Portsmouth

Portsmouth (/ˈpɔːrtsməθ/ (![]()

Portsmouth City of Portsmouth | |

|---|---|

(clockwise from top:) The city viewed from Portsdown Hill, HMS Victory, Portsmouth Guildhall, Portsmouth Cathedral, the Spinnaker Tower alongside Portsmouth Harbour, Gunwharf Quays, Portchester Castle and Old Portsmouth | |

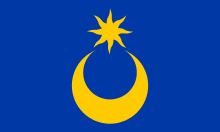

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Pompey | |

| Motto(s): Heaven's Light Our Guide | |

Location in Hampshire | |

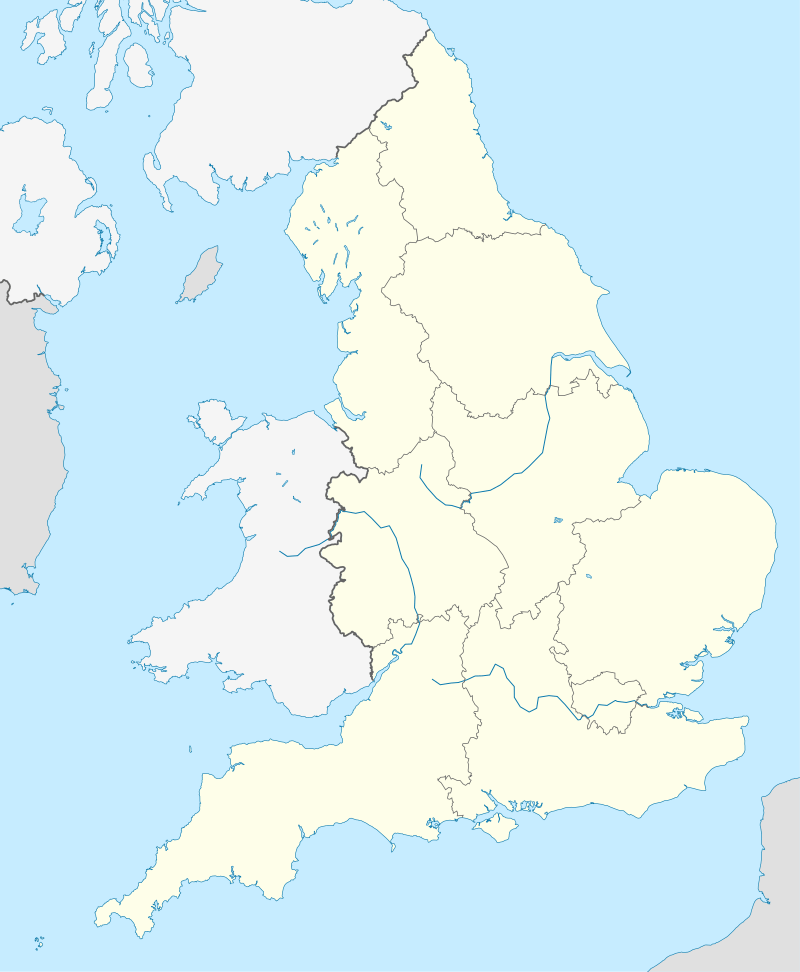

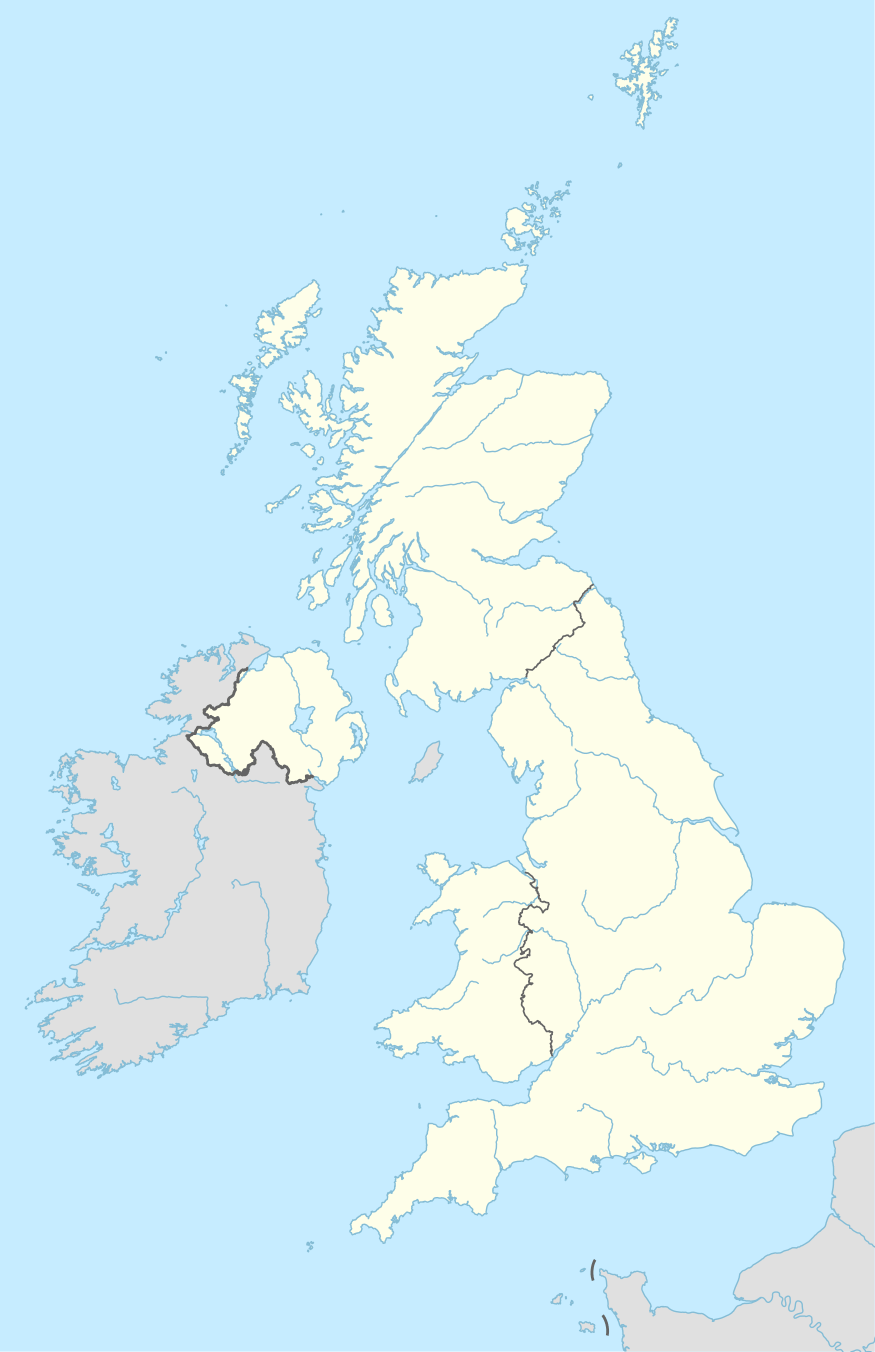

Portsmouth Location in England  Portsmouth Location in the United Kingdom  Portsmouth Location in Europe | |

| Coordinates: 50°48′21″N 01°05′14″W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | South East England |

| Ceremonial county | Hampshire |

| Admin HQ | Portsmouth city centre |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority, city |

| • Governing body | Portsmouth City Council |

| • Leadership | Leader & Cabinet |

| • Executive | Liberal Democrat (confidence and supply with Labour) |

| • MPs | Stephen Morgan (Labour) Penny Mordaunt (Conservative) |

| Area | |

| • City & unitary authority area | 15.54 sq mi (40.25 km2) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • City & unitary authority area | 238,800 (ranked 76th)[1] |

| • Urban | 855,679 |

| • Metro | 1,547,000 (2007 estimate)[2] |

| • Ethnicity (United Kingdom Census 2011 estimate)[3] | 84% White British 4.3% White Other 6.1% Asian 1.8% Black 2.7% Mixed 1.1% Other |

| Time zone | UTC0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postal code | |

| Area code(s) | 023 |

| Vehicle registration area code | HK, HL, HM, HN, HP, HR, HS, HT, HU, HV, HX, HY |

| Website | Portsmouth City Council |

Portsmouth's history can be traced back to Roman Britain. A significant naval port for centuries, it has the world's oldest dry dock. Portsmouth was England's first line of defence during the 1545 French invasion. By the early nineteenth century, the world's first mass-production line was set up in Portsmouth Dockyard's Block Mills; this made it the world's most industrialised site, and the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. Portsmouth was the most heavily-fortified town in the world and was considered "the world's greatest naval port" at the height of the British Empire, during the Pax Britannica. The Palmerston Forts were built around Portsmouth in 1859 in anticipation of another invasion from continental Europe.

King Richard I first granted Portsmouth market town status on 2 May 1194 with a royal charter and a coat of arms, "a crescent of gold on a shade of azure, with a blazing star of eight points".[5] On 21 April 1926, Portsmouth was elevated from town to city status.[6] Its motto, "Heaven's Light Our Guide" (referring to the city's eight-pointed star and crescent-moon emblem), was registered in 1929.[7] The 800th anniversary of the royal charter was celebrated on 2 May 1994.[8] Portsmouth became a unitary authority on 1 April 1997, with its city council gaining the powers of a non-metropolitan county and district council previously held by Hampshire County Council.

The city was extensively bombed in World War II's Portsmouth Blitz (which resulted in the deaths of 930 people), and was the pivotal embarkation point for the 6 June 1944 D-Day landings. In 1982, a large proportion of the task force dispatched to liberate the Falkland Islands deployed from the city's naval base. Her Majesty's Yacht Britannia left the city to oversee the 1997 transfer of Hong Kong which, for many, marked the end of the British Empire.

Portsmouth is one of the world's best-known ports; HMNB Portsmouth, considered the home of the Royal Navy, contains two-thirds of the UK's surface fleet. The city has a number of famous ships, including HMS Warrior; the Tudor carrack Mary Rose, and Horatio Nelson's flagship HMS Victory (the world's oldest naval ship still in commission). The former HMS Vernon naval-shore establishment has been redeveloped as the Gunwharf Quays retail park. Portsmouth is among the few British cities with two cathedrals: the Anglican Cathedral of St Thomas and the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St John the Evangelist. The waterfront and Portsmouth Harbour are dominated by the Spinnaker Tower, one of the United Kingdom's tallest structures at 170 metres (560 ft). Southsea is a seaside resort with an amusement arcade on Clarence Pier.

Portsmouth F.C., the city's professional football club, play their home games at Fratton Park in Milton. Portsmouth has several mainline railway stations which connect to Brighton, Cardiff, London Victoria and London Waterloo, and other lines in southern England. Portsmouth International Port is a commercial cruise-ship and ferry port for international destinations. The UK's second-busiest port (after Dover), it handles about three million passengers a year. The University of Portsmouth has a student population of 23,000. Portsmouth is the birthplace of author Charles Dickens, engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel and former Prime Minister James Callaghan.

History

Early history

The Romans built Portus Adurni, a fort, at nearby Portchester in the late third century.[9] The city's Old English name, "Portesmuða", is derived from port (a haven) and muða (the mouth of a large river or estuary).[10] In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a warrior named Port and his two sons killed a noble Briton in Portsmouth in 501.[11] Winston Churchill, in A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, wrote that Port was a pirate who founded Portsmouth in 501.[12][13]

England's southern coast was vulnerable to Danish Viking invasions during the eighth and ninth centuries, and was conquered by Danish pirates in 787.[14] In 838, during the reign of Æthelwulf, King of Wessex, a Danish fleet landed between Portsmouth and Southampton and plundered the region.[15] Æthelwulf sent Wulfherd and the governor of Dorsetshire to confront the Danes at Portsmouth, where most of their ships were docked. Although the Danes were driven off, Wulfherd was killed.[15] The Danes returned in 1001 and pillaged Portsmouth and the surrounding area, threatening the English with extinction.[16][17] They were massacred by the English survivors the following year; rebuilding began, although the town experienced further attacks until 1066.[18]

Norman to Tudor

2009.jpg)

Although Portsmouth was not mentioned in the 1086 Domesday Book, Bocheland (Buckland), Copenore (Copnor), and Frodentone (Fratton) were.[19] According to some sources, it was founded in 1180 by the Anglo-Norman merchant Jean de Gisors.[20]

King Henry II died in 1189; his son, Richard I (who had spent most of his life in France), arrived in Portsmouth en route to his coronation in London.[21] When Richard returned from captivity in Austria in May 1194, he summoned an army and a fleet of 100 ships to the port.[22] Richard gave Portsmouth market-town status with a royal charter on 2 May, authorising an annual fifteen-day free-market fair, weekly markets and a local court to deal with minor matters, and exempted its inhabitants from an £18 annual tax.[19][23] He granted the town the coat of arms of Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus, whom he had defeated during the Third Crusade in 1191: "a crescent of gold on a shade of azure, with a blazing star of eight points", reflecting significant involvement of local soldiers, sailors, and vessels in the holy war.[5] The city's 800th anniversary was celebrated in 1994.[8]

King John reaffirmed Richard I's rights and privileges, and established a permanent naval base. The first docks were begun by William of Wrotham in 1212,[19][22] and John summoned his earls, barons, and military advisers to plan an invasion of Normandy.[24] In 1229, declaring war against France, Henry III assembled a force described by historian Lake Allen as "one of the finest armies that had ever been raised in England".[25] The invasion stalled, and returned from France in October 1231.[26] Henry III summoned troops to invade Guienne in 1242, and Edward I sent supplies for his army in France in 1295.[27] Commercial interests had grown by the following century, and its exports included wool, corn, grain, and livestock.[28]

Edward II ordered all ports on the south coast to assemble their largest vessels at Portsmouth to carry soldiers and horses to the Duchy of Aquitaine in 1324 to strengthen defences.[29] A French fleet commanded by David II of Scotland attacked the English Channel, ransacked the Isle of Wight and threatened the town. Edward III instructed all maritime towns to build vessels and raise troops to rendezvous at Portsmouth.[29] Two years later, a French fleet led by Nicholas Béhuchet raided Portsmouth and destroyed most of the town; only the stone-built church and hospital survived.[30][31] After the raid, Edward III exempted the town from national taxes to aid its reconstruction.[32] Edward died in 1377; his grandson Richard II was crowned, and the French landed in Portsmouth that year. Although the town was plundered and burnt, its inhabitants drove the French off to raid towns in the West Country.[33]

Henry V built Portsmouth's first permanent fortifications. In 1416, a number of French ships blockaded the town (which housed ships which were set to invade Normandy); Henry gathered a fleet at Southampton, and invaded the Norman coast in August of that year.[34] Recognising the town's growing importance, he ordered a wooden Round Tower to be built at the mouth of the harbour; it was completed in 1426.[35] Henry VII rebuilt the fortifications with stone, assisted Robert Brygandine and Sir Reginald Bray in the construction of the world's first dry dock,[36] and raised the Square Tower in 1494.[35] He made Portsmouth a Royal Dockyard, England's only dockyard considered "national".[37] Although King Alfred may have used Portsmouth to build ships as early as the ninth century, the first warship recorded as constructed in the town was the Sweepstake (built in 1497).[38]

Henry VIII built Southsea Castle, financed by the Dissolution of the Monasteries, in 1539 in anticipation of a French invasion.[39][40] He also invested heavily in the town's dockyard, expanding it to 8 acres (3.2 ha).[41] Around this time, a Tudor defensive boom stretched from the Round Tower to Fort Blockhouse in Gosport to protect Portsmouth Harbour.[42]

From Southsea Castle, Henry witnessed his flagship Mary Rose sink in action against the French fleet in the 1545 Battle of the Solent with the loss of about 500 lives.[43] Some historians believe that the Mary Rose turned too quickly and submerged her open gun ports; according to others, it sank due to poor design.[44] Portsmouth's fortifications were improved by successive monarchs. The town experienced an outbreak of plague in 1563, which killed about 300 of its 2,000 inhabitants.[20]

Stuart to Georgian

In 1623, Charles I (then Prince of Wales) returned to Portsmouth from France and Spain.[45] His unpopular military adviser, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, was stabbed to death in an Old Portsmouth pub by war veteran John Felton five years later.[19][46] Felton never attempted to escape, and was caught walking the streets when soldiers confronted him; he said, "I know that he is dead, for I had the force of forty men when I struck the blow".[47] Felton was hanged, and his body hained to a gibbet on Southsea Common as a warning to others.[20][47] The murder took place in the Greyhound public house on High Street, which is now Buckingham House and has a commemorative plaque.[48]

Most residents (including the mayor) supported the parliamentarians during the English Civil War, although military governor Colonel Goring supported the royalists.[20] The town, a base of the parliamentarian navy, was blockaded from the sea. Parliamentarian troops were sent to besiege it, and the guns of Southsea Castle were fired at the town's royalist garrison. Parliamentarians in Gosport joined the assault, damaging St Thomas's Church.[20][49] On 5 September 1642, the remaining royalists in the garrison at the Square Tower were forced to surrender after Goring threatened to blow it up; he and his garrison were allowed safe passage.[49][50]

Under the Commonwealth of England, Robert Blake used the harbour as his base during the First Anglo-Dutch War in 1652 and the Anglo-Spanish War. He died within sight of the town, returning from Cádiz.[50] After the end of the Civil War, Portsmouth was among the first towns to declare Charles II king and began to prosper.[51] The first ship built in over 100 years, HMS Portsmouth, was launched in 1650; twelve ships were built between 1650 and 1660. After the Restoration, Charles II married Catherine of Braganza at the Royal Garrison Church.[52][53] During the late 17th century, Portsmouth continued to grow; a new wharf was constructed in 1663 for military use, and a mast pond was dug in 1665. In 1684, a list of ships docked in Portsmouth was evidence of its increasing national importance.[54] Between 1667 and 1685, the town's fortifications were rebuilt; new walls were constructed with bastions and two moats were dug, making Portsmouth one of the world's most heavily-fortified places.[20]

In 1759, General James Wolfe sailed to capture Quebec; the expedition, although successful, cost him his life. His body was brought back to Portsmouth in November, and received high naval and military honours.[55] Two years later, on 30 May 1775, Captain James Cook arrived on HMS Endeavour after circumnavigating the globe.[19][56] The 11-ship First Fleet left on 13 May 1787 to establish the first European colony in Australia, the beginning of prisoner transportation;[57][58] Captain William Bligh of HMS Bounty also sailed from the harbour that year.[19][59] After the 28 April 1789 mutiny on the Bounty, HMS Pandora was dispatched from Portsmouth to bring the mutineers back for trial. The court-martial opened on 12 September 1792 aboard HMS Duke in Portsmouth Harbour; of the ten remaining men, three were sentenced to death.[60][61] In 1789, a chapel was erected in Prince George's Street and was dedicated to St John by the Bishop of Winchester. Around this time, a bill was passed in the House of Commons on the creation of a canal to link Portsmouth to Chichester; however, the project was abandoned.[62]

The city's nickname, Pompey, is thought to have derived from the log entry of Portsmouth Point (contracted "Po'm.P." – Po'rtsmouth P.oint) as ships entered the harbour; navigational charts use the contraction.[63] According to one historian, the name may have been brought back from a group of Portsmouth-based sailors who visited Pompey's Pillar in Alexandria, Egypt, around 1781.[64] Another theory is that it is named after the harbour's guardship, Pompee, a 74-gun French ship of the line captured in 1793.[65]

Portsmouth's coat of arms is attested in the early 19th century as "azure a crescent or, surmounted by an estoile of eight points of the last."[66] Its design is apparently based on 18th-century mayoral seals.[67] A connection of the coat of arms with the Great Seal of Richard I (which had a separate star and crescent) dates to the 20th century.[68]

Industrial Revolution to Victorian

Marc Isambard Brunel established the world's first mass-production line at Portsmouth Block Mills, making pulley blocks for rigging on the navy's ships.[69] The first machines were installed in January 1803, and the final set (for large blocks) in March 1805. In 1808, the mills produced 130,000 blocks.[70] By the turn of the 19th century, Portsmouth was the largest industrial site in the world; it had a workforce of 8,000, and an annual budget of £570,000.[71]

In 1805, Admiral Nelson left Portsmouth to command the fleet which defeated France and Spain at the Battle of Trafalgar.[19] Before departing, Nelson told the crew of HMS Victory and workers in the dockyard that "England expects every man will do his duty".[72] The Royal Navy's reliance on Portsmouth led to its becoming the most fortified city in the world.[73] A network of forts, known as the Palmerston Forts, was built around the town as part of a programme led by Prime Minister Lord Palmerston to defend British military bases from an inland attack. The forts were nicknamed "Palmerston's Follies" because their armaments were pointed inland and not out to sea.[74] The Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron, tasked with halting the slave trade, began operating out of Portsmouth in 1808.[75]

In April 1811, the Portsea Island Company constructed the first piped-water supply[76] to upper- and middle-class houses.[20] It supplied water to about 4,500 of Portsmouth's 14,000 houses, generating an income of £5,000 a year.[76] HMS Victory's active career ended in 1812, when she was moored in Portsmouth Harbour and used as a depot ship. The town of Gosport contributed £75 a year to the ship's maintenance.[72] In 1818, John Pounds began teaching working-class children in the country's first ragged school.[77][78] The Portsea Improvement Commissioners installed gas street lighting throughout Portsmouth in 1820,[19] followed by Old Portsmouth three years later.[20]

During the 19th century, Portsmouth expanded across Portsea Island. Buckland was merged into the town by the 1860s, and Fratton and Stamshaw were incorporated by the next decade. Between 1865 and 1870, the council built sewers after more than 800 people died in a cholera epidemic; according to a by-law, any house within 100 feet (30 m) of a sewer had to be connected to it.[19] By 1871 the population had risen to 100,000,[20] and the national census listed Portsmouth's population as 113,569.[19] A working-class suburb was constructed in the 1870s, when about 1,820 houses were built, and it became Somerstown.[19] Despite public-health improvements, 514 people died in an 1872 smallpox epidemic.[19] On 21 December of that year, the Challenger expedition embarked on a 68,890-nautical-mile (127,580 km) circumnavigation of the globe for scientific research.[79][80]

Edwardian to Second World War

When the British Empire was at its height of power, covering a quarter of Earth's total land area and 458 million people at the turn of the 20th century, Portsmouth was considered "the world's greatest naval port".[81] In 1900, Portsmouth Dockyard employed 8,000 people – a figure which increased to 23,000 during the First World War.[20][82] On 1 October 1916, Portsmouth was bombed by a Zeppelin airship.[83] Although the Oberste Heeresleitung (German Supreme Army Command) said that the town was "lavishly bombarded with good results", there were no reports of bombs dropped in the area.[84] According to another source, the bombs were mistakenly dropped into the harbour rather than the dockyard.[83] About 1,200 ships were refitted in the dockyard during the war, making it one of the empire's most strategic ports at the time.[82]

Portsmouth was granted city status in 1926 after a long campaign by the borough council. The application was made on the grounds that it was the "first naval port of the kingdom".[85] In 1929, the city council added the motto "Heaven's Light Our Guide" to the medieval coat of arms. Except for the celestial objects in the arms, the motto was that of the Star of India and referred to the troopships bound for British India which left from the port.[86] The crest and supporters are based on those of the royal arms, but altered to show the city's maritime connections: the lions and unicorn have fish tails, and a naval crown and a representation of the Tudor defensive boom which stretched across Portsmouth Harbour are around the unicorn.[86][42]

During the Second World War, the city (particularly the port) was bombed extensively by the Luftwaffe in the Portsmouth Blitz.[19] Portsmouth experienced 67 air raids between July 1940 and May 1944, which destroyed 6,625 houses and severely damaged 6,549.[20] The air raids caused 930 deaths and wounded almost 3,000 people,[87][88] many in the dockyard and military establishments.[89] On the night of the city's heaviest raid (10 January 1941), the Luftwaffe dropped 140 tonnes of high-explosive bombs which killed 171 people and left 3,000 homeless.[90] Many of the city's houses were damaged, and areas of Landport and Old Portsmouth destroyed; the future site of Gunwharf Quays was razed to the ground.[91] The Guildhall was hit by an incendiary bomb which burnt out the interior and destroyed its inner walls,[92] although the civic plate was retrieved unharmed from the vault under the front steps.[87] After the raid, Portsmouth mayor Denis Daley wrote for the Evening News:

We are bruised but we are not daunted, and we are still as determined as ever to stand side by side with other cities who have felt the blast of the enemy, and we shall, with them, persevere with an unflagging spirit towards a conclusive and decisive victory.

— Sir Denis Daley, January 1941[93]

Portsmouth Harbour was a vital military embarkation point for the 6 June 1944 D-Day landings. Southwick House, just north of the city, was the headquarters of Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower.[94][95] A V-1 flying bomb hit Newcomen Road on 15 July 1944, killing 15 people.[20]

1945 to present

Much of the city's housing stock was damaged during the war. The wreckage was cleared in an attempt to improve housing quality after the war; before permanent accommodations could be built, Portsmouth City Council built prefabs for those who had lost their homes. More than 700 prefab houses were constructed between 1945 and 1947, some over bomb sites.[20] The first permanent houses were built away from the city centre, in new developments such as Paulsgrove and Leigh Park;[96][97] construction of council estates in Paulsgrove was completed in 1953. The first Leigh Park housing estates were completed in 1949, although construction in the area continued until 1974.[20] Builders still occasionally find unexploded bombs, such as on the site of the destroyed Hippodrome Theatre in 1984.[98] Despite efforts by the city council to build new housing, a 1955 survey indicated that 7,000 houses in Portsmouth were unfit for human habitation. A controversial decision was made to replace a section of the central city, including Landport, Somerstown and Buckland, with council housing during the 1960s and early 1970s. The success of the project and the quality of its housing are debatable.[20]

Portsmouth was affected by the decline of the British Empire in the second half of the 20th century. Shipbuilding jobs fell from 46 percent of the workforce in 1951 to 14 percent in 1966, drastically reducing manpower in the dockyard. The city council attempted to create new work; an industrial estate was built in Fratton in 1948, and others were built at Paulsgrove and Farlington during the 1950s and 1960s.[20] Although traditional industries such as brewing and corset manufacturing disappeared during this time, electrical engineering became a major employer. Despite the cutbacks in traditional sectors, Portsmouth remained attractive to industry. Zurich Insurance Group moved their UK headquarters to the city in 1968, and IBM relocating their European headquarters in 1979.[20] Portsmouth's population had dropped from about 200,000 to 177,142 by the end of the 1960s.[99] Defence Secretary John Nott decided in the early 1980s that of the four home dockyards, Portsmouth and Chatham would be closed. The city council won a concession, however, and the dockyard was downgraded instead to a naval base.[100]

On 2 April 1982, Argentine forces invaded two British territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The British government's response was to dispatch a naval task force, and the aircraft carriers HMS Hermes and HMS Invincible sailed from Portsmouth for the South Atlantic on 5 April. The successful outcome of the war reaffirmed Portsmouth's significance as a naval port and its importance to the defence of British interests.[101] In January 1997, Her Majesty's Yacht Britannia embarked from the city on her final voyage to oversee the handover of Hong Kong; for many, this marked the end of the empire.[102][103] She was decommissioned on 11 December of that year at Portsmouth Naval Base in the presence of the queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, and twelve senior members of the royal family.[104][105]

Redevelopment of the naval shore establishment HMS Vernon began in 2001 as a complex of retail outlets, clubs, pubs, and a shopping centre known as Gunwharf Quays.[20] Construction of the 552-foot-tall (168 m) Spinnaker Tower, sponsored by the National Lottery, began at Gunwharf Quays in 2003.[106] The Tricorn Centre, called "the ugliest building in the UK" by the BBC, was demolished in late 2004 after years of debate over the expense of demolition and whether it was worth preserving as an example of 1960s brutalist architecture.[107][108] Designed by Owen Luder as part of a project to "revitalise" Portsmouth in the 1960s, it consisted of a shopping centre, market, nightclubs, and a multistorey car park.[109] Portsmouth celebrated the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar in 2005, with Queen Elizabeth II present at a fleet review and a mock battle.[20] The naval base is home to two-thirds of Britain's surface fleet.[110]

Geography

Portsmouth is 73.5 miles (118.3 km) by road from central London, 49.5 miles (79.7 km) west of Brighton, and 22.3 miles (35.9 km) east of Southampton.[111] It is located primarily on Portsea Island and is the United Kingdom's only island city, although the city has expanded to the mainland.[112] Gosport is a borough to the west.[111] Portsea Island s separated from the mainland by Portsbridge Creek,[113] which is crossed by three road bridges (the M275 motorway, the A3 road, and the A2030 road), a railway bridge, and two footbridges.[114] Portsea Island, part of the Hampshire Basin,[115] is low-lying; most of the island is less than 3 metres (9.8 ft) above sea level.[116][117] The island's highest natural elevation is the Kingston Cross road junction, at 21 feet (6.4 m) above ordinary spring tide.[118]

Old Portsmouth, the city's oldest part, is in the south-west part of the island and includes Portsmouth Point (nicknamed Spice Island).[119] The main channel entering Portsmouth Harbour, west of the island,[113] passes between Old Portsmouth and Gosport.[111] Portsmouth Harbour has a series of lakes, including Fountain Lake (near the harbour), Portchester Lake (south central), Brick Kiln Lake and Tipner (east), and Bombketch and Spider Lakes (west). Further northwest, around Portchester, are Wicor, Cams, and Great Cams Lakes.[111] The large tidal inlet of Langstone Harbour is east of the island. The Farlington Marshes, in the north off the coast of Farlington, is a 125-hectare (308-acre) grazing marsh and saline lagoon. One of the oldest local reserves in the county, built from reclaimed land in 1771, it provides habitat for migratory wildfowl and waders.[120]

South of Portsmouth are Spithead, the Solent, and the Isle of Wight. Its southern coast was fortified by the Round Tower, the Square Tower, Southsea Castle, Lumps Fort and Fort Cumberland.[121] Four sea forts were built in the Solent by Lord Palmerston: Spitbank Fort, St Helens Fort, Horse Sand Fort and No Man's Land Fort.

The resort of Southsea is south of the island,[122] and Eastney is east.[123] Eastney Lake covered nearly 170 acres (69 hectares) in 1626.[124] North of Eastney is the residential Milton and an area of reclaimed land known as Milton Common (formerly Milton Lake),[111] a "flat scrubby land with a series of freshwater lakes".[125] Further north on the east coast is Baffins, with the Great Salterns recreation ground and golf course around Portsmouth College.[111]

The Hilsea Lines are a series of defunct fortifications on the island's north coast, bordering Portsbridge Creek and the mainland.[126][127] Portsdown Hill dominates the skyline in the north, and contains several large Palmerston Forts[lower-alpha 1] such as Fort Fareham, Fort Wallington, Fort Nelson, Fort Southwick, Fort Widley, and Fort Purbrook.[121][128] Portsdown Hill is a large band of chalk; the rest of Portsea Island is composed of layers of London Clay and sand (part of the Bagshot Formation), formed principally during the Eocene.[129]

Northern areas of the city include Stamshaw, Hilsea and Copnor, Cosham, Drayton, Farlington, and Port Solent.[130] Other districts include North End and Fratton.[131][132] The west of the city contains council estates, such as Buckland, Landport, and Portsea, which replaced Victorian terraces destroyed by Second World War bombing.[20] After the war, the 2,000-acre (810 ha) Leigh Park estate was built to address the chronic housing shortage during post-war reconstruction.[96] Although the estate has been under the jurisdiction of Havant Borough Council since the early 2000s, Portsmouth City Council remains its landlord (the borough's largest landowner).[97]

The city's main station, Portsmouth and Southsea railway station,[133] is in the city centre near the Guildhall and the civic offices.[87][134] South of the Guildhall is Guildhall Walk, with a number of pubs and clubs.[135] Edinburgh Road contains the city's Roman Catholic cathedral and Victoria Park, a 15-acre (6.1 ha) park which opened in 1878.[136]

Climate

Portsmouth has a mild oceanic climate, with more sunshine than most of the British Isles.[137] Frosts are light and short-lived and snow quite rare in winter, with temperatures rarely dropping below freezing.[116] The average maximum temperature in January is 10 °C (50 °F), and the average minimum is 5 °C (41 °F). The lowest recorded temperature is −8 °C (18 °F).[138] In summer, temperatures sometimes reach 30 °C (86 °F). The average maximum temperature in July is 22 °C (72 °F), and the average minimum is 15 °C (59 °F). The highest recorded temperature is 35 °C (95 °F).[138] The city gets about 645 millimetres (25.4 in) of rain annually, with a minimum of 1 mm (0.04 in) of rain reported 103 days per year.[139]

| Climate data for Solent MRSC weather station, Lee-on-Solent, elevation: 9 metres (30 feet) (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 68.8 (2.71) |

49.3 (1.94) |

51.6 (2.03) |

42.4 (1.67) |

43.4 (1.71) |

42.0 (1.65) |

44.5 (1.75) |

50.0 (1.97) |

53.7 (2.11) |

86.2 (3.39) |

83.2 (3.28) |

83.9 (3.30) |

699.1 (27.52) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.6 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 8.7 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 12.2 | 108.6 |

| Source: Met Office[140] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Southsea, Portsmouth 1976–2005 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.9 (58.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.2 (48.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65 (2.6) |

50 (2.0) |

52 (2.0) |

42 (1.7) |

28 (1.1) |

40 (1.6) |

32 (1.3) |

43 (1.7) |

62 (2.4) |

81 (3.2) |

72 (2.8) |

80 (3.1) |

647 (25.5) |

| Average rainy days | 11.2 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 8.5 | 10.9 | 10.3 | 11.2 | 103.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 67.9 | 89.6 | 132.7 | 200.5 | 240.8 | 247.6 | 261.8 | 240.7 | 172.9 | 121.8 | 82.3 | 60.5 | 1,919.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 26 | 31 | 36 | 49 | 51 | 51 | 54 | 54 | 46 | 38 | 31 | 25 | 41 |

| Source 1: [139] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: BADC[141] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.5 °C (49.1 °F) | 9.0 °C (48.2 °F) | 8.6 °C (47.5 °F) | 9.8 °C (49.6 °F) | 11.4 °C (52.5 °F) | 13.5 °C (56.3 °F) | 15.3 °C (59.5 °F) | 16.8 °C (62.2 °F) | 17.3 °C (63.1 °F) | 16.2 °C (61.2 °F) | 14.4 °C (57.9 °F) | 11.8 °C (53.2 °F) | 12.8 °C (55.0 °F) |

Demographics

Portsmouth is the only city in the United Kingdom whose population density exceeds that of London.[143][144][145][146] In the 2011 census, the city had 205,400 residents[143][147] a population density of 5,100 per square kilometre (0.4 sq. mi.): eleven times the regional average of 440 per square kilometre and more than London, which has 4,900 people per square kilometre. The city was more densely populated, with the 1951 census showing a population of 233,545.[148][149] In a reversal of that decrease, its population has been gradually increasing since the 1990s.[150] With about 860,000 residents, South Hampshire is the fifth-largest urban area in England and the largest in South East England; it is the centre of one of the United Kingdom's most-populous metropolitan areas.[151]

The city is predominantly white (91.8 percent of the population).[152] However, Portsmouth's long association with the Royal Navy ensures some diversity.[153] Some large, well-established non-white communities have their roots in the Royal Navy, particularly the Chinese community from British Hong Kong.[153][154] Portsmouth's long industrial history with the Royal Navy has drawn many people from across the British Isles (particularly Irish Catholics) to its factories and docks.[155][lower-alpha 2] According to the 2011 census, Portsmouth's population was 84 percent White British, 3.8 percent other White, 1.3 percent Chinese, 1.4 percent Indian, 0.5 percent mixed race, 1.8 percent Bangladeshi, 0.5 percent other, 1.4 percent Black African, 0.5 percent white Irish, 1.3 percent other Asian, 0.3 percent Pakistani, 0.3 percent Black Caribbean and 0.1 percent other Black.[1][158]

| Population growth in Portsmouth since 1310[159] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1310 | 1560 | 1801 | 1851 | 1901 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | |||||||||||

| Population | 740 (est) | 1000 (est) | 32,160 | 72,096 | 188,133 | 233,545 | 215,077 | 197,431 | 175,382 | 177,142 | 186,700 | 205,400 | |||||||||||

Government and politics

The city is administered by Portsmouth City Council, a unitary authority which is responsible for local affairs. Portsmouth was granted its first charter in 1194.[160] In the early 20th century, its boundaries were extended to all of Portsea Island; they were further extended in 1920 and 1932, including areas of the mainland and adjacent villages such as Drayton and Farlington.[20][161] On 1 April 1974, it formed the second tier of local government (below Hampshire County Council);[162] Portsmouth and Southampton became administratively independent of Hampshire with the creation of the unitary authority on 1 April 1997.[163] The city is divided into two parliamentary constituencies, Portsmouth South and Portsmouth North, represented in the House of Commons by Stephen Morgan of the Labour Party and Penny Mordaunt of the Conservative Party.[164]

The city council has 42 councillors. After the May 2018 local elections, the Liberal Democrats formed a minority administration (16 councillors) supported by Labour (five councillors). The Conservatives have 19, including lord mayor Lee Mason.[165] Two councillors are independent. Councillors are returned from 14 wards; each ward has three councillors,[165] who serve four-year terms.[166] The leader of the council is the Liberal Democrat, Gerald Vernon-Jackson. The lord mayor usually has a one-year term.[167]

The council is based in the civic offices, which house the tax-support, housing-benefits, resident-services, and municipal-functions departments.[168] They are in Guildhall Square, with the Portsmouth Guildhall and Portsmouth Central Library. The Guildhall, a symbol of Portsmouth, is a cultural venue. It was designed by Leeds-based architect William Hill, who began it in the neo-classical style in 1873 at a cost of £140,000.[93][169] It was opened to the public in 1890.[170]

Economy

Ten percent of Portsmouth's workforce is employed at Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, which is linked to the city's biggest industry, defence; the headquarters of BAE Systems Surface Ships is in the city.[171] BAE's Portsmouth shipyard received construction work on the two new Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers.[172][173][174] A £100 million contract was signed to develop needed facilities for the vessels.[174] A ferry port handles passengers and cargo,[175] and a fishing fleet of 20 to 30 boats operates out of Camber Quay, Old Portsmouth; most of the catch is sold at the quayside fish market.[176]

The city is host to the of IBM's European headquarters is in Portsmouth, the UK headquarters of Zurich Financial Services until 2007.[20][177] City shopping is centred on Commercial Road and the 1980s Cascades Shopping Centre.[178][179] The shopping centre has 185,000 to 230,000 visitors weekly.[180] Redevelopment has created new shopping areas, including the Gunwharf Quays (the repurposed HMS Vernon shore establishment,[181][182] with stores, restaurants and a cinema) and the Historic Dockyard, which caters to tourists and holds an annual Victorian Christmas market.[183][184] Ocean Retail Park, on the north-eastern side of Portsea Island, was built in September 1985 on the site of a former metal-box factory.[185]

Development of Gunwharf Quays continued until 2007, when the 330-foot-tall (101 m) No. 1 Gunwharf Quays residential tower was completed.[186][187] The development of the former Brickwoods Brewery site included the construction of the 22-storey Admiralty Quarter Tower, the tallest in a complex of primarily low-rise residential buildings.[188] Number One Portsmouth, a proposed 25-storey 330 feet (101 m) tower opposite Portsmouth & Southsea station, was announced at the end of October 2008.[189] In August 2009, internal demolition of the existing building had begun.[190] A high-rise student dormitory, nicknamed "The Blade", has begun construction on the site of the swimming baths at the edge of Victoria Park. The 300-foot (91 m) tower will be Portsmouth's second-tallest structure, after the Spinnaker Tower.[191]

In April 2007, Portsmouth F.C. announced plans to move from Fratton Park to a new stadium on reclaimed land next to the Historic Dockyard. The £600 million mixed-use development, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, would include shops, offices and 1,500 harbourside apartments.[192][193] The scheme was criticised for its size and location, and some officials said that it would interfere with harbour operations.[194][195] The project was rejected by the city council due to the 2008 financial crisis.[196]

Portsmouth's two Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales, were ordered by defence secretary Des Browne on 25 July 2007.[197] They were built in the Firth of Forth at Rosyth Dockyard and BAE Systems Surface Ships in Glasgow, Babcock International at Rosyth, and at HMNB Portsmouth.[198][199] The government announced before the 2014 Scottish independence referendum that military shipbuilding would end in Portsmouth, with all UK surface-warship construction focused on the two older BAE facilities in Glasgow.[200] The announcement was criticised as a political decision to aid the referendum's "No" campaign.[201][202]

Culture

Portsmouth has several theatres. The New Theatre Royal in Guildhall Walk, near the city centre, specialises in professional drama.[203] The restored Kings Theatre in Southsea features amateur musicals and national tours.[204] The Groundlings Theatre, built in 1784, is housed at the Old Beneficial School in Portsea.[205] New Prince's Theatre and Southsea's Kings Theatre were designed by Victorian architect Frank Matcham.[206]

The city has three musical venues: the Guildhall,[207] the Wedgewood Rooms (which includes Edge of the Wedge, a smaller venue),[208] and Portsmouth Pyramids Centre.[209] Portsmouth Guildhall is one of the largest venues in South East England, with a seating capacity of 2,500.[87][210][211] A concert series is presented at the Guildhall by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra.[212] The Portsmouth Sinfonia approached classical music from a different angle during the 1970s, recruiting players with no musical training or who played an instrument new to them.[213][214] The Portsmouth Summer Show is held at King George's Fields. The 2016 show held during the last weekend of April, featured cover bands such as the Silver Beatles, the Bog Rolling Stones, and Fleetingwood Mac.[215]

A number of musical works are set in the city. Portsmouth Point is a 1925 overture for orchestra by English composer William Walton, inspired by Thomas Rowlandson's etching of Portsmouth Point in Old Portsmouth.[216][217] The overture was played during a 2007 BBC Proms concert.[218] H.M.S. Pinafore is a comic opera in two acts set in Portsmouth Harbour, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert.[219] John Cranko's 1951 ballet Pineapple Poll, which features music from Gilbert and Sullivan's operetta The Bumboat Woman's Story, is also set in Portsmouth.[220][221]

Portsmouth hosts yearly remembrances of the D-Day landings, attended by veterans from Allied and Commonwealth nations.[222][223] The city played a major role in the 50th D-Day anniversary in 1994; visitors included US President Bill Clinton, Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating, King Harald V of Norway, French President François Mitterrand, New Zealand Prime Minister Jim Bolger, Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, Prime Minister John Major, the Queen, and the Duke of Edinburgh.[224][225] The 75th Anniversary of D-Day was similarly commemorated in the city. Prime Minister Theresa May led the event, and was joined by leaders of the US, Canada, Australia, France and Germany.[226]

The annual Portsmouth International Kite Festival, organised by the city council and the Kite Society of Great Britain, celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2016.[227]

Literature

Portsmouth, inhabited largely by incestuous and necrophiliac criminals, is the main setting of Jonathan Meades' 1993 novel Pompey.[228] Since the novel was published, Meades has presented a TV programme documenting Victorian architecture in Portsmouth Dockyard.[229] Portsmouth is the hometown of Fanny Price, the main character of Jane Austen's novel Mansfield Park, and most of its closing chapters are set there.[230] Nicholas and Smike, the main protagonists of Charles Dickens' novel The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, make their way to Portsmouth and become involved with a theatrical troupe.[231] Portsmouth is most often the port from which Captain Jack Aubrey's ships sail in Patrick O'Brian's seafaring historical Aubrey-Maturin series.[232]

Victorian novelist and historian Sir Walter Besant documented his 1840s childhood in By Celia's Arbour: A Tale of Portsmouth Town, precisely describing the town before its defensive walls were removed.[233] Southsea (as Port Burdock) features in The History of Mr Polly by H. G. Wells, who describes it as "one of the three townships that are grouped around the Port Burdock naval dockyards".[234] The resort is also the setting of the graphic novel The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch by high fantasy author Neil Gaiman, who grew up in Portsmouth. A Southsea street was renamed The Ocean at the End of the Lane by the city council in honour of Gaiman's novel of the same name.[235][236]

Crime novels set in Portsmouth and the surrounding area include Graham Hurley's D.I. Faraday/D.C. Winter novels[237] and C. J. Sansom's Tudor crime novel, Heartstone; the latter refers to the warship Mary Rose and describes Tudor life in the town.[238] Portsmouth Fairy Tales for Grown Ups, a collection of short stories, was published in 2014.[239][240] The collection, set around Portsmouth, includes stories by crime novelists William Sutton and Diana Bretherick.[241][242]

Education

The University of Portsmouth was founded in 1992 as a new university from Portsmouth Polytechnic; in 2016, it had 20,000 students.[243] The university was ranked among the world's top 100 modern universities in April 2015.[244][245] In 2013, it had about 23,000 students and over 2,500 staff members.[246] Several local colleges also award Higher National Diplomas, including Highbury College (specialising in vocational education),[247] and Portsmouth College (which offers academic courses).[248] Admiral Lord Nelson School and Miltoncross Academy were built in the late 1990s to meet the needs of a growing school-age population.[249][250]

After the cancellation of the national building programme for schools, redevelopment halted.[251] Two schools in the city were judged "inadequate", and 29 of its 63 schools were considered "no longer good enough" by Ofsted in 2009.[252] Before it was taken over by Ark Schools and became a Charter Academy, St Luke's Church of England secondary school was one of England's worst schools in GCSE achievement. It was criticised by officials for its behavioural standards, with students reportedly throwing chairs at teachers.[253] Since it became an academy in 2009, the school has improved; 69 percent of its students achieved five GCSEs with grades of A* to C, including English and mathematics.[254] The academy's intake policy is for a standard comprehensive school, drawing from the community rather than by religion.[255]

Portsmouth Grammar School, the city's oldest independent school (founded in 1732),[256][257] has been rated one of England's best private schools.[258][257] Portsmouth High School, a member of the Girls Day School Trust, was ranked one of the UK's top private girls' schools by A-level results in 2013.[259] Other independent schools nclude Mayville High School (founded in 1897),[260] and St John's College, a Catholic boarding school.[261][262]

Landmarks

Many of Portsmouth's former defences are now museums or event venues. Several Victorian-era forts on Portsdown Hill are tourist attractions;[263] Fort Nelson, a its summit, is home to the Royal Armouries museum.[264] Tudor-era Southsea Castle has a small museum, and much of the seafront defences leading to the Round Tower are open to the public. The castle was withdrawn from active service in 1960, and was purchased by Portsmouth City Council.[265] The southern part of the Royal Marines' Eastney Barracks is now the Royal Marines Museum, and was opened to the public under the National Heritage Act 1983.[266] The museum received a £14 million grant from the National Lottery Fund, and was scheduled to relocate to Portsmouth Historic Dockyard in 2019.[267] The birthplace of Charles Dickens, at Mile End Terrace,[268][269] is the Charles Dickens' Birthplace Museum; the four-storey red brick building became a Grade I listed building in 1953.[270] Other tourist attractions include the Blue Reef Aquarium (with an "underwater safari" of British aquatic life)[271] and the Cumberland House Natural History Museum, housing a variety of local wildlife.[272][273]

Most of the city's landmarks and tourist attractions are related to its naval history. They include the D-Day Story in Southsea, which contains the 83-metre-long (272 ft) Overlord Embroidery.[274][275] Portsmouth is home to several well-known ships; Horatio Nelson's flagship HMS Victory, the world's oldest naval ship still in commission, is in the dry dock of Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. The Victory was placed in permanent dry dock in 1922 when the Society for Nautical Research led a national appeal to restore her,[72] and 22 million people have visited the ship.[276] The remains of Henry VIII's flagship, Mary Rose, was rediscovered on the seabed in 1971.[44] She was raised and brought to a purpose-built structure in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard in 1982.[277] Britain's first iron-hulled warship, HMS Warrior, was restored and moved to Portsmouth in June 1987 after serving as an oil fuel pier at Pembroke Dock in Pembrokeshire for fifty years.[278][279][280] The National Museum of the Royal Navy, in the dockyard, is sponsored by an charity which promotes research of the Royal Dockyard's history and archaeology.[281] The dockyard hosts the Victorian Festival of Christmas, featuring Father Christmas in a traditional green robe, each November.[282][283]

Portsmouth's long association with the armed forces is demonstrated by a large number of war memorials, including several at the Royal Marines Museum[284] and a large collection of memorials related to the Royal Navy in Victoria Park.[136] The Portsmouth Naval Memorial, in Southsea Common, commemorates the 24,591 British soldiers who died during the First World War.[285] Designed by Sir Robert Lorimer, it was unveiled by George VI on 15 October 1924.[286] In the city centre, the Guildhall Square Cenotaph contains the names of the fallen and is guarded by stone sculptures of machine gunners by Charles Sargeant Jagger.[287] The west face of the memorial reads:

This memorial was erected by the people of Portsmouth in proud and loving memory of those who in the glorious morning of their days for England's sake lost all but England's praise. May light perpetual shine upon them.[288]

The city has three cemeteries: Kingston, Milton Road, and Highland Road. Kingston Cemetery, opened in 1856, is in east Fratton. At 52 acres (21 ha), it is Portsmouth's largest cemetery and has about 400 burials a year.[289] In February 2014, a ceremony celebrating the 180th anniversary of Portsmouth's Polish community was held at the cemetery.[290] The approximately 25-acre (10 ha) Milton Road Cemetery, founded on 8 April 1912, has about 200 burials per year. There is a crematorium in Portchester.[289]

Gunwharf Quays

The naval shore establishment HMS Vernon contained the Royal Navy's arsenal; weapons and ammunition would be taken from ships as they entered the harbour, and resupplied when they headed back to sea. The 1919 Southsea and Portsmouth Official Guide described the establishment as "the finest collections of weapons outside the Tower of London, containing more than 25,000 rifles".[291] During the early nineteenth century, Gunwharf Quays supplied the fleet with a "grand arsenal" of cannons, mortars, bombs, and ordnance. Although gunpowder was not provided due to safety concerns, it could be obtained at Pridday's Hard (near Gosport).[292] An armoury sold small arms to soldiers, and the stone frigate also had blacksmith and carpenter shops for armourers. It was run by three officers: a viz (storekeeper), a clerk, and a foreman. By 1817, Gunwharf reportedly employed 5,000 men and housed the world's largest naval arsenal.[293]

The Vernon closed on 1 April 1996[294] and was redeveloped by Portsmouth City Council as Gunwharf Quays,[181] a mixed residential and retail site with outlet stores, restaurants, pubs, and cafés.[295] Construction of the Spinnaker Tower began in 2001, and was completed in the summer of 2005. The project exceeded its budget and cost £36 million, of which Portsmouth City Council contributed £11 million.[296][297][298] The 560-foot (170 m) tower is visible at a distance of 23 miles (37 km) in clear weather, and its viewing platforms overlook the Solent (towards the Isle of Wight), the harbour and Southsea Castle.[299][300] The tower has the largest glass floor in Europe, weighing over 33,000 tonnes (32,000 long tons; 36,000 short tons).[301][300]

Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and residential area at the southern end of Portsea Island. Its name originates from Southsea Castle, a seafront castle built in 1544 by Henry VIII to help defend the Solent and Portsmouth Harbour.[302] The area was developed in 1809 as Croxton Town; by the 1860s, the suburb of Southsea had expanded to provide working-class housing.[122] Southsea developed as a seaside and bathing resort.[122] A pump room and baths were built near the present-day Clarence Pier, and a complex was developed which included vapour baths, showers, and card-playing and assembly rooms for holiday-goers.[303]

Clarence Pier, opened in 1861 by the Prince and Princess of Wales, was named after Portsmouth military governor Lord Frederick FitzClarence and was described as "one of the largest amusement parks on the south coast".[304] South Parade Pier was built in 1878, and is among the United Kingdom's 55 remaining private piers.[305][306] Originally a terminal for ferries travelling to the Isle of Wight, it was soon redeveloped as an entertainment centre. The pier was rebuilt after fires in 1904, 1967 and 1974 (during the filming of Tommy).[305][122] Plans were announced in 2015 for a Solent Eye at the pier: a £750,000, 24-gondola Ferris wheel similar to the London Eye.[307]

Southsea is dominated by Southsea Common, a 480-acre (190 ha) grassland created by draining the marshland next to the vapour baths in 1820. The common met the demands of the early-19th-century military for a clear firing range,[308] and parallels the shore from Clarence Pier to Southsea Castle.[308] A popular recreation area, it hosts a number of annual events which include carnivals, Christmas markets, and Victorian festivals.[309][310] The common has a large collection of mature elm trees, believed to be the oldest and largest surviving in Hampshire and which have escaped Dutch elm disease due to their isolation. Other plants include the Canary Island date palms (Phoenix canariensis), some of Britain's largest, which have recently produced viable seed.[311]

Religion

Portsmouth has two cathedrals: the Anglican Cathedral of St Thomas in Old Portsmouth and the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St John the Evangelist. The city is one of 34 British settlements with a Roman Catholic cathedral.[156][312] Portsmouth's first chapel, dedicated to Thomas Becket, was built by Jean de Gisors in the second half of the 12th century.[313][314] It was rebuilt and developed into a parish church and an Anglican cathedral.[314][315] Damaged during the 1642 Siege of Portsmouth, its tower and nave were rebuilt after the Restoration.[316] Significant changes were made when the Diocese of Portsmouth was founded in 1927.[317] It became a cathedral in 1932 and was enlarged, although construction was halted during the Second World War. The cathedral was re-consecrated before Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in 1991.[318]

The Royal Garrison Church was founded in 1212 by Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester. After centuries of decay, it became an ammunition store in 1540. The 1662 marriage of Charles II and Catherine of Braganza was celebrated in the church, and large receptions were held there after the defeat of Napoleon at the 1814 Battle of Leipzig. In 1941, a firebomb fell on its roof and destroyed the nave.[52] Although the church's chancel was saved by servicemen shortly after the raid, replacing the roof was deemed impossible due to the large amounts of salt solution absorbed by the stonework.[319]

The Cathedral of St John the Evangelist was built in 1882 to accommodate Portsmouth's increasing Roman Catholic population, and replaced a chapel built in 1796 to the west. Before 1791, Roman Catholic chapels in towns with borough status were prohibited. The chapel opened after the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791 was passed, and was replaced by the cathedral.[320] It was constructed in phases; the nave was completed in 1882; the crossing in 1886, and the chancel by 1893. During the blitz, the cathedral was badly damaged when Luftwaffe bombing destroyed Bishop's House next door; it was restored in 1970, 1982, and 2001.[320] The Roman Catholic Diocese of Portsmouth was founded in 1882 by Pope Leo XIII.[lower-alpha 3] Smaller places of worship in the city include St Jude's Church in Southsea,[322] St Mary's Church in Portsea,[323] St Ann's Chapel in the naval base[324] and the Portsmouth and Southsea Synagogue, one of Britain's oldest.[325]

Sport

Portsmouth F.C. play their home games at Fratton Park. They have won two Football League titles (1949 and 1950),[326][327] and won the FA Cup in 1939 and 2008.[328][329] The club returned to the Premier League in 2003.[330] They were relegated to the Championship in 2010 and, experiencing serious financial difficulties in February 2012,[331] were relegated again to League One. The club was relegated the following year to League Two, the fourth tier of English football.[332] Portsmouth F.C. was purchased in April 2013 by the Pompey Supporters Trust, becoming the largest fan-owned club in English Football history.[333][334] In May 2017, as League Two champions, they were promoted to League One for the 2017–18 season.

Moneyfields F.C. have played in the Wessex Football League Premier Division since 1998.[335] United Services Portsmouth F.C. (formerly known as Portsmouth Royal Navy) and Baffins Milton Rovers F.C. compete in Wessex League Division One; United Services was founded in 1962,[336] and Baffins Milton Rovers in 2011.[337] The rugby teams United Services Portsmouth RFC and Royal Navy Rugby Union play their home matches at the United Services Recreation Ground. Royal Navy Rugby Union play in the annual Army Navy Match at Twickenham.[338]

Portsmouth began hosting first-class cricket at the United Services Recreation Ground in 1882,[339] and Hampshire County Cricket Club matches were played there from 1895 to 2000. In 2000, Hampshire moved their home matches to the new Rose Bowl cricket ground in West End.[340] Portsmouth is home to four hockey clubs: City of Portsmouth Hockey Club, based at the university's Langstone Campus;[341] Portsmouth & Southsea Hockey Club and Portsmouth Sharks Hockey Club, based at the Admiral Lord Nelson School;[342] and United Services Portsmouth Hockey Club, based on Burnaby Road.[343] Great Salterns Golf Club, established in 1926,[344] is an 18-hole parkland course with two holes played across a lake;[345] there are coastal courses at Hayling and the Gosport and Stokes Bay Golf Club.[111] Boxing was a popular sport between 1910 and 1960, and a monument commemorating the city's boxing heritage was built in 2017.[346]

Transport

Ferries

Portsmouth Harbour has passenger-ferry links to Gosport and the Isle of Wight from the Portsmouth International Port,[347] with car-ferry service to the Isle of Wight nearby.[348] Britain's longest-standing commercial hovercraft service, begun in the 1960s, runs from near Clarence Pier to Ryde, Isle of Wight.[349] Portsmouth Continental Ferry Port has links to Caen, Cherbourg-Octeville, St Malo, and Le Havre in France,[350][351] Santander and Bilbao in Spain,[352] and the Channel Islands.[353] Ferry services from the port are operated by Brittany Ferries and Condor Ferries.[352][354][355]

On 18 May 2006, Trasmediterranea began service to Bilbao in competition with P&O's service. Its ferry, Fortuny, was detained in Portsmouth by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency for a number of safety violations.[356] They were quickly corrected, and the service was cleared for passengers on 23 May of that year.[357] Trasmediterránea discontinued its Bilbao service in March 2007, citing a need to deploy the Fortuny elsewhere.[358] P&O Ferries ended their service to Bilbao on 27 September 2010 due to "unsustainable losses".[359][360] The second-busiest ferry port in the UK (after Dover), Portsmouth handles about three million passengers per year.[361][362]

Buses

Local bus service is provided by Stagecoach South East and First Hampshire & Dorset to the city and its surrounding towns. Hovertravel and Stagecoach operate a Hoverbus service from the city centre to Southsea Hovercraft Terminal and the Hard Interchange, near the seafront.[363] Countryliner operates a Saturday service to Midhurst in West Sussex,[364] and Xelabus operated a Sunday open-top seafront summer service around the city as of 2012.[365] National Express service from Portsmouth operates primarily from the Hard Interchange to London Victoria station, Cornwall, Bradford, Birkenhead and Bristol.[366]

Railways

Portsmouth has four mainline railway stations: Hilsea, Fratton, Portsmouth & Southsea[367] and Portsmouth Harbour.[368] The city is on two direct South Western Railway routes to London Waterloo, via Guildford and Basingstoke.[369] There is a South Western Railway stopping service to Southampton Central and Great Western Railway service to Cardiff Central via Southampton, Salisbury, Bath Spa and Bristol.[370] Southern has service to Brighton, Gatwick Airport, Croydon, and London Victoria.[371]

From 1885 to 1914, the Southsea Railway operated between Southsea and Fratton. It was closed in 1914 due to competition from tram and trolleybus services.[372]

Air

Portsmouth Airport, with a grass runway, was in operation from 1932 to 1973. After it closed, housing (Anchorage Park), industry, stores (Ocean Retail Park) and a school (Admiral Lord Nelson School) were built on the site.[373][374] The nearest airport is Southampton Airport in the Borough of Eastleigh, 19.8 miles (31.9 km) away.[111] It has a South Western Railway rail connection, requiring a change at Southampton Central or Eastleigh.[375] Heathrow and Gatwick are 65 miles (105 km) and 75 miles (121 km) away, respectively. Gatwick is linked by Southern train service to London Victoria station and Heathrow is linked by coach to Woking, which is on both rail lines to London Waterloo and the London Underground.[376] Heathrow is linked to Portsmouth by National Express coaches.[377]

Former canal

The Portsmouth and Arundel Canal ran between the towns and was built in 1823 by the Portsmouth & Arundel Navigation Company. Never financially successful, it was abandoned in 1855 and the company was wound up in 1888.[378] The canal was part of a larger scheme for a secure inland canal route from London to Portsmouth, allowing boats to avoid the English Channel. It had three sections: a pair of ship canals (one on Portsea Island and one to Chichester) and a barge canal from Ford on the River Arun to Hunston, where it joined the canal's Chichester section.[379]

The route through Portsea Island began from a basin formerly located on Arundel Street and cut through Landport, Fratton and Milton, ending at the eastern end of Locksway Road in Milton (where a set of lock gates accessed Langstone and Chichester Harbours. After the island route was closed, the drained canal-bed sections through Milton, Fratton and Landport were reused for the Portsmouth Direct line.

The brick-lined canal walls are clearly visible between the Fratton and Portsmouth & Southsea railway stations. The canal lock entrance at Locksway Road in Milton is east of the Thatched House, a pub.[380]

Possible public transport projects

There is an ongoing debate on the development of a new public transport structure, with monorails and light rail both being considered. A light rail link to Gosport was authorised in 2002 with completion expected in 2005, but it is unlikely that the project will be completed following the refusal of funding by the Department for Transport in November 2005.[381] In April 2011, an article appeared in Portsmouth News suggesting a new scheme could be in the offing by running a light rapid transit system over the line to Southampton via Fareham, Bursledon, and Sholing, thus replacing the existing heavy rail services.[382][383]

Media

Portsmouth, along with Southampton and its adjacent towns, are served predominantly with transmissions from the Rowridge and Chillerton Down transmitters on the Isle of Wight,[384] though the transmitter at Midhurst can provide a substitute for Rowridge. Portsmouth was one of the first cities in the UK to have a local TV station, MyTV; although the Isle of Wight had a local television service which began broadcasting in 1998.[385] In November 2014, a new TV station, named That's Solent, was launched as part of a nationwide roll-out of local Freeview channels in south central England.[386] The stations are broadcast from Rowridge.[387]

Popular radio stations according to RAJAR include regional station Wave 105 from Bauer Media and Global Radio's Heart and Capital FM. The Breeze is broadcast from Southampton to the city on 107.4FM,[388] while the city also has a non-profit community radio station Express FM on 93.7FM.[389] Patients at Portsmouth's primary hospital, Queen Alexandra in Milton, also have access to local programming from charity station Portsmouth Hospital Broadcasting, which starting broadcasting in 1951.[390] When the first local commercial radio stations were licensed in the 1970s by the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA), Radio Victory won the first licence and began broadcasting in 1975. In 1986, the IBA increased the Portsmouth licence to include Southampton and the Isle of Wight. Radio Victory were not awarded the new licence, which went to Ocean Sound, later known as Ocean FM who based their studios in Fareham. Ocean FM would become Heart Hampshire. For the city's 800th birthday in 1994, Victory FM broadcast for three 28-day periods over an 18-month period.[391] It was purchased from the founders by TLRC, who, due to poor RAJAR figures, relaunched the service in 2001 as The Quay,[392] with Portsmouth Football Club purchasing a stake in the station during 2007 and selling it in 2009.[393]

The city currently has one daily local newspaper known as The News. The paper was established in 1873 and was previously known as the Portsmouth Evening News. A free weekly newspaper is published by the same publisher, Johnston Press, called The Journal.[394][395]

Notable residents

The city has been home to a number of famed authors. Most notably Charles Dickens – known for such works as Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, and The Pickwick Papers – was born in Portsmouth.[396] Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, practised as a doctor in the city and played in goal for Portsmouth Association Football Club, an amateur team not to be confused with the later professional Portsmouth Football Club.[397] Rudyard Kipling, poet and author of the Jungle Book,[398] and H. G. Wells, author of War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, lived in Portsmouth during the 1880s.[399] Sir Walter Besant, a novelist and historian, was born in Portsmouth,[400] writing one novel set exclusively in the town, By Celia's Arbour, A Tale of Portsmouth Town.[401] Historian Frances Yates was born in Portsmouth and is known for her work on Renaissance esotericism. Sir Francis Austen, brother of Jane Austen, briefly lived in the area after graduating from Portsmouth Naval Academy.[402] More contemporary Portsmouth literary figures include social critic, journalist, and author Christopher Hitchens, who was born in the city.[403] Nevil Shute moved to Portsmouth in 1934 when he relocated his aircraft company to the city; his former home stands in Southsea.[404] Fantasy author Neil Gaiman grew up in nearby Purbrook and the Portsmouth suburb of Southsea, and in 2013 had a Southsea road named after his novel The Ocean at the End of the Lane.[235][405]

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, a famed engineer of the Industrial Revolution, was born in Portsmouth.[406][407] His father Marc Isambard Brunel worked for the Royal Navy and invented the world's first production line to mass manufacture pulley blocks for the rigging in Royal Navy vessels.[69] James Callaghan, who was British prime minister from 1976 to 1979, was born and raised in Portsmouth.[408][409] He was the son of a Protestant Northern Irish petty officer in the Royal Navy and was also the only person to have held all four Great Offices of State, having previously served as foreign secretary, home secretary, and chancellor.[410] John Pounds, the founder of the ragged school, which provided free education to working class children, lived in Portsmouth and set up the country's first ragged school in the city.[411]

Peter Sellers, comedian, actor, and performer, was born in Southsea,[412] and Arnold Schwarzenegger lived and trained in Portsmouth for a short time.[413] Several other professional actors have also been born, or lived, in the city, including EastEnders actresses Emma Barton and Lorraine Stanley,[414] and Bollywood actress Geeta Basra.[415] Cryptozoologist Jonathan Downes was born and lived in Portsmouth for a time.[416] Helen Duncan, the last person to be imprisoned under the 1735 Witchcraft Act in the UK, was arrested in Portsmouth.[417]Roland Orzabal main songwriter and joint vocalist of Tears for Fears was born in Portsmouth, as was Roger Hodgson, musician and front figure of renowned band Supertramp.

Notable sportspeople from Portsmouth include Michael East, a Commonwealth Games gold medal-winning athlete,[418] Rob Hayles, cyclist and Olympic Games medal winner,[419] Tony Oakey, former British light-heavyweight boxing champion,[420] and Alan Pascoe, an Olympic medallist.[421] Sir Alec Rose, single-handed yachtsman,[422] Katy Sexton, former world champion swimmer who won gold in the 200 metres (660 ft) backstroke at the 2003 World Aquatics Championships in Barcelona,[423] and Roger Black, an Olympic medallist, were also born in Portsmouth.[424]

Jamshid bin Abdullah of Zanzibar, the last constitutional monarch of that island state, lives in exile in Portsmouth with his wife and six children.[425]

Freedom of the City

According to Portsmouth City Council's official website, the following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Portsmouth.[426]

Individuals

- Baron Macnaghten GCB GCMG PC: 1895.

- Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar VC KG KP OM GCSI GCIE VD PC FRSGS: 1898.

- Alderman Sir John Baker MP JP: 1901.

- Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Fitzwygram Bt MP: 1901.

- Alderman Sir William Pink JP: 1905.

- Alderman Sir T. Scott Foster JP: 1906.

- Duke of Connaught and Strathearn: 1921.

- Alderman F. G. Foster JP: 1924.

- David Lloyd George OM PC: 1924.

- Prince of Wales: 1926.

- Major General J. E. B. Seely CB CMG DSO TD PC JP DL: 1927.

- Sir William Joynson-Hicks Bt PC PC (NI) DL: 1927.

- Councillor Frank J. Privett JP: 1928.

- Alderman Sir Harold R. Pink JP : 1928.

- Admiral Sir William James GCB: 1942.

- Field Marshal Lord Montgomery of Alamein KG GCB DSO PC DL: 1946.

- Sir Winston Churchill KG OM CH TD DL FRS RA: 12 December 1950.[427]

- Alderman Albert Johnson: 1966.

- Alderman J. P. D. Lacey OBE JP: 1966.

- Sir Alec Rose: 1968.[428]

- Admiral of the Fleet Lord Mountbatten of Burma KG GCB OM GCSI GCIE GCVO DSO PC FRS: 1976.

- Prince of Wales: 1979.

- Lord Callaghan of Cardiff KG PC: 1991.

- Princess of Wales: 1992.

- Lord Judd of Portsea: 1995.

- Lady Margaret Daley MBE: 1996.

- Herr Josef Krings OBE: 1997.

- Ian G. Gibson OBE: 2002.

- Milan Mandarić: 2003.

- Sir Alfred Blake KCVO MC DL: 2003.

- Brian Kidd: 2003.

- Harry Redknapp: 2008.

- Syd Rapson: 2016.

Military units

- The Royal Hampshire Regiment: 1950.

- The Royal Marines: 1959.

- The Portsmouth Command of the Royal Navy: 1965.

- The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment: 1992.

- HMS King Alfred, RNR: 2003.

- HMS Endurance, RN: 2007.

See also

Notes

- These were part of a network of fortifications intended to guard military bases on the British coastline from an inland attack. They were built in the 19th century by order of Lord Palmerston.[74]

- Portsmouth is one of 34 British towns and cities with a Catholic cathedral.[156][157]

- Vatican policy in England at the time was to found sees in locations other than those used for Anglican cathedrals.[321]

References

Citations

- "Portsmouth Census Summary, Hampshire County Council" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "British urban pattern: population data" (PDF). ESPON project 1.4.3 Study on Urban Functions. European Union – European Spatial Planning Observation Network. March 2007. pp. 120–121. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Ethnic Group by District" (PDF). Hampshire County Council. 2011. p. 38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- "FAQs". Visit Portsmouth. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Page, William (1908). "The liberty of Portsmouth and Portsea Island: Introduction". A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3. Victoria County History. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- "1926 - Portsmouth Created a City". Portsmouth Royal Dockyard Historical Trust. 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Portsmouth - Coat of arms (Crest) of Portsmouth".

- "Portsmouth 800".

- Amy, Robert. "Classic Britannica – the home of the Roman Fleet". Pompeymarkets. PM Ltd. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Portsmouth name origin". Key to English Place-names. University of Nottingham. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Vortigern in the Sources: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle". VortigernStudies. Robert Vermaat. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Churchill 2015, p. 41.

- "See Portsmouth through history". The Independent. 6 May 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Allen 2015, p. 26.

- Allen 2015, p. 27.

- Allen 2015, p. 29.

- Allen 2015, p. 30.

- Allen 2015, p. 31.

- "History of Portsmouth". Portsmouth Council. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "A History of Portsmouth". Local Histories. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- Allen 2015, p. 32.

- Allen 2015, p. 33.

- Quail 1994, pp. 14–18.

- Allen 2015, p. 34.

- Allen 2015, p. 36.

- Allen 2015, p. 37.

- Allen 2015, pp. 37, 39.

- Allen 2015, p. 43.

- Allen 2015, p. 44.

- Sumption 1990, pp. 395, 396.

- Seward 1988.

- "Portsmouth port history". World Post Source. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Allen 2015, p. 48.

- Allen 2015, p. 49.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 27.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 33.

- Allen 2015, p. 53.

- "Portsmouth's long shipbuilding history comes to an end". BBC. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- Allen 2015, p. 143.

- "Two Programmes – Coast, Shorts, Cuttlefish and Pompey". BBC. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 23.

- "Portsmouth's Coat of Arms". Portsmouth City Council. 29 May 2007. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- "Southsea Castle History". Portsmouth Museums. 2015.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 37.

- Allen 2015, p. 54.

- Allen 2015, pp. 54, 55.

- Allen 2015, p. 56.

- Backhouse, Tim. "Old Portsmouth—Duke of Buckingham". Memorials and Monuments in Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- "The Siege of Portsmouth". Portsmouth History. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "The Siege of Portsmouth, August to September 1642". Little Woodham. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Allen 2015, p. 57.

- "Royal Garrison Church, Portsmouth". English Heritage. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 57.

- Allen 2015, p. 58.

- Allen 2015, p. 65.

- Collingridge 2003, p. 311.

- "The First Fleet". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- Frost 2012, p. 165.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 223.

- Hewitt 2013, pp. 223, 224.

- Hough 1972, p. 276.

- Allen 2015, p. 130.

- "Pompey, Chats and Guz: the Origins of Naval Town nicknames". Royal Naval Museum. 2000. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 98.

- Breverton 2010, p. 282.

- Berry & Glover 1828.

- East 1891, p. 656.

- Valentine Dyall, Unsolved Mysteries: A Collection of Weird Problems from the Past, 1954, p. 14).

- "Portsmouth Royal Dockyard history: 1690–1840". Portsmouth Royal Dockyard. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Portsmouth Dockyard Block Mills history". Portsmouth Guide. Portsmouth Council. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Shipbuilding & The Dockyard". A Tale of One City. Portsmouth City Council. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 39.

- Pevsner 1967, p. 422.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 79.

- "From slave trade to humanitarian aid". BBC News. 19 March 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- "A History of Portsmouth Water Supply". Welcome to Portsmouth. Portsmouth City Council. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "John Pounds Memorial Church". InPortsmouth. CIS. Archived from the original on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Hewitt 2013, pp. 66, 67.

- Rice 1999, pp. 27–48.

- "The Voyage of the Challenger". Stony Brook University. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 24.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 91.

- "Portsmouth Zeppelin air raid". Richthofen.com. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Portsmouth Dockyard, Hampshire: Mystery Zeppelin Attack". BBC. 30 July 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- "No. 33154". The London Gazette. 23 April 1926. pp. 2776–2777.

- "Portsmouth's Coat of Arms history". Portsmouth City Council. 27 November 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- "Guildhall History – Portsmouth Guildhall". www.portsmouthguildhall.org.uk. Portsmouth City Council. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Portsmouth Guildhall bombed during WWII". Portsmouthnowandthen.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "The Blitz, Portsmouth". Welcometoportsmouth.co.uk. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 151.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 186.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 147.

- Hewitt 2013, p. 146.

- Hewitt 2013, pp. 155, 156.