Taiwanese nationality law

The Nationality Act of the Republic of China defines and regulates the acquisition, loss, restoration, and revocation of the nationality of the Republic of China, commonly known as Taiwan. Nationality is in the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior and is based on jus sanguinis.[1]

| Nationality Act 國籍法 Guójí Fǎ (Mandarin) Kok-che̍k Hoat (Taiwanese) Koet-sit Fap (Hakka) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Legislative Yuan | |

| Territorial extent | Free area of the Republic of China (includes Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, and outlying islands) |

| Enacted | February 5, 1929 |

| Effective | February 5, 1929 |

| Administered by | Ministry of the Interior |

| Amended by | |

| February 9, 2000 (amending the whole law) December 21, 2016 (last amended) | |

| Status: Amended | |

History

According to the Treaty of Shimonoseki, the inhabitants of Taiwan (including Penghu) were granted the nationality of the Empire of Japan and lost the nationality of the Qing Empire after May 8, 1897, two years after the treaty came into force.[2]

The Nationality Law was promulgated by the Nationalist Government of the Republic of China (ROC) on 5 February 1929, after it replaced the Beiyang Government. At this time, Taiwan was still under Japanese rule. At the end of the World War II, Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945. The Nationalist government started the process to takeover Taiwan on behalf of the Allies. While deporting the Japanese people living in Taiwan (wansheng),[3] in a military order effective January 12, 1946, the ROC government announced that the people living in Taiwan had "regained" their status as ROC nationals, which gave rise to diplomatic protests from the United Kingdom and the United States.[4] The controversy continues until today due to the complex political status of Taiwan.

In 1949, the government of the Republic of China lost the Chinese Civil War and relocated to Taipei on December 7. The government only controls Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, and some other minor islands. This situation led to the whole revision of the Nationality Law by the Taipei-based Legislative Yuan in the 2000s, however there were no amendments addressing the mass naturalization of Taiwan persons as ROC nationals in 1946. The Nationality Law was last amended on December 21, 2016.

In the current law of Taiwan, nationality (國籍) makes no provision regarding citizenship. The Additional Articles of the Constitution restricts the citizenship rights, including civil and political rights, to persons with household registration in Taiwan (officially the Free area of the Republic of China). The Immigration Act[5] defines the nationals (國民) as persons who with nationality and household registration in Taiwan, and those National without household registration.

Nationality

The nationality law generally follows jus sanguinis. The law spells out four criteria, any one of which may be met to qualify for nationality:

- A person whose father or mother is, at the time of his (her) birth, a national of the Republic of China.

- A person born after the death of his (her) father or mother who was, at the time of his (her) death, a national of the Republic of China.

- A person born in the territory of the Republic of China and whose parents are both unknown or are stateless.

- A naturalized person.

In the original version of the law, nationality could only be passed from father to child. However, the law was revised in 2000 to allow citizenship to be passed on from either parent, taking effect on those born after 9 February 1980 (those under age 20 at the time of the promulgation).

Naturalization

There are two types of naturalization under the Nationality Law:

- Regular naturalization: Article 3, foreign nationals or stateless persons who currently have domicile in the territory of the Republic of China may apply for naturalization if they:

- have legally resided in the territory of the ROC for more than 183 days each year for at least five consecutive years;

- are aged 20 or above and legally competent in accordance with the laws of both the ROC and their original nation;

- have demonstrated good moral character and have no criminal record;

- possess sufficient property or professional skills to support themselves and lead a stable life; and

- possess basic proficiency in the national language of the ROC and basic knowledge of the rights and obligations of ROC nationals.

- Special naturalization: Article 4 to 6 lists various special conditions that foreign nationals or stateless persons may acquire nationality by naturalization.

Article 9 of the ROC Nationality Law requires prospective naturalized citizens to first renounce their previous nationality, possibly causing those persons to become stateless if they then fail to obtain ROC nationality.[6] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has noted that this has caused thousands of Vietnamese women to become stateless.[7] In December 2016, the Legislative Yuan waived Article 9 for the first time, for people who had made "special contributions" to Taiwan.[8] Promulgation of an amendment to Article 9 occurred in March 2017. The amendment states that foreigners who have lived in Taiwan for five years may apply for citizenship without losing their previous citizenship, given that applicants also have expertise in the areas of technology, economics, arts and culture, education, sports or a "special" category.[9]

Citizenship

In practice, exercise of most citizenship benefits, such as suffrage, and labour rights, requires possession of the National Identification Card, which is only issued to persons with household registration in the Taiwan Area aged 14 and older. Note that children of nationals who were born abroad are eligible for Taiwan passports and therefore considered to be nationals, but often they do not hold a household registration so are referred to as "unregistered nationals" in statute. These ROC nationals have no automatic right to stay in Taiwan, nor do they have working rights, voting rights, etc. In a similar fashion, some British passport holders do not have the right of abode in the UK (see British nationality law). Unregistered nationals can obtain a National Identification Card only by settling in Taiwan for one year without leaving, two consecutive years staying in Taiwan for a minimum of 270 days a year or five consecutive years staying 183 days or more in each year.

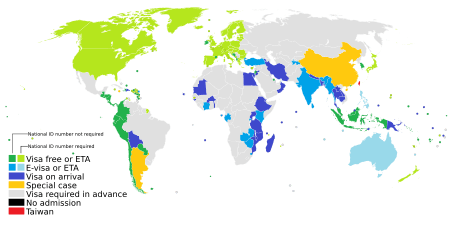

Travel freedom

Visa requirements for Taiwanese citizens are administrative entry restrictions by the authorities of other states placed on citizens of Taiwan. In 2014, Taiwanese citizens have visa-free or visa on arrival access to 167 countries and territories, ranking the Taiwan passport 26th in the world according to the Visa Restrictions Index.

Taiwan passport issues to overseas nationals is different than the type of passport issued to Taiwanese citizens with the former having far more restrictions than the latter. For instance, overseas nationals passport holders are required to apply for a visa to enter the Schengen area, whereas no visa is required for the regular passport holders. See the passport article for more information about this practice.

According to the standards and regulations of most international organizations, "Republic of China" is not a recognized nationality. In the international standard ISO 3166-1, the proper nationality designation for persons domiciled in Taiwan is not ROC, but rather TWN. This three-letter code TWN is also the official designation adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization [10] for use on a machine-readable travel document when dealing with entry/exit procedures at immigration authorities outside Taiwan.

Issues

Multiple citizenships

The Act does not restrict ROC nationals from acquiring multiple citizenships of other countries, however it requires the person to give up their original nationality upon naturalisation. Dual nationals are however restricted by Article 20 from holding most public offices in Taiwan. Indeed, many immigrants to Taiwan give up their original nationality, obtain ROC nationality, then apply again for their original nationality—which some countries will restore, some after a waiting period. (Notably, the United States government has no such procedure.) This entire process is fully legal under ROC law, though statistics are not available regarding how many people do this. The Act also permits former nationals of the ROC to apply for restoration of their nationality.

Nationals of the People's Republic of China

The government of the Republic of China does not recognise the People's Republic of China. It claims its official borders encompass all territories governed by the People's Republic of China and persons of these territories are considered to be nationals of the Republic of China. Thus, if the residents of the People's Republic of China (including Hong Kong and Macau) want to travel to Taiwan, they must do so using the Exit & Entry Permit. Chinese passports, Hong Kong SAR passports, Macau SAR passports, and BN(O) passports are generally not stamped by Taiwan immigration officers. Before 2002, Mongolia was also claimed to be part of the country, the government has affirmed its recognition that Mongolia is a sovereign state and permitted citizens of Mongolia to use their passports to enter Taiwan.

However, by Article 9-1, "[t]he people of the Taiwan Area may not have household registrations in the mainland China or hold passports issued by the Mainland China." If they obtain the passport of the PRC or household registration within mainland China, they will be deprived of their ROC Passport and household registration in Taiwan.[11] [12] It does not apply to Hong Kong and Macau in the sense that, if the residents of Hong Kong and Macau have settled permanently in Taiwan and gain citizenship rights as below, they are allowed to keep the passports as travel documents.

If the residents of the People's Republic of China (including Hong Kong and Macau) seek to settle permanently in Taiwan and gain citizenship rights, they do not naturalize like citizens of foreign countries. Instead, they merely can establish household registration, which in practice takes longer and is more complicated than naturalization. Article 9 does not apply to overseas Chinese holding foreign nationality who seek to exercise ROC nationality. Such persons do not need to naturalize because they are already legally ROC nationals. Residents of the People's Republic of China (including Hong Kong and Macau), only after gaining permanent resident status abroad, or otherwise establishing a period of residency defined by the regulations, they become eligible for a Taiwan passport but do not gain benefits of citizenship.

Overseas nationals

Nationals of the Republic of China with household registrations in the Taiwan Area are eligible for the Taiwan passport, and will lose the household registrations in the Taiwan Area, along with their ROC passport, upon holding the Chinese passport. They are different and mutually exclusive in law; most people living in Taiwan only will and only can choose one of these two to identify themselves by current laws.[11][12][13]

Taiwan passports are also issued to overseas Taiwanese and overseas Chinese as a proof of nationality, irrespective of whether they have lived or even set foot in Taiwan. The rationale behind this extension of the principle of jus sanguinis to almost all Chinese regardless of their countries of residence, as well as the recognition of dual citizenships, is to acknowledge the support given by overseas Chinese historically to the Kuomintang regime, particularly during the Xinhai Revolution. The type of passport issued to these individuals is called "Overseas Chinese Passport" of the Republic of China (僑民護照).

References

- "Nationality Law".

- 日治時期國籍選擇及戶籍處理

- "Memories preserved of Japanese born in Taiwan during colonial rule". Japan Times. 2 May 2018.

- Chen, Yi-nan (20 January 2011). "ROC forced citizenship on unwary Taiwanese". Taipei Times. p. 8. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Immigration Act

- "Not allowed to be Taiwanese". jidanni.org. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- "The Excluded: The strange hidden world of the stateless"Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, UNHCR Refugees Magazine Issue 147.

"Divorce leaves some Vietnamese women broken-hearted and stateless", 14 February 2007, unhcr.com - Chang, Jung-hsiang; Low, Y. F. (6 January 2017). "American priest gets ROC ID after 54 years". Central News Agency. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Chen, Yu-fu; Chin, Jonathan (24 March 2017). "Some immigrants no longer need to give up citizenship". Taipei Times. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- "Appendix 1, Three Letter Codes: Codes for designation of nationality, place of birth or issuing State/authority". Machine Readable Travel Documents (PDF). Section IV, Part 3, Volume 1 (Third ed.). Montreal, Quebec, Canada: International Civil Aviation Organization. 2008. ISBN 978-92-9231-139-1. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- "臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例".

- "Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area".

- "MAC urges public not to use Chinese passports - Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com.