Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan

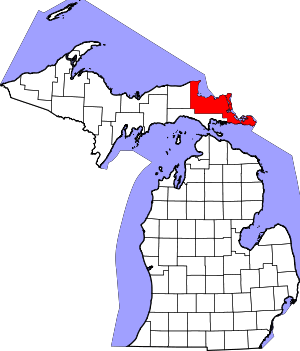

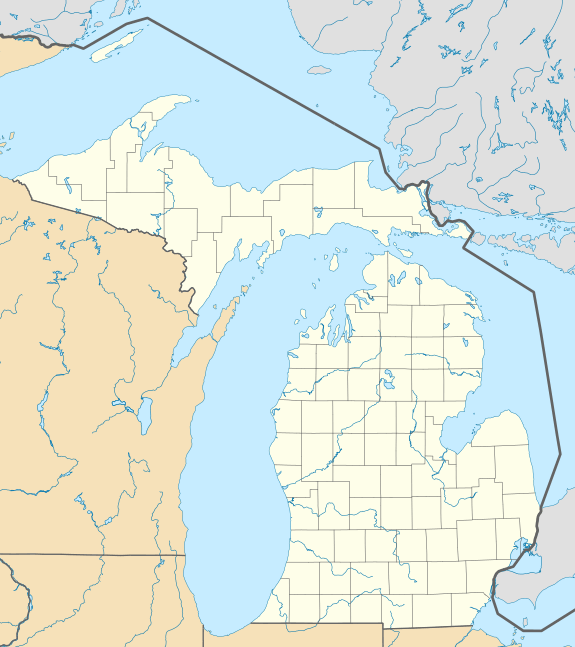

Sault Ste. Marie (/ˌsuː seɪnt məˈriː/ SOO-seint-ma-REE), officially the City of Sault Sainte Marie, is a city in, and the county seat of, Chippewa County in the U.S. state of Michigan.[5] It is on the northeastern end of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, on the Canada–US border, and separated from its twin city of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, by the St. Marys River. The city is relatively isolated from other communities in Michigan and is 346 miles via I-75 from downtown Detroit. The population was 14,144 at the 2010 census, making it the second-most populous city in the Upper Peninsula. By contrast, the Canadian Sault Ste. Marie is much larger, with more than 75,000 residents, based on more extensive industry developed in the 20th century and an economy with closer connections to other communities.

Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan | |

|---|---|

| City of Sault Sainte Marie | |

View of Sault Ste. Marie from the Canadian side of the St. Marys River | |

Flag Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Soo | |

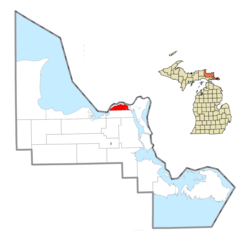

Location within Chippewa County | |

Sault Ste. Marie Location within the state of Michigan | |

| Coordinates: 46°29′49″N 84°20′44″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Chippewa |

| Founded | 1668 |

| Incorporated | 1879 (village) 1887 (city) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Don Gerrie |

| • City manager | Brian Chapman |

| Area | |

| • Total | 20.02 sq mi (51.86 km2) |

| • Land | 14.76 sq mi (38.22 km2) |

| • Water | 5.27 sq mi (13.64 km2) 26.74% |

| Elevation | 617 ft (188 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 14,144 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 13,420 |

| • Density | 923.70/sq mi (356.64/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 49783 |

| Area code(s) | 906 |

| FIPS code | 26-71740 |

| GNIS feature ID | 637276[4] |

| Website | www |

Sault Ste. Marie was settled by Native Americans more than 12,000 years ago, and was long a crossroads of fishing and trading of tribes around the Great Lakes. Beginning in the late 17th century, it developed as the first European settlement in the region that became the Midwestern United States.[6] Father Jacques Marquette, a French Jesuit, learned of the Native American village and traveled there in 1668 to found a Catholic mission. French colonists later established a fur trading post, which attracted trappers and Native Americans on a seasonal basis. By the late 18th century, both Métis men and women became active in the trade and were considered among the elite in the community. A fur-trading settlement quickly grew at the crossroads that straddled the banks of the river. It was the center of a trading route of 3,000 miles (4,800 km) that extended from Montreal to the Sault, and from the Sault to the country north of Lake Superior.[7]

For more than 140 years, the settlement was a single community under French colonial and, later British colonial rule. After the War of 1812, a US–UK Joint Boundary Commission finally fixed the border in 1817 between the Michigan Territory of the US and the British Province of Upper Canada to follow the river in this area. Whereas traders had formerly moved freely through the whole area, the United States forbade Canadian traders from operating in the United States, which reduced their trade and disrupted the area's economy. The American and Canadian communities of Sault Ste. Marie were each incorporated as independent municipalities toward the end of the nineteenth century.

Sault Sainte-Marie in French means "the Rapids of Saint Mary" (for a more detailed discussion, refer to the Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario page). The Saint Mary's River runs from Lake Superior to Lake Huron, between what are now the twin border cities on either side.

No hyphens are used in the English spelling, which is otherwise identical to the French, but the pronunciations differ. Anglophones say /ˌsuː seɪnt məˈriː/ and Francophones say [so sɛ̃t maʁi]. In French, the name can be written Sault-Sainte-Marie. On both sides of the border, the towns and the general vicinity are called The Sault (usually pronounced /suː/), or The Soo.

The two cities are joined by the International Bridge, which connects Interstate 75 (I-75) in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and Huron Street in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Shipping traffic in the Great Lakes system bypasses the rapids via the American Soo Locks, which locally is often claimed to be the world's busiest canal in terms of tonnage passing through it.

The largest ships are 1,000 feet (300 m) long by 105 feet (32 m) wide. These are domestic carriers (called lakers). Smaller recreational and tour boats use the Canadian Sault Ste. Marie Canal.

The lakers, being too large to transit the Welland Canal that bypasses Niagara Falls, are therefore land-locked. Foreign ships (termed salties) are smaller and can exit the Great Lakes to the St. Lawrence River and the Atlantic Ocean.

Sault Ste. Marie is the home of the International 500 Snowmobile Race (commonly called the I-500), which takes place annually and draws participants and spectators from all over the U.S. and Canada. The race, which was inspired by the Indianapolis 500,[8] originated in 1969 and has been growing ever since.

History

For centuries Ojibwe (Chippewa) Native Americans had lived in the area, which they referred to as Baawitigong ("at the cascading rapids"), after the rapids of St. Marys River. French colonists renamed the region Saulteaux ("rapids" in French).

In 1668, French missionaries Claude Dablon and Jacques Marquette founded a Jesuit mission at this site. Sault Ste. Marie developed as the fourth-oldest European city in the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains, and the oldest permanent settlement in contemporary Michigan state. On June 4, 1671, Simon-François Daumont de Saint-Lusson, a colonial agent, was dispatched from Quebec to the distant tribes, proposing a congress of Indian nations at the Falls of St. Mary between Lake Huron and Lake Superior. Trader Nicolas Perrot helped attract the principal chiefs, and representatives of 14 Indigenous nations were invited for the elaborate ceremony. The French officials proclaimed France's appropriation of the immense territory surrounding Lake Superior in the name of King Louis XIV.[9]

In the 18th century, the settlement became an important center of the fur trade, when it was a post for the British-owned North West Company, based in Montreal. The fur trader John Johnston, a Scots-Irish immigrant from Belfast, was considered the first European settler in 1790. He married a high-ranking Ojibwe woman named Ozhaguscodaywayquay, the daughter of a prominent chief, Waubojeeg. She also became known as Susan Johnston. Their marriage was one of many alliances in the northern areas between high-ranking European traders and Ojibwe. The family was prominent among Native Americans, First Nations, and Europeans from both Canada and the United States. They had eight children who learned fluent Ojibwe, English and French. The Johnstons entertained a variety of trappers, explorers, traders, and government officials, especially during the years before the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States.[10]

As a result of the fur trade, the settlement attracted Ojibwe and Ottawa, Métis, and ethnic Europeans of various nationalities. It was a two-tiered society, with fur traders (who had capital) and their families and upper-class Ojibwe in the upper echelon.[10] In the aftermath of the War of 1812, however, the community's society changed markedly.[10]

The U.S. built Fort Brady near the settlement, introducing new troops and settlers, mostly Anglo-American. The UK and the US settled on a new northern boundary in 1817, dividing the US and Canada along St. Mary's River. The US prohibited British fur traders from operating in the United States. After completion of the Erie Canal in New York State in 1825 (expanded in 1832), the number of settlers migrating to Ohio and Michigan increased dramatically from New York and New England, bringing with them the Yankee culture of the Northern Tier. Their numbers overwhelmed the cosmopolitan culture of the earlier settlers. They practiced more discrimination against Native Americans and Métis.

The falls proved a choke point for shipping between the Great Lakes. Early ships traveling to and from Lake Superior were portaged around the rapids[11] in a lengthy process (much like moving a house) that could take weeks. Later, only the cargoes were unloaded, hauled around the rapids, and then loaded onto other ships waiting below the rapids. The first American lock, the State Lock, was built in 1855; it was instrumental in improving shipping. The lock has been expanded and improved over the years.

In 1900, Northwestern Leather Company opened a tannery in Sault Ste. Marie.[12] The tannery was founded to process leather for the upper parts of shoes, which was finer than that for soles.[13] After the factory closed in 1958, the property was sold to Filborn Limestone, a subsidiary of Algoma Steel Corporation.[14]

In March 1938 during the Great Depression, Sophia Nolte Pullar bequeathed $70,000 for construction of the Pullar Community Building, which opened in 1939. This building held an indoor ice rink composed of artificial ice, then a revolutionary concept. The ice rink is still owned by the city.[15]

Meaning of the name

The city name was derived from the French term for the nearby rapids, which were called Les Saults de Sainte Marie. Sainte Marie (Saint Mary) was the name of the river and Saults referred to the rapids. (The archaic spelling Sault is a relic of the Middle French Period. Latin salta successively became Old French salte (c. 800 – c. 1340), Middle French sault, and Modern French saut, as in the verb sauter, to jump.)

Whereas the modern saut means simply "(a) jump", sault in the 17th century was also applied to cataracts, waterfalls and rapids. This resulted in such place names as Grand Falls/Grand-Sault, and Sault-au-Récollet on the Island of Montreal in Canada; and Sault-Saint-Remy and Sault-Brénaz in France. In contemporary French, the word for "rapids" is rapides.

Transportation

The city is the northern terminus of I-75, which connects with the Mackinac Bridge at St. Ignace 52 miles (84 km) to the south, and continues south to Miami, Florida. M-129 also has its northern terminus in the city. M-129 was at one time a part of the Dixie Highway system, which was intended to connect the northern industrial states with the southern agricultural states. Until 1984 the city was the eastern terminus of the western segment of US 2. County Highway H-63 (or Mackinac Trail) also has its northern terminus in the city and extends south to St. Ignace and follows a route very similar to I-75.

Commercial airline service is provided to the city by the Chippewa County International Airport in Kinross, about 20 miles (32 km) south of the city. Smaller general aviation aircraft also use the Sault Ste. Marie Municipal Airport about one 1 mile (1.6 km) southwest of downtown.

Sault Ste. Marie was the namesake of the Minneapolis, St. Paul and Sault Ste. Marie Railway, now the Soo Line Railroad, the U.S. arm of the Canadian Pacific Railway. This railroad had a bridge parallel to the International Bridge crossing the St. Marys River. The Soo Line has since, through a series of acquisitions and mergers of portions of the system, been split between Canadian Pacific and Canadian National Railway (CN). Canadian national operates the rail lines and the bridge in the Sault Ste. Marie area that were part of the Soo Line.

The Sugar Island Ferry provides automobile and passenger access between Sault Ste. Marie and Sugar Island, formerly a center of maple sugaring. The short route that the ferry travels crosses the shipping channel. Despite the high volume of freighter traffic through the locks, freighters typically do not dock in the Sault. However, the city hosts tugs, a tourist passenger ferry service, and a Coast Guard station along the shoreline on the lower (east) side of the Soo Locks. The United States Postal Service operates a "Marine Post Office", situated within the locks, to service ships as they pass through.

Geography and climate

The city is located at Latitude: 46.49 N, Longitude: -84.35 W.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 20.16 square miles (52.21 km2), of which 14.77 square miles (38.25 km2) is land and 5.39 square miles (13.96 km2) is water.[16] The city's downtown is on an island, formed by the Sault Ste. Marie Power Canal to the south and the St. Mary's River and Soo Locks to the north.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Sault Ste. Marie has a humid continental climate (Dfb) with cold, snowy winters and warm summers.[17] Sault Ste. Marie is one of the snowiest places in Michigan, receiving an average of 120 inches (3.0 m) of snow per winter season, with a record year when 209 inches (5.3 m) fell. 62 inches (1.6 m) of snow fell in one five-day snowstorm, including 28 inches (71 cm) in 24 hours, in December 1995.[18] Precipitation measured as equivalent rainfall, Sault Ste. Marie receives an annual average of 33 inches (840 mm). Its immediate region is the cloudiest in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, having over 200 cloudy days a year.

Temperatures in Sault Ste. Marie have varied between a record low of −36 °F (−38 °C) and a record high of 98 °F (37 °C). Monthly average temperatures range from 13 °F (−11 °C) in January to 64 °F (18 °C) in July.[19] On average, only two out of every five years reaches 90 °F (32 °C), while there are 85.5 days annually where the high remains at or below freezing and 26.5 nights with a low of 0 °F (−18 °C) or colder.

Average monthly precipitation is lowest in February, and highest in September and October. This autumn maximum in precipitation, unusual for humid continental climates, owes to this area's Great Lakes location. From May through July (usually the year's wettest months in most of the upper Midwestern United States, away from large bodies of water), the lake waters surrounding Sault Ste. Marie are cooler than nearby land areas. This tends to stabilize the atmosphere, suppressing precipitation (especially showers and thunderstorms) somewhat, in May, June and July. In autumn, the lakes are releasing their stored heat from the summer, making them warmer than the surrounding land, and increasingly frequent and strong polar and Arctic air outbreaks pick up warmth and moisture during their over-water passage, resulting in clouds and instability showers. In Sault Ste. Marie, this phenomenon peaks in September and October, making these the wettest months of the year. Also noteworthy is that in Sault Ste. Marie, the year's third wettest month, on average, is November, and not any summer month.

Satellite image from June 2007.

Satellite image from June 2007. Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan Saint Marys Falls Hydropower Plant generation station.

Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan Saint Marys Falls Hydropower Plant generation station.- Astronaut photograph of Sault Ste. Marie.

| Climate data for Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1888–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 48 (9) |

50 (10) |

83 (28) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

82 (28) |

74 (23) |

62 (17) |

98 (37) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 38.3 (3.5) |

42.5 (5.8) |

52.5 (11.4) |

70.7 (21.5) |

81.2 (27.3) |

85.1 (29.5) |

87.5 (30.8) |

85.7 (29.8) |

80.8 (27.1) |

71.1 (21.7) |

55.8 (13.2) |

43.3 (6.3) |

89.1 (31.7) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 22.7 (−5.2) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

34.4 (1.3) |

49.1 (9.5) |

62.4 (16.9) |

71.0 (21.7) |

75.9 (24.4) |

74.4 (23.6) |

66.2 (19.0) |

53.0 (11.7) |

39.9 (4.4) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

50.3 (10.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 14.7 (−9.6) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

39.6 (4.2) |

51.2 (10.7) |

59.4 (15.2) |

64.7 (18.2) |

64.0 (17.8) |

56.5 (13.6) |

45.0 (7.2) |

33.6 (0.9) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

41.1 (5.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 6.6 (−14.1) |

8.5 (−13.1) |

17.0 (−8.3) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

39.9 (4.4) |

47.8 (8.8) |

53.4 (11.9) |

53.6 (12.0) |

46.7 (8.2) |

36.9 (2.7) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −17.0 (−27.2) |

−13.4 (−25.2) |

−6.4 (−21.3) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

35.2 (1.8) |

42.2 (5.7) |

42.2 (5.7) |

32.9 (0.5) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

10.4 (−12.0) |

−8.5 (−22.5) |

−20.3 (−29.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −36 (−38) |

−37 (−38) |

−28 (−33) |

−13 (−25) |

18 (−8) |

26 (−3) |

36 (2) |

29 (−2) |

25 (−4) |

15 (−9) |

−12 (−24) |

−31 (−35) |

−37 (−38) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.18 (55) |

1.33 (34) |

1.94 (49) |

2.39 (61) |

2.57 (65) |

2.70 (69) |

2.86 (73) |

3.13 (80) |

3.81 (97) |

3.80 (97) |

3.37 (86) |

2.79 (71) |

32.88 (835) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 31.07 (78.9) |

18.57 (47.2) |

13.70 (34.8) |

6.49 (16.5) |

0.20 (0.51) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.02 (0.05) |

2.26 (5.7) |

14.99 (38.1) |

35.37 (89.8) |

124.07 (315.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in.) | 18.4 | 13.0 | 12.3 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 12.9 | 15.5 | 16.7 | 18.8 | 163.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in.) | 19.3 | 14.1 | 10.1 | 4.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 10.1 | 18.3 | 80.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.2 | 75.2 | 74.7 | 69.9 | 67.9 | 74.7 | 76.3 | 79.6 | 81.6 | 80.4 | 81.7 | 81.0 | 76.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 104.9 | 142.5 | 206.4 | 227.5 | 280.3 | 281.2 | 303.6 | 248.9 | 172.9 | 122.6 | 70.4 | 77.4 | 2,238.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 37 | 49 | 56 | 56 | 60 | 59 | 64 | 57 | 46 | 36 | 25 | 29 | 50 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[20][21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 596 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,947 | — | |

| 1890 | 5,760 | 195.8% | |

| 1900 | 10,538 | 83.0% | |

| 1910 | 12,615 | 19.7% | |

| 1920 | 12,096 | −4.1% | |

| 1930 | 13,755 | 13.7% | |

| 1940 | 15,847 | 15.2% | |

| 1950 | 17,912 | 13.0% | |

| 1960 | 18,722 | 4.5% | |

| 1970 | 15,136 | −19.2% | |

| 1980 | 14,448 | −4.5% | |

| 1990 | 14,689 | 1.7% | |

| 2000 | 14,324 | −2.5% | |

| 2010 | 14,144 | −1.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 13,420 | [3] | −5.1% |

| source:[22] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 14,144 people, 5,995 households, and 3,265 families residing in the city. The population density was 957.6 inhabitants per square mile (369.7/km2). There were 6,534 housing units at an average density of 442.4 per square mile (170.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 74.8% White, 0.7% African American, 17.7% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.3% from other races, and 5.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.5% of the population.

There were 5,995 households, of which 28.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.0% were married couples living together, 14.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 45.5% were non-families. 35.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.22 and the average family size was 2.88.

The median age in the city was 33.8 years. 21.3% of residents were under the age of 18; 17.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.8% were from 25 to 44; 23.8% were from 45 to 64; and 13.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.5% male and 51.5% female.

2000 census

| Largest ancestries (2000) [23] | Percent |

|---|---|

| German | 15% |

| Ojibwe | 14% |

| Irish | 13% |

| English | 9% |

| French | 9% |

| African American | 7% |

| Polish | 6% |

Note: After going through the Census 2000 Count Question Resolution Program, the population of the city in 2000 was revised to 14,324 because of the misallocation of some of a neighboring municipality's population to the city of Sault Ste. Marie.[24]

As of the census[25] of 2000, there were 16,542 people, 5,742 households, and 3,301 families living in the city. The population density was 1,116.3 people per square mile (431.0/km2). There were 6,237 housing units at an average density of 420.9 per square mile (162.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 73.99% White, 6.51% African American, 13.72% Native American, 0.65% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 0.47% from other races, and 4.61% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.86% of the population.

There were 5,742 households, out of which 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.9% were married couples living together, 13.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.5% were non-families. 33.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 19.4% under the age of 18, 18.1% from 18 to 24, 31.9% from 25 to 44, 18.2% from 45 to 64, and 12.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 122.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 128.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,652, and for a family was $40,333. Males had a median income of $29,656 versus $21,889 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,460. About 12.7% of families and 17.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.6% of those under age 18 and 12.5% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Tourism is a major industry in the area. The Soo Locks and nearby Kewadin Casino, Hotel and Convention Center—which is owned by the Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians—are the major draws, as well as the forests, inland lakes, and Lake Superior shoreline. Sault Ste. Marie is also a gateway to Lake Superior's scenic north shore through its twin city Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. The two cities are connected by the Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge, a steel truss arch bridge with suspended deck passing over the St. Marys River.

Education

University

Sault Ste. Marie is home to Lake Superior State University (LSSU), founded in 1946 as an extension campus of Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now Michigan Technological University); the campus was originally Fort Brady. LSSU is home to the LSSU Lakers (D1 Hockey (WCHA), D2 all other sports (GLIAC). LSSU has around 2500 students, making it Michigan's smallest public university.

High schools

The Sault's primary public high school is Sault Area High School. "Sault High" is one of the few high schools in the state with attached career center. The school's mascot is the Blue Devil. "Sault High" houses a variety of successful varsity sports teams, such as hockey, wrestling, baseball, and basketball. Altogether, the school provides 24 competitive sports teams for both boys and girls at all levels. [26]

The school district also operates Malcolm High School as an alternative high school.

Middle schools

Sault Ste. Marie has two middle schools, one in the Sault Ste. Marie School System known as Sault Area Middle School. Before the 6th grade annex was added in the late 1980s, the school was referred to as Sault Area Junior High School. The Second Middle School is a part of Joseph K. Lumsden Bahweting School, a Native American-affiliated Public School Academy.

St. Mary's Catholic School serves students in grades K–8.

Elementary school

There are two elementary schools in Sault Ste. Marie, Lincoln Elementary and Washington Elementary. There is also a Public School Academy, Joseph K. Lumsden Bahweting School, and the St. Mary's Catholic School. Jefferson Elementary, McKinley Elementary, Bruce Township Elementary, and Soo Township Elementary (converted into an Alternative High School) have closed because of declining enrollment in the school system.

Private school

- St. Mary's Catholic School

- Bahweting Native American School

Media

TV

All stations listed here are rebroadcasters of television stations based in Traverse City and Cadillac.

- Channel 8: WGTQ, ABC (rebroadcasts WGTU); NBC on digital subchannel 8.2 (rebroadcasts WPBN-TV), Comet on digital subchannel 8.3

- Channel 10: WWUP, CBS (rebroadcasts WWTV); Fox on digital subchannel 10.2 (rebroadcasts WFQX-TV), MeTV on digital subchannel 10.3

- Channel 28: W28DY-D, 3ABN (all programming via satellite)

NBC and ABC are also served by WTOM channel 4 from Cheboygan, which repeats WPBN-TV and WGTU.

The area has no local PBS, The CW, or MyNetworkTV service over-the-air. The Spectrum cable system offers all three in their regional packages through Marquette's PBS affiliate WNMU-TV, Cadillac's CW affiliate WWTV 9.4 (WWUP does not carry the subchannel), and joint MyNetworkTV/Cozi TV affiliate WXII-LP out of Cedar. Mount Pleasant PBS affiliate WCMU-TV serves the Cadillac-Traverse City market via Cadillac satellite station WCMV, but its signal does not normally reach the Sault Ste. Marie area.

None of these stations are seen on cable in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, as Shaw Cable chooses to largely air Detroit affiliates for over the air channels, while WUHF in Rochester, New York, WPIX in New York City, New York, and WSBK-TV in Boston, Massachusetts provide the closest Fox, CW, and MNTV affiliates carried by Shaw in the market.

Radio

- 1230 AM – WSOO (adult contemporary/news/sports)

- 1400 AM – WKNW (talk/sports)

- 91.5 FM – WJOH (Contemporary Christian) "Smile FM" (rebroadcasts WLGH from Lansing)

- 98.3 FM – WCMZ (NPR/jazz) (rebroadcasts WCMU-FM from Mount Pleasant)

- 99.5 FM – WYSS (contemporary hit radio)

- 101.3 FM – WSUE (active rock)

- 102.3 FM – WTHN (religious) (rebroadcasts WPHN-FM from Gaylord)

- 103.3 FM – W277AG (religious) (rebroadcasts WHWL-FM from Marquette)

Other stations serving the Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, market:

- 93.9 FM – WNBY (oldies) – Newberry, Michigan

- 95.1 FM – WUPN (classic hits) – Paradise, Michigan

- 97.9 FM – WIHC (Christian radio) – Newberry, Michigan

- 105.5 FM – WMKD (country music) – Pickford, Michigan

Print

The city's main daily paper is the Sault News formerly the Sault Evening News.

Athletics

Spectator sports in Sault Ste. Marie include Lake Superior State University Athletics and the Soo Eagles of the Northern Ontario Junior Hockey League (NOJHL). The Lakers participate in NCAA Division I Ice Hockey and Division II Women's and Men's Basketball, Women's and Men's Golf, Women's Volleyball, Women's and Men's Track and Field, Women's and Men's Tennis and Women's and Men's Cross Country.

Nicknamed the Lakers, LSSU's hockey program is celebrating its 50th season of intercollegiate competition. The team plays its home contests at Taffy Abel Arena (4,000 seats) on LSSU's campus and is one of the most decorated in NCAA hockey history. The squad claimed two NAIA titles in the 1970s before a run of three NCAA division one championships (1988, 1992, 1994) and one finalist appearance (1993) in the late 1980s and early 90s. They compete in the Western Collegiate Hockey Association (WCHA).

The rest of the athletic teams play in the Great Lakes Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (GLIAC). The basketball programs at LSSU have seen their share of success. The Men's program won overall GLIAC regular season titles in 2014–15, 2013–14, 1995-1996 (Tournament Champion) and also claimed the north division crown in 2008–09. LSSU's women's program won GLIAC gold from 2001-2002 through 2004–05. They also captured GLIAC tournament titles in 2002-03 and 2003–04. Both Men's and Women's squads play their home games in the Bud Cooper Gymnasium within the Norris Center.

Notable people

- Taffy Abel, former Olympic and NHL player

- Cliff Barton, former NHL player

- Bob Bemer, computer scientist

- Jeff Blashill, head coach of the NHL's Detroit Red Wings; born in Detroit but grew up in Sault Ste. Marie, where his father was a professor at Lake Superior State University

- Rosalynn Bliss, Mayor of Grand Rapids

- Denton G. Burdick, Oregon state legislator

- Vic Desjardins, former NHL player

- John Johnston (1762–1828), married to Ozhaguscodaywayquay (also known as Susan), daughter of Waubojeeg, an Ojibwe chief; together they built a prosperous fur trading business; among upper class in Euro-American and Ojibwe communities of region during late-18th and early-19th centuries[27]

- Lloyd H. Kincaid, former Wisconsin State Senator* Bruce Martyn, radio and TV play-by-play announcer of the Detroit Red Wings from 1964 to 1995; graduated from Lake Superior State University and began his radio career at WSOO

- Bun LaPrairie, former NHL player

- William McPherson, author and Washington Post writer, was born in Sault Ste. Marie

- Tip O'Neill, former NFL player

- Terry O'Quinn, best known for playing John Locke from the ABC show Lost, was born in Sault Ste. Marie

- Chase S. Osborn, Michigan's only Governor from the Upper Peninsula

- Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, ethnographer and U.S. Indian agent who named many counties and places in Michigan in his official capacity; husband of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft

- Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, daughter of John and Susan Johnston, recognized as the first Native American literary writer and poet, and inducted into Michigan Women's Hall of Fame in 2008

- Joseph H. Steere, Chief Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court

- Reed Timmer, American meteorologist And extreme storm chaser

- Kim A. Wilcox, Chancellor of UC Riverside

Notable landmarks

- Pullar Stadium was constructed starting in 1937 and opened in 1939. It is used as an ice arena where the Soo Eagles play.[15]

- The Ramada Plaza Hotel Ojiway opened on December 31, 1927. The first owners were Beatrice and Leon Daglman. The building is 85 years old. The 27th Governor of Michigan Chase S. Osborn donated the site and $50,000. It was his dream to build a nice elegant hotel. Overall, it cost $250,000 to build it. On the day of its opening it had 91 rooms, 33 of which included bath tubs, 13 with showers, 34 with toilet and washbowls, and 11 just had a washbowl. This hotel was made for all the tourist who came to the town. Governor Chase S. Osborn and his family lived on the sixth floor for a while and so did Beatrice and Leon Daglman. The hotel contains 100 guestrooms, dining room, checkroom, barbershop and beauty parlor. Its decorated as an Art Deco architectural design, décor, detailed amenities and exceptional service gained national interest and attracted many famous guests including Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis and more recently President George H.W. Bush in 1992[28]

- The Soo Theatre has been a part of Sault Ste. Marie for over 80 years and has provided entertainment of live plays, movies, and musicals. The Theatre opened in March 1930 and for 40 years was used for films and live performances. In May 1974 the theater was divided into red and blue cinemas, where a cement wall divided the once open auditorium. The building was then closed in 1998 and was put up for sale. In March 2003 the Soo Theatre Project Inc. purchased it for $85,000. After that the theater began restoration so plays and other types of entertainment could be put on once again.[29]

- Holy Name of Mary Pro-Cathedral (Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan) was begun by Jesuits in 1668. There are only two other parishes, one in St. Augustine, Florida and the other in Santa Fe, New Mexico, that are older in the United States.[3] On January 9, 1857 Pope Pius IX established the Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie[4] and St. Mary's was named the cathedral church for the new diocese. The present church, the fifth for the parish, was built in 1881. It was designed by Canadian architect Joseph Connolly in the Gothic Revival style. The church was extensively remodeled in three phases from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. In 1968 the parish built the Tower of History as a shrine to the Catholic missionaries who served the community.[5] It was designed to be a part of a larger complex that was to include a community center and a new church. Parish priorities changed and the structure was sold to Sault Historic Sites in 1980, who continues to operate it. Proceeds from the Tower of History still benefit the church.

- The Soo Locks are a set of parallel locks which enable ships to travel between Lake Superior and the lower Great Lakes. They are on the St. Marys River between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, between the Upper Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan and the Canadian province of Ontario. They bypass the rapids of the river, where the water falls 21 feet (7 m). The locks pass an average of 10,000 ships per year,[4] despite being closed during the winter from January through March, when ice shuts down shipping on the Great Lakes. The winter closure period is used to inspect and maintain the locks. The locks share a name (usually shortened and anglicized as Soo) with the two cities named Sault Ste. Marie, in Ontario and in Michigan, on either side of the St. Marys River. The Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge between the United States and Canada permits vehicular traffic to pass over the locks. A railroad bridge crosses the St. Marys River just upstream of the highway bridge.

- Taffy Abel Arena is the home of Lake Superior State University's Division 1 hockey team. The 4,000 seat arena is part of the Norris Center athletic complex on LSSU's campus. It was renovated in 1995 and is named after Clarence "Taffy" Abel. Abel was the first American born player to become an NHL regular and was born in the Soo.[30]

- Lake Superior State University sits on the former site of U.S. Army Fort Brady. The University has converted most of the buildings to serve housing and administrative needs for its students, faculty, guests and employees. The 115-acre campus includes several buildings which are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The University has an enrollment of around 2500 students.

Sister Cities

.svg.png)

See also

References

- "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Sault Ste. Marie". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Charter Revision Handbook (PDF). Michigan Municipal League.

- "Sault Ste. Marie – history" Archived May 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The North View, accessed December 20, 2008

- "I-500 Snowmobile Race, Sault Sainte Marie, MI". i-500.com. International 500 Snowmobile Race. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008.

- Lamontagne, Léopold (1979) [1966]. "Daumont de Saint-Lusson, Simon-François". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Bieder, Robert E. (March 1999). "Sault Ste. Marie and the War of 1812: A World Turned Upside Down in the Old Northwest". Indiana Magazine of History. 95 (1): 1–13.

- "Chapter 4: The Watery Boundary". United Divide: A Linear Portrait of the USA/Canada Border. The Center for Land Use Interpretation. Winter 2015.

- Arbic, Bernie (2003). City of the Rapids: Sault Ste. Marie’s Heritage. Allegan Forest, MI: Priscilla Press. p. 190. OCLC 603731644.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arbic (2003), p. 191.

- Arbic (2003), p. 197.

- "Pullar Community Building". City of Sault Ste. Marie. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen−Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11: 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- "Nation's snow capital: Sault Ste. Marie". Detroit News. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- "Sault Ste. Marie Climate". ClimateZone.com. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- "Sault Ste. Marie, MI Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "Sault Sainte Marie - Sault Sainte Marie - Ancestry & family history - ePodunk". www.epodunk.com. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- "Census 2000 Count Question Resolution Program – Michigan Revision Update" (PDF). Michigan Information Center. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Sault Area High School Official Page". Sault Area High School and Career Center. Archived from the original on October 24, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Margaret Noori, "Bicultural Before There Was a Word For It" Archived December 9, 2012, at Archive.today, Women's Review of Books, 2008, Wellesley Centers for Women, accessed December 12, 2008

- Nebel, Angela (December 28, 2007). Remembering the Ojibway. Sault Ste. Marie, MI: The Evening News. n.p.

- "Soo Theatre History". January 10, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- "Lake Superior State University :: James Norris Physical Education Center :: Taffy Abel Ice Arena". February 26, 2013. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- City of Sault Ste. Marie (Ontario) Archived November 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Harrison, Jim (November 30, 2013). "Imprint: My Upper Peninsula". The New York Times. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. |

- Sault Ste. Marie Visitors Bureau

- City of Sault Ste. Marie

- Tocqueville in Sault Ste. Marie – Segment from C-SPAN's Alexis de Tocqueville Tour