Yazdegerd II

Yazdegerd II (also spelled Yazdgerd II and Yazdgird II; Middle Persian: 𐭩𐭦𐭣𐭪𐭥𐭲𐭩), was the sixteenth Sasanian king (shah) of Iran. He was the successor and son of Bahram V (r. 420–438) and reigned from 438 to 457. His reign was marked by wars against the Eastern Roman Empire in the west and the Hephthalites in the east, as well as by his efforts and attempts to strengthen royal centralisation in the bureaucracy by imposing Zoroastrianism on the non-Zoroastrians within the country, namely the Christians. His death led to a dynastic struggle between his two sons Hormizd III and Peroz I for the throne, with the latter emerging victorious.

| Yazdegerd II 𐭩𐭦𐭣𐭪𐭥𐭲𐭩 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings of Iran and Aniran | |

| |

| Shahanshah of the Sasanian Empire | |

| Reign | 438 – 457 |

| Predecessor | Bahram V |

| Successor | Hormizd III |

| Died | 457 |

| Consort | Denag |

| Issue | Hormizd III Peroz I Balash Zarir |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Bahram V |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Yazdegerd II was the first Sasanian ruler to assume the title of kay, which evidently associates him and the dynasty to the mythical Kayanian dynasty commemorated in the Avesta.

Etymology

The name of Yazdegerd is a combination of the Old Iranian yazad yazata- "divine being" and -karta "made", and thus stands for "God-made", comparable to Iranian Bagkart and Greek Theoktistos.[1] The name of Yazdegerd is known in other languages as; Pahlavi Yazdekert; New Persian Yazd(e)gerd; Syriac Yazdegerd, Izdegerd, and Yazdeger; Armenian Yazdkert; Talmudic Izdeger and Azger; Arabic Yazdeijerd; Greek Isdigerdes.[1]

Wars

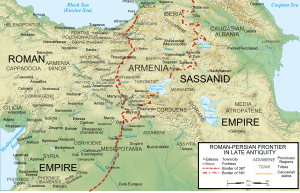

In 438, shah Bahram V (r. 420–438) died, and was succeeded by Yazdegerd II. His western neighbours, the Romans, had since their peace treaty with Iran in 387 agreed that both empires were obligated to cooperate in the defense of the Caucasus against nomadic attacks.[2] The Romans helped in the defense of the Caucasus by paying the Iranians roughly 500 lbs (226 kg) of gold at irregular intervals.[3] While the Romans saw this payment as political subsidies, the Iranians saw it as tribute, which proved that Rome was the deputy of Iran.[4] The Roman emperor Theodosius II's unwillingness to continue the payment made Yazdegerd II declare war against the Romans,[4][2] which had ultimately little success for either side.[5]

The Romans were invaded in their southern provinces by the Vandals, causing Theodosius II to ask for peace and send his commander, Anatolius, personally to Yazdegerd II's camp.[6] In the ensuing negotiations in 440, both empires promised not to build any new fortifications in Mesopotamia and that the Sasanian Empire would get some payment in order to protect the Caucasus from incursions.[5] Shortly after his peace treaty with the Romans, Yazdegerd II moved towards the important Sasanian province of Armenia and defeated the Armenians, capturing nobles, priests, and troops; and sending them to the eastern Sasanian provinces to protect the borders from Hephthalite attacks.[5] In the 440s, Yazdegerd II had a mudbrick defensive system constructed at Derbent to fend off incursions from the north.[7]

In 453, Yazdegerd II moved his court to Nishapur in Khorasan to face the threat from the Hephthalites and left his minister (wuzurg framadar) Mihr Narseh in charge of the Sasanian Empire.[8] He spent many years at war against the Hephthalites.[5] According to the Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr ("The Provincial Capitals of Iran"), Yazdegerd II fortified the city of Damghan and turned it into a strong border post against the Hephthalites.[5] It was sometime during this period that Yazdegerd II created the province of Eran-Khwarrah-Yazdegerd ("Iran, glory of Yazdegerd"), which was in the northern part of the Gurgan province.[9] After he managed to secure the eastern portion of his empire against the Hephthalite incursions, Yazdegerd II shifted his focus on Armenia and Caucasian Albania to defend the Caucasus with the Romans against the increasing Hun threat.[10]

Religious policy

The policies of Yazdegerd II have been the matter of discussion; Arabic and Persian sources emphasize his personal piety and hostility towards the aristocracy, whilst Armenian and Syriac sources describe him as a religious fanatic. The latter aspect is often stressed in modern historiography.[11] The unsteadiness of the empire was ever increasing under Yazdegerd II, who had an uneasy relationship with the aristocracy and was facing a great challenge by the Hephthalites in the east.[11] At the beginning of Yazdegerd II's reign, he suffered several defeats at the hands of the Hephthalites, for which he put the blame on the Christians, due to much of his cavalry consisting of Iberians and Armenians.[11] Persecutions of Christians first started in 446 with the Christian nobles of Karkh in Mesopotamia.[11] He later shifted his focus towards the Christian aristocracy of Iberia and Armenia.[11] Yazdegerd II's persecutions of non-Zoroastrians generally seem to have been limited, with the aristocracy being the primary target.[11] Indeed, Zoroastrian aristocrats were also targeted by Yazdegerd II, who had the advantage of entry to the court dismantled and castrated men in his field armies to generate eunuchs more dutiful to him than to their own families.[12]

Yazdegerd II had originally continued his father's policies of appeasing the magnates. However, after some time, he turned away from them and started a policy of his own. When the magnates told him that his new policies had offended the people, he disagreed, saying that: "it is not correct for you to presume that the ways in which my father behaved towards you, maintaining you close to him, and bestowing upon you all that bounty, are incumbent upon all the kings that come after him ... each age has its own customs."[13] Yazdegerd II, however, was still fully aware of the longstanding conflict between the crown and the nobility and priesthood, which had culminated in the murder of several Sasanian monarchs.[14]

Yazdegerd II's primary goal throughout his reign was thus to combat the internal and external issues posing a danger to country by strengthening the royal centralisation of the bureaucracy, which demanded the cooperation of the aristocracy.[11] The justification behind this is later apparent when Yazdegerd II appointed Adhur-Hormizd as the new governor (marzban) of Armenia in 451, putting an end to the persecution of non-Zoroastrians in Armenia and allowing religious freedom in the country.[15] This would have been an unlikely decision to have been made by a religious fanatic.[16] Indeed, according to the modern historian Scott McDonough, the Zoroastrian faith was perhaps a "test of personal loyalty" for Yazdegerd II.[16] However, Yazdegerd II's policy of integrating the Christian nobility into the bureaucracy still had problematic consequences; before the appointment of Adhur-Hormizd, Armenia had been plunged into a major rebellion.[11][5] The cause of the rebellion was the attempt of Mihr Narseh to impose the Zurvanite variant of Zoroastrianism in Armenia.[11] His intentions differed from those of Yazdegerd II.[16] As a result, many of the Armenian nobles (but not all) rallied under Vardan Mamikonian, the supreme commander (sparapet) of Armenia.[17] The Armenian rebels tried to appeal to the Romans for help, but to no avail.[18] Meanwhile, another faction of Armenians, led by the marzban Vasak Siwni allied themselves with the Sasanians.[17]

On 2 June 451, the Sasanian and rebel forces clashed at Avarayr, with the Sasanians emerging victorious.[18] Nine generals, including Vardan Mamikonian, were killed, with a large number of the Armenian nobles and soldiers meeting the same fate.[18] The Sasanians, however, had also suffered heavy losses due to the resolute struggle by the Armenian rebels.[18] Although Yazdegerd II put an end to the persecutions in the country afterwards, tensions continued until 510 when a kinsman of Vardan Mamikonian, Vard Mamikonian, was appointed marzban by Yazdegerd II's grandson, Kavad I (r. 488–531).[19]

Jews were also the subject of persecution under Yazdegerd II; he is said to have issued decrees prohibiting them from observing the Sabbath openly,[20] and ordered executions of several Jewish leaders.[5] This resulted in the Jewish community of Spahan publicly retaliating by flaying two Zoroastrian priests alive, leading in turn to more persecutions against the Jews.[5]

Personality

Yazdegerd II was an astute and well-read ruler whose motto was "Question, examine, see. Let us choose and hold that which is best."[21] He is generally praised in Persian sources, and is described as a compassionate and benevolent ruler.[22] He is commended for abandoning his father's overindulgence in hunting, feasting, and having long audience sessions.[23][5] According to the medieval historians Ibn al-Balkhi and Hamza al-Isfahani, he was known as "Yazdegerd the Gentle" (Yazdegerd-e Narm).[5] However, the favorable account of Yazdegerd II is due to his policy of persecuting non-Zoroastrians within the empire, which appeased the Iranian aristocracy and especially the Zoroastrian priesthood, which sought to use the Sasanian Empire to impose their authority over the religious and cultural life of its people.[23] This is the opposite of the policy of his grandfather and namesake, Yazdegerd I (known as the "sinner"), who is the subject of hostility in Persian sources due to his tolerant policy towards his non-Zoroastrian subjects, and his refusal to comply with the demands of the aristocracy and priesthood.[24]

Coin mints and imperial ideology

The reign of Yazdegerd II marks the start of a new inscription on the Sasanian coins; mzdysn bgy kdy ("The Mazda-worshipping majesty, the Kayanian"), which displays his fondness of the legendary Avestan dynasty, the Kayanians.[5][lower-alpha 1] This is due to a shift in the political perspective of the Sasanian Empire−originally disposed towards the West, was now changed to the East.[26] This shift, which had already started under Yazdegerd I and Bahram V, reached its zenith under Yazdegerd II.[26] It may have been triggered due to the advent of hostile tribes on the eastern front of Iran.[26] The war against the Hephthalites may have awakened the mythical rivalry existing between the Iranian Kayanian rulers and their Turanian enemies, which is demonstrated in the Younger Avesta.[26] It may have thus been as a result of the conflict between Iran and its eastern enemies, that resulted in the adoption of the title of kay, used by the very same Iranian mythical kings in their war against the Turanians in the East.[26]

Likewise, it was most likely during this period that legendary and epic texts were collected by the Sasanians, including the legend of the Iranian hero-king Fereydun (Frēdōn in Middle Persian), who split up his kingdom among his three sons; his eldest son Salm receiving the empire of the West, Rome; the second eldest Tur receiving the empire of the East, Turan; and the youngest Iraj receiving the heartland of the empire, Iran.[26] Accordingly, influenced by the texts about the Kayanians, Yazdegerd II may believed to be the heir of the Fereydun and Iraj, thus possibly deeming not only Roman domains in West as belonging to Iran, but also the eastern domains of the Hephthalites.[26] Thus the Sasanians may have sought to symbolically assert their rights over those lands by assuming the Kayanian title of kay.[26]

A new design also appeared on the reverse of the Sasanian coins, where the traditional fire altar flanked by two attendants, now imitates them in a more venerated manner.[5] This presumably further demonstrates Yazdegerd II's fealty to Zoroastrianism.[5] The provinces of Asoristan and Khuzestan provided the most mints for Yazdegerd II in the west, whilst the provinces of Gurgan and Marw provided the most in the east, undoubtly to support the Sasanians in their wars on the two fronts.[5]

Death and succession

Yazdegerd II died in 457; his eldest son Hormizd III ascended the throne at Ray.[27] His younger son Peroz I, with the support of the powerful Mihranid magnate Raham Mihran, fled to the northeastern part of the empire and began raising an army in order to claim the throne for himself.[27][28] The empire thus fell into a dynastic struggle and became divided. The mother of the two brothers, Denag, temporarily ruled as regent of the empire from its capital, Ctesiphon.[27]

Family

Marriages

- Denag, an Iranian princess, possibly from the royal Sasanian family.

Issue

- Hormizd III, seventeenth shah of the Sasanian Empire (r. 457–459).

- Peroz I, eighteenth shah of the Sasanian Empire (r. 459–484).

- Zarir, Sasanian prince, who tried to claim the throne by rebelling in 485.

- Balash, nineteenth shah of the Sasanian Empire (r. 484–488).

Notes

- The title of kay had already been in use at least 100 years earlier by the Kushano-Sasanians, a cadet branch of the imperial Sasanian family that ruled in the East before being supplanted by the Kidarites and the imperial Sasanians in the mid 4th-century.[25]

References

- Shahbazi 2003.

- Shayegan 2017, p. 809.

- Payne 2015b, pp. 296-298.

- Payne 2015b, p. 298.

- Daryaee.

- Frye 1983, p. 146.

- Gadjiev 2017, p. 122.

- Daryaee 2000.

- Gyselen 1998, p. 537.

- Daryaee 2014, p. 23.

- Sauer 2017, p. 192.

- Payne 2015a, p. 46.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 70.

- Kia 2016, pp. 281-282.

- Sauer 2017, pp. 192-193.

- Sauer 2017, p. 193.

- Avdoyan 2018.

- Hewsen 1987, p. 32.

- Nersessian 2018.

- Gaon 1988, p. 115.

- Shahbazi 2005.

- Kia 2016, p. 282.

- Kia 2016, p. 283.

- Kia 2016, pp. 282-283.

- Rezakhani 2017, pp. 79, 83.

- Shayegan 2017, p. 807.

- Kia 2016, p. 248.

- Pourshariati 2008, p. 71.

Sources

- Avdoyan, Levon (2018). "Avarayr, Battle of (Awarayr)". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj (2000). "Mehr-Narseh". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daryaee, Touraj. "Yazdegerd II". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frye, R. N. (1983). "The political history of Iran under the Sasanians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Gadjiev, Murtazali (2017). Construction Activities of Kavād I in Caucasian Albania. Brill. pp. 121–131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaon, Sherira (1988). The Iggeres of Rav Sherira Gaon. Translated by Nosson Dovid Rabinowich. Jerusalem: Rabbi Jacob Joseph School Press - Ahavath Torah Institute Moznaim. OCLC 923562173.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gyselen, Rika (1998). "Ērān-Xwarrah-Yazdgerd". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. p. 537.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hewsen, R. (1987). "Avarayr". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 1. p. 32.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nersessian, Vrej (2018). "Persarmenia". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Payne, Richard E. (2015a). A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Univ of California Press. pp. 1–320. ISBN 9780520961531.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Payne, Richard (2015b). "The Reinvention of Iran: The Sasanian Empire and the Huns". In Maas, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge University Press. pp. 282–299. ISBN 978-1-107-63388-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (registration required)

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sauer, Eberhard (2017). Sasanian Persia: Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. London and New York: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–336. ISBN 9781474401029.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2003). "Yazdegerd I". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2017). "Sasanian political ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–1021. ISBN 9780190668662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2018). "Yazdegerd II". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192562463.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Yazdegerd II | ||

| Preceded by Bahram V |

King of kings of Iran and Aniran 438 – 457 |

Succeeded by Hormizd III |