Peridot

Peridot (/ˈpɛrɪdɒt/ or /ˈpɛrɪdoʊ/) (sometimes called chrysolite) is gem-quality olivine and a silicate mineral with the formula of (Mg, Fe)2SiO4. As peridot is a magnesium-rich variety of olivine (forsterite), the formula approaches Mg2SiO4. Its green color is dependent on the iron contents within the structure of the gem. Peridot occurs in silica-deficient rocks such a volcanic basalt as well as in pallasitic meteorites. Peridot is one of only two gems observed to be formed not in the Earth’s crust, but in molten rock of the upper mantle. Gem-quality peridot is rare to find on Earths surface due to its susceptibility to weathering during transportation from deep within the mantle to the surface.

| Peridot | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Silicate mineral variety |

| Formula (repeating unit) | (Mg, Fe)2SiO4 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic |

| Identification | |

| Color | Yellow, to yellow-green, olive-green, to brownish, sometimes a lime-green, to emerald-ish hue |

| Cleavage | Poor |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6.5–7 |

| Luster | vitreous (glassy) |

| Streak | None |

| Specific gravity | 3.2–4.3 |

| Refractive index | 1.64–1.70 |

| Birefringence | +0.036 |

| Pleochroism | Weak |

| Melting point | Very high |

In the Middle Ages, the gemstone was considered a stone that could provide healing powers, curing depression and opening the heart. Peridot is the birthstone for the month of August and the 16 year wedding anniversary gemstone.

Etymology

The origin of the name peridot is uncertain. The Oxford English Dictionary suggests an alteration of Anglo–Norman pedoretés (classical Latin pæderot-), a kind of opal, rather than the Arabic word faridat, meaning "gem".

The Middle English Dictionary's entry on peridot includes several variations: peridod, peritot, pelidod and pilidod — other variants substitute y for the is seen here.[1]

The earliest use in England is in the register of the St Albans Abbey, in Latin, and its translation in 1705 is possibly the first use of peridot in English. It records that on his death in 1245, Bishop John bequeathed various items, including peridot, to the Abbey.[2]

Appearance

Peridot is one of the few gemstones that occur in only one color: an olive-green. The intensity and tint of the green, however, depends on the percentage of iron in the crystal structure, so the color of individual peridot gems can vary from yellow, to olive, to brownish-green. In rare cases, peridot may have a medium-dark toned, pure green with no secondary yellow hue or brown mask.[3]

Mineral Properties

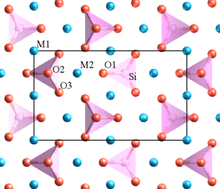

Crystal structure

The molecular structure of peridot consist of isomorphic olivine, silicate, magnesium and iron in an orthorhombic crystal system. In an alternative view, the atomic structure can be described as a hexagonal, close-packed array of oxygen ions with half of the octahedral sites occupied with magnesium or iron ions and one-eighth of the tetrahedral sites occupied by silicon ions.

Surface property

Oxidation of peridot does not occur at natural surface temperature and pressure, but begins to occur slowly at 600°C with rates increasing with temperature.[4] The oxidation of the olivine occurs by initial breakdown of the fayalite component, and subsequent reaction with the forsterite component, to give magnetite and orthopyroxene.

Occurrence

Geologically

Olivine, of which peridot is a type, is a common mineral in mafic and ultramafic rocks, often found in lava and in peridotite xenoliths of the mantle, which lava carries to the surface; however, gem-quality peridot occurs in only a fraction of these settings. Peridots can also be found in meteorites.

Peridots can be differentiated by size and composition. A peridot formed as a result of volcanic activity tends to contain higher concentrations of lithium, nickel and zinc than those found in meteorites.[5]

Olivine is an abundant mineral, but gem-quality peridot is rather rare due to its chemical instability on Earth's surface. Olivine is usually found as small grains and tends to exist in a heavily weathered state, unsuitable for decorative use. Large crystals of forsterite, the variety most often used to cut peridot gems, are rare; as a result olivine is considered to be precious.

In the ancient world, mining of peridot, called topazios then, on St. John's Island in the Red Sea began about 300 B.C.[6]

The principal source of peridot olivine today is the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona.[7] It is also mined at another location in Arizona, and in Arkansas, Hawaii, Nevada, and New Mexico at Kilbourne Hole, in the US; and in Australia, Brazil, China, Egypt, Kenya, Mexico, Myanmar (Burma), Norway, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania.

In meteorites

Peridot crystals have been collected from some pallasite meteorites. These gems are given the name Moldavite to differentiate their origin. The most commonly studied pallasitic peridot belongs to the Indonesian Jeppara meteorite, but others exist such as the Brenham, Esquel, Fukang, and Imilac meteorites.[8]

Gemology

Refractive index readings of faceted gems contain indices α = 1.653, β = 1.670, and γ = 1.689 with a corresponding bi-axial birefringence of 0.036. Study of Chinese peridot gem samples determined the specific gravity hydro-statically to be 3.36. The visible-light spectroscopy of the same Chinese peridot samples showed light bands between 493.0 and 481.0 nm, the strongest absorption at 492.0 nm.[9]

Inclusions are common in peridot crystals but the variety depend on the location it is found at. Stones from Pakistan contain silk and rod like inclusions as well as black chromite crystal inclusions surrounded bi-circular cleavage discs resembling lily pads, and finger print inclusions. Brown Mica flakes are more evident in Arizona gems.[9]

The largest cut peridot olivine is a 310 carat (62 g) specimen in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.

Cultural History

Peridot has been prized since the earliest civilizations for its protective powers to drive away fears and nightmares. It's believed to carry the gift of inner radiance, sharpening the mind and opening it to new levels of awareness and growth, helping one to recognize and realize one’s destiny and spiritual purpose.

Ancient Egyptians believed that Peridot was sent to Earth by the explosion of a star and carried its healing powers. Peridot is the national gem of Egypt known to locals as the Gem of the Sun.

Peridot is sometimes mistaken for emeralds and other green gems. Notable gemologist George Frederick Kunz discussed the confusion between emeralds and peridot in many church treasures, notably the "Three Magi" treasure in the Dom of Cologne, Germany.

Peridot olivine is the birthstone for the month of August and the 16th wedding anniversary gemstone.

Gallery

Peridot from the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona.

Peridot from the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona.- Olive green peridot

- Peridot with milky inclusions

References

- Sherman M Kuhn (1982). Middle English Dictionary. University of Michigan Press. pp. 818–. ISBN 0-472-01163-4.

- Sir James Ware (1705). The Antiquities and History of Ireland. A. Crook. pp. 628–.

- Wise, Richard W. (2016). Secrets Of The Gem Trade, The Connoisseur's Guide To Precious Gemstones (2nd ed.). Lenox, Massachusetts: Brunswick House Press. p. 220. ISBN 9780972822329.

- Knafelc, Joseph; Filiberto, Justin; Ferré, Eric C.; Conder, James A.; Costello, Lacey; Crandall, Jake R.; Dyar, M. Darby; Friedman, Sarah A.; Hummer, Daniel R.; Schwenzer, Susanne P. (2019-05-01). "The effect of oxidation on the mineralogy and magnetic properties of olivine". American Mineralogist. 104 (5): 694–702. doi:10.2138/am-2019-6829. ISSN 0003-004X.

- Shen, A., et al. (2011). Identification of Extraterrestrial Peridot by trace elements, Gems & Gemology, p. 208-213

- St. John's Island peridot information and history at Mindat.org

- "Although some good olive-colored crystals are found in a few other places, like Burma, China, Zambia, and Pakistan, ninety percent of all known peridots are found in just one place. It is a Native American reservation, and it is located in a little-visited corner of the United States. San Carlos" Finlay, Victoria. Jewels: A Secret History (Kindle Locations 2543-2546). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

- Leelawatanasuk, Thanong; Atichat, Wilawan; Thye Sun, Tay; Sriprasert, Boontawee; Jakkawanvibul, Jirapit (2014). "Some Characteristics of Taaffeite from Myanmar". The Journal of Gemmology. 34 (2): 144–148. doi:10.15506/jog.2014.34.2.144. ISSN 1355-4565.

- Koivula, John I.; Fryer, C. W. (1986-04-01). "The Gemological Characteristics of Chinese Peridot". Gems & Gemology. 22 (1): 38–40. doi:10.5741/GEMS.22.1.38. ISSN 0016-626X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peridot. |