Bengalis

Bengalis (Bengali: বাঙালি [baŋali]), also rendered as the Bengali people,[32] are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group native to the Bengal region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, presently divided between Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Assam's Barak Valley. They speak Bengali, a language from the Indo-Aryan language family. The term "Bangalee" is also used to denote people of Bangladesh as a nation.[33]

বাঙালি | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 228–243 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,000,000[5][6][7][8] | |

| 1,309,004[9] | |

| 1,089,917[10] | |

| 451,000[11] | |

| 280,000[12] | |

| 257,740[13][14][lower-alpha 1] | |

| 221,000[15] | |

| 200,000[16] | |

| 135,000[17] | |

| 100,000[18] | |

| 97,115[19] | |

| 69,420[20] | |

| 54,566[21] | |

| 26,582[22] | |

| 13,600[23] | |

| 12,374[24] | |

| 8,000[25] | |

| Languages | |

| Bengali | |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan peoples | |

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Bengali history

|

|

Bengali homeland

|

|

|

Bengali symbols

|

|

Politics

|

Bengalis are the third largest ethnic group in the world, after Han Chinese and Arabs.[34] Apart from Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam's Barak Valley, Bengali-majority populations also reside in India's union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands as well as Bangladesh's Chittagong Hill Tracts, with significant populations in Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Uttarakhand.[35] The global Bengali diaspora (Bangladeshi diaspora and Indian Bengalis) have well-established communities in Pakistan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, the Middle East, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, and Italy.

They have four major religious subgroups: Bengali Muslims, Bengali Hindus, Bengali Christians, and Bengali Buddhists.

Name

In modern usage, "Bengali" or "Bangali" is used to refer to anyone whose linguistic, cultural, family ancestral or genetic origins are from Bengal. Their ethnonym is derived from the ancient Banga or Bangla. The exact origin of the word Bangla is unknown, though it is believed to come from "Bung", a son of Hind.[36][37] According to the Mahabharata, the Puranas and the Harivamsha, Vanga was one of the adopted sons of King Vali who founded the Vanga Kingdom. It was either under Magadh or under Kalinga Rules except few years under Pals. The earliest reference to "Vangala" (Bôngal) has been traced in the Nesari plates (805 CE) of Rashtrakuta Govinda III which speak of Dharmapala as the king of Vangala. The records of Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty, who invaded Bengal in the 11th century, speak of Govindachandra as the ruler of Vangaladesa.[38][39] Shams-ud-din Ilyas Shah took the title "Shah-e-Bangla" and united the whole region under one government.

An interesting theory of the origin of the name is provided by Abu'l-Fazl in his Ain-i-Akbari. According to him, "The original name of Bengal was Bung, and the suffix "al" came to be added to it from the fact that the ancient rajahs of this land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al". From this suffix added to the Bung, the name Bengal arose and gained currency".[40] This is also mentioned in Ghulam Husain Salim's Riyaz-us-Salatin.[41]

History

Ancient history

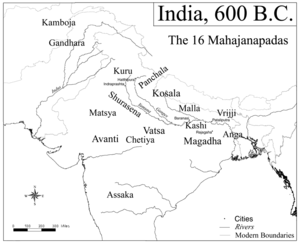

Anga in 600 BCE.

Anga in 600 BCE.- Magadha from 6th–4th centuries BCE.

.png) Anga, Pundra, Vanga, Radha in 500 BCE.

Anga, Pundra, Vanga, Radha in 500 BCE. Gangaridai in 323 BCE.

Gangaridai in 323 BCE.

Archaeologists have discovered remnants of a 4,000-year-old Chalcolithic civilisation in the greater Bengal region, and believe the finds are one of the earliest signs of settlement in the region.[42] However, evidence of much older Palaeolithic human habitations were found in the form of a stone implement and a hand axe in Rangamati and Feni districts of Bangladesh.[43] The origin of the word Bangla ~ Bengal is unknown, though it is believed to be derived from a tribe called Bang that settled in the area around the year 1000 BCE.[36]

Kingdoms of Pundra and Vanga were formed in Bengal and were first described in the Atharvaveda around 1000 BCE as well as in Hindu epic Mahabharata. Anga and later Magadha expanded to include most of the Bihar and Bengal regions. It was one of the four main kingdoms of India at the time of Buddha and was one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas. Under the Maurya Empire founded by Chandragupta Maurya, Magadha extended over nearly all of South Asia, including parts of Balochistan and Afghanistan, reaching its greatest extent under the Buddhist emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BCE.

One of the earliest foreign references to Bengal is the mention of a land ruled by the king Xandrammes named Gangaridai by the Greeks around 100 BCE. The word is speculated to have come from Gangahrd ('Land with the Ganges in its heart') in reference to an area in Bengal.[44] Later from the 3rd to the 6th centuries CE, the kingdom of Magadha served as the seat of the Gupta Empire.

Middle Ages

The Pala Empire circa 800 CE.

The Pala Empire circa 800 CE. Art of the Sena Empire, 11th century.

Art of the Sena Empire, 11th century.- Dakhil Darwaza, the Gateway of Lakhnauti.

One of the first recorded independent kings of Bengal was Shashanka, reigning around the early 7th century.[45] After a period of anarchy, Gopala came to power in 750. He founded the Bengali Buddhist Pala Empire which ruled the region for four hundred years, and expanded across much of Southern Asia: from Assam in the northeast, to Kabul in the west, and to Andhra Pradesh in the south.[46] Atisha was a renowned Bengali Buddhist teacher who was instrumental in the revival of Buddhism in Tibet and also held the position of Abbot at the Vikramshila university. Tilopa was also from the Bengal region.

The Pala Empire enjoyed relations with the Srivijaya Empire, the Tibetan Empire, and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. Islam first appeared in Bengal during Pala rule, as a result of increased trade between Bengal and the Middle East.[47]

The Pala dynasty was later followed by a shorter reign of the Hindu Sena Empire. Islam was introduced to Bengal in the twelfth century by Sufi missionaries. Subsequent Muslim conquests helped spread Islam throughout the region.[48] Bakhtiar Khalji, a Turkic general of the Slave dynasty of Delhi Sultanate, defeated Lakshman Sen of the Sena dynasty and conquered large parts of Bengal. Consequently, the region was ruled by dynasties of sultans and feudal lords under the Bengal Sultanate for the next few hundred years. Islam was introduced to the Sylhet region by the Muslim saint Shah Jalal in the early 14th century.

Mughal era

The Mughal Empire conquered Bengal in the 16th century. Mughal general Man Singh conquered parts of Bengal including Dhaka during the time of Emperor Akbar. A few Rajput tribes from his army permanently settled around Dhaka and surrounding lands. Later, in the early 17th century, Islam Khan conquered all of Bengal. However, administration by governors appointed by the court of the Mughal Empire gave way to semi-independence of the area under the Nawabs of Murshidabad, who nominally respected the sovereignty of the Mughals in Delhi.

The Bengal Subah province in the Mughal Empire was the wealthiest state in the subcontinent. Bengal's trade and wealth impressed the Mughals so much that it was described as the Paradise of the Nations by the Mughal Emperors.[49]

Under Mughal rule, Bengal was a center of the worldwide muslin and silk trades. During the Mughal era, the most important center of cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[50] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.[51] From Bengal, saltpetre was also shipped to Europe, opium was sold in Indonesia, raw silk was exported to Japan and the Netherlands, cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia, and Japan,[52] cotton cloth was exported to the Americas and the Indian Ocean.[53] Bengal also had a large shipbuilding industry. Economic historian Indrajit Ray estimates shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[54]

After the weakening of the Mughal Empire with the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, Bengal was ruled independently by the Nawabs until 1757, when the region was annexed by the East India Company after the Battle of Plassey.

British colonisation

In Bengal effective political and military power was transferred from the old regime to the British East India Company around 1757–65.[55] Company rule in India began under the Bengal Presidency. Calcutta was named the capital of British India in 1772. The presidency was run by a military-civil administration, including the Bengal Army, and had the world's sixth earliest railway network. Great Bengal famines struck several times during colonial rule, notably the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and Bengal famine of 1943, each killing millions of Bengalis.

Under British rule, Bengal experienced deindustrialisation.[56] The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was initiated on the outskirts of Calcutta, and spread to Dhaka, Chittagong, Jalpaiguri, Sylhet and Agartala, in solidarity with revolts in North India. The failure of the rebellion led to the abolishment of the Mughal Court and direct rule by the British Raj.

Bengal renaissance

Bengal renaissance refers to a socio-religious reform movement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, centered around the city of Calcutta and predominantly led by upper caste Bengali Hindus under the patronage of the British Raj who created a reformed religion called Brahmo dharma. Historian Nitish Sengupta describes the Bengal renaissance as having started with reformer and humanitarian Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833), considered the "Father of the Bengal renaissance", and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).[57]

Other figures have been considered to be part of the renaissance. Swami Vivekananda is considered a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and America[58] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, and bringing Hinduism to the status of a world religion during the 1800s.[59] Jagadish Chandra Bose was a Bengali polymath: a physicist, biologist, botanist, archaeologist, and writer of science fiction[60] who pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[61] He is considered one of the fathers of radio science,[62] and is also considered the father of Bengali science fiction. Satyendra Nath Bose was a Bengali physicist, specialising in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate. He is honoured as the namesake of the boson.

According to Nitish Sengupta, though the Bengal renaissance was the "culmination of the process of emergence of the cultural characteristics of the Bengali people that had started in the age of Hussein Shah, it remained predominantly Hindu and only partially Muslim."[63] There were, nevertheless, examples of Muslim intellectuals such as Syed Ameer Ali, Mosharraf Hussain,[63] Sake Dean Mahomed, Kazi Nazrul Islam, and Roquia Sakhawat Hussain. The Freedom of Intellect Movement sought to challenge religious and social dogma in Bengali Muslim society.

Independence movement

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar were dominant. Many of the early proponents of the independence struggle, and subsequent leaders in the movement were Bengalis such as Chittaranjan Das, Khwaja Salimullah, Surendranath Banerjea, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Titumir (Sayyid Mir Nisar Ali), Prafulla Chaki, A. K. Fazlul Huq, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, Bagha Jatin, Khudiram Bose, Surya Sen, Binoy-Badal-Dinesh, Sarojini Naidu, Aurobindo Ghosh, Rashbehari Bose, and Sachindranath Sanyal.

Some of these leaders, such as Netaji, who was born, raised and educated at Cuttack in Odisha did not subscribe to the view that non-violent civil disobedience was the best way to achieve Indian Independence, and were instrumental in armed resistance against the British force. Netaji was the co-founder and leader of the Japanese-aligned Indian National Army (distinct from the army of British India) that challenged British forces in several parts of India. He was also the head of state of a parallel regime, the Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind. Bengal was also the fostering ground for several prominent revolutionary organisations, the most notable of which was Anushilan Samiti. A number of Bengalis died during the independence movement and many were imprisoned in Cellular Jail, the notorious prison in Andaman.

Partitions of Bengal

The first partition in 1905 divided the Bengal region in British India into two provinces for administrative and development purposes. However, the partition stoked Hindu nationalism. This in turn led to the formation of the All India Muslim League in Dhaka in 1906 to represent the growing aspirations of the Muslim population. The partition was annulled in 1912 after protests by the Indian National Congress and Hindu Mahasabha.

The breakdown of Hindu-Muslim unity in India drove the Muslim League to adopt the Lahore Resolution in 1943, calling the creation of "independent states" in eastern and northwestern British India. The resolution paved the way for the Partition of British India based on the Radcliffe Line in 1947, despite attempts to form a United Bengal state that was opposed by many people.

The legacy of partition has left lasting differences between the two sides of Bengal, most notably in linguistic accent and cuisine.

Bangladesh Liberation War

The rise of self-determination and Bengali nationalism movements in East Bengal, led by Mujibur Rahman, culminated in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War against the Pakistani military junta. An estimated 3 million (3,000,000) people died in the conflict, particularly as a result of the 1971 Bangladesh genocide. The war caused millions of East Pakistani refugees to take shelter in India's Bengali state West Bengal, with Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal province, becoming the capital-in-exile of the Provisional Government of Bangladesh. The Mukti Bahini guerrilla forces waged a nine-month war against the Pakistani military. The conflict ended after the Indian Armed Forces intervened on the side of Bangladeshi forces in the final two weeks of the war, which ended with the Surrender of Pakistan and the liberation of Dhaka on 16 December 1971.

Culture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History |

|

|

|

Traditions

|

|

Mythology and folklore Myths

Lores

|

| Cuisine |

|

Festivals

|

|

Art

|

|

Literature History

Genres

Institutions

Awards

|

|

Music and performing arts

Folk genres

Devotional

Classical genres

Modern genres

People

Instruments

Dance

Theater

Organizations

People

|

|

Media

|

|

|

Cuisine

Bengali cuisine is the culinary style originating in Bengal, a region of the Indian subcontinent which is now located in Bangladesh and West Bengal. Some Indian regions like Tripura, Shillong and the Barak Valley region of Assam (in India) also have large native Bengali populations and share this cuisine. With an emphasis on fish, vegetables, and milk served with rice as a staple diet, Bengali cuisine is known for its subtle flavours, and its huge spread of confectioneries and desserts. It also has the only traditionally developed multi-course tradition from the Indian subcontinent that is analogous in structure to the modern service à la russe style of French cuisine, with food served course-wise rather than all at once.

Festivals

Bengalis celebrate the major holidays of the Hindu and Muslims faiths. Although Bengali Hindus observe Holi, Diwali, and other important religious festivals, Durga Puja is the biggest and most important to them. Dedicated to the goddess Durga, who is a manifestation of Shakti, the festivities last for five days. Months before the festival, special clay idols of Durga and her children are made. These show her mounted on a lion and killing the evil demon Mahishasura. These lavishly painted and decorated idols are displayed and worshipped on each day of the festival in the pandals and at homes. On the tenth day, the idols are decorated with flowers and carried through the streets in processions. The procession makes its way to a river or other body of water, where the image of Durga is immersed in the water. For Muslims, the festivals include Eid-ul-Azha, Eid-ul-Fitr, and Muharram.

Language

Bengali or Bangla is the language native to the region of Bengal, which comprises present-day Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and southern Assam. It is written using the Bengali script. With about 250 million native and about 300 million total speakers worldwide, Bengali is one of the most spoken languages, ranked seventh in the world.[64][65] The National Anthem of Bangladesh, National Anthem of India and the National Song of India were first composed in the Bengali language.

Along with other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, Bengali evolved circa 1000–1200 CE from eastern Middle Indo-Aryan dialects such as the Magadhi Prakrit and Pali, which developed from a dialect or group of dialects that were close, but not identical to, Vedic and Classical Sanskrit.

Bengali people may be broadly classified into sub-groups predominantly based on language but also other aspects of culture:

- Bangals: This is a term used predominantly in Indian West Bengal to refer to East Bengalis – i.e. Bangladeshis as well as those whose ancestors originate from Eastern Bengal. The East Bengali dialects are known as Bangali. This group constitutes the majority of ethnic Bengalis.

- Ghotis: This is the term favoured by the natives of West Bengal to distinguish themselves from other Bengalis.

- Sylhetis: They speak Sylheti and are native to the Sylhet region of Bangladesh and India. They maintain a distinct identity separate from or in addition to having a Bengali identity.[66][67]

- Chittagonians: Natives of the Chittagong region of Bangladesh. They speak in the Chittagonian language, locally called 'Chatgaiya', and follow a distinct culture.

Literature

The earliest extant work in Bengali literature is the Charyapada, a collection of Buddhist mystic songs dating back to the 10th and 11th centuries. Thereafter, the timeline of Bengali literature is divided into two periods: medieval (1360–1800) and modern (1800–present). Bengali literature is one of the most enriched bodies of literature in Modern India and Bangladesh.

The first works in Bengali, written in new Bengali, appeared between 10th and 12th centuries CE It is generally known as the Charyapada. These are mystic songs composed by various Buddhist seer-poets: Luipada, Kanhapada, Kukkuripada, Chatilpada, Bhusukupada, Kamlipada, Dhendhanpada, Shantipada, Shabarapada, etc. The famous Bengali linguist Haraprasad Shastri discovered the palm-leaf Charyapada manuscript in the Nepal Royal Court Library in 1907.

The Middle Bengali Literature is a period in the history of Bengali literature dating from 15th to 18th centuries. Following the Mughal invasion of Bengal in the 13th century, literature in vernacular Bengali began to take shape. The oldest example of Middle Bengali literature is believed to be Shreekrishna Kirtana by Boru Chandidas. In the mid-19th century, Bengali literature gained momentum. During this period, the Bengali Pandits of Fort William College did the tedious work of translating textbooks in Bengali to help teach the British local languages including Bengali. This work played a role in the background in the evolution of Bengali prose.

Religion

The largest religions practised in Bengal are Hinduism and Islam. According to 2014 US Department of State estimates, 90.39% of the population of Bangladesh follow Islam while 8.3% follow Hinduism. In West Bengal, Hindus are the majority with 70.54% of the population while Muslims comprise 27.01%. Other religious groups include Buddhists (comprising around 1% of the population in Bangladesh) and Christians.[68]

Performing arts

Bengali theatre traces its roots to Sanskrit drama under the Gupta Empire in the 4th century CE. It includes narrative forms, song and dance forms, supra-personae forms, performance with scroll paintings, puppet theatre and the processional forms like the Jatra.

Bengal has an extremely rich heritage of dancing dating back to antiquity. It includes classical, folk and martial dance traditions.[69][70]

Arts and science

The Bengali contributions to modern science is path breaking in the world's context. Renowned Indian physicist Satyendranath Bose made first calculations to initiate Statistical Mechanics. He first hypothesised, a physically tangible idea of photon. Meghnad Saha contributed to the theorisation of Thermal Ionization. Jagadish Chandra Bose first practicalised the wireless radio transmission. But Marconi got recognition for European proximity. He also described for the first time, Plants can respond, by demonstrating with his crescograph, recording the impulse caused by bromination of plant tissue.

Sport

Political culture

Bengalis are very active in politics of their region. In West Bengal, India, the chief minister of state is Mamata Banerjee from the party All India Trinamool Congress. In Bangladesh, the Prime Minister of the nation is Sheikh Hasina, belonging to the Awami League party.

See also

- Bengali Renaissance

- Ghosts in Bengali culture

- List of Bangladeshis

- List of Bengalis

- List of people from West Bengal

- States of India by Bengali speakers

Notes

- Includes Bangladeshi Americans, Americans of Bangladeshi descent and Bengali Indian Americans, Americans of Indian descent whose ancestral origins are in West Bengal, the Barak Valley and Tripura

References

- Bengalis at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018) Bengalis at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019) Note: As per discussion on talk page the range is provided since we don't have reliable source for exact number on ethnic group. The range figures are calculated on the basis of L1 speakers, whereas L2 speakers are omitted as they non-Bengalis.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength – 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018.

- "Five million illegal immigrants residing in Pakistan". Express Tribune.

- "Homeless In Karachi". Outlook. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- "Falling back". Daily Times. 17 December 2006. Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- van Schendel, Willem (2005). The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. Anthem Press. p. 250. ISBN 9781843311454.

- "Migration Profile - Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Migration Profile – UAE" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom". Office for National Statistics. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Population of Qatar by nationality – 2017 report". Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- "US Census Bureau American Community Survey (2009–2013) See Row #62". Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "ASIAN ALONE OR IN ANY COMBINATION BY SELECTED GROUPS: 2015". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Aina Nasa (27 July 2017). "More than 1.7 million foreign workers in Malaysia; majority from Indonesia". New Straits Times. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Kuwait restricts recruitment of male Bangladeshi workers". Dhaka Tribune. 7 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- "In pursuit of happiness". Korea Herald. 8 October 2012.

- "Bangladeshis in Singapore". High Commission of Bangladesh, Singapore. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014.

- "Bahrain: Foreign population by country of citizenship". gulfmigration.eu. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "NHS Profile, Canada, 2011, Census Data". Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Census shows Indian population and languages have exponentially grown in Australia". SBS Australia. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 체류외국인 국적별 현황, 《2013년도 출입국통계연보》, South Korea: Ministry of Justice, 2013, p. 290, retrieved 5 June 2014

- バングラデシュ人民共和国(People's Republic of Bangladesh). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan) (in Japanese). Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- http://www.qatar-tribune.com/news.aspx?n=659B1F3A-7299-4D4A-B2DA-D3BAA8AE673D&d=20150625%5B%5D

- Comparing State Polities: A Framework for Analyzing 100 Governments By Michael J. III Sullivan, pg. 119

- "BANGLADESH 2015 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Andre, Aletta; Kumar, Abhimanyu (23 December 2016). "Protest poetry: Assam's Bengali Muslims take a stand". Aljazeera. Aljazeera. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Total Muslim population in Assam is 34.22% of which 85% are Bengali Muslims according to this source which puts the Bengali Muslim percentage in Assam as 29.08%

- Bangladesh- CIA World Factbook

- "Population Housing Census" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "Data on Religion". Census of India (2001). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 26 August 2006.

- "Bangalees and indigenous people shake hands on peace prospects". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- "PART I ¶ THE REPUBLIC ¶ THE CONSTITUTION OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- roughly 163 million in Bangladesh and 100 million in India (CIA Factbook 2014 estimates, numbers subject to rapid population growth); about 3 million Bangladeshis in the Middle East, 1 million Bengalis in Pakistan, 0.4 million British Bangladeshi.

- "50th REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- James Heitzman and Robert L. Worden, ed. (1989). "Early History, 1000 B. C.-A. D. 1202". Bangladesh: A country study. Library of Congress.

- Ahmed, Helal Uddin (2012). "History". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

In C1020 ... launched Rajendra's great northern escapade ... peoples he defeated have been tentatively identified ... 'Vangala-desa where the rain water never stopped' sounds like a fair description of Bengal in the monsoon.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 281. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Land of Two Rivers, Nitish Sengupta

- RIYAZU-S-SALĀTĪN: A History of Bengal Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Ghulam Husain Salim, The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1902.

- "4000-year old settlement unearthed in Bangladesh". Xinhua. 12 March 2006. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007.

- "History of Bangladesh". Bangladesh Student Association @ TTU. Archived from the original on 26 December 2005. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- Chowdhury, AM (2012). "Gangaridai". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Bhattacharyya, PK (2012). "Shashanka". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. Discovery Publishing House. p. 199. ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0.

- Karim, Abdul (2012). "Islam, Bengal". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- A Collection of Treaties and Engagements with the Native Princes and States of Asia: Concluded on Behalf of the East India Company by the British Governments in India, Viz. by the Government of Bengal Etc. : Also Copies of Sunnuds Or Grants of Certain Privileges and Imunities to the East India Company by the Mogul and Other Native Princes of Hindustan. United East-India Company. 1812. p. 28. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, page 202, University of California Press

- Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context, accessed 3 August 2017

- John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 202, Cambridge University Press

- Giorgio Riello, Tirthankar Roy (2009). How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500–1850. Brill Publishers. p. 174. ISBN 9789047429975.

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 9781107507180.

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Nitish Sengupta (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

The Bengal Renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775-1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).

- Georg, Feuerstein (2002). The Yoga Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 600. ISBN 978-3-935001-06-9.

- Clarke, Peter Bernard (2006). New Religions in Global Perspective. Routledge. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-7007-1185-7.

- "A versatile genius". Frontline. Vol. 21 no. 24. 3 December 2004. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- Chatterjee, Santimay and Chatterjee, Enakshi, Satyendranath Bose, 2002 reprint, p. 5, National Book Trust, ISBN 81-237-0492-5

- Sen, A. K. (1997). "Sir J.C. Bose and radio science". Microwave Symposium Digest. IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium. Denver, CO: IEEE. pp. 557–560. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602854. ISBN 0-7803-3814-6.

- Nitish Sengupta (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 213. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

- "Statistical Summaries". Ethnologue. 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Huq, Mohammad Daniul; Sarkar, Pabitra (2012). "Bangla Language". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Tanweer Fazal (2012). Minority Nationalisms in South Asia: 'We are with culture but without geography': locating Sylheti identity in contemporary India, Nabanipa Bhattacharjee.' pp.59–67.

- A community without aspirations Zia Haider Rahman. 2 May 2007. Retrieved on 2018-03-07.

- "C-1 Population By Religious Community - West Bengal". census.gov.in. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Hasan, Sheikh Mehedi (2012). "Dance". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Ahmed, Wakil (2012). "Folk Dances". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

Bibliography and further reading

- Sarkar, Prabhat Ranjan (1988). Bangla o Bangali. Ananda Marga Publications. p. 441. ISBN 978-81-7252-297-1.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 554. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

- Ray, R. (1994). History of the Bengali People. Orient BlackSwan. p. 656. ISBN 978-0863113789.

- Ray, Niharranjan (1994). History of the Bengali people: ancient period. University of Michigan: Orient Longmans. p. 613. ISBN 9780863113789.

- Ray, N (2013). History of the Bengali People from Earliest Times to the Fall of the Sena Dynasty. Orient Blackswan Private Limited. p. 613. ISBN 978-8125050537.

- Das, S.N. (1 December 2005). The Bengalis: The People, Their History and Culture. p. 1900. ISBN 978-8129200662.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin UK. p. 656. ISBN 9788184755305.

- Nasrin, Mithun B; Van Der Wurff, W.A.M (2015). Colloquial Bengali. Routledge. p. 288. ISBN 9781317306139.

- Sengupta, Debjani (22 October 2015). The Partition of Bengal: Fragile Borders and New Identities. Cambridge University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-1107061705.

- Chakrabarti, Kunal; Chakrabarti, Shubhra (1 February 2000). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis (Historical Dictionaries of Peoples and Cultures). Scarecrow Press. p. 604. ISBN 978-0810853348.

- Chatterjee, Pranab (2009). A Story of Ambivalent Modernization in Bangladesh and West Bengal: The Rise and Fall of Bengali Elitism in South Asia. Peter Lang. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-4331-0820-4.

- Singh, Kumar Suresh (2008). People of India: West Bengal, Volume 43, Part 1. University of Virginia: Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1397. ISBN 9788170463009.

- Milne, William Stanley (1913). A Practical Bengali Grammar. Asian Educational Services. p. 561. ISBN 9788120608771.

- Alexander, Claire; Chatterji, Joya (10 December 2015). The Bengal Diaspora: Rethinking Muslim migration. Routledge. p. 304. ISBN 978-0415530736.

- Chakraborty, Mridula Nath (26 March 2014). Being Bengali: At Home and in the World. Routledge. p. 254. ISBN 978-0415625883.

- Sanyal, Shukla (16 October 2014). Revolutionary Pamphlets, Propaganda and Political Culture in Colonial Bengal. Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-1107065468.

- Dasgupta, Subrata (2009). The Bengal Renaissance: Identity and Creativity from Rammohun Roy to Rabindranath Tagore. Permanent Black. p. 286. ISBN 978-8178242798.

- Glynn, Sarah (30 November 2014). Class, Ethnicity and Religion in the Bengali East End: A Political History. Manchester University. p. 304. ISBN 978-0719095955.

- Ahmed, Salahuddin (2004). Bangladesh: Past and Present. Aph Publishing Corporations. p. 365. ISBN 9788176484695.

- Deodhari, Shanti (2007). Banglar Bow (Bengali Bride). AuthorHouse. p. 80. ISBN 9781467011884.

- Gupta, Swarupa (2009). Notions of Nationhood in Bengal: Perspectives on Samaj, C. 1867-1905. BRILL. p. 408. ISBN 9789004176140.

- Roy, Manisha (2010). Bengali Women. University of Chicago Press. p. 232. ISBN 9780226230443.

- Basak, Sita (2006). Bengali Culture And Society Through Its Riddles. Neha Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 9788121208918.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2013). 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh. Harvard University Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0674728646.

- Inden, Ronald B; Nicholas, Ralph W. (2005). Kinship in Bengali culture. Orient Blackswan. p. 158. ISBN 9788180280184.

- Nicholas, Ralph W. (2003). Fruits of Worship: Practical Religion in Bengal. Orient Blackswan. p. 248. ISBN 9788180280061.

- Das, S.N. (2002). The Bengalis: The People, Their History, and Culture. Religion and Bengali culture. volume 4. Cosmo Publications. p. 321. ISBN 9788177553925.

- Schendel, Willem van (2004). The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. Anthem Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-1843311447.

- Mukherjee, Janam (2015). Hungry Bengal : War, Famine, Riots and the End of Empire. Harper Collins India. p. 344. ISBN 978-9351775829.

- Guhathakurta, Meghna; Schendel, Willem van (2013). The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 568. ISBN 978-0822353188.

- Sengupta, Nitish (19 November 2012). Bengal Divided: The Unmaking of a Nation (1905-1971). Penguin India. p. 272. ISBN 978-0143419556.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bengali people. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bengalis |