] Some believe this may be due to deliberate price fixing by those who bought the stockpile, echoing the warnings from the Japan Wildlife Conservation Society on price-fixing after sales to Japan in 1997,[27] and monopoly given to traders who bought stockpiles from Burundi and Singapore in the 1980s.

A 2019 peer-reviewed study reported that the rate of African elephant poaching was in decline, with the annual poaching mortality rate peaking at over 10% in 2011 and falling to below 4% by 2017.[28] The study found that the "annual poaching rates in 53 sites strongly correlate with proxies of ivory demand in the main Chinese markets, whereas between-country and between-site variation is strongly associated with indicators of corruption and poverty."[28] Based on these findings, the study authors recommended action to both reduce demand for ivory in China and other main markets and to decrease corruption and poverty in Africa.[28]

In 2006, 19 African countries signed the "Accra Declaration" calling for a total ivory trade ban, and 20 range states attended a meeting in Kenya calling for a 20-year moratorium in 2007.[29]

Controversy and conservation issues

The use and trade of elephant ivory have become controversial because they have contributed to seriously declining elephant populations in many countries. It is estimated that consumption in Great Britain alone in 1831 amounted to the deaths of nearly 4,000 elephants. In 1975, the Asian elephant was placed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which prevents international trade between member states of species that are threatened by trade. The African elephant was placed on Appendix I in January 1990. Since then, some southern African countries have had their populations of elephants "downlisted" to Appendix II, allowing the domestic trade of non-ivory items; there have also been two "one off" sales of ivory stockpiles.[14][30][31][32][33]

In June 2015, more than a ton of confiscated ivory was crushed in New York's Times Square by the Wildlife Conservation Society to send a message that the illegal trade will not be tolerated. The ivory, confiscated in New York and Philadelphia, was sent up a conveyor belt into a rock crusher. The Wildlife Conservation Society has pointed out that the global ivory trade leads to the slaughter of up to 35,000 elephants a year in Africa. In June 2018, Conservative MEPs’ Deputy Leader Jacqueline Foster MEP urged the EU to follow the UK's lead and introduce a tougher ivory ban across Europe.[34]

China was the biggest market for poached ivory but announced they would phase out the legal domestic manufacture and sale of ivory products in May 2015. In September of the same year, China and the U.S. announced they would "enact a nearly complete ban on the import and export of ivory."[35] The Chinese market has a high degree of influence on the elephant population.[36][37]

Alternative sources

Trade in the ivory from the tusks of dead woolly mammoths frozen in the tundra has occurred for 300 years and continues to be legal. Mammoth ivory is used today to make handcrafted knives and similar implements. Mammoth ivory is rare and costly because mammoths have been extinct for millennia, and scientists are hesitant to sell museum-worthy specimens in pieces.[38] Some estimates suggest that 10 million mammoths are still buried in Siberia.[39]

A species of hard nut is gaining popularity as a replacement for ivory, although its size limits its usability. It is sometimes called vegetable ivory, or tagua, and is the seed endosperm of the ivory nut palm commonly found in coastal rainforests of Ecuador, Peru and Colombia.[40]

Fossil walrus ivory from animals that died before 1972 is legal to buy and sell or possess in the United States, unlike many other types of ivory.[41]

Gallery

Ancient Greek ivory pyxis with griffins attacking stags. Late 15th century BC

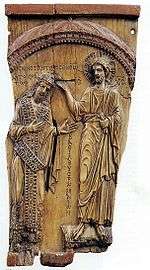

Ancient Greek ivory pyxis with griffins attacking stags. Late 15th century BC A piece of carved ivory from the Pushkin Museum representing Christ blessing Emperor Constantine VII. Mid 10th century AD

A piece of carved ivory from the Pushkin Museum representing Christ blessing Emperor Constantine VII. Mid 10th century AD Ivory cover of the Codex Aureus of Lorsch, c. 810, Carolingian dynasty, Victoria and Albert Museum

Ivory cover of the Codex Aureus of Lorsch, c. 810, Carolingian dynasty, Victoria and Albert Museum Pig tusks

Pig tusks Battle of Hannibal and Scipio (Alexander's victory over Poros), by Ignaz Elhafen, ca. 1700, Warsaw Royal Castle

Battle of Hannibal and Scipio (Alexander's victory over Poros), by Ignaz Elhafen, ca. 1700, Warsaw Royal Castle Section through the ivory tusk of a mammoth

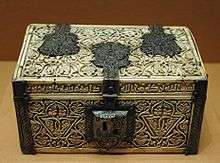

Section through the ivory tusk of a mammoth Casket, ivory and silver, Caliphate of Córdoba, 966

Casket, ivory and silver, Caliphate of Córdoba, 966 The Morgan Casket, an 11th-century ivory casket attributed to Southern Italy, currently in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Morgan Casket, an 11th-century ivory casket attributed to Southern Italy, currently in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art A cubical ivory bead or game piece from the collections of the Hunt Museum

A cubical ivory bead or game piece from the collections of the Hunt Museum

See also

- Destruction of ivory

- Ivory carving

- Ivory tower

- Vegetable ivory

- Walrus ivory

- Jim Nyamu

References

- "Identification Guide for Ivory and Ivory Substitutes" (PDF). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- "George Washington's false teeth not wooden". Associated Press. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- "Joint Tubes". Google Image Search.

- Espinoza, E. O.; M. J. Mann (1991). Identification guide for ivory and ivory substitutes. Baltimore: World Wildlife Fund and Conservation Foundation.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Forensics Lab. "Ivory Identification Guide – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Forensics Laboratory". fws.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- "Elk Facts". coloradoelkbreeders.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Singh, R. R., Goyal, S. P., Khanna, P. P., Mukherjee, P. K., & Sukumar, R. (2006). Using morphometric and analytical techniques to characterize elephant ivory. Forensic Science International 162 (1): 144–151.

- The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford 1993), entry for "ivory."

- Adomnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Penguin books, 1995

- Revello, Manuela, “Orientalising ivories from Italy”, in BAR, British Archaeological Reports, Proceedings of International Symposium of Mediterranean Archaeology, February 24–26, 2005, Università degli Studi di Chieti, 111–118.

- Hogan, C. M. (2007). "Silk Road, North China". Megalithic.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Martin, S. (2007). The Art of Opium Antiques. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai

- Daniel Stiles. "Ivory Carving in Thailand". Asianart.com. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- "To Save An Elephant" by Allan Thornton & Dave Currey, Doubleday 1991 ISBN 0-385-40111-6

- EIA (1989). "A System of Extinction – the African Elephant Disaster". Environmental Investigation Agency, London.

- Shamos, Mike (1999). The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 1-55821-797-5.

- "Ivory Tusks by the Ton". Popular Science: 45. November 1930.

- Tomlinson, C., ed. (1866). Tomlinson's Cyclopaedia of Useful Arts. London: Virtue & Co.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) Vol I, pages 929–930.

- "Piano Keys From Elephant Tusk". Popular Science. January 1937.

- Catley, Bryan (1978). Art Deco and Other Figures (1st ed.). Woodbridge, England: Antique Collectors' Club Ltd. pp. 112–123. ISBN 978-1-85149-382-1.

- "HSI Ivory trade timeline" (PDF). Hsi.org. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- "Living Proof", Dave Currey & Helen Moore, A report by Environmental Investigation Agency Sept 1994

- "Campaigners fear for elephants and their own credibility". The Economist. July 2008.

- CITES summary record of Standing Committee 57 2008

- "Ivory sales". Traffic. 2008-10-28. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Strazjuso, Jason; Caesy, Michael; Foreman, William (2010-05-15). "Ivory Trade threatens African Elephant". NBC News. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- "Elephant poaching? None of our business' Influence of Japanese ivory market on illegal transboundary ivory trade" (PDF). Japan Tiger and Elephant Fund (JTEF). March 2010.

- Severin Hauenstein, Mrigesh Kshatriya, Julian Blanc, Carsten F. Dormann & Colin M. Beale, African elephant poaching rates correlate with local poverty, national corruption and global ivory price, Nature Communications, vol. 10, 2242 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09993-2.

- "African countries set to lock horns over ivory". Bt.com.bn. 2007-05-31. Archived from the original on 2016-08-21. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- "Asian Elephant". Cites.org. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- Kaufman, Marc (2007-02-27). "Increased Demand for Ivory Threatens Elephant Survival". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- "Lifting the Ivory Ban Called Premature". NPR. 2002-10-31. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- "WWF Wildlife Trade – elephant ivory FAQs". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Jacqueline Foster, Emma McClarkin, John Flack (18 July 2018). "Foster, McClarkin, Flack: "4 things we've done to improve animal welfare"". Conservatives in the European Parliament.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ryan, F. (26 September 2015). "China and US agree on ivory ban in bid to end illegal trade globally". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "事实上,大象已经濒临灭绝" [Elephants on the Path of Extinction: The facts]. TheGuardian.com (in Chinese). 8 September 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Isabel Hilton (9 September 2016). "Why the Guardian is publishing its elephant reporting in Chinese". TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Kramer, Andrew E. (2008-03-25). "Trade in mammoth ivory, helped by global thaw, flourishes in Russia". New York Times. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Lister, Adrian; Bahn, Paul G. (2007). Mammoths: giants of the ice age. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25319-3.

- Lara Farrar (2005-04-26). "Could plant ivory save elephants?". CNN. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- Walrus ivory dos and don'ts (PDF) (pamphlet), US Fish and Wildlife Service

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ivory. |