Women in World War I

Women in World War I were mobilized in unprecedented numbers on all sides. The vast majority of these women were drafted into the civilian work force to replace conscripted men or work in greatly expanded munitions factories. Thousands served in the military in support roles, e.g. as nurses, but in Russia some saw combat as well.

Austria

In late July 1914 the Viennese press circulated a message published by Austria's first major women's group, the Frauenhifsaktion Wien, appealing to "Austria's women" to perform their duties to the nation and take part in the war effort. Women would be expected to provide much of the necessary manpower during this time and depending on the social class some would even take part in the leadership of local communities in Austria.[1]

Viktoria Savs served as a soldier in the Imperial Austrian army in the guise of a man and was awarded with the Medal for Bravery (Austria-Hungary) for valor in combat for her service in the Dolomitian front.[2]

Great Britain

In the military

Dorothy Lawrence was an English journalist who posed as a male soldier in order to report from the front line during World War I. She was the only known English woman soldier on the frontline during World War I. In her later book, Lawrence wrote she was a sapper with the 179 Tunnelling Company, 51st Division, Royal Engineers,a specialist mine-laying company that operated within 400 yards (370 m) of the front line. But later evidence and correspondence from the time after her discovery by British Army authorities, including from the files of Sir Walter Kirke of the BEF's secret service, suggest she actually was at liberty and working within the trenches. The toll of the job, and of hiding her true identity, soon gave her constant chills and rheumatism, and latterly fainting fits. Concerned that if she needed medical attention her true gender would be discovered and the men who had befriended her would be in danger, after 10 days of service she presented herself to the commanding sergeant, who promptly placed her under military arrest. She was sent home under a strict agreement not to publish her experiences.[3][4]

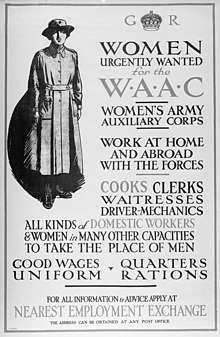

Women also volunteered and served in the military without disguising themselves; by the end of the war, 80,000 had enlisted.[5][6] They mostly served as nurses in the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), founded in 1907, also known as the “Princess Royal’s Volunteer Corps”; the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD); and from 1917, in the Army when the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), was founded.[7] The WAAC was divided into four sections: cookery; mechanical; clerical and miscellaneous. Most stayed on the Home Front, but around 9,000 served in France.[7]

Munitions factories

.jpg)

Large numbers of women were hired in the munitions industries. They were let go when the munitions industries downsized at the end of the war. They volunteered for the money, and for patriotism. The wages were doubled of what they had previously made. The women working in these munitions factories were called "Munitionettes"; another nickname for these women was the "Canaries" because of the yellow skin which came from working with toxic chemicals. The work which these women did was long, tiring and exhausting as well as dangerous and hazardous to their health.[8]

The women working in munitions factories were from mainly lower-class families and were between the ages of 18 and 29 years old.[9][10] A critical role consisted of making gun shells, explosives, aircraft and other materials that supplied the war at the front,[11] which was dangerous and repetitive work because they were constantly around and encased in toxic fumes as well as handling dangerous machinery and explosives. Some women would work long hours.[12] The factories all over Britain in which women worked were often unheated, deafeningly noisy, and full of noxious fumes and other dangers.[12] Some of the common diseases and illness which occurred were drowsiness, headaches, eczema, loss of appetite, cyanosis, shortness of breath, vomiting, anaemia, palpitation, bile stained urine, constipation, rapid weak pulse, pains in the limbs and jaundice and mercury poisoning.[13]

Oftentimes after the war as well women would end up losing their jobs as men returned home from the war, gaining no recognition for the effort women put in to aid in the war efforts.

Poster campaign

Propaganda, in the form of posters to entice women to join the factory industry in World War I, did not represent the dangerous aspects of female wartime labour conditions.[14] The posters failed to represent an accurate account of reality by creating a satisfactory appeal for women who joined the workforce and did their part in the war. Designed for women to persuade their men to join the armed forces, one propaganda poster is a romantic setting as the women look out an open window into nature as the soldiers march off to war. The poster possesses a sentimental and romantic appeal when the reality of the situation was that many women endured extreme hardships when their husbands enlisted.[14] It was this narrative of a false reality conveyed in the visual propaganda that aimed to motivate war effort. The Edwardian social construction of gender was that women should be passive and emotional, and have moral virtue and domestic responsibility. Men on the other hand were expected to be active and intelligent, and to provide for their families. It was this idea of gender roles that poster propaganda aimed to reverse. In one war propaganda poster, titled “These Women Are Doing Their Bit”, a woman is represented as making a sacrifice by joining the munitions industry while the men are at the front. The woman in this particular persuasive poster is depicted as cheerful and beautiful, ensuring that her patriotic duty will not reduce her femininity.[14] These posters do not communicate the reality that munitions labour entails. There is no reference to highly explosive chemicals or illnesses due to harsh work environments. The persuasive images of idealized female figures and idyllic settings were designed to solicit female involvement in the war and greatly influenced the idea of appropriate feminine behavior in the wartime Britain. As a result, many women left their domestic lives to join munitions work as they were enticed by what they thought were better living conditions, patriotic duty and high pay.[14] According to Hupfer, the female role in the social sphere was expanded as they joined previously male-dominated and hazardous occupations (325).[14] Hupfer remarks that attitudes regarding the capabilities of women through the war effort sank back into the previously idealized roles of women and men once the war was over. Women went back to their duty in the home as they lost their jobs to returning soldiers and female labour statistics decreased to pre-war levels. Not until 1939 would the expansion of the role of women once again occur.[14]

Jobs on the home front other than in munitions factories

Many women volunteered on the home front as nurses, teachers, and workers in traditionally male jobs.[15] Wealthy women set up an organization called the American Women's War Relief Fund in England in 1914 order to buy ambulances, support hospitals and provide economic opportunities to women during the war.[16][17][18]

Australia

The role of Australian women in World War I was focused mainly upon their involvement in the provision of nursing services.[19] 2,139 Australian nurses served during World War I. Their contributions were more important than initially expected, resulting in more respect for women in medical professions.

Some women made ANZAC biscuits which were shipped to the soldiers. The biscuits were made using a recipe that would allow them to remain edible for a long time without refrigeration.

Canada

In December 1914, Julia Grace Wales published the Canada Plan, a proposal to set up a mediating conference consisting of intellectuals from neutral nations who would work to find a suitable solution for the First World War. The plan was presented to the United States Congress, but despite arousing the interest of President Wilson, failed when the US entered the war.[20][21]

During World War One, there was virtually no female presence in the Canadian armed forces, with the exception of the 3141 nurses serving both overseas and on the home front.[22] Of these women, 328 had been decorated by King George V, and 46 gave their lives in the line of duty.[22] Even though a number of these women received decorations for their efforts, many high-ranking military personnel still felt that they were unfit for the job. Although the Great War, had not officially been opened up to women, they did feel the pressures at home. There had been a gap in employment when the men enlisted; many women strove to fill this void along with keeping up with their responsibilities at home.[22] When war broke out Laura Gamble enlisted in the Canadian Army Medical Corps, because she knew that her experience in a Toronto hospital would be an asset to the war efforts.[23] Canadian nurses were the only nurses of the Allied armies that held the rank of officers.[23] Gamble was presented with a Royal Red Cross, 2nd Class medal, for her show of “greatest possible tact and extreme devotion to duty.” [23] This was awarded to her at Buckingham Palace during a special ceremony for Canadian nurses.[23] Health care practitioners had to deal with medical anomalies they had never seen before during the First World War. The chlorine gas that was used by the Germans caused injuries that treatment protocols had not yet been developed for. The only treatment that soothed the Canadian soldiers affected by the gas was the constant care they received from the nurses.[23] Canadian nurses were especially well known for their kindness.[23]

Canadians had expected that women would feel sympathetic to the war efforts, but the idea that they would contribute in such a physical way was absurd to most.[22] Because of the support that women had shown from the beginning of the war, people began to see their value in the war. In May 1918, a meeting was held to discuss the possible creation of the Canadian Women’s Corps. In September, the motion was approved, but the project was pushed aside because the war’s end was in sight.[22]

On the Canadian home front, there were many ways which women could participate in the war effort. Lois Allan joined the Farm Services Corps in 1918, to replace the men who were sent to the front.[24] Allan was placed at E.B. Smith and Sons where she hulled strawberries for jam.[24] Jobs were opened up at factories as well, as industrial production increased.[24] Work days for these women consisted of ten to twelve hours, six days a week. Because the days consisted of long monotonous work, many women made up parodies of popular songs to get through the day and boost morale.[24] Depending on the area of Canada, some women were given a choice to sleep in either barracks or tents at the factory or farm that they were employed at.[24] According to a brochure that was issued by the Canadian Department of Public Works, there were several areas in which it was appropriate for women to work. These were:

- On fruit or vegetable farms.

- In the camps to cook for workers.

- On mixed and dairy farms.

- In the farmhouse to help feed those who are raising the crops.

- In canneries, to preserve the fruit and vegetables.

- To take charge of milk routes.[25]

In addition, many women were involved in charitable organization such as the Ottawa Women’s Canadian Club, which helped provide the needs of soldiers, families of soldiers and the victims of war.[24] Women were deemed ‘soldiers on the home front’, encouraged to use less of nearly everything, and to be frugal in order to save supplies for the war efforts.[24]

Finland

In the 1918 Finnish Civil War, more than 2,000 women fought in the Women's Red Guards formed in early February with more than 15 female guard units. As the commanders of the Red Guard were reluctant to commit female guards to combat most of the female guards were held in reserve for much of the civil war, only seeing combat towards the end of the war, in battles such as the Battle of Tampere where the city hall was held by the last pockets of Red Guard resistance, legends tell of how the male defenders wanted to surrender while the Tampere Women's Red Guard insisted on fighting to the bitter end. At the end of the civil war over 755 Red Guard women had died, with only 70 to 130 of them killed on the battlefield, over 20% or 400 to 500 members would be executed by the anti-communist White Guard victors and 80 to 110 died in prison camps with 150 to 200 members AWOL.[26]

As such it is clear that women played a role in the Finnish war both during the first world war when the women's military divisions would be conceptualized with some women already serving in the military and towards the end during the civil war when it would be formed by the Red Guard in reality.

Ottoman Empire

Women had limited front line roles being nurses and provided a subsidiary work force of emergency medical personnel in substitution for the lack of manpower available as the empire was battling multiple fronts of enemies forcing the conscription of most of its male population, this medical workforce of women was all possible through organizations created by the government and international organizations such as the Red Cross.[27]

Women such as Safiye Huseyin risked her life working on the Resit Pasa Hospital Ship for wounded soldiers. This ship took in wounded Ottoman soldiers from the Dardanelles and was oftentimes bombarded by enemy planes and other ships.[28]

Women were also given limited roles in employment positions by the IOEW (Islamic Organization for the Employment of Women), an organization formed in 1916 with the aim to "protect women by finding them work and by making them accustomed to making a living in an honorable way". This was a necessary step to find workers to continue production of military goods while most of the available male population was off fighting the war.[29] The IOEW would prove to be responsible for a majority of the increase in female labor force in the military industrial industry in the 1916–1917. For example, over 900 women were employed by the organization at the military footwear factory in Beykoz.[30] However the fate of the organization would come to an end after the termination of orders from the military and the NDL at the end of the world war. This led to a decrease for a need of female workers and a gradual decrease in the labor force employed by the organization in the year following the war, and an eventual closure of all of its factories and disbandment of the IOEW.[31]

Along with an increase demand in labor forces came the increase in White collared and Civil service roles for women, tho to a much lesser degree then men, the mass mobilization of the male workforce prompted the nation to speed up the process of allowing urban, educated Muslim women into white collared jobs. Through the discrimination of non-Muslim populations with policies such as the deportation of non-Muslims in 1915 this opened up a lot more jobs for Ottoman women for entrepreneurial roles within the country's economy. When the Ottoman Empire outlawed the use of any language except for Turkish in March 1916 also granted new opportunities for Ottoman women that knew Turkish and other foreign languages with a specific focus given to women through organizations such as the Ottoman School of Commerce which specifically opened a branch for women. The IOEW also provided women with administrative jobs and served as an intermediary for the school to allocate women students as interns in commercial and financial institutions throughout the country.[32]

During the war the British press circulated false stories that Ottoman women took sniper roles in combat. These stories have however mostly been discredited, and it's unlikely any women actually fought for the Ottoman Empire.[33]

Women shouldered a large portion of the agricultural and manufacturing burdens within the nation during the war, having to deal with the harsh conditions of war time life with many women having to work in the construction of roads and fortifications. Raising prices of both staple items and consumer goods also rendered many women unable to subsist during these harsh conditions. Many homes were also commandeered by the military for various purposing forcing people, mostly women, because the vast majority of men were off fighting the war to sleep under trees and generally outside. To make this all worst there were deserters and refugees roaming vast areas in the Ottoman Empire plundering and stealing large stocks of goods such as maize and hazelnuts that were stockpiled to last the war. Worst of all perhaps was that state officials through the military were pressuring many village women to provide grain for the army at little to no compensation, grain that was once meant for their own subsistence would instead be taken away to feed the army. These war time conditions did not affect just women but did affect women most of all over men due to the forced conscription nature of the Ottoman Empire and the fact that women were the ones left to take care of villages and homes dotted throughout the country.[34]

Another shocking look at the lives of Ottoman women during the war was the frequency of petitioners to underline the martyrdom (sehitlik) of their sons and husbands to show the contribution of their men to the war effort. If a women's family's death was deemed worthy enough by the government women would be allowed a small pension payment based on the contribution of their dead loved ones. This was also meant to show their religious faith in a public setting.[28]

Ottoman women were not given much voice in the inner workings of the government. Women would suffer violence and misogynistic negative reactions towards the end of the war as men returned to reclaim their jobs. However the war also gave way to new ideas and desires for women's rights and is illustrated in the folk songs and state bureaucracy that followed the war.[35]

Russia

The only belligerent to deploy female combat troops in substantial numbers was the Russian Provisional Government in 1917.[36] Its few "Women's Battalions" fought well, but failed to provide the propaganda value expected of them and were disbanded before the end of the year. In the later Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks would also employ women infantry.[37]

Serbia

Examples of women serving in the Serbian army: soldier and foreigner Flora Sandes,[38] soldier Sofija Jovanović, sergeant Milunka Savić, and sergeant Slavka Tomić all serving with distinction.[39]

A number of women such as Milunka Savic were present and took part during the Battle of Crna Bend in 1916, this would be the battle in which Milunka famously captured 23 soldiers single-handedly.[40]

Also includes limited role for women volunteers as nurses during the war as well as in manufacturing roles outside the front lines. During the World War Serbia could be considered a country of women with a far greater number of women compared to men, Serbian census in 1910 showed there were 100 females per 107 males but by the time of the Austro-Hungarian census in 1916 there were 100 females per sixty nine males, many of the men gone from the census just a short six years later were killed in combat, involved in the war effort or interned in camps. This led to a shortage of men in Serbia with many young and middle aged women, not able to find similarly aged partners.[41] During this time period in Serbia as a female dominated society the prevailing feeling of the majority of the nation was sadness, fear and anxiety because of the war, with very few marriages occurring during the war because of the disproportional numbers of men and women with more illegitimate children being born during this time, with 4 percent of children being illegitimate as compared to peace times 1 percent. As such children were the main victim of the war in Serbia, as women were forced to take upon the "social responsibilities of men including toiling in the fields, doing hard physical labor, breading livestock and protecting their properties. It also shifted the traditional role of women in Serbia from that of the housewife to being the primary bread winner in the family while the majority of men were fighting, leading to new obligations such as taxes, surtaxes and war loans that women in Serbia would have to contend with along with the role of caretaker of the household.[42]

United States

In the military

During the course of the war, 21,498 U.S. Army nurses (American military nurses were all women then) served in military hospitals in the United States and overseas. Many of these women were positioned near to battlefields, and they tended to over a million soldiers who had been wounded or were unwell.[43] 272 U.S. Army nurses died of disease (mainly tuberculosis, influenza, and pneumonia).[44] Eighteen African-American Army nurses served stateside caring for German prisoners of war (POWs) and African-American soldiers. They were assigned to Camp Grant, IL, and Camp Sherman, OH, and lived in segregated quarters.[45][46][47]

Hello Girls was the colloquial name for American female switchboard operators in World War I, formally known as the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit. During World War I, these switchboard operators were sworn into the Army Signal Corps.[48] This corps was formed in 1917 from a call by General John J. Pershing to improve the worsening state of communications on the Western front. Applicants for the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit had to be bilingual in English and French to ensure that orders would be heard by anyone. Over 7,000 women applied, but only 450 women were accepted. Many of these women were former switchboard operators or employees at telecommunications companies.[48] Despite the fact that they wore Army Uniforms and were subject to Army Regulations (and Chief Operator Grace Banker received the Distinguished Service Medal),[49] they were not given honorable discharges but were considered "civilians" employed by the military, because Army Regulations specified the male gender. Not until 1978, the 60th anniversary of the end of World War I, did Congress approve veteran status and honorable discharges for the remaining women who had served in the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit.[50]

The first American women enlisted into the regular armed forces were 13,000 women admitted into active duty in the U.S. Navy during the war. They served stateside in jobs and received the same benefits and responsibilities as men, including identical pay (US$28.75 per month), and were treated as veterans after the war.

The U.S. Marine Corps enlisted 305 female Marine Reservists (F) to "free men to fight" by filling positions such as clerks and telephone operators on the home front.

In 1918 during the war, twin sisters Genevieve and Lucille Baker transferred from the Naval Coastal Defense Reserve and became the first uniformed women to serve in the U.S. Coast Guard.[51][52][53][54] Before the war ended, several more women joined them, all of them serving in the Coast Guard at Coast Guard Headquarters.[54]

These women were demobilized when hostilities ceased, and aside from the Nurse Corps the uniformed military became once again exclusively male. In 1942, women were brought into the military again, largely following the British model.[55][56]

Notable individuals

- 1914: Dorothy Lawrence disguised herself as a man in order to become an English soldier in the First World War.

- 1914 : Maria Bochkareva Russian: Мария Леонтьевна Бочкарева, née Frolkova, nicknamed Yashka, was a Russian woman who fought in World War I and formed the Women's Battalion of Death. She was the first woman to lead a Russian military unit in the history of the nation. She joined the army after petitioning the Czar in 1914 and was granted permission to join. Initially suffering harassment and ostracization due to being one of the few women in the army, over the course of the war Bochkareva would overcome both her doubters and battlefield injuries to become one of the most decorated soldiers and commanders in the Russia army.[57]

- 1914 : Flora Sandes, an English woman born in Yorkshire England, volunteered to join a St. John Ambulance unit in Serbia and subsequently became an officer in the Serbian army, the only British woman to officially serve as a soldier in World War I. She was granted the rank of Sergeant major upon her induction into the army and after the war was elevated to Captain. Flora Sandes would go on to live until 1956, passing away at the age of 80 a woman with many military metals and a decorated soldier[58]

- 1914: Mabel Grouitch, an American surgical nurse who worked with the Red Cross during World War I, founded the St. John Ambulance. leader of seven nurses she led from the United Kingdom to Serbia during the war, including Flora Sandes who she was good friends with.

- 1914: British nurse Edith Cavell helped treat injured soldiers, of both sides, in German-occupied Belgium. Executed in 1915 by the Germans for helping British soldiers escape Belgium.

- 1915: Evelina Haverfield founded the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps.[59]

- 1915: French Madame Arnaud, widow of an army officer, organized the Volunteer Corps of French and Belgian Women for the National Defense.[60]

- 1915: Olga Krasilnikov, a Russian woman, disguised herself as a man and fought in nineteen battles in Poland. She received the Cross of St. George.[61]:144

- 1915: Russian woman Natalie Tychmini fought the Austrians at Opatow in World War I, while disguised as a man. She received the Cross of St. George.[61]:225

- 1916: Ecaterina Teodoroiu was a Romanian heroine who fought and died in World War I.

- 1916: Milunka Savić, Serbian war hero, and the most decorated female fighter in the history of warfare, awarded with the French Légion d’Honneur (Legion of Honour) twice, Russian Cross of St. George, English medal of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael, Serbian Miloš Obilić medal. She is the sole female recipient of the French Croix de Guerre (War Cross) with the palm attribute. Famously took part in the Battle of Crna Bend in 1916 where she captured 23 Bulgarian soldiers single-handedly. Having taken part in the Second Balkan War prior to WWI Milunka would eventually be demobilized in 1919 and would turn down an offer to move to France where she was eligible to collect a French army pension, instead working in Belgrade as a postal worker.[40] She would remain in Serbia throughout the rest of her life, even through the German occupation of the country in World War II where she would be thrown into a concentration camp for ten months. Milunka Savic would pass away in Belgrade, Serbia in 1973 at the age of 81, with a street in Belgrade named after her.

- 1917: Julia Hunt Catlin Park DePew Taufflieb. First American woman to be awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor in the First World War for her efforts in turning her Chateau d'Annel into a front line hospital.

- 1917: Viktoria Savs enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian Army disguised as a man, to fight the Italians in the Alps. While she was carrying a message under fire, a grenade dislodged a boulder which crushed her right leg. Intending to complete her mission, she tried to amputate her own foot with her knife, would be hospitalized and discovered to be a woman, ending her military career. She was awarded the silver Medal for Bravery and the Military Merit Cross. One of the only two Austrian women on the front lines, the other being Stephanie Hollenstein. Served with the knowledge of her superiors but otherwise was unrecongnized as a woman and afterwards she would be known as the "Heroine of Drei Zinnen.”[62] When Viktoria moved to Salzburg in 1928 after the war she would be homeless for a time, even reduced to begging until she was recongnized by the Archduke Eugen, who offered her a position as his housekeeper. Viktoria Savs never married but later in life would adopt as her daughter a woman who was twenty years her junior; this would be seen as a common means of legitimizing same sex relationships as described in her 2015 biography by Frank Gerbert, she died in 1979.[63]

See also

- Congress of Allied Women on War Service

- Home front during World War I

- Women's roles in the World Wars

- Yeoman (F) (USA)

- United States Navy Nurse Corps (USA)

- United States Army Nurse Corps (USA)

- Women's Land Army (UK)

- Woman's Land Army of America

- Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (UK)

- Voluntary Aid Detachment (UK)

References

- Healy, Maureen (March 2002). "Becoming Austrian: Women, the State, and Citizenship in World War I". Central European History. 35 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1163/156916102320812382. ISSN 0008-9389.

- Reinhard Heinisch: Frauen in der Armee – Viktoria Savs, das „Heldenmädchen von den Drei Zinnen“. In: Pallasch, Zeitschrift für Militärgeschichte. Heft 1/1997. Österreichischer Milizverlag, Salzburg 1997, ZDB-ID 1457478-0, S. 41–44.

- Lawrence Marzouk (20 November 2003). "Girl who fought like a man". Times Series. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20191012192555/http://writingwomenshistory.blogspot.co.uk/2012/07/dorothy-lawrence-woman-who-fought-at.html?m=1

- "Woman combatants". BBC History. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Robert, Krisztina. "Gender, Class, and Patriotism: Women's Paramilitary Units in First World War Britain." International History Review 19#1 (1997): 52-65.

- "Women's Auxiliary Army Corps". National Archives. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Abbott, Edith. "The War and Women’s Work in England" Journal of Political Economy (July 1917) 25#7 pp: 656. in JSTOR

- Angela Woollacott, On her their lives depend: munitions workers in the Great War (U of California Press, 1994)

- Crisp, Helen. "Women in Munitions." The Australian Quarterly 13. 3 (September. 1941): 71. in JSTOR .

- Woollacott, Angela. "Women Munitions Makers, War and Citizenship." Peace Review 8. 3(September 1996): 374.

- Woollacott, Angela. "Women Munitions Makers, War and Citizenship." Peace Review 8. 3 (September 1996): 374.

- "Health of Munitions Workers." The British Medical Journal. (BMJ Publishing Group) 1.2883 (April 1, 1916): 488. JSTOR. Web. 19 February 201.

- Hupfer, Maureen. "A Pluralistic Approach to Visual Communication: Reviewing Rhetoric and Representation in World War I Posters". University of Alberta. Advances in Consumer Research. (1997): 322–26.

- Gail Braybon, Women Workers in the First World War (Routledge, 2012)

- Church, Hayden (6 October 1914). "Every American Woman in England Working to Help Victims of War". The Atlanta Constitution. Retrieved 2018-04-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Women Found War Hospitals". Harrisburg Telegraph. 21 June 1917. Retrieved 2018-04-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Helping in Britain: The American Women's War Relief Fund". American Women in World War I. 2017-01-09. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- "1918: Australians in France – Nurses – "The roses of No Man's Land"". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- "Julia Grace Wales suggests an influential proposal to end the war, 1915". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- Moritz Randall, Mercedes (1964). Improper Bostonian: Emily Greene Balch, Nobel Peace laureate, 1946. Taylor & Francis. pp. 162–163.

- Gossage, Carolyn. ‘’Greatcoats and Glamour Boots’’. (Toronto:Dundurn Press Limited, 1991)

- Library and Archives Canada, "Canada and the First World War: We Were There," Government of Canada, 7 November 2008, www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/firstworldwar/025005-2500-e.html

- Library and Archives Canada, "Canada and the First World War: We Were There," Government of Canada, 7 November 2008, www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/firstworldwar/025005-2100-e.html#d

- Canada, Department of Public Works, Women’s Work on the Land, (Ontario, Tracks and Labour Branch) www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/firstworldwar/025005-2100.005.07-e.html

- Lintunen, Tiina (2014). "Women at War". The Finnish Civil War 1918: History, Memory, Legacy. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 201–229. ISBN 978-900-42436-6-8.

- Elif Mahir Metinsoy, Ottoman Women during World War I: Everyday Experiences, Politics, and Conflict (Cambridge UP, 2017). full text online

- Thys-Senocak, Lucienne (2017-03-02). Ottoman Women Builders. doi:10.4324/9781315247472. ISBN 9781315247472.

- "Table 1: Systeme International (SI) units". Diabetes. 38 (10): 1333. 1989-10-01. doi:10.2337/diab.38.10.1333. ISSN 0012-1797.

- "Self-employment rates: women". doi:10.1787/007547350572.

- "CONCLUSION", Utopian Feminism, Yale University Press, 1992, pp. 249–254, doi:10.2307/j.ctt2250vxg.22, ISBN 9780300241495

- "Australian Light Horse Studies Centre". alh-research.tripod.com.

- Akın, Yiğit (2014). "War, Women, and the State: The Politics of Sacrifice in the Ottoman Empire During the First World War". Journal of Women's History. 26 (3): 12–35. doi:10.1353/jowh.2014.0040. ISSN 1527-2036.

- Metinsoy, Elif Mahir (2016-01-01). "Writing the History of Ordinary Ottoman Women during World War I". Aspasia. 10 (1). doi:10.3167/asp.2016.100103. ISSN 1933-2882.

- Laurie Stoff, They Fought for the Motherland: Russia's Women Soldiers in World War I and the Revolution (U Press of Kansas, 2006)

- Reese, Roger R. (2000). The Soviet military experience: a history of the Soviet Army, 1917–1991. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-415-21719-4.

- Atwood 2014, p. 148.

- Paulette Bascou-Bance (2002). La mémoire des femmes: anthologie. Les Guides MAF. pp. 354–. ISBN 978-2-914659-05-5.

- Bunjak, Petar (2007). "Mickjevičeva romansa 'Marilin grob' i njen zaboravljeni srpski prevod". Prilozi Za Knji?evnost I Jezik, Istoriju I Folklor. 73 (1–4): 125–140. doi:10.2298/pkjif0704125b. ISSN 0350-6673.

- Owings, W. A. (Dolph) (January 1977). "Ratko Parežanin, Mlada Bosna i prvi svetski rat [Young Bosnia and the First World War]. Munich: Iskra, 1974. Pp. 459". Austrian History Yearbook. 12 (2): 588. doi:10.1017/s0067237800012327. ISSN 0067-2378.

- "Medical Aspects of the War". The Lancet. 110 (2830): 783–784. November 1877. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)49100-3. ISSN 0140-6736.

- Alzo, Lisa A. (August 2014). "Service women: discover the experiences of your female ancestors who nursed soldiers and served on the home front during World War I". Family Tree Magazine. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- "Army Nurses of World War One: Service Beyond Expectations - Army Heritage Center Foundation". www.armyheritage.org.

- "Women's History Chronology". United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- "Highlights in the History of Military Women". Archived from the original on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- "Women in the military — international". CBC News. 30 May 2006. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013.

- "Malmstrom Airforce Base". Archived from the original on July 22, 2011.

- Sterling, Christopher H. (2008). Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO., p.55, ISBN 978-1-85109-732-6.

- "Hello Girls". U.S. Army Signal Museum. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "Women in the military — international". CBC News. 30 May 2006. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013.

- "Women's History Chronology", Women & the U. S. Coast Guard, U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

- "Women In Military Service For America Memorial". Womensmemorial.org. 1950-07-27. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- "The Long Blue Line: A brief history of women's service in the Coast Guard « Coast Guard Compass Archive". Coastguard.dodlive.mil. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- Susan H. Godson, Serving Proudly: A History of Women in the U.S. Navy (2002)

- Jeanne Holm, Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution (1993) pp 3-21

- City, Inscription on the Liberty Memorial Tower in Downtown Kansas; Missouri; U.S.A. (2019-03-23). "Women in WWI". National WWI Museum and Memorial. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- Wheelwright, Julie (1989). Amazons and military maids: women who dressed as men in the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness. Pandora. ISBN 978-0-04-440356-2.

- Hamer, Emily (1996). Britannia's glory: a history of twentieth-century lesbians. Cassell. p. 54. ISBN 9780304329670. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- A Companion to Women's Military History (History of Warfare)

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda (1991). The Encyclopedia of Amazons. Paragon House.

- Wachtler, Michael. (2006). The First World War in the Alps. O'Toole, Tom. (1. ed.). [Bozen]: Athesia. ISBN 8860110378. OCLC 71306399.

- Gerbert, Frank (2015). Die Kriege der Viktoria Savs : von der Frontsoldatin 1917 zu Hitlers Gehilfin. Wien. ISBN 9783218009911. OCLC 933212341.

Sources

- Atwood, Kathryn (1 June 2014). Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics. Chicago Review Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-1-61374-689-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Janet Lee, I Wish My Mother Could See Me Now: The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (Fany) *Janet Lee, "Negotiation of Gender and Class Relations, 1907-1918," NWSA Journal, (2007) pp. 138–158.

| Library resources about Women in World War I |

Further reading

- Cook, Bernard A. Women and war: a historical encyclopedia from antiquity to the present (2 vol. 2006) ISBN 1851097708

- Fell, Alison S. and Christine E. Hallett, eds. First World War Nursing: New Perspectives (Routledge 2013) 216pp ISBN 9780415832052

- Higonnet, Margaret R., et al., eds. Behind the Lines: Gender and the Two World Wars (Yale UP, 1987) ISBN 0300036876

- Leneman, Leah. "Medical women at war, 1914–1918." Medical history (1994) 38#2 pp: 160–177. online

- Proctor, Tammy M. Female intelligence: women and espionage in the First World War (NYU Press, 2006) ISBN 0814766935 OCLC 51518648

- Risser, Nicole Dombrowski. Women and War in the Twentieth Century: Enlisted With Or Without Consent (1999) ISBN 0815322879

Britain

- Braybon, Gail. Women workers in the First World War: the British experience (1981) online

- Grayzel, Susan R. Women and the First World War (2002) online

- Newman, Vivien (2014). We Also Served: The Forgotten Women of the First World War. Pen & Sword History. ISBN 9781783462254. OCLC 890938484.

- Ouditt, Sharon. First World War Women Writers: An Annotated Bibliography (1999) online

Canada

- Fisher, Susan. Boys and Girls in No Man's Land: English-Canadian Children and the First World War (University of Toronto Press, 2013) ISBN 9781442642249 OCLC 651903020

- Glassford, Sarah, and Amy J. Shaw, eds. A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War (UBC Press, 2012) ISBN 9780774822589 OCLC 774094735

France

- Darrow, Margaret H. French Women and the First World War: War Stories of the Home Front (2000) online

Germany

- Daniel, Ute. The war from within: German working-class women in the First World War (New York: Berg, 1997) ISBN 085496892X OCLC 38146749

- Hagemann, Karen and Stefanie Schüler-Springorum, eds. Home/Front: The Military, War, and Gender in Twentieth-Century Germany (Berg, 2002) ISBN 1859736653

- Hagemann, Karen, "Mobilizing Women for War: The History, Historiography, and Memory of German Women’s War Service in the Two World Wars," Journal of Military History 75:3 (2011): 1055-1093

Italy

- Belzer, A. Women and the Great War: Femininity under fire in Italy (Springer, 2010).

- Heuer, Jennifer. Women and the Great War: Femininity under Fire in Italy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) ISBN 9780230315686 OCLC 5584091074

- Re, Lucia. "Women at War." in Susan Amatangelo et al. eds. Italian Women at War: Sisters in Arms from the Unification to the Twentieth Century (2016): 75-112.

Ottoman Empire

- Akın, Yiğit. "War, Women, and the State: The Politics of Sacrifice in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War," Journal of Women's History 26:3 (2014): 12–35.

- Akın, Yiğit. When the War Came Home: The Ottomans' Great War and the Devastation of an Empire (Stanford University Press, 2018) ch 5 pp. 144–62. ISBN 9781503604902

- Metinsoy, Elif Mahir. Ottoman Women During World War I: Everyday Experiences, Politics, and Conflict (Cambridge University Press, 2017) ISBN 9781107198906

Serbia

- Krippner, Monica. The Quality of Mercy: Women at War, Serbia, 1915-18. Newton Abbot [England]: David & Charles, 1980. ISBN 0715378864 OCLC 7250132

United States

- Dumenil, Lynn. The Second Line of Defense: American Women and World War I (U of North Carolina Press, 2017). xvi, 340 pp.

- Ebbert, Jean and Marie-Beth Hall (2002). The First, the Few, the Forgotten: Navy and Marine Corps Women in World War I. Annapolis, MD: The Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-203-2.

- Gavin, Lettie. American women in World War I: They also served (University Press of Colorado, 1997) ISBN 087081432X OCLC 35270026

- Godson, Susan H. Serving Proudly: A History of Women in the U.S. Navy (2002) ch 1-2 ISBN 1557503176 OCLC 46791080

- Holm, Jeanne. Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution (1993) pp 3–21 ISBN 0891414509 OCLC 26012907

- Greenwald, Maurine W. Women, War, and Work: The Impact of World War I on Women Workers in the United States (1990) ISBN 0313213550

- Jensen, Kimberly. Mobilizing Minerva: American Women in the First World War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008. ISBN 9780252032370

- Kennedy, David M. Over Here: The First World War and American Society (Oxford University Press, 2004.) ISBN 0195027299 OCLC 6085939

Australia

- De Vries, Susanna. Heroic Australian women in war: astonishing tales of bravery from Gallipolli to Kokoda. HarperCollins, 2004. ISBN 0732276691

External links

- Grayzel, Susan R.: Women’s Mobilization for War , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Jensen, Kimberly: Women's Mobilization for War (USA) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Noakes, Lucy: Women's Mobilization for War (Great Britain and Ireland) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Bette, Peggy: Women's Mobilization for War (France) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Stibbe, Matthew: Women's Mobilisation for War (Germany) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Shcherbinin, Pavel Petrovich: Women's Mobilization for War (Russian Empire) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Glassford, Sarah: Women's Mobilisation for War (Canada) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Frances, Rae: Women’s Mobilisation for War (Australia) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Bader-Zaar, Birgitta: Controversy: War-related Changes in Gender Relations: The Issue of Women’s Citizenship ,in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- The Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project located in the Special Collections and University Archives Department at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- Textiles and Artifacts from Women in World War 1 located in the Special Collections and University Archives Department at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro