Queensland

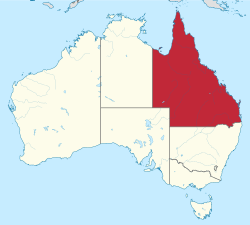

Queensland (locally /ˈkwiːnzlænd/ KWEENZ-land,[note 1] abbreviated as Qld) is the second-largest and third-most populous state in the Commonwealth of Australia. Situated in the north-east of the country, it is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean. To its north is the Torres Strait, with Papua New Guinea located less than 200 km across it from the mainland. The state is the world's sixth-largest sub-national entity, with an area of 1,852,642 square kilometres (715,309 sq mi).

| Queensland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Slogan or nickname | The Sunshine State | ||||

| Motto(s) | Audax at Fidelis (Bold but Faithful) | ||||

Location relative to other Australian states and territories | |||||

| Coordinates | 23°S 143°E | ||||

| Capital city | Brisbane | ||||

| Demonym | Queenslander | ||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||

| • Governor | Paul de Jersey | ||||

| • Premier | Annastacia Palaszczuk (ALP) | ||||

| Australian state | |||||

| • Separation from New South Wales | 6 June 1859 | ||||

| • Federation | 1901 | ||||

| • Australia Act | 3 March 1986 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| • Total | 1,852,642 km² (2nd) 715,309 sq mi | ||||

| • Land | 1,730,620 km² 668,196 sq mi | ||||

| • Water | 121,991 km² (6.58%) 47,101 sq mi | ||||

| Population (September 2019)[1] | |||||

| • Population | 5,115,451 (3rd) | ||||

| • Density | 2.96/km² (5th) 7.7 /sq mi | ||||

| Elevation | |||||

| • Highest point | Mount Bartle Frere 1,622 m (5,322 ft) | ||||

| Gross state product (2018–19) | |||||

| • Product ($m) | $357,044[2] (3rd) | ||||

| • Product per capita | $70,662 (5th) | ||||

| Time zone(s) | UTC+10 (AEST) | ||||

| Federal representation | |||||

| • House seats | 30/151 | ||||

| • Senate seats | 12/76 | ||||

| Abbreviations | |||||

| • Postal | QLD | ||||

| • ISO 3166-2 | AU-QLD | ||||

| Emblems | |||||

| • Floral | Cooktown orchid (Dendrobium phalaenopsis)[3] | ||||

| • Animal | Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) | ||||

| • Bird | Brolga (Grus rubicunda) | ||||

| • Fish | Barrier Reef anemonefish (Amphiprion akindynos) | ||||

| • Mineral or gemstone | Sapphire | ||||

| • Colours | Maroon (unofficial)[4] | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

Queensland has a population of over 5.1 million,[6] concentrated along the coast and particularly in the state's South East. The capital and largest city in the state is Brisbane, Australia's third-largest city. Often referred to as the "Sunshine State", Queensland is home to 10 of Australia's 30 largest cities and is the nation's third-largest economy. Tourism in the state, fuelled largely by its warm climate, is a major industry.

Queensland was first inhabited by Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders.[7][8] The first European to land in Queensland (and Australia) was Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon in 1606, who explored the west coast of the Cape York Peninsula near present-day Weipa. In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook claimed the east coast of Australia for the Kingdom of Great Britain. The colony of New South Wales was founded in 1788 by Governor Arthur Phillip at Sydney; New South Wales at that time included all of what is now Queensland, Victoria and Tasmania. Queensland was explored in subsequent decades until the establishment of a penal colony at Brisbane in 1824 by John Oxley. Penal transportation ceased in 1839 and free settlement was allowed from 1842.

The state was named in honour of Queen Victoria,[9] who signed on 6 June 1859 Letters Patent separating the colony from New South Wales. Queensland Day is celebrated annually statewide on 6 June. Queensland was one of the six colonies which became the founding states of Australia with federation on 1 January 1901.

History

The history of Queensland spans thousands of years, encompassing both a lengthy indigenous presence, as well as the eventful times of post-European settlement. The north-eastern Australian region was explored by Dutch, Spanish and French navigators before being encountered by Lieutenant James Cook in 1770. The state has witnessed frontier warfare between European settlers and Indigenous inhabitants (which did not result in any settlement or treaty), as well as the exploitation of cheap Kanaka labour sourced from the South Pacific through a form of forced recruitment known at the time as "blackbirding". The Australian Labor Party has its origin as a formal organisation in Queensland and the town of Barcaldine is the symbolic birthplace of the party.[10] June 2009 marked the 150th anniversary of its creation as a separate colony from New South Wales.[11] A rare record of early settler life in north Queensland can be seen in a set of ten photographic glass plates taken in the 1860s by Richard Daintree, in the collection of the National Museum of Australia.[12]

Arrival of Aboriginal Australians

The Aboriginal occupation of Queensland is thought to predate 50,000 BC, likely via boat or land bridge across Torres Strait, and became divided into over 90 different language groups.

During the last ice age Queensland's landscape became more arid and largely desolate, making food and other supplies scarce. This led to the world's first seed-grinding technology. Warming again made the land hospitable, which brought high rainfall along the eastern coast, stimulating the growth of the state's tropical rainforests.[13]

European arrival (1606)

In February 1606, Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon landed near the site of what is now Weipa, on the western shore of Cape York. This was the first recorded landing of a European in Australia, and it also marked the first reported contact between European and Aboriginal Australian people.[13] The region was also explored by French and Spanish explorers (commanded by Louis Antoine de Bougainville and Luís Vaez de Torres, respectively) prior to the arrival of Lieutenant James Cook in 1770. Cook claimed the east coast under instruction from King George III of the United Kingdom on 22 August 1770 at Possession Island, naming Eastern Australia, including Queensland, 'New South Wales'.[14]

The Aboriginal population declined significantly after a smallpox epidemic during the late 18th century.[15] (There has been controversy regarding the origins of smallpox in Australia; while many sources have claimed that it originated with British settlers, this theory has been contradicted by scientific evidence.[16][17][18] There is circumstantial evidence that Macassan mariners visiting Arnhem Land introduced smallpox to Australia.[17] )

In 1823, John Oxley, a British explorer, sailed north from what is now Sydney to scout possible penal colony sites in Gladstone (then Port Curtis) and Moreton Bay. At Moreton Bay, he found the Brisbane River. He returned in 1824 and established a settlement at what is now Redcliffe. The settlement, initially known as Edenglassie, was then transferred to the current location of the Brisbane city centre. Edmund Lockyer discovered outcrops of coal along the banks of the upper Brisbane River in 1825.[19] In 1839 transportation of convicts was ceased, culminating in the closure of the Brisbane penal settlement. In 1842 free settlement was permitted. In 1847, the Port of Maryborough was opened as a wool port. The first free immigrant ship to arrive in Moreton Bay was the Artemisia, in 1848. In 1857, Queensland's first lighthouse was built at Cape Moreton.

Frontier War

A war, sometimes called a "war of extermination",[20] erupted between Aborigines and settlers in colonial Queensland. The Frontier War was notable for being the most bloody in Australia, perhaps due to Queensland's larger pre-contact indigenous population when compared to the other Australian colonies. About 1,500 European settlers and their allies (consisting of Chinese, Aboriginal and Melanesian assistants), were killed in frontier skirmishes during the nineteenth century. Casualties among the Aboriginal people may have exceeded 30,000. The "Native Police Force", employed by the Queensland government, was key in the oppression of the indigenous people.[21]

On 27 October 1857, Aboriginals retaliating against being poisoned and raped by members of the Fraser family, attacked the Hornet Bank pastoral station on the Dawson River killing eleven people. This was one of the largest massacres of British colonists by Indigenous Australians.[22][23][24][25] The largest reported massacre of colonists by Aboriginals was in 1861 on the Nogoa River where 19 people were killed.[26] One author[27] estimates 24,000 Aboriginal men, women and children died at the hands of the Native Police in colonial Queensland between 1859 and 1897 alone.

Colony of Queensland

A public meeting was held in 1851 to consider the proposed separation of Queensland from New South Wales. On 6 June 1859, Queen Victoria signed Letters Patent to form the separate colony of what is now Queensland. Brisbane was appointed as the capital city. On 10 December 1859, a proclamation was read by British author George Bowen, whereby Queensland was formally separated from the state of New South Wales.[28] As a result, Bowen became the first Governor of Queensland. On 22 May 1860 the first Queensland election was held and Robert Herbert, Bowen's private secretary, was appointed as the first Premier of Queensland. Queensland also became the first Australian colony to establish its own parliament rather than spending time as a Crown Colony. In 1865, the first rail line in the state opened between Ipswich and Grandchester.

Queensland's economy expanded rapidly in 1867 after James Nash discovered gold on the Mary River near the town of Gympie, sparking a gold rush. While still significant, they were on a much smaller scale than the gold rushes of Victoria and New South Wales.

Immigration to Australia and Queensland in particular began in the 1850s to support the state economy. During the period from the 1860s until the early 20th century, many labourers, known at the time as Kanakas, were brought to Queensland from neighbouring Pacific Island nations to work in the state's sugar cane fields. Some of these people had been kidnapped under a process known as blackbirding or press ganging, and their employment conditions amounted to indentured labour or even slavery. Italians had entered the sugar cane industry as early as the 1890s.[29] During the Australian federation of 1901, the White Australia policy came into effect, which saw all foreign workers in Australia deported under the Pacific Island Labourers Act of 1901, which saw the Pacific Islander population of the state decrease rapidly.[30]

20th century

On 1 January 1901, Australia was federated following a proclamation by Queen Victoria. During this time, Queensland had a population of half a million people. Brisbane was subsequently proclaimed a city in 1902. In 1905, women voted in state elections for the first time, and the University of Queensland was established in 1909. In 1911, The first alternative treatments for polio were pioneered in Queensland and remain in use across the world today.

World War I had a major impact on Queensland. Over 58,000 Queenslanders fought in World War I and over 10,000 of them died.[31]

Australia's first major airline, Qantas, was founded in 1920 to serve outback Queensland.

In 1922, Queensland abolished the Upper House, becoming the only State with a unicameral State Parliament in Australia.

In 1935, cane toads were deliberately introduced to Queensland from Hawaii in a poorly-thought-out and unsuccessful attempt to reduce the number of French's cane and greyback cane beetles that were destroying the roots of sugar cane plants, which are integral to Queensland's economy. In 1962, the first commercial production of oil in Queensland and Australia began at Moonie.

The humid climate—regulated by the availability of air conditioning—saw Queensland become a more accommodating place to work and live for Australian migrants.[32] To this day, it is one of Australia's economic powerhouses and the third-most populous state in the country.

21st century

In 2009, Queensland celebrated Q150, its 150th anniversary as an independent colony and state.[33] The Queensland government and other Queensland organisations commemorated the occasion with many events and publications, including the announcement of the top 150 icons of Queensland by the Queensland Premier Anna Bligh,[34][35] and the creation of monuments at significant survey points in Queensland's history to honour the many early explorer/surveyors who mapped the state.[36][37]

Geography

Queensland is an expansive area with a wide range of climates and geographical areas. If Queensland were an independent nation, it would be the 16th largest nation on earth. Most of Queensland's human population is on the East coast, particularly the southeast. Like much of eastern Australia, Queensland has a mountain range that runs roughly parallel with the coast, and areas west (inland) of this mountain range are much more arid than the coastal regions.

Queensland borders the Torres Strait to the north, with Boigu Island off the coast of New Guinea representing the absolute northern extreme of its territory. The triangular Cape York Peninsula, which points toward New Guinea, is the northernmost part of the state's mainland. West of the peninsula's tip, northern Queensland is bordered by the Gulf of Carpentaria, while the Coral Sea, an arm of the Pacific Ocean, borders Queensland to the east. To the west, Queensland is bordered by the Northern Territory, at the 138°E longitude, and to the southwest by the northeastern corner of South Australia.

In the south, there are three sections that constitute its border: the watershed from Point Danger to the Dumaresq River; the river section involving the Dumaresq, the Macintyre and the Barwon; and 29°S latitude (including some minor historical encroachments below the 29th parallel) over to the South Australian border.

The state capital is Brisbane, a coastal city 100 kilometres (60 mi) by road north of the New South Wales border. The state is divided into several officially recognised regions. Other smaller geographical regions of note include the Atherton Tablelands, the Granite Belt, and the Channel Country in the far southwest.

Queensland has many areas of natural beauty, including the Sunshine Coast and the Gold Coast, home to some of the state's most popular beaches; the Bunya Mountains and the Great Dividing Range, with numerous lookouts, waterfalls and picnic areas; Carnarvon Gorge; Whitsunday Islands; and Hinchinbrook Island. The state contains six World Heritage-listed preservation areas: Australian Fossil Mammal Sites at Riversleigh in the Gulf Country, Gondwana Rainforests of Australia, Fraser Island, Great Barrier Reef, Lamington National Park and the Wet Tropics of Queensland.

Mangrove swampland in Cape Tribulation

Mangrove swampland in Cape Tribulation Noosa Main Beach

Noosa Main Beach Mossman River during the wet season

Mossman River during the wet season Glasshouse Mountains

Glasshouse Mountains

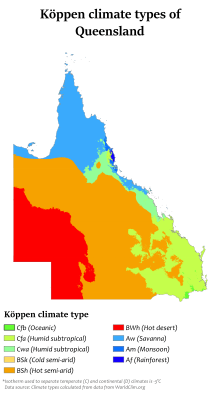

Climate

Because of its size, there is significant variation in climate across the state. Low rainfall and hot humid summers are typical for the inland and west, a monsoonal "wet" season in the far north, and warm, temperate conditions along the coastal strip. Elevated areas in the south-east inland can experience temperatures well below freezing in mid-winter providing frost and, albeit rarely, snowfall. The climate of the coastal strip is influenced by warm ocean waters, keeping the region free from extremes of temperature and providing moisture for rainfall.[38]

Natural disasters are often a threat in Queensland; severe tropical cyclones can impact the coast and cause severe damage,[39] with recent examples including Larry, Yasi, Ita and Debbie. Flooding from rain-bearing systems can also be severe and can occur anywhere in Queensland. One of the deadliest and most damaging floods in the history of the state occurred in early 2011.[40] Droughts and bushfires can also occur; however, the latter are generally less severe than those that occur in southern states. Severe springtime thunderstorms generally affect the south-east and inland of the state and can bring damaging winds, torrential rain, large hail and even tornadoes.[41] The strongest tornado ever recorded in Australia occurred in Queensland near Bundaberg.[42]

There are six predominant climatic zones in Queensland,[43] based on temperature and humidity:

- hot humid summer, warm humid winter (far north and coastal): Cairns, Innisfail

- hot humid summer, warm dry winter (north and coastal): Townsville, Mackay

- hot humid summer, mild dry winter (coastal elevated areas and coastal south-east): Brisbane, Bundaberg, Rockhampton

- hot dry summer, mild dry winter (central inland and north-west): Mt Isa, Emerald, Longreach

- hot dry summer, cool dry winter (southern inland): Roma, Charleville, Goondiwindi

- warm humid summer, cold dry winter (elevated south-eastern areas): Toowoomba, Warwick, Stanthorpe

However, most of the Queensland populace experience two weather seasons: a "winter" period of mild to warm temperatures and minimal rainfall, and a sultry summer period of hot, sticky temperatures and higher levels of rainfall.

The coastal far north of the state is the wettest place in Australia, with Mount Bellenden Ker, south of Cairns, holding many Australian rainfall records with its annual average rainfall of over 8 metres.[44] It is not uncommon for locations in this area to receive more rain in 24 hours during the wet season than the majority of Queensland receives in a year. Snow is rare in Queensland, although it does fall with some regularity along the far southern border with New South Wales, predominantly in the Stanthorpe district although on rare occasions further north and west. The most northerly snow ever recorded in Australia occurred near Mackay; however, this was exceptional.[45]

The annual mean statistics[46] for some Queensland centres are shown below:

| City | Min. temp | Max. temp | No. clear days | Rainfall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brisbane | 15.7 °C (60.3 °F) | 25.5 °C (77.9 °F) | 113.1 | 1,149.1 mm (45.24 in)[47] |

| Mackay | 19.0 °C (66.2 °F) | 26.4 °C (79.5 °F) | 123.0 | 1,570.7 mm (61.84 in)[48] |

| Cairns | 21.0 °C (69.8 °F) | 29.2 °C (84.6 °F) | 89.7 | 1,982.2 mm (78.04 in)[49] |

| Townsville | 19.8 °C (67.6 °F) | 28.9 °C (84.0 °F) | 120.9 | 1,136.7 mm (44.75 in)[50] |

The highest official maximum temperature recorded in the state was 49.5 °C (121.1 °F) at Birdsville Police Station on 24 December 1972,[51] although the Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Aqua satellite measured a ground surface temperature of 69.3 °C (156.7 °F). This temperature was the hottest value worldwide measured by MODIS in 2003.[52] Queensland has the highest average maximums of any Australian state, and Stanthorpe, Hervey Bay, Mackay, Atherton, Weipa and Thursday Island are the only large population centres not to have recorded a temperature above 40 °C (104 °F).

The lowest minimum temperature is −10.6 °C (12.9 °F) at Stanthorpe on 23 June 1961 and at The Hermitage (near Warwick) on 12 July 1965.[53] Temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) are, however, generally uncommon over the majority of populated Queensland.

| Climate data for Queensland | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 49.0 (120.2) |

47.2 (117.0) |

46.7 (116.1) |

41.7 (107.1) |

39.3 (102.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.5 (101.3) |

42.4 (108.3) |

45.1 (113.2) |

48.7 (119.7) |

49.5 (121.1) |

49.5 (121.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

| Source #1: Bureau of Meteorology[54] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Bureau of Meteorology[55] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Queensland is the second most decentralised of Australian states after Tasmania, with approximately 50% of the population living outside the state capital, and 25% living outside South East Queensland. Queensland is home to many regional cities, the most populous being the Gold Coast, the Sunshine Coast, Townsville, Cairns, Toowoomba, Mackay, Rockhampton and Bundaberg. For decades, Queensland has consistently been the fastest-growing state in Australia, although there have been periods where Victoria and Western Australia have grown faster.

Ancestry and immigration

| Country of Birth (2016)[59][60] | |

|---|---|

| Birthplace[N 2] | Population |

| Australia | 3,343,657 |

| New Zealand | 201,206 |

| England | 180,775 |

| India | 49,145 |

| Mainland China | 47,114 |

| South Africa | 40,131 |

| Philippines | 39,661 |

| Germany | 20,387 |

| Vietnam | 19,544 |

| South Korea | 18,327 |

| United States | 17,053 |

| Papua New Guinea | 16,120 |

| Taiwan | 15,592 |

At the 2016 census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[N 3][59][60]

- English (41.3%)

- Australian (37.9%)[N 4]

- Irish (13%)

- Scottish (11.2%)

- German (6.8%)

- Indigenous (4%)[N 5]

- Chinese (3.1%)

- Italian (3%)

- Indian (1.7%)

- Dutch (1.6%)

- New Zealander (1.6%)

- Maori (1.2%)

- Filipino (1.2%)

The 2016 census showed that 28.9% of Queensland's inhabitants were born overseas. Only 54.8% of inhabitants had both parents born in Australia, with the next most common birthplaces being New Zealand, England, India, Mainland China and South Africa.[59][60] Brisbane has the 26th largest immigrant population among world metropolitan areas.

4% of the population, or 186,482 people, identified as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) in 2016.[N 6][59][60]

Language

At the 2016 census, 81.2% of inhabitants spoke only English at home, with the next most common languages being Mandarin (1.5%), Vietnamese (0.6%), Cantonese (0.5%), Spanish (0.4%) and Italian (0.4%).[59][60]

Religion

At the 2016 census, the most commonly cited religious affiliations were 'No religion' (29.2%), Catholicism (21.7%) and Anglicanism (15.3%).[62]

Economy

In the 1870s to 1890s, sea ports were established on the coast, adjacent to the mouth of the Fitzroy River. Broadmount was on the northern side and Port Alma on the south. Railways were subsequently constructed to carry goods to the wharves at these locations, the railway to Broadmount opening on 1 January 1898 and the line to Port Alma opened on 16 October 1911. Maintenance on the Broadmount line ceased in August 1929. The following month, the wharf caught fire and the line was effectively closed in July 1930. The line to Port Alma closed on 15 October 1986.[63] Queensland's economy has enjoyed a boom in the tourism and mining industries over the past 20 years. A sizeable influx of interstate and overseas migrants, large amounts of federal government investment, increased mining of vast mineral deposits and an expanding aerospace sector have contributed to the state's economic growth.[64]

Between 1992 and 2002, the growth in the gross state product of Queensland outperformed that of all the other states and territories. In that period Queensland's GDP grew 5.0% each year, while growth in Australia's gross domestic product (GDP) rose on average 3.9% each year. Queensland's contribution to the Australian GDP increased by 10.4% in that period, one of only three states to do so.[65]

Primary industries include: bananas, pineapples, peanuts, a wide variety of other tropical and temperate fruit and vegetables, grain crops, wineries, cattle raising, cotton, sugarcane, wool and a mining industry including bauxite, coal, silver, lead, zinc, gold and copper. However, the Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tyroni), a pest native to Queensland, causes more than $28.5 million in damage to Australian fruit crops a year[66]. The damage is only expected to increase as global temperatures rise, as Queensland's hot humid climate is this pest's ideal habitat[67]. Secondary industries are mostly further processing of the above-mentioned primary produce. For example, bauxite is shipped by sea from Weipa and converted to alumina at Gladstone.[68] There is also copper refining and the refining of sugar cane to sugar at a number of mills along the eastern coastline. Major tertiary industries are the retail trade and tourism.

Interests in Crown land in Queensland are primarily regulated by the Land Act 1994.[69][70]

Tourism

Tourism is Queensland's leading tertiary industry with millions of interstate and overseas visitors flocking to the Sunshine State each year. The industry generates $8.8 billion annually, accounting for 4.5% of Queensland's Gross State Product. It has an annual export of $4.0 billion annually. The sector directly employs about 5.7% of Queensland citizens.[71]

Queensland is a state of many landscapes which range from sunny tropical coastal areas, lush rainforests to dry inland areas and temperate highland ranges. The main tourist destinations of Queensland[72][73][74] include, Brisbane, Cairns, Port Douglas and the Daintree Rainforest, Gold Coast, the Great Barrier Reef, Hervey Bay and nearby Fraser Island, Townsville, Magnetic Island, North Stradbroke Island and South Stradbroke Island, Sunshine Coast, Hamilton Island, Daydream Island and the Whitsundays known for Airlie Beach and Whitehaven Beach.

Cairns is renowned as the "Gateway to the Barrier Reef" and the heritage listed Daintree Rainforests. The Gold Coast of Queensland is also sometimes referred to as "Australia's Theme Park Capital", with five major amusement parks. These are Dreamworld, Movie World, Sea World, Wet 'n' Wild and WhiteWater World.

There are numerous wildlife parks in Queensland. On the Gold Coast there is Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary at Currumbin and David Fleay Wildlife Park at Burleigh Heads. On the Sunshine Coast there is UnderWater World at Mooloolaba and Australia Zoo near Beerwah/Glass House Mountains, home of Steve Irwin until his death in 2006.

Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary at Fig Tree Pocket and Brisbane Forest Park at The Gap are located in Brisbane. North of Brisbane is Alma Park Zoo which is relocating to Logan City and Kumbartcho Wildlife Sanctuary which was originally called Bunya Park Wildlife Sanctuary.

Accommodation in Queensland caters for nearly 22% of the total expenditure, followed by restaurants/meals (15%), airfares (11%), fuel (11%) and shopping/gifts (11%).[75]

Transport

Queensland is served by a number of National Highways and, particularly in South East Queensland, motorways such as the M1. The Department of Transport & Main Roads oversees the development and operation of main roads and public transport, including taxis and local aviation.

Principal rail services are provided by Queensland Rail and Pacific National, predominantly between the major towns along the coastal strip east of the Great Dividing Range.

Major seaports include the Port of Brisbane and subsidiary ports at Gladstone, Townsville and Bundaberg. There are large coal export facilities at Hay Point / Dalrymple Bay, Gladstone and Abbot Point. Sugar is another major export, with facilities at Lucinda and Mackay.

Brisbane Airport is the main international and domestic gateway serving the state. Gold Coast Airport, Cairns International Airport and Townsville Airport are the next most prominent airports, all with scheduled international flights. Other regional airports, with scheduled domestic flights, include Toowoomba Wellcamp Airport, Great Barrier Reef Airport, Hervey Bay Airport, Bundaberg Airport, Mackay Airport, Mount Isa Airport, Proserpine / Whitsunday Coast Airport, Rockhampton Airport, and Sunshine Coast Airport.

South East Queensland has an integrated public transport system operated by TransLink, which provides services bus, rail, light rail and ferry services through contracted bus, ferry and light rail operators and Queensland Rail. The TransLink network operates a fare system which allows a single ticket to be used across all modes for the same price irrespective of the number of transfers made on the trip. Regional bus and long-distance rail services are also provided throughout the State. Local bus services are also available in most regional centres.

As at 2017, the city of Gold Coast operates Queensland's only tram network.[76]

Governance

Executive authority is nominally vested in the Governor, who represents—and is formally appointed (on the advice of the Premier) by—Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia. The current governor is His Excellency, The Hon. Paul de Jersey, AC. The Head of government—the Premier—fulfills in reality the day-to-day functions of the state's executive, and is assisted in this by the Cabinet. He or she is appointed by the Governor but must have the support of the Legislative Assembly. The Premier is in practice a leading member of the Assembly and parliamentary leader of his or her political party, or coalition of parties. The current Premier is Annastacia Palaszczuk of the Labor Party. Other ministers, forming the Executive Council (which includes members of the Cabinet), are appointed by the Governor from among the notable members of the Legislative Assembly on the Premier's recommendation. They are in practice members of the Premier's party, or allied with it. A Speaker is elected by the Assembly to facilitate proceedings and communicate between the Assembly and the Governor, usually on matters relating to prorogation or dissolution of the Assembly.

(photo taken in 2003)

The Queensland Parliament or the Legislative Assembly, is unicameral. It is the only Australian state with a unicameral legislature. A bicameral system existed until 1922, when the Legislative Council was abolished by the Labor members' "suicide squad", so called because they were appointed for the purpose of voting to abolish their own offices.[77] The Parliament is housed in the 19th-century Parliament House and 20th-century Parliamentary Annexe in Brisbane. The state's politics are traditionally regarded as being conservative relative to other states.[78][79][80][81][82]

There are several factors that differentiate Queensland's government from other Australian states. The legislature has no upper house. For a large portion of its history, the state was under a gerrymander that heavily favoured rural electorates. This, combined with the already decentralised nature of Queensland, meant that politics has been dominated by regional interests. Queensland, along with New South Wales, formerly operated a balloting system known as optional preferential voting for state elections. This is different from the predominant Australian electoral system, the instant-runoff voting system, and in practice is closer to a first past the post ballot (similar to the ballot used in the UK), which some say is to the detriment of minor parties. The next Queensland election will use instant-runoff voting.

These conditions have had notable practical ramifications for politics in Queensland. The lack of an upper house for substantial legislative review has meant that Queensland has had a tradition of domination by strong-willed, populist premiers, often with arguably authoritarian tendencies, holding office for long periods.

The judicial system of Queensland consists of the Supreme Court and the District Court, established by the Constitution of Queensland, and various other courts and tribunals established by ordinary Acts of the Queensland Parliament.

In 2001 Queensland adopted a new codified constitution, repealing most of the assorted Acts of Parliament that had previously made up the constitution. The new constitution took effect on 6 June 2002, the anniversary of the formation of the colony of Queensland by the signing of Letters patent by Queen Victoria in 1859.

Local government

Local government is the mechanism by which towns and cities can manage their own affairs to the extent permitted by the Local Government Act 1993–2007. Queensland is divided into 77 local government areas which may be called Cities, Towns, Shires or Regions.[83]

Each area has a council which is responsible for providing a range of public services and utilities, and derives its income from both rates and charges on resident ratepayers, and grants and subsidies from the State and Commonwealth governments.[84]

Universities

The state's first university, the University of Queensland, was established in 1909. It was moved to St Lucia in 1945, where it remains today. The University of Queensland ranks amongst the top 60 universities in all major global rankings.

James Cook University was set up in 1970 to become the first tertiary education institution in North Queensland. Griffith University was established in the Brisbane suburb of Nathan in 1971. In 1989, the Queensland University of Technology was opened (previously the Queensland Institute of Technology) in the Brisbane central business district at Gardens Point. These Universities all have more than one campus, and all are recognised as leading Australian universities.

Bond University was established in 1989 as a private not-for-profit university, the first of its type in Queensland and Australia. It is located at Robina on the Gold Coast. In 1992, the Central Queensland University and University of Southern Queensland gained university status from previously operating and Institutes of Technologies, and the new University of the Sunshine Coast was established in 1994.

In 1997 the National Aboriginal Centre for the Performing Arts (ACPA) was established and in 2010 Southern Cross University opened a new campus at the southern part of the Gold Coast. The Australian Catholic University also operates a campus in Brisbane.

Sport

The state of Queensland is represented in all of Australia's national sporting competitions and is also host to a number of domestic and international sporting events. The most popular winter and summer team sports are Rugby league, Rugby union and cricket, respectively. Rugby league's annual State of Origin series is a major event in the Queensland sporting calendar, with the Queensland Maroons in 2013 winning a record eighth series in a row.

The Brisbane Broncos are the state's most successful team of any sport, having won three premierships in the NRL rugby league era and six in total during their 23-year existence. The Brisbane Broncos participated in the 2015 NRL Grand Final losing to the North Queensland Cowboys 17–16 in extra time, claiming their first premiership in its history. It is considered one of the greatest Grand Finals in NRL history. The other two NRL teams in Queensland are the North Queensland Cowboys and Gold Coast Titans.

Queensland's dominance is not restricted to rugby league. The early part of this century saw the AFL's Brisbane Lions claim a hat-trick of premierships between 2001 and 2003 inclusive, whilst in soccer, Brisbane Roar FC won back to back A-League titles in the 2010/11 and 2011/12 season, and also set an Australian sporting record of 36 consecutive games unbeaten. Just four years after being branded "the joke of rugby union", the Queensland Reds won its first Super Rugby title in July 2011. In netball the Queensland Firebirds went undefeated in the 2011 season as they went on to win the Grand Final. Other sports teams are the Brisbane Bullets and the Cairns Taipans, who compete in the National Basketball League.

Swimming is also a popular sport in Queensland, with a majority of Australian team members and international medalists hailing from the state. At the 2008 Summer Olympics, Queensland swimmers won all six of Australia's gold medals, all swimmers on Australia's three female (finals) relays teams were from Queensland, two of which won gold.

Events include:

- Gold Coast 600 (motorsport; since 1994)

- Gold Coast Marathon (athletics; since 1979)

- NRL All Stars Game (rugby league; since 2010)

- Townsville 400 (motorsport; since 2009)

- Quicksilver Pro and Roxy Pro (surfing)

- Australian PGA Championship (golf; since 2000)

See also

- Outline of Australia

- Index of Australia-related articles

- Queensland Day

Notes

- In the UK and US, /ˈkwiːnzlənd/ KWEENZ-lənd is the preferred variant.[5]

- Pre-1971 figures may not include the Indigenous population.

- In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, England, Scotland, Mainland China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau are listed separately

- As a percentage of 4,348,289 persons who nominated their ancestry at the 2016 census.

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the Anglo-Celtic group.[61]

- Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

- Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

References

- "Australian Demographic Statistics, Sep 2019". 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020. Estimated Resident Population – 30 September 2019

- "5220.0 – Australian National Accounts: State Accounts, 2018–19". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Floral Emblem of Queensland". Australian National Botanic Gardens. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Queensland". Parliament@Work. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3101.0Main%20Features3Sep%202019?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3101.0&issue=Sep%202019&num=&view=

- "How Old is Australia's Rock Art?". Aboriginal Art Online. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Dortch, C.E.; Hesp, P.A. (1994). "Rottnest Island artifacts and palaeosols in the context of Greater Swan Region prehistory". Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia. 77: 23–32.

- "Pomona – Quinalow". Place Names of South East Queensland. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Karl Bitar. "Labor History: Timeline: Foundations: Colonial Origins". Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- "Queensland's History". Qld.gov.au. 29 January 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "National Museum of Australia – Richard Daintree's glass plates". Archived from the original on 17 March 2011.

- A History of Queensland by Raymond Evans, Cambridge University Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-521-87692-6

- "European discovery and the colonisation of Australia". culture.gov.au. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Cumpston, JHL (1914). The History of Small-Pox in Australia 1788–1908. Melbourne: Australian Government Printer.

- Fenner, F.; Henderson, D.A.; Arita, I.; Jezek, Z. & Ladnyi, I.D. (1988). Smallpox and Its Eradication (History of International Public Health, No. 6) (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-156110-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Campbell, Judy; 2002, Invisible Invaders: Smallpox and Other Diseases in Aboriginal Australia 1780–1880, Carlton, Melbourne University Press, pp60–2, 80–1, 194–6, 201, 216–7

- Willis, H.A. (2011). "Bringing Smallpox with the First Fleet". Quadrant. 55 (7–8): 2. ISSN 0033-5002.

- "New Hope Group". Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- "Extermination of the Queenslands Blacks". Empire (5246). New South Wales, Australia. 12 September 1868. p. 3. Retrieved 12 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Welcome to Frontier". Abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- Australia. "Stories of the Dreaming – Australian Museum". Dreamtime.net.au. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- NSWV&P re 26 October 1857

- MBC 14 November 1857

- Book: Reid, Gordon: A Nest of Hornets: The Massacre of the Fraser family at Hornet Bank Station, Central Queensland, 1857, and related events, Melbourne 1982.

- "The Massacre by the Blacks at Nogoa". The Maitland Mercury And Hunter River General Advertiser. XVIII (2106). New South Wales, Australia. 19 November 1861. p. 2. Retrieved 12 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- R Evans, quoted in T Bottoms (2013) Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland's frontier killing times, Allen & Unwin, p.181

- "Q150 Timeline". Queensland Treasury. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- Rickard, John (2017). Australia: A Cultural History. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-921867-60-6.

- "Documenting Democracy". Foundingdocs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages World War One commemorative death certificates | Queensland's World War 1 Centenary". blogs.slq.qld.gov.au. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Lowe, Ian (2012). Bigger Or Better?: Australia's Population Debate. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 9780702248078.

- "Queensland turns 150 in 2009". Q150. Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 15 December 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Bligh, Anna (10 June 2009). "Premier unveils Queensland's 150 icons". Media Statements. Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- "Q150 icons list". Brisbane Times. 10 June 2009. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Robertson, Stephen (24 June 2009). "Q150 honours Queensland's earliest explorers". Media statements. Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- "About SSSI Q150 Project". Surveying and Spatial Sciences Institute Q150. Surveying and Spatial Sciences Institute. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- National Climate Centre. "Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology – Climate of Queensland". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "Queensland Cyclones". Emergency Management Queensland. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Queensland Floods Summary". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Queensland Severe Storms". Emergency Management Queensland. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Tornadoes". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- "Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology – Australian climatic zones". Bom.gov.au. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "Rainfall and Temperature Records". Climate Extremes. Bureau of Meteorology. 28 February 2013. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- "Queensland Snow Events". Weather Armidale. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology – Climate statistics for Australian locations". Bureau of Meteorology. 19 July 2010. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "Brisbane Regional Office". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Mackay M.O." Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Cairns Aero". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Townsville Aero". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Rainfall and Temperature Records". Bureau of Meteorology (Australian Government). Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- "The Hottest Spot on Earth". NASA. 24 November 2006. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Rainfall and Temperature Records: National" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- "Official records for Queensland in February". Daily Extremes. Bureau of Meteorology. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Official records for Queensland in October". Daily Extremes. Bureau of Meteorology. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- "Historical tables, demography, 1823 to 2008 (Q150 release)". Queensland Government Statistician's Office. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Australian Bureau of Statistics https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Previousproducts/3101.0Main%20Features1Jun%202016?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3101.0&issue=Jun%202016&num=&view=. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Australian Bureau of Statistics https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/communityprofile/3?opendocument. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Australian Bureau of Statistics http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/CensusOutput/copsub2016.NSF/All%20docs%20by%20catNo/2016~Community%20Profile~3/$File/GCP_3.zip?OpenElement. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Feature Article - Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Australia (Feature Article)". Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- "Media Release - 2016 Census: Queensland". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 June 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Kerr, John (August 2001). "The Port Railways of Rockhampton". Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin. pp. 283–306.

- Tom Dusevic (17 December 2009). "Queensland falls back with the pack". The Australian. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- "1387.3 – Queensland in Review, 2003". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 November 2003. Archived from the original on 26 December 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- Lloyd, Annice C.; Hamacek, Edward L.; Kopittke, Rosemary A.; Peek, Thelma; Wyatt, Pauline M.; Neale, Christine J.; Eelkema, Marianne; Gu, Hainan (1 May 2010). "Area-wide management of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Central Burnett district of Queensland, Australia". Crop Protection. 29 (5): 462–469. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2009.11.003. ISSN 0261-2194.

- Bateman, MA (1967). "Adaptations to temperature in geographic races of the Queensland fruit fly Dacus (Strumenta) tryoni". Australian Journal of Zoology. 15 (6): 1141. doi:10.1071/zo9671141. ISSN 0004-959X.

- "Gladstone". Comalco.com. Rio Tinto Aluminium. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- Cradduck, Lucy; Blake, Andrea (2010). "Dealing with unique interests in Crown Land: A Queensland perspective" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Land Act 1994, Long title An Act to consolidate and amend the law relating to the administration and management of non-freehold land and deeds of grant in trust and the creation of freehold land, and for related purposes "Land Act 1994 – Long Title". Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- "About TQ – Profile". Tourism Queensland. Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- "The Great Barrier Reef and beyond: a beginner's guide to Queensland's coast". Lonely Planet. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Kristof Haines (19 August 2015). "Earth's Top Travel Destinations Revealed". Writer for AirportRentals.com. AirportRentals.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- TravelTreks (8 September 2016). "Australia's Top 50 Small Towns". www.DiscountMyFlights.com.au. Stapylton, Queensland, Australia. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Tourism related information and statistics". Discoverqueensland.com.au. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "Sharing the road with trams | Transport and motoring". Department of Transport and Main Roads. Queensland Government. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Wanna, John (2003). "Queensland". In Moon, Campbell; Sharman, Jeremy (eds.). Australian Politics and Government: The Commonwealth, the States and Territories. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-82507-8. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- Daly, Margo (2003). The Rough Guide To Australia. Rough Guides Ltd. p. 397. ISBN 978-1-84353-090-9.

- Penrith, Deborah (2008). Live & Work in Australia. Crimson Publishing. p. 478. ISBN 978-1-85458-418-2.

- "Why Labor struggles in Queensland". 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013.

- George Megalogenis, "The Green and the Grey", Quarterly Essay, Vol. 40, 2010, p69.

- "Australia ready for first female leader". BBC News. 25 June 2010. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012.

- Local Government Act 1993 Archived 23 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, s.34. (Reprint 11E, as in force at 22 November 2007.)

- "Rates and valuations". Queensland: Department of Local Government, Sport and Recreation. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 19 March 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Queensland. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Queensland. |

- Government of Queensland

- State Archives, Government of Queensland

- State Library, Government of Queensland

- Far North Queensland (historical footage), AU: National Film and Sound Archive, 21 August 2012.

- Daintrees, Richard, Glass plates, AU: National Museum.

- Works by Queensland at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Queensland at Internet Archive