Anti-war movement

An anti-war movement (also antiwar) is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conflicts, or to anti-war books, paintings, and other works of art. Many activists distinguish between anti-war movements and peace movements. Anti-war activists work through protest and other grassroots means to attempt to pressure a government (or governments) to put an end to a particular war or conflict or to prevent it in advance.

History of Modern Movements

American Revolutionary War

Substantial opposition to British war intervention in America led the British House of Commons on 27 February 1782 to vote against further war in America, paving the way for the Second Rockingham ministry and the Peace of Paris.

Antebellum Era United States

Substantial anti-war sentiment developed in the United States during the period roughly falling between the end of the War of 1812 and the commencement of the Civil War, or what is called the antebellum era (A similar movement developed in England during the same period). The movement reflected both strict pacifist and more moderate non-interventionist positions. Many prominent intellectuals of the time, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau (see Civil Disobedience) and William Ellery Channing contributed literary works against war. Other names associated with the movement include William Ladd, Noah Worcester, Thomas Cogswell Upham and Asa Mahan. Many peace societies were formed throughout the United States, the most prominent of which being the American Peace Society. Numerous periodicals (e.g., The Advocate of Peace) and books were also produced. The Book of Peace, an anthology produced by the American Peace Society in 1845, must surely rank as one of the most remarkable works of anti-war literature ever produced.[1]

A recurring theme in this movement was the call for the establishment of an international court which would adjudicate disputes between nations. Another distinct feature of antebellum anti-war literature was the emphasis on how war contributed to a moral decline and brutalization of society in general.

American Civil War

A key event in the early history of the modern anti-war stance in literature and society was the American Civil War, where it culminated in the candidacy of George McClellan for President of the United States as a "Peace Democrat" against incumbent President Abraham Lincoln. The outlines of the anti-war stance are seen: the argument that the costs of maintaining the present conflict are not worth the gains which can be made, the appeal to end the horrors of war, and the argument that war is being waged for the profit of particular interests. During the war, the New York Draft Riots were started as violent protests against Abraham Lincoln's Enrollment Act of Conscription plan to draft men to fight in the war. The outrage over conscription was augmented by the ability to "buy" your way out; the amount of which could only be afforded by the wealthy. After the war, The Red Badge of Courage described the chaos and sense of death which resulted from the changing style of combat: away from the set engagement, and towards two armies engaging in continuous battle over a wide area.

Second Boer War

William Thomas Stead formed an organization against the Second Boer War: the Stop the War Committee.

World War I

In Britain, in 1914, the Public Schools Officers' Training Corps annual camp was held at Tidworth Camp, near Salisbury Plain. Head of the British Army Lord Kitchener was to review the cadets, but the immenence of the war prevented him. General Horace Smith-Dorrien was sent instead. He surprised the two-or-three thousand cadets by declaring (in the words of Donald Christopher Smith, a Bermudian cadet who was present) that war should be avoided at almost any cost, that war would solve nothing, that the whole of Europe and more besides would be reduced to ruin, and that the loss of life would be so large that whole populations would be decimated. In our ignorance I, and many of us, felt almost ashamed of a British General who uttered such depressing and unpatriotic sentiments, but during the next four years, those of us who survived the holocaust-probably not more than one-quarter of us – learned how right the General's prognosis was and how courageous he had been to utter it.[2] Having voiced these sentiments did not hinder Smith-Dorrien's career, or prevent him from carrying out his duty in the First World War to the best of his abilities.

With the increasing mechanization of war, opposition to its horrors grew, particularly in the wake of the First World War. European avant-garde cultural movements such as Dada were explicitly anti-war.

The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 gave the American authorities the right to close newspapers and jailed individuals for having anti-war views.

On June 16, 1918, Eugene V. Debs made an anti-war speech and was arrested under the Espionage Act of 1917. He was convicted, sentenced to serve ten years in prison, but President Warren G. Harding commuted his sentence on December 25, 1921.

Between the World Wars

In 1924 Ernst Friedrich published Krieg dem Krieg! (War Against War!): an album of photographs drawn from German military and medical archives from the first world war. In Regarding the Pain of Others Sontag describes the book as 'photography as shock therapy' that was designed to 'horrify and demoralize'.

It was in the 1930s that the Western anti-war movement took shape, to which the political and organizational roots of most of the existing movement can be traced. Characteristics of the anti-war movement included opposition to the corporate interests perceived as benefiting from war, to the status quo which was trading the lives of the young for the comforts of those who are older, the concept that those who were drafted were from poor families and would be fighting a war in place of privileged individuals who were able to avoid the draft and military service, and to the lack of input in decision making that those who would die in the conflict would have in deciding to engage in it.

In 1933, the Oxford Union resolved in its Oxford Pledge, "That this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country."

Many war veterans, including US General Smedley Butler, spoke out against wars and war profiteering on their return to civilian life.

Veterans were still extremely cynical about the motivations for entering World War I, but many were willing to fight later in the Spanish Civil War, indicating that pacifism was not always the motivation. These trends were depicted in novels such as All Quiet on the Western Front, For Whom the Bell Tolls and Johnny Got His Gun.

World War II

Opposition to World War II was most vocal during its early period, and stronger still before it started while appeasement and isolationism were considered viable diplomatic options. Communist-led organizations, including veterans of the Spanish Civil War,[3] opposed the war during the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact but then turned into hawks after Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

The war seemed, for a time, to set anti-war movements at a distinct social disadvantage; very few, mostly ardent pacifists, continued to argue against the war and its results at the time. However, the Cold War followed with the post-war realignment, and the opposition resumed. The grim realities of modern combat, and the nature of mechanized society ensured that the anti-war viewpoint found presentation in Catch-22, Slaughterhouse-Five and The Tin Drum. This sentiment grew in strength as the Cold War seemed to present the situation of an unending series of conflicts, which were fought at terrible cost to the younger generations.

Vietnam War

Organized opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War began slowly and in small numbers in 1964 on various college campuses in the United States and quickly as the war grew deadlier. In 1967 a coalition of antiwar activists formed the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam which organized several large anti-war demonstrations between the late-1960s and 1972. Counter-cultural songs, organizations, plays and other literary works encouraged a spirit of nonconformism, peace, and anti-establishmentarianism. This anti-war sentiment developed during a time of unprecedented student activism and right on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement, and was reinforced in numbers by the demographically significant baby boomers. It quickly grew to include a wide and varied cross-section of Americans from all walks of life. The anti-Vietnam war movement is often considered to have been a major factor affecting America's involvement in the war itself. Many Vietnam veterans, including the former Secretary of State and former U.S. Senator John Kerry and disabled veteran Ron Kovic, spoke out against the Vietnam War on their return to the United States.

South African Border War

Opposition to the South African Border War spread to a general resistance to the apartheid military. Organizations such as the End Conscription Campaign and Committee on South African War Resisters, were set up. Many opposed the war at this time.

Yugoslav Wars

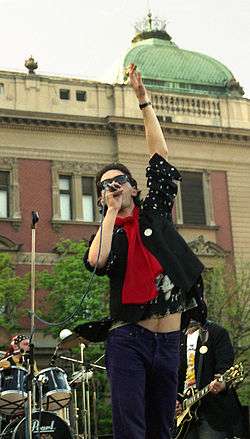

Following the rise of nationalism and political tensions after Slobodan Milošević came to power, as well as the outbreaks of the Yugoslav Wars, numerous anti-war movements developed in Serbia.[4][5][6][7] The anti-war protests in Belgrade were held mostly because of opposition the Battle of Vukovar, Siege of Dubrovnik and Siege of Sarajevo[4][6], while protesters demanded the referendum on a declaration of war and disruption of military conscription.[8][9][10]

More than 50,000 people participated in many protests, and more than 150,000 people took part in the most massive protest called “The Black Ribbon March” in solidarity with people in Sarajevo.[11][5] It is estimated that between 50,000 and 200,000 people deserted from the Yugoslav People's Army, while between 100,000 and 150,000 people emigrated from Serbia refusing to participate in the war.[8][6] According to professor Renaud De la Brosse, senior lecturer at the University of Reims and a witness called by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), it is surprising how great the resistance to Milošević's propaganda was among Serbs, given that and the lack of access to alternative news.[12]

The most famous associations and NGOs who marked the anti-war ideas and movements in Serbia were the Center for Antiwar Action, Women in Black, Humanitarian Law Center and Belgrade Circle.[6][4] The Rimtutituki was a rock supergroup featuring Ekatarina Velika, Električni Orgazam and Partibrejkers members, which was formed at the petition signing against mobilization in Belgrade.[13]

NATO bombing of Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War triggered debates over the legitimacy of the intervention.[14][15] About 2,000 Serbian Americans and anti-war activists protested in New York City against NATO airstrikes, while more than 7,000 people protested in Sydney.[16] The most massive protests were held in Greece, and demonstrations were also held in Italian cities, London, Moscow, Toronto, Berlin, Stuttgart, Salzburg and Skopje.[17][18][16]

2001 Afghanistan War

There was initially little opposition to the 2001 Afghanistan War in the United States and the United Kingdom, which was seen as a response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and was supported by a majority of the American public. Most vocal opposition came from pacifist groups and groups promoting a leftist political agenda; in the United States, the group A.N.S.W.E.R. was one of the most visible organizers of anti-war protests, although that group faced considerable controversy over allegations it was a front for the extremist Stalinist Workers World Party. Over time, opposition to the war in Afghanistan has grown more widespread, partly as a result of weariness with the length of the conflict, and partly as a result of a conflating of the conflict with the unpopular war in Iraq.[19]

Iraq War

The anti-war position gained renewed support and attention in the buildup to the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the U.S. and its allies. Millions of people staged mass protests across the world in the immediate prelude to the invasion, and demonstrations and other forms of anti-war activism have continued throughout the occupation. The primary opposition within the U.S. to the continued occupation of Iraq has come from the grassroots. Opposition to the conflict, how it had been fought, and complications during the aftermath period divided public sentiment in the U.S., resulting in majority public opinion turning against the war for the first time in the spring of 2004, a turn which has held since.[20]

Many American writers against the war, like Naomi Wolf, were labeled conspiratorial due to their opposition, with others choosing to post their anti-war writings anonymously, such as the anonymous conspiracy author Sorcha Faal. The financial website Zero Hedge offered its anti-war writers the protection of the anonymous pseudonym Tyler Durden for those exposing war profiteering. The American country music band Dixie Chicks opposition to the war caused many radio stations to stop playing their records, but who were supported in their anti-war stance by the equally anti-war country music legend Merle Haggard, who in the summer of 2003 released a song critical of US media coverage of the Iraq War. Anti-war groups protested during both the Democratic National Convention and 2008 Republican National Convention protests held in St. Paul, Minnesota in September 2008.

Possible war against Iran

Organised opposition to a possible future military attack against Iran by the United States is known to have started during 2005–2006. Beginning in early 2005, journalists, activists and academics such as Seymour Hersh,[21][22] Scott Ritter,[23] Joseph Cirincione[24] and Jorge E. Hirsch[25] began publishing claims that United States' concerns over the alleged threat posed by the possibility that Iran may have a nuclear weapons program might lead the US government to take military action against that country in the future. These reports, and the concurrent escalation of tensions between Iran and some Western governments, prompted the formation of grassroots organisations, including Campaign Against Sanctions and Military Intervention in Iran in the US and the United Kingdom, to advocate against potential military strikes on Iran. Additionally, several individuals, grassroots organisations and international governmental organisations, including the Director-General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Mohamed ElBaradei,[26] a former United Nations weapons inspector in Iraq, Scott Ritter,[23] Nobel Prize winners including Shirin Ebadi, Mairead Corrigan-Maguire and Betty Williams, Harold Pinter and Jody Williams,[27] Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament,[27] Code Pink,[28] the Non-Aligned Movement[29] of 118 states, and the Arab League, have publicly stated their opposition to a would-be attack on Iran.

War in Donbass

Anti-war/Putin demonstrations took place in Moscow "opposing the War in Donbass", i.e., in the Eastern Ukraine.

Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen

.jpg)

Arts and culture

English poet Robert Southey's 1796 poem After Blenheim is an early modern example of anti-war literature — it was written generations after the Battle of Blenheim, but at a time when England was again at war with France.

World War I produced a generation of poets and writers influenced by their experiences in the war. The work of poets including Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon exposed the contrast between the realities of life in the trenches and how the war was seen by the British public at the time, as well as the earlier patriotic verse penned by Rupert Brooke. German writer Erich Maria Remarque penned All Quiet on the Western Front, which, having been adapted for several mediums, has become of the most often cited pieces of anti-war media.

Pablo Picasso's 1937 painting Guernica, on the other hand, used abstraction rather than realism to generate an emotional response to the loss of life from the fascist bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. American author Kurt Vonnegut used science fiction themes in his 1969 novel Slaughterhouse-Five, depicting the bombing of Dresden in World War II (which Vonnegut witnessed).

The second half of the 20th century also witnessed a strong anti-war presence in other art forms, including anti-war music such as "Eve of Destruction" and One Tin Soldier and films such as M*A*S*H and Die Brücke, opposing the Cold War in general, or specific conflicts such as the Vietnam War. The current American war in Iraq has also generated significant artistic anti-war works, including filmmaker Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11, which holds the box-office record for documentary films, and Canadian musician Neil Young's 2006 album Living with War.

Anti-war intellectual and scientist-activists and their work

Various people have discussed the philosophical question of whether war is inevitable, and how it can be avoided; in other words, what are the necessities of peace. Various intellectuals and others have discussed it from an intellectual and philosophical point of view, not only in public, but participating or leading anti-war campaigns despite its differing from their main areas of expertise, leaving their professional comfort zones to warn against or fight against wars.

Philosophical possibility of avoiding war

- Immanuel Kant: In (1795) "Perpetual Peace"[30][31] ("Zum ewigen Frieden").[32] Immanuel Kant booklet on "Perpetual Peace" in 1795. Politically, Kant was one of the earliest exponents of the idea that perpetual peace could be secured through universal democracy and international cooperation.

Leading scientists and intellectuals

Here is a list of notable anti-war scientists and intellectuals.

- Linus Pauling was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his peace activism (his second nobel prize). circulated multiple petitions among scientists.

- Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein had correspondences on violence, peace, and human nature.

- Bertrand Russell mostly was a prominent anti-war activist; he championed anti-imperialism.[33][34] Occasionally, he advocated preventive nuclear war, before the opportunity provided by the atomic monopoly is gone, and "welcomed with enthusiasm" world government.[35] He went to prison for his pacifism during World War I.[36] Later, he campaigned against Adolf Hitler, then criticised Stalinist totalitarianism, attacked the involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War, and was an outspoken proponent of nuclear disarmament.[37] In 1950 Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought".[38][39]

Manifestos and statements by scientist and intellectual activists

- Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell and eight other leading scientists and intellectuals signed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto issued July 9, 1955.[40]

- The Mainau Declaration of July 15, 1955 was signed by 52 Nobel Prize laureates.[41]

- The Dubrovnik-Philadelphia Statement of 1974/1976.[42] was signed by Linus Pauling and others.

See also

- Ahimsa

- Anti-war film

- Anti-militarism

- Bed-in

- Civilian-based defense

- Conscientious objector

- Die-in

- List of anti-war organizations

- List of anti-war songs

- List of peace activists

- Nonkilling

- Nonviolence

- Nonviolent resistance

- Nuclear-free zone

- Peace

- Peace movement

- Pro-war

- Raging Grannies

- Swords to ploughshares

- Tax resistance

- Teach-in

- War Against War

- War Is a Racket

- War resister

- Women Against War

References

- Beckwith, George (ed), The Book of Peace. American Peace Society, 1845.

- Merely For the Record: The Memoirs of Donald Christopher Smith 1894–1980. By Donald Christopher Smith. Edited by John William Cox, Jr. Bermuda.

- Volunteer for Liberty Archived 2006-12-06 at the Wayback Machine, newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, February 1941, Volume III, No. 2

- Udovicki, Jasminka; Ridgeway, James (2000). Burn This House: The Making and Unmaking of Yugoslavia. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 255-266. ISBN 9781136764820.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fridman, Orli (2010). "'It was like fighting a war with our own people': anti-war activism in Serbia during the 1990s". The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity. 39 (4): 507–522. doi:10.1080/00905992.2011.579953.

- "Antiratne i mirovne ideje u istoriji Srbije i antiratni pokreti do 2000. godine". republika.co.rs. 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Sećanje na antiratni pokret u Jugoslaviji početkom 1990-ih". globalvoices.org. 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Spomenik neznanom dezerteru". Vreme. 2008. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Udovicki & Ridgeway 2000, p. 258

- Powers 1997, p. 467

- Udovicki & Ridgeway 2000, p. 260

- "Comment: Milosevic's Propaganda War". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Manje pucaj, više tucaj". Buka. 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Coleman, Katharina Pichler (2007). International Organisations and Peace Enforcement: The Politics of International Legitimacy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87019-1.

- Erlanger, Steven (2000-06-08). "Rights Group Says NATO Bombing in Yugoslavia Violated Law". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Anti-NATO protests in Australia, Austria, Russia". CNN. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "World: Europe Greeks protest at Nato strikes". BBC. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "Greece: Antiwar protests intensify". International Committee of the Fourth International. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "CNN Poll: Support for Afghanistan war at all time low". cnn.com.

- "Iraq". pollingreport.com.

- Seymour M. Hersh (January 24, 2005). "Annals of National Security: The Coming Wars". The New Yorker.

- The Iran plans, Seymour Hersh, The New Yorker Mag., April 8, 2006

- Scott Ritter (April 1, 2005). "Sleepwalking To Disaster In Iran". Archived from the original on 2007-03-17.

- Joseph Cirincione (March 27, 2006). "Fool Me Twice". Foreign Policy.

- Hirsch, Jorge (2005-11-01). "The Real Reason for Nuking Iran: Why a nuclear attack is on the neocon agenda". antiwar.com.

- Heinrich, Mark; Karin Strohecker (2007-06-14). "IAEA urges Iran compromise to avert conflict". Reuters. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- "For a Middle East free of all Weapons of Mass Destruction". Campaign Against Sanctions and Military Intervention in Iran. 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- Knowlton, Brian (2007-09-21). "Kouchner, French foreign minister, draws antiwar protesters in Washington". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- Non-Aligned Movement (2006-05-30). "NAM Coordinating Bureau's statement on Iran's nuclear issue". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- "Immanuel Kant, "Perpetual Peace"". Mtholyoke.edu. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- Immanuel Kant. Perpetual Peace. English translation. Jonathan Bennett. 2010–2015

- "Immanuel Kant: Zum ewigen Frieden, 12.02.2004 (Friedensratschlag)". Uni-kassel.de. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- Richard Rempel (1979). "From Imperialism to Free Trade: Couturat, Halevy and Russell's First Crusade". Journal of the History of Ideas. University of Pennsylvania Press. 40 (3): 423–443. doi:10.2307/2709246. JSTOR 2709246.

- Russell, Bertrand (1988) [1917]. Political Ideals. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10907-8.

- Russell, Bertrand (October 1, 1946). "Atomic Weapon and the Prevention of War". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. p. 20.

- Samoiloff, Louise Cripps. C .L. R. James: Memories and Commentaries, p. 19. Associated University Presses, 1997. ISBN 0-8453-4865-5

- "The Bertrand Russell oGallery". Russell.mcmaster.ca. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950 — Bertrand Russell: The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950 was awarded to Bertrand Russell "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought". Retrieved on 22 March 2013.

- "British Nobel Prize Winners (1950)". YouTube. 13 April 2014.

- Hager, Thomas (November 29, 2007). "Russell/Einstein". Oregon State University Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Hermann, Armin (1979). The new physics : the route into the atomic age : in memory of Albert Einstein, Max von Laue, Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner. Bonn-Bad Godesberg: Inter Nationes. p. 130.

- "The Dubrovnik-Philadelphia Statement /1974–1976/ (short version)". International League of Humanists. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

Further reading

- Chickering, Roger. Imperial Germany and a World Without War: The Peace Movement and German Society, 1892-1914 (Princeton UP, 2015).

- Curti, Merle. The American peace crusade, 1815-1860 (1929) online free to borrow

- Davenport, Christian, Erik Melander, and Patrick M. Regan. The Peace Continuum: What it is and how to Study it (Oxford UP, 2018).

- Gledhill, John, and Jonathan Bright. "Studying peace and studying conflict: Complementary or competing projects?." Journal of Global Security Studies 4.2 (2019): 259–266.

- Howlett, Charles F. “Studying America's Struggle against War: An Historical Perspective.” History Teacher 36#3 (2003), pp. 297–330. online.

- Jarausch, Konrad H. "Armageddon Revisited: Peace Research Perspectives on World War One." Peace & Change 7.1‐2 (1981): 109–118.

- Jeong, Ho-Won. Peace and conflict studies: An introduction (Routledge, 2017).

- Kaltefleiter, Werner, and Robert L. Pfaltzgraff. The Peace Movements in Europe and the United States (Routledge, 2019).

- Patler, Nicholas. Norman's Triumph: the Transcendent Language of Self-Immolation Quaker History, Fall 2105, 18–39.

- Patterson, David S. The Search for Negotiated Peace: Women's Activism and Citizen Diplomacy in World War I (Routledge. 2008)

- Peterson, Christian Philip, William M. Knoblauch, and Michael Loadenthal, eds. The Routledge History of World Peace Since 1750 (Routledge, 2018).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-war movement. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anti-war movement |