West Indies

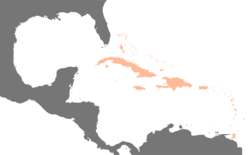

The West Indies is a region of the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean that includes the island countries and surrounding waters of three major archipelagos: the Greater Antilles, the Lesser Antilles, and the Lucayan Archipelago.[1]

The region includes all the islands in or bordering the Caribbean Sea, plus The Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands, which are in the Atlantic Ocean. This term also includes modern-day Belize, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.

History

Indigenous people were the very first inhabitants of the West Indies. In 1492, Christopher Columbus became the first European to arrive at the islands, where he is believed by historians to have first set foot on land in the Bahamas. After the first of the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the Americas, Europeans began to use the term West Indies to distinguish the region from the East Indies of South Asia and Southeast Asia.

In the late sixteenth century, French, English and Dutch merchants and privateers began their operations in the Caribbean Sea, attacking Spanish and Portuguese shipping and coastal areas. They often took refuge and refitted their ships in the areas the Spanish could not conquer, including the islands of the Lesser Antilles, the northern coast of South America including the mouth of the Orinoco, and the Atlantic Coast of Central America. In the Lesser Antilles they managed to establish a foothold following the colonisation of St Kitts in 1624 and Barbados in 1626, and when the Sugar Revolution took off in the mid-seventeenth century, they brought in thousands of Africans to work the fields and mills as slave labourers. These Africans wrought a demographic revolution, replacing or joining with either the indigenous Caribs or the European settlers who were there as indentured servants.

The struggle between the northern Europeans and the Spanish spread southward in the mid to late seventeenth century, as English, Dutch, French and Spanish colonists, and in many cases their slaves from Africa first entered and then occupied the coast of The Guianas (which fell to the French, English and Dutch) and the Orinoco valley, which fell to the Spanish. The Dutch, allied with the Caribs of the Orinoco, would eventually carry the struggles deep into South America, first along the Orinoco and then along the northern reaches of the Amazon.

Since no European country had occupied much of Central America, gradually the English of Jamaica established alliances with the Miskito Kingdom of modern-day Nicaragua and Honduras, and then began logging on the coast of modern-day Belize. These interconnected commercial and diplomatic relations made up the Western Caribbean Zone which was in place in the early eighteenth century. In the Miskito Kingdom, the rise to power of the Miskito-Zambos, who originated in the survivors of a rebellion aboard a slave ship in the 1640s and the introduction of African slaves by British settlers within the Miskito area and in Belize, also transformed this area into one with a high percentage of persons of African descent as was found in most of the rest of the Caribbean.

From the 17th through the 19th century, the European colonial territories of the West Indies were the French West Indies, British West Indies, the Danish West Indies, the Netherlands Antilles (Dutch West Indies), and the Spanish West Indies.

In 1916, Denmark sold the Danish West Indies to the United States[2] for US$25 million in gold, per the Treaty of the Danish West Indies. The Danish West Indies became an insular area of the U.S., called the United States Virgin Islands.

Between 1958 and 1962, the United Kingdom re-organised all their West Indies island territories (except the British Virgin Islands and the Bahamas) into the West Indies Federation. They hoped that the Federation would coalesce into a single, independent nation. However, the Federation had limited powers, numerous practical problems, and a lack of popular support; consequently, it was dissolved by the British in 1963, with nine provinces eventually becoming independent sovereign states and four becoming current British Overseas Territories.

West Indies or West India was the namesake of several companies of the 17th and 18th centuries, including the Danish West India Company, the Dutch West India Company, the French West India Company, and the Swedish West India Company.[3]

West Indian is the official term used by the U.S. government to refer to people of the West Indies.[4]

Use of the term

Tulane University professor Rosanne Adderly says:

[T]he phrase "West Indies" distinguished the territories encountered by Columbus or and claimed by Spain from discovery claims by other powers in [Asia's] "East Indies"... The term "West Indies" was eventually used by all European nations to describe their own acquired territories in the Americas... considering British Caribbean colonies collectively as the "West Indies" had its greatest political importance in the 1950s with the movement to create a federation of those colonies that could ultimately become an independent nation... Despite the collapse of the Federation [in the early 1960s]... the West Indies continues to field a joint cricket team for international competition.[5]

The West Indies cricket team includes participants from Guyana, which is geographically located in South America.

Geology

The West Indies is a geologically complex island system consisting of 7,000 islands and islets stretching over 3,000 km from the Florida peninsula of North America south-southeast to the northern coast of Venezuela.[6] These islands include active volcanoes, low-lying atolls, raised limestone islands, and large fragments of continental crust containing tall mountains and insular rivers.[7] Each of the three archipelagos of the West Indies has a unique origin and geologic composition.

Greater Antilles

The Greater Antilles is geologically the oldest of the three archipelagos and includes both the largest islands (Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico) and the tallest mountains (Pico Duarte, Blue Mountain, Pic la Selle, Pico Turquino) in the Caribbean.[8] The islands of the Greater Antilles are composed of strata of different geological ages including Precambrian fragmented remains of the North American Plate (older than 541 million years), Jurassic aged limestone (201.3-145 million years ago), as well as island arc deposits and oceanic crust from the Cretaceous (145-66 million years ago).[9]

The Greater Antilles originated near the Isthmian region of present day Central America in the Late Cretaceous (commonly referred to as the Proto-Antilles), then drifted eastward arriving in their current location when colliding with the Bahama Platform of the North American Plate ca. 56 million years ago in the late Paleocene.[10] This collision caused subduction and volcanism in the Proto-Antillean area and likely resulted in continental uplift of the Bahama Platform and changes in sea level.[11] The Greater Antilles have continuously been exposed since the start of the Paleocene or at least since the Middle Eocene (66-40 million years ago), but which areas were above sea level throughout the history of the islands remains unresolved.[12][10]

The oldest rocks in the Greater Antilles are located in Cuba. They consist of metamorphosed graywacke, argillite, tuff, mafic igneous extrusive flows, and carbonate rock.[13] It is estimated that nearly 70% of Cuba consists of karst limestone.[14] The Blue Mountains of Jamaica are a granite outcrop rising over 2,000 meters, while the rest of the island to the west consists mainly of karst limestone.[14] Much of Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands were formed by the collision of the Caribbean Plate with the North American Plate and consist of 12 island arch terranes.[15] These terranes consist of oceanic crust, volcanic and plutonic rock.[15]

Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles is a volcanic island arc rising along the leading edge of the Caribbean Plate due to the subduction of the Atlantic seafloor of the North American and South American plates. Major islands of the Lesser Antilles likely emerged less than 20 Ma, during the Miocene.[8] The volcanic activity that formed these islands began in the Paleogene, after a period of volcanism in the Greater Antilles ended, and continues today.[16] The main arc of the Lesser Antilles runs north from the coast of Venezuela to the Anegada Passage, a strait separating them from the Greater Antilles, and includes 19 active volcanoes.[17]

Lucayan Archipelago

The Lucayan Archipelago includes the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands, a chain of barrier reefs and low islands atop the Bahama Platform. The Bahama Platform is a carbonate block formed of marine sediments and fixed to the North American Plate.[7] The emergent islands of the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos likely formed from accumulated deposits of wind-blown sediments during Pleistocene glacial periods of lower sea level.[7]

Countries and territories by subregion and archipelago

Caribbean

Antilles

Greater Antilles

Hispaniola

Lesser Antilles

Leeward Islands

SSS Islands

Virgin Islands

Windward Islands

Lucayan Archipelago

Central America

Northern America

South America

N.B. Territories in italics are parts of transregional sovereign states or non-sovereign dependencies.

# These three Dutch Caribbean territories form the BES Islands.

† Physiographically, these are continental islands not part of the volcanic Windward Islands arc, with which these are grouped culturally and politically.

* Physiographically a North Atlantic oceanic island, not part of the Caribbean, West Indies, North American continent or South American continent. Usually grouped with Northern American countries based on proximity; sometimes grouped with the West Indies culturally.

See also

- Caribbean Basin Initiative

- Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act

- Caribbean Community

- History of the Caribbean

- History of the British West Indies

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- West Indian

- North America

References

- Caldecott, Alfred (1898). The Church in the West Indies. London: Frank Cass and Co. p. 11. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- "Two telegrams about the sale – The Danish West-Indies". The Danish West-Indies. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- Garrison, William L.; Levinson, David M. (2014). The Transportation Experience: Policy, Planning, and Deployment. OUP USA. ISBN 9780199862719.

- "Info Please U.S. Social Statistics". Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- Rosanne Adderly, "West Indies", in Encyclopedia of Contemporary Latin American and Caribbean Cultures, Volume 1: A-D (London and New York: Routledge, 2000): 1584.

- "West Indies | History, Maps, Facts, & Geography". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- Ricklefs Robert; Bermingham Eldredge (2008-07-27). "The West Indies as a laboratory of biogeography and evolution". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1502): 2393–2413. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2068. PMC 2606802. PMID 17446164.

- Biogeography of the West Indies : patterns and perspectives. Woods, Charles A. (Charles Arthur), Sergile, Florence E. (Florence Etienne), 1954– (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0849320019. OCLC 46240352.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Flora of the West Indies / Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution". naturalhistory2.si.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- Graham, Alan (2003). "Geohistory Models and Cenozoic Paleoenvironments of the Caribbean Region". Systematic Botany. 28 (2): 378–386. ISSN 0363-6445. JSTOR 3094007.

- Santiago–Valentin, Eugenio; Olmstead, Richard G. (2004). "Historical biogeography of Caribbean plants: introduction to current knowledge and possibilities from a phylogenetic perspective". Taxon. 53 (2): 299–319. doi:10.2307/4135610. ISSN 1996-8175. JSTOR 4135610.

- Iturralde-Vinent, Manuel A. (2006-09-01). "Meso-Cenozoic Caribbean Paleogeography: Implications for the Historical Biogeography of the Region". International Geology Review. 48 (9): 791–827. Bibcode:2006IGRv...48..791I. doi:10.2747/0020-6814.48.9.791. ISSN 0020-6814.

- Khudoley, K. M.; Meyerhoff, A. A. (1971), "Paleogeography and Geological History of Greater Antilles", Geological Society of America Memoirs, Geological Society of America, pp. 1–192, doi:10.1130/mem129-p1, ISBN 978-0813711294

- geolounge (2012-01-08). "Caribbean Islands: the Greater Antilles". GeoLounge: All Things Geography. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- Mann, Paul; Draper, Grenville; Lewis, John F. (1991), "An overview of the geologic and tectonic development of Hispaniola", Geological Society of America Special Papers, Geological Society of America, pp. 1–28, doi:10.1130/spe262-p1, ISBN 978-0813722627

- Santiago-Valentin, Eugenio; Olmstead, Richard G. (2004). "Historical Biogeography of Caribbean Plants: Introduction to Current Knowledge and Possibilities from a Phylogenetic Perspective". Taxon. 53 (2): 299–319. doi:10.2307/4135610. ISSN 0040-0262. JSTOR 4135610.

- "The University of the West Indies Seismic Research Centre". uwiseismic.com. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Indies. |

- Cromwell, Jesse. "More than Slaves and Sugar: Recent Historiography of the Trans-imperial Caribbean and Its Sinew Populations." History Compass (2014) 12#10 pp 770–783.

- Higman, Barry W. A Concise History of the Caribbean. (2011)

- Jones, Alfred Lewis (1905). . The Empire and the century. London: John Murray. pp. 877–882.

- Martin, Tony, Caribbean History: From Pre-colonial Origins to the Present (2011)