Māori language

Māori (/ˈmaʊri/; Māori pronunciation: [ˈmaːɔɾi] ![]()

| Māori | |

|---|---|

| Māori, Te reo Māori | |

| Native to | New Zealand |

| Region | Polynesia |

| Ethnicity | Māori people |

Native speakers | Some 50,000 people report that they speak the language well or very well;[1] 149,000 self-report some knowledge of the language.[2] |

Austronesian

| |

| Latin (Māori alphabet) Māori Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Māori Language Commission |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | mi |

| ISO 639-2 | mao (B) mri (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | mri |

| Glottolog | maor1246[3] |

| Linguasphere | 39-CAQ-a |

| Māori topics |

|---|

|

|

Society

|

|

Lists

|

|

|

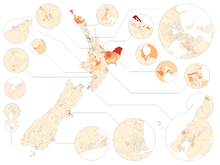

A national census undertaken in 2013 reported that about 149,000 people, or 3.7% of the New Zealand population, could hold a conversation in Māori about everyday things.[2][6] As of 2015, 55% of Māori adults reported some knowledge of the language; of these, 64% use Māori at home and around 50,000 people can speak the language "very well" or "well".[1]

The Māori language did not have an indigenous writing system. Missionaries arriving from about 1814 learned to speak Māori, and introduced the Latin alphabet. In 1817 Tītore, and his junior relative, Tui, sailed to England.[7] They visited Professor Samuel Lee at Cambridge University and assisted him in the preparation of a grammar and vocabulary of Māori. Kendall travelled to London in 1820 with Hongi Hika and Waikato (a lower ranking Ngāpuhi chief) during which time further work was done with Professor Lee, who gave phonetic spellings to a written form of the language, which resulted in a definitive orthography based on Northern usage.[8] By 1830 the Church Missionary Society (CMS) missionaries had revised the orthography for writing the Māori language; for example, "Kiddeekiddee" became, what is the modern spelling, "Kerikeri".[9] Māori distinguishes between long and short vowels; modern written texts usually mark the long vowels with a macron. Some older texts represent long vowels with double letters (e.g. "Maaori"); for modern exceptions see § Long vowels below.

Name

The English word comes from the Māori language, where it is spelled Māori. In New Zealand, the Māori language is often referred to as te reo [tɛ ˈɾɛ.ɔ] ('the language'), short for te reo Māori.[10]

The spelling ⟨Maori⟩ (without a macron) is standard in English outside New Zealand in both general and linguistic usage.[2][11] The Māori-language spelling ⟨Māori⟩ (with a macron) has become common in New Zealand English in recent years, particularly in Māori-specific cultural contexts,[10][12] although the traditional English spelling is still prevalent in general media and government use.[13]

Preferred and alternate pronunciations in English vary by dictionary, with /ˈmaʊri/ being most frequent today (although it is an incorrect pronunciation), and /mɑːˈɒri/, /ˈmɔːri/, and /ˈmɑːri/ also given, while the 'r' is always a rolled r.[14]

Official status

New Zealand has three official languages: English, Māori, and New Zealand Sign Language.[15] Māori gained this status with the passing of the Māori Language Act 1987.[16] Most government departments and agencies have bilingual names—for example, the Department of Internal Affairs Te Tari Taiwhenua—and places such as local government offices and public libraries display bilingual signs and use bilingual stationery. New Zealand Post recognises Māori place-names in postal addresses. Dealings with government agencies may be conducted in Māori, but in practice, this almost always requires interpreters, restricting its everyday use to the limited geographical areas of high Māori fluency, and to more formal occasions, such as during public consultation. Increasingly New Zealand is referred to by the Māori name Aotearoa ("land of the long white cloud"), though originally this referred only to the North Island.[17]

An interpreter is on hand at sessions of the New Zealand Parliament for instances when a Member wishes to speak in Māori.[12][18] Māori may be spoken in judicial proceedings, but any party wishing to do so must notify the court in advance to ensure an interpreter is available. Failure to notify in advance does not preclude the party speaking in Māori, but the court must be adjourned until an interpreter is available and the party may be held liable for the costs of the delay.[19]

A 1994 ruling by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council[20] in the United Kingdom held the New Zealand Government responsible under the Treaty of Waitangi (1840) for the preservation of the language. Accordingly, since March 2004, the state has funded Māori Television, broadcast partly in Māori. On 28 March 2008, Māori Television launched its second channel, Te Reo, broadcast entirely in the Māori language, with no advertising or subtitles. The first Māori TV channel, Aotearoa Television Network (ATN) was available to viewers in the Auckland region from 1996 but lasted for only one year.[21]

In 2008, Land Information New Zealand published the first list of official place names with macrons, which indicate long vowels. Previous place name lists were derived from computer systems (usually mapping and geographic information systems) that could not handle macrons.[22]

History

According to legend, Māori came to New Zealand from Hawaiki. Current anthropological thinking places their origin in eastern Polynesia, mostly likely from the Southern Cook or Society Islands region, and says that they arrived by deliberate voyages in seagoing canoes[23]—possibly double-hulled, and probably sail-rigged. These settlers probably arrived by about AD 1280 (see Māori origins). Their language and its dialects developed in isolation until the 19th century.

Since about 1800, the Māori language has had a tumultuous history. It started this period as the predominant language of New Zealand. In the 1860s, it became a minority language in the shadow of the English spoken by many settlers, missionaries, gold-seekers, and traders. In the late 19th century, the colonial governments of New Zealand and its provinces introduced an English-style school system for all New Zealanders. From the mid 1800s, due to the Native Schools Act and later the Native Schools Code, the use of Māori in schools was slowly filtered out of the curriculum in order to become more European.[24] Increasing numbers of Māori people learned English.

Decline

Until the Second World War (1939–1945), most Māori people spoke Māori as their first language. Worship took place in Māori; it functioned as the language of Māori homes; Māori politicians conducted political meetings in Māori, and some literature appeared in Māori, along with many newspapers.[25]

Before 1880, some Māori parliamentarians suffered disadvantages because Parliament's proceedings took place in English.[26] However, by 1900, all Māori members of parliament, such as Sir Āpirana Ngata, were university graduates who spoke fluent English. From this period greater emphasis was placed on Māori learning English, but it was not until the post World War II migration of Māori to urban areas that the number of speakers of Māori began to decline rapidly.[27] By the 1980s, fewer than 20% of the Māori spoke the language well enough to be classed as native speakers. Even many of those people no longer spoke Māori in the home. As a result, many Māori children failed to learn their ancestral language, and generations of non-Māori-speaking Māori emerged.[28]

Revitalisation efforts

By the 1980s, Māori leaders had begun to recognise the dangers of the loss of their language, and initiated Māori-language recovery-programs such as the Kōhanga Reo movement, which from 1982 immersed infants in Māori from infancy to school age. There followed in 1985 the founding of the first Kura Kaupapa Māori (Years 1 to 8 Māori-medium education programme) and later the first Wharekura (Years 9 to 13 Māori-medium education programme). Although "there was a true revival of te reo in the 1980s and early to mid-1990s ... spurred on by the realisation of how few speakers were left, and by the relative abundance of older fluent speakers in both urban neighbourhoods and rural communities", the language has continued to decline.[4] The decline is believed "to have several underlying causes".[29] These include:

- the ongoing loss of older native speakers who have spearheaded the Māori-language-revival movement

- complacency brought about by the very existence of the institutions which drove the revival

- concerns about quality, with the supply of good teachers never matching demand (even while that demand has been shrinking)

- excessive regulation and centralised control, which has alienated some of those involved in the movement

- an ongoing lack of educational resources needed to teach the full curriculum in te reo Māori.[29]

Based on the principles of partnership, Māori-speaking government, general revitalisation and dialectal protective policy, and adequate resourcing, the Waitangi Tribunal has recommended "four fundamental changes":[30]

- Te Taura Whiri (the Māori Language Commission) should become the lead Māori language sector agency. This will address the problems caused by the lack of ownership and leadership identified by the Office of the Auditor-General.[31]

- Te Taura Whiri should function as a Crown–Māori partnership through the equal appointment of Crown and Māori appointees to its board. This reflects [the Tribunal's] concern that te reo revival will not work if responsibility for setting the direction is not shared with Māori.

- Te Taura Whiri will also need increased powers. This will ensure that public bodies are compelled to contribute to te reo's revival and that key agencies are held properly accountable for the strategies they adopt. For instance, targets for the training of te reo teachers must be met, education curricula involving te reo must be approved, and public bodies in districts with a sufficient number and/or proportion of te reo speakers and schools with a certain proportion of Māori students must submit Māori language plans for approval.

- These regional public bodies and schools must also consult iwi (Māori tribes or tribal confederations) in the preparation of their plans. In this way, iwi will come to have a central role in the revitalisation of te reo in their own areas. This should encourage efforts to promote the language at the grassroots.[32]

The changes set forth by the Tribunal are merely recommendations; they are not binding upon government.[33]

There is however evidence that the revitalisation efforts are taking hold, as can be seen in the teaching of te reo in the school curriculum, the use of Māori as an instructional language, and the supportive ideologies surrounding these efforts.[34] In 2014, a survey of students ranging in age from 18–24 was conducted; the students were of mixed ethnic backgrounds, ranging from Pākehā to Māori who lived in New Zealand. This survey showed a 62% response saying that te reo Māori was at risk.[34] Albury argues that these results come from the language either not being used enough in common discourse, or from the fact that the number of speakers was inadequate for future language development.[34]

The policies for language revitalisation have been changing in attempts to improve Māori language use and have been working with suggestions from the Waitangi Tribunal on the best ways to implement the revitalisation. The Waitangi Tribunal in 2011 identified a suggestion for language revitalisation that would shift indigenous policies from the central government to the preferences and ideologies of the Māori people.[33] This change recognises the issue of Māori revitalisation as one of indigenous self-determination, instead of the job of the government to identify what would be best for the language and Māori people of New Zealand.[35]

Revival since 2015

Beginning in about 2015, the Māori language underwent a revival as it became increasingly popular, as a common national heritage, even among New Zealanders without Māori roots. Surveys from 2018 indicated that "the Māori language currently enjoys a high status in Māori society and also positive acceptance by the majority of non-Māori New Zealanders".[5]

As the status and prestige of the language rose, so did the demand for language classes. Businesses were quick to adopt the trend as it became apparent that using te reo made customers think of a company as "committed to New Zealand".[5] The language became increasingly heard in the media and in politics. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern—who gave her daughter a Māori middle name—made headlines when she toasted Commonwealth leaders in 2018 with a Māori proverb, and the success of Māori musical groups such as Alien Weaponry and Maimoa further increased the language's presence in social media.[5]

In 2019, Kotahi Rau Pukapuka Trust began work on publishing a sizeable library of local and international literature in the language.[36] In 2019, a Te Reo card game (Tākaro) was created by Hamilton entrepreneurs.[37] By 2020, there was a brand that aimed to help mums promote te reo Māori in their homes through hand-made taonga.[38]

Linguistic classification

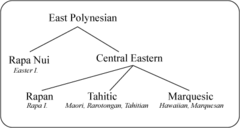

Comparative linguists classify Māori as a Polynesian language; specifically as an Eastern Polynesian language belonging to the Tahitic subgroup, which includes Cook Islands Māori, spoken in the southern Cook Islands, and Tahitian, spoken in Tahiti and the Society Islands. Other major Eastern Polynesian languages include Hawaiian, Marquesan (languages in the Marquesic subgroup), and the Rapa Nui language of Easter Island.[39][40][41]

While the preceding are all distinct languages, they remain similar enough that Tupaia, a Tahitian travelling with Captain James Cook in 1769–1770, communicated effectively with Māori.[42] Māori actors, travelling to Easter Island for production of the film Rapa-Nui noticed a marked similarity between the native tongues, as did arts curator Reuben Friend, who noted that it took only a short time to pick up any different vocabulary and the different nuances to recognisable words.[43] Speakers of modern Māori generally report that they find the languages of the Cook Islands, including Rarotongan, the easiest amongst the other Polynesian languages to understand and converse in.

Geographic distribution

Nearly all speakers are ethnic Māori resident in New Zealand. Estimates of the number of speakers vary: the 1996 census reported 160,000,[44] while other estimates have reported as few as 10,000 fluent adult speakers in 1995 according to the Māori Language Commission.[45] As reported in the 2013 national census, only 21.31 per cent of Māori (self-identified) had a conversational knowledge of the language, and only around 6.5 per cent of those speakers, 1.4 per cent of the total Māori population, spoke the Māori language only. This percentage has been in decline in recent years, from around a quarter of the population to 21 per cent. However, the number of speakers In the same census, Māori speakers were 3.7 per cent of the total population.[6]

The level of competence of self-professed Māori speakers varies from minimal to total. Statistics have not been gathered for the prevalence of different levels of competence. Only a minority of self-professed speakers use Māori as their main language at home.[46] The rest use only a few words or phrases (passive bilingualism).

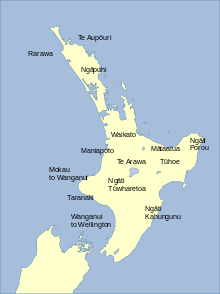

Māori still is a community language in some predominantly-Māori settlements in the Northland, Urewera and East Cape areas. Kohanga reo Māori-immersion kindergartens throughout New Zealand use Māori exclusively. Increasing numbers of Māori raise their children bilingually.[46]

Urbanisation after the Second World War led to widespread language shift from Māori predominance (with Māori the primary language of the rural whānau) to English predominance (English serving as the primary language in the Pākehā cities). Therefore, Māori-speakers almost always communicate bilingually, with New Zealand English as either their first or second language. Only around 9,000 people speak only in Māori.[35]

The use of the Māori language in the Māori diaspora is far lower than in New Zealand itself. Census data from Australia show it as the home language of 11,747, just 8.2% of the total Australian Māori population in 2016. However, this could just be due to more Māori immigrants leaving to Australia.[47]

Orthography

There was originally no native writing system for Māori. It has been suggested that the petroglyphs once used by the Māori developed into a script similar to the Rongorongo of Easter Island.[48] However, there is no evidence that these petroglyphs ever evolved into a true system of writing. Some distinctive markings among the kōwhaiwhai (rafter paintings) of meeting houses were used as mnemonics in reciting whakapapa (genealogy) but again, there was no systematic relation between marks and meanings.

The modern Māori alphabet has 15 letters, two of which are digraphs: A E H I K M N O P R T U W NG and WH.[49] The five vowels have both short and long forms, with the long forms denoted by macrons marked above them - Ā, Ē, Ī, Ō and Ū. Attempts to write Māori words using the Latin script began with Captain James Cook and other early explorers, with varying degrees of success. Consonants seem to have caused the most difficulty, but medial and final vowels are often missing in early sources. Anne Salmond[50] records aghee for aki (In the year 1773, from the North Island East Coast, p. 98), Toogee and E tanga roak for Tuki and Tangaroa (1793, Northland, p216), Kokramea, Kakramea for Kakaramea (1801, Hauraki, p261), toges for toki(s), Wannugu for Uenuku and gumera for kumara (1801, Hauraki, p261, p266, p269), Weygate for Waikato (1801, Hauraki, p277), Bunga Bunga for pungapunga, tubua for tupua and gure for kurī (1801, Hauraki, p279), as well as Tabooha for Te Puhi (1823, Northern Northland, p385).

From 1814, missionaries tried to define the sounds of the language. Thomas Kendall published a book in 1815 entitled A korao no New Zealand, which in modern orthography and usage would be He Kōrero nō Aotearoa. Beginning in 1817, Professor Samuel Lee of Cambridge University worked with the Ngāpuhi chief Tītore and his junior relative Tui (also known as Tuhi or Tupaea),[8] and then with chief Hongi Hika[51] and his junior relative Waikato; they established a definitive orthography based on Northern usage, published as the First Grammar and Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language (1820).[8] The missionaries of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) did not have a high regard for this book. By 1830 the CMS missionaries had revised the orthography for writing the Māori language; for example, ‘Kiddeekiddee’ became, what is the modern spelling, ‘Kerikeri’.[9] This orthography continues in use, with only two major changes: the addition of wh to distinguish the voiceless bilabial fricative phoneme from the labio-velar phoneme /w/; and the consistent marking of long vowels.

The Māori embraced literacy enthusiastically, and missionaries reported in the 1820s that Māori all over the country taught each other to read and write, using sometimes quite innovative materials in the absence of paper, such as leaves and charcoal, and flax.[52] Missionary James West Stack recorded the scarcity of slates and writing materials at the Native schools and the use sometimes of "pieces of board on which sand was sprinkled, and the letters traced upon the sand with a pointed stick".[53]

Long vowels

The alphabet devised at Cambridge University does not mark vowel length. The following examples show that vowel length is phonemic in Māori:

| ata | morning | āta | 'carefully' |

| keke | cake | kēkē | 'armpit' |

| mana | prestige | māna | 'for him/her' |

| manu | bird | mānu | 'to float' |

| tatari | to wait for | tātari | 'to filter or analyse' |

| tui | to sew | tūī | 'Parson bird' |

| wahine | woman | wāhine | 'women' |

Māori devised ways to mark vowel length, sporadically at first. Occasional and inconsistent vowel-length markings occur in 19th-century manuscripts and newspapers written by Māori, including macron-like diacritics and doubling of letters. Māori writer Hare Hongi (Henry Stowell) used macrons in his Maori-English Tutor and Vade Mecum of 1911,[54] as does Sir Āpirana Ngata (albeit inconsistently) in his Maori Grammar and Conversation (7th printing 1953). Once the Māori language was taught in universities in the 1960s, vowel-length marking was made systematic. At Auckland University, Professor Bruce Biggs (of Ngāti Maniapoto descent) promoted the use of double vowels (e.g. Maaori); this style was standard there until Biggs died in 2000.

Macrons (tohutō) are now the standard means of indicating long vowels,[55] after becoming the favoured option of the Māori Language Commission—set up by the Māori Language Act 1987 to act as the authority for Māori spelling and orthography.[56][57] Most media now use macrons; Stuff websites and newspapers since 2017,[58] TVNZ[59] and NZME websites and newspapers since 2018.[60]

Technical limitations in producing macronised vowels on typewriters and older computer systems are sometimes resolved by using a diaeresis instead of a macron (e.g., Mäori).[61]

Double vowels continue to be used in a few cases, including:

- The Waikato-Tainui iwi preference is for using doubled vowels;[62] hence in the Waikato region, double vowels are used by the Hamilton City Council,[63] Waikato District Council[64] and Waikato Museum,

- Inland Revenue continues to spell its Māori name Te Tari Taake instead of Te Tari Tāke, mainly to reduce the resemblance of tāke to the English word take.[65]

- A considerable number of governmental and non-governmental organisations continue to use the older spelling of ⟨roopu⟩ ('association') in their names rather than the more modern form ⟨rōpū⟩. Examples include Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa ('the national Māori weavers' collective') and Te Roopu Pounamu (a Māori-specific organisation within the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand).

Phonology

Māori has five phonemically distinct vowel articulations, and ten consonant phonemes.

Vowels

Although it is commonly claimed that vowel realisations (pronunciations) in Māori show little variation, linguistic research has shown this not to be the case.[66]

Vowel length is phonemic; but four of the five long vowels occur in only a handful of word roots, the exception being /aː/.[67] As noted above, it has recently become standard in Māori spelling to indicate a long vowel with a macron. For older speakers, long vowels tend to be more peripheral and short vowels more centralised, especially with the low vowel, which is long [aː] but short [ɐ]. For younger speakers, they are both [a]. For older speakers, /u/ is only fronted after /t/; elsewhere it is [u]. For younger speakers, it is fronted [ʉ] everywhere, as with the corresponding phoneme in New Zealand English.

As in many other Polynesian languages, diphthongs in Māori vary only slightly from sequences of adjacent vowels, except that they belong to the same syllable, and all or nearly all sequences of nonidentical vowels are possible. All sequences of nonidentical short vowels occur and are phonemically distinct.[68] With younger speakers, /ai, au/ start with a higher vowel than the [a] of /ae, ao/.

The following table shows the five vowel phonemes and the allophones for some of them according to Bauer 1997 and Harlow 2006. Some of these phonemes occupy large spaces in the anatomical vowel triangle (actually a trapezoid) of tongue positions. For example, as above, /u/ is sometimes realised as [ʉ].

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ⟨i⟩ [i], [iː] | ⟨u⟩ [ʉ], [uː] | |

| Mid | ⟨e⟩ [ɛ], [eː] | ⟨o⟩ [ɔ], [oː] | |

| Open | ⟨a⟩ [ɐ], [ɑː][69] | ||

Beside monophthongs Māori has many diphthong vowel phonemes. Although any short vowel combinations are possible, researchers disagree on which combinations constitute diphthongs.[70] Formant frequency analysis distinguish /aĭ/, /aĕ/, /aŏ/, /aŭ/, /oŭ/ as diphthongs.[71]

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Māori are listed in the following table. Seven of the ten Māori consonant letters have the same pronunciation as they do in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For those that do not, the IPA phonetic transcription is included, enclosed in square brackets per IPA convention.

| Labial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ng [ŋ] |

|

| Plosive | p | t | k | |

| Fricative | wh [f, ɸ] |

h | ||

| Tap | r [ɾ] |

|||

| Approximant | w |

The pronunciation of ⟨wh⟩ is extremely variable,[72] but its most common pronunciation (its canonical allophone) is the labiodental fricative, IPA [f] (as found in English). Another allophone is the bilabial fricative, IPA [ɸ], which is usually supposed to be the sole pre-European pronunciation, although linguists are not sure of the truth of this supposition. At least until the 1930s, the bilabial fricative was considered to be the correct pronunciation.[73] The fact that English ⟨f⟩ gets substituted by ⟨p⟩ and not ⟨wh⟩ in borrowings (for example, English February becomes Pēpuere instead of *Whēpuere) would strongly hint that the Māori did not perceive English /f/ to be the same sound as their ⟨wh⟩.

Because English stops /p, t, k/ primarily have aspiration, speakers of English often hear the Māori nonaspirated stops as English /b, d, ɡ/. However, younger Māori speakers tend to aspirate /p, t, k/ as in English. English speakers also tend to hear Māori /r/ as English /l/ in certain positions (cf. Japanese r). These ways of hearing have given rise to place-name spellings which are incorrect in Māori, like Tolaga Bay in the North Island and Otago and Waihola in the South Island.

/ŋ/ can come at the beginning of a word (like sing-along without the "si"), which is difficult for English speakers outside of New Zealand to manage.

/h/ is pronounced as a glottal stop, [ʔ], and the sound of ⟨wh⟩ as [ʔw], in some western areas of North Island.

/ɾ/ is typically a flap, especially before /a/. However, elsewhere it is sometimes trilled.

In borrowings from English, many consonants are substituted by the nearest available Māori consonant. For example, the English fricatives /tʃ/, /dʒ/, and /s/ are replaced by /h/, /f/ becomes /p/, and /l/ becomes /ɾ/ (the /l/ is sometimes retained in the southern dialect, as noted below).

Syllables and phonotactics

Syllables in Māori have one of the following forms: V, VV, CV, CVV. This set of four can be summarised by the notation, (C)V(V), in which the segments in parentheses may or may not be present. A syllable cannot begin with two consonant sounds (the digraphs ng and wh represent single consonant sounds), and cannot end in a consonant, although some speakers may occasionally devoice a final vowel. All possible CV combinations are grammatical, though wo, who, wu, and whu occur only in a few loanwords from English such as wuru, "wool" and whutuporo, "football".[74]

As in many other Polynesian languages, e.g., Hawaiian, the rendering of loanwords from English includes representing every English consonant of the loanword (using the native consonant inventory; English has 24 consonants to 10 for Māori) and breaking up consonant clusters. For example, "Presbyterian" has been borrowed as Perehipeteriana; no consonant position in the loanword has been deleted, but /s/ and /b/ have been replaced with /h/ and /p/, respectively.

Stress is typically within the last four vowels of a word, with long vowels and diphthongs counting double. That is, on the last four moras. However, stressed moras are longer than unstressed moras, so the word does not have the precision in Māori that it does in some other languages. It falls preferentially on the first long vowel, on the first diphthong if there is no long vowel (though for some speakers never a final diphthong), and on the first syllable otherwise. Compound words (such as names) may have a stressed syllable in each component word. In long sentences, the final syllable before a pause may have a stress in preference to the normal stressed syllable.

Dialects

Biggs proposed that historically there were two major dialect groups, North Island and South Island, and that South Island Māori is extinct.[76] Biggs has analysed North Island Māori as comprising a western group and an eastern group with the boundary between them running pretty much along the island's north–south axis.[77]

Within these broad divisions regional variations occur, and individual regions show tribal variations. The major differences occur in the pronunciation of words, variation of vocabulary, and idiom. A fluent speaker of Māori has no problem understanding other dialects.

There is no significant variation in grammar between dialects. "Most of the tribal variation in grammar is a matter of preferences: speakers of one area might prefer one grammatical form to another, but are likely on occasion to use the non-preferred form, and at least to recognise and understand it."[78] Vocabulary and pronunciation vary to a greater extent, but this does not pose barriers to communication.

North Island dialects

In the southwest of the island, in the Whanganui and Taranaki regions, the phoneme /h/ is a glottal stop and the phoneme /wh/ is [ʔw]. This difference was the subject of considerable debate during the 1990s and 2000s over the then-proposed change of the name of the city Wanganui to Whanganui.

In Tūhoe and the Eastern Bay of Plenty (northeastern North Island) ng has merged with n. In parts of the Far North, wh has merged with w.

South Island dialects

In the extinct South Island dialects, ng merged with k in many regions. Thus Kāi Tahu and Ngāi Tahu are variations in the name of the same iwi (the latter form is the one used in acts of Parliament). Since 2000, the government has altered the official names of several southern place names to the southern dialect forms by replacing ng with k. New Zealand's highest mountain, known for centuries as Aoraki in southern Māori dialects that merge ng with k, and as Aorangi by other Māori, was later named "Mount Cook", in honour of Captain Cook. Now its sole official name is Aoraki / Mount Cook, which favours the local dialect form. Similarly, the Māori name for Stewart Island, Rakiura, is cognate with the name of the Canterbury town of Rangiora. Likewise, Dunedin's main research library, the Hocken Collections, has the name Uare Taoka o Hākena rather than the northern (standard) Te Whare Taonga o Hākena.[79] Maarire Goodall and George Griffiths say there is also a voicing of k to g – this is why the region of Otago (southern dialect) and the settlement it is named after – Otakou (standard Māori) – vary in spelling (the pronunciation of the latter having changed over time to accommodate the northern spelling).[80] Westland's Waitangitaona River became two distinct rivers after an avulsion, each named in a differing dialect. While the northern river was named the Waitangitāhuna River, the southern river became the Waitakitāhuna-ki-te-Toka, using the more usual southern spelling (ki-te-Toka, "of the south", would be rendered ki-te-Tonga in standard Māori).

The standard Māori r is also found occasionally changed to an l in these southern dialects and the wh to w. These changes are most commonly found in place names, such as Lake Waihola[81] and the nearby coastal settlement of Wangaloa (which would, in standard Māori, be rendered Whangaroa), and Little Akaloa, on Banks Peninsula. Goodall and Griffiths claim that final vowels are given a centralised pronunciation as schwa or that they are elided (pronounced indistinctly or not at all), resulting in such seemingly-bastardised place names as The Kilmog, which in standard Māori would have been rendered Kirimoko, but which in southern dialect would have been pronounced very much as the current name suggests.[82] This same elision is found in numerous other southern placenames, such as the two small settlements called The Kaik (from the term for a fishing village, kainga in standard Māori), near Palmerston and Akaroa, and the early spelling of Lake Wakatipu as Wagadib. In standard Māori, Wakatipu would have been rendered Whakatipua, showing further the elision of a final vowel.

Despite being officially regarded as extinct,[83] many government and educational agencies in Otago and Southland encourage the use of the dialect in signage[84] and official documentation.[85]

Grammar and syntax

Māori has mostly a VSO (verb-subject-object) word order,[86] is analytical and makes extensive use of grammatical particles to indicate grammatical categories of tense, mood, aspect, case, topicalization, among others. The personal pronouns have a distinction in clusivity, singular, dual and plural numbers,[87] and the genitive pronouns have different classes (a class, o class and neutral) according to whether the possession is alienable or the possessor has control of the relationship (a category), or the possession is inalienable or the possessor has no control over the relationship (o category), and a third neutral class that only occurs for singular pronouns and must be followed by a noun.[88]

Bases

Biggs (1998) developed an analysis that the basic unit of Māori speech is the phrase rather than the word.[89] The lexical word forms the "base" of the phrase. "Nouns" include those bases that can take a definite article, but cannot occur as the nucleus of a verbal phrase; for example: ika (fish) or rākau (tree).[90] Plurality is marked by various means, including the definite article (singular te, plural ngā),[91] deictic particles "tērā rākau" (that tree), "ērā rākau" (those trees),[92] possessives "taku whare" (my house), "aku whare" (my houses).[93] A few nouns lengthen a vowel in the plural, such as wahine (woman); wāhine (women).[94] In general, bases used as qualifiers follow the base they qualify, e.g. "matua wahine" (mother, female elder) from "matua" (parent, elder) "wahine" (woman).[95]

Statives serve as bases usable as verbs but not available for passive use, such as ora, alive or tika, correct.[96] Grammars generally refer to them as "stative verbs". When used in sentences, statives require different syntax than other verb-like bases.[97]

Locative bases can follow the locative particle ki (to, towards) directly, such as runga, above, waho, outside, and placenames (ki Tamaki, to Auckland).[98]

Personal bases take the personal article a after ki, such as names of people (ki a Hohepa, to Joseph), personified houses, personal pronouns, wai? who? and Mea, so-and-so.[98]

Particles

Like all other Polynesian languages, Māori has a rich array of particles, which include verbal particles, pronouns, locative particles, articles and possessives.

Verbal particles indicate aspectual, tense related or modal properties of the verb to which they relate to. They include:

- i (past)

- e (non-past)

- kei te (present continuous)

- kua (perfect)

- e ... ana (imperfect, continuous)

- ka (inceptive, future)

- kia (desiderative)

- me (prescriptive)

- kei (warning, "lest")

- ina or ana (punctative-conditional, "if and when")[99]

- kāti (cessative)[100]

- ai (habitual)[101]

Locative particles (prepositions) refer to position in time and/or space, and include:

- ki (to, towards)

- kei (at)

- i (past position)

- hei (future position)[102]

Possessives fall into one of two classes of prepositions marked by a and o, depending on the dominant versus subordinate relationship between possessor and possessed: ngā tamariki a te matua, the children of the parent but te matua o ngā tamariki, the parent of the children.[103]

Articles

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Definite | te | ngā |

| Indefinite | he | |

| Proper | a | |

Definitives include the articles te (singular) and ngā (plural)[104] and the possessive prepositions tā and tō.[88] These also combine with the pronouns.

The indefinite article he is usually positioned at the beginning of the phrase in which it is used. The indefinite article is used when the base is used indefinitely or nominally. These phrases can be identified as an indefinite nominal phrase. The article either can be translated to the English ‘a’ or ‘some’, but the number will not be indicated by he. The indefinite article he when used with mass nouns like water and sand will always mean 'some'.[105]

| He tāne | A man | Some men |

| He kōtiro | A girl | Some girls |

| He kāinga | A village | Some villages |

| He āporo | An apple | Some apples |

The proper article a is used for personal nouns. The personal nouns do not have the definite or indefinite articles on the proper article unless it is an important part of its name. The proper article a always being the phrase with the personal noun.[106]

| Kei hea, a Pita? | Where is Peter? |

| Kei Ākarana, a Pita. | Peter is at Auckland. |

| Kei hea, a Te Rauparaha? | Where is Te Rauparaha? |

| Kei tōku kāinga, a Te Rauparaha. | Te Rauparaha is at my home. |

Determiners

Demonstrative determiners and adverbs

Demonstratives occur after the noun and have a deictic function, and include tēnei, this (near me), tēnā, that (near you), tērā, that (far from us both), and taua, the aforementioned (anaphoric). Other definitives include tēhea? (which?), and tētahi, (a certain). The plural is formed just by dropping the t: tēnei (this), ēnei (these). The related adverbs are nei (here), nā (there, near you), rā (over there, near him).[107]

| Singular | Plural | Adverb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal | tēnei | ēnei | nei |

| Medial | tēnā | ēnā | nā |

| Distal | tērā | ērā | rā |

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

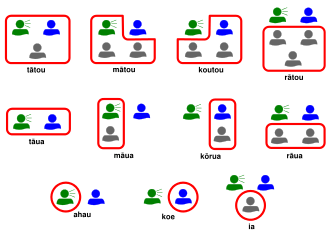

Pronouns have singular, dual and plural number. Different first-person forms in both the dual and the plural are used for groups inclusive or exclusive of the listener.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.INCL | au / ahau | tāua | tātou |

| 1.EXCL | māua | mātou | |

| 2 | koe | kōrua | koutou |

| 3 | ia | rāua | rātou |

- 1

- 2

- 3

Like other Polynesian languages, Māori has three numbers for pronouns and possessives: singular, dual and plural. For example: ia (he/she), rāua (they two), rātou (they, three or more). Māori pronouns and possessives further distinguish exclusive "we" from inclusive "we", second and third. It has the plural pronouns: mātou (we, exc), tātou (we, inc), koutou (you), rātou (they). The language features the dual pronouns: māua (we two, exc), tāua (we two, inc), kōrua (you two), rāua (they two). The difference between exclusive and inclusive lies in the treatment of the person addressed. Mātou refers to the speaker and others but not the person or persons spoken to ("I and some others but not you"), and tātou refers to the speaker, the person or persons spoken to and everyone else ("you, I and others"):[108]

- Tēnā koe: hello (to one person)

- Tēnā kōrua: hello (to two people)

- Tēnā koutou: hello (to more than two people)[109]

Possessive pronouns

The possessive pronouns vary according to person, number, clusivity, and possessive class (a class or o class). Example: tāku pene (my pen), āku pene (my pens). For dual and plural subject pronouns, the possessive form is analytical, by just putting the possessive particle (tā/tō for singular objects or ā/ō for plural objects) before the personal pronouns, e.g. tā tātou karaihe (our class), tō rāua whare (their [dual] house); ā tātou karaihe (our classes). The neuter one must be followed by a noun and only occur for singular first, second and third persons. Taku is my, aku is my (plural, for many possessed items). The plural is made by deleting the initial [t].[88]

| Subject | Object | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Person | Singular | Plural | ||||

| a class | o class | neutral | a class | o class | neutral | ||

| Singular | 1 | tāku | tōku | taku | āku | ōku | aku |

| 2 | tāu | tōu | tō | āu | ōu | ō | |

| 3 | tāna | tōna | tana | āna | ōna | ana | |

Interrogative pronouns

- wai ('who')

- aha ('what')

- hea ('where')

- nō hea ('whence')

- āhea ('when')

- e hia ('how many [things]')

- tokohia ('how many [people]')

- pēhea ('how')

- tēhea ('which'), ēhea ('which [pl.]')

- he aha ... ai ('why [reason]')

- nā te aha ... ai ('why [cause]')[110]

Phrase grammar

A phrase spoken in Māori can be broken up into two parts: the “nucleus” or "head" and “periphery” (modifiers, determiners). The nucleus can be thought of as the meaning and is the centre of the phrase, whereas the periphery is where the grammatical meaning is conveyed and occurs before and/or after the nucleus.[111]

| Periphery | Nucleus | Periphery |

|---|---|---|

| te | whare | nei |

| ki te | whare |

The nucleus whare can be translated as "house", the periphery te is similar to an article "the" and the periphery nei indicates proximity to the speaker. The whole phrase, te whare nei, can then be translated as "this house".[112]

Phrasal particles

A definite and declarative sentence (may be a copulative sentence) begins with the declarative particle ko.[113] If the sentence is topicalized (agent topic, only in non-present sentences) the particle nā begins the sentence (past tense) or the mā (future, imperfective) followed by the agent/subject. In these cases the word order changes to SVO. These agent topicalizing particles can contract with singular personal pronouns and vary according to the possessive classes: nāku can be though of as meaning "as for me" and behave like an emphatic or dative pronoun.[114]

| Past | Future | |

|---|---|---|

| 1S | nāku/nōku | māku/mōku |

| 2S | nāu/nōu | māu/mō |

| 3S | nāna/nōna | māna/mōna |

Case particles

Negation

Forming negative phrases in Māori is quite grammatically complex. There are several different negators which are used under various specific circumstances.[119] The four main negators are as follows:[119]

| Negator | Description |

|---|---|

| kāo | Negative answer to a polar question. |

| kāore/kāhore/kāre/ | The most common verbal negator. |

| kore | A strong negator, equivalent to 'never'. |

| kaua e | Negative imperatives; prohibitive |

| ehara | Negation for copulative phrases, topicalized and equative phrases |

Kīhai and tē are two negators which may be seen in specific dialects or older texts, but are not widely used.[119] The most common negator is kāhore, which may occur in one of four forms, with the kāo form only being used in response to a question.[119] Negative phrases, besides using kāore, also affect the form of verbal particles, as illustrated below.

| Positive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Past | i | i |

| Future | ka | i/e |

| Present | kei te | i te |

| Imperfect | e...ana | |

| Past perfect | kua | kia |

The general usage of kāhore can be seen in the following examples. The subject is usually raised in negative phrases, although this is not obligatory.[120] Each example of a negative phrase is presented with its analogue positive phrase for comparison.

| (1a) | Kāhore | tātou | e | haere | ana | āpōpō |

| NEG | 1PLincl | T/A | move | T/A | tomorrow | |

| 'We are not going tomorrow'[121] | ||||||

| (1b) | E | haere | ana | tātou | āpōpō |

| T/A | move | T/A | 1PLincl | tomorrow | |

| 'We are going tomorrow'[121] | |||||

| (2a) | Kāhore | anō | he | tāngata | kia | tae | mai |

| NEG | yet | a | people | SUBJ | arrive | hither | |

| 'Nobody has arrived yet'[121] | |||||||

| (2b) | Kua | tae | mai | he | tāngata |

| T/A | arrive | hither | a | people | |

| 'Some people have arrived'[121] | |||||

Passive sentences

The passive voice of verbs is made by a suffix to the verb. For example, -ia (or just -a if the verb ends in [i]). The other passive suffixes, some of which are very rare, are: -hanga/-hia/-hina/-ina/-kia/-kina/-mia/-na/-nga/-ngia/-ria/-rina/-tia/-whia/-whina/.[122] The use of the passive suffix -ia is given in this sentence: Kua hangaia te marae e ngā tohunga (The marae has been built by the experts). The active form of this sentence is rendered as: Kua hanga ngā tohunga i te marae (The experts have built the marae). It can seen that the active sentence contains the object marker 'i', that is not present in the passive sentence, while the passive sentence has the agent marker 'e', which is not present in the active sentence.[123]

Polar questions

Polar questions (yes/no questions) can be made by just changing the intonation of the sentence. The answers may be āe (yes) or kāo (no).[124]

Derivational morphology

Although Māori is mostly analytical there are several derivational affixes:

- -anga, -hanga, -ranga, -tanga (-ness, -ity) (the suffix depends on whether the verb takes, respectively, the -ia, -hia, -ria or -tia passive suffixes) (e.g. pōti 'vote', pōtitanga 'election')

- -nga (nominalizer)[125]

- kai- (agentive noun)[126] (e.g. mahi 'work', kaimahi 'worker/employee')

- ma- (adjectives)[127]

- tua- (ordinal numerals)[128] (e.g. tahi 'one', tuatahi 'first/primary')

- whaka- (causative prefix)[129]

Calendar

From missionary times, Māori used adaptations of English names for days of the week and for months of the year. Since about 1990, the Māori Language Commission has promoted new "traditional" sets. Its days of the week have no pre-European equivalent, but reflect the pagan origins of the English names, for example, Hina = moon. The commission based the months of the year on one of the traditional tribal lunar calendars.[130]

|

|

Influence on New Zealand English

New Zealand English has gained many loanwords from Māori, mainly the names of birds, plants, fishes and places. For example, the kiwi, the national bird, takes its name from te reo. "Kia ora" (literally "be healthy") is a widely adopted greeting of Māori origin, with the intended meaning of "hello".[131] It can also mean "thank you", or signify agreement with a speaker at a meeting. The Māori greetings "tēnā koe" (to one person), "tēnā kōrua" (to two people) or "tēnā koutou" (to three or more people) are also widely used, as are farewells such as "haere rā". The Māori phrase "kia kaha", "be strong", is frequently encountered as an indication of moral support for someone starting a stressful undertaking or otherwise in a difficult situation. Many other words such as "whānau" (meaning "family") and "kai" (meaning "food") are also widely understood and used by New Zealanders.

Footnotes

- "Ngā puna kōrero: Where Māori speak te reo – infographic". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "Maori". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Maori". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Waitangi Tribunal. (2011). Ko Aotearoa tēnei: A report into claims concerning New Zealand law and policy affecting Māori culture and identity – Te taumata tuarua. Wellington, New Zealand: Author. Wai No. 262. Retrieved from Archived 2 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Compare: Roy, Eleanor Ainge (28 July 2018). "Google and Disney join rush to cash in as Māori goes mainstream". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

John McCaffery, a language expert at the University of Auckland school of education, says the language is thriving, with other indigenous peoples travelling to New Zealand to learn how Māori has made such a striking comeback. 'It has been really dramatic, the past three years in particular, Māori has gone mainstream,' he said.

- "Māori language speakers". Statistics New Zealand. 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- NZETC: Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century, 1816

- Brownson, Ron (23 December 2010). "Outpost". Staff and friends of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "The Missionary Register". Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. 1831. pp. 54–55. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Higgins, Rawinia; Keane, Basil (1 September 2015). "Te reo Māori – the Māori language". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Maori language". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Māori Language Act 1987 No 176 (as at 30 April 2016), Public Act Contents – New Zealand Legislation". legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- For example: "Maori and the Local Government Act". New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- The New Oxford American Dictionary (Third Edition); Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition; Dictionary.com

- "Official languages". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- "Recognition of Māori Language". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- Definitions of Māori words used in New Zealand English, Peter J. Keegan, last modified 22 April 2019, retrieved 23 September 2019

- Iorns Magallanes, Catherine J. (December 2003). "Dedicated Parliamentary Seats for Indigenous Peoples: Political Representation as an Element of Indigenous Self-Determination". Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law. 10. SSRN 2725610. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Te Ture mō Te Reo Māori 2016 No 17 (as at 01 March 2017), Public Act 7 Right to speak Māori in legal proceedings – New Zealand Legislation". legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1994] 1 NZLR 513

- Dunleavy, Trisha (29 October 2014). "Television – Māori television". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- "New Zealand Gazetteer of Official Geographic Names". Land Information New Zealand.

- K. R. Howe. 'Ideas of Māori origins – 1920s–2000: new understanding', Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 4-Mar-09. URL: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/ideas-of-maori-origins/5

- "Story: Māori education – mātauranga".

- History of the Māori Language, Ministry for Culture and Heritage, updated 10 October 2017, Retrieved 22 September 2019

- Māori MPs, Ministry for Culture and Heritage, updated 15 July 2014, retrieved 22 September 2019

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage, History of the Māori Language

- "Rosina Wiparata: A Legacy of Māori Language Education". The Forever Years. 23 February 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Waitangi Tribunal (2011, p. 440).

- Waitangi Tribunal (2011, p. 470).

- "Controller and Auditor-General". Office of the Auditor-General. Wellington, New Zealand. 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Waitangi Tribunal (2011, p. 471).

- "Waitangi Tribunal". waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Albury, Nathan John (2 October 2015). "Collective (white) memories of Māori language loss (or not)". Language Awareness. 24 (4): 303–315. doi:10.1080/09658416.2015.1111899. ISSN 0965-8416.

- Albury, Nathan John (2 April 2016). "An old problem with new directions: Māori language revitalisation and the policy ideas of youth". Current Issues in Language Planning. 17 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1080/14664208.2016.1147117. ISSN 1466-4208.

- "Harry Potter to be translated into te reo Māori". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Te reo Māori card game Tākaro moves into production after kickstarter campaign

- Mare Haimona-Riki (12 February 2020). "Encouraging te reo Māori through hand-crafted taonga for children". Stuff. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Biggs, Bruce (1994). "Does Māori have a closest relative?" In Sutton (Ed.)(1994), pp. 96–105

- Clark, Ross (1994). "Moriori and Māori: The Linguistic Evidence". In Sutton (Ed.)(1994), pp. 123–135.

- Harlow, Ray (1994). "Māori Dialectology and the Settlement of New Zealand". In Sutton (Ed.)(1994), pp. 106–122.

- The Endeavour Journal of Sir Joseph Banks, 9 October 1769: "we again advancd to the river side with Tupia, who now found that the language of the people was so like his own that he could tolerably well understand them and they him."

- "https://www.radionz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/118294/rapanui-expedition-reveals-similarities-to-te-reo-maori Rapanui expedition reveals similarities to Te Reo Maori]," Radio New Zealand, 16 October 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- "QuickStats About Māori". Statistics New Zealand. 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) (revised 2007) - "Māori Language Issues – Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori". Māori Language Commission. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- Albury, Nathan (2016). "Defining Māori language revitalisation: A project in folk linguistics". Journal of Sociolinguistics. 20 (3): 287–311. doi:10.1111/josl.12183. hdl:10852/58904, p. 301.

- "Census 2016, Language spoken at home by Sex (SA2+)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Aldworth, John (12 May 2012). "Rocks could rock history". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- An underlined k sometimes appears when writing the Southern dialect, to indicate that the /k/ in question corresponds to the ng of the standard language. Both L and G are also encountered in the Southern dialect (qv), though not in standard Māori. Various methods are used to indicate glottal stops when writing the Wanganui dialect.

- Salmond, Anne (1997). Between Worlds: Early Exchanges between Maori and Europeans, 1773–1815. Auckland: Viking.

- Hika, Hongi. "Sample of Writing by Shunghie [Hongi Hika] on board the Active". Marsden Online Archive. University of Otago. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- May, Helen; Kaur, Baljit; Prochner, Larry (2016). Empire, Education, and Indigenous Childhoods: Nineteenth-Century Missionary Infant Schools in Three British Colonies. Routledge. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-317-14434-2. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Stack, James West (1938). Reed, Alfred Hamish (ed.). Early Maoriland adventures of J.W. Stack. p. 217.

- Stowell, Henry M. (November 2008). Maori-English Tutor and Vade Mecum. ISBN 9781443778398. This was the first attempt by a Māori author at a grammar of Māori.

- Apanui, Ngahiwi (11 September 2017). "What's that little line? He aha tēnā paku rārangi?". Stuff. Stuff. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Māori Orthographic Conventions Archived 6 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Māori Language Commission. Accessed on 11 June 2010.

- Keane, Basil (11 March 2010). "Mātauranga hangarau – information technology – Māori language on the internet". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Why Stuff is introducing macrons for te reo Māori words". Stuff. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Seven Sharp - Why are macrons so important in te reo Māori". tvnz.co.nz. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Reporters, Staff. "Official language to receive our best efforts". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Keane, Basil (11 March 2010). "Mātauranga hangarau – information technology - Māori language on the internet". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "Te Wiki o Te Reo Maaori Discovery Trail - Waikato Museum". waikatomuseum.co.nz. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Māori Language Week 2017 - Hamilton City Council". hamilton.govt.nz. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Proposed District Plan (Stage 1) 13 Definitions" (PDF). Waikato District Council. 18 July 2018. p. 28.

- Goldsmith, Paul (13 July 2012). "Taxes - Tax, ideology and international comparisons". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Bauer 1993: 537. Bauer mentions that Biggs 1961 announced a similar finding.

- Bauer 1997: 536. Bauer even raised the possibility of analysing Māori as really having six vowel phonemes, a, ā, e, i, o, u ([a, aː, ɛ, i, ɔ, ʉ]).

- Harlow 1996: 1; Bauer 1997: 534

- /a/ is realised as [ɒ] by many speakers in certain environments, such as between [w] and [k] (Bauer 1993:540) For younger speakers, both are realised as [a].

- Harlow 2006, p. 69.

- Harlow 2006, p. 79.

- Bauer 1997: 532 lists seven allophones (variant pronunciations).

- Williams, H. W. and W. L (1930). First Lessons in Maori. Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. p. 6.

- McLintock, A. H., ed. (1966). "MAORI LANGUAGE – Pronunciation". Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

- Harlow, Ray (2006). Māori, A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1107407626.

- Biggs 1988: 65

- Bauer 1997: xxvi

- Bauer 1993: xxi–xxii

- The Hocken Library contains several early journals and notebooks of early missionaries documenting the vagaries of the southern dialect. Several of them are shown at Blackman, A. "Some Sources for Southern Maori dialect", Hocken Library, 7 July 2001. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Goodall & Griffiths (1980) pp. 46–8.

- Goodall & Griffiths (1980) p. 50: Southern dialect for 'wai' – water, 'hora' – spread out.

- Goodall & Griffiths (1980) p. 45: This hill [The Kilmog]...has a much debated name, but its origins are clear to Kaitahu and the word illustrates several major features of the southern dialect. First we must restore the truncated final vowel (in this case to both parts of the name, 'kilimogo'). Then substitute r for l, k for g, to obtain the northern pronunciation, 'kirimoko'.... Though final vowels existed in Kaitahu dialect, the elision was so nearly complete that pākehā recorders often omitted them entirely.

- As with many "dead" languages, there is a possibility that the southern dialect may be revived, especially with the encouragement mentioned. "The Murihiku language – Mulihig' being probably better expressive of its state in 1844 – lives on in Watkin's vocabulary list and in many muttonbirding terms still in use, and may flourish again in the new climate of Maoritaka." (Natusch, S. (1999) Southward Ho! The Deborah in Quest of a New Edinburgh, 1844. Invercargill, NZ: Craig Printing. ISBN 978-0-908629-16-9 )

- "Approved Māori signage". University of Otago. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Eastern Southland Regional Coastal Plan", from "Regional Coastal Plan for Southland – July 2005 – Chapter 1". See section 1.4, Terminology. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Brief (200) Word Description of the Māori Language, Peter J. Keegan, 2017, Retrieved 16 September 2019

- Biggs 1998: 32-33

- Biggs 1998: 46-48

- Biggs 1998: 3

- Biggs 1998: 54-55

- Bauer 1997: 144-147

- Bauer 1997: 153-154

- Bauer 1997: 394-396

- Bauer 1997: 160

- Biggs 1998: 153

- Biggs 1998: 55

- Biggs 1998: 23-24

- Biggs 1998: 57

- Bauer 1997: 84-100

- Bauer 1997: 447

- Bauer 1997: 98

- Bauer 1997: 30

- Biggs 1998: 42

- Biggs 1998: 7-8

- Biggs 1998: 7

- Biggs 1998: 8-9

- Bauer 1997: 152-154

- Bauer 1997: 261-262

- Greetings - Mihi, MāoriLanguage.net, Retrieved 22 September 2019

- Questions, Kupu o te Rā, Retrieved 22 September 2019

- Biggs 1998: 4

- Biggs 1998: 5

- Biggs 1998: 15-17

- Biggs 1998: 87-89

- Bauer 1997: 181

- Bauer 1997: 175-176

- Bauer 1997: 176-179

- Bauer 1997: 183-184

- Bauer 2001: 139

- Bauer 2001: 141

- Bauer 2001: 140

- Harlow, Ray (2015). A Māori Reference Grammar, Wellington: Huia, p. 113

- Kupu o te Rā: Passive sentences, Retrieved 14 September 2019

- Bauer 1997: 424-427

- Bauer 1997: 517-524

- Bauer 1997: 25-26

- Harlow 2015: 112

- Bauer 1997: 282-283

- Bauer 1997: 44-45

- Māori Orthographic Conventions, Te Taura Whiri i Te Reo Māori (Māori Language Commission), retrieved 23 September 2019

- Swarbrick, Nancy (5 September 2013). "Manners and social behaviour". teara.govt.nz. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

References

- Banks, Sir Joseph. The Endeavour Journal of Sir Joseph Banks, Journal from 25 August 1768 – 12 July 1771. Project Gutenberg. Also available on Wikisource.

- Bauer, Winifred (1993). Maori. Routledge. Series: Routledge descriptive grammars.

- Bauer, Winifred (1997). Reference Grammar of Māori. Auckland: Reed.

- Bauer, Winifred; Evans, Te Kareongawai & Parker, William (2001). Maori. Routledge. Series: Routledge descriptive grammars.

- Biggs, Bruce (1988). Towards the study of Maori dialects. In Ray Harlow and Robin Hooper, eds. VICAL 1: Oceanic languages. Papers from the Fifth International Conference on Austronesian linguistics. Auckland, New Zealand. January 1988, Part I. Auckland: Linguistic Society of New Zealand.

- Biggs, Bruce (1994). "Does Māori have a closest relative?" In Sutton (ed.) (1994), pp. 96–105.

- Biggs, Bruce (1998). Let's Learn Māori. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Clark, Ross (1994). "Moriori and Māori: The Linguistic Evidence" In Sutton (ed.) (1994), pp. 123–135.

- Harlow, Ray (1994). "Māori Dialectology and the Settlement of New Zealand" In Sutton (ed.) (1994), pp. 106–122.

- Harlow, Ray (1996). Maori. LINCOM Europa.

- Goodall, Maarire, & Griffiths, George J. (1980). Maori Dunedin. Dunedin: Otago Heritage Books.

- Sutton, Douglas G., ed. (1994). The Origins of the First New Zealanders. Auckland: Auckland University Press. p. 269. ISBN 1-86940-098-4. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

Further reading

- Benton, R. A. (1984). "Bilingual education and the survival of the Maori language". The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 93(3), 247–266. JSTOR 20705872.

- Benton, R. A. (1988). "The Maori language in New Zealand education". Language, culture and curriculum, 1(2), 75–83. doi:10.1080/07908318809525030.

- Benton, N. (1989). "Education, language decline and language revitalisation: The case of Maori in New Zealand". Language and Education, 3(2), 65–82. doi:10.1080/09500788909541252.

- Benton, R. A. (1997). The Maori Language: Dying or Reviving?. NZCER, Distribution Services, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Gagné, N. (2013). Being Maori in the City: Indigenous Everyday Life in Auckland. University of Toronto Press. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2ttwzt.

- Holmes, J. (1997). "Maori and Pakeha English: Some New Zealand Social Dialect Data". Language in Society, 26(1), 65–101. JSTOR 4168750. doi:10.1017/S0047404500019412.

- Sissons, J. (1993). "The Systematisation of Tradition: Maori Culture as a Strategic Resource". Oceania, 64(2), 97–116. JSTOR 40331380. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1993.tb02457.x.

- Smith, G. H. (2000). "Maori education: Revolution and transformative action". Canadian Journal of Native Education, 24(1), 57.

- Smith, G. H. (2003). "Indigenous struggle for the transformation of education and schooling". Transforming Institutions: Reclaiming Education and Schooling for Indigenous Peoples, 1–14.

- Spolsky, B.. (2003). "Reassessing Māori Regeneration". Language in Society, 32(4), 553–578. JSTOR 4169286. doi:10.1017/S0047404503324042.

- Kendall, Thomas; Lee, Samuel (1820). A Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand. London: R. Watts.

- Tregear, Edward (1891). The Maori-Polynesian comparative dictionary. Wellington: Lyon and Blair.

External links

| Maori edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Ngata Māori–English English–Māori Dictionary from Learning Media; gives several options and shows use in phrases.

- Te Aka Māori-English, English-Māori Dictionary and Index, online version

- Collection of historic Māori newspapers

- Maori Phonology

- maorilanguage.net Learn the basics of Māori Language with video tutorials

- Maori Language Week at NZHistory – includes a history of the Māori language, the Treaty of Waitangi Māori Language claim and 100 words every New Zealander should know

- Huia Publishers, catalogue includes Tirohia Kimihia the world's first Māori monolingual dictionary for learners

- Publications about Māori language from Te Puni Kōkiri, the Ministry of Māori Development

- Te Reo Maori word list A glossary of commonly used Māori words with English translation

- Materials on Maori are included in the open access Arthur Capell collections (AC1 and AC2) held by Paradisec.