Buran (spacecraft)

Buran (Russian: Бура́н, IPA: [bʊˈran], meaning "Snowstorm" or "Blizzard"; GRAU index serial number: 11F35 1K) was the first spaceplane to be produced as part of the Soviet/Russian Buran programme. Besides describing the first operational Soviet/Russian shuttle orbiter, "Buran" was also the designation for the entire Soviet/Russian spaceplane project and its orbiters, which were known as "Buran-class spaceplanes".

| Buran Буран | |

|---|---|

Buran at the 1989 Paris Air Show | |

| Country | |

| Named after | "Snowstorm"[1] |

| Status | Destroyed in a 2002 hangar collapse[2] |

| First flight | 1K1 15 November 1988[1] |

| Last flight | 1K1 15 November 1988[1] |

| No. of missions | 1[1] |

| Crew members | 0[1] |

| Time spent in space | 3 hours, 25 minutes, 22 seconds |

| No. of orbits | 2[1] |

Buran completed one uncrewed spaceflight in 1988, and was destroyed in 2002 when the hangar it was stored in collapsed.[3] The Buran-class orbiters used the expendable Energia rocket, a class of super heavy-lift launch vehicle.

Construction

The construction of the Buran spaceplanes began in 1980, and by 1984 the first full-scale orbiter was rolled-out. The Buran spaceplane was made to be launched on the Soviet Union's super-heavy lift vehicle, Energia. The Buran programme ended in 1993.[4]

| Date | Milestone[5][6] |

|---|---|

| 1980 | Assembly started |

| August 1983 | Fuselage delivery to NPO Energia |

| March 1984 | Start of comprehensive electrical testing |

| December 1984 | Delivery to Baikonur |

| April 1986 | Start of final assembly |

| 15 November 1987 | Final assembly completed |

| 15 November 1987-15 February 1988 | Testing in MIK OK |

| 19 May – 10 June 1988 | Test rollout |

| 15 November 1988 | Orbital flight (1K1) |

Operational history

Orbital flight

The only orbital launch of a Buran-class orbiter, 1K1 (first orbiter, first flight[7]) occurred at 03:00:02 UTC on 15 November 1988 from Baikonur Cosmodrome launch pad 110/37.[3][8] Buran was lifted into space, on an uncrewed mission, by the specially designed Energia rocket. The automated launch sequence performed as specified, and the Energia rocket lifted the vehicle into a temporary orbit before the orbiter separated as programmed. After boosting itself to a higher orbit and completing two orbits around the Earth, the ODU (Russian: объединённая двигательная установка, сombined propulsion system) engines fired automatically to begin the descent into the atmosphere, return to the launch site, and horizontal landing on a runway.[9]

After making an automated approach to Site 251,[3] Buran touched down under its own control at 06:24:42 UTC and came to a stop at 06:25:24,[10] 206 minutes after launch.[11] Despite a lateral wind speed of 61.2 kilometres per hour (38.0 mph), Buran landed only 3 metres (9.8 ft) laterally and 10 metres (33 ft) longitudinally from the target mark.[11][12] It was the first spaceplane to perform an uncrewed flight, including landing in fully automatic mode.[13] It was later found that Buran had lost only eight of its 38,000 thermal tiles over the course of its flight.[12]

Projected flights

In 1989, it was projected that Buran would have an uncrewed second flight by 1993, with a duration of 15–20 days.[7] Although the Buran programme was never officially cancelled, the dissolution of the Soviet Union led to funding drying up and this never took place.[4]

Specifications

The mass of Buran is quoted as 62 tons,[14] with a maximum payload of 30 tons, for a total lift-off weight of 105 tons.[4]

- Mass breakdown[3]

- Total mass of structure and landing systems: 42,000 kg (93,000 lb)

- Mass of functional systems and propulsion: 33,000 kg (73,000 lb)

- Maximum payload: 30,000 kg (66,000 lb)

- Maximum liftoff weight: 105,000 kg (231,000 lb)

- Length: 36.37 m (119.3 ft)

- Wingspan: 23.92 m (78.5 ft)

- Height on gear: 16.35 m (53.6 ft)

- Payload bay length: 18.55 m (60.9 ft)

- Payload bay diameter: 4.65 m (15.3 ft)

- Wing glove sweep: 78 degrees

- Wing sweep: 45 degrees

- Propulsion[4]

- Total orbital manoeuvering engine thrust: 17,600 kgf (173,000 N; 39,000 lbf)

- Orbital manoeuvering engine specific impulse: 362 seconds (3.55 km/s)

- Total manoeuvering impulse: 5 kgf-sec (11 lbf-sec)

- Total RCS thrust: 14,866 kgf (145,790 N; 32,770 lbf)

- Average RCS specific impulse: 275–295 seconds (2.70–2.89 km/s)

- Normal maximum propellant load: 14,500 kg (32,000 lb)

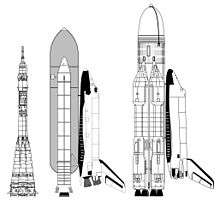

Unlike the US Space Shuttle, which was propelled by a combination of solid boosters and the orbiter's own liquid-propellant engines fuelled from a large tank, the Soviet/Russian shuttle system used thrust from each booster's four RD-170 liquid oxygen/kerosene engines, developed by Valentin Glushko, and another four RD-0120 liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen engines attached to the central block.[14]

Fate and destruction

In June 1989, Buran, carried on the back of the Antonov An-225, took part in the 1989 Paris Air Show at Le Bourget Airfield.

Together with the Energia rocket, Buran was put in a hangar at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan.

After the first flight of a Buran shuttle, the programme was suspended due to lack of funds and the political situation in the Soviet Union. The two subsequent orbiters, which were due in 1990 (informally Ptichka) and 1992 (informally Baikal) were never completed. The programme was officially terminated on 30 June 1993, by President Boris Yeltsin. At the time of its cancellation, 20 billion rubles had been spent on the Buran programme.[15]

On 12 May 2002, a hangar roof at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan collapsed because of a structural failure due to poor maintenance. The collapse killed 8 workers and destroyed one of the Buran craft (Orbiter K1), which flew the test flight in 1988, as well as a mock-up of an Energia booster rocket. [16]

Two further Buran shuttles (one for ground use and one that was 90% ready to spaceflight), together with an Energia-M rocket prototype carrier are still stored at the base, according to an article in 2017.[17]

See also

- Buran programme

- OK-GLI – Buran Analog BST-02 test vehicle

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-105 – Soviet orbital spaceplane

- Space Shuttle program (United States)

References

- "Buran". NASA. 12 November 1997. Archived from the original on 4 August 2006. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- "Eight feared dead in Baikonur hangar collapse". Spaceflight Now. 16 May 2002.

- Zak, Anatoly (25 December 2018). "Buran reusable orbiter". Russian Space Web. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Wade, Mark. "Buran". Encyclopedia Astronautics. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ""Reusable space system "Energia – Buran" (in russian)". Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "ground preparation". Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Экипажи "Бурана" Несбывшиеся планы". Buran.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- "S.P.Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation Energia held a ceremony..." Energia.ru. 14 November 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- Handwerk, Brian (12 April 2016). "The Forgotten Soviet Space Shuttle Could Fly Itself". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Buran-Energia: 1st Flight". Буран. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Chertok, Boris (2005). Siddiqi, Asif A. (ed.). Raketi i lyudi [Rockets and People] (PDF). History Series. NASA. p. 179.

- "Russia starts ambitious super-heavy space rocket project". Space Daily. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- "Largest spacecraft to orbit and land unmanned". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "The orbiters and the launch vehicle". Buran.su. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- Wade, Mark. "Yeltsin cancels Buran project". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 2 July 2006.

- Whitehouse, David (13 May 2002). "Russia's space dreams abandoned". BBC News. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- Prisco, Jacopo (21 December 2017). "Abandoned Soviet space shuttle left in Kazakh Steppe". CNN. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

Further reading

- Hendrickx, Bart; Vis, Bert (2007). Energiya-Buran: The Soviet Space Shuttle. Springer-Praxis. p. 526. Bibcode:2007ebss.book.....H. ISBN 978-0-387-69848-9.

- Elser, Heinz; Elser-Haft, Margrit; Lukashevich, Vladim (2008). History and Transportation of the Russian Space Shuttle OK-GLI to the Technik Museum Speyer. Technik Museum Speyer. ISBN 978-3-9809437-7-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buran 1.01. |

- Buran.ru

- Buran-Energia.com

- Buran schematic diagram

- Buran: The Soviet Space Shuttle Success Story at TASS.com(in English)

- Photos from the abandoned Buran facilities at Baikonur by Ralph Mirebs

- Photos of the destroyed Buran orbiter at Aviationweek.com