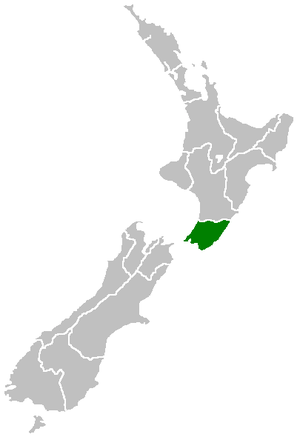

Wellington Region

The Wellington Region[3] (also known as Greater Wellington) is a local-government region of New Zealand that occupies the southern end of the North Island. The region covers an area of 8,049 square kilometres (3,108 sq mi), and has a population of 527,800 (June 2019).[1]

Wellington Region (Greater Wellington) | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Island | North Island |

| Established | 1989 |

| Seat | Wellington |

| Territorial authorities | List

|

| Government | |

| • Chairperson | Daran Ponter (Labour) |

| Area | |

| • Region | 8,049 km2 (3,108 sq mi) |

| Population (June 2019)[1] | |

| • Region | 527,800 |

| • Density | 66/km2 (170/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDT) |

| HDI (2017) | 0.944[2] very high · 1st |

| Website | www.gw.govt.nz |

The region takes its name from Wellington, New Zealand's capital city and the region's seat. The Wellington urban area, including the cities of Wellington, Porirua, Lower Hutt and Upper Hutt, accounts for 41 percent of the region's population; other major urban areas include the Kapiti conurbation (Waikanae, Paraparaumu, Raumati Beach, Raumati South, and Paekakariki) and the town of Masterton.

Local government

.jpg)

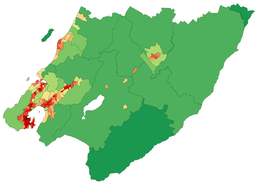

The region is administered by the Wellington Regional Council, which uses the promotional name Greater Wellington Regional Council.[4] The council region covers the conurbation around the capital city, Wellington, and the cities of Lower Hutt, Porirua, and Upper Hutt, each of which has a rural hinterland; it extends up the west coast of the North Island, taking in the coastal settlements of the Kapiti Coast District; east of the Rimutaka Range it includes three largely rural districts containing most of Wairarapa, covering the towns of Masterton, Carterton, Greytown, Featherston and Martinborough.[5] The Wellington Regional Council was first formed in 1980 from a merger of the Wellington Regional Planning Authority and the Wellington Regional Water Board.[6]

A proposal made in 2013 that nine territorial authorities amalgamate to form a single supercity met substantial local opposition and was abandoned in June 2015.[7]

The governing body of the regional council is made up of 13 councillors, representing six constituencies:[8]

- Pōneke/Wellington – 5 councillors

- Kāpiti Coast – 1

- Porirua-Tawa – 2

- Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai/Lower Hutt – 3

- Te Awa Kairangi ki Uta/Upper Hutt – 1

- Wairarapa – 1

| Position | Name | Constituency | Ticket |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chairperson | Daran Ponter | Pōneke/Wellington | Labour |

| Deputy Chairperson | Adrienne Staples | Wairarapa | Independent |

| Councillor | Glenda Hughes | Pōneke/Wellington | The Wellington Party |

| Councillor | Roger Blakeley | Pōneke/Wellington | Independent |

| Councillor | David Lee | Pōneke/Wellington | Get Wellington Moving |

| Councillor | Thomas Nash | Pōneke/Wellington | Green |

| Councillor | Ken Laban | Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai/Lower Hutt | Independent |

| Councillor | Prue Lamason | Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai/Lower Hutt | Independent |

| Councillor | Josh van Lier | Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai/Lower Hutt | Green |

| Councillor | Ros Connelly | Te Awa Kairangi ki Uta/Upper Hutt | Independent |

| Councillor | Jenny Brash | Porirua-Tawa | Independent |

| Councillor | Chris Kirk-Burnnand | Porirua-Tawa | Independent |

| Councillor | Penny Gaylor | Kāpiti Coast | Independent |

Term Wellington region

In common usage the terms Wellington region and Greater Wellington are not clearly defined, and areas on the periphery of the region are often excluded. In its more restrictive sense the region refers to the cluster of built-up areas west of the Tararua ranges. The much more sparsely populated area to the east has its own name, Wairarapa, and a centre in Masterton. To a lesser extent, the Kapiti Coast is sometimes excluded from the region. Otaki in particular has strong connections to the Horowhenua district to the north. This includes being part of the MidCentral District Health Board (DHB) area, instead of the Capital and Coast DHB area like the rest of the Kāpiti Coast.

Celia Wade-Brown, who was mayor of Wellington City from 2010 to 2016, was not in favour of the region adopting a 'super city' type council like the one in Auckland, though was in favour of reducing the number of councils from nine to "three or four".[9]

History

The Māori who originally settled the region knew it as Te Upoko o te Ika a Māui, meaning "the head of Māui's fish". Legend recounts that Kupe discovered and explored the region in about the tenth century.

The region was settled by Europeans in 1839 by the New Zealand Company. Wellington became the capital of Wellington Province upon the creation of the province in 1853, until the Abolition of the Provinces Act came into force on 1 Nov 1876.[10] Wellington became capital of New Zealand in 1865, the third capital after Russell and Auckland.

Geography

The region occupies the southern tip of the North Island, bounded to the west, south and east by the sea. To the west lies the Tasman Sea and to the east the Pacific Ocean, the two seas joined by the narrow and turbulent Cook Strait, which is 28 kilometres (17 mi) wide at its narrowest point, between Cape Terawhiti and Perano Head in the Marlborough Sounds.

The region covers 7,860 square kilometres (3,030 sq mi), and extends north to Ōtaki and almost to Eketahuna in the east.

Physically and topologically the region has four areas running roughly parallel along a northeast–southwest axis:

- The Kapiti Coast, a narrow strip of coastal plain running north from Paekakariki towards Foxton. It contains numerous small towns, many of which gain at least a proportion of their wealth from tourism, largely due to their fine beaches.

- Rough hill country inland from the Kapiti Coast, formed along the same major geologic fault responsible for the Southern Alps in the South Island. Though nowhere near as mountainous as the alps, the Rimutaka and Tararua ranges are still hard country and support only small populations, although it is in small coastal valleys and plains at the southern end of these ranges that the cities of Wellington and the Hutt Valley are located.

- The undulating hill country of the Wairarapa around the Ruamahanga River, which becomes lower and flatter in the south and terminates in the wetlands around Lake Wairarapa and contains much rich farmland.

- Rough hill country, lower than the Tararua Range but far less economic than the land around the Ruamahanga River. This and the other hilly striation are still largely forested.

There are five parks owned by the regional council:[11]

- Battle Hill Farm Forest Park

- Belmont Regional Park

- East Harbour Regional Park

- Kaitoke Regional Park

- Queen Elizabeth Park

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1991 | 400,284 | — |

| 1996 | 414,048 | +0.68% |

| 2001 | 423,765 | +0.47% |

| 2006 | 448,959 | +1.16% |

| 2013 | 471,315 | +0.70% |

| 2018 | 506,814 | +1.46% |

| Source: [12][13] | ||

Wellington Region had a population of 506,814 at the 2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 35,499 people (7.5%) since the 2013 census, and an increase of 57,855 people (12.9%) since the 2006 census. There were 185,382 households. There were 247,401 males and 259,413 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.95 males per female. Of the total population, 93,903 people (18.5%) were aged up to 15 years, 109,317 (21.6%) were 15 to 29, 231,162 (45.6%) were 30 to 64, and 72,426 (14.3%) were 65 or older. Figures may not add up to the total due to rounding.

Of those at least 15 years old, 128,928 (31.2%) people had a bachelor or higher degree, and 55,359 (13.4%) people had no formal qualifications.[12]

Over three-quarters of the 527,800 people (June 2019)[1] reside in the four cities at the southwestern corner. Other main centres of population are on the Kapiti Coast and in the fertile farming areas close to the upper Ruamahanga River in the Wairarapa.

Along the Kapiti Coast, numerous small towns sit close together, many of them occupying spaces close to popular beaches. From the north, these include Ōtaki, Waikanae, Paraparaumu, the twin settlements of Raumati Beach and Raumati South, Paekakariki and Pukerua Bay, the latter being a northern suburb of Porirua. Further north Foxton and Foxton Beach are popular holiday destinations. Each of these settlements has a population of between 2,000 and 10,000, making this moderately heavily populated.

In the Wairarapa the largest community by a considerable margin is Masterton, with a population of almost 20,000. Other towns include Featherston, Martinborough, Carterton and Greytown.

| Urban area | Population (June 2019)[1] |

% of region |

|---|---|---|

| Wellington | 215,400 | 40.8% |

| Lower Hutt | 104,900 | 19.9% |

| Porirua | 55,500 | 10.5% |

| Upper Hutt | 41,000 | 7.8% |

| Paraparaumu | 28,900 | 5.5% |

| Masterton | 20,100 | 3.8% |

| Waikanae | 12,100 | 2.3% |

| Carterton | 5,390 | 1.0% |

| Ōtaki | 4,490 | 0.9% |

| Featherston | 2,480 | 0.5% |

| Greytown | 2,420 | 0.5% |

| Paekākāriki | 1,830 | 0.3% |

| Ōtaki Beach | 1,780 | 0.3% |

| Martinborough | 1,680 | 0.3% |

Income and employment

The median income as of the 2018 census was $36,100. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 217,071 (52.6%) people were employed full-time, 58,725 (14.2%) were part-time, and 18,294 (4.4%) were unemployed.[12]

Culture and identity

Ethnicities in the 2018 census were 74.6% European/Pākehā, 14.3% Māori, 8.4% Pacific peoples, 12.9% Asian, and 3.3% other ethnicities. People may identify with more than one ethnicity.

The proportion of people born overseas was 26.9%, compared with 27.1% nationally.

Although some people objected to giving their religion, 50.2% had no religion, 35.6% were Christian, and 8.1% had other religions.[12]

| Largest groups of overseas-born residents[14] | |

| Nationality | Population (2018) |

|---|---|

| 29,043 | |

| 11,334 | |

| 8,664 | |

| 8,400 | |

| 7,410 | |

| 6,642 | |

| 6,435 | |

| 4,581 | |

| 4,047 | |

| 3,843 | |

In the 2013 census, around 25.3 percent of the Wellington region's population was born overseas, second only to Auckland (39.1 percent) and on par with the New Zealand average (25.2 percent). The British Isles is the largest region of origin, accounting for 36.5 percent of the overseas-born population in the region. Significantly, the Wellington region is home to over half of New Zealand's Tokelauean-born population.[15][16]

Catholicism was the largest Christian denomination in Wellington with 14.8 percent affiliating, while Anglicanism was the second-largest with 11.9 percent affiliating. Hinduism (2.4 percent) and Buddhism (1.6 percent) were the largest non-Christian religions in the 2013 census.[16]

Museums

Key cultural institutions in the region include Te Papa in Wellington, the Dowse Art Museum in Lower Hutt, Pataka museum and gallery in Porirua.

Economy

The subnational gross domestic product (GDP) of the Wellington region was estimated at NZ$39.00 billion in the year to March 2019, 12.9% of New Zealand's national GDP. The subnational GDP per capita was estimated at $74,251 in the same period, the highest of all New Zealand regions. In the year to March 2018, primary industries contributed $389 million (1.0%) to the regional GDP, goods-producing industries contributed $5.93 billion (15.9%), service industries contributed $27.84 billion (74.5%), and taxes and duties contributed $3.20 billion (8.6%).[17]

Transport

Public transport in the Region is well developed compared to other parts of New Zealand. It consists of buses, trains, cars, ferries and a funicular (the Wellington Cable Car). It also included trams until 1964 and trolleybuses until 2018. Buses and ferries are privately owned, with the infrastructure owned by public bodies, and public transport is often subsidised. The Regional Council is responsible for planning and subsidising public transport. The services are marketed under the name Metlink. Transdev Wellington operates the metropolitan train network, running from the Wellington CBD as far as Waikanae in the north and Masterton in the east. In the year to June 2015, 36.41 million trips were made by public transport with passengers travelling a combined 460.7 million kilometres, equal to 73 trips and 927 km per capita.[18]

The Wellington region has the lowest rate of car ownership in New Zealand; 11.7 percent of households at the 2013 census did not have access to a car, compared to 7.9 percent for the whole of New Zealand. The number of households with more than one car is also the lowest: 44.4 percent compared to 54.5 percent nationally.[19]

Biodiversity

From 2005 to 2015 there has been increase in the variety and number of native forest bird species, as well as an increase in the range of areas inhabited by these species, in Greater Wellington.[20]

The internationally recognised Ramsar estuarine wetlands site at Foxton Beach is of note as having one of the most diverse ranges of wetlands birds to be seen at any one place in New Zealand. A total of 95 species have been identified at the estuary. It is a significant area of salt marsh and mudflat and a valuable feeding ground for many birds including the migratory Eastern bar-tailed Godwit, which flies all the way from Siberia to New Zealand to escape the harsh northern winter. The estuary is also a permanent home to 13 species of birds, six species of fish and four plants species, all of which are threatened. It regularly supports about one percent of the world population of wrybills.[21]

See also

References

- "Subnational Population Estimates: At 30 June 2019". Statistics New Zealand. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- "The Local Government (Wellington Region) Reorganisation Order 1989". New Zealand Gazette: 2491 ff. 9 June 1989.

- "Legal notices". Greater Wellington Regional Council. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- "Greater Wellington Regional Council's constituencies". Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- Parks Network Plan (PDF). Greater Wellington Regional Council. 2011. p. 10. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- Michael Forbes and Caleb Harris (9 June 2015). "Wellington super-city scrapped due to lack of public support". The Dominion-Post.

- "Council and Councillors". Greater Wellington Regional Council. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "No 'super city' for Wellington - mayor". 3 News NZ. 28 January 2013.

- New Zealand Provinces 1848–77

- Greater Wellington Parks: Draft Regional Parks Management Plan

- "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Wellington Region (09). 2018 Census place summary: Wellington Region

- "2001 Census: Regional summary". archive.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- "Birthplace (detailed), for the census usually resident population count, 2006, 2013, and 2018 Censuses (RC, TA, SA2, DHB)". nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- "Birthplace (detailed), for the census usually resident population count, 2001, 2006, and 2013 (RC, TA) – NZ.Stat". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity – data tables". Statistics New Zealand. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2016. Note some percentages (e.g. ethnicity, religion) may not add to 100 percent as people could give multiple responses or object to answering.

- "Regional gross domestic product: Year ended March 2019 | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- "Greater Wellington Public Transport – Patronage". Greater Wellington Regional Council. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- "2013 Census – transport and communications in New Zealand". Statistics New Zealand. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- McArthur, Nikki; Harvey, Annette; Flux, Ian (October 2015). State and trends in the diversity, abundance and distribution of birds in Wellington City (PDF). Wellington: Greater Wellington Regional Council. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- "Manawatu Estuary". doc.govt.nz. New Zealand Department of Conservation.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wellington Region. |