Underwater searches

Underwater searches are procedures to find a known or suspected target object or objects in a specified search area under water. They may be carried out underwater by divers, manned submersibles, remotely operated underwater vehicles, or autonomous underwater vehicles, or from the surface by other agents, including surface vessels, aircraft and cadaver dogs.

A search method attempts to provide full coverage of the search area. This is greatly influenced by the width of the sweep which largely depends on the method used to detect the target. For divers in conditions of zero visibility this is as far as the diver can feel with his hands while proceeding along the pattern. When visibility is better, it depends on the distance at which the target can be seen from the pattern, or detected by sonar or magnetic field anomalies. In all cases the search pattern should completely cover the search area without excessive redundancy or missed areas. Overlap is needed to compensate for inaccuracy and sensor error, and may be necessary to avoid gaps in some patterns.

Diver searches

Diver searches are underwater searches carried out by divers. There are a number of techniques in general use by Commercial, Scientific, Public service, Military, and Recreational divers. Some of these are suitable for Scuba, and some for surface supplied diving. The choice of search technique will depend on logistical factors, terrain, protocol and diver skills.

As a general principle, a search method attempts to provide 100% coverage of the search area. this is greatly influenced by the width of the sweep. In conditions of zero visibility this is as far as the diver can feel with his hands while proceeding along the pattern. When visibility is better, it depends on the distance at which the target can be seen from the pattern. In all cases then, the pattern should be accurate and completely cover the search area without excessive redundancy or missed areas. Overlap is needed to compensate for inaccuracy, and may be necessary to avoid gaps in some patterns.

Search patterns controlled by ropes and lines

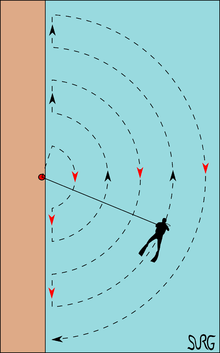

Circular search

An underwater circular search is a procedure conducted by a diver swimming at a series of distances (radii) around a fixed reference point. The circular search is simple and requires little equipment. It is useful where the position of the objects of the search is known with reasonable accuracy.[1]:142

Procedure

The general procedure is to start from a fixed central point, and to search the circumference of a circle where the radius is defined by a search line anchored at the central point. The radius of the circle is dependent on visibility, and is increased after each circle has been completed, by an amount which allows the diver to either see or feel an overlap between the current arc and the previous arc.[2][3]

One end of the distance line is carried by the diver and the other is attached to the datum position by any appropriate method. E.g. clipped to the base of a shot line, pegged into the bottom, tied to a fixed object on the bottom or held by another diver. The diver may tow a surface marker buoy if conditions allow. The diver unreels a section of distance line appropriate to the visibility and mark his start position by a peg, loose marker, compass heading, or a pre-laid marker line extending outwards from the datum position. Then, keeping the line taut, the diver swims in a circle with the line as radius, searching visually or by feel until back at the start position. He then unreels another section of line of the same length and repeats the procedure until he finds the object, runs into obstacles or runs out of line, air or time.[1]:142

The amount of distance line increment for each sweep should allow some overlap of sweeps to avoid the risk of missing the target between sweeps. If a buddy is involved the most efficient place is alongside the controlling diver on the line, and the extension of distance line for each sweep can be roughly doubled. Depending on the circumstances, control of the pattern may be from the surface, from a diver at the central point, or by the diver at the end of the search line, who would in that case control the search line reel.[1]:142

Variations on the circular search

In some cases a second diver can anchor himself to the bottom and act as both the central point and line tender. The diver and line tender communicate with each other using line pull signals. When the diver has completed a full revolution of the search, the tender signals the diver and advances another section of line so the search can be expanded further from the central point. Another variation uses more than one diver along the search line. The divers are evenly spaced at a distance depending on visibility, and the increase in radius allows overlap of search area only for the innermost diver on the line. This variation becomes more difficult to coordinate with a larger number of divers, particularly in poor visibility.[1]:142

A major variation on the circular search is the pendulum search, also known as the arc or fishtail search.[2][3] in which the diver stops and changes direction at the end of each arc. This is used when there is insufficient space to complete a circle, as when controlled from the shore, or when the search area is limited to a sector to one side of the control point, or there is a major obstruction limiting the extent of the searchable sector. Divers on surface supply may change direction at the end of each arc even when using a full 360° pattern to avoid twisting the umbilical. The pendulum search can also be done with more than one diver on the search line, but this requires considerable skill and co-ordination, particularly in low visibility.[4]

Another variation is used where the target is large enough to snag the search line, In this case the diver may go out to the full radius of the search area and make a single sweep, hoping to snag the target with the line. If on his return to the start line or bearing, he finds he is closer to the centre point, he will swim back along the line in the expectation of having snagged something. With some luck it will be the target of the search.

If the target is not found by the time the search pattern has reached maximum convenient radius, the centre point may be shifted and another search started. This can be repeated as often as necessary, but the positions of the centre points must be chosen to allow the full search area to be covered. This implies quite a lot of overlap, and the pattern is not efficient. The most efficient pattern uses an equilateral triangular grid, but this may have to be modified to suit the site.[4]

The circular search is very popular as it does not require complicated setup and can be done by most divers without a great deal of special training. It is effective where the position of the target is known with reasonable accuracy, where the bottom terrain does not have major snags, and where the depth variation during each arc is acceptable.[4]

Safety

Divers should be well trained in general diving skills before attempting this type of search. The search diver is responsible for maintaining sufficient tension on the search line so the signals can be transmitted and received. If a surface marker is used, slack in the line should be kept to a minimum to avoid entanglement. This is easiest if a reel is used to control the line, or alternatively the line should be buoyant, to keep it as far from the divers as possible, but buoyant lines will still tend to wrap around the shotline in the centre if there is enough slack.[4]

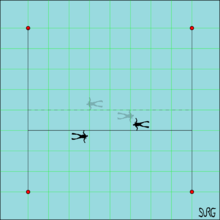

Jackstay search

An underwater jackstay search is a procedure conducted by divers swimming along a search line - the jackstay.

There are various techniques for performing a jackstay search.

Procedure

The procedure for a search using two fixed jackstays and a movable search line is described:[3]

The distance between the fixed jackstays will depend on circumstances, but should not be so long that reliable overlapping of sweeps is prevented. This will depend on the bottom terrain. Two divers are generally used on this search system. Two heavy jackstays are laid parallel to each other across the bottom of the search area. A lighter movable jackstay is used to connect the fixed jackstays at one end of the search area. This line is kept reasonably taut, but must not pull the fixed jackstays together.[4]

The divers start at opposite ends of the movable jackstay and swim along it, each diver holding the line with his left hand (or right, but both must use the same hand to keep them on opposite sides of the line) and searching the bottom visually or by feel on his side of the line until he passes the other diver and reaches the other fixed jackstay, at which point he will signal to the other diver that he has reached this point by a pull signal on the movable jackstay.[1]:141

When both divers are at the fixed jackstays they will shift the movable jackstay along the fixed jackstays by an agreed distance depending on conditions. The distance should be large enough to reduce excessive overlap, but small enough that there is no risk of missing the target between traverses. This usually means that the distance is between the reach of the divers searching by feel in low visibility, and the distance they can see to the sides plus width of the target in good visibility. Care must be taken to always shift the movable jackstay in the same direction. This can be easily confused in low visibility, so a compass can be used to prevent this problem.[4]

The divers then repeat this process until they find the object or run out of fixed jackstay, time or air. When a diver finds the object he should signal this to the other diver by rope pulls. The second diver can join him to confirm the finding and mark it or continue the search. If the movable jackstay snags it should be freed by the divers as the pass the snag. The sweep may have to be repeated after freeing a snag. The method of attaching the movable jackstay should be easily adjustable, but reliable.[4]

If a series of sweeps does not find the object, one of the fixed jackstays may be lifted and re-laid on the opposite side of the remaining one, and the process repeated until the target is found or the entire search area has been searched.[4]

Variations on the jackstay search

If the body of water is narrow enough, a surface team can lay a single jackstay across the width of the bottom, and the diver/s swim from one side to the other. When they reach the end of the line in the water, the surface team advance the jackstay by an appropriate amount by lifting it, moving it parallel to the original position and laying it down again, at which stage the divers make another sweep. This is repeated as often as necessary.

Another method, sometimes called a "J" search, and suitable for a solo diver, involves the diver or divers starting at the same end of the search line, which is similarly set along the edge of the search area. The two divers swim together, one on each side of the line, thereby searching the area immediately to either side of the line.

Once they have completed the sweep, they reset the end of the line a few meters further into the search area, so that the line now runs at a slight angle to its original course. They then sweep back along the line, either searching much of the same ground over again, or simply returning to the start point. Once they reach the start point, they then move the other end of the line a few meters further into the search area so that the line is once again parallel to its original position.

They repeat this pattern until the object of the search is located, or until they cover the entire search area. This second method is longer and slower, and is used more frequently either in extremely limited visibility, where the divers do not wish to lose contact with each other, or where the object sought is particularly small, and they wish to run the pattern twice, once from each side, in case the object is masked by a larger object on the sea bed when approach from one side, and particularly where only one diver is available to do the search.

Safety

It is important to note that divers should be well trained before attempting this type of search. Solo divers should be used only when a risk assessment indicates that the risks are acceptable, and preferably should indicate their position with a surface marker or be in communication with the surface by line or voice.

Snag-line search

When the object of the search is large enough and of suitable form to snag a dragged line, a snag-line may be used to speed up the process. The snag-line may be used with a pair of fixed jackstays or as a distance line for a circular search. It is often a weighted line, though there may be times when this is not required. The snag-line is held taut by the diver or divers, who will then drag it along the bottom as they either follow the jackstays or swim the arc until it hooks on something. When this happens the divers fasten their snag-line ends in position by tying them to the jackstays or pegging to the ground and swim along the snag-line to identify the target, If it is the object of the search, they will mark it, otherwise they free the line, move it over the target, return to their ends and continue the sweep.[3][4]

Search patterns controlled by compass directions

Spiral box search

An underwater spiral box search is a search procedure conducted by a diver swimming around a starting point on a pattern based on compass directions and increasing distances. The pattern resembles an outward spiral with straight sides and equal distances between legs swum on the same bearing. The legs are normally swum with 90 degree change in direction between them, and very often the cardinal directions are used for ease of navigation. The spiral may be clockwise or anticlockwise, and in theory there is no limit to the area which can be covered. In practice, the diver may encounter an obstacle such as the shore, or will run out of air or energy, which will terminate the pattern. Finding a specified target would also result in the termination of the search in most cases.[1]:143

Procedure

The technique is to start at the estimated position of the target, at a distance above the bottom to provide the best view, and to swim in a cardinal direction a distance roughly equal to or slightly greater than the visibility range. The estimate of distance is commonly by kick counts, so using a whole number of kicks is necessary, and preferably a number which can be mentally accumulated by the diver. Call this distance n kicks, where n is usually 2, 4, 5, 10 or 20 as these are easy numbers to multiply mentally. The direction of turn may be clockwise or anticlockwise as best suits the search.

For example: The diver swims n kicks to the north, turns left and swims n kicks to the west, then turns left and swims 2n kicks to the south, left again and 2n kicks to the east. Then left again and 3n kicks to the north, left and 3n kicks to the west. The pattern is repeated by adding an extra n kicks every second turn, and always turning the same way. If at any stage the diver wants to return to the start point, he will swim a half leg count followed by the usual turn and another half leg count.

Applications

This search pattern is particularly suited for occasions when the approximate position of the search target is known, but the divers have no facilities for setting up a position marker or search lines, but have a compass and the skills to use it effectively. The pattern is not greatly affected by obstructions and potential snags, bur works best with targets that are relatively easy to see, and that usually implies fairly large size and fairly good visibility. The gap between the parallel legs is chosen for easy counting and sufficient overlap to provide a good chance of spotting the target.

The pattern is not suited to water where there is a current, though moderate surge does not make much difference to the accuracy, provided the horizontal movement due to the surge is not bigger than the overlap between two adjacent parallel legs. Errors are cumulative: A return to the centre is a good check for accuracy. If the diver ends up close to the start point, the pattern was swum accurately.

Compass grid search

An underwater compass grid search is a search pattern conducted by a diver swimming parallel lines on a compass bearing and its reciprocal while conducting a visual search of the area bordering the track. The separation between lines is chosen to allow sufficient overlap to ensure a high probability of the search target being seen if the diver passes by. Cardinal directions are often chosen for ease of navigation, but topographical constraints may dictate bearings that suit the site better.

Procedure

The diver or divers swim pre-arranged compass courses arranged in a grid pattern to cover the search area.

Applications

A large number of divers can be simultaneously deployed to cover a large search area quickly, or a single diver can methodically work through the same area. The pattern is limited to relatively low current speeds, as the current will set the divers off their planned paths.

Ladder search

This pattern is a version of the grid search where the length of the leg is relatively short. It is more limited, but works well in narrow passages, like a river or canal. The search pattern is swimming back and forth on reciprocal headings with an equal offset in the same direction at the end of each leg. Direction of the legs is usually determined by some geographical feature, and the bezel of the compass can be set to those directions. If the direction of the channel changes it may be necessary to change the search leg headings accordingly, so that they remain roughly transverse to the channel. The offset is not critical for direction, and so long as it is roughly correct will be OK. The length of the search legs will usually also be determined by some physical feature like the width of the canal, or reaching a depth of 10m, and the legs may not be of constant length. What is important is that they are parallel and each is offset the same amount in the same direction, so that the search area is covered completely. The search pattern corresponds closely to that of the Jackstay grid search.

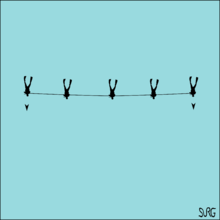

Swim-line search

This is the visual equivalent of the snag-line search. A team of divers spreads out along a length of rope at spacing suited to the visibility, terrain and size of the target. The team leader may theoretically be anywhere on the rope, but is usually at one end or in the middle. He swims on a constant heading which is known to all the divers, who swim on the same heading. Each diver must ensure that he does not get ahead of or lag behind the diver to his side who is closer to the leader, and that the rope is kept taut. In this way an evenly spaced line of divers swims a straight sweep with a width equal to the length of the swim line. It can work but requires concentration and a bit of practice, as all the divers are also supposed to be diligently searching for the target. The swim line method can also be applied to a circular pattern, but this is inefficient and usually badly co-ordinated as the direction is constantly changing. A variation on this pattern that can work is in a river or canal where the ends are controlled by line tenders on the banks, who can communicate and can sweep the line round curves. Complications arise with variations in width but most of these can be dealt with by planning ahead. Line signals can instruct the divers to adjust their spacing to suit conditions.[3][4]

Searches directed from the surface

Directed search using line signals or voice communications

A diver who is in communication with the surface by line signals or by voice communication may be directed to and around a search area from the surface. This has a relatively limited scope, but can work in some cases, particularly when the surface team has a real time sonar picture of the target and the diver in bad visibility. This may be considered not to be a search, as the target can be seen, and the position known, but it is not always possible to get a positive identification until the diver gets there, and there may be several potential targets to check. The technique is also sometimes used when the approximate position can be judged from the surface, but the diver still needs to do some searching once in the desired position.[4]

Towed searches

One or two divers can be towed behind a boat at speeds up to 3.5 or 4 km per hour to do visual searches. They steer and control their depth by using a tow board, which may be equipped with a safety quick disconnect mechanism and drop-floats to mark targets.[5]

Suitable for searching large area in good visibility for a large target. The diver must be careful not to ascend too quickly. When a target is seen the diver will disconnect the board and send up a marker buoy, which will indicate the position of the target and the diver, allowing the boat to approach with caution while the diver ascends. The search pattern is controlled by the skipper of the boat, and may follow a GPS defined route. If the visibility is good enough or the water shallow, the divers can search while towed at the surface.[6]

Searches using special equipment

Searches using hand held submersible sonar transponders

Active (transponders that emit a signal and measure the return signal strength to determine obstructions in a given direction) or passive (transponders which measure a signal emitted by the target) sonar can be used by divers on underwater searches.

A signal transmitter attached to the target instrumentation package is often used to allow scientists to recover instrumentation relatively quickly, where the position can not be marked at the surface by a buoy. The diver carries a receiver which is tuned to the frequency of the transmitter, and is usually capable of indicating signal strength and the direction it comes from, allowing the diver to proceed towards it on a fairly direct route. The transmitter may be triggered by a coded sonar signal from the surface or a timer.

Inertial navigation instruments which can be used to give a precise position to the diver can be used to follow a planned search pattern in much the same way that a compass is used, but are better in currents, as they give an absolute position and directions.

Other search patterns

Current drift search

Divers are spaced out across the direction of current flow and search as they are carried over the bottom by the current. They would usually be monitored from the surface using marker buoys so that the effectiveness of coverage can be assessed, and the search is likely to be most effective in good visibility and in areas where the current velocity is reasonably consistent. This is very similar in effect to the swimline visual search, and the techniques can be combined.

Depth contour search

Steeply sloping bottoms can sometimes be effectively searched by divers swimming at constant depth, following the contours of the bottom. Depth control may be by gauge, but is very effectively managed by towing a surface marker buoy with the line length set to the desired depth, provided that the surface is not too rough.

Communication

Most public safety divers and many recreational divers communicate by line signals while conducting searches underwater.

By submersibles, remotely operated vehicles and autonomous underwater vehicles

Manned submersibles, ROVs and AUVs can search underwater using visual, sonar and magnetometer detection equipment.

For example, the US Navy's Advanced Unmanned Search System is capable of deep ocean, large area side-scan sonar search and detailed optical inspection, after which it can resume the search where it left off. It use doppler sonar and a gyrocompass to navigate, and can operate to 6,000 metres (20,000 ft) depth.[7]

By surface vessels

Surface vessels can search underwater using sonar and magnetometer detection equipment.[8][9] Sometimes a visual search is also possible.

Side-scan sonar imagery can be useful to identify objects which stand out from the surrounding topography. It is particularly useful in deep water and on smooth bottoms where the target is easily distinguished. It is less effective in areas where the target may be heavily encrusted with marine growth or otherwise hidden in the complexities of the bottom topography.[10] Sonar produces a picture of the bottom by plotting the image derived from the time between emission of a sound signal from the transducer and the reception of an echo from a given direction. Resolution decreases with distance from the transducer, but at moderate range the form of a human body can be recognisable, making this a useful method for search and recovery operations. A transducer (known as the "fish") can be towed behind a vessel at a desired depth to provide suitable resolution. The image is recorded and the position of the fish relative to the vessel correlated with positional input from the vessel, usually from GPS. A search pattern which covers the whole search area with consistent relative position between transducer and tow vessel is most effective. Once a target has been found it is usually investigated further by diver or ROV for positive identification and whatever other action is appropriate.

A magnetometer basically measures the magnetic field of the surroundings, and can detect very small local variations which may indicate the presence of magnetic materials. when a magnetometer is towed behind a vessel at a distance where the magnetic field of the towing vehicle does not overwhelm the signal, it can be a sensitive indicator of variations due to geological deposits or artifacts. The signal is correlated to position input, usually from GPS, to indicate local magnetic anomalies which may be worth further investigation by diver or ROV. Towed magnetometer searches are useful for finding artifacts such as shipwrecks and aircraft wrecks.[10]

By aircraft

Manned aircraft and drones can be used for visual searches in good visibility and shallow water, and for magnetometer searches.

Active and passive sonobuoys may be used to search for and locate the position of a submerged submarine. They may be anchored in shallow water, or free-floating in deep water. and may be part of a long term early-warning system, or actively used to hunt down enemy vessels The position of the target is identified by analysing the time difference of the same sound signals either emitted or reflected from the target and received by three or more buoys. The buoys may be deployed by conventional aircraft or helicopter, or by ships.[11]

Air searches can be done for magnetic targets using magnetic anomaly detection (MAD) systems, which use a sensitive magnetometer carried by an aircraft. These can be done for static targets following search patterns similar to those used by surface craft, or for moving targets such as submarines by search patterns optimised to improve the probability of identifying the position of a moving target. MAD detection of submarines is used to track down the current position of a submarine known to be in the area for purposes of identification, confirmation of suspected presence, tracking of movements and launching of weaponry.[12]

From the shore

Draglines have been used from the shore to locate suitable targets. Lines with hooks or grapnels may be thrown or carried out from the shore and then pulled in in the hope of snagging the target, Once snagged, the procedure depends on whether the target is likely to be pulled out, or must be inspected in situ.

Cadaver dogs are used by law enforcement and public safety agencies to detect missing bodies underwater. This is most effective in shallow and confined water without much current. The dogs can also be transported over the water in boats to expand the search area or attempt to provide more precise location. [13] The dogs are most effective when they can get right down to the water surface to smell and taste it, which requires a boat with low freeboard.[14] Dog searches for underwater cadavers is complicated by the movement of water and wind, which move the smell away from the source.[15]

References

- Busuttili, Mike; Holbrook, Mike; Ridley, Gordon; Todd, Mike, eds. (1985). "Using basic equipment". Sport diving – The British Sub-Aqua Club Diving Manual. London: Stanley Paul & Co Ltd. p. 58. ISBN 0-09-163831-3.

- NOAA Diving Program (U.S.) (28 Feb 2001). Joiner, James T. (ed.). NOAA Diving Manual, Diving for Science and Technology (4th ed.). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, National Undersea Research Program. ISBN 978-0-941332-70-5. CD-ROM prepared and distributed by the National Technical Information Service (NTIS)in partnership with NOAA and Best Publishing Company

- Larn, Richard; Whistler, Rex (1993). Commercial Diving Manual (3rd ed.). Newton Abbott, UK: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-0100-4.

- Hanekom, Paul; Truter, Pieter (February 2007). "Section 17: Seabed searches". Diver Training Handbook (3rd ed.). Cape Town, South Africa: Research Diving Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Dowsett, Kathy (15 November 2016). "Safety, precision searching keys in underwater diver towing". The Scuba News Canada: Equipment News. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- "Search Patterns: Planing board search". Ventura County Sheriff's Search and Rescue Dive Team. Ventura County Sheriff's Department. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- Committee on Undersea Vehicles and National Needs, Marine Board, Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems, National Research Council (1996). "Chapter 2: Undersea Vehicle Capabilities and Technologies - Autonomous Underwater Vehicles". Undersea Vehicles and National Needs (Report). Washington, D.C.: National academies press. p. 22.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Staff (September 2000). Instructor notes: Search and Recovery. Ellesmere Port, Cheshire: British Sub-Aqua Club.

- Sakellariou, Dimitris; Georgiou, Panos; Mallios, Aggellos; Kapsimalis, Vasilios; Kourkoumelis, Dimitris; Micha, Paraskevi; Theodoulou, Theotokis; Dellaporta, Katerina (2007). "Searching for Ancient Shipwrecks in the Aegean Sea: the Discovery of Chios and Kythnos Hellenistic Wrecks with the Use of Marine Geological-Geophysical Methods" (PDF). The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Oxford, UK. 36 (2): 365–381. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2006.00133.x. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Ho, Bert (17 April 2017). "Searching for Airplanes with a Magnetometer". Ocean Explorer: Exploring the Sunken Heritage of Midway Atoll. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Wahlstedt, Alexander; Fredriksson, Jesper; Jöred, Karsten; Svensson, Per (April 1997). Submarine Tracking by Means of Passive Sonobuoys (PDF). FOA-R--96-00386-505--SE (Report). Linköping Sweden: Defence Research Establishment, Division of Command and Control Warfare Technology. ISSN 1104-9154.

- Kuwahara, Ronald H. (2012). "Computer simulation of search tactics for magnetic anomaly detection". In Haley, K. (ed.). Search Theory and Applications. Nato Conference Series II: Systems Science. 8 (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781461591887.

- Lyst, Catherine (15 December 2014). "The dog that finds underwater bodies". BBC Scotland news website. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- University of Huddersfield staff (16 September 2015). "Cadaver Dogs Locate Underwater Corpses". www.forensicmag.com. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- Staff (10 September 2015). "Research shows value of cadaver dogs locating underwater corpses". University of Huddersfield News. Retrieved 11 September 2017.