War of succession

A war of succession or succession war is a war prompted by a succession crisis in which two or more individuals claim the right of successor to a deceased or deposed monarch. The rivals are typically supported by factions within the royal court. Foreign powers sometimes intervene, allying themselves with a faction. This may widen the war into one between those powers.

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

|

|

|

Related

|

Analysis

Terminology

In historiography and literature, a war of succession may also be referred to as a succession dispute, dynastic struggle, internecine conflict, fratricidal war, or any combination of these terms. Not all of these are necessarily describing armed conflict, however, and the dispute may be resolved without escalating into open warfare. Wars of succession are also often referred to as a civil war, when in fact it was a conflict within the royalty, or broader aristocracy, that civilians were dragged into,[1] and may therefore be a misnomer, or at least a misleading characterisation.

Elements

A war of succession is a type of intrastate war concerning struggle for the throne: a conflict about supreme power in a monarchy. It may become an interstate war if foreign powers intervene. A succession war may arise after (or sometimes even before) a universally recognised ruler over a certain territory passes away (sometimes without leaving behind any (legal) offspring), or is declared insane or otherwise incapable to govern, and is deposed. Next, several pretenders step forward, who are either related to the previous ruler and therefore claim to have a right to their possessions based on the hereditary principle, or have concluded a treaty to that effect. They will seek allies within the nobility and/or abroad to support their claims to the throne. After all options for a diplomatic solution –such as a sharing of power, or a financial deal– or a quick elimination –e.g. by assassination or arrest– have been exhausted, a military confrontation will follow.[3] Quite often such succession disputes can lead to long-lasting wars.

Some wars of succession are about women's right to inherit. This does not exist in some countries (a "sword fief", where the Salic law applies, for example), but it does in others (a "spindle fief").[4] Often a ruler who has no sons, but does have one or more daughters, will try to change the succession laws so that a daughter can succeed him. Such amendments will then be declared invalid by opponents, invoking the local tradition.

In some cases, wars of succession could also be centred around the reign in prince-bishoprics. Although these were formally elective monarchies without hereditary succession, the election of the prince-bishop could be strongly intertwined with the dynastic interests of the noble families involved, each of whom would put forward their own candidates. In case of disagreement over the election result, waging war was a possible way of settling the conflict. In the Holy Roman Empire, such wars were known as diocesan feuds.

It can sometimes be difficult to determine whether a war was purely or primarily a war of succession, or that other interests were at play as well that shaped the conflict in an equally or more important manner, such ideologies (religions, secularism, nationalism, liberalism, conservatism), economy, territory and so on. Many wars are not called 'war of succession' because hereditary succession was not the most important element, or despite the fact that it was. Similarly, wars can also be unjustly branded a 'war of succession' whilst the succession was actually not the most important issue hanging in the balance.

Polemology

The origins of succession wars lie in feudal or absolutist systems of government, in which the decisions on war and peace could be made by a single sovereign without the population's consent. The politics of the respective rulers was mainly driven by dynastic interests. German historian Johannes Kunisch (1937–2015) ascertained: "The all-driving power was the dynasties' law of the prestige of power, the expansion of power, and the desire to maintain themselves."[1] Moreover, the legal and political coherence of the various provinces of a 'state territory' often consisted merely in nothing more than having a common ruler. Early government systems were therefore based on dynasties, the extinction of which immediately brought on a state crisis. The composition of the governmental institutions of the various provinces and territories also eased their partitioning in case of a conflict, just like the status of claims on individual parts of the country by foreign monarchs.[5]

To wage a war, a justification is needed (Jus ad bellum). These arguments may be put forward in a declaration of war, to indicate that one is justly taking up arms. As the Dutch lawyer Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) noted, these must make clear that one is unable to pursue their rightful claims in any other way.[6] The claims to legal titles from the dynastic sphere were a strong reason for war, because international relations primarily consisted of inheritance and marriage policies until the end of the Ancien Régime. These were often so intertwined that it had to lead to conflict. Treaties that led to hereditary linkages, pawning and transfers, made various relations more complicated, and could be utilised for claims as well. That claims were made at all is due to the permanent struggle for competition and prestige between the respective ruling houses. On top of that came the urge of contemporary princes to achieve "glory" for themselves.[5]

After numerous familial conflicts, the principle of primogeniture originated in Western Europe the 11th century, spreading to the rest of Europe (with the exception of Russia) in the 12th and 13th century; it has never evolved outside Europe.[7] However, it has not prevented the outbreak of wars of succession. A true deluge of succession wars occurred in Europe between the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and the Coalition Wars (1792–1815).[8] According to German historian Heinz Duchhardt (1943) the outbreak of wars of succession in the early modern period was stimulated on the one hand by the uncertainty about the degree to which regulations and agreements on hereditary succession were to be considered a respectable part of emerging international law. On the other hand, there was also a lack of effective means to provide them recognition and validation.[9]

According to British statesman Henry Brougham (Lord Chancellor 1830–34), there were more and longer wars of succession in Europe between 1066 and the French Revolution (1789–99) than all other wars put together. "A war of succession is the most lasting of wars. The hereditary principle keeps it in perpetual life – [whereas] a war of election is always short, and never revives", he opined, arguing for elective monarchy to solve the problem.[10]

In the Mughal Empire, there was no tradition of primogeniture.[11] Instead it was customary for sons to overthrow their father, and for brothers to war to the death among themselves.[12] In Andean civilizations such as the Inca Empire (1438–1533), it was customary for a lord to pass on his reign to the son he perceived to be the most able, not necessarily his oldest son; sometimes he chose a brother instead. After the Spanish colonization of the Americas began in 1492, some Andean lords began to assert their eldest-born sons were the only 'legitimate' heirs (as was common to European primogeniture customs), while others maintained Andean succession customs involving the co-regency of a younger son of a sitting ruler during the latter's lifetime, each whenever the circumstances favoured either approach.[13]

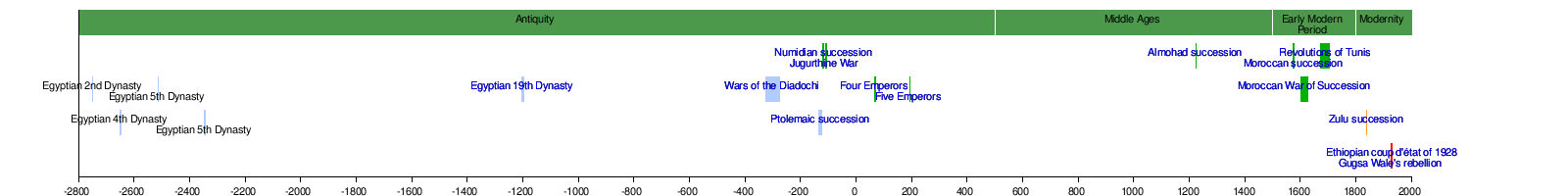

List of wars of succession

Note: Wars of succession in transcontinental states are mentioned under the continents where their capital city was located. Names of wars that have been given names by historians are capitalised; the others, whose existence has been proven but not yet given a specific name, are provisionally written in lowercase letters (except for the first word, geographical and personal names).

Africa

- Egypt

- West and North Africa

- Central and Southern Africa

- East Africa

- Ancient Egyptian wars of succession[14]

- Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of Alexander's Successors (323–277 BCE), after the death of king Alexander the Great of Macedon

- Ptolemaic war of succession (132–124 BCE), between Cleopatra II and Ptolemy VIII Physcon over the rightful succession of Ptolemy VI Philometor

- Numidian war of succession (118–112 BCE), after the death of king Micipsa of Numidia; this spilled over into the Roman–Numidian Jugurthine War (112–106 BCE)

- Almohad war of succession (1224), after the death of caliph Yusuf al-Mustansir of the Almohad Caliphate[15]

- Moroccan war of succession (1574–1578), after the death of sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib of the Saadi dynasty

- Moroccan War of Succession (1603–1627)[16]

- Revolutions of Tunis or the Muradid War of Succession (1675–1705), after the death of bey Murad II of Tunis

- Zulu war of succession (1839–1840), between the brothers Dingane and Mpande after the Battle of Blood River[17]

- Ethiopian coup d'état of 1928 and Gugsa Wale's rebellion (1930), about the (future) succession of empress Zewditu of the Ethiopian Empire by Haile Selassie

Asia

- Central Asia

- East Asia

- North Asia

- Persia & Afghanistan

- South Asia

- Southeast Asia

- West Asia

Ancient Asia

- (historicity contested) Kurukshetra War, also called the Mahabharata or Bharata War (dating heavily disputed, ranging from 5561 to around 950 BCE), between the Pandava and Kaurava branches of the ruling Lunar dynasty over the throne at Hastinapura.[18] It is disputed whether this event actually occurred as narrated in the Mahabharata.

- Rebellion of the Three Guards (c. 1042–1039 BCE), after the death of King Wu of Zhou

- (historicity contested) War of David against Ish-bosheth (c. 1007–1005 BCE), after the death of king Saul of the united Kingdom of Israel. It is disputed whether this event actually occurred as narrated in the Hebrew Bible. It allegedly began as a war of secession, namely of Judah (David) from Israel (Ish-bosheth), but eventually the conflict was about the succession of Saul in both Israel and Judah

- Neo-Assyrian war of succession (826–820 BCE), in anticipation of the death of king Shalmaneser III of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (died 824 BCE) between his sons Assur-danin-pal and Shamshi-Adad[19]

- Jin wars of succession (8th century–376 BCE), a series of wars over control of the Chinese feudal state of Jin (part of the increasingly powerless Zhou Dynasty)

- Jin–Quwo wars (739–678 BCE), dynastic struggles between two branches of Jin's ruling house

- Li Ji unrest (657–651 BCE), about the future succession of Duke Xian of Jin

- War of the Zhou succession (635 BCE), where Jin assisted King Xiang of Zhou against his brother, Prince Dai, who claimed the Zhou throne

- Partition of Jin (c. 481–403 BCE), a series of wars between rival noble families of Jin, who eventually sought to divide the state's territory amongst themselves at the expense of Jin's ruling house. The state was definitively carved up between the successor states of Zhao, Wei and Han in 376 BCE.

- War of Qi's succession (643–642 BCE), after the death of Duke Huan of Qi

- Persian war of succession (404–401 BCE) ending with the Battle of Cunaxa, after the death of Darius II of the Achaemenid Empire

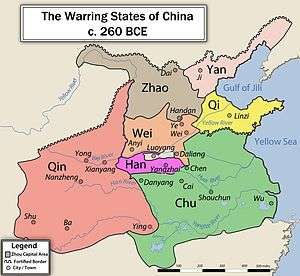

- Warring States period (c. 403–221 BCE), a series of dynastic interstate and intrastate wars during the Eastern Zhou dynasty of China over succession and territory

- War of the Wei succession (370–367 BCE), after the death of Marquess Wu of Wei

- Qin's wars of unification (230–221 BCE), to enforce Qin's claim to succeeding the Zhou dynasty (which during the Western Zhou period ruled all the Chinese states), that Qin had ended in 256 BCE

- Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of Alexander's Successors (323–277 BCE), after the death of king Alexander the Great of Macedon

- Maurya war of succession (272–268 BCE), after the death of emperor Bindusara of the Mauryan Empire; his son Ashoka the Great defeated and killed his brothers, including crown prince Susima[20]

- Chu–Han Contention (206–202 BCE), after the surrender and death of emperor Ziying of the Qin dynasty; the rival rebel leaders Liu Bang and Xiang Yu sought to set up their own new dynasties

- Lü Clan Disturbance (180 BCE), after the death of Empress Lü of the Han dynasty

- Seleucid Dynastic Wars (157–63 BCE), a series of wars of succession that were fought between competing branches of the Seleucid Royal household for control of the Seleucid Empire

- Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BCE) between the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Pontus after the death of king Nicomedes IV of Bithynia

- Hasmonean Civil War (67–63 BCE), between Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II after the death of their mother, queen Salome Alexandra

- Parthian war of succession (57–54 BCE), between Mithridates IV and his brother Orodes II after killing their father, king Phraates III

- The Roman invasion of Parthia in 54 BCE, ending catastrophically at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, was partially motivated by or justified as supporting Mithridates' claim to the Parthian throne[21]

- Red Eyebrows and Lulin Rebellions (17–23 CE), revolts against Xin dynasty emperor Wang Mang to restore the Han dynasty; both rebel armies had their own candidates, however

- Han civil war (23–36), Liu Xiu's campaigns against pretenders and regional warlords who opposed the rule of the Gengshi Emperor (23–25) and his own rule (since 25)[22]

- Second Red Eyebrows Rebellion (23–27), after the death of Wang Mang, against the Gengshi Emperor, the Lulin rebel candidate to succeed Wang Mang

- War of the Armenian Succession (54–66), caused by the death of Roman emperor Claudius, after which the rival pretender Tiridates was installed by king Vologases I of Parthia, unacceptable to new emperor Nero[23]

- Parthian wars of succession between Vologases III, Osroes I, Parthamaspates, Mithridates V and Vologases IV (105–147), after the death of king Pacorus II of Parthia

- Trajan's Parthian campaign (115–117), the intervention of the Roman emperor Trajan in favour of Parthamaspates[23]

- Three Kingdoms Period (184–280), after the death of emperor Ling of Han[note 1]

- Dynastic struggle between Vologases VI and Artabanus IV (213–222), after the death of their father Vologases V of Parthia

- Parthian war of Caracalla (216–217), Roman intervention in the Parthian dynastic struggle against Artabanus IV

- War of the Eight Princes (291–306), after the death of emperor Sima Yan of the Chinese Jin dynasty

- (historicity contested) A war of succession in the Gupta Empire after the death of emperor Kumaragupta I (c. 455), out of which Skandagupta emerged victorious. Historical sources do not make clear whether the events described constituted a war of succession, and whether it even took place as narrated.[24]

- Sasanian war of succession (457–459) between Hormizd III and Peroz I after the death of their father, shahanshah Yazdegerd II of the Sasanian Empire

- War of the Uncles and Nephews (465–c.495) after the death of emperor Qianfei of the Liu Song dynasty[25]

- Prince Hoshikawa Rebellion (479–480), after the death of emperor Yuryaku of Japan

Medieval Asia

- Wei civil war (530–550), after the assassination of would-be usurper Erzhu Rong by emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei, splitting the state into Western Wei (Yuwen clan) and Eastern Wei (Gao clan)

- Göktürk civil war or Turkic interregnum (581–587), after the death of Gökturk khagan Taspar Qaghan of the First Turkic Khaganate[26]

- Sasanian civil war of 589-591, about the deposition, execution and succession of shahanshah Hormizd IV of the Sasanian Empire

- Sui war of succession (604), after the death of Emperor Wen of the Sui dynasty[27]

- Chalukya war of succession (c. 609), after the death of king Mangalesha of the Chalukya dynasty[28]

- Transition from Sui to Tang (613–628): with several rebellions against his rule going on, Emperor Yang of Sui was assassinated in 618 by rebel leader Yuwen Huaji, who put Emperor Yang's nephew Yang Hao on the throne as puppet emperor, while rebel leader Li Yuan, who had previously made Emperor Yang's grandson Yang You his puppet emperor, forced the latter to abdicate and proclaimed himself emperor, as several other rebel leaders had also done.

- Sasanian civil war of 628–632 or Sasanian Interregnum, after the execution of shahanshah Khosrow II of the Sasanian Empire

- The historical Fitnas in Islam:

- First Fitna (656–661): after the death of caliph Uthman between the Umayyads and Ali's followers (Shiites)

- Second Fitna (680–692; in strict sense 683–685): a series of conflicts between Umayyads, Zubayrids and Alids (Shiites)

- Third Fitna (744–750/752): a series of civil wars within and rebellions against the Umayyad Caliphate, ending with the Abbasid Revolution

- Fourth Fitna (809–827): a succession war within the Abbasid Caliphate

- War of the Goguryeo succession (666–668), after the death of military dictator Yeon Gaesomun of Goguryeo, see Goguryeo–Tang War (645–668)

- Jinshin War (672), after the death of emperor Tenji of Japan

- Twenty Years' Anarchy (695–717), after the deposition of emperor Justinian II of the Byzantine Empire

- Rashtrakuta war of succession (c. 793), after the death of emperor Dhruva Dharavarsha of the Rashtrakuta dynasty[29]

- Anarchy at Samarra (861–870), after the murder of caliph Al-Mutawakkil of the Abassid Caliphate

- Later Three Kingdoms of Korea (892–936), began when two rebel leaders, claiming to be heirs of the former kings of Baekje and Goguryeo, revolted against the reign of queen Jinseong of Silla

- Pratihara war of succession (c. 910–913), after the death of king Mahendrapala I of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty[30]

- Anarchy of the 12 Warlords (966–968), after the death of king Ngô Quyền of Vietnam

- Afghan War of Succession (997–998),[31] after the death of emir Sabuktigin of the Ghaznavids

- Afghan war of succession (1030), after the death of sultan Mahmud of Ghazni

- Afghan War of Succession (1041), after the death of sultan Mas'ud I of Ghazni[31]

- Seljuk War of Succession (1092–1105), after the death of sultan Malik Shah I of the Seljuk Empire[32]

- Hōgen Rebellion (1156), Heiji Rebellion (1160) and Genpei War (1180–1185), after the death of emperor Konoe of Japan, between clans over control of the imperial family

- Pandyan Civil War (1169–1177): king Parakrama Pandyan I and his son Vira Pandyan III against Kulasekhara Pandya of Chola

- War of the Antiochene Succession (1201–1219), after the death of prince Bohemond III of Antioch

- War of the Lombards (1228–1243), after the death of queen Isabella II of Jerusalem and Cyprus

- Ayyubid war of succession (1238–1249), after the death of sultan Al-Kamil of the Ayyubid dynasty

- Toluid Civil War (1260–1264), after the death of great khan Möngke Khan of the Mongol Empire

- Berke–Hulagu war (1262), a proxy war of the Toluid Civil War

- Kaidu–Kublai war (1268–1301/4), continuation of the Toluid Civil War caused by Kaidu's refusal to recognise Kublai Khan as the new great khan

- Chagatai wars of succession (1307–1331), after the death of khan Duwa of the Chagatai Khanate[33]

- Pandya Fratricidal War (c. 1310–?), after the death of king Maravarman Kulasekara Pandyan I of the Pandya dynasty[34][35]

- Golden Horde war of succession (1312–1320?), after the death of khan Toqta of the Golden Horde

- War of the Two Capitals (1328–1332), after the death of emperor Yesün Temür of the Yuan dynasty

- Disintegration of the Ilkhanate (1335–1353), after the death of il-khan Abu Sa'id of the Ilkhanate

- Nanboku-chō period or Japanese War of Succession[36] (1336–1392), after the ousting and death of emperor Go-Daigo of Japan

- Trapezuntine Civil War (1340–1349), after the death of emperor Basil of Trebizond

- Forty Years' War (1368–1408) after the death of king Thado Minbya of Ava; the war raged within and between the Burmese kingdoms of Ava and Pegu as the successors of the Pagan Kingdom[37]

- Delhi war of succession (1394–1397), after the death of sultan Ala ud-din Sikandar Shah of the Tughlaq dynasty (Delhi Sultanate)[38][39]

- Strife of Princes (1398–1400), after king Taejo of Joseon appointed his eighth son as his successor instead of his disgruntled fifth, who rebelled when he learnt that his half-brother was conspiring to kill him (see also History of the Joseon dynasty § Early strife)[40]

- Jingnan Rebellion (1399–1402), after the death of the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty

- Timurid wars of succession (1405–1507):

- First Timurid war of succession (1405–1409/11), after the death of amir Timur of the Timurid Empire[41]

- Second Timurid war of succession (1447–1459), after the death of sultan Shah Rukh of the Timurid Empire[41]

- Third Timurid war of succession (1469–1507), after the death of sultan Abu Sa'id Mirza of the Timurid Empire[41]

- Sekandar–Zain al-'Abidin war (1412–1415): according to the Ming Shilu, Sekandar was the younger brother of the former king, rebelled and plotted to kill the current king Zain al-'Abidin to claim the throne; however, the Ming dynasty had recognised the latter as the legitimate ruler, and during the fourth treasure voyage of admiral Zheng He, the Chinese intervened and defeated Sekandar.[42]

- Chi Lu Buli Rebellion (1453), after the death of king Shō Kinpuku of the Ryukyu Kingdom

- Sengoku period (c. 1467–1601) in Japan

- Ōnin War (1467–1477), concerning the future succession of shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa of Japan

- Aq Qoyunlu war(s) of succession (1470s–1501), after the death of shahanshah Uzun Hasan of the Aq Qoyunlu state[43][44]

Early Modern Asia

- Khandesh war of succession (1508–1509), after the death of sultan Ghazni Khan of the Farooqi dynasty (Sultanate of Khandesh)[45]

- Northern Yuan war of succession (1517–15??), after the death of khagan Dayan Khan of the Northern Yuan dynasty[46]

- Gujarati war of succession (1526–1527), after the death of sultan Muzaffar Shah II of the Gujarat Sultanate[47]

- Mughal war of succession (1540–1552), between the brothers Humayun and Kamran Mirza about the succession of their already 10 years earlier deceased father, emperor Babur of the Mughal Empire[48]

- Safavid war of succession (1576–1578), after the death of shah Tahmasp I of Persia[49]

- Mughal war of succession (1601–1605), in advance of the death of emperor Akbar of the Mughal Empire[50]

- Karnataka war of succession (1614–1617), after the death of emperor Venkatapati Raya of the Vijayanagara Empire[51]

- Mughal war of succession (1627–1628), after the death of emperor Nuruddin Salim Jahangir of the Mughal Empire

- Mughal war of succession (1657–1661),[52] after grave illness of emperor Shah Jahan of the Mughal Empire[12]

- The Javanese Wars of Succession (1677–1755), between local pretenders and candidates of the Dutch East India Company

- First Javanese War of Succession (1677–1707)

- Second Javanese War of Succession (1719–1722)

- Third Javanese War of Succession (1749–1755)

- Sikkimese War of Succession (c. 1699–1708), after the death of chogyal Tensung Namgyal of the Kingdom of Sikkim[53]

- Mughal war of succession (1707–1709), after the death of emperor Aurangzeb of the Mughal Empire[54]

- Mughal war of succession (1712–1720), after the death of emperor Bahadur Shah I of the Mughal Empire[54]

- Marava War of Succession (1720–1729), after the death of raja Raghunatha Kilavan of the Ramnad estate

- Persian or Iranian Wars of Succession (1725–1796)[55]

- Safavid war of succession (1725–1729), after a Hotak invasion and the imprisonment of shah Sultan Husayn of Safavid Persia

- Afsharid war of succession (1747–1757), after the death of shah Nadir Shah of Afsharid Persia

- Zand war of succession (1779–1796), after the death of Karim Khan of Zand Persia

- Carnatic Wars (1744–1763), territorial and succession wars between several local, nominally independent princes in the Carnatic, in which the British East India Company and French East India Company mingled

- First Carnatic War (1744–1748), part of the War of the Austrian Succession between, amongst others, France on the one hand, and Britain on the other

- Second Carnatic War (1749–1754), about the succession of both the nizam of Hyderabad and the nawab of Arcot

- Third Carnatic War (nl) (1756–1763), after the death of nawab Alivardi Khan of Bengal; part of the global Seven Years' War between amongst others France on the one hand and Britain on the other

- Maratha war of succession (1749–1752), after the death of maharaja Shahu I of the Maratha Empire[56]

- Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775–1819): wars of succession between peshwas, in which the British intervened, and conquered the Maratha Empire

- First Anglo-Maratha War (1775–1782), after the death of peshwa Madhavrao I; pretender Raghunath Rao invoked British help, but lost

- Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), pretender Baji Rao II, son van Raghunath Rao, triumphed with British help and became peshwa, but had to surrender much power and territory to the British

- Third Anglo-Maratha War, also Pindari War (1816–1819), peshwa Baji Rao II revolted against the British in vain; the Maratha Empire was annexed

Modern Asia

- Afghan Wars of Succession (1793–1834?), after the death of emir Timur Shah Durrani of Afghanistan[58]

- First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), British–Indian invasion of Afghanistan under the pretext of restoring the deposed emir Shah Shujah Durrani[59]

- Pahang Civil War (1857–1863), after the death of raja Tun Ali of Pahang

- Later Afghan War of Succession (1865–1870), after the death of emir Dost Mohammed Khan of Afghanistan

- The Dutch East Indies Army's 1859–1860 Bone Expeditions dealt with two wars of succession in the neighbouring Sulawesi kingdoms of Bone and Wajo

- In the war of the Bone succession (1858–1860), the Dutch supported pretender Ahmad Sinkkaru' Rukka against queen Besse Arung Kajuara after the death of her husband, king Aru Pugi[60][61]

- In the War of the Wajo Succession (1858–1861), the Dutch supported pretender Pata Hassim after the death of raja Tulla[62]

Europe

- British Islands

- Scandinavia, Baltics & Eastern Europe

- Low Countries

- Central Europe (HRE)

- France & Italy

- Spain & Portugal

- Southeastern Europe

Ancient Europe

|

|

_01.jpg) |

|

| Year of the Four Emperors: a war of succession between Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian. | |||

- Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of Alexander's Successors (323–277 BCE), after the death of king Alexander the Great of Macedon

- First War of the Diadochi (322–320 BCE), after regent Perdiccas tried to marry Alexander the Great's sister Cleopatra of Macedon and thus claim the throne

- Second War of the Diadochi (318–315 BCE), after the death of regent Antipater, whose succession was disputed between Polyperchon (Antipater's appointed successor) and Cassander (Antipater's son)

- Epirote war of succession (316–297 BCE), after the deposition of king Aeacides of Epirus during his intervention in the Second War of the Diadochi until the second enthronement of his son Pyrrhus of Epirus and the death of usurper Neoptolemus II of Epirus

- Third War of the Diadochi (314–311 BCE), after the diadochs conspired against Antigonus I Monophthalmus and Polyperchon

- Fourth War of the Diadochi (308/6–301 BCE), resumption of the Third. During this war, regent Antigonus and his son Demetrius both proclaimed themselves king, followed by Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and eventually Cassander.

- Struggle over Macedon (298–285 BCE), after the death of king Cassander of Macedon

- Struggle of Lysimachus and Seleucus (285–281 BCE), after jointly defeating Demetrius and his son Antigonus Gonatas

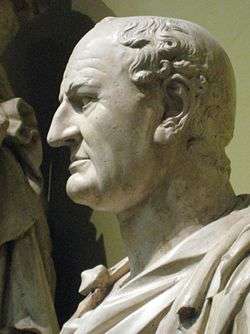

- Year of the Four Emperors (68–69 CE), a rebellion in the Roman Empire that became a war of succession after the suicide of emperor Nero

- Year of the Five Emperors (193), the beginning of a war of succession that lasted until 197, after the assassination of the Roman emperor Commodus

- Crisis of the Third Century (235–284), especially the Year of the Six Emperors (238), a series of wars between barracks emperors after the assassination of Severus Alexander

- Civil wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324), after the death of Augustus (senior Roman emperor) Constantius I Chlorus

- War of Magnentius (350–353), after the assassination of Roman co-emperor Constans I

- War between Western Roman emperor Eugenius and Eastern Roman emperor Theodosius I (392–394), after the death of emperor Valentinian II, resulting in the Battle of the Frigidus

- War of the Hunnic succession (453–454), after the death of Attila, ruler of the Huns

Early Medieval Europe

- Twenty Years' Anarchy (695–717), after the deposition of emperor Justinian II of the Byzantine Empire

- Frankish Civil War (715–718) (nl), after the death of mayor of the palace Pepin of Herstal

- Carolingian wars of succession (830–842), a series of armed conflicts in the late Frankish Carolingian Empire about the (future) succession of emperor Louis the Pious[63]

- War of the Northumbrian succession (865–867), between king Osberht and king Ælla of Northumbria; their infighting was interrupted when the Great Heathen Army invaded, against which they vainly joined forces

- Serbian war of succession (892–897), after the death of prince Mutimir of Serbia[64]

- Svatopluk II rebellion (895–899?), after the death of duke Svatopluk I of Great Moravia

- Æthelwold's Revolt (899–902), after the death of king Alfred the Great

- War of the Leonese succession (951–956), after the death of king Ramiro II of Léon

- Kievan war of succession or Russian Dynastic War (972–980) after the death of king Sviatoslav I of Kiev[65]

- War of the Leonese succession (982–984), continuation of the last Leonese war of succession

High Medieval Europe

- War of the Burgundian Succession (1002–1016), after the death of duke Henry I the Great of Burgundy

- Fitna of al-Andalus (1009–1031), after the deposition of caliph Hisham II of Córdoba

- Lower Lorrainian war of succession (1012–1018), after the death of Otto, Duke of Lower Lorraine[66]

- Kievan succession crisis (1015–1019), after the death of grand prince Vladimir the Great of the Kievan Rus'

- Bolesław I's intervention in the Kievan succession crisis (1018), king Bolesław I the Brave of Poland supported Sviatopolk the Accursed's claim against Yaroslav the Wise

- Norwegian War of Succession[67] (1025/6–1035), after the departure of king Cnut the Great of Denmark to England; it only became a war of succession when king Olaf II of Norway was deposed in 1028 and died in battle in 1030

- Norman war of succession (1026), after the death of duke Richard II of Normandy between his sons Richard III and Robert I

- Norman war of succession (1035–1047), after the death of duke Robert I of Normandy. The Battle of Val-ès-Dunes is generally regarded as having secured the reign of William of Normandy[68][note 2]

- Danish war of succession (1042–1043), after the death of king Harthacnut (Canute III) of Denmark

- Norman conquest of Maine (1062–1063), after the death of count Herbert II of Maine[69][70]

- War of the Three Sanchos (1065–1067), after the death of king Ferdinand the Great

- Harald Hardrada's invasion of England involving the Battle of Fulford and the Battle of Stamford Bridge (1066), after the death of king Edward the Confessor of England

- Norman invasion of England (1066–1075), after the death of king Edward the Confessor of England

- War of the Flemish succession (1070–1071), after the death of count Baldwin VI of Flanders

- Rebellion of 1088, after the death of William the Conqueror of Normandy and England

- Anglo-Norman war of succession (1101–1106), after the death of king William II of England

- War of the Flemish succession (1127–1128), after the assassination of count Charles I "the Good" of Flanders

- Civil war era in Norway or Norwegian Civil War(s) (1130–1240), after the death of king Sigurd the Crusader of Norway

- The Anarchy (1135–1154), after the death of king Henry I of England

- Baussenque Wars (1144–1162), after the death of count Berenguer Ramon I of Provence

- Danish Civil War (1146–1157), after the abdication of king Eric III of Denmark

- Serbian war of succession (c. 1166–1168), after the brothers Tihomir of Serbia and Stefan Nemanja failed to properly share the inheritance of their father Zavida[71]

- War of the Namurois–Luxemburgish succession (1186–1263/5), after the decades-long childless count Henry the Blind of Namur and Luxemburg, having designated Baldwin V of Hainaut his heir in 1165, after all fathered Ermesinde in 1186 and tried to change his succession in her favour. Although the struggle over Luxemburg was resolved in 1199 in favour of Ermesinde, she and Baldwin and their successors would continue to fight over Namur until it was sold to Guy of Dampierre in 1263 or 1265.[72][73]

- Sicilian war of succession (1189–1194), after the death of king William II of Sicily

- Angevin war of succession (1199–1204), after the death of Richard the Lionheart of England, Normandy, Aquitaine, Anjou, Brittany, Maine and Touraine, collectively known as the Angevin Empire[74]

- The French invasion of Normandy (1202–1204) was the last part of the Angevin war of succession

- Fourth Crusade (1202–1204), was redirected to Constantinople to intervene in a Byzantine succession dispute after the deposition of emperor Isaac II Angelos

- Loon War (1203–1206), after the death of Dirk VII, Count of Holland[2]

- War of the Moha succession (1212–1213), over the County of Moha after the death of count Albert II of Dagsburg

- First Barons' War (1215–1217). The war began as a Barons' revolt over king John Lackland's violation of the Magna Carta, but quickly turned into a dynastic war for the throne of England when French crownprince Louis became their champion, and John Lackland unexpectedly died

- War of the Succession of Champagne (1216–1222), indirectly after the death of count Theobald III of Champagne

- War of the Succession of Breda (1226/8–1231/2), after the death of lord Henry III of Schoten of Breda[75]

- War of the Flemish Succession (1244–1254), after the death of countess Joan of Constantinople of Flanders and Hainaut

- War of the Thuringian Succession (1247–1264), after the death of landgrave Henry Raspe IV of Thuringia

- Great Interregnum (1245/50–1273), after the deposition and death of emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire

- War of the Euboeote Succession (1256–1258), after the death of triarch Carintana dalle Carceri of Negroponte

- Castilian war of succession (1282–1304): after the death of crown prince Ferdinand de la Cerda (1275) and in anticipation of the death of king Alfonso X of Castile (1284), Ferdinand's brother Sancho proclaimed himself king in 1282, while Ferdinand's sons Alfonso de la Cerda and Ferdinand de la Cerda, Lord of Lara claimed to be the rightful heirs until they rescinded their claims in 1304[76]

- War of the Limburg Succession (1283–1288), after the death of duke Waleran IV and his daughter and heiress Irmgard of Limburg

Late Medieval Europe

- Scottish Wars of Independence (1296–1357), after the Scottish nobility requested king Edward I of England to mediate in the 1286–92 Scottish succession crisis, known as the "Great Cause". Edward would claim that his role in appointing the new king of Scots, John Balliol, meant that he was now Scotland's overlord, and started to interfere in Scottish domestic affairs, causing dissent.[77]

- First War of Scottish Independence (1296–1328), after Scottish opposition to Edward's interference reached the point of rebellion, Edward marched against Scotland, defeating and imprisoning John Balliol, stripping him off the kingship, and effectively annexing Scotland. However, William Wallace and Andrew Moray rose up against Edward and assumed the title of "guardians of Scotland" on behalf of John Balliol, passing this title on to Robert the Bruce (one of the claimants during the Great Cause) and John III Comyn in 1298. The former killed the latter in 1306, and was crowned king of Scots shortly after, in opposition to both Edward and the still imprisoned John Balliol.[77]

- Second War of Scottish Independence, or Anglo-Scottish War of Succession[78] (1332–1357), after the death of king of Scots Robert the Bruce

- Byzantine civil war of 1321–28, after the deaths of Manuel Palaiologos and his father, co-emperor Michael IX Palaiologos, and the exclusion of Andronikos III Palaiologos from the line of succession

- Bredevoorter Feud (1322–1326), after the death of count Herman II of Lohn

- Wars of the Rügen Succession (1326–1328; 1340–1354), after the death of prince Vitslav III of Rügen

- Serbian civil war of 1331, after king Stefan Uroš III of Serbia excluded his son Stefan Dušan from inheritance, leading the latter to rebel against his father

- Wars of the Loon Succession (1336–1366), after the death of count Louis IV of Loon

- Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), indirectly after the death of king Charles IV of France

- Galicia–Volhynia Wars (1340–1392), after the death of king Bolesław-Jerzy II of Galicia and Volhynia

- War of the Breton Succession (1341–1364), after the death of duke John III of Brittany

- Byzantine civil war of 1341–47, after the death of emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos

- Thuringian Counts' War (1342–1346), continuation of the War of the Thuringian Succession (1247–1264)

- Neapolitan campaigns of Louis the Great (1347–1352), after the assassination of Andrew, Duke of Calabria one day before his coronation as king of Naples

- Hook and Cod wars (1349–1490), after the death of count William IV of Holland

- Guelderian Fraternal Feud (1350–1361), after the death of duke Reginald II of Guelders

- Castilian Civil War (1351–1369), after the death of king Alfonso XI of Castile

- War of the Two Peters (1356–1375), spillover of the Castilian Civil War and Hundred Years' War

- War of the Valkenburg succession (1352–1365), after the death of lord John of Valkenburg[79]

- War of the Brabantian Succession (1355–1357), after the death of duke John III of Brabant

- Golden Horde Dynastic War (1359–1381)[80] after the assassination of khan Berdi Beg of the Golden Horde

- Fernandine Wars (1369–1382), fought over king Ferdinand I of Portugal's claim to the Castilian succession after the death of king Peter of Castile in 1369

- First Fernandine War (1369–1370)

- Second Fernandine War (1372–1373)

- Third Fernandine War (1381–1382)

- War of the Lüneburg Succession (1370–1389), after the death of duke William II of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- The three Guelderian wars of succession:

- First War of the Guelderian Succession (1371–1379), after the death of duke Reginald III of Guelders

- Second War of the Guelderian Succession (1423–1448), after the death of duke Reginald IV Guelders and Jülich

- Third War of the Guelderian Succession (1538–1543), see Guelders Wars (1502–1543)

- War of the Succession of the Patriarchate of Aquileia (1381–1388), after the death of patriarch Marquard of Randeck

- Greater Poland Civil War (1382–1385), after the death of king Louis the Hungarian of Poland

- 1383–1385 Portuguese interregnum, Portuguese succession crisis and war after the death of king Ferdinand I of Portugal

- Ottoman Interregnum (1401/2–1413), after the imprisonment and death of sultan Bayezid I

- Everstein Feud (1404–1409), after the childless count Herman VII of Everstein signed a treaty of inheritance with Simon III, Lord of Lippe, which was challenged by the Dukes of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Neapolitan war of succession (1420–1442), after the death of king Martin of Aragon (who also claimed Naples) and resulting from the childless queen Joanna II of Naples's subsequent conflicting adoptions of Alfonso V of Aragon, Louis III of Anjou and René of Anjou as her heirs

- Lithuanian Civil War (1432–38), after the death of grand duke Vytautas the Great of Lithuania

- Habsburg Dynastic War (1439–1457), after the death of Albert II of Germany[81]

- Old Zürich War (1440–1446), after the death of count Frederick VII of Toggenburg

- Saxon Fratricidal War (1446–1451), after the death of landgrave Frederick IV of Thuringia

- Milanese War of Succession (1447–1454), after the death of duke Filippo Maria Visconti of the Duchy of Milan[82][83]

- Navarrese Civil War (1451–1455), after the death of Blanche I of Navarre and the usurpation of the throne by John II of Aragon

- The Utrecht Civil Wars, related to the Hook and Cod wars.

- First Utrecht Civil War, after the death of bishop Rudolf van Diepholt of Utrecht

- Second Utrecht Civil War (1481–1483), spillover of the Hook and Cod wars

- Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), after the weakness of (and eventually the assassination of) king Henry VI of England

- War of the Neapolitan Succession (1458–1462), after the death of king Alfonso V of Aragon

- Skanderbeg's Italian expedition (1460–1462)

- War of the Succession of Stettin (1464–1529), after the death of duke Otto III of Pomerania

- Burgundian conquest of Guelders (1473), after the death of duke Arnold of Egmont of Guelders[84]

- War of the Castilian Succession (1475–1479), after the death of king Henry IV of Castile

- War of the Burgundian Succession (1477–1482), after the death of duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy

- Guelderian War of Independence (1477–1482, 1494–1499), after the death of duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy

- Ottoman war of succession (1481–1482), between prince Cem and prince Bayezid after the death of sultan Mehmet II

- Mad War or War of the Public Weal (1485–1488), about the regency over the underage king Charles VIII of France after the death of king Louis XI of France

- French–Breton War (1487–1491), anticipating the childless death of duke Francis II of Brittany (died 1488). Essentially, it was a resumption of the War of the Breton Succession (1341–1364)

- Jonker Fransen War (1488–1490), last ignition of the Hook and Cod wars

Early Modern Europe

- War of the Succession of Landshut (1503–1505), after the death of duke George of Bavaria-Landshut

- Ottoman Civil War (1509–13), between prince Selim and prince Ahmed about the succession of sultan Bayezid II (†1512)

- Danish Wars of Succession (1523–1537), a series of conflicts about the Danish throne within the House of Oldenburg

- Danish War of Succession (1523–1524), because of dissatisfaction about the kingship of Christian II of Denmark, who was deposed; indirectly caused by the death of king John (Hans) of Denmark in 1513 (see also Siege of Copenhagen (1523))

- Count's Feud (1534–1536), after the death of king Frederick I of Denmark

- Ottoman war of succession of 1559, between prince Selim and prince Bayezid about the succession of sultan Süleyman I

- Danzig rebellion (1575–1577), due to the disputed 1576 Polish–Lithuanian royal election

- War of the Portuguese Succession (1580–1583), after the death of king-cardinal Henry of Portugal

- Struggles for the kingship of France in the late French Wars of Religion (1585–1598), as the House of Valois was set to die out

- War of the Three Henrys (1585–1589), after the death of duke Francis of Anjou, the French heir-presumptive, and Protestant king Henry of Navarre's exclusion from the order of succession. Spain intervened in favour of the Catholic League, led by duke Henry of Guise. King Henry III of France was caught between the two.

- Henry IV of France's succession (1589–1594). King Henry of Navarre became king Henry IV of France after the death of both duke Henry of Guise and king Henry III of France. Spain continued to intervene, claiming the French throne for infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia instead.[86] To appease Catholics, Henry IV converted to Catholicism in 1593, under the condition that Protestants be tolerated; his kingship was increasingly recognised in France.

- Franco-Spanish War (1595–1598). King Henry IV of France, uniting French Protestants and Catholics, declared war on Spain directly to counter Spanish infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia's claim to the French throne.

- War of the Polish Succession (1587–88), after the death of king and grand duke Stephen Báthory of Poland–Lithuania

- Strasbourg Bishops' War (1592–1604), after the death of prince-bishop John IV of Manderscheid

- Time of Troubles (1598–1613), after the death of tsar Feodor I of Russia

- Polish–Muscovite War (1605–18) or the Dimitriads, during which three False Dmitrys, imposters claiming to be Feodor's rightful successor, were advanced by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- War of Deposition against Sigismund (1598–1599), after the death of king John III of Sweden

- Polish–Swedish War (1600–29), originated from the War of Deposition against Sigismund

- War of the Jülich Succession (1609–1614), after the death of duke John William of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

- Düsseldorf Cow War (1651), indirectly after the death of duke John William of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

- War of the Montferrat Succession (1613–1617), after the death of duke Francesco IV Gonzaga

- War of the Mantuan Succession (1627–1631), after the death of duke Vincenzo II Gonzaga

- Piedmontese Civil War (1639–1642), after the death of duke Victor Amadeus I of Savoy

- War of Devolution (1667–1668), after the death of king Philip IV of Spain

- Moscow uprising of 1682, after the death of tsar Feodor III of Russia

- Monmouth Rebellion (1685), after the death of king Charles II of England

- English or Palatinate War of Succession, or Nine Years' War (1688–1697), after the Glorious Revolution, and with the death of elector Charles II of the Palatinate as the indirect cause

- The Jacobite risings (1688–1746) that tried to undo the Glorious Revolution (partially caused by the birth of James Francis Edward Stuart), also called the War of the British Succession[87]

- Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691), war in Ireland between William III of Orange and James II Stuart (part of the English War of Succession)[88]

- Scottish Jacobite rising (1689–92), war in Scotland between William III of Orange and James II Stuart (part of the English War of Succession)

- Jacobite rising of 1715 (1715–1716), after the death of heiress-presumptive Sophia of Hanover and queen Anne of Great Britain

- Jacobite rising of 1745 (1745–1746), attempt to regain the throne by the last serious Jacobite pretender

- War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), after the death of king Charles II of Spain

- Civil war in Poland (1704–1706): during the Great Northern War (1700–1721), the Swedish army occupied much of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, dethroned king and grand duke Augustus II the Strong, and the pro-Swedish Warsaw Confederation convened a special Sejm which elected Stanisław Leszczyński as the new king and grand duke; however, the anti-Swedish Sandomierz Coalition rejected Augustus' dethronement and Leszczyński's election, and declared war on Sweden and the Warsaw Confederation.[89]

- War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720), after the death of 'sun king' Louis XIV of France

- War of the Polish Succession (1733–1738), after the death of king Augustus II the Strong of Poland

- War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), after the death of archduke Charles VI of Austria

- First Silesian War (1740–1742), Prussian invasion and ensuing Central European theatre of the war

- Second Silesian War (1744–1745), renewed Prussian invasion and continuation of First Silesian War

- Russo-Swedish War (1741–43), Swedish and Russian participation in the War of the Austrian Succession

- Jacobite rising of 1745, France provided limited support to Charles Edward Stuart's invasion of Great Britain

- War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–1779), after the death of elector Maximilian III Joseph of Bavaria

Modern Europe

- Russian interregnum of 1825 (1825–1826), after the death of tsar Alexander I of Russia, who had secretly changed the order of succession from his brother Constantine in favour of his younger brother Nicholas, neither of whom wanted to rule. Two related but different rebel movements arose to offer their solution to the succession crisis: the aristocratic Petersburg-based group favoured a constitutional monarchy under Constantine, the democratic Kiev-based group of Pavel Pestel called for the establishment of a republic.[90]

- Decembrist revolt (December 1825), by the aristocratic Decembrists in Saint Petersburg

- Chernigov Regiment revolt (January 1826), by the republican Decembrists in Ukraine

- Liberal Wars, also Miguelist War or Portuguese Civil War (1828–1834), after the death of king John VI of Portugal

- The Carlist Wars, especially the First. Later Carlist Wars were more ideological in nature (against modernism)

- First Carlist War (1833–1839), after the death of king Ferdinand VII of Spain

- Second Carlist War (1846–1849), a small-scale uprising in protest against the marriage of Isabella II with someone else than the Carlist pretender Carlos Luis de Borbón

- Third Carlist War (1872–1876), after the coronation of king Amadeo I of Spain

- Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), in which both Carlist and Bourbonist monarchists vied to restore the monarchy (abolished in 1931) in favour of their own dynasty

- Second Schleswig War (1864), partially caused by the death of king Frederick VII of Denmark

- Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), directly caused by the Spanish succession crisis following the Glorious Revolution of 1868

North and South America

- Andean conflict

- Mesoamerican conflict

- Hawaiian conflict

- European intercolonial conflict

- Tepanec war of succession (1426–1428), after the death of king Tezozomoc of Azcapotzalco; this led to the formation of the anti-Tepanec Triple Alliance, better known as the Aztec Empire[91]

- War of the Two Brothers, or Inca Civil War (1529–1532), after the death of emperor Huayna Capac of the Inca Empire

- King William's War (1688–1697), North American theatre of the Nine Years' War

- Queen Anne's War (1702–1713), North American theatre of the War of the Spanish Succession

- War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–1748), a pre-existing Anglo-Spanish conflict in the Americas subsumed into the War of the Austrian Succession

- King George's War (1746–1748), North American theatre of the War of the Austrian Succession

- Hawaiian war of succession (1782), after the death of king Kalaniʻōpuʻu of Hawaii

In fiction

- The Succession Wars, a wargame set in the BattleTech universe

- The Successions, civil wars over the monarchy of Andor in The Wheel of Time

- The books in George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire series and its TV adaptation, Game of Thrones feature the War of the Five Kings, based around five individuals' competing claims to the throne after the death of King Robert Baratheon. Another is the Targaryen war of succession, better known as the Dance of the Dragons.

- In J.R.R. Tolkien's fantasy world of Middle-earth, several wars of succession take place, such as:

- The Wars with Angmar (T.A. 861–1975), after King Eärendur of Arnor died in T.A. 861 and the kingdom was split between his three quarreling sons, founding the rival realms of Arthedain, Cardolan and Rhudaur. When the lines of Eärendur died out in Cardolan and Rhudaur, King Argeleb I of Arthedain intended to reunite Arnor in T.A. 1349 and was recognised by Cardolan, but then the Witch-king of Angmar intervened, annexed Rhudaur, ravaged Cardolan and besieged Arthedain's capital city of Fornost. In T.A. 1973–1975, Arthedain was finally destroyed; even though allied Men from Gondor and Elves from Lindon subsequently succeeded in defeating Angmar in the Battle of Fornost and driving out the Witch-king, the Kingdom of Arnor would never be restored until the dawn of the Fourth Age.

- Wars of Succession, a 2018 strategy video game developed by AGEod about the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1713) and the Great Northern War (1700–1721), 'most of which focused around the succession of Poland'.[92]

See also

- Carlism

- Conservative

- Legitimist

- Loyalism

- Ottoman dynasty § Succession practices (including royal fratricide)

- Political mutilation in Byzantine culture

- Reactionary

- Restoration (disambiguation)

- Royalism

Literature

- Kohn, George Childs (2013). Dictionary of Wars. Revised Edition. Londen/New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781135954949.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (ed.) (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598843361. Retrieved 16 December 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313335389. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

Notes

- In the strict sense, the Three Kingdoms Period didn't begin until 220, when the last Han emperor Xian was forced to abdicate by Cao Pi, who proclaimed himself emperor of the Wei dynasty. This claim was soon challenged by Liu Bei, who pretended to be the rightful successor to Xian, and crowned himself emperor of "Shu-Han" (221), and Sun Quan, who first received the title of "king of Wu" by Cao Pi before becoming the third claimant to the imperial title in 229. However, the dismemberment of the Chinese Empire by infighting warlords had already begun in 184, when the Yellow Turban Rebellion and the Liang Province Rebellion broke out. Although the former was put down, the latter was maintained, and the rebels continued to form a de facto autonomous state in Liang for two more decades. The emperorship itself was already in danger in 189 when, after the death of emperor Ling first the eunuchs and later Dong Zhuo seized control at the imperial court, against which the governors and nobility rose fruitlessly, before getting into combat with each other and setting up rival warlord states.

- Initially, William of Normandy was called William "the Bastard" by his opponents because he was an illegitimate son (bastard) of Robert I, and therefore some Norman noblemen rejected him as successor. Later, he became known as William "the Conqueror" when he also managed to enforce his claim to the English throne with the 1066 Norman invasion of England. William's reign in Normandy itself was not unopposed until 1060, despite being largely secured since 1047.

References

- (in German) Johannes Kunisch, Staatsverfassung und Mächtepolitik – Zur Genese von Staatenkonflikten im Zeitalter des Absolutismus (Berlin 1979), p. 16.

- (in Dutch) Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Ada". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

Nuyens, Willem Jan Frans (1873). Algemeene geschiedenis des Nederlandschen volks: van de vroegste tijden tot op onze dagen, Volumes 5-8. Amsterdam: C.L. van Langenhuysen. pp. 80–81. Retrieved 7 January 2017. - de Graaf, Ronald P. (2004). Oorlog om Holland, 1000-1375 (in Dutch). Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 310. ISBN 9789065508072. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- (in Dutch) Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "zwaardleen"; "spilleleen". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- (in German) Johannes Kunisch, La guerre – c’est moi! – Zum Problem der Staatenkonflikte im Zeitalter des Absolutismus, in: ders.: Fürst, Gesellschaft, Krieg – Studien zur bellizistischen Disposition des absoluten Fürstenstaates (Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 1992), p. 21–27.

- (in German) Heinz Duchhardt, Krieg und Frieden im Zeitalter Ludwigs XIV. (Düsseldorf 1987), p. 20.

- Robert I. Moore, The First European Revolution: 970-1215 (2000), p. 66. Wiley-Blackwell.

- (in German) Gerhard Papke, Von der Miliz zum Stehenden Heer – Wehrwesen im Absolutismus, in: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (publisher) Deutsche Militärgeschichte 1648–1939, Vol.1 (Munich 1983), p. 186f.

- (in German) Heinz Duchhardt, Krieg und Frieden im Zeitalter Ludwigs XIV. (Düsseldorf 1987), p. 17.

- Brougham, Henry (1845). "Lord Brougham's Political Philosophy". The Edinburgh Review. 81-82 (1–2): 11.

- Chandra, Satish (2005). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. 2. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 267–269. ISBN 9788124110669. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Markovits, Claude, ed. (2004) [First published 1994 as Histoire de l'Inde Moderne]. A History of Modern India, 1480–1950 (2nd ed.). London: Anthem Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-84331-004-4.

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (2014). The Incas. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 157. ISBN 9781118610596. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Gillespie (2013), p. 114–115.

- Mikaberidze (2011), p. 89–90.

- Mikaberidze (2011), p. xv.

- Jaques (2007) p. 631.

- Warder, Anthony Kennedy (1989). Indian Kavya Literature, Volume 2. p. 9–10. ISBN 9788120804470. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Kertai, David (2015). The Architecture of Late Assyrian Royal Palaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 75–76. ISBN 9780198723189. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Reddy, K. Krishna (2006). General Studies History 4 Upsc. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 43. ISBN 9780070604476. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- De Ruggiero, Paolo (2014). Mark Antony: A Plain Blunt Man. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9781473834569. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "eerste eeuw. §4.2 Politieke ontwikkelingen". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Lacey, James (2016). Great Strategic Rivalries: From the Classical World to the Cold War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9780190620462. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Gillespie, Alexander (2013). The Causes of War. Volume 1: 3000 BCE to 1000 CE. Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 9781782252085. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Gillespie (2013), p. 117.

- Matt Hollis, Ilkin Gambar, Officially Devin, Nolan Karimov, András Szente-Dzsida (31 October 2019). "Gokturk Empire - Nomadic Civilizations Documentary". Kings and Generals. YouTube. Retrieved 6 November 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Knechtges, David R.; Taiping, Chang (2014). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol.3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. Leiden: Brill. p. 1831–1832. ISBN 9789004271852. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Davidson, Ronald M. (2002). Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780231501026. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Tandle (2014), p. 247–248.

- Tandle, Sanjeevkumar (2014). Indian History (Ancient Period). Solapur: Laxmi Book Publication. p. 211. ISBN 9781312372115. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Mikaberidze (2011), p. xxxviii.

- Mikaberidze (2011), p. 786.

- May, Timothy (2013). The Mongol Conquests in World History. London: Reaktion Books. p. 73. ISBN 9781861899712. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Aiyangar, Sakkottai Krishnaswami (1921). South India and her Muhammadan Invaders. Oxford University Press. p. 96–97. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Jayapalan, N. (2001). History of India, from 1206 to 1773. Volume II. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 76. ISBN 9788171569281. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- Kohn (2013), p. 246.

- Kohn (2013), p. 76–77.

- Jayapalan (2001), p. 50.

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 100–102. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- Kallie Szczepanski (9 August 2016). "King Sejong the Great of Korea: Background - The Strife of Princes". Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Abazov, R. (2016). Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Central Asia. Springer. p. lxxii. ISBN 9780230610903. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Sen, Tansen (2016). "The Impact of Zheng He's Expeditions on Indian Ocean Interactions". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 79 (3): 614–615. doi:10.1017/S0041977X16001038.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finkel, Caroline (2012). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1923. London: Hachette UK. p. 141–142. ISBN 9781848547858. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Woods, John E. (1999) The Aqquyunlu: Clan, Confederation, Empire, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, p. 125, ISBN 0-87480-565-1

- Jayapalan (2001), p. 102.

- May (2013), p. 95.

- James Macnabb Campbell, ed. (1896). "II. ÁHMEDÁBÁD KINGS. (A. D. 1403–1573.)". History of Gujarát. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Volume I. Part II. The Government Central Press. pp. 253–254.

- Jaques (2007), p. 499.

- Mikaberidze (2011), p. 698.

- Richards (2001), p. 94.

- Vriddhagirisan, V. (1995). The Nayaks of Tanjore. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 49–71, 118. ISBN 9788120609969. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Richards, John F. (2001). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780521566032. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Mullard, Saul (2011). Opening the Hidden Land: State Formation and the Construction of Sikkimese History. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. p. 161–164. ISBN 9789004208957. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Kohn (2013), p. 56.

- Mikaberidze (2011), p. 408–409.

- Richards (2001), p. 204.

- Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). History of Tipu Sultan. Delhi: Aakar Books. p. 276. ISBN 9788187879572. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Mikaberidze (2011), p. lix.

- Kohn (2013), p. 5.

- Gibson, Thomas (2007). Islamic Narrative and Authority in Southeast Asia: From the 16th to the 21st Century. New York: Springer. p. 117. ISBN 9780230605084. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Menke de Groot. "Boni-expedities van 1859-1860". Expedities van het KNIL (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Hampson, Robert (2012). Conrad's Secrets. London: Springer. pp. 36–37. ISBN 9781137264671. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- (in Dutch) Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Lodewijk [Frankische, Roomse en (Rooms-)Duitse koningen en keizers]. §1. Lodewijk I".

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 141.

- Kohn (2013), p. 587.

- Timothy Reuter (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History. Volume 3, c.900–c.1024 (1999), p. 321.

- Jaques (2007), p. 441.

- Douglas, David C. (1964). William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 51. OCLC 399137.

- Aird, William M. (2011). Robert `Curthose', Duke of Normandy (C. 1050-1134). p. 41–47. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Jessee, W. Scott (2000). Robert the Burgundian and the Counts of Anjou, Ca. 1025-1098. p. 56–57. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Van Antwerp Fine, Jr., John (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 3–4. ISBN 9780472082605. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Namen [geschiedenis]. §1. Regeerders". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Coppens, Thera (2019). Johanna en Margaretha: Gravinnen van Vlaanderen en prinsessen van Constantinopel. Meulenhoff Boekerij. p. 348, footnote 315. ISBN 9789402313956. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Seel, Graham E. (2012). King John: An Underrated King. London: Anthem Press. p. 39–52. ISBN 9780857282392. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Boeren, P.C. (1962). Hadewych en Heer Hendrik Van Breda (in Dutch). Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 28–29. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- Emmerson, Richard K. (2013). Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 592–593. ISBN 9781136775192. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "The Wars of Independence". Scotland's History. BBC Scotland. 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Jaques (2007), p. 530.

- Boffa (2004), p. 13–15.

- Kohn (2013), p. 587.

- Kohn (2013), p. 206.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A-E. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. xxxiii, 153, 200. ISBN 9780313335372. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Ady, Cecilia M. and Edward Armstrong (1907). A History of Milan under the Sforza. Methuen & Co. p. 70.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Karel [Bourgondische gewesten]. §1. Buitenlandse politiek". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Oostenrijkse Successieoorlog".

- "Isabella Clara Eugenia, archduchess of Austria". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 6 November 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Black, Jeremy (2015). A Short History of Britain. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 49–50. ISBN 9781472586681. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Kohn (2013), p. 162.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2008). Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization. London: Greenwood Press. p. 186. ISBN 9780313359200. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Kohn (2013), p. 146.

-

- Smith, Michael (2009). The Aztecs, 2nd Edition. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 0-631-23015-7.

- AGEod (25 January 2018). "Wars of Succession on Steam". Steam. Slitherine Ltd. Retrieved 13 December 2019.