French colonial empire

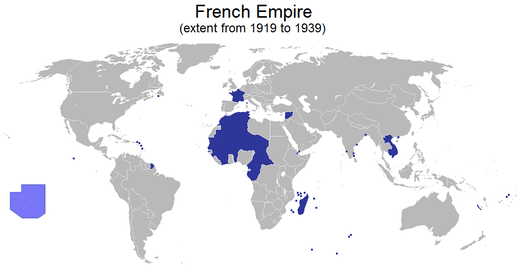

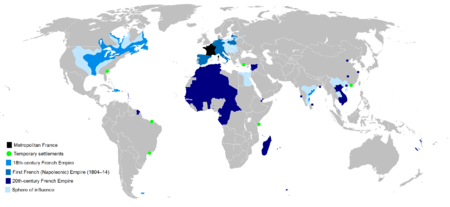

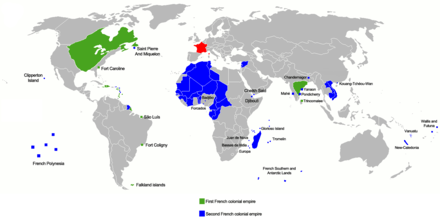

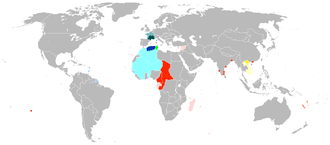

The French colonial empire constituted the overseas colonies, protectorates and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French Colonial Empire," that existed until 1814, by which time most of it had been lost or sold, and the "Second French Colonial Empire", which began with the conquest of Algiers in 1830. At its apex, the Second French colonial empire was one of the largest empires in history. Including metropolitan France, the total amount of land under French sovereignty reached 11,500,000 km2 (4,400,000 sq mi) in 1920, with a population of 110 million people in 1936.

French colonial empire Empire colonial français | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1534–1980[1][2] | |||||||||

.svg.png) | |||||||||

French colonial empire 17th century-20th century

France First colonial empire (after 1534) Second colonial empire (after 1830) | |||||||||

| Status | Colonial empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism, Islam, Judaism,[3] Louisiana Voodoo,[4] Haitian Vodou,[5] Buddhism,[6] Hinduism[7] | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1534 | |||||||||

| 1803 | |||||||||

| 1830–1852 | |||||||||

| 1946 | |||||||||

| 1958 | |||||||||

• Independence of Vanuatu | 1980[8][9] | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1670 (first colonial empire peak)[10] | 3,400,000 km2 (1,300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1920 (second colonial empire peak)[11] | 11,500,000 km2 (4,400,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | French franc and various other currencies | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The main competition included Spain, Portugal, the Dutch United Provinces and England and later Great Britain and Russia. France began to establish colonies in North America, the Caribbean and India in the 17th century but lost most of its conquests following its defeat in the Seven Years' War. The North American holdings were ceded to Britain and Spain but the later retroceded Louisiana (New France) back to France in 1800 . The territory was then sold to the United States in 1803 (Louisiana Purchase). France rebuilt a new empire mostly after 1850, concentrating chiefly in Africa as well as Indochina and the South Pacific. Republicans, at first hostile to empire, only became supportive when Germany after 1880 started to build its own colonial empire. As it developed, the new French empire took on roles of trade with the motherland, supplying raw materials and purchasing manufactured items. Rebuilding an empire rebuilt French prestige, especially regarding international power and spreading the French language and the Catholic religion. It also provided manpower in the World Wars.[12]

A major goal was the Mission civilisatrice or "The Civilizing Mission". 'Civilizing' the populations of Africa through spreading language and religion, were used as justifications for many of the brutal practices that came with the French colonial project.[13][14] In 1884, the leading proponent of colonialism, Jules Ferry, declared; "The higher races have a right over the lower races, they have a duty to civilize the inferior races." Full citizenship rights – assimilation – were offered, although in reality "assimilation was always receding [and] the colonial populations treated like subjects not citizens."[15] France sent small numbers of settlers to its empire, with the notable exception of Algeria, where the French settlers took power while being a minority.

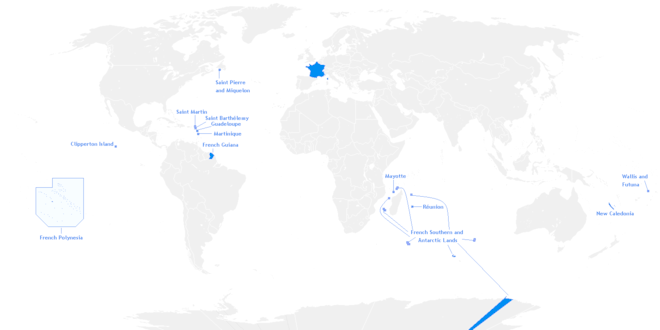

In World War II, Charles de Gaulle and the Free French took control of the overseas colonies one-by-one and used them as bases from which they prepared to liberate France. Historian Tony Chafer argues: "In an effort to restore its world-power status after the humiliation of defeat and occupation, France was eager to maintain its overseas empire at the end of the Second World War."[16] However, after 1945 anti-colonial movements began to challenge European authority. Major revolts in Indochina and Algeria proved very expensive and France lost both colonies. Then followed a relatively peaceful decolonization elsewhere after 1960. The French constitution of 27 October 1946 (Fourth Republic), established the French Union which endured until 1958. Newer remnants of the colonial empire were integrated into France as overseas departments and territories within the French Republic. These now total altogether 119,394 km² (46,098 sq. miles), with 2.7 million people in 2013. By the 1970s, says Robert Aldrich, the last "vestiges of empire held little interest for the French." He argues, "Except for the traumatic decolonization of Algeria, however, what is remarkable is how few long-lasting effects on France the giving up of empire entailed."[17]

History

First French colonial empire

The Americas

.svg.png)

During the 16th century, the French colonization of the Americas began. Excursions of Giovanni da Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier in the early 16th century, as well as the frequent voyages of French boats and fishermen to the Grand Banks off Newfoundland throughout that century, were the precursors to the story of France's colonial expansion.[18] But Spain's defense of its American monopoly, and the further distractions caused in France itself in the later 16th century by the French Wars of Religion, prevented any constant efforts by France to settle colonies. Early French attempts to found colonies in Brazil, in 1555 at Rio de Janeiro ("France Antarctique") and in Florida (including Fort Caroline in 1562), and in 1612 at São Luís ("France Équinoxiale"), were not successful, due to a lack of official interest and to Portuguese and Spanish vigilance.[19]

The story of France's colonial empire truly began on 27 July 1605, with the foundation of Port Royal in the colony of Acadia in North America, in what is now Nova Scotia, Canada. A few years later, in 1608, Samuel De Champlain founded Quebec, which was to become the capital of the enormous, but sparsely settled, fur-trading colony of New France (also called Canada).[20]

New France had a rather small population, which resulted from more emphasis being placed on the fur trade rather than agricultural settlements. Due to this emphasis, the French relied heavily on creating friendly contacts with the local First Nations community. Without the appetite of New England for land, and by relying solely on Aboriginals to supply them with fur at the trading posts, the French composed a complex series of military, commercial, and diplomatic connections. These became the most enduring alliances between the French and the First Nation community. The French were, however, under pressure from religious orders to convert them to Catholicism.[21]

Through alliances with various Native American tribes, the French were able to exert a loose control over much of the North American continent. Areas of French settlement were generally limited to the St. Lawrence River Valley. Prior to the establishment of the 1663 Sovereign Council, the territories of New France were developed as mercantile colonies. It is only after the arrival of intendant Jean Talon in 1665 that France gave its American colonies the proper means to develop population colonies comparable to that of the British. Acadia itself was lost to the British in the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Back in France there was relatively little interest in colonialism, which concentrated rather on dominance within Europe, and for most of its history, New France was far behind the British North American colonies in both population and economic development.[22][23]

In 1699, French territorial claims in North America expanded still further, with the foundation of Louisiana in the basin of the Mississippi River. The extensive trading network throughout the region connected to Canada through the Great Lakes, was maintained through a vast system of fortifications, many of them centred in the Illinois Country and in present-day Arkansas.[24]

As the French empire in North America grew, the French also began to build a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies. Settlement along the South American coast in what is today French Guiana began in 1624, and a colony was founded on Saint Kitts in 1625 (the island had to be shared with the English until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, when it was ceded outright). The Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique founded colonies in Guadeloupe and Martinique in 1635, and a colony was later founded on Saint Lucia by (1650). The food-producing plantations of these colonies were built and sustained through slavery, with the supply of slaves dependent on the African slave trade. Local resistance by the indigenous peoples resulted in the Carib Expulsion of 1660.[25] France's most important Caribbean colonial possession was established in 1664, when the colony of Saint-Domingue (today's Haiti) was founded on the western half of the Spanish island of Hispaniola. In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue grew to be the richest sugar colony in the Caribbean. The eastern half of Hispaniola (today's Dominican Republic) also came under French rule for a short period, after being given to France by Spain in 1795.[26]

Africa and Asia

French colonial expansion was not limited to the New World.

With the end of the French Wars of Religion, King Henry IV encourage various enterprises, set up to develop trade with faraway lands. In December 1600, a company was formed through the association of Saint-Malo, Laval, and Vitré to trade with the Moluccas and Japan.[27] Two ships, the Croissant and the Corbin, were sent around the Cape of Good Hope in May 1601. One was wrecked in the Maldives, leading to the adventure of François Pyrard de Laval, who managed to return to France in 1611.[27][28] The second ship, carrying François Martin de Vitré, reached Ceylon and traded with Aceh in Sumatra, but was captured by the Dutch on the return leg at Cape Finisterre.[27][28] François Martin de Vitré was the first Frenchman to write an account of travels to the Far East in 1604, at the request of Henry IV, and from that time numerous accounts on Asia would be published.[29]

From 1604 to 1609, following the return of François Martin de Vitré, Henry developed a strong enthusiasm for travel to Asia and attempted to set up a French East India Company on the model of England and the Netherlands.[28][29][30] On 1 June 1604, he issued letters patent to Dieppe merchants to form the Dieppe Company, giving them exclusive rights to Asian trade for 15 years. No ships were sent, however, until 1616.[27] In 1609, another adventurer, Pierre-Olivier Malherbe, returned from a circumnavigation of the globe and informed Henry of his adventures.[29] He had visited China and India and had an encounter with Akbar.[29]

In Senegal in West Africa, the French began to establish trading posts along the coast in 1624.

In 1664, the French East India Company was established to compete for trade in the east.

With the decay of the Ottoman Empire, in 1830 the French seized Algiers, thus beginning the colonization of French North Africa.

During the First World War, after France had suffered heavy casualties on the Western Front, they began to recruit soldiers from their African empire. By 1917, France had recruited 270,000 African soldiers.[31] Their most decorated regiments came from Morocco, but due to the ongoing Zaian War they were only able to recruit 23,000 Moroccans. African soldiers had success in the Battle of Verdun and failure in the Nivelle Offensive, but in general regardless of their usefulness, French generals did not think highly of their African troops.[31]

After the First World War, France's African war aims were not being decided by her cabinet or the official mind of the colonial ministry, but rather the leaders of the colonial movement in French Africa. The first occasion of this was in 1915–1916, when Francois Georges-Picot (both a diplomat and part of a colonial dynasty) met with the British to discuss the division of Cameroon.[31] Picot proceeded with negotiations with neither the oversight of the French president nor the cabinet. What resulted was Britain giving 9/10 of Cameroon to the French. Picot emphasized the demands of the French colonists over the French cabinet. This policy of French colonial leaders determining France's African war aims can be seen throughout much of France's empire.[32]

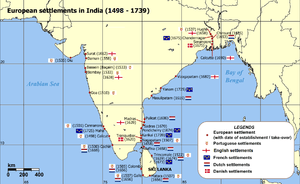

Colonies were established in India's Chandernagore (1673) and Pondichéry in the south east (1674), and later at Yanam (1723), Mahe (1725), and Karikal (1739) (see French India). Colonies were also founded in the Indian Ocean, on the Île de Bourbon (Réunion, 1664), Isle de France (Mauritius, 1718), and the Seychelles (1756).

Colonial conflict with Britain

In the middle of the 18th century, a series of colonial conflicts began between France and Britain, which ultimately resulted in the destruction of most of the first French colonial empire and the near-complete expulsion of France from the Americas. These wars were the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the American Revolution (1765–1783), the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). It may even be seen further back in time to the first of the French and Indian Wars. This cyclic conflict is sometimes known as the Second Hundred Years' War.

Although the War of the Austrian Succession was indecisive – despite French successes in India under the French Governor-General Joseph François Dupleix and Europe under Marshal Saxe – the Seven Years' War, after early French successes in Menorca and North America, saw a French defeat, with the numerically superior British (over one million to about 50 thousand French settlers) conquering not only New France (excluding the small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon), but also most of France's West Indian (Caribbean) colonies, and all of the French Indian outposts.

While the peace treaty saw France's Indian outposts, and the Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe restored to France, the competition for influence in India had been won by the British, and North America was entirely lost – most of New France was taken by Britain (also referred to as British North America), except Louisiana, which France ceded to Spain as payment for Spain's late entrance into the war (and as compensation for Britain's annexation of Spanish Florida). Also ceded to the British were Grenada and Saint Lucia in the West Indies. Although the loss of Canada would cause much regret in future generations, it excited little unhappiness at the time; colonialism was widely regarded as both unimportant to France, and immoral.[33]

Some recovery of the French colonial empire was made during the French intervention in the American Revolution, with Saint Lucia being returned to France by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, but not nearly as much as had been hoped for at the time of French intervention. True disaster came to what remained of France's colonial empire in 1791 when Saint Domingue (the Western third of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola), France's richest and most important colony, was riven by a massive slave revolt, caused partly by the divisions among the island's elite, which had resulted from the French Revolution of 1789.

The slaves, led eventually by Toussaint L'Ouverture and then, following his capture by the French in 1801, by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, held their own against French and British opponents, and ultimately achieved independence as Empire of Haiti in 1804 (Haiti became the first black republic in the world, followed by Liberia in 1847).[34] The black and mulatto population of the island (including the Spanish east) had declined from 700,000 in 1789 to 351,819 in 1804. About 80,000 Haitians died in the 1802–03 campaign alone. Of the 55,131 French soldiers dispatched to Haiti in 1802–03, 45,000, including 18 generals, had died, along with 10,000 sailors, the great majority from disease.[35] Captain [first name unknown] Sorrell of the British navy observed, "France lost there one of the finest armies she ever sent forth, composed of picked veterans, the conquerors of Italy and of German legions. She is now entirely deprived of her influence and her power in the West Indies."[36]

In the meanwhile, the newly resumed war with Britain by the French, resulted in the British capture of practically all remaining French colonies. These were restored at the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, but when war resumed in 1803, the British soon recaptured them. France's repurchase of Louisiana in 1800 came to nothing, as the success of the Haitian Revolution convinced Napoleon that holding Louisiana would not be worth the cost, leading to its sale to the United States in 1803. The French attempt to establish a colony in Egypt in 1798–1801 was not successful. Battle casualties for the campaign were at least 15,000 killed or wounded and 8,500 prisoners for France; 50,000 killed or wounded and 15,000 prisoners for Turkey, Egypt, other Ottoman lands, and Britain.[37]

Second French colonial empire (after 1830)

At the close of the Napoleonic Wars, most of France's colonies were restored to it by Britain, notably Guadeloupe and Martinique in the West Indies, French Guiana on the coast of South America, various trading posts in Senegal, the Île Bourbon (Réunion) in the Indian Ocean, and France's tiny Indian possessions; however, Britain finally annexed Saint Lucia, Tobago, the Seychelles, and the Isle de France (now Mauritius).

In 1825 Charles X sent an expedition to Haïti, resulting in the Haiti indemnity controversy.[38]

The beginnings of the second French colonial empire were laid in 1830 with the French invasion of Algeria, which was conquered over the next 17 years. One authority counts 825,000 Algerian victims of the French conquest.[39]

Franco-Tahitian War (1842–1847)

In 1838, the French naval commander Abel Aubert Dupetit Thouars responded to complaints of the mistreatment of French Catholic missionary in the Kingdom of Tahiti ruled by Queen Pōmare IV. Dupetit Thouars forced the native government to pay an indemnity and sign a treaty of friendship with France respecting the rights of French subjects in the islands including any future Catholic missionaries. Four years later, claiming the Tahitians had violated the treaty, a French protectorate was forcibly installed and the queen made to sign a request for French protection.[40][41]

Queen Pōmare left her kingdom and exiled herself to Raiatea in protest against the French and tried to enlist the help of Queen Victoria. The Franco-Tahitian War broke out between the Tahitian people and the French from 1844 to 1847 as France attempted to consolidate their rule and extend their rule into the Leeward Islands where Queen Pōmare sought refuge with her relatives. The British remained officially neutral during the war but diplomatic tensions existed between the French and British. The French succeeded in subduing the guerilla forces on Tahiti but failed to hold the other islands. In February 1847, Queen Pōmare IV returned from her self-imposed exile and acquiesced to rule under the protectorate. Although victorious, the French were not able to annex the islands due to diplomatic pressure from Great Britain, so Tahiti and its dependency Moorea continued to be ruled under the protectorate. A clause to the war settlement, known as the Jarnac Convention or the Anglo-French Convention of 1847, was signed by France and Great Britain, in which the two powers agreed to respect the independence of Queen Pōmare's allies in Leeward Islands. The French continued the guise of protection until the 1880s when they formally annexed Tahiti with the abdication of King Pōmare V on 29 June 1880. The Leeward Islands were annexed through the Leewards War which ended in 1897. These conflicts and the annexation of other Pacific islands formed French Polynesia.[41][42]

Napoleon III: 1852–1870

.jpg)

Napoleon III doubled the area of the French overseas Empire; he established French rule in New Caledonia, and Cochinchina, established a protectorate in Cambodia (1863); and colonized parts of Africa. He joined Britain in sending an army to China during Second Opium War and the Taiping Rebellion (1860), but French ventures to establish influence in Japan (1867) and Korea (1866) were less successful. His attempt to impose a European monarch, Maximilian I of Mexico on the Mexicans ended in a spectacular failure in 1867. To restore the Mexican Republic, 31,962 Mexicans died violently, including over 11,000 executed by firing squads, 8,304 were seriously wounded and 33,281 endured captivity in prisoner of war camps. Those Mexicans who fought for the monarchy sacrificed 5,671 of their number killed in combat, 2,159 badly wounded, and 4,379 taken prisoner. The French suffered 1,729 battle deaths, including 549 who died of wounds, 2,559 wounded, and 4,925 dead from disease.[43]

To carry out his new overseas projects, Napoleon III created a new Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies and appointed an energetic minister, Prosper, Marquis of Chasseloup-Laubat, to head it. A key part of the enterprise was the modernization of the French Navy; he began the construction of 15 powerful new battle cruisers powered by steam and driven by propellers; and a fleet of steam-powered troop transports. The French Navy became the second most powerful in the world, after Britain's. He also created a new force of colonial troops, including elite units of naval infantry, Zouaves, the Chasseurs d'Afrique, and Algerian sharpshooters, and he expanded the Foreign Legion, which had been founded in 1831 and won fame in the Crimea, Italy and Mexico. By the end of Napoleon III's reign, the French overseas territories had tripled in the area; in 1870 they covered a 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi), with more than 5 million inhabitants.[44]

New Caledonia becomes a French possession (1853–54)

On 24 September 1853, Admiral Febvrier Despointes took formal possession of New Caledonia and Port-de-France (Nouméa) was founded 25 June 1854. A few dozen free settlers settled on the west coast in the following years, but New Caledonia became a penal colony and, from the 1860s until the end of the transportations in 1897, about 22,000 criminals and political prisoners were sent to New Caledonia.[45]

Colonization of Senegal (1854–1865)

At the beginning of Napoleon III's reign, the presence of France in Senegal was limited to a trading post on the island of Gorée, a narrow strip on the coast, the town of Saint-Louis, and a handful of trading posts in the interior. The economy had largely been based on the slave trade, carried out by the rulers of the small kingdoms of the interior, until France abolished slavery in its colonies in 1848. In 1854, Napoleon III named an enterprising French officer, Louis Faidherbe, to govern and expand the colony, and to give it the beginning of a modern economy. Faidherbe built a series of forts along the Senegal River, formed alliances with leaders in the interior, and sent expeditions against those who resisted French rule. He built a new port at Dakar, established and protected telegraph lines and roads, followed these with a rail line between Dakar and Saint-Louis and another into the interior. He built schools, bridges, and systems to supply fresh water to the towns. He also introduced the large-scale cultivation of Bambara groundnuts and peanuts as a commercial crop. Reaching into the Niger valley, Senegal became the primary French base in West Africa and a model colony. Dakar became one of the most important cities of the French Empire and of Africa.[46]

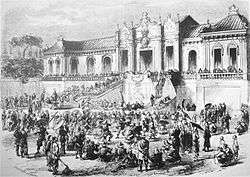

Intervention in China (1858–1860)

In 1857, after the murder of a French priest and the arrest by the Chinese police of the crew of a British merchant ship, Napoleon III joined together with Great Britain to form a military expedition to punish the Chinese government. The object of his policy was not to take territory, but to assure that the vast and lucrative Chinese market was open to French commerce, and not the exclusive trading partner of Britain. In January 1858 a combined British and French fleet bombarded and occupied Canton, and landed troops at the mouth of the Hai River in northern China. In June 1858 the Chinese government in Peking was forced to sign the Treaty of Tientsin with Britain, France, Russia and the United States. This treaty opened six additional Chinese ports to European merchant ships, allowed Christian missionary activity, and legalized the import of opium into China.

The Chinese government was reluctant to observe the treaty, so Napoleon III and the British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston decided to take more forceful action, in what became known in history as the second phase of the Second Opium War. A joint French-British expeditionary force of 8,000 men was created under a French general, Charles Cousin-Montauban, who had commanded French forces in Algeria. At the beginning of 1860 the French-British fleet sailed from Europe, and in the spring of 1860 landed the army in China. The Anglo-French army force, led by Cousin-Montauban, captured Tientsin, and then marched on the capital. On 21 September 1860 it defeated the army of the Chinese emperor at the Battle of Palikao and seized the capital Beijing. At the orders of the British commander Lord Elgin, the British and French forces burned and pillaged the Old Summer Palace of the Chinese Emperor. On 25 October 1860, the Chinese Emperor was obliged to accept a second treaty of Tientsin, opening an additional eleven new ports to European trade, making westerners immune to prosecution by Chinese courts, and establishing western diplomatic missions in Beijing. Some of the art objects taken from the looted Summer Palace were carried to France, where the Empress used them to decorate a Chinese-themed salon at the Palace of Fontainebleau, where they can be seen today.[47]

France in Korea and Japan (1866–1868)

In 1866, French diplomats in China learned that French priests had been arrested and executed in Korea, a country which had had no diplomatic or commercial contact with Europe or America. Twelve Catholic priests at the time were living in Korea, with an estimated 23,000 Korean converts, belonging to churches founded by French missionaries in the 18th century. In January 1866, King Gojong and his father, regent Daewongun, ordered the execution of most of the French priests, and ten thousand converts. A squadron of French ships, carrying eight hundred naval infantry, attempted retaliation but made little headway.[48]

In Japan the Meiji Emperor, and his enemies, the Tokugawa shogunate, both sought French military training and technology in their battle for power, known as the Boshin War. In 1867, a military mission to Japan played a key role in modernizing the troops of the shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu, and even participated on his side against Imperial troops during the Boshin war. The European representative of the Shogunate, Shibata Takenaka, approached both Britain and France, asking assistance to build a modern shipyard and to train the Shogunate army in modern western warfare. The shipyard, which became the naval base of Yokosuka, was designed by the French engineer Leonce Verny. The British, who supported the imperial faction, declined to provide trainers, but Napoleon III agreed, and in 1867 dispatched a delegation of nineteen French military experts in the fields of infantry, cavalry and artillery to Japan. They trained an elite corps, called the Denshutai, to fight on the side of the shōgun.

On the other side, the Emperor purchased from the United States a French-built ironclad warship, renamed the Kōtetsu (literally "ironclad"). It played an important role in the first modern naval battle fought in Japan. By 1868, the Imperial forces had won a decisive victory. French influence in the Japanese navy remained strong.[49]

France in Indochina and the Pacific (1858–1870)

Napoleon III also acted to increase the French presence in Indochina. An important factor in his decision was the belief that France risked becoming a second-rate power by not expanding its influence in East Asia. Deeper down was the sense that France owed the world a civilizing mission.[50]

French missionaries had been active in Vietnam since the 17th century, when the Jesuit priest Alexandre de Rhodes opened a mission there. In 1858 the Vietnamese emperor of the Nguyen Dynasty felt threatened by the French influence and tried to expel the missionaries. Napoleon III sent a naval force of fourteen gunships, carrying three thousand French and three thousand Filipino troops provided by Spain, under Charles Rigault de Genouilly, to compel the government to accept the missionaries and to stop the persecution of Catholics. In September 1858 the expeditionary force captured and occupied the port of Da Nang, and then in February 1859 moved south and captured Saigon. The Vietnamese ruler was compelled to cede three provinces to France, and to offer protection to the Catholics. The French troops departed for a time to take part in the expedition to China, but in 1862, when the agreements were not fully followed by the Vietnamese emperor, they returned. The Emperor was forced to open treaty ports in Annam and Tonkin, and all of Cochinchina became a French territory in 1864.

In 1863, the ruler of Cambodia, King Norodom, who had been placed in power by the government of Thailand, rebelled against his sponsors and sought the protection of France. The Thai Emperor granted authority over Cambodia to France, in exchange for two provinces of Laos, which were ceded by Cambodia to Thailand. In 1867, Cambodia formally became a protectorate of France.

Capture of Saigon by Charles Rigault de Genouilly on 18 February 1859, painted by Antoine Morel-Fatio

Capture of Saigon by Charles Rigault de Genouilly on 18 February 1859, painted by Antoine Morel-Fatio- Napoleon III receiving the Siamese embassy at the palace of Fontainebleau in 1864

Intervention in Syria and Lebanon (1860–1861)

In the spring of 1860, a war broke out in Lebanon, then part of the Ottoman Empire, between the quasi-Muslim Druze population and the Maronite Christians. The Ottoman authorities in Lebanon could not stop the violence, and it spread into neighboring Syria, with the massacre of many Christians. In Damascus, the Emir Abd-el-Kadr protected the Christians there against the Muslim rioters. Napoleon III felt obliged to intervene on behalf of the Christians, despite the opposition of London, which feared it would lead to a wider French presence in the Middle East. After long and difficult negotiations to obtain the approval of the British government, Napoleon III sent a French contingent of seven thousand men for a period of six months. The troops arrived in Beirut in August 1860, and took positions in the mountains between the Christian and Muslim communities. Napoleon III organized an international conference in Paris, where the country was placed under the rule of a Christian governor named by the Ottoman Sultan, which restored a fragile peace. The French troops departed in June 1861, after just under one year. The French intervention alarmed the British, but was highly popular with the powerful Catholic political faction in France, which had been alarmed by Napoleon's dispute with the Pope over his territories in Italy.[51]

Algeria

Algeria had been formally under French rule since 1830, but only in 1852 was the country entirely conquered. There were about 100,000 European settlers in the country, at that time, about half of them French. Under the Second Republic the country was ruled by a civilian government, but Louis Napoleon re-established a military government, much to the annoyance of the colonists. By 1857 the army had conquered Kabyle Province, and pacified the country. By 1860 the European population had grown to 200,000, and lands of native Algerians were being rapidly bought and farmed by the new arrivals.[52]

Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Algerians, out of a total of 3 million, were killed within the first three decades of the conquest as a result of war, massacres, disease and famine.[53][54] French losses from 1830–51 were 3,336 killed in action and 92,329 dead in the hospital.[55][56]

In the first eight years of his rule Napoleon III paid little attention to Algeria. In September 1860, however, he and the Empress Eugénie visited Algeria, and the trip made a deep impression upon them. Eugénie was invited to attend a traditional Arab wedding, and the Emperor met many of the local leaders. The Emperor gradually conceived the idea that Algeria should be governed differently from other colonies. in February 1863, he wrote a public letter to Pelissier, the Military Governor, saying: "Algeria is not a colony in the traditional sense, but an Arab kingdom; the local people have, like the colonists, a legal right to my protection. I am just as much the Emperor of the Arabs of Algeria as I am of the French." He intended to rule Algeria through a government of Arab aristocrats. Toward this end he invited the chiefs of main Algerian tribal groups to his chateau at Compiegne for hunting and festivities.[57]

Compared to previous administrations, Napoleon III was far more sympathetic to the native Algerians.[58] He halted European migration inland, restricting them to the coastal zone. He also freed the Algerian rebel leader Abd al Qadir (who had been promised freedom on surrender but was imprisoned by the previous administration) and gave him a stipend of 150,000 francs. He allowed Muslims to serve in the military and civil service on theoretically equal terms and allowed them to migrate to France. In addition, he gave the option of citizenship; however, for Muslims to take this option they had to accept all of the French civil code, including parts governing inheritance and marriage which conflicted with Muslim laws, and they had to reject the competence of religious Sharia courts. This was interpreted by some Muslims as requiring them to give up parts of their religion to obtain citizenship and was resented.

More importantly, Napoleon III changed the system of land tenure. While ostensibly well-intentioned, in effect this move destroyed the traditional system of land management and deprived many Algerians of land. While Napoleon did renounce state claims to tribal lands, he also began a process of dismantling tribal land ownership in favour of individual land ownership. This process was corrupted by French officials sympathetic to the French in Algeria who took much of the land they surveyed into public domain. In addition, many tribal leaders, chosen for loyalty to the French rather than influence in their tribe, immediately sold communal land for cash.[59]

His attempted reforms were interrupted in 1864 by an Arab insurrection, which required more than a year and an army of 85,000 soldiers to suppress. Nonetheless, he did not give up his idea of making Algeria a model where French colonists and Arabs could live and work together as equals. He traveled to Algiers for a second time on 3 May 1865, and this time he remained for a month, meeting with tribal leaders and local officials. He offered a wide amnesty to participants of the insurrection, and promised to name Arabs to high positions in his government. He also promised a large public works program of new ports, railroads, and roads. However, once again his plans met a major natural obstacle' in 1866 and 1867, Algeria was struck by an epidemic of cholera, clouds of locusts, draught and famine, and his reforms were hindered by the French colonists, who voted massively against him in the plebiscites of his late reign.[60]

French intervention in Mexico (1862–1867)

In December 1862, the conservative Mexican government was overthrown by Benito Juarez, who established a secular state and refused to pay the internal and external debts of the old government. France was the largest owner of the debt, owed 135 million gold francs of the 260 million francs total. The rest of the debt was owed to Britain (85 million francs) and Spain (40 million). Under an 1861 agreement, France, Britain and Spain organized a joint military force to compel the Mexican government to pay. A British-French flotilla of ships arrived at VeraCruz in December 1861 and landed 7500 French soldiers and 700 British soldiers, joined later by 6000 Spanish soldiers from Cuba.

Juarez opened negotiations with the international force, but it soon became evident that the French expedition had a more ambitious objective than debt repayment. Napoleon III and the Empress had been intensively lobbied by Mexican émigrés in Europe, who proposed that France establish a new conservative and Catholic government in Mexico, under a European monarch. Napoleon III was told that the new monarch would be welcomed by the entire Mexican population. He consented to launch the operation if the new monarch would be approved by a national plebiscite, as he had been. The monarch selected for this task was the Archduke Maximilian, the brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz-Joseph II, and husband of Carlota of Mexico, daughter of the King of Belgium.

When the British and Spanish realized the French goals, they withdrew from the expedition, but the French marched on Mexico City. The first attempt by General Lorencez was repulsed by the forces of General Ignacio Zaragoza at Puebla on 5 May 1862, the first defeat of a French Army since Waterloo. Napoleon III appointed a new commander, General Forey, one of the victors of Solferino, and sent 23,000 fresh soldiers. Napoleon III believed that the Mexican people would embrace the new government. He also knew that the government of the United States would be unable to prevent it, even though it was in contravention of the Monroe Doctrine, because of the American Civil War then underway, and the implicit support provided by the neighboring Confederate States of America.[61]

The reinforced French army under Forey launched a new offensive from March to June 1863. After bitter resistance, the defenders of Mexico City surrendered on 7 June 1863. Forey, disregarding Napoleon III's instructions not to install a monarch without a popular plebiscite, organized an assembly of Mexican notables who proclaimed the Mexican Empire and invited Maximilian I of Mexico to rule. Ruling President Benito Juárez and his Republican forces retreated to the countryside and fought against the French troops and the Mexican monarchists.

Maximilian was a reluctant Emperor, not arriving in Mexico until June 1864. One of his first acts was to sign an agreement that Mexico would repay France the entire cost of the war. The combined Mexican monarchist and French forces won victories up until 1865, but then the tide began to turn against them, in part because the American Civil War had ended. The U.S. government demanded that France withdraw its soldiers from Mexico. Facing a guerilla war and a financial catastrophe, the Emperor Maximilian became more and more depressed, leaving the capital for long periods and allowing the Empress Carlota to reign. Not willing to have a war with the United States, Napoleon III decided at the beginning of 1866 to withdraw French troops from Mexico. In 1863 Maximilian had sent Carlota to Europe to appeal for funds and support. She appealed to Napoleon III, but he refused to provide more troops or money. During her tour of European courts, she lost and never regained her sanity. Maximilian refused pleas that he depart, and fought against the growing partisan army of Juarez. He was captured, judged, and shot on 19 June 1867.

The misadventure in Mexico cost the lives of six thousand French soldiers and 336 million francs, in a campaign originally designed to collect 60 million francs. It also aroused the hostility of both the United States and Austria, which had lost a member of its royal family. It was also a distraction to Napoleon III, on the eve of his coming confrontation with Prussia.[62]

- The Siege of Puebla by the French Army

The execution of Maximilian I on 19 June 1867, as painted by Édouard Manet. The intervention in Mexico was a disaster for French foreign policy.

The execution of Maximilian I on 19 June 1867, as painted by Édouard Manet. The intervention in Mexico was a disaster for French foreign policy.

French–British relations

Despite the signing of the 1860 Cobden–Chevalier Treaty, a historic free trade agreement between Britain and France, and the joint operations conducted by France and Britain in the Crimea, China and Mexico, diplomatic relations between Britain and France never became close during the colonial era. Lord Palmerston, the British foreign minister from 1846 to 1851 and prime minister from 1855 to 1865, sought to maintain the balance of power in Europe; this rarely involved an alignment with France. In 1859 there were even briefly fears that France might try to invade Britain.[63] Palmerston was suspicious of France's interventions in Lebanon, Southeast Asia and Mexico. Palmerston was also concerned that France might intervene in the American Civil War (1861–65) on the side of the South.[64] The British also felt threatened by the construction of the Suez Canal (1859–1869) by Ferdinand de Lesseps in Egypt. They tried to oppose its completion by diplomatic pressures and by promoting revolts among workers.[65]

The Suez Canal was successfully built by the French, but became a joint British-French project in 1875. Both nations saw it as vital to maintaining their influence and empires in Asia. In 1882, ongoing civil disturbances in Egypt prompted Britain to intervene, extending a hand to France. France's leading expansionist Jules Ferry was out of office, and Paris allowed London to take effective control of Egypt.[66]

French–U.S. relations

During 1861 to 1862, at the beginning of the American Civil War, Napoleon III considered recognizing the Confederacy in order to protect his operations in Mexico. Washington repeatedly warned that this meant war but the emperor kept this option open, hoping to get Britain as an ally. The Union blockade of southern ports stopped the supply of cotton to textile mills in France, and caused unemployment. The Confederacy had put their faith in "King Cotton" diplomacy, expecting that the cutoff of cotton supplies would cause Britain and France to declare war to reopen the trade. Through 1862, Napoleon III met unofficially with Confederate diplomats, raising their hopes that he would unilaterally recognize the Confederacy. France was reluctant to act without collaboration with the British, who after much wavering finally rejected intervention as not worth the heavy risk of losing American food exports. Napoleon realized that a war with the U.S. without allies "would spell disaster" for France.[67] In 1863 the Confederacy realized there was no longer any chance of intervention, and expelled the French and British consuls, who were advising their citizens not to enlist in the Confederate Army. In 1865, the United States stationed a large combat Army near the Mexican border as a warning sign. Napoleon III pulled the French troops out, and the "emperor" he had imposed on Mexico was captured and shot.[68][69][70]

1870–1939

Most Frenchmen ignored foreign affairs and colonial issues. In 1914 the chief pressure group was the Parti colonial, a coalition of 50 organizations with a combined total of only 5000 members.[71]

Asia

It was only after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 and the founding of the Third Republic (1871–1940) that most of France's later colonial possessions were acquired. From their base in Cochinchina, the French took over Tonkin (in modern northern Vietnam) and Annam (in modern central Vietnam) in 1884–1885. These, together with Cambodia and Cochinchina, formed French Indochina in 1887 (to which Laos was added in 1893 and Guangzhouwan[72] in 1900).

In 1849, the French Concession in Shanghai was established, and in 1860, the French Concession in Tientsin (now called Tianjin) was set up. Both concessions lasted until 1946.[73] The French also had smaller concessions in Guangzhou and Hankou (now part of Wuhan).[74]

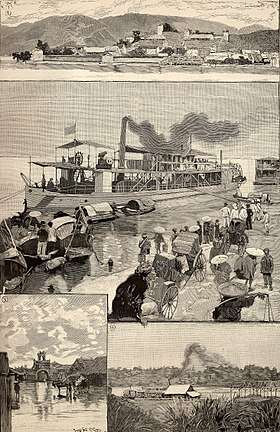

1. Panorama of Lac-Kaï, French outpost in China.

2. Yun-nan, in the quay of Hanoi.

3. Flooded street of Hanoi.

4. Landing stage of Hanoi

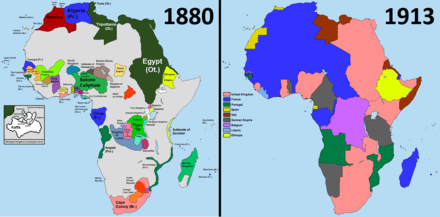

Africa

France also extended its influence in North Africa after 1870, establishing a protectorate in Tunisia in 1881 with the Bardo Treaty. Gradually, French control crystallised over much of North, West, and Central Africa by around the start of the 20th century (including the modern states of Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, Mali, Ivory Coast, Benin, Niger, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, the east African coastal enclave of Djibouti (French Somaliland), and the island of Madagascar).

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza helped to formalise French control in Gabon and on the northern banks of the Congo River from the early 1880s. The explorer Colonel Parfait-Louis Monteil traveled from Senegal to Lake Chad in 1890–1892, signing treaties of friendship and protection with the rulers of several of the countries he passed through, and gaining much knowledge of the geography and politics of the region.[75]

The Voulet–Chanoine Mission, a military expedition, set out from Senegal in 1898 to conquer the Chad Basin and to unify all French territories in West Africa. This expedition operated jointly with two other expeditions, the Foureau-Lamy and Gentil Missions, which advanced from Algeria and Middle Congo respectively. With the death (April 1900) of the Muslim warlord Rabih az-Zubayr, the greatest ruler in the region, and the creation of the Military Territory of Chad (September 1900), the Voulet-Chanoine Mission had accomplished all its goals. The ruthlessness of the mission provoked a scandal in Paris.[76]

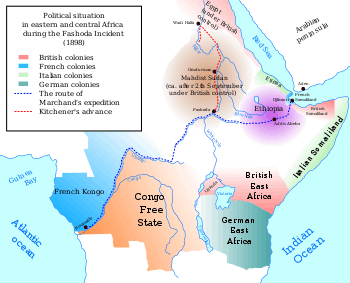

As a part of the Scramble for Africa, France aimed to establish a continuous west–east axis across the continent, in contrast with the proposed British north–south axis. Tensions between Britain and France heightened in Africa. At several points war seemed possible, but no outbreak occurred.[77] The most serious episode was the Fashoda Incident of 1898. French troops tried to claim an area in the Southern Sudan, and a British force purporting to act in the interests of the Khedive of Egypt arrived to confront them. Under heavy pressure the French withdrew, implicitly acknowledging Anglo-Egyptian control over the area. An agreement between the two states recognised the status quo: acknowledging British control over Egypt while France became the dominant power in Morocco, but France suffered a humiliating defeat overall.[78][79]

During the Agadir Crisis in 1911 Britain supported France against Germany, and Morocco became a French protectorate.

Pacific islands

At this time, the French also established colonies in the South Pacific, including New Caledonia, the various island groups which make up French Polynesia (including the Society Islands, the Marquesas, the Gambier Islands, the Austral Islands and the Tuamotus), and established joint control of the New Hebrides with Britain.

Leeward Islands (1880–1897)

In contravention of the Jarnac Convention of 1847, the French placed the Leeward Islands under a provisional protectorate by falsely convincing the ruling chiefs that the German Empire planned to take over their island kingdoms. After years of diplomatic negotiation, Britain and France agreed to abrogate the convention in 1887 and the French formally annexed all the Leeward Islands without official treaties of cession from the islands' sovereign governments. From 1888 to 1897, the natives of the kingdom of Raiatea and Tahaa led by a minor chief, Teraupo'o, fought off French rule and the annexation of the Leeward Islands. Anti-French factions in the kingdom of Huahine also attempted to fight off the French under Queen Teuhe while the kingdom of Bora Bora remained neutral but hostile to the French. The conflict ended in 1897 with the capture and exile of rebel leaders to New Caledonia and more than one hundred rebels to the Marquesas. These conflicts and the annexation of other Pacific islands formed French Polynesia.[41][42]

Final gains

The French made their last major colonial gains after World War I, when they gained mandates over the former territories of the Ottoman Empire that make up what is now Syria and Lebanon, as well as most of the former German colonies of Togo and Cameroon.

Civilising mission

A hallmark of the French colonial project in the late 19th century and early 20th century was the civilising mission (mission civilisatrice), the principle that it was Europe's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples.[80] As such, colonial officials undertook a policy of Franco-Europeanisation in French colonies, most notably French West Africa and Madagascar. During the 19th century, French citizenship along with the right to elect a deputy to the French Chamber of Deputies was granted to the four old colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyanne and Réunion as well as to the residents of the "Four Communes" in Senegal. In most cases, the elected deputies were white Frenchmen, although there were some blacks, such as the Senegalese Blaise Diagne, who was elected in 1914.[81]

Elsewhere, in the largest and most populous colonies, a strict separation between "sujets français" (all the natives) and "citoyens français" (all males of European extraction) with different rights and duties was maintained until 1946. As was pointed out in a 1927 treatise on French colonial law, the granting of French citizenship to natives "was not a right, but rather a privilege".[82] Two 1912 decrees dealing with French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa enumerated the conditions that a native had to meet in order to be granted French citizenship (they included speaking and writing French, earning a decent living and displaying good moral standards). From 1830 to 1946, only between 3,000 and 6,000 native Algerians were granted French citizenship. In French West Africa, outside of the Four Communes, there were 2,500 "citoyens indigènes" out of a total population of 15 million.[83]

French conservatives had been denouncing the assimilationist policies as products of a dangerous liberal fantasy. In the Protectorate of Morocco, the French administration attempted to use urban planning and colonial education to prevent cultural mixing and to uphold the traditional society upon which the French depended for collaboration, with mixed results. After World War II, the segregationist approach modeled in Morocco had been discredited by its connections to Vichyism, and assimilationism enjoyed a brief renaissance.[81]

In 1905, the French abolished slavery in most of French West Africa.[84] David P. Forsythe wrote: "From Senegal and Mauritania in the west to Niger in the east (what became French Africa), there was a parallel series of ruinous wars, resulting in tremendous numbers of people being violently enslaved. At the beginning of the twentieth century there may have been between 3 and 3.5 million slaves, representing over 30 percent of the total population, within this sparsely populated region."[85]

Critics of French colonialism gained an international audience in the 1920s, and often used documentary reportage and access to agencies such as the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization to make their protests heard. The main criticism was the high level of violence and suffering among the natives. Major critics included Albert Londres, Félicien Challaye, and Paul Monet, whose books and articles were widely read.[86]

While the first stages of a takeover often involved the destruction of historic buildings in order to use the site for French headquarters, archaeologists and art historians soon engaged in systematic effort to identify, map and preserve historic sites, especially temples such as Angkor Wat, Champa ruins and the temples of Luang Prabang.[87] Many French museums have collections of colonial materials. Since the 1980s the French government has opened new museums of colonial artifacts including the Musée du Quai Branly and the Cité Nationale de l’Histoire de l’Immigration, in Paris; and the Maison des Civilisations et de l’Unité Réunionnaise in Réunion.[88]

Revolt in North Africa Against Spain and France

The Berber independence leader Abd el-Krim (1882–1963) organized armed resistance against the Spanish and French for control of Morocco. The Spanish had faced unrest off and on from the 1890s, but in 1921 Spanish forces were massacred at the Battle of Annual El-Krim founded an independent Rif Republic that operated until 1926 but had no international recognition. Paris and Madrid agreed to collaborate to destroy it. They sent in 200,000 soldiers, forcing el-Krim to surrender in 1926; he was exiled in the Pacific until 1947. Morocco became quiet, and in 1936 became the base from which Francisco Franco launched his revolt against Madrid.[89]

World War II

During World War II, allied Free France, often with British support, and Axis-aligned Vichy France struggled for control of the colonies, sometimes with outright military combat. By 1943, all of the colonies, except for Indochina under Japanese control, had joined the Free French cause.[90]

The overseas empire helped liberate France as 300,000 North African Arabs fought in the ranks of the Free French.[91] However Charles de Gaulle had no intention of liberating the colonies. He assembled the conference of colonial governors (excluding the nationalist leaders) in Brazzaville in January 1944 to announce plans for postwar Union that would replace the Empire.[92] The Brazzaville manifesto proclaimed:

- the goals of the work of civilization undertaken by France in the colonies exclude all idea of autonomy, all possibility of development outside the French block of the Empire; the possible constitutional self-government in the colonies is to be dismissed.[93]

The manifesto angered nationalists across the Empire, and set the stage for long-term wars in Indochina and Algeria that France would lose in humiliating fashion.

Decolonization

The French colonial empire began to fall during the Second World War, when various parts were occupied by foreign powers (Japan in Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the United States and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany and Italy in Tunisia). However, control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle. The French Union, included in the Constitution of 1946, nominally replaced the former colonial empire, but officials in Paris remained in full control. The colonies were given local assemblies with only limited local power and budgets. There emerged a group of elites, known as evolués, who were natives of the overseas territories but lived in metropolitan France.[94]

Conflict

France was immediately confronted with the beginnings of the decolonisation movement. In Algeria demonstrations in May 1945 were repressed with an estimated 6,000 Algerians killed.[95] Unrest in Haiphong, Indochina, in November 1945 was met by a warship bombarding the city.[96] Paul Ramadier's (SFIO) cabinet repressed the Malagasy Uprising in Madagascar in 1947. French officials estimated the number of Malagasy killed from a low of 11,000 to a French Army estimate of 89,000.[97]

Also in Indochina, Ho Chi Minh's Viet Minh, which was backed by the Soviet Union and China, declared Vietnam's independence, which starting the First Indochina War. The war dragged on until 1954, when the Viet Minh decisively defeated the French at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ in northern Vietnam, which was the last major battle between the French and the Vietnamese in the First Indochina War.

Following the Vietnamese victory at Điện Biên Phủ and the signing of the 1954 Geneva Accords, France agreed to withdraw its forces from all its colonies in French Indochina, while stipulating that Vietnam would be temporarily divided at the 17th parallel, with control of the north given to the Soviet-backed Viet Minh as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh, and the south becoming the State of Vietnam under former Nguyen-dynasty Emperor Bảo Đại, who abdicated following the 1945 August Revolution under pressure from Ho.[98][99] However, in 1955, the State of Vietnam's Prime Minister, Ngô Đình Diệm, toppled Bảo Đại in a fraud-ridden referendum and proclaimed himself president of the new Republic of Vietnam. The refusal of Ngô Đình Diệm, the US-supported president of the first Republic of Vietnam [RVN], to allow elections in 1956 – as had been stipulated by the Geneva Conference – in fear of Ho Chi Minh's victory and subsequently a total communist takeover,[100] eventually led to the Vietnam War.[101]

In France's African colonies, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's insurrection, which started in 1955 and headed by Ruben Um Nyobé, was violently repressed over a two-year period, with perhaps as many as 100 people killed. However, France formally relinquished its protectorate over Morocco and granted it independence in 1956.

French involvement in Algeria stretched back a century. The movements of Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj had marked the period between the two world wars, but both sides radicalised after the Second World War. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried out by the French army. The Algerian War started in 1954. Atrocities characterized both sides, and the number killed became highly controversial estimates that were made for propaganda purposes.[102] Algeria was a three-way conflict due to the large number of "pieds-noirs" (Europeans who had settled there in the 125 years of French rule). The political crisis in France caused the collapse of the Fourth Republic, as Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled the French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962.[103][104]

The French Union was replaced in the Constitution of 1958 by the French Community. Only Guinea refused by referendum to take part in the new colonial organisation. However, the French Community dissolved itself in the midst of the Algerian War; almost all of the other African colonies were granted independence in 1960, following local referendums. Some few colonies chose instead to remain part of France, under the status of overseas départements (territories). Critics of neocolonialism claimed that the Françafrique had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence on one hand, he was creating new ties with the help of Jacques Foccart, his counsellor for African matters. Foccart supported in particular the Nigerian Civil War during the late 1960s.[105]

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, it appeared that the Empire practically had come to an end, as the remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist movements. However, there was trouble in French Somaliland (Djibouti), which became independent in 1977. There also were complications and delays in the New Hebrides Vanuatu, which was the last to gain independence in 1980. New Caledonia remains a special case under French suzerainty.[106] The Indian Ocean island of Mayotte voted in referendum in 1974 to retain its link with France and forgo independence.[107]

Demographics

French census statistics from 1931 show an imperial population, outside of France itself, of 64.3 million people living on 11.9 million square kilometers. Of the total population, 39.1 million lived in Africa and 24.5 million lived in Asia; 700,000 lived in the Caribbean area or islands in the South Pacific. The largest colonies were Indochina with 21.5 million (in five separate colonies), Algeria with 6.6 million, Morocco, with 5.4 million, and West Africa with 14.6 million in nine colonies. The total includes 1.9 million Europeans, and 350,000 "assimilated" natives.[108]

| 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan France | 39,140,000 | 40,710,000 | 41,550,000 | 41,500,000 |

| Colonies, protectorates, and mandates | 55,556,000 | 59,474,000 | 64,293,000 | 69,131,000 |

| Total | 94,696,000 | 100,184,000 | 105,843,000 | 110,631,000 |

| Percentage of the world population | 5.02% | 5.01% | 5.11% | 5.15% |

| Sources: INSEE,[109] SGF[110] | ||||

French settlers

Unlike elsewhere in Europe, France experienced relatively low levels of emigration to the Americas, with the exception of the Huguenots in British or Dutch colonies. France generally had close to the slowest natural population growth in Europe, and emigration pressures were therefore quite small. A small but significant emigration, numbering only in the tens of thousands, of mainly Roman Catholic French populations led to the settlement of the provinces of Acadia, Canada and Louisiana, both (at the time) French possessions, as well as colonies in the West Indies, Mascarene islands and Africa. In New France, Huguenots were banned from settling in the territory, and Quebec was one of the most staunchly Catholic areas in the world until the Quiet Revolution. The current French Canadian population, which numbers in the millions, is descended almost entirely from New France's small settler population.

On 31 December 1687 a community of French Huguenots settled in South Africa. Most of these originally settled in the Cape Colony, but have since been quickly absorbed into the Afrikaner population. After Champlain's founding of Quebec City in 1608, it became the capital of New France. Encouraging settlement was difficult, and while some immigration did occur, by 1763 New France only had a population of some 65,000.[111]

In 1787, there were 30,000 white colonists on France's colony of Saint-Domingue. In 1804 Dessalines, the first ruler of an independent Haiti (St. Domingue), ordered the massacre of whites remaining on the island.[112] Out of the 40,000 inhabitants on Guadeloupe, at the end of the 17th century, there were more than 26,000 blacks and 9,000 whites.[113] Bill Marshall wrote, "The first French effort to colonize Guiana, in 1763, failed utterly when tropical diseases and climate killed all but 2,000 of the initial 12,000 settlers."[114]

French law made it easy for thousands of colons, ethnic or national French from former colonies of North and West Africa, India and Indochina to live in mainland France. It is estimated that 20,000 colons were living in Saigon in 1945. 1.6 million European pieds noirs migrated from Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco.[115] In just a few months in 1962, 900,000 French Algerians left Algeria in the largest relocation of population in Europe since World War II. In the 1970s, over 30,000 French colons left Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge regime as the Pol Pot government confiscated their farms and land properties. In November 2004, several thousand of the estimated 14,000 French nationals in Ivory Coast left the country after days of anti-white violence.[116]

Apart from French-Canadians (Québécois and Acadians), Cajuns, and Métis other populations of French ancestry outside metropolitan France include the Caldoches of New Caledonia, the so-called Zoreilles, Petits-blancs with the Franco-Mauritian of various Indian Ocean islands and the Beke people of the French West Indies.

See also

- Army of the Levant

- CFA franc

- Colonialism

- Decolonization

- Evolution of the French Empire

- Francization

- French Army units with a tradition of service overseas

- 1900–1958: Troupes de marine

- 1900–1958: Troupes coloniales

- Tirailleurs

- Spahis

- Zouaves

- French colonial flags

- French colonisation of the Americas

- French law on colonialism (for teachers, 2005)

- History of France

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- List of French possessions and colonies

- New France

- Organisation internationale de la Francophonie

- Overseas France

- Postage stamps of the French colonies

- Scramble for Africa

- Timeline of imperialism

References

- Robert Aldrich, Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion (1996) p 304

- Melvin E. Page, ed. (2003). Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 218. ISBN 9781576073353.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- 1946–2011., Hyman, Paula (1998). The Jews of modern France. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520919297. OCLC 44955842.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Hinson, Glenn; Ferris, William (2010), The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 14: Folklife, University of North Carolina Press, p. 241, ISBN 9780807898550

- Gordon, Leah (2000). The Book of Vodou. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0-7641-5249-1.

- Jerryson, Michael K. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 9780199362387.

- Heenan, Patrick; Lamontagne, Monique, eds. (2014). The South America Handbook. Routledge. p. 318. ISBN 9781135973216.

- Robert Aldrich, Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion (1996) p 304

- Melvin E. Page, ed. (2003). Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 218. ISBN 9781576073353.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 501. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 502. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- Tony Chafer (2002). The End of Empire in French West Africa: France's Successful Decolonization?. Berg. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9781859735572.

- Herbert Ingram Priestley (2018). France Overseas: A Study of Modern Imperialism. p. 192. ISBN 9781351002417.

- Mathew Burrows, "'Mission civilisatrice': French cultural policy in the Middle East, 1860–1914." Historical Journal 29.1 (1986): 109–135.

- Julian Jackson, The Other Empire, Radio 3

- Tony Chafer, The end of empire in French West Africa: France's successful decolonization? (2002)see Chafer abstract Archived 14 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Robert Aldrich, Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion (1996) p 305. His section on "Ending the Empire" closes in 1980 with the independence of New Hebrides, p. 304.

- Singer, Barnett; Langdon, John (2008). Cultured Force: Makers and Defenders of the French Colonial Empire. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780299199043.

- Steven R. Pendery, "A Survey of French Fortifications in the New World, 1530–1650." in First Forts: Essays on the Archaeology of Proto-colonial Fortifications ed by Eric Klingelhofer (Brill 2010) pp. 41–64.

- Marcel Trudel, The Beginnings of New France, 1524–1663 (McClelland & Stewart, 1973).

- James R. Miller, Skyscrapers hide the heavens: A history of Indian-white relations in Canada (University of Toronto Press, 2000).

- Edward Robert Adair, "France and the Beginnings of New France." Canadian Historical Review 25.3 (1944): 246–278.

- Helen Dewar, "Canada or Guadeloupe?: French and British Perceptions of Empire, 1760–1763." Canadian Historical Review 91.4 (2010): 637–660.

- Carl J. Ekberg, French roots in the Illinois country: The Mississippi frontier in colonial times (U of Illinois Press, 2000).

- Paul Cheney, Revolutionary Commerce: Globalization and the French Monarchy (2010)

- H.P.Davis, Black Democracy The Story of Haiti (1928) pp 16–86 online free

- Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 1, Donald F. Lach pp. 93–94

- Newton, Arthur Percival (1936). The Cambridge History of the British Empire, volume 2. p. 61. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- Lach, Donald F; Van Kley, Edwin J (15 December 1998). Asia in the Making of Europe. p. 393. ISBN 9780226467658. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- A history of modern India, 1480–1950, Claude Markovits p. 144: The account of the experiences of François Martin de Vitré "incited the king to create a company in the image of that of the United Provinces"

- Andrew, C. M.

- Andrew, C. M., and A. S. . KANYA-FORSTNER. "FRANCE, AFRICA, AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR." The Journal of African History 19.1 (1978): 11–23. Print.

- Colin Gordon Calloway, The scratch of a pen: 1763 and the transformation of North America (2006). pp 165–69

- Mimi Sheller, "The 'Haytian Fear': Racial Projects and Competing Reactions to the First Black Republic." Research in Politics and Society 6 (1999): 285–304.

- Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. McFarland. 9 May 2017. p. 142.

- Scheina. Latin America's Wars.

- Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. McFarland. 9 May 2017. p. 106.

- David Patrick Geggus (2002). Haitian Revolutionary Studies. Indiana University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780253109262.

- Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. McFarland. 9 May 2017. p. 199.

- Garrett, John (1982). To Live Among the Stars: Christian Origins in Oceania. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific. pp. 253–256. ISBN 978-2-8254-0692-2. OCLC 17485209.

- Gonschor, Lorenz Rudolf (August 2008). Law as a Tool of Oppression and Liberation: Institutional Histories and Perspectives on Political Independence in Hawaiʻi, Tahiti Nui/French Polynesia and Rapa Nui (PDF) (MA thesis). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. pp. 32–51. hdl:10125/20375. OCLC 798846333.

- Matsuda2005, Matt K. (2005). "Society Islands: Tahitian Archives". Empire of Love: Histories of France and the Pacific. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 91–112. ISBN 978-0-19-534747-0. OCLC 191036857.

- Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. McFarland. 9 May 2017. p. 305.

- Pierre Milza, Napoléon III (in French, Paris: 2006), pp. 626–636

- Robert Aldrich; John Connell (2006). France's Overseas Frontier: Départements et territoires d'outre-mer. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-521-03036-6.

- G. Wesley Johnson, Double Impact: France and Africa in the age of imperialism (Greenwood 1985).

- H. M. Cole, "Origins of the French Protectorate Over Catholic Missions in China." American Journal of International Law (1940): 473–491.

- Daniel C. Kane, "Bellonet and Roze: Overzealous Servants of Empire and the 1866 French Attack on Korea," Korean Studies (1999) Vol. 23, pp 1–23.

- Ryōtarō Shiba, The last shogun: the life of Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1998) pp. 169–172

- Arthur J. Dommen, The Indochinese experience of the French and the Americans (2001) p. 4

- Girard, 1986, p. 313

- Girard, 1986, p. 320

- Jalata, Asafa (2016). Phases of Terrorism in the Age of Globalization: From Christopher Columbus to Osama bin Laden. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 92–3. ISBN 978-1-137-55234-1.

Within the first three decades, the French military massacred between half a million to one million from approximately three million Algerian people.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. pp. 364–ff. ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3.

In Algeria, colonization and genocidal massacres proceeded in tandem. From 1830 to 1847, its European settler population quadrupled to 104,000. Of the native Algerian population of approximately 3 million in 1830, about 500,000 to 1 million perished in the first three decades of French conquest.

- Bennoune, Mahfoud (22 August 2002). The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830–1987. ISBN 9780521524322.

- "French Conquest of Algeria (1829–47)".

- Girard, 1986, p. 321-322

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M. (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Jamil M. Abun-Nasr (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge U.P. p. 264. ISBN 9780521337670.

- Girard, 1986, p. 322-23

- Charles M. Hubbard (2000). The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. 163. ISBN 9781572330924.

- Jasper Ridley, Maximilian and Juárez (1992).

- Desmond Gregory (1999). No Ordinary General: Lt. General Sir Henry Bunbury (1778–1860) : the Best Soldier Historian. Fairleigh Dickinson U.P. p. 103. ISBN 9780838637913.

- David Brown, "Palmerston and Anglo–French Relations, 1846–1865", Diplomacy & Statecraft (2006) 17#4 pp. 675–692

- K. Bell, "British Policy towards the Construction of the Suez Canal, 1859–65," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (1965) Vol. 15, pp 121–143.

- A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918 (1954) pp 286–92

- Howard Jones (1999). Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War. U of Nebraska Press. p. 183. ISBN 0803225822.

- Lynn M. Case and Warren F. Spencer, The United States and France: Civil War Diplomacy (1970) pp 424–6

- Frank L. Owsley Sr., King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of the Confederate States of America (3rd ed. 2008) ch 10

- Kristine Ibsen, Maximilian, Mexico, and the Invention of Empire (2010)

- Anthony Adamthwaite, Grandeur And Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe, 1914–1940 (1995) p 6

- Foreign Concessions and Colonies

- Paul French (2011). The Old Shanghai A-Z. Hong Kong University Press. p. 215. ISBN 9789888028894.

- Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion, Google Print, p. 83, Robert Aldrich, Palgrave Macmillan, 1996, ISBN 0-312-16000-3

- Claire Hirshfield (1979). The diplomacy of partition: Britain, France, and the creation of Nigeria, 1890–1898. Springer. p. 37ff. ISBN 978-90-247-2099-6.

- Bertrand Taithe, The Killer Trail: A Colonial Scandal in the Heart of Africa (2009)

- T. G. Otte, "From 'War-in-Sight' to Nearly War: Anglo–French Relations in the Age of High Imperialism, 1875–1898," Diplomacy & Statecraft (2006) 17#4 pp 693–714.

- D. W. Brogan, France under the Republic: The Development of Modern France (1870–1930) (1940) pp 321–26

- William L. Langer, The diplomacy of imperialism: 1890–1902 (1951) pp 537–80

- Betts, Raymond F. (2005). Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890–1914. University of Nebraska Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780803262478.

- Segalla, Spencer. 2009, The Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance, 1912–1956. Nebraska University Press

- Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, De l'Indigénat. Anatomie d'un monstre juridique: Le Droit colonial en Algérie et dans l'Empire français, Éditions La Découverte, Paris, 2010, p. 59.

- Le Cour Grandmaison, p. 60, note 9.

- "Slave Emancipation and the Expansion of Islam, 1905–1914 Archived 2 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine". p.11.

- David P. Forsythe (2009). "Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 1". Oxford University Press. p. 464. ISBN 0195334027

- J.P. Daughton, "Behind the Imperial Curtain: International Humanitarian Efforts and the Critique of French Colonialism in the Interwar Years," French Historical Studies, (2011) 34#3 pp 503–528

- Robert Aldrich, "France and the Patrimoine of the Empire: Heritage Policy under Colonial Rule," French History and Civilisation (2011), Vol. 4, pp 200–209

- Caroline Ford, "Museums after Empire in Metropolitan and Overseas France," Journal of Modern History, (Sept 2010), 82#3 pp 625–661,

- Alexander Mikaberidze (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 15. ISBN 9781598843361.

- Martin Thomas, The French Empire at War, 1940–1945 (Manchester University Press, 2007)

- Robert Gildea, France since 1945 (1996) p 17

- Joseph R. De Benoist, "The Brazzaville Conference, or Involuntary Decolonization." Africana Journal 15 (1990) pp: 39–58.

- Gildea, France since 1945 (1996) p 16

- Simpson, Alfred William Brian (2004). Human Rights and the End of Empire: Britain and the Genesis of the European Convention. Oxford University Press. pp. 285–86. ISBN 978-0199267897.

- Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. New York: The Viking Press. p. 27.

- J.F.V. Keiger, France and the World since 1870 (Arnold, 2001) p 207.

- Anthony Clayton, The Wars of French Decolonization (1994) p 85

- Nash, Gary B., Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, Allan M. Winkler, Charlene Mires, and Carla Gardina Pestana. The American People, Concise Edition Creating a Nation and a Society, Combined Volume (6th Edition). New York: Longman, 2007.

- "Playboy, bon vivant and the last emperor of Vietnam: Bao Dai". South China Morning Post. 30 July 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Chapman, p. 699.

- Fear, Sean. "The Ambiguous Legacy of Ngô Đình Diệm in South Vietnam's Second Republic (1967–1975)" (PDF). University of California.

- Martin S. Alexander; et al. (2002). Algerian War and the French Army, 1954–62: Experiences, Images, Testimonies. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 6. ISBN 9780230500952.

- Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (2018). The Roots and Consequences of Independence Wars: Conflicts that Changed World History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 355–57. ISBN 9781440855993.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- James McDougall, "The Impossible Republic: The Reconquest of Algeria and the Decolonization of France, 1945–1962," Journal of Modern History 89#4 (2017) pp 772–811 excerpt

- Dorothy Shipley White, Black Africa and de Gaulle: From the French Empire to Independence (1979).

- Robert Aldrich, Greater France: A history of French overseas expansion (1996) pp 303–6

- "Mayotte votes to become France's 101st département". The Daily Telegraph. 29 March 2009.

- Herbert Ingram Priestley, France overseas: a study of modern imperialism (1938) pp 440–41.

- INSEE. "TABLEAU 1 – ÉVOLUTION GÉNÉRALE DE LA SITUATION DÉMOGRAPHIQUE" (in French). Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- Statistique générale de la France. "Code Officiel Géographique – La IIIe République (1919–1940)" (in French). Retrieved 3 November 2010.