Succession to Muhammad

The succession to Muhammad is the central issue that split the Muslim community into several divisions in the first century of Islamic history, with the most prominent among these sects being the Shia and Sunni branches of Islam. Shia Islam holds that Ali ibn Abi Talib was the appointed successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad as head of the community. Sunni Islam maintains Abu Bakr to be the first leader after Muhammad on the basis of election.

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

|

|

Views |

|

Related |

|

The contrasting opinions regarding the succession are primarily based on differing interpretations of events in early Islamic history as well as of hadiths (sayings of Muhammad). Sunnis believe that Muhammad had no appointed successor and had instead intended that the Muslim community choose a leader from among themselves. They accept the rule of Abu Bakr, who was elected at Saqifah, and that of his successors, who are together termed the Rashidun Caliphs. Conversely, Shi'ites believe that Ali had previously been nominated by Muhammad as heir, most notably during the Event of Ghadir Khumm. They primarily see the rulers who followed Muhammad as illegitimate, with the only rightful Muslim leaders being Ali and his lineal descendants, the Twelve Imams, who are viewed as divinely appointed.

In addition to these two main views, there are also other opinions regarding the succession to Muhammad.

Historiography

Most of Islamic history was transmitted orally until after the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate.[note 1] Historical works of later Muslim writers include the traditional biographies of Muhammad and quotations attributed to him—the sira and hadith literature—which provide further information on Muhammad's life.[1] The earliest surviving written sira (biography of Muhammad) is Sirat Rasul Allah (Life of God's Messenger) by Ibn Ishaq (d. 761 or 767 CE).[2] Although the original work is lost, portions of it survive in the recensions of Ibn Hisham (d. 833) and Al-Tabari (d. 923).[3] Many scholars accept these biographies although their accuracy is uncertain.[4] Studies by J. Schacht and Ignác Goldziher have led scholars to distinguish between legal and historical traditions. According to William Montgomery Watt, although legal traditions could have been invented, historical material may have been primarily subject to "tendential shaping" rather than being invented.[5] Modern Western scholars approach the classic Islamic histories with circumspection and are less likely than Sunni Islamic scholars to trust the work of the Abbasid historians.

Hadith compilations are records of the traditions or sayings of Muhammad. The development of hadith is a crucial element of the first three centuries of Islamic history.[6] Early Western scholars mistrusted the later narrations and reports, regarding them as fabrications.[7] Leone Caetani considered the attribution of historical reports to `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas and Aisha as mostly fictitious, preferring accounts reported without isnad by early historians such as Ibn Ishaq.[8] Wilferd Madelung has rejected the indiscriminate dismissal of everything not included in "early sources", instead judging later narratives in the context of history and compatibility with events and figures.[9]

The only contemporaneous source is The Book of Sulaym ibn Qays (Kitab al-Saqifah) by Sulaym ibn Qays (died 75-95 AH or 694-714 CE). This collection of hadith and historical reports from the first century of the Islamic calendar narrates in detail events relating to the succession.[10] However, there have been doubts regarding the reliability of the collection, with some believing that it was a later creation given that the earliest mention of the text only appears in the 11th century.[11]

Hadiths

Feast of Dhul Asheera

During the revelation of Ash-Shu'ara, the twenty-sixth Surah of the Quran, in c. 617,[12] Muhammad is said to have received instructions to warn his family members against adhering to their pre-Islamic religious practices. There are differing accounts of Muhammad's attempt to do this, with one version stating that he had invited his relatives to a meal (later termed the Feast of Dhul Asheera), during which he gave the pronouncement.[13] According to Ibn Ishaq, it consisted of the following speech:

Allah has commanded me to invite you to His religion by saying: And warn thy nearest kinsfolk. I, therefore, warn you, and call upon you to testify that there is no god but Allah, and that I am His messenger. O ye sons of Abdul Muttalib, no one ever came to you before with anything better than what I have brought to you. By accepting it, your welfare will be assured in this world and in the Hereafter. Who among you will support me in carrying out this momentous duty? Who will share the burden of this work with me? Who will respond to my call? Who will become my vicegerent, my deputy and my wazir?[14]

Among those gathered, only Ali offered his consent. Some sources, such as the Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal, do not record Muhammad's reaction to this, though Ibn Ishaq continues that he then declared Ali to be his brother, heir and successor.[15] In another narration, when Muhammad accepted Ali's offer, he "threw up his arms around the generous youth, and pressed him to his bosom" and said, "Behold my brother, my vizir, my vicegerent ... let all listen to his words, and obey him."[16]

The direct appointment of Ali as heir in this version is notable by the fact it alleges that his right to succession was established at the very beginning of Muhammad's prophetic activity. The association with the revelation of a Quranic verse also serves the purpose of providing the nomination with authenticity as well as a divine authorisation.[17]

Muhammad not naming a successor

A number of sayings attributed to prominent companions of Muhammad are compiled by Al-Suyuti in his Tarikh Al Khulafa, which are used to present the view that Muhammad had not named a successor.[18] One such example, narrated by Al-Bayhaqi, alleges that Ali, following his victory in the Battle of the Camel, gave the statement "Oh men, verily the Apostle of God (Muhammad) hath committed nothing unto us in regard to this authority, in order that we might of our own judgement approve and appoint Abu Bakr." Another, recorded by Al-Hakim Nishapuri and also accredited to Ali, states that when asked if he wished to name his successor as caliph, Ali responded "the Apostle of God appointed none, shall I therefore do so?"[19] It is also claimed that when Caliph Umar was asked the same question, he replied that if he gave a nomination, he had precedent in Abu Bakr's actions; if he named no one, he had precedent by Muhammad's.[18]

Hadith of Position

Prior to embarking on the Expedition to Tabuk in 631, Muhammad designated Ali to remain in Medina and govern in his absence. According to Ibn Hisham, one of the earliest available sources of this hadith, Ali heard suggestions that he had been left behind because Muhammad had found his presence a burden. Ali immediately took his weapons and followed in pursuit of the army, catching up with them in an area called al-Jurf. He relayed to Muhammad the rumours, to which the latter responded "They lie. I left you behind because of what I had left behind, so go back and represent me in my family and yours. Are you not content, Ali, to stand to me as Aaron stood to Moses, except that there will be no prophet after me?" Ali then returned to Medina and took up his position as instructed.[20]

The key part of this hadith (in regards to the Shia interpretation of the succession) is the comparison of Muhammad and Ali with Moses and his brother Aaron. Aside from the fact that the relationship between the latter two is noted for its special closeness, hence emphasising that of the former,[21] it is notable that in Muslim traditions, Aaron was appointed by God as Moses' assistant, thus acting as an associate in his prophetic mission.[22] In the Quran, Aaron was described as being his brother's deputy when Moses ascended Mount Sinai.[23][24] This position, the Shia scholar Sharif al-Murtaza argues, shows that he would have been Moses' successor and that Muhammad, by drawing the parallel between them, therefore viewed Ali in the same manner.[22] Of similar importance is the divine prerogatives bestowed upon Aaron's descendants in Rabbinical literature, whereby only his progeny is permitted to hold the priesthood. This can be compared to the Shia belief in the Imamate, in which Ali and his descendants are regarded as inheritors of religious authority.[25]

However, there are a number of caveats against this interpretation. The scholar al-Halabi records a version of the hadith which includes the additional detail that Ali had not been Muhammad's first choice in governing Medina, having instead initially chosen an individual named Ja'far.[note 2] It was only on the latter's refusal that Ali was given the position.[26] It is also notable that the familial relationship between Moses and Aaron was not the same as that of Muhammad and Ali, given that one pair were brothers while the other were cousins/in-laws.[27] Additionally, the Quran records that Aaron had failed in his duties during his brother's absence, having not only been unable to properly guide the people, but also joining them in performing idolatry.[28][29][27] Finally, Aaron never succeeded his brother, having died during Moses' lifetime after being punished by God for the latter's mistakes.[27]

Event of Ghadir Khumm

The hadith of Ghadir Khumm has many different variations and is transmitted by both Sunni and Shia sources. The narrations generally state that in March 632, Muhammad, while returning from his Farewell Pilgrimage alongside a large number of followers and companions, stopped at the oasis of Ghadir Khumm. There, he took Ali's hand and addressed the gathering. The point of contention between different sects is when Muhammad, whilst giving his speech, gave the proclamation "Anyone who has me as his mawla, has Ali as his mawla." Some versions add the additional sentence "O God, befriend the friend of Ali and be the enemy of his enemy."[30]

Mawla has a number of meanings in Arabic, with interpretations of Muhammad's use here being split along sectarian lines between the Sunni and Shia. Among the former group, the word is translated as "friend" or "one who is loyal/close" and that Muhammad was advocating that Ali was deserving of friendship and respect. Conversely, Shi'ites tend to view the meaning as being "master" or "ruler"[31] and that the statement was a clear designation of Ali being Muhammad's appointed successor.[30]

Shia sources also record further details of the event. They state that those present congratulated Ali and acclaimed him as Amir al-Mu'minin, while Ibn Shahr Ashub reports that Hassan ibn Thabit recited a poem in his honour.[30] However, some doubts have been raised about this view of the incident. Historian M. A. Shaban argues that sources regarding the community at Medina at the time give no indication of the expected reaction had they heard of Ali's appointment.[32] Ibn Kathir meanwhile suggests that Ali was not present at Ghadir Khumm, instead being stationed in Yemen at the time of the sermon.[33]

Supporting Abu Bakr's succession

Among Sunni sources, Abu Bakr's succession is justified by narrations of Muhammad displaying the regard with which he held the former. The most notable of these incidents occurred towards the end of Muhammad's life. Too ill to lead prayers as he usually would, Muhammad had instructed that Abu Bakr instead take his place, ignoring concerns that he was too emotionally delicate for the role. Abu Bakr subsequently took up the position, and when Muhammad entered the prayer hall one morning during Fajr prayers, Abu Bakr attempted to step back to let him to take up his normal place and lead. Muhammad however, allowed him to continue.[34]

Other incidents similarly used by Sunnis were Abu Bakr serving as Muhammad's vizier during his time in Medina, as well as him being appointed the first of his companions to lead the Hajj pilgrimage. However, several other companions had held similar positions of authority and trust, including the leading of prayers. Such honours may therefore not hold much importance in matters of succession.[34][32]

Incident of the pen and paper

Shortly before his death, Muhammad asked for writing materials so as to issue a statement that would prevent the Muslim nation from "going astray forever".[35][36] However, those in the room began to quarrel about whether to obey this request, with concerns being raised that Muhammad may be suffering from delirium. When the argument grew heated, Muhammad ordered the group to leave and subsequently chose not to write anything.[37]

Many details regarding the event are disputed, including the nature of Muhammad's planned statement. Though what he had intended to write is unknown, later theologians and writers have offered their own suggestions, with many believing that he had wished to establish his succession. Shia writers, like Al-Shaykh Al-Mufid, suggest that it would have been a direct appointment of Ali as the new leader, while Sunnis, such as Al-Baladhuri, state that it was to designate Abu Bakr. The story has also been linked to the rise of the community politics which followed Muhammad's death, with a possible suggestion that the hadith shows that Muhammad had implicitly given his acceptance and permission to how the Muslim ummah chooses to act in his absence. It may therefore be linked with the emergence of sayings attributed to Muhammad such as "My ummah will never agree on an error", an idea perpetuated by theologians like Ibn Hazm and Ibn Sayyid al-Nās.[37]

Historical overview

Saqifah

In the immediate aftermath of the death of Muhammad in 632, a gathering of the Ansar (natives of Medina) took place in the Saqifah (courtyard) of the Banu Sa'ida clan.[38] The general belief at the time was that the purpose of the meeting was for the Ansar to decide on a new leader of the Muslim community among themselves, with the intentional exclusion of the Muhajirun (migrants from Mecca), though this has since become the subject of debate.[39]

Nevertheless, Abu Bakr and Umar, both prominent companions of Muhammad, upon learning of the meeting became concerned of a potential coup and hastened to the gathering. When they arrived, Abu Bakr addressed the assembled men with a warning that an attempt to elect a leader outside of Muhammad's own tribe, the Quraysh, would likely result in dissension, as only they can command the necessary respect among the community. He then took Umar and another companion, Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah, by the hand and offered them to the Ansar as potential choices. He was countered with the suggestion that the Quraysh and the Ansar each choose a leader from among themselves, who would then rule jointly. The group grew heated upon hearing this proposal and began to argue amongst themselves. Umar hastily took Abu Bakr's hand and swore his own allegiance to the latter, an example followed by the gathered men.[40]

Abu Bakr was near-universally accepted as head of the Muslim community as a result of Saqifah, though he did face contention as a result of the rushed nature of the event. Several companions, most prominent among them being Ali ibn Abi Talib, initially refused to acknowledge his authority.[38] Ali himself may have been reasonably expected to assume leadership upon Muhammad's death, having been both the latter's cousin and son-in-law.[41] The theologian Ibrahim al-Nakhai stated that Ali also had support among the Ansar for his succession, explained by the genealogical links he shared with them.[note 3] Whether his candidacy for the succession was raised during Saqifah is unknown, though it is not unlikely.[43] Abu Bakr later sent Umar to confront Ali to gain his allegiance, resulting in an altercation which may have involved violence.[44] Six months after Saqifah, the dissenting group made peace with Abu Bakr and Ali offered him his fealty.[45] However, this initial conflict is regarded as the first sign of the coming split between the Muslims.[46] Those who had accepted Abu Bakr's election later became the Sunnis, while the supporters of Ali's hereditary right eventually became the Shia.[47]

Subsequent succession

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

Main caliphates |

|

Parallel caliphates |

|

|

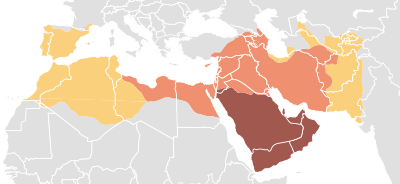

Abu Bakr adopted the title of Khalifat Rasul Allah, generally translated as "Successor to the Messenger of God".[48] This was shortened to Khalifa, from which the word "Caliph" arose. The use of this title continued with Abu Bakr's own successors, the caliphs Umar, Uthman and Ali, all of whom were non-hereditary.[49][50] This was a group referred to by Sunnis as the Rashidun (rightly-guided) Caliphs, though only Ali is recognised by the Shia.[41] Abu Bakr's argument that the caliphate should reside with the Quraysh was accepted by nearly all Muslims in later generations. However, after Ali's assassination in 661, this definition also allowed the rise of the Umayyads to the throne, who despite being members of the Quraysh, were generally late converts to Islam during Muhammad's lifetime.[51]

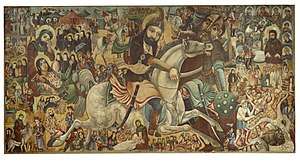

Their ascendancy had been preceded by a civil war among the Sunnis and Shi'ites known as the First Fitna. Hostilities only ceased when Ali's eldest son Hasan (who had been elected upon his father's death)[52] made an agreement to abdicate in favour of the first Umayyad caliph, Muawiyah I, resulting in a period of relative calm and a hiatus in sectarian disagreements. This ended upon Muawiyah's death after twenty years of rule, when rather than following the previous tradition of electing/selecting a successor from among the pious community, he nominated his own son Yazid. This hereditary process of succession angered Hasan's younger brother Husayn, who publicly denounced the new caliph's legitimacy. Husayn and his family were eventually killed by Yazid's forces in 680 during the Battle of Karbala. This conflict marked the Second Fitna, as a result of which the Sunni-Shia schism became finalised.[50]

The succession subsequently transformed under the Umayyads from an elective/appointed position to being effectively hereditary within the family,[53] leading to the complaint that the caliphate had become no more than a "worldly kingship."[51] The Shi'ite's idea of the succession to Muhammad similarly evolved over time. Initially, some of the early Shia sects did not limit it to descendants of Ali and Muhammad, but to the extended family of Muhammad in general. One such group, alongside Sunnis,[54] supported the rebellion against the Umayyads led by the Abbasids, who were descendants of Muhammad's paternal uncle Abbas. However, when the Abbasids came to power in 750, they began championing Sunni Islam, alienating the Shi'ites. Afterwards, the sect limited the succession to descendants of Ali and Fatimah in the form of Imams.[41]

Twelver Shia view

| Part of a series on Islam Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs and practices |

|

|

Holy women |

|

|

With the exception of Zaydis,[55] Shi'ites believe in the Imamate, a principle by which rulers are Imams who are divinely chosen, infallible and sinless and must come from the Ahl al-Bayt regardless of majority opinion, shura or election.[56] They claim that before his death, Muhammad had given many indications, in the Event of Ghadir Khumm in particular, that he considered Ali, his cousin and son-in-law, as his successor.[57] For the Twelvers, Ali and his eleven descendants, the twelve Imams, are believed to have been considered, even before their birth, as the only valid Islamic rulers appointed and decreed by God.[58][59] Shia Muslims believe that with the exception of Ali and Hasan, all the caliphs following Muhammad's death were illegitimate and that Muslims had no obligation to follow them.[60] They hold that the only guidance that was left behind, as stated in the hadith of the two weighty things, was the Quran and Muhammad's family and offspring.[61] The latter, due to their infallibility, are considered to be able to lead the Muslim community with justice and equity.[62]

Zaydi Shia view

Zaydis, a Shia sub-group, believe that the leaders of the Muslim community must be Fatimids: descendants of Fatimah and Ali, through either of their sons, Hasan or Husayn. Unlike the Twelver and Isma'ili Shia, Zaydis do not believe in the infallibility of Imams nor that the Imamate must pass from father to son.[63] They named themselves Zaydis after Zayd ibn Ali, a grandson of Husayn, who they view as the rightful successor to the Imamate. This is due to him having led a rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate, who he saw as tyrannical and corrupt. The then Twelver Imam, his brother Muhammad al-Baqir, did not engage in political action and the followers of Zayd believed that a true Imam must fight against corrupt rulers.[64]

One faction, the Batriyya, attempted to create a compromise between the Sunni and Shia by admitting the legitimacy of the Sunni caliphs while maintaining that they were inferior to Ali. Their argument was that while Ali was the best suited to succeed Muhammad, the reigns of Abu Bakr and Umar must be acknowledged because Ali had recognised them.[63] This belief, termed Imamat al-Mafdul (Imamate of the inferior), is one which has also been attributed to Zayd himself.[65][note 4]

Sunni view

| |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Lists |

|

|

The general Sunni belief states that Muhammad had not chosen anyone to succeed him, instead reasoning that he had intended for the community to decide on a leader amongst themselves. However, some specific hadiths are used to justify that Muhammad intended Abu Bakr to succeed, but that he had shown this decision through his actions rather than doing so verbally.[18]

The election of a caliph is ideally a democratic choice made by the Muslim community.[66] They are supposed to be members of the Quraysh, the tribe of Muhammad. However, this is not a strict requirement, given that the Ottoman Caliphs had no familial relation to the tribe.[67] They are not viewed as infallible and can be removed from office if their actions are regarded as sinful.[66] Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali are regarded as the most righteous of their generation, with their merit being reflected in their Caliphate. The subsequent caliphates of the Umayyads and the Abbasids, while not ideal, are seen as legitimate because they complied with the requirements of the law, kept the borders safe and the community generally united.[68]

Ibadi view

The Ibadi, an Islamic school distinct from the Sunni and Shia,[69] believe that leadership of the Muslim community is not something which should be decided by lineage, tribal affiliations or divine selection, but rather through election by leading Muslims. They see the leaders as not being infallible and that if they fail to maintain a legitimate government in accordance to Islamic law, it is the duty of the population to remove them from power. The Rashidun Caliphs are seen as rulers who were elected in a legitimate fashion and that Abu Bakr and Umar in particular were righteous leaders. However, Uthman is viewed as having committed grave sins during the latter half of his rule and was deserving of death. Ali is also similarly understood to have lost his mandate.[70]

Their first Imam was Abd Allah ibn Wahb al-Rasibi, who was selected after the group's alienation from Ali.[71] Other individuals seen as Imams include Abu Ubaidah Muslim, Abdallah ibn Yahya al-Kindi and Umar ibn Abdul Aziz.[72]

See also

- Hadith of the two weighty things

- Hadith of the pen and paper

- Hadith of the Twelve Successors

- Saqifa

- The event of Ghadir Khumm

Notes

- A consideration of oral transmissions in general with some specific early Islamic reference is given in Jan Vansina's Oral Tradition as History.

- It is not known which Ja'far is being referred to, though he cannot be identified with Ja'far ibn Abi Talib, who had been killed in battle in 629.[26]

- Ali's paternal great-grandmother, Salma bint Amr, had been a member of the Banu Khazraj.[42]

- Al-Tabari records that when asked about Abu Bakr and Umar, Zayd stated "I have not heard anyone in my family renouncing them both nor saying anything but good about them...when they were entrusted with government they behaved justly with the people and acted according to the Quran and the sunnah."[65]

References

- Reeves, Minou (2003). Muhammad in Europe: A Thousand Years of Western Myth-Making. NYU Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-8147-7564-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Chase F. (2003). Islamic Historiography. Cambridge University Press. p. xv. ISBN 0-521-62936-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donner, Fred McGraw (1998). Narratives of Islamic origins: the beginnings of Islamic historical writing. Darwin Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-87850-127-4. Retrieved 3 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nigosian, Solomon Alexander (1 January 2004), Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices, Indiana University Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4, retrieved 3 January 2013CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watt, William Montgomery (1953). Muhammad at Mecca. Clarendon Press. p. xv. Retrieved 3 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cragg, Albert Kenneth. "Hadith". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-04-16. Retrieved 2008-03-30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press. p. xi. ISBN 0-521-64696-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caetani, Leone (1907). Annali dell'Islam. II, Part I. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli. pp. 691–92.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madelung 1997, p. 20

- See:

- Sachedina, Abdulaziz Abdulhussein (1981). Islamic messianism : the idea of Mahdī in twelver Shīʻis. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-87395-458-0.

- Landolt, Hermann; Lawson, Todd (2005). Reason and inspiration in Islam : theology, philosophy and mysticism in Muslim thought : essays in honour of Hermann Landolt. London ; New York: I.B. Tauris. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-85043-470-2.

- Modarressi, Hossein (2003). Tradition and survival: a bibliographical survey of early Shī'ite literature. Oneworld. pp. 82–88. ISBN 978-1-85168-331-4. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Dakake, Maria Massi (2007). The Charismatic Community: Shiʻite Identity in Early Islam. State University of New York Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7914-7033-6. Retrieved 3 January 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khetia, Vinay (2013). Fatima as a Motif of Contention and Suffering in Islamic Sources. Concordia University. p. 60.

- Zwettler, Michael (1990). "A Mantic Manifesto: The Sura of "The Poets" and the Qur'anic Foundations of Prophetic Authority". Poetry and Prophecy: The Beginnings of a Literary Tradition. Cornell University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-8014-9568-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rubin, Uri (1995). The Eye of the Beholder: The life of Muhammad as viewed by the early Muslims. Princeton, New Jersey: The Darwin Press Inc. pp. 135–38. ISBN 9780878501106.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Razwy, Sayed Ali Asgher. A Restatement of the History of Islam & Muslims. pp. 54–55.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rubin (1995, p. 137)

- Irving, Washington (1868), Mahomet and His Successors, I, New York: G. P. Putnam and Son, p. 71

- Rubin (1995, pp. 136–37)

- Sodiq, Yushau (2010), An Insider's Guide to Islam, Trafford Publishing, p. 64, ISBN 978-1-4269-2560-3

- A's Suyuti, Jalaluddin (1881). History of the Caliphs. Translated by H.S. Jarrett. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press. p. 6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miskinzoda, Gurdofarid (2015). "The significance of the ḥadīth of the position of Aaron for the formulation of the Shīʿī doctrine of authority". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 78 (1): 68–69. doi:10.1017/S0041977X14001402.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miskinzoda (2015, p. 67)

- Miskinzoda (2015, p. 72)

- "And Moses said to his brother Aaron, "Take my place among my people, do right [by them], and do not follow the way of the corrupters.""[Quran 7:142]

- Miskinzoda (2015, pp. 79–80)

- Miskinzoda (2015, pp. 75–76)

- Miskinzoda (2015, p. 69)

- Miskinzoda (2015, p. 82)

- [Quran 7:148–152]

- "[Aaron] said, "O son of my mother, do not seize [me] by my beard or by my head. Indeed, I feared that you would say, 'You caused division among the Children of Israel, and you did not observe [or await] my word.' ""[Quran 20:94]

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali (2014). Kate Fleet; Gundrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). ""Ghadīr Khumm" in: Encyclopaedia of Islam THREE". doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_27419. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "The Event of Ghadir Khumm in the Qur'an, Hadith, History". islamawareness.net. Archived from the original on 2006-01-07. Retrieved 2005-09-02.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaban, M. A. (1971), Islamic History: A New Interpretation, I, Cambridge University Press, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-521-29131-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wain, Alexander; Kamali, Mohammad Hashim (2017). The Architects of Islamic Civilisation. Pelanduk Publications. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-967-978-989-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzpatrick, Coeli; Walker, Adam Hani (2014). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-61069-178-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayaat al-Qulub, Volume 2. p. 998.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:70:573

- Miskinzoda, Gurdofarid (2014). Farhad Daftary (ed.). The Story of Pen & Paper and its interpretation in Muslim Literary and Historical Tradition. The Study of Shi‘i Islam: History, Theology and Law. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-529-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzpatrick & Walker (2014, p. 3)

- Madelung 1997, p. 31

- Madelung (1997, p. 32)

- Hoffman, Valerie J. (2012). The Essentials of Ibadi Islam. Syracuse University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8156-5084-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madelung (1997, p. 36)

- Madelung (1997, pp. 32–33)

- Fitzpatrick & Walker (2014, p. 186)

- Fitzpatrick & Walker (2014, p. 4)

- Jafri, S.H.M. (1979). The Origins and Early Development of Shia Islam. London: Longman. p. 23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Badie, Dina (2017). After Saddam: American Foreign Policy and the Destruction of Secularism in the Middle East. Lexington Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4985-3900-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Searcy, Kim (2011). The Formation of the Sudanese Mahdist State: Ceremony and Symbols of Authority: 1882-1898. BRILL. p. 46. ISBN 978-90-04-18599-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Corrigan, John; Denny, Frederick; Jaffee, Martin S.; Eire, Carlos (2016). Jews, Christians, Muslims: A Comparative Introduction to Monotheistic Religions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34699-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Badie (2017, p. 4)

- Cooperson, Michael (2000). Classical Arabic Biography: The Heirs of the Prophets in the Age of al-Ma'mun. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-139-42669-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glassé, Cyril; Smith, Huston (2000). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-7591-0190-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Middleton, John (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-317-45158-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Badie (2017, p. 6)

- Robinson, Francis (1984). Atlas of the Islamic World Since 1500. New York: Facts on File. p. 47. ISBN 0871966298.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheriff, Ahmed H. (1991). Leadership by Divine Appointment. p. 13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rizvi, Kishwar (2017). Affect, Emotion, and Subjectivity in Early Modern Muslim Empires. BRILL. p. 101. ISBN 978-90-04-35284-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malbouisson, Cofie D. (2007). Focus on Islamic Issues. Nova Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-60021-204-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stefon, Matt (2009). Islamic Beliefs and Practices. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-61530-017-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madelung, Wilferd (1985). Religious Schools and Sects in Medieval Islam. Variorum Reprints. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-86078-161-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Galian, Laurence (2003). The Sun at Midnight: The Revealed Mysteries of the Ahlul Bayt Sufis. p. 230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mishal, Shaul; Goldberg, Ori (2014). Understanding Shiite Leadership: The Art of the Middle Ground in Iran and Lebanon. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-107-04638-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkins, Everett (2010). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 1, 570-1500): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. 1. McFarland. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7864-4713-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ali, Abdul (1996). Islamic Dynasties of the Arab East: State and Civilization during the Later Medieval Times. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 97. ISBN 978-81-7533-008-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (1989). The History of al-Tabari, Volume XXVI: The Waning of the Umayyad Caliphate. Translated by Carole Hillenbrand. State University of New York Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-88706-810-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khadduri, Majid; Liebesny, Herbert J. (2008). Origin and Development of Islamic Law. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-58477-864-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hay, Jeff (2007). The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of World Religions. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7377-4627-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Mirza, Mahan; Kadi, Wadad; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim; Stewart, Devin J. (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-691-13484-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoffman (2012, p. 3)

- Hoffman (2012, pp. 7–9)

- Hoffman (2012, p. 10)

- Hoffman (2012, pp. 12–13)

Further reading

Academic books

- Ashraf, Shahid (2004), Holy Prophet and Companions (15 Vol Set), Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 978-81-261-1940-0, retrieved 3 January 2013

- Chirri, Mohamad Jawad (1982), The brother of the prophet Mohammad (the Imam Ali): a reconstruction of Islamic history and an extensive research of the Shi-ite Islamic school of thought, Islamic Center of Detroit, retrieved 3 January 2013

- Holt, P. M.; Lewis, Bernard (1977), Cambridge History of Islam, I, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29136-4

- Lapidus, Ira (2002), A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn; Nasr, Hossein (translator) (1979), Shi'ite Islam, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-87395-272-3

Shia books

- Shi'a Islam (book), by Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei and Hossein Nasr, State University of New York Press, 1979

- Al-Murāja'āt: A Shī'i-Sunni Dialogue by Sayyid 'Abdul-Husayn Sharafud-Dīn al-Mūsawi, 2001, Ansariyan Publications: Qum, Iran.

- Peshawar Nights by Sultanu'l-Wa'izin Shirazi, 2001, Ansariyan Publications: Qum, Iran.

- Ask Those Who Know by Muhammad al-Tijani, 2001, Ansariyan Publications: Qum, Iran.

- To be with the Truthful by Muhammad al-Tijani, 2000, Ansariyan Publications: Qum, Iran.

- The Shi'a: The Real Followers of the Sunnah by Muhammad al-Tijani, 2000, Ansariyan Publications: Qum, Iran.

- Imamate and Leadership by Mujtaba Musavi Lari

- the Vicegerency of the Prophet by Rizvi, S. Saeed Akhtar, (Tehran: WOFIS, 1985) pp. 57–60.

- Fara'id al-Simtayn by the Shia scholar Ibrahim b Muhammad b Himaway al Juwayni who died in 1322 AD/ 722 AH. (The Scale of Wisdom by M. Muhammadi Rayshahri)(Al-Tawhid Vol 8, Sāzmān-i Tablīghāt-i Islāmī (Tehran, Iran), p170)

Sunni books

- Sealed Nectar by Saifur Rahman al-Mubarakpuri, 2002, Darussalam Publications.

- Al-Bukhari Translated by Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan, 1997, Darussalam Publications

- Peshawar Nights the Art of Fictional-Narration by Abu Muhammad al-Afriqi

- Life of Muhammad by Muhammad Husayn Haykal

- Prophet Muhammad and The First Muslim State by Mohammad Mahmoud Ghali

- Abu Bakr As-Siddeeq by Muhammad Rajih Jad'an

- The Biography of Abu Bakr As Siddeeq by Ali al-Sallabi