Space Shuttle Columbia disaster

The Space Shuttle Columbia disaster was a fatal incident in the United States space program that occurred on February 1, 2003, when the Space Shuttle Columbia (OV-102) disintegrated as it reentered the atmosphere, killing all seven crew members. The disaster was the second fatal accident in the Space Shuttle program, after the 1986 breakup of Challenger soon after liftoff.

STS-107 flight insignia | |||||||||||||||

| Date | February 1, 2003 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 08:59 EST (13:59 UTC) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Over Texas and Louisiana | ||||||||||||||

| Cause | Wing damage from debris | ||||||||||||||

| Outcome | Shuttles grounded for 29 months | ||||||||||||||

| Deaths |

| ||||||||||||||

| Inquiries | Columbia Investigation Board | ||||||||||||||

During the launch of STS-107, Columbia's 28th mission, a piece of foam insulation broke off from the Space Shuttle external tank and struck the left wing of the orbiter. Similar foam shedding had occurred during previous shuttle launches, causing damage that ranged from minor to nearly catastrophic,[1][2] but some engineers suspected that the damage to Columbia was more serious. Before reentry, NASA managers had limited the investigation, reasoning that the crew could not have fixed the problem if it had been confirmed.[3] When Columbia reentered the atmosphere of Earth, the damage allowed hot atmospheric gases to penetrate the heat shield and destroy the internal wing structure, which caused the spacecraft to become unstable and break apart.[4]

After the disaster, Space Shuttle flight operations were suspended for more than two years, as they had been after the Challenger disaster. Construction of the International Space Station (ISS) was put on hold; the station relied entirely on the Russian Roscosmos State Space Corporation for resupply for 29 months until Shuttle flights resumed with STS-114 and 41 months for crew rotation until STS-121.

NASA ultimately made several technical and organizational changes, including adding a thorough on-orbit inspection to determine how well the shuttle's thermal protection system had endured the ascent, and keeping a designated rescue mission ready in case irreparable damage was found. Except for one final mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope, subsequent shuttle missions were flown only to the ISS so that the crew could use it as a haven if damage to the orbiter prevented safe reentry.

Crew

- Commander: Rick D. Husband, a U.S. Air Force colonel and mechanical engineer, who piloted a previous shuttle during the first docking with the International Space Station (STS-96)

- Pilot: William C. McCool, a U.S. Navy commander

- Payload commander: Michael P. Anderson, a U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel, physicist, and mission specialist who was in charge of the science mission and was on his second mission altogether (his first being STS-89)

- Payload specialist: Ilan Ramon, a colonel in the Israeli Air Force and the first Israeli astronaut.

- Mission specialist: Kalpana Chawla, aerospace engineer who was on her second space mission (her first being STS-87).

- Mission specialist: David M. Brown, a U.S. Navy captain trained as an aviator and flight surgeon. Brown worked on scientific experiments.

- Mission specialist: Laurel Blair Salton Clark, a U.S. Navy captain and flight surgeon. Clark worked on biological experiments.

Debris strike during launch

The shuttle's main fuel tank was covered in thermal insulation foam intended to prevent ice from forming when the tank is full of liquid hydrogen and oxygen. Such ice could damage the shuttle if shed during lift-off.

Mission STS-107 was the 113th Space Shuttle launch. Planned to begin on January 11, 2001, the mission was delayed 18 times[5] and eventually launched on January 16, 2003, following STS-113. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board determined these delays had nothing to do with the catastrophic failure.[5]

At 81.7 seconds after launch from Kennedy Space Center's LC-39-A, a suitcase-sized piece of foam broke off from the external tank (ET), striking Columbia's left wing reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) panels. As demonstrated by ground experiments conducted by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, it is likely that this created a six-to-ten-inch-diameter (15 to 25 cm) hole, allowing hot gases to enter the wing when Columbia later reentered the atmosphere. At the time of the foam strike, the orbiter was at an altitude of about 65,600 feet (20.0 km; 12.42 mi), traveling at Mach 2.46.

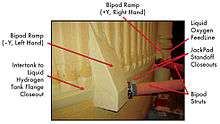

The left bipod foam ramp is an approximately three-foot-long (1 m) aerodynamic component made entirely of foam. The foam, not normally considered to be a structural material, is required to bear some aerodynamic loads. Because of these special requirements, the casting-in-place and curing of the ramps may be performed only by a senior technician.[6] The bipod ramp (having left and right sides) was originally designed to reduce aerodynamic stresses around the bipod attachment points at the external tank, but it was proven unnecessary in the wake of the accident and was removed from the external tank design for tanks flown after STS-107 (another foam ramp along the liquid oxygen line was also later removed from the tank design to eliminate it as a foam debris source, after analysis and tests proved this change safe).

Bipod ramp insulation had been observed falling off, in whole or in part, on four previous flights: STS-7 (1983), STS-32 (1990), STS-50 (1992), and most recently STS-112 (just two launches before STS-107). All affected shuttle missions completed successfully. NASA management referred to this phenomenon as "foam shedding". As with the O-ring erosion problems that ultimately doomed the Space Shuttle Challenger, NASA management became accustomed to these phenomena when no serious consequences resulted from these earlier episodes. This phenomenon was termed "normalization of deviance" by sociologist Diane Vaughan in her book on the Challenger launch decision process.[7]

As it happened, STS-112 had been the first flight with the "ET cam", a video feed mounted on the ET for the purpose of giving greater insight to the foam shedding problem. During that launch a chunk of foam broke away from the ET bipod ramp and hit the SRB-ET attachment ring near the bottom of the left solid rocket booster (SRB) causing a dent 4 in (100 mm) wide and 3 in (76 mm) inches deep in it.[8] After STS-112, NASA leaders analyzed the situation and decided to press ahead under the justification that "[t]he ET is safe to fly with no new concerns (and no added risk)" of further foam strikes.[9]

Video taken during lift-off of STS-107 was routinely reviewed two hours later and revealed nothing unusual. The following day, higher-resolution film that had been processed overnight revealed the foam debris striking the left wing, potentially damaging the thermal protection on the Space Shuttle.[10] At the time, the exact location where the foam struck the wing could not be determined due to the low resolution of the tracking camera footage.

Meanwhile, NASA's judgment about the risks was revisited. Linda Ham, chair of the Mission Management Team (MMT), said, "Rationale was lousy then and still is." Ham and Shuttle Program manager Ron Dittemore had both been present at the October 31, 2002, meeting where the decision to continue with launches was made.[11]

Post-disaster analysis revealed that two previous shuttle launches (STS-52 and -62) also had bipod ramp foam loss that went undetected. In addition, protuberance air load (PAL) ramp foam had also shed pieces, and there were also spot losses from large-area foams.

Flight risk management

In a risk-management situation similar to that of the Challenger disaster, NASA management failed to recognize the relevance of engineering concerns for safety and suggestions for imaging to inspect possible damage, and failed to respond to engineers' requests about the status of astronaut inspection of the left wing. Engineers made three separate requests for Department of Defense (DOD) imaging of the shuttle in orbit to determine damage more precisely. While the images were not guaranteed to show the damage, the capability existed for imaging of sufficient resolution to provide meaningful examination. NASA management did not accede to the requests, and in some cases intervened to stop the DOD from assisting.[12] The CAIB recommended subsequent shuttle flights be imaged while in orbit using ground-based or space-based DOD assets.[13] Details of the DOD's unfulfilled participation with Columbia remain secret; retired NASA official Wayne Hale stated in 2012 that "activity regarding other national assets and agencies remains classified and I cannot comment on that aspect of the Columbia tragedy".[14]

Throughout the risk assessment process, senior NASA managers were influenced by their belief that nothing could be done even if damage were detected. This affected their stance on investigation urgency, thoroughness and possible contingency actions. They decided to conduct a parametric "what-if" scenario study more suited to determine risk probabilities of future events, instead of inspecting and assessing the actual damage. The investigation report in particular singled out NASA manager Linda Ham for exhibiting this attitude.[15] In 2013, Hale recalled that Director of Mission Operations Jon C. Harpold shared with him before Columbia's destruction a mindset which Hale himself later agreed was widespread at the time, even among the astronauts themselves:[16]

You know, there is nothing we can do about damage to the [thermal protection system]. If it has been damaged it's probably better not to know. I think the crew would rather not know. Don't you think it would be better for them to have a happy successful flight and die unexpectedly during entry than to stay on orbit, knowing that there was nothing to be done, until the air ran out?

Much of the risk assessment hinged on damage predictions to the thermal protection system. These fall into two categories: damage to the silica tile on the wing lower surface, and damage to the reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) leading-edge panels. The TPS includes a third category of components, thermal insulating blankets, but damage predictions are not typically performed on them. Damage assessments on the thermal blankets can be performed after an anomaly has been observed, and this was done at least once after the return to flight following Columbia's loss.

Before the flight NASA believed that the RCC was very durable. Charles F. Bolden, who worked on tile-damage scenarios and repair methods early in his astronaut career, said in 2004 that "never did we talk about [the RCC] because we all thought that it was impenetrable":[17]

I spent fourteen years in the space program flying, thinking that I had this huge mass that was about five or six inches thick on the leading edge of the wing. And, to find after Columbia that it was fractions of an inch thick, and that it wasn't as strong as the Fiberglas[Note 1] on your Corvette, that was an eye-opener, and I think for all of us ... the best minds that I know of, in and outside of NASA, never envisioned that as a failure mode.

Damage-prediction software was used to evaluate possible tile and RCC damage. The tool for predicting tile damage was known as "Crater", described by several NASA representatives in press briefings as not actually a software program but rather a statistical spreadsheet of observed past flight events and effects. The "Crater" tool predicted severe penetration of multiple tiles by the impact if it struck the TPS tile area, but NASA engineers downplayed this. It had been shown that the model overstated damage from small projectiles, and engineers believed that the model would also overstate damage from larger Spray-On Foam Insulation (SOFI) impacts. The program used to predict RCC damage was based on small ice impacts the size of cigarette butts, not larger SOFI impacts, as the ice impacts were the only recognized threats to RCC panels up to that point. Under one of 15 predicted SOFI impact paths, the software predicted an ice impact would completely penetrate the RCC panel. Engineers downplayed this, too, believing that impacts of the less dense SOFI material would result in less damage than ice impacts. In an e-mail exchange, NASA managers questioned whether the density of the SOFI could be used as justification for reducing predicted damage. Despite engineering concerns about the energy imparted by the SOFI material, NASA managers ultimately accepted the rationale to reduce predicted damage of the RCC panels from possible complete penetration to slight damage to the panel's thin coating.[18]

Ultimately the NASA Mission Management Team felt there was insufficient evidence to indicate that the strike was an unsafe situation, so they declared the debris strike a "turnaround" issue (not of highest importance) and denied the requests for the Department of Defense images.

On January 23, flight director Steve Stich sent an e-mail to Columbia, informing commander Husband and pilot McCool of the foam strike while unequivocally dismissing any concerns about entry safety.[19][20]

During ascent at approximately 80 seconds, photo analysis shows that some debris from the area of the -Y ET Bipod Attach Point came loose and subsequently impacted the orbiter left wing, in the area of transition from Chine to Main Wing, creating a shower of smaller particles. The impact appears to be totally on the lower surface and no particles are seen to traverse over the upper surface of the wing. Experts have reviewed the high speed photography and there is no concern for RCC or tile damage. We have seen this same phenomenon on several other flights and there is absolutely no concern for entry.[21]

Reentry timeline

Columbia was scheduled to land at 09:16 EST.[Note 2]

- 02:30 EST, February 1, 2003: The Entry Flight Control Team began duty in the Mission Control Center.

- The Flight Control Team had not been working on any issues or problems related to the planned de-orbit and reentry of Columbia. In particular, the team had indicated no concerns regarding the debris that hit the left wing during ascent, and treated the reentry like any other. The team worked through the de-orbit preparation checklist and reentry checklist procedures. Weather forecasters, with the help of pilots in the Shuttle Training Aircraft, evaluated landing-site weather conditions at the Kennedy Space Center.

- 08:00: Mission Control Center Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain polled the Mission Control room for a decision for the de-orbit burn.

- All weather observations and forecasts were within guidelines set by the flight rules, and all systems were normal.

- 08:10: The Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) (and astronaut) Charles O. Hobaugh told the crew that they were "go" for de-orbit burn.

- 08:15:30 (EI-1719): Husband and McCool executed the de-orbit burn using Columbia's two Orbital Maneuvering System engines.

- The Orbiter was upside down and tail-first over the Indian Ocean at an altitude of 175 miles (282 km) and speed of 17,500 miles per hour (28,200 km/h) when the burn was executed. A 2-minute, 38-second de-orbit burn during the 255th orbit slowed the Orbiter to begin its reentry into the atmosphere. The burn proceeded normally, putting the crew under about one-tenth gravity. Husband then turned Columbia right side up, facing forward with the nose pitched up.

- 08:44:09 (EI+000): Entry Interface (EI), arbitrarily defined as the point at which the Orbiter entered the discernible atmosphere at 400,000 feet (120 km; 76 mi), occurred over the Pacific Ocean.

- As Columbia descended, the heat of reentry caused wing leading-edge temperatures to rise steadily, reaching an estimated 2,500 °F (1,370 °C) during the next six minutes. Former Space Shuttle Program Manager Wayne Hale said in a press briefing that about 90% of this heating is the result of compression of the atmospheric gas caused by the orbiter's supersonic flight, rather than the result of friction.

- 08:48:39 (EI+270): A sensor on the left wing leading edge spar showed strains higher than those seen on previous Columbia reentries.

- This was recorded only on the Modular Auxiliary Data System, which is similar to a flight data recorder, and was not sent to ground controllers or shown to the crew.

- 08:49:32 (EI+323): Columbia executed a planned roll to the right. Speed: Mach 24.5.

- Columbia began a banking turn to manage lift and therefore limit the Orbiter's rate of descent and heating.

- 08:50:53 (EI+404): Columbia entered a 10-minute period of peak heating, during which the thermal stresses were at their maximum. Speed: Mach 24.1; altitude: 243,000 feet (74 km; 46.0 mi).

- 08:52:00 (EI+471): Columbia was about 300 miles (480 km) west of the California coastline.

- The wing leading-edge temperatures usually reached 2,650 °F (1,450 °C) at this point.

- 08:53:26 (EI+557): Columbia crossed the California coast west of Sacramento. Speed: Mach 23; altitude: 231,600 feet (70.6 km; 43.86 mi).

- The Orbiter's wing leading edge typically reached more than 2,800 °F (1,540 °C) at this point.

- 08:53:46 (EI+577): Various people on the ground saw signs of debris being shed. Speed: Mach 22.8; altitude: 230,200 feet (70.2 km; 43.60 mi).

- The hot air surrounding the Orbiter suddenly brightened, causing a streak in the Orbiter's luminescent trail that was quite noticeable in the predawn skies over the West Coast. Observers witnessed four similar events during the following 23 seconds. Dialogue on some of the amateur footage indicates the observers were aware of the abnormality of what they were filming.

- 08:54:24 (EI+615): The MMACS officer, Jeff Kling, informed the Flight Director that "four hydraulic fluid temperature sensors in the left wing had stopped reporting." In Mission Control, reentry had been proceeding normally up to this point.

- 08:54:25 (EI+616): Columbia crossed from California into Nevada airspace. Speed: Mach 22.5; altitude: 227,400 feet (69.3 km; 43.07 mi).

- Witnesses observed a bright flash at this point and 18 similar events in the next four minutes.

- 08:55:00 (EI+651): Nearly 11 minutes after Columbia reentered the atmosphere, wing leading-edge temperatures normally reached nearly 3,000 °F (1,650 °C).

- 08:55:32 (EI+683): Columbia crossed from Nevada into Utah. Speed: Mach 21.8; altitude: 223,400 feet (68.1 km; 42.31 mi).

- 08:55:52 (EI+703): Columbia crossed from Utah into Arizona.

- 08:56:30 (EI+741): Columbia began a roll reversal, turning from right to left over Arizona.

- 08:56:45 (EI+756): Columbia crossed from Arizona to New Mexico. Speed: Mach 20.9; altitude: 219,000 feet (67 km; 41.5 mi).

- 08:57:24 (EI+795): Columbia passed just north of Albuquerque.

- 08:58:00 (EI+831): At this point, wing leading-edge temperatures typically decreased to 2,880 °F (1,580 °C).

- 08:58:20 (EI+851): Columbia crossed from New Mexico into Texas. Speed: Mach 19.5; altitude: 209,800 feet (63.9 km; 39.73 mi).

- At about this time, the Orbiter shed a Thermal Protection System tile, the most westerly piece of debris that has been recovered. Searchers found the tile in a field in Littlefield, Texas, just northwest of Lubbock.

- 08:59:15 (EI+906): MMACS informed the Flight Director that "pressure readings on both left main landing-gear tires were indicating 'off-scale low'."

- "Off-scale low" is a reading that falls below the minimum capability of the sensor, and it usually indicates that the sensor has stopped functioning, due to internal or external factors, not that the quantity it measures is actually below the sensor's minimum response value.

- 08:59:32 (EI+923): A broken response from mission commander Rick Husband was recorded: "Roger, uh, bu – [cut off in mid-word] ..." It was the last communication from the crew and the last telemetry signal received in Mission Control. The Flight Director then instructed the Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) to let the crew know that Mission Control saw the messages and was evaluating the indications, and added that the Flight Control Team did not understand the crew's last transmission.

- 08:59:37 (EI+928): Hydraulic pressure, which is required to move the flight control surfaces, was lost at about 08:59:37. At that time, the Master Alarm would have sounded for the loss of hydraulics, used to move flight control surfaces. The shuttle would have started to roll and yaw uncontrollably, and the crew would have become aware of the serious problem.[24]

- 09:00:18 (EI+969): Videos and eyewitness reports by observers on the ground in and near Dallas indicated that the Orbiter had disintegrated overhead, continued to break up into smaller pieces, and left multiple ion trails, as it continued eastward. In Mission Control, while the loss of signal was a cause for concern, there was no sign of any serious problem. Before the orbiter broke up at 09:00:18, the Columbia cabin pressure was nominal and the crew was capable of conscious actions.[24] Although the crew module remained mostly intact through the breakup, it was damaged enough that it lost pressure at a rate fast "enough to incapacitate the crew within seconds",[25] and was completely depressurized no later than 09:00:53.

- 09:00:57 (EI+1008): The crew module, intact to this point, was seen breaking into small subcomponents. It disappeared from view at 09:01:10. The crew members, if not already dead, were killed no later than this point.

- 09:05: Residents of north central Texas, particularly near Tyler, reported a loud boom, a small concussion wave, smoke trails and debris in the clear skies above the counties east of Dallas.

- 09:12:39 (EI+1710): After hearing of reports of the orbiter being seen to break apart, Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain declared a contingency (events leading to loss of the vehicle) and alerted search-and-rescue teams in the debris area. He called on the Ground Control Officer to "lock the doors", meaning no one would be permitted to enter or leave until everything needed for investigation of the accident had been secured.[26] Two minutes later, Mission Control put contingency procedures into effect.

Crew survivability aspects

In 2008, NASA released a detailed report on survivability aspects of the Columbia reentry.[27] In 2014, NASA released a further report detailing the aeromedical aspects of the disaster.[28] The crew were exposed to five lethal events[28]:88 in the following order:

Depressurization

After the initial loss of control, Columbia's cabin pressure remained normal, and the crew were not incapacitated.[27]:2-88 During this period the crew attempted to regain control of the shuttle.[27]:3-70 As Columbia spun out of control, aerodynamic forces caused the orbiter to yaw to the right, exposing its underside to extreme aerodynamic forces and causing it to break up. Depressurization began when the shuttle forebody separated from the midbody 41 seconds after loss of control. The crew module pressure vessel was penetrated when it collided with the fuselage, and the "depressurization rate was high enough to incapacitate the crew members within seconds so that they were unable to perform actions such as lowering their visors." The crew lost consciousness, suffering massive pulmonary barotrauma, ebullism and cessation of respiration.[28]:89,101-103

Off-nominal dynamic G environment

The shuttle's separated nose section rotated unsteadily about all three axes. The crew (now unconscious or dead) were unable to brace against this motion, and were also harmed by aspects of their protective equipment:

- Lack of upper-body and limb restraints: the crew's torsos were free to move because the strap velocity was lower than the locking threshold velocity of the inertia reel system, and because the seat restraints did not prevent lateral movement. Fractures consistent with flailing arms and legs were also observed.[28]:91,105-106

- Non-conformal helmets: unlike a racing helmet, the ACES suit helmets allowed the crew's heads to move inside the helmet, causing blunt force trauma during collisions. The helmet neck ring acted as a fulcrum for cervical vertebrae fractures as the skull whipped backwards, as well as inflicting jaw injuries when wind blasted the helmet off.[28]:105,104,111

Separation of the crew members from the crew module and the seats

As the crew module disintegrated, the crew received lethal trauma from their seat restraints and were exposed to the hostile aerodynamic and thermal environment of reentry, as well as molten Columbia debris.[28]:92,108-110

Exposure to high-speed and high-altitude environment

After separation from the crew module, the bodies of the crew members entered an environment with almost no oxygen, very low atmospheric pressure, and both high temperatures caused by deceleration, and extremely low ambient temperatures.[28]:93 NASA stated that despite not being certified for those conditions, the ACES suit "may potentially be capable of protecting the crew" above 100,000 feet, [27]:1-29 although in Columbia's case the crew's suits had already been destroyed by the cabin's thermal environment during breakup. Recovered tissue samples showed evidence of ebullism, indicating the crew was exposed to an altitude above 63,500 feet when depressurization of the cabin occurred.[27]:3-71

Ground impact

The bodies of the crew members "had lethal-level injuries caused by ground impact."[28]:94 The official NASA report omitted some of the more graphic details on the recovery of the remains; witnesses reported finds such as a skull, human heart, a portion of an upper torso, and parts of femur bones.[29]

All evidence indicated that crew error was in no way responsible for the disintegration of the orbiter, and they had acted correctly and according to procedure at the first indication of trouble. Although some of the crew were not wearing gloves or helmets during reentry and some were not properly restrained in their seats, doing these things would have added nothing to their survival chances other than perhaps keeping them alive and conscious another 30 or so seconds.[30]

Presidential response

At 14:04 EST (19:04 UTC), President George W. Bush said, "My fellow Americans, this day has brought terrible news, and great sadness to our country. At 9 o'clock this morning, Mission Control in Houston lost contact with our Space Shuttle Columbia. A short time later, debris was seen falling from the skies above Texas. The Columbia is lost; there are no survivors." Despite the disaster, Bush said, "The cause in which they died will continue...Our journey into space will go on."[31] Bush later declared East Texas a federal disaster area, allowing federal agencies to help with the recovery effort.[32]

Recovery of debris

Debris from the spacecraft was found in more than 2,000 separate fields in eastern Texas, western Louisiana and the southwestern counties of Arkansas. A large amount of debris was recovered between Tyler, Texas, and Palestine, Texas. One field stretched from south of Fort Worth to Hemphill, Texas, and into Louisiana.[33] Places that had debris included Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas, and several casinos in Shreveport, Louisiana.[33]

Along with pieces of the shuttle and bits of equipment, searchers also found human body parts, including arms, feet, a torso, and a heart.[34] These recoveries occurred along a line south of Hemphill, Texas and west of the Toledo Bend Reservoir.[35] Much of the terrain being searched for the crew was densely forested and difficult to traverse. The bodies of five of the seven crew of Columbia were found within three days of the shuttle's breakup; the last two were found 10 days after that.[35]

In the months after the disaster, the largest-ever organized ground search took place.[36] Thousands of volunteers descended upon Texas to participate in the effort to gather the Shuttle's remains. According to Mike Ciannilli, Project Manager of the Columbia Research and Preservation Office, the searchers "put their life on hold to help out the nation's space program," showing "what space means to people."[37] NASA issued warnings to the public that any debris could contain hazardous chemicals, that it should be left untouched, its location reported to local emergency services or government authorities, and that anyone in unauthorized possession of debris would be prosecuted. Some firefighters used Geiger counters to test those who had picked up debris. These same people were also asked to put their clothes into medical waste bags and use anti-microbial soap.[38] Because of the widespread area, volunteer amateur radio operators accompanied the search teams to provide communications support.[39]

A group of small (one-millimeter or 0.039-inch) adult Caenorhabditis elegans worms, living in petri dishes enclosed in aluminum canisters, survived reentry and impact with the ground and were recovered weeks after the disaster.[40][41] The culture was found to be alive on April 28, 2003.[42] The worms were part of a biological research in canisters experiment designed to study the effect of weightlessness on physiology; the experiment was conducted by Cassie Conley, NASA's planetary protection officer.

Debris Search Pilot Jules F. Mier Jr. and Debris Search Aviation Specialist Charles Krenek died in a helicopter crash that injured three others during the search.[43]

Some Texas residents recovered some of the debris, ignoring the warnings, and attempted to sell it on the online auction site eBay, starting at $10,000. The auction was quickly removed, but prices for Columbia merchandise such as programs, photographs and patches, went up dramatically following the disaster, creating a surge of Columbia-related listings.[44] A three-day amnesty offered for "looted" shuttle debris brought in hundreds of illegally recovered pieces.[45] During the amnesty period, "quite a few" individuals called about turning in property to NASA, including some who had debris from the Challenger accident.[46]

About 40,000 recovered pieces of debris have never been identified.[47] The largest pieces recovered include the front landing gear[48] and a window frame.[49]

On May 9, 2008, it was reported that data from a disk drive on board Columbia had survived the shuttle accident, and while part of the 340 MB drive was damaged, 99% of the data was recovered.[50] The drive was used to store data from an experiment on the properties of shear thinning.[51]

On July 29, 2011, Nacogdoches authorities told NASA that a four-foot-diameter (1.2 m) piece of debris had been found in a lake. NASA identified the piece as a power reactant storage and distribution tank.[52]

All recovered non-human Columbia debris is stored in unused office space at the Vehicle Assembly Building, except for parts of the crew compartment, which are kept separate.[53]

Crew cabin video

Among the recovered items was a videotape recording made by the astronauts during the start of reentry. The 13-minute recording shows the flight crew astronauts conducting routine reentry procedures and joking with each other. None gives any indication of a problem. In the video, the flight-deck crew puts on their gloves and passes the video camera around to record plasma and flames visible outside the windows of the orbiter, a normal occurrence during reentry. At one point on the tape, Mission Control asked Clark to perform some small task. She replied that she was currently occupied but would get to it in a minute. "Don't worry about it," she was told. "You have all the time in the world." The recording, which on normal flights would have continued through landing, ends about four minutes before the shuttle began to disintegrate and 11 minutes before Mission Control lost the signal from the orbiter.[54][55]

Investigation

Initial investigation

NASA Space Shuttle Program Manager Ron Dittemore reported that "The first indication was loss of temperature sensors and hydraulic systems on the left wing. They were followed seconds and minutes later by several other problems, including loss of tire pressure indications on the left main gear and then indications of excessive structural heating".[56] Analysis of 31 seconds of telemetry data which had initially been filtered out because of data corruption within it showed the shuttle fighting to maintain its orientation, eventually using maximum thrust from its Reaction Control System jets.

The investigation focused on the foam strike from the very beginning. Incidents of debris strikes from ice and foam causing damage during take-off were already well known, and had damaged orbiters, most noticeably during STS-45, STS-27, and STS-87.[57] After the loss of Columbia, NASA incorrectly concluded that mistakes during installation were the likely cause of foam loss, and retrained employees at Michoud Assembly Facility in Louisiana to apply foam without defects.[14] Tile damage had also been traced to ablating insulating material from the cryogenic fuel tank in the past.

Columbia Accident Investigation Board

Following protocols established after the loss of Challenger, an independent investigating board was created immediately after the accident. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board, or CAIB, was chaired by retired U.S. Navy Admiral Harold W. Gehman, Jr.,[58] and consisted of expert military and civilian analysts who investigated the accident in detail.

Columbia's flight data recorder was found near Hemphill, Texas, on March 19, 2003.[59] Unlike commercial jet aircraft, the space shuttles did not have flight data recorders intended for after-crash analysis. Instead, the vehicle data were transmitted in real time to the ground via telemetry. Since Columbia was the first shuttle, it had a special flight data OEX (Orbiter EXperiments) recorder, designed to help engineers better understand vehicle performance during the first test flights. The recorder was left in Columbia after the initial Shuttle test-flights were completed, and it was still functioning on the crashed flight. It recorded many hundreds of parameters, and contained very extensive logs of structural and other data, which allowed the CAIB to reconstruct many of the events during the process leading to breakup.[60] Investigators could often use the loss of signals from sensors on the wing to track how the damage progressed.[61] This was correlated with forensic debris analysis conducted at Lehigh University and other tests to obtain a final conclusion about the probable course of events.[62]

Beginning on May 30, 2003, foam impact tests were performed by Southwest Research Institute. They used a compressed air gun to fire a foam block of similar size and mass to that which struck Columbia, at the same estimated speed. To represent the leading edge of Columbia's left wing, RCC panels from NASA stock, along with the actual leading-edge panels from Enterprise , which were fiberglass, were mounted to a simulating structural metal frame. At the beginning of testing, the likely impact site was estimated to be between RCC panel 6 and 9, inclusive. Over many days, dozens of the foam blocks were shot at the wing leading edge model at various angles. These produced only cracks or surface damage to the RCC panels.

During June, further analysis of information from Columbia's flight data recorder narrowed the probable impact site to one single panel: RCC wing panel 8. On July 7, in a final round of testing, a block fired at the side of an RCC panel 8 created a hole 16 by 16.7 inches (41 by 42 cm) in that protective RCC panel.[63] The tests demonstrated that a foam impact of the type Columbia sustained could seriously breach the thermal protection system on the wing leading edge.[64]

Conclusions

On August 26, 2003, the CAIB issued its report on the accident. The report confirmed the immediate cause of the accident was a breach in the leading edge of the left wing, caused by insulating foam shed during launch. The report also delved deeply into the underlying organizational and cultural issues that led to the accident. The report was highly critical of NASA's decision-making and risk-assessment processes. It concluded the organizational structure and processes were sufficiently flawed that a compromise of safety was expected, no matter who was in the key decision-making positions. An example was the position of Shuttle Program Manager, where one individual was responsible for achieving safe, timely launches and acceptable costs, which are often conflicting goals. The CAIB report found that NASA had accepted deviations from design criteria as normal when they happened on several flights and did not lead to mission-compromising consequences. One of those was the conflict between a design specification stating that the thermal protection system was not designed to withstand significant impacts and the common occurrence of impact damage to it during flight. The board made recommendations for significant changes in processes and organizational culture.

On December 30, 2008, NASA released a further report, titled Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report, produced by a second commission, the Spacecraft Crew Survival Integrated Investigation Team (SCSIIT). NASA had commissioned this group, "to perform a comprehensive analysis of the accident, focusing on factors and events affecting crew survival, and to develop recommendations for improving crew survival for all future human space flight vehicles."[65] The report concluded that: "The Columbia depressurization event occurred so rapidly that the crew members were incapacitated within seconds, before they could configure the suit for full protection from loss of cabin pressure. Although circulatory systems functioned for a brief time, the effects of the depressurization were severe enough that the crew could not have regained consciousness. This event was lethal to the crew."

The report also concluded:

- The crew did not have time to prepare themselves. Some crew members were not wearing their safety gloves, and one crew member was not wearing a helmet. New policies gave the crew more time to prepare for descent.

- The crew's safety harnesses malfunctioned during the violent descent. The harnesses on the three remaining shuttles were upgraded after the accident.

The key recommendations of the report included that future spacecraft crew survival systems should not rely on manual activation to protect the crew.[66]

Other contributing factors

Upgrades to the leading edge proposed in the early 1990s were not funded because NASA was working on the later-cancelled VentureStar single-stage-to-orbit shuttle replacement.[67] Additionally, the original white paint on the fuel tanks was removed to save 600 lb (270 kg), exposing the rust-orange-colored foam; this was considered as a potential contributing factor, but was ultimately unlikely to have contributed to the foam shedding.[68]

Possible emergency procedures

One question of special importance was whether NASA could have saved the astronauts had they known of the danger.[69] This would have to involve either rescue or repair – docking at the International Space Station for use as a haven while awaiting rescue (or to use the Soyuz to systematically ferry the crew to safety) would have been impossible due to the different orbital inclination of the vehicles.

The CAIB determined that a rescue mission, though risky, might have been possible provided NASA management had taken action soon enough.[70][71] Normally, a rescue mission is not possible, due to the time required to prepare a shuttle for launch, and the limited consumables (power, water, air) of an orbiting shuttle. Atlantis was well along in processing for a planned March 1 launch on STS-114, and Columbia carried an unusually large quantity of consumables due to an Extended Duration Orbiter package. The CAIB determined that this would have allowed Columbia to stay in orbit until flight day 30 (February 15). NASA investigators determined that Atlantis processing could have been expedited with no skipped safety checks for a February 10 launch. Hence, if nothing went wrong, there was a five-day overlap for a possible rescue. As mission control could deorbit an empty shuttle, but could not control the orbiter's reentry and landing, it is likely that it would have sent Columbia into the Pacific Ocean;[71] NASA later developed the Remote Control Orbiter system to permit mission control to land a shuttle.

NASA investigators determined that on-orbit repair by the shuttle astronauts was possible but overall considered "high risk", primarily due to the uncertain resiliency of the repair using available materials and the anticipated high risk of doing additional damage to the Orbiter.[70][71] Columbia did not carry the Canadarm, or Remote Manipulator System, which would normally be used for camera inspection or transporting a spacewalking astronaut to the wing. Therefore, an unusual emergency extra-vehicular activity (EVA) would have been required. While there was no astronaut EVA training for maneuvering to the wing, astronauts are always prepared for a similarly difficult emergency EVA to close the external tank umbilical doors located on the orbiter underside, which is necessary for reentry in the event of failure. Similar methods could have reached the shuttle left wing for inspection or repair.[71]

For the repair, the CAIB determined that the astronauts would have to use tools and small pieces of titanium, or other metal, scavenged from the crew cabin. These metals would help protect the wing structure and would be held in place during reentry by a water-filled bag that had turned into ice in the cold of space. The ice and metal would help restore wing leading edge geometry, preventing a turbulent airflow over the wing and therefore keeping heating and burn-through levels low enough for the crew to survive reentry and bail out before landing. The CAIB could not determine whether a patched-up left wing would have survived even a modified reentry, and concluded that the rescue option would have had a considerably higher chance of bringing Columbia's crew back alive.[70][71]

Memorials

On February 2, 2003, and throughout March, April, and May 2003, large memorial Catholic Brazilian masses and Roman Catholic memorial concerts were held in Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, and other cities in Brazil where Brazilian Catholic priest Marcelo Rossi and his concert partner Belo sang a Christian hymn "Noites Traicoeiras" (Treacherous Nights) as tribute to the seven Columbia astronauts, as well as the other seven crew members who lost their lives in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986. The concerts were televised to millions throughout Brazil and the world.

On February 4, 2003, President George W. Bush and his wife Laura led a memorial service for the astronauts' families at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Two days later, Vice President Dick Cheney and his wife Lynne led a similar service at Washington National Cathedral. Patti LaBelle sang "Way Up There" as part of the service.[72]

On March 26, the United States House of Representatives' Science Committee approved funds for the construction of a memorial at Arlington National Cemetery for the STS-107 crew. A similar memorial was built at the cemetery for the last crew of Challenger. On October 28, 2003, the names of the astronauts were added to the Space Mirror Memorial at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Merritt Island, Florida, alongside the names of several astronauts and cosmonauts who have died in the line of duty.

On April 1, 2003, the Opening Day of baseball season, the Houston Astros (named in honor of the U.S. space program) honored the Columbia crew by having seven simultaneous first pitches thrown by family and friends of the crew. For the National Anthem, 107 NASA personnel, including flight controllers and others involved in Columbia's final mission, carried a U.S. flag onto the field. In addition, the Astros wore the mission patch on their sleeves and replaced all dugout advertising with the mission patch logo for the entire season.[73]

On February 1, 2004, the first anniversary of the Columbia disaster, Super Bowl XXXVIII held in Houston's Reliant Stadium began with a pregame tribute to the crew of the Columbia by singer Josh Groban performing "You Raise Me Up", with the crew of STS-114, the first post-Columbia Space Shuttle mission, in attendance.[74][75]

In 2004, Bush conferred posthumous Congressional Space Medals of Honor to all 14 crew members lost in the Challenger and Columbia accidents.[76]

NASA named several places in honor of Columbia and the crew. Seven asteroids discovered in July 2001 at the Mount Palomar observatory were officially given the names of the seven astronauts: 51823 Rickhusband, 51824 Mikeanderson, 51825 Davidbrown, 51826 Kalpanachawla, 51827 Laurelclark, 51828 Ilanramon, 51829 Williemccool.[77] On Mars, the landing site of the rover Spirit was named Columbia Memorial Station, and included a memorial plaque to the Columbia crew mounted on the back of the high gain antenna. A complex of seven hills east of the Spirit landing site was dubbed the Columbia Hills; each of the seven hills was individually named for a member of the crew, and Husband Hill in particular was ascended and explored by the rover. In 2006, the IAU approved naming of a cluster of seven small craters in the Apollo basin on the far side of the Moon after the astronauts.[78] Back on Earth, NASA's National Scientific Balloon Facility was renamed the Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility.

Other tributes included the decision by Amarillo, Texas, to rename its airport Rick Husband Amarillo International Airport after the Amarillo native. Washington State Route 904 was renamed Lt. Michael P. Anderson Memorial Highway, as it runs through Cheney, Washington, the town where he graduated from high school. A newly constructed elementary school located on Fairchild Air Force Base near Spokane, Washington, was named Michael Anderson Elementary School. Anderson had attended fifth grade at Blair Elementary, the base's previous elementary school, while his father was stationed there. A mountain peak near Kit Carson Peak and Challenger Point in the Sangre de Cristo Range was renamed Columbia Point, and a dedication plaque was placed on the point in August 2003. Seven dormitories were named in honor of Columbia crew members at the Florida Institute of Technology, Creighton University, The University of Texas at Arlington, and the Columbia Elementary School in the Brevard County School District. The Huntsville City Schools in Huntsville, Alabama, a city strongly associated with NASA, named their most recent high school Columbia High School as a memorial to the crew. A Department of Defense school in Guam was renamed Commander William C. McCool Elementary School.[79] The City of Palmdale, California, the birthplace of the entire shuttle fleet, changed the name of the thoroughfare Avenue M to Columbia Way. In Avondale, Arizona, the Avondale Elementary School where Michael Anderson's sister worked had sent a T-shirt with him into space. It was supposed to have an assembly when he returned from space. The school was later renamed Michael Anderson Elementary.

The first dedicated meteorological satellite launched by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) on September 2, 2002, named Metsat-1, was later renamed Kalpana-1 by Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in memory of India-born Kalpana Chawla.

In October 2004, both houses of Congress passed a resolution authored by U.S. Representative Lucille Roybal-Allard and co-sponsored by the entire contingent of California representatives to Congress changing the name of Downey, California's Space Science Learning Center to the Columbia Memorial Space Science Learning Center. The facility is located at the former manufacturing site of the space shuttles, including Columbia and Challenger.[80]

The U.S. Air Force's Squadron Officer School at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, renamed their auditorium in Husband's honor. He was a graduate of the program. The U.S. Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California named its pilot lounge for Husband.

NASA named a supercomputer "Columbia" in the crew's honor in 2004. It was located at the NASA Advanced Supercomputing Division at Ames Research Center on Moffett Federal Airfield near Mountain View, California. The first part of the system, built in 2003, known as "Kalpana" was dedicated to Chawla, who worked at Ames prior to joining the Space Shuttle program.[81]

A U.S. Navy compound at a major coalition military base in Afghanistan is named Camp McCool. In addition, the athletic field at McCool's alma mater, Coronado High School in Lubbock, Texas, was renamed the Willie McCool Track and Field.

A proposed reservoir in Cherokee County in Eastern Texas is to be named Lake Columbia.[82]

Ilan Ramon High School was established in 2006 in Hod HaSharon, Israel, in tribute to the first Israeli astronaut.[83] The school's symbol shows the planet Earth with an aircraft orbiting around it.[84]

The National Naval Medical Center dedicated Laurel Clark Memorial Auditorium on July 11, 2003.[85] Gamma Phi Beta sorority, of which Clark was a member, created the Laurel Clark Foundation in her honor.[86] A fountain in downtown Racine, Wisconsin, which Clark considered her hometown, was named for her.[87]

PS 58 in Staten Island, New York, was named Space Shuttle Columbia School in honor of the failed mission.[88]

The Challenger Columbia Stadium in League City, Texas is named in honor of the victims of both the Columbia disaster as well as the Challenger disaster in 1986.

A tree for each astronaut was planted in NASA's Astronaut Memorial Grove at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, not far from the Saturn V building, along with trees for each astronaut from the Apollo 1 and Challenger disasters.[89] Tours of the space center pause briefly near the grove for a moment of silence, and the trees can be seen from nearby NASA Road 1.

Columbia Colles, a range of hills on Pluto discovered by the New Horizons spacecraft in July 2015, was named in honor of the victims of the disaster.[90]

A starship on Star Trek: Enterprise was named NX-02 Columbia in honor of the Columbia.

A photo tribute commemorating the Columbia and its crew is displayed in the "Wings of Fame" section of the queue for Soarin' Around the World at Disney California Adventure park alongside many other famous air and space craft.[91]

The Columbia Memorial Space Center is a museum built in honor of the Columbia in Downey, California.

At the 2003 Daytona 500, which happened 2 weeks after the disaster, all racecars bore Columbia decals in honor of those who were lost.

Effect on space programs

Following the loss of Columbia, the space shuttle program was suspended.[61] The further construction of the International Space Station (ISS) was also delayed, as the space shuttles were the only available delivery vehicle for station modules. The station was supplied using Russian uncrewed Progress ships, and crews were exchanged using Russian-crewed Soyuz spacecraft, and forced to operate on a skeleton crew of two.[92][93]

Less than a year after the accident, President Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration, calling for the space shuttle fleet to complete the ISS, with retirement by 2010 following the completion of the ISS, to be replaced by a newly developed Crew Exploration Vehicle for travel to the Moon and Mars.[94] NASA planned to return the space shuttle to service around September 2004; that date was pushed back to July 2005.

On July 26, 2005, at 10:39 EST, Space Shuttle Discovery cleared the tower on the "Return to Flight" mission STS-114, marking the shuttle's return to space. Overall the STS-114 flight was highly successful, but a similar piece of foam from a different portion of the tank was shed, although the debris did not strike the Orbiter. Due to this, NASA once again grounded the shuttles until the remaining problem was understood and a solution implemented.[61] After delaying their reentry by two days due to adverse weather conditions, Commander Eileen Collins and Pilot James M. Kelly returned Discovery safely to Earth on August 9, 2005. Later that same month, the external tank construction site at Michoud was damaged by Hurricane Katrina.[95] At the time, there was concern that this would set back further shuttle flights by at least two months and possibly more.

The actual cause of the foam loss on both Columbia and Discovery was not determined until December 2005, when x-ray photographs of another tank showed that thermal expansion and contraction during filling, not human error, caused cracks that led to foam loss. NASA's Hale formally apologized to the Michoud workers who had been blamed for the loss of Columbia for almost three years.[14]

The second "Return to Flight" mission, STS-121, was launched on July 4, 2006, at 14:37:55 (EDT), after two previous launch attempts were scrubbed because of lingering thunderstorms and high winds around the launch pad. The launch took place despite objections from its chief engineer and safety head. This mission increased the ISS crew to three. A 5-inch (130 mm) crack in the foam insulation of the external tank gave cause for concern, but the Mission Management Team gave the go for launch.[96] Space Shuttle Discovery touched down successfully on July 17, 2006, at 09:14:43 (EDT) on Runway 15 at the Kennedy Space Center.

On August 13, 2006, NASA announced that STS-121 had shed more foam than they had expected. While this did not delay the launch for the next mission—STS-115, originally set to lift off on August 27 [97]—the weather and other technical glitches did, with a lightning strike, Hurricane Ernesto and a faulty fuel tank sensor combining to delay the launch until September 9. On September 19, landing was delayed an extra day to examine Atlantis after objects were found floating near the shuttle in the same orbit. When no damage was detected, Atlantis landed successfully on September 21.

The Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report released by NASA on December 30, 2008, made further recommendations to improve a crew's survival chances on future space vehicles, such as the then planned Orion spacecraft. These included improvements in crew restraints, finding ways to deal more effectively with catastrophic cabin depressurization, more "graceful degradation" of vehicles during a disaster so that crews will have a better chance at survival, and automated parachute systems.[65]

The United States ended its Space Shuttle program in 2011 in part due to the fallout from the Columbia disaster. No further crewed spacecraft were launched from American soil to the ISS until 2020 when SpaceX's Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission successfully carried a test crew of two NASA astronauts to the International Space Station.[98]

Sociocultural aftermath

Fears of terrorism

After the shuttle's breakup, there were some initial fears that terrorists might have been involved, but no evidence of that has ever surfaced.[99] Security surrounding the launch and landing of the space shuttle had been increased because the crew included the first Israeli astronaut.[100] The Merritt Island launch facility, like all sensitive government areas, had increased security after the September 11 attacks.

Purple streak image

The San Francisco Chronicle reported that an amateur astronomer had taken a five-second exposure that appeared to show "a purplish line near the shuttle", resembling lightning, during reentry.[101] The CAIB report concluded that the image was the result of "camera vibrations during a long-exposure".[102]

2003 Armageddon film hoax

In response to the disaster, FX canceled its scheduled airing two nights later of the 1998 film Armageddon, in which the Space Shuttle Atlantis is depicted as being destroyed by asteroid fragments.[103] In a hoax inspired by the destruction of Columbia, some images that were purported to be satellite photographs of the Shuttle's "explosion" turned out to be screen captures from the Space Shuttle destruction scene of Armageddon.[104]

Music

The 2003 album Bananas by Deep Purple includes "Contact Lost", an instrumental piece written by guitarist Steve Morse in remembrance of the loss. Morse is donating his songwriting royalties to the families of the astronauts.[105]

Catherine Faber and Callie Hills (the folk group known as Echo's Children) included a memorial song titled "Columbia" on their 2004 album From the Hazel Tree.[106]

The 2005 album Ultimatum by The Long Winters contains the song "The Commander Thinks Aloud", which was songwriter/singer John Roderick's musing on the crew's perspective of the unexpected catastrophe.[107] In addition, the January 30, 2015 episode of Hrishikesh Hirway's Song Exploder podcast presented an interview with John Roderick about the songwriting and recording process for "The Commander Thinks Aloud".[108]

The Hungarian composer Peter Eötvös wrote a piece named Seven for solo violin and orchestra in 2006 in memory of the crew of Columbia. Seven was premiered in 2007 by violinist Akiko Suwanai, conducted by Pierre Boulez, and it was recorded in 2012 with violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja and the composer conducting.[109]

The 2008 album Columbia: We Dare to Dream by Anne Cabrera was written as a tribute to Space Shuttle Columbia STS-107, the crew, support teams, recovery teams, and the crew's families.[110] A copy of the album on compact disc was flown aboard Space Shuttle Discovery mission STS-131 to the International Space Station by astronaut Clayton Anderson in April 2010.[111]

The Scottish Folk-Rock band Runrig included a song titled "Somewhere" on their album The Story (2016); the song was dedicated to Laurel Clark (who had become a fan of the band during her Navy service in Scotland), and includes a piece of her wake up song, followed by some radio chatter, at the end.[112]

Notes

- "Fiberglas" was the original name patented by Owens-Corning for its fiberglass insulating product in 1936.

- A timeline of STS-107, beginning at 8:10.39 and ending at 09:00.53, is available as part of NASA's post-disaster investigation.[22][23]

References

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (August 2003). "6.1 A History of Foam Anomalies (page 121)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- "Spaceflight Now | STS-119 Shuttle Report | Legendary commander tells story of shuttle's close call". spaceflightnow.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- Marcia Dunn (February 2, 2003). "Columbia's problems began on left wing". Associated Press via staugustine.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013.

- "Molten Aluminum found on Columbia's thermal tiles". USA Today. Associated Press. March 4, 2003. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (August 2003). "2.1 Mission Objectives and Their Rationales (page 28)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2006. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- Century of Flight. "The Columbia space shuttle accident". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (August 2003). "6.1 A History of Foam Anomalies (PDF)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- Armando Oliu; KSC Debris Team (October 10, 2002). "STS-112 SRB POST FLIGHT/RETRIEVAL ASSESSMENT" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- Jerry Smelser (October 31, 2002). "STS-112/ET-115 Bipod Ramp Foam Loss, Page 4" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 16, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Cabbage, Michael & Harwood, William (2004). Comm Check. Free Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-7432-6091-0.

- Gehman; et al. (2003). "Columbia Accident Investigation Board, Chapter 6, "A History of Foam Anomalies", pages 125 & 148" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "CAIB page 153 (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "CAIB Recommendation R6.3-2 (PDF)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2006.

- Hale, Wayne (April 18, 2012). "How We Nearly Lost Discovery". waynehale.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board, (2003) Volume 1, Chapter 6, p. 138. CAIB Report Volume 1 Part 2 Archived October 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine(pdf). Retrieved June 8, 2006.

- Hale, Wayne (January 13, 2013). "After Ten Years: Working on the Wrong Problem". Wayne Hale's Blog. Archived from the original on May 30, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- Bolden, Charles F. (January 6, 2004). "Charles F. Bolden". NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project (Interview). Interviewed by Johnson, Sandra; Wright, Rebecca; Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer. Houston, Texas. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "nasa-global.speedera.net" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

- "Email told fatal shuttle it was safe". AP/Guardian.co.uk. July 1, 2003. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- "Publicly released email exchange between Columbia and mission control". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- William Harwood (June 30, 2003). "Foam strike email to shuttle commander released". CBS News/spaceflightnow.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- "NASA Columbia Master Timeline". NASA. March 10, 2003. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- Troxell, Jennifer. "Columbia Chronology". NASA. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2008). "Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2016.

- "Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report, 2.3.3 Depressurization rate, Conclusion L1-5, pp 2-90" (PDF). NASA. 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "Report of Columbia Accident Investigation Board, Volume I". Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2006.

- "Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report" (PDF).

- Stepaniak, Philip C.; Lane, Helen W.; Davis, Jeffrey R. (May 2014). Loss of Signal: Aeromedical Lessons Learned from the STS-107 Columbia Space Shuttle Mishap (PDF). Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Harnden, Toby (February 3, 2003). "Searchers stumble on human remains". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bush, George W. (2003). "President Addresses Nation on Space Shuttle Columbia Tragedy". The White House. Archived from the original on February 11, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2006.

- Introduction to Emergency Management, Fourth Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann, Burlington, 2010, p. 166.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board, (2003) Volume 1, Chapter 2, p. 41.

- Harnden, Toby (February 3, 2003). "Searchers stumble on human remains". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017.

- Bringing Columbia Home (July 11, 2017), Farewell, Columbia - The recovery and reconstruction of space shuttle Columbia in 2003, retrieved May 25, 2019

- "In Search Of..." Archived from the original on March 20, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- Ramasamy Venugopal. "The Space Shuttle Columbia Disaster". Space Safety Magazine. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- Texas, By Toby Harnden in Norwood (February 3, 2003). "Searchers stumble on human remains". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- awextra@arrl.org (2003). "Hams Aid Columbia Debris Search in Western States". American Radio Relay League, Inc. Archived from the original on November 4, 2005. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- Szewczyk, Nathaniel; et al. (2005). "Caenorhabditis elegans Survives Atmospheric Breakup of STS-107, Space Shuttle Columbia". Mary Ann Liebert, Astrobiology. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- "Worms survived Columbia disaster". BBC News. May 1, 2003. Archived from the original on November 6, 2005. Retrieved December 16, 2005.

- Worms Survive Shuttle Disaster Archived October 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Fall 2003

- "The 'Columbia' Debris Recovery Helo Crash". Check-Six.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- "Shuttle debris offered online". BBC News. February 3, 2003. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- "Debris Amnesty Ends, 9 May Face Looting Charges". Associated Press. February 8, 2003.

- Stepaniak, Philip C.; Lane, Helen W., eds. (2014). Loss of Signal: Aeromedical Lessons Learned from the STS-107 Columbia Space Shuttle Mishap. NASA/SP-2014-616. p. 119.

During the moratorium quite a few individuals called about turning in property to NASA, including individuals who had debris from the Challenger accident.

- Barry, J. R.; Jenkins, D. R.; White, D. J.; Goodman, P. A.; Reingold, L. A.; Simon, A. H.; Kirchhoff, C. M. (February 1, 2003). "Columbia Accident Investigation Board Report. Volume Two". NTIS. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- "Divers Find Shuttle's Front Landing Gear". Fox News. February 19, 2003. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- "NASA begins packing up shuttle debris for storage". USA Today. September 10, 2003. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- Fonseca, Brian (May 7, 2008). "Shuttle Columbia's hard drive data recovered from crash site". Computerworld.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- "The Physics of Whipped Cream". Science.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- "Space shuttle Columbia part found in East Texas". CNN. August 2, 2011. Archived from the original on August 2, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- "Shuttle Columbia's Debris on View at NASA Facility". Los Angeles Times. January 31, 2004. Archived from the original on August 10, 2012.

- Glenn Mahone/Bob Jacobs (NASA Headquarters), Eileen M. Hawley (Johnson Space Center) (February 28, 2003). "NASA Releases Columbia Crew Cabin Video". NASA. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- "NASA Releases Columbia Crew Flight~Deck Video". YouTube AP Archive. July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- Dittemore, Ron (2003). "NASA Briefing, Part I". CNN. Archived from the original on February 9, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2006.

- Woods, David (2004). "Creating Foresight: Lessons for Enhancing Resilience from Columbia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2005. Retrieved February 1, 2005.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "Board Members". Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- NASA. "Review of Columbia's data recorder will begin this weekend". Archived from the original on March 29, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- Harwood, William (March 19, 2003). "Data recorder recovered; could hold key insights". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- Howell, Elizabeth. "Columbia Disaster: What Happened, What NASA Learned". Space. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- "Materials science students prepare to analyze debris recovered from the shuttle Columbia". Lehigh University. Archived from the original on September 12, 2006. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- Justin Kerr (2003). "Impact Testing of the Orbiter Thermal Protection System" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2006.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "Volume I, Chapter 3". Report of Columbia Accident Investigation Board (PDF). p. 78. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2005. Retrieved January 4, 2006.

- "Layout 1" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report Archived April 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- James Albaugh (December 4, 2017). "Opinion: Jim Albaugh's Lessons Of Aerospace Success". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017.

- "Columbia's White External Fuel Tanks". space.com. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- "The audacious rescue plan that might have saved space shuttle Columbia". Ars Technica. February 1, 2016. Archived from the original on September 29, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "Decision Making at NASA" (PDF). CAIB Report, Volume I, chapter 6.4 "Possibility of Rescue or Repair". pp. 173ff. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "STS-107 In-Flight Options Assessment" (PDF). CAIB Report, Volume II, appendix D.13. pp. 391ff. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 19, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2006.

- Woodruff, Judy (February 6, 2003). "Remembering the Columbia 7: Washington National Cathedral Memorial for Astronauts". CNN.com. CNN. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "Astros Honor Astronauts At Season Opener". NASA. Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- Babineck, Mark (February 1, 2004). "Columbia Astronauts Honored at Super Bowl". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

- "NFL honors shuttle crew in ceremony". Amarillo Globe-News. February 2, 2004. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

- "Congressional Space Medal of Honor". NASA History Program Office. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- "Asteroids Dedicated To Space Shuttle Columbia Crew" (Press release). NASA. August 6, 2003. Archived from the original on February 15, 2012.

"Tribute to the Crew of Columbia". Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2006. - Husband crater, Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, International Astronomical Union Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature

- "Commander William C. McCool Elementary/Middle School". Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- Barragan, James (February 14, 2014) "Downey space museum is struggling to survive" Archived April 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times

- "NASA to Name Supercomputer After Columbia Astronaut". Archived from the original on March 17, 2013.

- "The Lake Eastex Water Supply Project". Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- "Ramon High School-Overview". Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- "יום הבריאות 4.02.09". Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

- "Laurel B Clark Auditorium". Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- "MSU Gammas – Laurel Clark Foundation". Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- Fiori, Lindsay. "Laurel Clark Memorial Fountain features new additions" Archived August 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Racine Journal Times, May 27, 2008.

- "Welcome to PS 58". July 29, 2015. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015.

- Johnson Space Center (January 26, 2009). "NASA JSC Special: A Message From The Center Director: Memorials". SpaceRef.

- Sutherland, Paul. "Pluto team name features after Dr Who and Star Trek". Skymania. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "#soarinovercaliforniaphotos". Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- "Russian Soyuz TMA Spacecraft". NASA. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- Reichhardt, Tony (November 2003). "Backgrounder: State of the Station". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- "President Bush offers new vision for NASA". NASA. January 14, 2004. Archived from the original on May 10, 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- David, Leonard (August 30, 2005). "Katrina batters NASA facility". Space.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- Chien, Philip (June 27, 2006) "NASA wants shuttle to fly despite safety misgivings." Archived January 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine The Washington Times

- "Foam still a key concern for shuttle launch". New Scientist SPACE. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved August 13, 2006.

- "NASA And SpaceX Launch First Astronauts To Orbit From U.S. Since 2011". NPR.org. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Barnett, Brooke; Reynolds, Amy (2008). Terrorism and the Press: An Uneasy Relationship. Lang, Peter Publishing, Incorporated. p. 39. ISBN 0-8204-9516-6.

- "Israel mourns first astronaut's death". CNN. February 1, 2003. Archived from the original on April 20, 2004. Retrieved February 24, 2004.

- Russell, Sabin (May 2, 2003). "Mysterious purple streak is shown hitting Columbia 7 minutes before it disintegrated". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

- Columbia Accident Investigation Board (2003). "Volume III, Part 2". Report of Columbia Accident Investigation Board (PDF). p. 88. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2006. Retrieved August 18, 2006.

- Sue Chan (February 3, 2003). "TV Pulls Shuttle Sensitive Material". CBS News. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- "FACT CHECK: Space Shuttle Columbia Explosion". Snopes.com.

- "Deep Purple's Shuttle Connection". guitarsite.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- "Echo's Children CD Page". Archived from the original on February 11, 2015.

- Roderick, John. "The Long Winters". Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- Hirway, Hrishikesh. "Song Exploder, Episode 28: The Long Winters". Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- Eötvös, Peter. "Seven". Peter Eötvös. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- Cabrera, Anne. "Columbia: We Dare to Dream". Chubby Crow Records: Anne Cabrera. Chubby Crow Records Inc. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- Anderson, Clayton. "Clay Anderson with Columbia CD aboard ISS". Anderson. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- "Skye rockers Runrig prepare for their final album". Archived from the original on October 17, 2016.

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Space Shuttle Columbia disaster. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Orbiter Wing Leading Edge Protection (upgrade proposed for 1999, but cancelled)

- NASA's Space Shuttle Columbia and her crew

- NASA STS-107 Crew Memorial web page

- Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report PDF

- Doppler radar animation of the debris after break up

- President Bush's remarks at memorial service – February 4, 2003

- The CBS News Space Reporter's Handbook STS-51L/107 Supplement

- The 13-min. Crew cabin video (subtitled). Ends 4-min. before the Shuttle began to disintegrate.

- photos of recovered debris stored on the 16th floor of the Vehicle Assembly Building at KSC