Nawabs of Bengal and Murshidabad

The Nawabs of Bengal (the Nawab Nazim of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa) were Muslim rulers of Bengal, and significant portions of present-day Bihar and Orissa. With their capital in Murshidabad, they ruled the Mughal Bengal subah, while nominally subordinate to the Mughal empire, in between 1717 and 1772. Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal, lost the Battle of Plassey to the British East India Company in 1757. He was betrayed by Mir Jafar in the battle, who was subsequently installed as the titular Nawab Nazim. Following the victory in Plassey and later in Buxar, the British East India Company established itself as a strong political power-hold in the region of Bengal. In 1765, the system of dual government came to be established, as per which the East India company collected all the revenue, while the Nawab was responsible for running the administration of the province. In 1772, the system was abolished and Bengal was brought under direct control of the Company. When the nizamat (administration, judicial, and military powers) of the Nawab was also taken away in 1793, they remained as the mere pensioners of the Company.[2][3] Following the abolition of the title of Nawab of Bengal in 1880, the last Nawab of Bengal, Mansur Ali Khan, abdicated on 1 November 1880, in favour of his eldest son, Hassan Ali Mirza.[4]

| Nawab Nazim of Bengal (1717–1880)a Nawab Bahadur of Murshidabad (1882–1971)b | |

|---|---|

_and_that_of_the_Nawab_of_Murshidabad_(bottom).png) Coat of arms of the Nawab Nazim (top) and that of the Nawab Bahadur (bottom) | |

| Creation | 1717 |

| First holder | Murshid Quli Khan |

| Last holder | Waris Ali Mirza |

| Present holder | Abbas Ali Mirza |

| Status | De facto only, not de jure |

| Extinction date | 1971 |

| Seat(s) | Murshidabadc |

| Former seat(s) | Hazarduari Palace, Murshidabad |

| Motto | Nil Desperandum (There is no cause for despair, never despair) |

| a. Title abolished in 1880, succeeded as the Nawab Bahadur of Murshidabad. b. Derecognition of rulers and abolition of Privy Purse by the twenty-sixth amendment of the Indian Constitution, in 1971.[1] c. Murshidabad was the capital for both the Nawab Nazims and the Nawab Bahadurs. | |

The Nawabs of Murshidabad (Nawab Bahadur of Murshidabad) succeeded the Nawabs of Bengal, following Mansur Ali Khan's abdication[5] They had no direct control in the share of the revenue collected and could not use military force. The fourth Nawab Bahadur, Waris Ali Mirza died in 1969, and a long dispute over succession ensued.[6] Meanwhile, the policy of Privy Purse, which had allowed nobles to keep some of their privileges and titles, stood abolished in 1971 by the twenty-sixth amendment of the Constitution of India, derecognising all such rulers. Eventually, in August 2014, the Supreme Court of India decided on the dispute over succession to Waris Ali, in which one Abbas Ali Mirza was declared to be his lawful heir; Waris Ali Mirza was his maternal uncle. The hereditary title today is de facto only as it is not recognised by Indian law.

Bengal

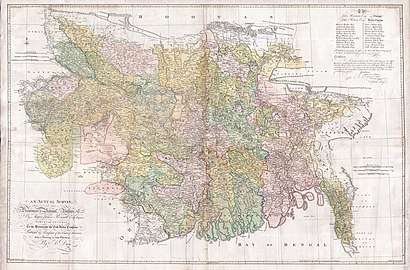

Bengal is a region encompassing present-day Bangladesh and the state of West Bengal in India.[7][8] During the partition of Bengal in 1905, East Bengal was carved out of the Bengal Presidency as a Lieutenant-Governorship along with Assam.[9] In 1911, East Bengal was reunited with the rest of Bengal.[10] The Nawab's rule extended beyond the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal to parts of present-day Orissa and Bihar.[11][12][13][14] The majority of present-day Bengal is inhabited by a Bengali-speaking populace.[15]

- Maps of Bengal

Present-day Bengal includes Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal

Present-day Bengal includes Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal Map of Bengal and Bihar, dated 1776

Map of Bengal and Bihar, dated 1776

History before the Nawab's rule

Sultans of Bengal

The early Sultans of Bengal ruled until 1282 and were succeeded by several successive dynasties. Sultan Ilyas Shah, founder of the Ilyas Shahi dynasty, took complete charge of Bengal under his rule.[16] The Sultanate capital was shifted to Sonargaon.[17] His son, Sikandar Shah, who succeeded him, built Adina Mosque at Pandua, near Gaur, which is considered to be the largest in undivided Bengal.[18]

Mughal empire

The Mughal empire emerged as a powerful empire in northern India. Babur, who was related to two legendary warriors – Timur and Genghis Khan, invaded north India and defeated Ibrahim Lodi.[19] He was succeeded as the second Mughal emperor by his son Humayun. At the same time, Sher Shah Suri of the Suri dynasty rose to prominence and established himself as the ruler of present-day Bihar by defeating Ghiyasuddin Shah III. But he lost to capture the kingdom because of the sudden expedition of Humayun. In 1539, Sher Khan faced Humayun in the Battle of Chausa and forced him out of India. Assuming the title Sher Shah, he ascended the throne of Delhi. He also captured Agra and established control from Bengal in the east, to the Indus river in the west.[20] After his death he was succeeded by his son, Islam Shah Suri. However, in 1544 the Suris were torn apart by internal conflicts. Humayun took this advantage and captured Lahore and Delhi.[21] Succeeded by Akbar, Sultan Daud Khan Karrani of Bengal was defeated. After this, the administration of the entire region passed on to the hands of Mughal empire appointed governors.[22][23][24] The Bengal subah was the wealthiest subah of the Mughal empire.[25] There were several posts under the Mughal administrative system during Akbar's reign. nizamat and diwani were the two main branches of provincial administration under the Mughals.[22] A subahdar was in-charge of the nizamat, and they had a chain of subordinate officials on the executive side, while diwans had subordinates on the revenue and judicial side.[22]

As the Mughal empire began to decline, the Nawabs rose in power, although nominally subordinate to the Mughal emperor.[22][26] Eventually, with the process of regional centralisation of the Mughal empire, they came to wield greater power for all practical governance purposes by the early 1700s.[26]

History during the Nawab's rule

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bengal |

|

|

Ancient Geopolitical units

|

|

Ancient and Classical dynasties

|

|

Medieval and Early Modern periods

|

|

European colonisation

|

|

East Bengal (1947–1955)

|

|

West Bengal (1947–present)

|

|

East Pakistan (1955–1971)

|

|

Bangladesh (1971–present)

|

|

Calendar

|

|

Museums of antiquities

|

|

Related

|

Emergence of the Nawab Nazim

Murshid Quli Khan arrived as the diwan of Bengal in 1717. He was preceded by four Diwans of the Bengal subah. Post his arrival, Azim-ush-Shan held the nizam's office. Azim got into a conflict with Murshid Quli Khan over financial control. Considering the complaint of Khan, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb transferred Azim to Bihar.[27] Upon his departure, the two posts of nizamat and diwani got unified into the office held by Murshid Quli Khan. Murshid came to be known as the Nawab Nazim of Bengal.[22][28] Murshidabad remained the capital of the Nawabs Nazims throughout the duration of their rule.[22][29] Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah, the third Nawab Nazim, was betrayed in the Battle of Plassey by Mir Jafar.[30] He lost to the British East India Company, who took installed Mir Jafar as the succeeding Nawab, and established itself as a strong political power-hold in Bengal.[31]

In 1765, Robert Clive became the first Governor of Bengal.[32] He secured for the Company the diwani of the Bengal subah in perpetuity, from the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II. With this the system of dual governance was established and the Bengal Presidency was formed. In 1772, this arrangement came to be abolished and Bengal was brought under direct control of the British. In 1793, when the nizamat of the Nawab was also taken away they remained as the mere pensioners of the Company. After the Revolt of 1857, Company rule in India ended, and the British Crown, in 1858, took over the territories which were under direct rule of the Company. This marked the beginning of the British Raj, and the Nawabs had no political or any other kind of control over the territory.[33][34] The last Nawab of Bengal, Mansur Ali Khan, abdicated on 1 November 1880, in favour of his eldest son.[4]

Dynasties of the Nawabs

_being_a_synopsis_of_the_history_of_Murshidabad_for_the_last_two_centuries%2C_to_which_are_appended_notes_of_places_and_objects_of_interest_at_Murshidabad_(1905)_(14776529292).jpg)

From 1717 until 1880, three successive dynasties – Nasiri, Afshar, and Najafi – ruled as the Nawab Nazims of Bengal.[35]

The first dynasty, Nasiri, ruled from 1717 until 1740. The founder of the Nasiri dynasty, Murshid Quli Khan, was born in a Deccani Odia Brahmin family, before being sold into slavery and bought by one Haji Shafi Isfahani, a Persian merchant from Isfahan. He was then initiated into Islam. He entered the service of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and rose through the ranks. He was succeeded by his son-in-law, Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan.[28] After Shuja-ud-Din's death, in 1739, he was succeeded by his son, Sarfaraz Khan, who held the rank, until he was killed in the Battle of Giria in 1741, and was succeeded by Alivardi Khan, erstwhile ruler of Patna, of the Afshar Dynasty in 1740.[36]

The second dynasty, the Afshars, ruled from 1740 to 1757. Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah, Alivardi Khan's grandson, the last Afshar Nawab, was killed in the Battle of Plassey in 1757.[37] They were succeeded by the third and final dynasty, namely the Najafis.[22]

Nominal control of Bihar

The Zamindars of Bihar maintained a tenuous loyalty to the Nawabs of Bengal.[38] Rebellion and the withholding of revenue was a common feature of the Nawab period in Bihar. In fact, when the British gained control of Bihar, they realised that one quarters of revenue in Bihar had been withheld from the state.[39] A prominent example of this were the zamindars of Raj Darbhanga in North Bihar were legally independent from Nawabs and refused to pay tribute and revenue to them.[40]

A major rebellion against the Nawabs of Bengal was led by the Ujjainiya Rajput chiefs of Bhojpur in West Bihar in 1760 during the reign of Mir Qasim. This rebellion was a serious blow to the Nawabs rule in Bihar and they faced great difficulty in subduing them.[41] Although Bihar had the potential to provide a large amount of revenue and tax, records show that the Nawabs were unable to extract any money from the chiefs of Bihar until 1748. And even following this, the amount gained was very low. This was again due to the rebellious nature of the zamindars who were "continually in arms".[42]

Maratha expeditions

Marathas undertook six expeditions in Bengal from 1741–1748. Maratha general, Raghunath Rao was able to annex Orissa into his kingdom and the larger confederacy permanently, as he successfully exploited the chaotic conditions prevailing in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa after the death of Murshid Quli Khan in 1727.[43] Constantly attacked by the Bhonsles, Orissa, Bengal, and parts of Bihar were economically ruined. Alivardi Khan made peace with Raghunathrao in 1751 ceding in perpetuity the territory of Orissa up to the river Subarnarekha. He also agreed to pay ₹12 lacs annually in lieu of the Chauth of Bengal and Bihar.[44] The treaty also included a sum of ₹12 lacs for Bihar. The Marathas promised to never to cross the boundary of the Nawab's territory.[45] Baji Rao is often hailed for his success in subjecting the rulers of east India to Maratha dominance.[46]

The Nawabs under British rule and their decline

The regional centralisation of the Mughal empire by 1750, led to the creation of numerous semi-independent power-holds in the Mughal provinces. Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah was defeated by British forces of Robert Clive in the Battle of Plassey, in 1757.[37] Thereafter, the Nawab of Bengal had to depend on the British East India company for military support.[37]

Siraj-ud-Daula was succeeded by Mir Jafar, who had supported Clive in the 1757 Battle.[37] He briefly tried to re-assert his dominance by allying with the Dutch, but this failed following the Battle of Chinsurah.

After the defeat of Jafar at the Battle of Buxar and grant of the diwani of Bengal by Mughal emperor Shah Alam II to the British East India Company, in August 1765, and the subsequent appointment of Warren Hastings as the first Governor General of Bengal, in 1773, the Nawab's authority stood severely restricted. By 1773, the Company asserted its authority and formed the Bengal Presidency, including significant areas ruled by the Nawabs, along with other regions. The Company also abolished the system of dual governance.

In 1793, the nizamat was abolished by the Company. It took complete control of the region and the Nawabs stood as mere pensioners of the Company. The diwan offices except the diwan ton were also abolished.[33][34][47]

After the Revolt of 1857, Company rule in India ended, and all territories under the control of the Company came under direct control of the British Crown in 1858, marking the beginning of the British Raj. The administrative control of India came under the Indian Civil Service, which had administrative control over all areas in India, except the princely states. However, the Nawab's territory did not qualify as a princely state.[10]

Nawab Mansur Ali Khan was the last titular Nawab Nazim of Bengal. During his reign the nizamat at Murshidabad came to be debt-ridden. The Nawab left Murshidabad in February 1869, and had started living in England. The title of the Nawab of Bengal stood abolished in 1880.[4] He returned to Bombay in October 1880 and pleaded his case against the orders of the government, but as it stood unresolved the Nawab renounced his styles and titles, abdicating in favour of his eldest son at St. Ives, Maidenhead, on 1 November 1880.[4]

Emergence of the Nawab Bahadur and the Nawabs post Indian independence

The Nawabs of Murshidabad succeeded the Nawab Nazims following Nawab Mansur Ali Khan's abdication.[22][4][5] The Nawab Bahadurs had ceased to exercise any significant power.[22][48] Preceding Indian Independence in 1947, the Radcliffe Line divided the British provinces of Bengal and Punjab on religious lines.[49] Murshidabad, the capital city of the Nawab Nazims and the Nawab Bahadurs, came to be a part of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) for two days, as it had a Muslim majority populace. It became a part of India only on 17 August 1947.[50] Subsequently, the Pakistani flag was brought down from the Nawab's Hazarduari Palace and the Indian tricolour was hoisted atop.[51]

With the promulgation of the Indian Constitution on 26 January 1950, under Article 18 , the state was prevented from conferring any titles except those given to individuals who have made their mark in military and academic fields. However, under the policy of the Privy Purse, nobles were allowed to keep certain privileges and their titles.

In 1959, Wasif Ali Mirza came to be the third Nawab Bahadur.[49] He was succeeded by Waris Ali Mirza who died in 1969,[52] survived by three sons and three daughters. His death was followed by a long-standing dispute over succession as he had excluded his eldest son, Wakif Ali Mirza, from the succession for contracting a non-Muslim marriage and for not professing Islam. War is Ali took no steps during his lifetime to establish his successor. His will stood disputed.[6]

Meanwhile, in 1971, the Privy Purse policy was abolished by the twenty-sixth amendment of the Indian constitution. Hence, the title of the Nawab Bahadur ceased to enjoy legal sanctity.[1][6][53]

The dispute over the succession ensued a legal battle. One Abbas Ali Mirza claimed to be Waris Ali's lawful heir on the basis of him being the grandson of Wasif Ali Mirza, through his only daughter; while Sajid Ali Mirza claimed the same on the basis of being the son of Wasif Ali, through a mut‘ah marriage. The dispute was decided in the Supreme Court on 13 August 2014, by Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice R. K. Agrawal. The court declared Abbas Ali Mirza as the lawful heir of Waris Ali. However, the case challenging the overtaking of the Murshidabad estate by the state, worth several thousand crores, is still pending as of 2014.[52][54]

List of the Nawabs of Bengal

The following is a list of the Nawabs of Bengal. Sarfaraz Khan and Mir Jafar were the only two to become Nawab Nazim twice.[55] The chronology started in 1717 with Murshid Quli Khan and ended in 1880 with Mansur Ali Khan.[22][4][55]

| Portrait | Titular Name | Personal Name | Birth | Reign | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasiri dynasty | |||||

|

Jaafar Khan Bahadur Nasiri | Murshid Quli Khan | 1665 | 1717–1727 | June 1727[28][56][57] |

|

Ala-ud-Din Haidar Jung | Sarfaraz Khan | After 1700 | 1727-1727 (for few days) | 29 April 1740[36] |

|

Shuja ud-Daula | Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan | circa 1670 | 1 July 1727 – 26 August 1739 | 26 August 1739[58][59] |

|

Ala-ud-Din Haidar Jung | Sarfaraz Khan | After 1700 | 13 March 1739 – 29 April 1740 | 29 April 1740[36] |

| Afshar dynasty | |||||

|

Hashim ud-Daula | Alivardi Khan | Before 10 May 1671 | 29 April 1740 – 9 April 1756 | 9 April 1756[60][61] |

|

Siraj ud-Daulah | Siraj ud-Daulah | 1733 | 9 April 1756 – 23 June 1757 | 2 July 1757[62][63] |

| Najafi dynasty | |||||

_and_Mir_Miran_(right).jpg) |

Ja'afar 'Ali Khan Bahadur | Mir Jafar | 1691 | 2 June 1757 – 20 October 1760 | 17 January 1765[64][65][66] |

|

Itimad ud-Daulah | Mir Qasim | ? | 20 October 1760 – 7 July 1763 | 8 May 1777[67] |

_and_Mir_Miran_(right).jpg) |

Ja'afar 'Ali Khan Bahadur | Mir Jafar | 1691 | 25 July 1763 – 17 January 1765 | 17 January 1765[67][68] |

|

Najm ud-Daulah | Najmuddin Ali Khan | 1750 | 5 February 1765 – 8 May 1766 | 8 May 1766[69] |

|

Saif ud-Daulah | Najabut Ali Khan | 1749 | 22 May 1766 – 10 March 1770 | 10 March 1770[70] |

| Ashraf Ali Khan | Before 1759 | 10 March 1770 – 24 March 1770 | 24 March 1770 | ||

|

Mubarak ud-Daulah | Mubarak Ali Khan | 1759 | 21 March 1770 – 6 September 1793 | 6 September 1793[71] |

|

Azud ud-Daulah | Baber Ali Khan | ? | 1793 – 28 April 1810 | 28 April 1810[72] |

|

Ali Jah | Zain-ud-Din Ali Khan | ? | 5 June 1810 – 6 August 1821 | 6 August 1821[73][74] |

|

Walla Jah | Ahmad Ali Khan | ? | 1821 – 30 October 1824 | 30 October 1824[75][76] |

|

Humayun Jah | Mubarak Ali Khan II | 29 September 1810 | 1824 – 3 October 1838 | 3 October 1838[77][78][79] |

|

Feradun Jah | Mansur Ali Khan | 29 October 1830 | 29 October 1838 – 1 November 1880 (abdicated) | 5 November 1884[4] |

List of the Nawabs of Murshidabad

The Nawabs of Murshidabad succeeded the Nawabs of Bengal.[22][4] Waris Ali Mirza was the last Nawab to hold the title legally. Abbas Ali Mirza has been recognised as the lawful heir of Waris Ali. The title today is de facto only and is devoid of any legal sanctity.[1]

| Picture | Titular Name | Personal Name | Birth | Reign | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Najafi dynasty | |||||

|

Ali Kadir | Hassan Ali Mirza | 25 August 1846 | 17 February 1882 – 25 December 1906 | 25 December 1906[80][5] |

|

Amir ul-Omrah | Wasif Ali Mirza | 7 January 1875 | December 1906 – 23 October 1959 | 23 October 1959[80][81] |

|

Raes ud-Daulah | Waris Ali Mirza | 14 November 1901 | 1959 – 20 November 1969 | 20 November 1969[6] |

| N/A | N/A | Disputed/In abeyance[52][54] | N/A | 20 November 1969 – 13 August 2014 | N/A |

|

N/A | Abbas Ali Mirza | circa 1942 | 13 August 2014 (declared lawful heir)[52][54] | N/A |

References

- "Twenty Sixth Amendment to the Indian Constitution". Indiacode.nic.in. 28 December 1971. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Singh, Vipul (2009). Longman History & Civics (Dual Government in Bengal). Pearson Education India. pp. 29–. ISBN 9788131728888. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Madhya Pradesh National Means-Cum-Merit Scholarship Exam (Warren Hasting's system of Dual Government). Upkar Prakashan. 2009. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-81-7482-744-9.

- "Murshidabad History - Feradun Jah". Murshidabad.net. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Hassan Ali Mirza's succession". Murshidabad.net. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Murshidabad History - Waresh Ali". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary (Third ed.). Merriam-Webster. 1997. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-87779-546-9.

- Chakraborty, Mridula Nath (2014). Being Bengali: At Home and in the World. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-317-81890-8.

- Ray, Asok Kumar; Chakraborty, Satyabrata (2008). Society, Politics, and Development in North East India: Essays in Memory of Dr. Basudeb Datta Ray. Concept Publishing Company. p. 195. ISBN 9788180695728.

- David Gilmour, The Ruling Caste: Imperial Lives in the Victorian Raj (2007) pp. 46, 135

- Sir James Bourdillon The Partition of Bengal (London: Society of Arts) 1905

- "History of Bangladesh". Bangladesh Student Association. Archived from the original on 19 December 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- "Britain Proposes Indian Partition". Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada: The Leader-Post. BUP. 2 June 1947. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- "Nawabs of Bengal were also known as Nawabs of Bengal and Orissa". Murshidabad.nic.in. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Huq, Mohammad Daniul; Sarkar, Pabitra (2012). "Bangla Language". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015.

- Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, p.197

- Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, p.212

- Husain, ABM (2012). "Adina Mosque". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

- "Babu, the First Moghul Emperor: Wine and Tulips in Kabul". The Economist: 80–82. 16 December 2010. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017.

- "Sher Khan". Columbia Encyclopedia. 2010. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- "Biography of Islam Shah the Successor of Sher Shah". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- "Murshidabad History - The Nawabs and Nazims". Murshidabad.net. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Ahmed, ABM Shamsuddin (2012). "Daud Khan Karrani". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015.

- The History of India: The Hindú and Mahometan Periods By Mountstuart Elphinstone, Edward Byles Cowell, Published by J. Murray, 1889, Public Domain

- "Bengal subah was one the richest subahs of the Mughal empire". Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Sen, S. N. (2006). History Modern India – S. N. Sen – Google Books. ISBN 9788122417746. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- Chatterjee, Anjali (2012). "Azim-us-Shan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Murshidabad History - Murshid Quli Khan". Murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Mohsin, KM (2012). "Murshidabad". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Hist & Civics Viii Mat Board. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. 2005. p. 10. ISBN 9780070604452. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Review Projector (India). T.R. Kesava Murthy. 1985. p. 31. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Chaudhury, Sushil; Mohsin, KM (2012). "Sirajuddaula". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015.

- Singh, Vipul (1 September 2009). Longman History & Civics (Dual Government in Bengal). Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131728888. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Madhya Pradesh National Means-Cum-Merit Scholarship Exam (Warren Hasting's system of Dual Government). Upkar Prakashan. 1 January 2009. ISBN 9788174827449.

- Rahman, Urmi (23 December 2014). Bangladesh - Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture. Bravo Limited. ISBN 9781857336962. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "Murshidabad History - Sarfaraz Khan". Murshidabad.net. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "Defeat of Siraj-ud-Daulah in the Battle of Plassey". Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- P. J. Marshall (2 November 2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6.

- Kumkum Chatterjee (1996). Merchants, Politics, and Society in Early Modern India: Bihar, 1733-1820. BRILL. pp. 35–36. ISBN 90-04-10303-1. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- J. Albert Rorabacher (13 September 2016). Bihar and Mithila: The Historical Roots of Backwardness. Taylor & Francis. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-1-351-99758-4.

- Tahir Hussain Ansari (20 June 2019). Mughal Administration and the Zamindars of Bihar. Taylor & Francis. pp. 281–285. ISBN 978-1-00-065152-2.

- P. J. Marshall (2 November 2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–60. ISBN 978-0-521-02822-6.

- SNHM. Vol. II, pp. 209, 224.

- Wernham, R. B. (1 November 1968). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 3, Counter-Reformation and Price Revolution, 1559–1610 (Maratha invasion of Bengal). CUP Archive. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1 January 1991). Fall Of The Mughal Empire- Vol. I (4Th Edn.) (Maratha Chauth from Bihar). Orient Blackswan. ISBN 9788125011491. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- George Michell and Mark Zebrowski (10 June 1999). Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates, Volumes 1-7 (Maratha raids in Bihar). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521563215. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Incidents during Mubarak ud-Daulah's reign". Murshidabad.net. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "The Nawabs of Murshidabad had little or no say". Royal Ark. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Lumby 1954, p. 232

- Prakash, Ved (2008). Terrorism in India's North-east: A Gathering Storm. Gyan Publishing House. p. 350. ISBN 9788178356617.

- "Nawabs' Murshidabad House lies in tatters". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Mahato, Sukumar (20 August 2014). "Murshidabad gets a Nawab again, but fight for assets ahead". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- "Article 18 of Indian Constitution and Abolition of Titles". GK Today. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Portrait of an accidental Nawab". Times of India. 22 August 2014. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- "The Nawabs of Bengal (chronologically)". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- "Murshid Quli Khan | Indian nawab". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Karim, Abdul (2012). "Murshid Quli Khan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017.

- Karim, KM (2012). "Shujauddin Muhammad Khan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Suja-ud-Daulla". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Alivardi Khan". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Bengal, Past & Present: Journal of the Calcutta Historical Society. The Society. 1962. pp. 34–36. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Siraj-ud-Daulla". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah". Story Of Pakistan. 3 January 2005. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Zaidpūrī, Ghulām Ḥusain (called Salīm) (1902). The Riyaz̤u-s-salāt̤īn: A History of Bengal. Asiatic Society. p. 384. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Mir Muhammed Jafar Ali Khan". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Portrait of an accidental Nawab". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Shah, Mohammad (2012). "Mir Jafar Ali Khan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015.

- Bibliotheca Indica. Baptist Mission Press. 1902. p. 397. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Najam-ud-Daulla". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Saif-ud-Daulla". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Khan, Abdul Majed (3 December 2007). The Transition in Bengal, 1756-75: A Study of Saiyid Muhammad Reza Khan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521049825.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Babar Ali Delair Jang". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Ali Jah". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Majumdar, Purna Chundra (1905). The Musnud of Murshidabad (1704-1904): being a synopsis of the history of Murshidabad for the last two centuries, to which are appended notes of places and objects of interest at Murshidabad. Saroda Ray. pp. 49.

Ali Jah Murshidabad.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Wala Jah". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Indian Records: With a Commercial View of the Relations Between the British Government and the Nawabs Nazim of Bengal, Behar and Orissa. G. Bubb. 1870. pp. 75. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Paul, Gautam. "Murshidabad History - Humayun Jah". murshidabad.net. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Majumdar, Purna Chundra (1905). The Musnud of Murshidabad (1704-1904): being a synopsis of the history of Murshidabad for the last two centuries, to which are appended notes of places and objects of interest at Murshidabad. Saroda Ray. pp. 50.

Humayun Jah.

- Ray, Aniruddha (13 September 2016). Towns and Cities of Medieval India: A Brief Survey. Routledge. ISBN 9781351997300.

- "MURSHID16". www.royalark.net. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Company, East India (1807). Papers Presented to the House of Commons Concerning the Late Nabob of the Carnatic. p. 118.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nawabs of Bengal and Murshidabad |