Celtic nations

The Celtic nations is a cultural region and collection of geographical territories in Western Europe and the North Atlantic where Celtic languages and/or cultural traits have survived.[1] The term "nation" is used in its original sense to mean a people who share a common identity and culture and are identified with a traditional territory.

The Celtic Nations | |

|---|---|

| |

| Languages | |

| Nations | |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 19,597,212 |

The six territories widely considered Celtic nations are Brittany (Breizh), Cornwall (Kernow), Wales (Cymru), Scotland (Alba), Ireland (Éire) and the Isle of Man (Mannin or Ellan Vannin).[1][2] In each of the six nations a Celtic language is spoken to some extent: Brittonic or Brythonic languages are spoken in Brittany, Cornwall, and Wales, while Goidelic or Gaelic languages are spoken in Scotland, Ireland, and the Isle of Man.[3]

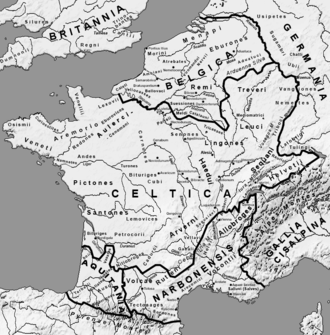

Before the expansions of Ancient Rome and the Germanic and Slavic tribes, a significant part of Europe was dominated by Celts, leaving behind a legacy of Celtic cultural traits.[4] Territories in north-western Iberia—particularly northern Portugal, Galicia, Asturias, León and Cantabria (together historically referred to as Gallaecia and Astures), covering north-central Portugal and northern Spain—are considered Celtic nations due to their culture and history.[5] Unlike the others, however, no Celtic language has been spoken there in modern times.[5][6][7]

A genetics study by an Oxford University research team in 2006 claimed that the majority of Britons, including many of the English, are descended from a group of tribes which arrived from Iberia around 5000 BC, before the spread of Celts into western Europe.[4] However, three major genetic studies in 2015 have instead shown that haplogroup R1b in western Europe, most common in traditionally Celtic-speaking areas of Atlantic Europe like Ireland and Brittany, would have largely expanded in massive migrations from the Indo-European homeland, the Yamnaya culture in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, during the Bronze Age along with carriers of Indo-European languages like proto-Celtic. Unlike previous studies, large sections of autosomal DNA were analyzed in addition to paternal Y-DNA markers. They detected an autosomal component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic or Mesolithic Europeans, and which would have been introduced into Europe with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as the Indo-European languages. This genetic component, labelled as "Yamnaya" in the studies, then mixed to varying degrees with earlier Mesolithic hunter-gatherer and/or Neolithic farmer populations already existing in western Europe.[8][9][10] Furthermore, a 2016 study also found that Bronze Age remains from Rathlin Island in Ireland dating to over 4,000 years ago were most genetically similar to modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh, and that the core of the genome of insular Celtic populations was established by this time.[11]

Six Celtic nations

Each of the six nations has its own Celtic language. In Wales, Ireland, Brittany, and Scotland these have been spoken continuously through time, while Cornwall and the Isle of Man have languages that were spoken into modern times but later died as spoken community languages.[12][13] In the latter two regions, however, language revitalisation movements have led to the adoption of these languages by adults and produced a number of native speakers.[14]

Ireland, Wales, Brittany and Scotland contain areas where a Celtic language is used on a daily basis; in Ireland the area (on the west coast) is called the Gaeltacht; in Wales Y Fro Gymraeg, and in Brittany Breizh-Izel.[15] Generally these communities are in the west of their countries and in more isolated upland or island areas. The term Gàidhealtachd historically distinguished the Gaelic-speaking areas of Scotland (the Highlands) from the Lowland Scots (i.e. Anglo-Saxon-speaking) areas. More recently, this term has also been adopted as the Gaelic name of the Highland council area, which includes non-Gaelic speaking areas. Hence, more specific terms such as sgìre Ghàidhlig ("Gaelic-speaking area") are now used.

In Wales, the Welsh language is a core curriculum (compulsory) subject, which all pupils study.[16] Additionally, 20% of schoolchildren in Wales attend Welsh medium schools, where they are taught entirely in the Welsh language.[17] In the Republic of Ireland, all school children study Irish as one of the three core subjects until the end of secondary school, and 7.4% of primary school education is through Irish medium education, which is part of the Gaelscoil movement.[17] In the Isle of Man, there is one Manx-medium primary school, and all schoolchildren have the opportunity to learn Manx.

Other territories

Parts of the northern Iberian Peninsula, namely Galicia, Cantabria, Asturias and Northern Portugal, also lay claim to this heritage.[5] Musicians from Galicia and Asturias have participated in Celtic music festivals, such as the Ortigueira's Festival of Celtic World in the village of Ortigueira or the Breton Festival Interceltique de Lorient, which in 2013 celebrated the Year of Asturias, and in 2019 celebrated the Year of Galicia.[18] Northern Portugal, part of ancient Gallaecia (Galicia, Minho, Douro and Trás-os-Montes), also has traditions quite similar to Galicia.[5] However, no Celtic language has been spoken in northern Iberia since probably the Early Middle Ages.[19][20]

Irish was once widely spoken on the island of Newfoundland, but had largely disappeared there by the early 20th century. Vestiges remain in some words found in Newfoundland English, such as scrob for "scratch", and sleveen for "rascal"[21] There are no fluent speakers of Irish Gaelic in Newfoundland or Labrador today. Knowledge seems to be largely restricted to memorized passages, such as traditional tales and songs.[21]

Canadian Gaelic dialects of Scottish Gaelic are still spoken by Gaels in other parts of Atlantic Canada, primarily on Cape Breton Island and adjacent areas of Nova Scotia. In 2011, there were 1,275 Gaelic speakers in Nova Scotia,[22] and 300 residents of the province considered a Gaelic language to be their "mother tongue".[23]

Patagonian Welsh is spoken principally in Y Wladfa in the Chubut Province of Patagonia, with sporadic speakers elsewhere in Argentina. Estimates of the number of Welsh speakers range from 1,500[24] to 5,000.[25]

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages form a branch of the greater Indo-European language family. SIL Ethnologue lists six living Celtic languages, of which four have retained a substantial number of native speakers. These are the Goidelic languages (i.e. Irish and Scottish Gaelic, which are both descended from Middle Irish) and the Brittonic languages (i.e. Welsh and Breton, which are both descended from Common Brittonic).[26]

The other two, Cornish (a Brittonic language) and Manx (a Goidelic language), died in modern times with their presumed last native speakers in 1777 and 1974 respectively. For both these languages, however, revitalisation movements have led to the adoption of these languages by adults and children and produced some native speakers.

Taken together, there were roughly one million native speakers of Celtic languages as of the 2000s. In 2010, there were more than 1.4 million speakers of Celtic languages.[27]

The chart below shows the population of each Celtic nation and the number of people in each nation who can speak Celtic languages. The total number of people living in the Celtic nations is 19,596,000 people and, of these, the total number of people who can speak the Celtic languages is approximately 2,818,000 or 14.3%.

| Nation | Celtic name | Celtic language | People | Population | Competent speakers | Percentage of population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Éire | Irish (Gaeilge) |

Irish (Éireannaigh, Gaeil) |

6,399,115 | 1,944,353 total: | 29.7%

| |

| Alba | Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) |

Scottish (Albannaich) |

5,429,600 | 92,400[31] | 1.2%[32] | |

| Breizh | Breton (Brezhoneg) |

Bretons (Breizhiz) |

4,300,000 | 206,000[33] | 5%[33] | |

| Cymru | Welsh (Cymraeg) |

Welsh (Cymry) |

3,200,000 | 750,000+ total: | 21.7%[39] | |

| Kernow | Cornish (Kernowek) |

Cornish (Kernowyon) |

500,000 | 2,000[40] | 0.1%[41][42] | |

| Mannin, Ellan Vannin |

Manx (Gaelg) |

Manx (Manninee) |

84,497[43] | 1,662[43] | 2.0%[43] |

- 1 The flag of the Republic of Ireland is used by the Celtic League[44] to represent Ireland, although there is no universally accepted flag for the whole of the island.

Celtic identity

Formal cooperation between the Celtic nations is active in many contexts, including politics, languages, culture, music and sports:

The Celtic League is an inter-Celtic political organisation, which campaigns for the political, language, cultural and social rights, affecting one or more of the Celtic nations.[45]

Established in 1917, the Celtic Congress is a non-political organisation that seeks to promote Celtic culture and languages and to maintain intellectual contact and close cooperation between Celtic peoples.[46]

Festivals celebrating the culture of the Celtic nations include the Festival Interceltique de Lorient (Brittany), the Pan Celtic Festival (Ireland), CeltFest Cuba (Havana, Cuba), the National Celtic Festival (Portarlington, Australia), the Celtic Media Festival (showcasing film and television from the Celtic nations), and the Eisteddfod (Wales).[7][47][48][49]

Inter-Celtic music festivals include Celtic Connections (Glasgow), and the Hebridean Celtic Festival (Stornoway).[50][51] Due to immigration, a dialect of Scottish Gaelic (Canadian Gaelic) is spoken by some on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, while a Welsh-speaking minority exists in the Chubut Province of Argentina. Hence, for certain purposes—such as the Festival Interceltique de Lorient—Gallaecia, Asturias, and Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia are considered three of the nine Celtic nations.[7]

Competitions are held between the Celtic nations in sports such as rugby union (Pro14—formerly known as the Celtic League), athletics (Celtic Cup) and association football (the Nations Cup—also known as the Celtic Cup).[52][53]

The Republic of Ireland enjoyed a period of rapid economic growth between 1995–2007, leading to the use of the phrase Celtic Tiger to describe the country.[54][55] Aspirations for Scotland to achieve a similar economic performance to that of Ireland led the Scotland First Minister Alex Salmond to set out his vision of a Celtic Lion economy for Scotland, in 2007.[56]

Terminology

The term "Celtic nations" derives from the linguistics studies of the 16th century scholar George Buchanan and the polymath Edward Lhuyd.[57] As Assistant Keeper and then Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (1691–1709), Lhuyd travelled extensively in Great Britain, Ireland and Brittany in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Noting the similarity between the languages of Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, which he called "P-Celtic" or Brythonic, the languages of Ireland, the Isle of Man and Scotland, which he called "Q-Celtic" or Goidelic, and between the two groups, Lhuyd published Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland in 1707. His Archaeologia Britannica concluded that all six languages derived from the same root. Lhuyd theorised that the root language descended from the languages spoken by the Iron Age tribes of Gaul, whom Greek and Roman writers called Celtic.[58] Having defined the languages of those areas as Celtic, the people living in them and speaking those languages became known as Celtic too. There is some dispute as to whether Lhuyd's theory is correct. Nevertheless, the term "Celtic" to describe the languages and peoples of Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, Ireland, the Isle of Man and Scotland was accepted from the 18th century and is widely used today.[57]

These areas of Europe are sometimes referred to as the "Celt belt" or "Celtic fringe" because of their location generally on the western edges of the continent, and of the states they inhabit (e.g. Brittany is in the northwest of France, Cornwall is in the south west of Great Britain, Wales in western Great Britain and the Gaelic-speaking parts of Ireland and Scotland are in the west of those countries).[59][60] Additionally, this region is known as the "Celtic Crescent" because of the near crescent shaped position of the nations in Europe.[61]

Endonyms and Celtic exonyms

The Celtic names for each nation in each language illustrate some of the similarity between the languages. Despite differences in orthography, there are many sound and lexical correspondences between the endonyms and exonyms used to refer to the Celtic nations.

| English | Breton (Brezhoneg) | Irish[62] (Gaeilge) | Scottish Gaelic[63] (Gàidhlig) | Welsh (Cymraeg) | Manx (Gaelg) | Cornish[64] (Kernowek) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brittany | Breizh [bʁɛjs] or [bʁɛχ] | an Bhriotáin [ən̪ˠ ˈvʲɾʲit̪ˠaːnʲ] | a' Bhreatainn Bheag [əˈvɾʲɛhdəɲ ˈveg] | Llydaw [ˈɬədau̯] | yn Vritaan | Breten Vian |

| Cornwall | Kernev-Veur [ˈkɛʁnev ˈvøːr] |

Corn na Breataine [ˈkoɾˠn̪ˠ n̪ˠə ˈbʲɾʲat̪ˠənʲə] | a' Chòrn [əˈxoːɾn] | Cernyw [ˈkʰɛrnɨu̯] | yn Chorn | Kernow |

| Ireland | Iwerzhon [iˈwɛʁzɔ̃n] | Éire [ˈeːɾʲə] |

Èirinn [ˈeːrʲɪɲʲ] | Iwerddon [iˈwɛrðon] | Nerin | Wordhen Iwerdhon |

| Mann Isle of Man | Manav [mɑ̃ˈnaw] Enez-Vanav [ˈẽːnes vɑ̃ˈnaw] | Manainn [ˈmˠan̪ˠən̪ʲ] Oileán Mhanann [ˈilʲaːn̪ˠ ˈvˠan̪ˠən̪ˠ] | Manainn [ˈmanɪɲ] Eilean Mhanainn [elanˈvanɪɲ] |

Manaw [ˈmanau̯] Ynys Manaw [ˈənɨs ˈmanau̯] | Mannin [ˈmanɪn] Ellan Vannin |

Manow Enys Vanow |

| Scotland | Bro-Skos [ˈbʁo ˈskos] Skos [skos] | Albain [ˈaləbˠənʲ] | Alba [ˈal̪ˠapə] | yr Alban [ər ˈalban] |

Nalbin | Alban |

| Wales | Kembre [ˈkɛ̃m.bʁe] |

an Bhreatain Bheag [ən̪ˠ ˈvʲɾʲat̪ˠənʲ ˈvʲəɡ] | a' Chuimrigh [ə'xɯmurɪ] | Cymru [ˈkʰəmrɨ] | Bretin | Kembra |

| Celtic nations | broioù keltiek [ˈbʁoju ˈkɛltjɛk] | náisiúin Cheilteacha [ˈn̪ˠaːʃuːnʲ ˈçelʲtʲəxə] | nàiseanan Ceilteach [ˈnˠaːʃanən ˈkʲeldʲəx] | gwledydd Celtaidd [gʷˈlei̯ð ˈkʰɛltʰai̯ð] | ashoonyn Celtiagh | broyow keltek |

| Celtic languages | yezhoù keltiek [ˈjeːsu ˈkɛltjɛk] | teangacha Ceilteacha [ˈtʲaŋɡəxə ˈçelʲtʲəxə] | cànanain Cheilteach [ˈkaːnanɪɲ ˈçʲeldʲəx] | ieithoedd Celtaidd [ˈjei̯θɔɨ̯ð ˈkʰɛltʰai̯ð] | çhengaghyn Celtiagh | yethow keltek |

| Great Britain | Breizh-Veur [ˈbʁɛjs ˈvøːr] | an Bhreatain Mhór [ən̪ˠ ˈvʲɾʲat̪ˠənʲ ˈvˠoːɾˠ] | Breatainn Mhòr [əˈvɾʲɛhdəɲ ˈvoːɾ] | Prydain Fawr [ˈpr̥ətʰai̯n ˈvau̯r] | Bretin Vooar | Breten Veur |

Territories of the ancient Celts

During the European Iron Age, the ancient Celts extended their territory to most of Western and Central Europe and part of Eastern Europe and central Anatolia.

The Continental Celtic languages were extinct by the Early Middle Ages, and the continental "Celtic cultural traits", such as an oral traditions and practices like the visiting of sacred wells and springs, largely disappeared or, in some cases, were translated. Since they no longer have a living Celtic language, they are not included as 'Celtic nations'. Nonetheless, some of these countries have movements claiming a "Celtic identity"

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula was an area heavily influenced by Celtic culture, particularly the ancient region of Gallaecia (about the modern region of Galicia and Braga, Viana do Castelo, Douro, Porto, and Bragança in Portugal) and the Asturian region (Asturias, León, Zamora in Spain). Only France and Britain have more ancient Celtic place names than Spain and Portugal combined (Cunliffe and Koch 2010 and 2012).

Some of the Celtic tribes recorded in these regions by the Romans were the Gallaeci, the Bracari, the Astures, the Cantabri, the Celtici, the Celtiberi, the Tumorgogi, Albion and Cerbarci. The Lusitanians are categorised by some as Celts, or at least Celticised, but there remain inscriptions in an apparently non-Celtic Lusitanian language. However, the language had clear affinities with the Gallaecian Celtic language. Modern-day Galicians, Asturians, Cantabrians and northern Portuguese claim a Celtic heritage or identity.[5] Although the Celtic cultural traces are as difficult to analyse as in the other former Celtic countries of Europe, because of the extinction of Iberian Celtic languages in Roman times, Celtic heritage is attested in toponymics and language substratum, ancient texts, folklore and music.[5][66] At the end, late Celtic influence is also attributed to the fifth century Romano-Briton colony of Britonia in Galicia.

Tenth century Middle Irish mythical history Lebor Gabála Érenn (Irish: Leabhar Gabhála Éireann) credited Gallaecia as the point from where the Gallaic Celts sailed to conquer Ireland.

England

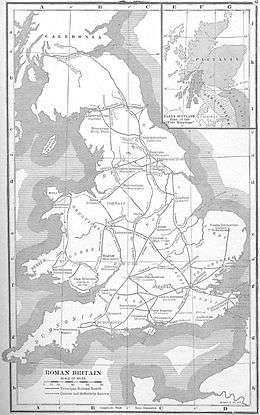

In Celtic languages, England is usually referred to as "Saxon-land" (Sasana, Pow Sows, Bro-Saoz etc.), and in Welsh as Lloegr (though the Welsh translation of English also refers to the Saxon route: Saesneg, with the English people being referred to as "Saeson", or "Saes" in the singular). The mildly derogatory Scottish Gaelic term Sassenach derives from this source. However, spoken Cumbric survived until approximately the 12th century, Cornish until the 18th century, and Welsh within the Welsh Marches, notably in Archenfield, now part of Herefordshire, until the 19th century. Both Cumbria and Cornwall were traditionally Brythonic in culture. Cornwall existed as an independent state for some time after the foundation of England, and Cumbria originally retained a great deal of autonomy within the Kingdom of Northumbria. The unification of the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria with the Cumbric kingdom of Cumbria came about due to a political marriage between the Northumbrian King Oswiu and Queen Riemmelth (Rhiainfellt in Old Welsh), a then Princess of Rheged.

Movements of population between different parts of Great Britain over the last two centuries, with industrial development and changes in living patterns such as the growth of second home ownership, have greatly modified the demographics of these areas, including the Isles of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall, although Cornwall in particular retains Celtic cultural features, and a Cornish self-government movement is well established.[67]

Brythonic and Cumbric placenames are found throughout England but are more common in the West of England than the East, reaching their highest density in the traditionally Celtic areas of Cornwall, Cumbria and the areas of England bordering Wales. Name elements containing Brythonic topographic words occur in many areas of England, such as: caer 'fort', as in the Cumbrian city of Carlisle; pen 'hill' as in the Cumbrian town of Penrith and Pendle Hill in Lancashire; afon 'river' as in the Rivers Avon in Warwickshire, Devon and Somerset; and mynydd 'mountain', as in Long Mynd in Shropshire. The name 'Cumbria' is derived from the same root as Cymru, the Welsh name for Wales, meaning 'the land of comrades'.

Formerly Gaulish regions

Most French people identify with the ancient Gauls and are well aware that they were a people that spoke Celtic languages and lived Celtic ways of life.[68] Nowadays, the popular nickname Gaulois, "Gaulish people", is very often used to mean 'stock French people' to make the difference with the descendants of foreigners in France.

Walloons occasionally characterise themselves as "Celts", mainly in opposition to the "Teutonic" Flemish and "Latin" French identities.[69] Others think they are Belgian, that is to say Germano-Celtic people different from the Gaulish-Celtic French.[69]

The ethnonym "Walloon" derives from a Germanic word meaning "foreign", cognate with the words "Welsh" and "Vlach". The name of Belgium, home country of the Walloon people, is cognate with the Celtic tribal names Belgae and (possibly) the Irish legendary Fir Bolg.

Italian Peninsula

The Canegrate culture (13th century BC) may represent the first migratory wave of the proto-Celtic[70] population from the northwest part of the Alps that, through the Alpine passes, had already penetrated and settled in the western Po valley between Lake Maggiore and Lake Como (Scamozzina culture). It has also been proposed that a more ancient proto-Celtic presence can be traced back to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (16th–15th century BC), when North Westwern Italy appears closely linked regarding the production of bronze artifacts, including ornaments, to the western groups of the Tumulus culture (Central Europe, 1600–1200 BC).[71] La Tène cultural material appeared over a large area of mainland Italy,[72] the southernmost example being the Celtic helmet from Canosa di Puglia.[73]

Italy is home to the Lepontic, the oldest attested Celtic language (from the 6th century BC).[74] Anciently spoken in Switzerland and in Northern-Central Italy, from the Alps to Umbria.[75][76][77][78] According to the Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises, more than 760 Gaulish inscriptions have been found throughout present-day France—with the notable exception of Aquitaine—and in Italy,[79][80] which testifies the importance of Celtic heritage in the peninsula.

The French- and Arpitan-speaking Aosta Valley region in Italy also presents a claim of Celtic heritage.[81] The Northern League autonomist party often exalts what it claims are the Celtic roots of all Northern Italy or Padania.[82] Reportedly, Friuli also has a claim to Celticity (recent studies have estimated that about 1/10 of Friulian words are of Celtic origin; also, a lot of typical Friulian traditions, dances, songs and mythology are remnants of the culture of Carnian tribes who lived in this area during the Roman age and the early Middle Ages. Some Friulians consider themselves and their region as one of the Celtic Nations[83])

Central and Eastern European regions

Celtic tribes inhabited land in what is now southern Germany and Austria.[84] Many scholars have associated the earliest Celtic peoples with the Hallstatt culture.[85] The Boii, the Scordisci,[86] and the Vindelici[87] are some of the tribes that inhabited Central Europe, including what is now Slovakia, Serbia, Croatia, Poland and the Czech Republic as well as Germany and Austria. The Boii gave their name to Bohemia.[88] The Boii founded a city on the site of modern Prague, and some of its ruins are now a tourist attraction.[89] There are claims among modern Czechs that the Czech people are as much descendants of the Boii as they are from the later Slavic invaders (as well as the historical Germanic peoples of Czech lands). This claim may not only be political: according to a 2000 study by Semino, 35.6% of Czech males have y-chromosome haplogroup R1b,[90] which is common among Celts but rare among Slavs. Celts also founded Singidunum near present-day Belgrade, though the Celtic presence in modern-day Serbian regions is limited to the far north (mainly including the historically at least partially Hungarian Vojvodina). The modern-day capital of Turkey, Ankara, was once the center of the Celtic culture in Central Anatolia, giving the name to the region—Galatia. The La Tène culture—named for a region in modern Switzerland—succeeded the Halstatt era in much of central Europe.[91]

Celtic diaspora

In other regions, people with a heritage from one of the Celtic nations also associate with the Celtic identity. In these areas, Celtic traditions and languages are significant components of local culture. These include the Permanent North American Gaeltacht in Tamworth, Ontario, Canada which is the only Irish Gaeltacht outside Ireland; the Chubut valley of Patagonia with Welsh-speaking Welsh Argentines (known as Y Wladfa); Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, with Scottish Gaelic-speaking Scottish Canadians; and southeast Newfoundland with traditionally Irish-speaking Irish Canadians. Also at one point in the 1900s there were well over 12,000 Gaelic Scots from the Isle of Lewis living in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, Canada, with place names that still exist today recalling those inhabitants.

Saint John, New Brunswick has often been called "Canada's Irish City". In the years between 1815, when vast industrial changes began to disrupt the old life-styles in Europe, and Canadian Confederation in 1867, when immigration of that era passed its peak, more than 150,000 immigrants from Ireland flooded into Saint John. Those who came in the earlier period were largely tradesmen, and many stayed in Saint John, becoming the backbone of its builders. But when the Great Irish Potato Famine raged between 1845–1852, huge waves of Famine refugees flooded these shores. It is estimated that between 1845 and 1847, some 30,000 arrived, more people than were living in the city at the time. In 1847, dubbed "Black 47," one of the worst years of the Famine, some 16,000 immigrants, most of them from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island, the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour. However, thousands of Irish were living in New Brunswick prior to these events, mainly in Saint John.[92]

After the partitioning of the British colony of Nova Scotia in 1784 New Brunswick was originally named New Ireland with the capital to be in Saint John.[93]

Large swathes of the United States of America were subject to migration from Celtic peoples, or people from Celtic nations. Irish-speaking Irish Catholics congregated particularly in the East Coast cities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, and also in Pittsburgh and Chicago, while Scots and Ulster-Scots were particularly prominent in the Southern United States, including Appalachia. Gaelic speaking Highland-Scots also migrated in concentrated numbers to the Cape Fear River area in North Carolina and the fortress-town of Darien, Georgia.

A legend that became popular during the Elizabethan era claims that a Welsh prince named Madoc established a colony in North America in the late 12th century. The story continues that the settlers merged with local Indian tribes, who preserved the Welsh language and the Christian religion for hundreds of years.[94] However, there is no contemporary evidence that Prince Madoc existed. An area of Pennsylvania known as the Welsh Tract was settled by Welsh Quakers, where the names of several towns still bear Welsh names, such as Bryn Mawr, the Lower and Upper Gwynedd Townships, and Bala Cynwyd. In the 19th century, Welsh settlers arrived in the Chubut River valley of Patagonia, Argentina and established a colony called Y Wladfa (Spanish: Colonia Galesa). Today, the Welsh language and Welsh tea houses are common in several towns, many of which have Welsh names. Dolavon and Trelew are examples of Welsh towns.

In his autobiography, the South African poet Roy Campbell recalled his youth in the Dargle Valley, near the city of Pietermaritzburg, where people spoke only Gaelic and Zulu.

In New Zealand, the southern regions of Otago and Southland were settled by the Free Church of Scotland. Many of the place names in these two regions (such as the main cities of Dunedin and Invercargill and the major river, the Clutha) have Scottish Gaelic names,[95] and Celtic culture is still prominent in this area.[96][97][98]

In addition to these, a number of people from Canada, the United States, Australia, South Africa and other parts of the former British Empire have formed various Celtic societies over the years.

See also

- Anglo-Celtic

- Breton nationalism

- Celt

- Celtic Christianity

- Celtic Revival

- Celtic art

- Celtic fusion

- Celtic mythology

- Galician nationalism

- Germanic languages

- Irish nationalism

- Pan-Celticism

- Romance-speaking Europe

- Scottish national identity

- Slavic Europe

- Welsh nationalism

References

- Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture : A Historical Encyclopedia. ABL-CIO. pp. xx, 300, 421, 495, 512, 583, 985. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- "Constitution of the League". The Celtic League. 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 365. ISBN 9781851094400. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- Ian Johnston (21 September 2006). "We're nearly all Celts under the skin". The Scotsman. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- Alberro, Manuel (2005). "Celtic Legacy in Galicia". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 1005–1035.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 365, 697, 788–791. ISBN 9781851094400. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- "Site Officiel du Festival Interceltique de Lorient". Festival Interceltique de Lorient website. Festival Interceltique de Lorient. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei; Mittnik, Alissa; Bánffy, Eszter; Economou, Christos; Francken, Michael; Friederich, Susanne; Pena, Rafael Garrido; Hallgren, Fredrik; Khartanovich, Valery; Khokhlov, Aleksandr; Kunst, Michael; Kuznetsov, Pavel; Meller, Harald; Mochalov, Oleg; Moiseyev, Vayacheslav; Nicklisch, Nicole; Pichler, Sandra L.; Risch, Roberto; Rojo Guerra, Manuel A.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". bioRxiv. 522 (7555): 013433. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1101/013433.

- Allentoft, Morten E.; Sikora, Martin; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Rasmussen, Simon; Rasmussen, Morten; Stenderup, Jesper; Damgaard, Peter B.; Schroeder, Hannes; Ahlström, Torbjörn; Vinner, Lasse; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Margaryan, Ashot; Higham, Tom; Chivall, David; Lynnerup, Niels; Harvig, Lise; Baron, Justyna; Casa, Philippe Della; Dąbrowski, Paweł; Duffy, Paul R.; Ebel, Alexander V.; Epimakhov, Andrey; Frei, Karin; Furmanek, Mirosław; Gralak, Tomasz; Gromov, Andrey; Gronkiewicz, Stanisław; Grupe, Gisela; Hajdu, Tamás; et al. (2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507.

- Mathieson, Iain; Lazaridis, Iosif; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Patterson, Nick; Alpaslan Roodenberg, Songul; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fernandes, Daniel; Novak, Mario; Sirak, Kendra; Gamba, Cristina; Jones, Eppie R.; Llamas, Bastien; Dryomov, Stanislav; Pickrell, Joseph; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; De Castro, Jose Maria Bermudez; Carbonell, Eudald; Gerritsen, Fokke; Khokhlov, Aleksandr; Kuznetsov, Pavel; Lozano, Marina; Meller, Harald; Mochalov, Oleg; Moiseyev, Vayacheslav; Rojo Guerra, Manuel A.; Roodenberg, Jacob; Verges, Josep Maria; et al. (2015). "Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe". bioRxiv: 016477. doi:10.1101/016477.

- Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome "Three Bronze Age individuals from Rathlin Island (2026–1534 cal BC), including one high coverage (10.5×) genome, showed substantial Steppe genetic heritage indicating that the European population upheavals of the third millennium manifested all of the way from southern Siberia to the western ocean. This turnover invites the possibility of accompanying introduction of Indo-European, perhaps early Celtic, language. Irish Bronze Age haplotypic similarity is strongest within modern Irish, Scottish, and Welsh populations, and several important genetic variants that today show maximal or very high frequencies in Ireland appear at this horizon. These include those coding for lactase persistence, blue eye color, Y chromosome R1b haplotypes, and the hemochromatosis C282Y allele; to our knowledge, the first detection of a known Mendelian disease variant in prehistory. These findings together suggest the establishment of central attributes of the Irish genome 4,000 y ago."

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 34, 365–366, 529, 973, 1053. ISBN 9781851094400. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- Beresford Ellis, Peter (1990). The Story of the Cornish Language. Tor Mark Press. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-0-85025-371-9.

- "Fockle ny ghaa: schoolchildren take charge". Iomtoday.co.im. 20 March 2008. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "www.breizh.net/icdbl/saozg/Celtic_Languages.pdf" (PDF). Breizh.net website. U.S. Branch of the International Committee for the Defense of the Breton Language. 1995. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- "The School Gate – About School – The Curriculum at Primary School". BBC website. BBC Wales. 20 February 2010. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Local UK languages 'taking off'". BBC News website. BBC News: Education. 12 February 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Les nations celtes". 43e Festival Interceltique de Lorient (in French). Archived from the original on 12 June 2011.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851094400.

- Koch, John T. (2006). "Britonia". In John T. Koch, Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, p. 291.

- Language: Irish Gaelic, Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage website.

- Statistics Canada, NHS Profile 2011, by province.

- Statistics Canada, 2011 Census of Canada, Table: Detailed mother tongue

- Western Mail (Cardiff, Wales). 27 Dec 2004. Patagonia Welsh to watch S4C shows. Archived 17 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Wales and Patagonia". Wales.com website. Welsh Assembly Government. 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Glottolog - Celtic Languages". Glottolog. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Crystal, David (2010). The Cambridge encyclopedia of language (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521516983. OCLC 499073732.

- The 2011 population of the Republic of Ireland was 4,588,252 and that of Northern Ireland in 2011 was 1,810,863. These are Census data from the official governmental statistics agencies in the respective jurisdictions:

- Central Statistics Office, Dublin

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (2008). "Population and Migration Estimates Northern Ireland (2008)" (PDF). Belfast: Department of Finance and Personnel. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- "Central Statistics Office Ireland". Cso.ie. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- The figure for Northern Ireland from the 2001 Census is somewhat ambiguous, as it covers people who have "some knowledge of Irish". Out of the 167,487 people who claimed to have "some knowledge", 36,479 of them could understand it when spoken, but couldn't speak it themselves.

- "Mixed report on Gaelic language". BBC News. 10 October 2005. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Kenneth MacKinnon (2003). "Census 2001 Scotland: Gaelic Language – first results". Archived from the original on 4 September 2006. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- (in French) Données clés sur Breton, Ofis ar Brezhoneg

- "2004 Welsh Language Use Survey: the report – Welsh Language Board". Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – United Kingdom : Welsh". UNHCR. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Wales and Argentina". Wales.com website. Welsh Assembly Government. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- "Table 1. Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over for the United States: 2006–2008 Release Date: April, 2010" (xls). United States Census Bureau. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- "2006 Census of Canada: Topic based tabulations: Various Languages Spoken (147), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data". Statistics Canada. 7 December 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- "Publication of the report on the 2004 Welsh Language Use Survey". Welsh Language Board website An increase from the 2001 census results: 582,368 persons age 3 and over were able to speak Welsh – 20.8% of the population. Welsh Language Board. 8 May 2006. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- "'South West:TeachingEnglish:British Council:BBC". BBC/British Council website. BBC. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- projects.ex.ac.uk – On being a Cornish ‘Celt’: changing Celtic heritage and traditions Archived 18 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Effectively extinct as a spoken language in 1777. Language revived from 1904, though a tiny 0.1% percent is able to hold a limited conversion in Cornish.

- "Isle of Man Census 2011" (PDF). Isle of Man Government. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- https://www.celticleague.net/eire/

- "The Celtic League". Celtic League website. The Celtic League. 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Information on The International Celtic Congress Douglas, Isle of Man hosted by". Celtic Congress website (in Irish and English). Celtic Congress. 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Welcome to the Pan Celtic 2010 Home Page". Pan Celtic Festival 2010 website. Fáilte Ireland. 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "About the Festival". National Celtic Festival website. National Celtic Festival. 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "About Us: Celtic Media Festival". Celtic Media Festival website. Celtic Media Festival. 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- "Celtic connections:Scotland's premier winter music festival". Celtic connections website. Celtic Connections. 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "'Hebridean Celtic Festival 2010 – the biggest homecoming party of the year". Hebridean Celtic Festival website. Hebridean Celtic Festival. 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Magners League: About Us". Magners League website. Celtic League. 2009. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "scottishathletics-news". scottishathletics website. Scottish Athletics. 14 June 2006. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- Coulter, Colin; Coleman, Steve (2003). The end of Irish history?: critical reflections on the Celtic tiger. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7190-6230-8. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- ""Celtic Tiger" No More – CBS Evening News". CBS News website. CBS Interactive. 7 March 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Salmond gives Celtic Lion vision". BBC News website. BBC News: Scotland. 12 October 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

- "Who were the Celts? ... Rhagor". Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales website. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- Lhuyd, Edward (1707). Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland. Oxford.

- Nathalie Koble, Jeunesse et genèse du royaume arthurien, Paradigme, 2007, ISBN 2-86878-270-1, p. 145

- The term "Celtic Fringe" gained currency in late-Victorian years (Thomas Heyck, A History of the Peoples of the British Isles: From 1870 to Present, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-30233-1, p. 43) and is now widely attested, e.g. Michael Hechter, Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, Transaction Publishers, 1999, ISBN 0-7658-0475-1; Nicholas Hooper and Matthew Bennett, England and the Celtic Fringe: Colonial Warfare in The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-521-44049-1

- Ian Hazlett, The Reformation in Britain and Ireland, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0-567-08280-6, p. 21

- "Phonetics and Speech Laboratory - Trinity College". Abair.ie. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "LearnGaelic Dictionary". Learn Gaelic. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "An English-Cornish Glossary in the Standard Written Form". Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Ethnographic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (circa 200 b". Arkeotavira.com. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Melhuish, Martin (1998). Celtic Tides: Traditional Music in a New Age. Ontario, Canada: Quarry Press Inc. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-55082-205-2.

- The Kingdom of Kernow 'exists apart from England' – Telegraph.co.uk, 29 January 2010

- "What Is France? Who Are the French?". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Belgium: Flemings, Walloons and Germans". Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Venceslas Kruta: La grande storia dei celti. La nascita, l'affermazione e la decadenza, Newton & Compton, 2003, ISBN 88-8289-851-2, 978-88-8289-851-9

- "The Golasecca civilization is therefore the expression of the oldest Celts of Italy and included several groups that had the name of Insubres, Laevi, Lepontii, Oromobii (o Orumbovii)". (Raffaele C. De Marinis)

- "Manufatti in ferro di tipo La Tène in area italiana : le potenzialità non sfruttate".

- Piggott, Stuart (2008). Early Celtic Art From Its Origins to its Aftermath. Transaction Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-202-36186-4.

- Schumacher, Stefan; Schulze-Thulin, Britta; aan de Wiel, Caroline (2004). Die keltischen Primärverben. Ein vergleichendes, etymologisches und morphologisches Lexikon (in German). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Kulturen der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 84–87. ISBN 978-3-85124-692-6.

- Percivaldi, Elena (2003). I Celti: una civiltà europea. Giunti Editore. p. 82.

- Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 55.

- Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). p. 12.

- Morandi 2004, pp. 702–703, n. 277

- Peter Schrijver, "Gaulish", in Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe, ed. Glanville Price (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), 192.

- Landolfi, Maurizio (2000). Adriatico tra 4. e 3. sec. a.C. L'Erma di Bretschneider. p. 43.

- "Aosta Festival digs up Celtic roots in Italy". Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Celtica Festival 2009, Northern Italy". Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "KurMor Celtic Festival in Ara, Udine, Friuli, Italy". Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Celts – Hallstatt and La Tene cultures". Celts.etrusia.co.uk. 21 October 2005. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Celtic Impressions – The Celts Archived 24 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- AncientWorlds.net Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 27k

- authorName. "Vindelici". Ancientworlds.net. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Boii". Britannica.com. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Prague Celtic History Remains Route Celtic Walk in Prague". Prague.net. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- O. Semino et al., The genetic legacy of paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective, Science, vol. 290 (2000), pp. 1155–59.

- "The Early Celts". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Trouble in the North End: The Geography of Social Violence in Saint John 1840–1860". Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- "Winslow Papers: The Partition of Nova Scotia". lib.unb.ca.

- Catlin, G. Die Indianer Nordamerikas Verlag Lothar Borowsky

- "Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Te Ara. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Lewis, John (1 December 2008). "Regal poise amid 'Celtic' clime". Otago Daily Times. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- "DunedinCelticArts.org.nz". DunedinCelticArts.org.nz. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "OtagoCaledonian.org". OtagoCaledonian.org. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

Further reading

- O'Neill, Tom (March 2006). "The Celtic Realm". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

External links

- Celtic nations at Curlie

- Celtic League

- The Celtic Realm

- Celtic-World.Net – Various information on Celtic culture and music

- "National Geographic Map: The Celtic Realm" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2006. (306 KB)

- Simon James Ancient Celts Page

- an article on Celtic Realms by Jim Gilchrist of The Scotsman

- The Celtic Nations Association