English-language vowel changes before historic /l/

In the history of English phonology, there have been many diachronic sound changes affecting vowels, especially involving phonemic splits and mergers. A number of these changes are specific to vowels which occur before /l/.

| History and description of |

| English pronunciation |

|---|

| Historical stages |

| General development |

| Development of vowels |

| Development of consonants |

| Variable features |

| Related topics |

Historical diphthongization before /l/

Diphthongization occurred since Early Modern English in certain -al- and -ol- sequences before coronal or velar consonants, or at the end of a word or morpheme. In these sequences, /al/ became /awl/ and then /ɑul/, while /ɔl/ became /ɔwl/ and then /ɔul/. Both of these merged with existing diphthongs: /ɑu/ as in law and /ɔu/ as in throw.

At the end of a word or morpheme, this produced all, ball, call, fall, gall, hall, mall, small, squall, stall, pall, tall, thrall, wall, control, droll, extol, knoll, poll, roll, scroll, stroll, swollen, toll, and troll. The word shall did not follow this trend, and remains /ʃæl/ today.

Before coronal consonants, this produced Alderney, alter, bald, balderdash, false, falter, halt, malt, palsy, salt, Wald, Walter, bold, cold, fold, gold, hold, molten, mould/mold, old, shoulder (earlier sholder), smolder, told, and wold (in the sense of "tract of land"). As with shall, the word shalt did not follow this trend, and remains /ʃælt/ today.

Before /k/, this produced balk, caulk/calk, chalk, Dundalk, falcon, stalk, talk, walk, folk, Polk, and yolk.

This L-vocalization established a pattern that would influence the spelling pronunciations of some relatively more recent loanwords like Balt, Malta, waltz, Yalta, and polder. It also influenced English spelling reform efforts, explaining the American English mold and molt vs. the traditional mould and moult.

Certain words of more recent origin or coining, however, do not have the change and retain short vowels, including Al, alcohol, bal, Cal, calcium, gal, Hal, mal-, pal, Sal, talc, Val, doll, Moll, and Poll.

Historical L-vocalization

In most circumstances, the changes stopped there. But in -alk and -olk words, the /l/ disappeared entirely in most accents (with the notable exception of Hiberno-English). This change caused /ɑulk/ to become /ɑuk/, and /ɔulk/ to become /ɔuk/. Even outside Ireland, some of these words have more than one pronunciation that retains the /l/ sound, especially in American English where spelling pronunciations caused partial or full reversal of L-vocalization in a handful of cases:

- caulk/calk can be /ˈkɔːlk/ or /ˈkɔːk/.

- falcon can be /ˈfælkən/, /ˈfɔːlkən/ or /ˈfɔːkən/.

- yolk can be /ˈjoʊlk/ or /ˈjoʊk/. yoke as /ˈjoʊk/ is only conditionally homophonous.

Words like fault and vault did not undergo L-vocalization, but rather L-restoration, having previously been L-vocalized independently in Old French and lacking the /l/ in Middle English, but having it restored by Early Modern English. The word falcon existed simultaneously as homonyms fauco(u)n and falcon in Middle English. The word moult/molt never originally had /l/ to begin with, instead deriving from Middle English mout and related etymologically to mutate; the /l/ joined the word intrusively.

The Great Vowel Shift changed the diphthongs to their present pronunciations, with /ɑu/ becoming the monophthong /ɔː/, and /ɔu/ raising to /oʊ/.

The loss of /l/ in words spelt with -alf, -alm, -alve and -olm did not involve L-vocalization in the same sense, but rather the elision of the consonant and usually the compensatory lengthening of the vowel.

Variation between /ɔːl/ and /ɒl/ in salt and similar words

Some words such as salt that traditionally had /ɔːl/ for most RP speakers have alternative pronunciations with /ɒl/ that are used more frequently by younger British English speakers. This variation between /ɔːl/ and /ɒl/ occurs primarily before voiceless consonants, as in salt, false and alter, although it may also occur less commonly in words such as scald where the /l/ comes before a voiced consonant.[1] In England, this laxing before /l/ was traditionally associated with the north but has in recent decades become more widespread, including among younger speakers of RP.

Modern L-vocalization

More extensive L-vocalization is a notable feature of certain dialects of English, including Cockney, Estuary English, New York English, New Zealand English, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia English, in which an /l/ sound occurring at the end of a word or before a consonant is pronounced as some sort of close back vocoid, e.g., [w], [o] or [ʊ]. The resulting sound may not always be rounded. The precise phonetic quality varies. It can be heard occasionally in the dialect of the English East Midlands, where words ending in -old can be pronounced /oʊd/. KM Petyt (1985) noted this feature in the traditional dialect of West Yorkshire but said it has died out.[2] However, in recent decades l-vocalization has been spreading outwards from London and the south east,[3][4] John C Wells argued that it is probable that it will become the standard pronunciation in England over the next one hundred years,[5] an idea which Petyt criticised in a book review.[6]

In Cockney, Estuary English and New Zealand English, l-vocalization can be accompanied by phonemic mergers of vowels before the vocalized /l/, so that real, reel and rill, which are distinct in most dialects of English, are homophones as [ɹɪw].

Graham Shorrocks noted extensive L-vocalisation in the dialect of Bolton, Greater Manchester and commented, "many, perhaps, associate such a quality more with Southern dialects, than with Lancashire/Greater Manchester."[7]

In the accent of Bristol, syllabic /l/ can be vocalized to /o/, resulting in pronunciations like /ˈbɒto/ (for bottle). By hypercorrection, however, some words originally ending in /o/ were given an /l/: the original name of the town was Bristow, but this has been altered by hypercorrection to Bristol.[8]

African-American English (AAE) dialects may have L-vocalization as well. However, in these dialects, it may be omitted altogether (e.g. fool becomes [fuː]. Some English speakers from San Francisco - particularly those of Asian ancestry - also vocalize or omit /l/.[9]

Salary–celery merger

The salary–celery merger is a conditioned merger of /æ/ (as in bat) and /ɛ/ (as in bet) when they occur before /l/, thus making salary and celery homophones.[10][11][12][13] The merger is not well studied. It is referred to in various sociolinguistic publications, but usually only as a small section of the larger change undergone by vowels preceding /l/ in articles about l-vocalization.

This merger has been detected in the English spoken in New Zealand and in parts of the Australian state of Victoria, including the capital Melbourne.[14][15] In varieties with the merger, salary and celery are both pronounced /sæləri/ (Cox & Palethorpe, 2003).

The study presented by Cox and Palethorpe at a 2003 conference tested just one group of speakers from Victoria: 13 fifteen-year-old girls from a Catholic girls' school in Wangaratta. Their pronunciations were compared with those of school girl groups in the towns of Temora, Junee and Wagga Wagga in New South Wales. In the study conducted by Cox and Palethorpe, the group in Wangaratta exhibited the merger while speakers in Temora, Junee and Wagga Wagga did not.

Dr. Deborah Loakes from Melbourne University has suggested that the salary-celery merger is restricted to Melbourne and southern Victoria, not being found in northern border towns such as Albury-Wodonga or Mildura.[14]

In the 2003 study Cox and Palethorpe note that the merger appears to only involve lowering of /e/ before /l/, with the reverse not occurring, stating that "There is no evidence in this data of raised /æ/ before /l/ as in 'Elbert' for 'Albert', a phenomenon that has been popularly suggested for Victorians."[11]

Horsfield (2001) investigates the effects of postvocalic /l/ on the preceding vowels in New Zealand English; her investigation covers all of the New Zealand English vowels and is not specifically tailored to studying mergers and neutralizations, but rather the broader change that occurs across the vowels. She has suggested that further research involving minimal pairs like telly and tally, celery and salary should be done before any firm conclusions are drawn.

A pilot study of the merger was done, which yielded perception and production data from a few New Zealand speakers. The results of the pilot survey suggested that although the merger was not found in the speech of all participants, those who produced a distinction between /æl/ and /el/ also accurately perceived a difference between them; those who merged /æl/ and /el/ were less able to accurately perceive the distinction. The finding has been interesting to some linguists because it concurs with the recent understanding that losing a distinction between two sounds involves losing the ability to produce it as well as to perceive it (Gordon 2002). However, due to the very small number of people participating in the study the results are not conclusive.

| /æl/ | /ɛl/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allan | Ellen | ælən | |

| bally | belly | bæli | |

| dally | Delhi | dæli | |

| dally | deli | dæli | |

| fallow | fellow | fæloʊ | |

| Hal | hell | hæl | |

| mallow | mellow | mæloʊ | |

| Sal | cel | sæl | |

| Sal | cell | sæl | |

| Sal | sell | sæl | |

| salary | celery | sæləri | |

| shall | shell | ʃæl |

Fill–feel merger

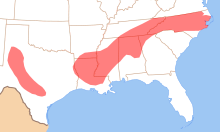

The fill–feel merger is a conditioned merger of the vowels /ɪ/ and /iː/ before /l/ that occurs in some accents. In Europe, it is commonly found in Estuary English. Otherwise it is typical of certain accents of American English. The heaviest concentration of the merger is found in, but not necessarily confined to Southern American English: in North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, northern Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana (but not New Orleans), and west-central Texas (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006: 69-73). This merger, like many other features of Southern American English, can also be found in AAE.

| /ɪl/ | /iːl/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| dill | deal | dɪl | |

| fill | feel | fɪl | |

| filled | field | fɪld | |

| hill | heal | hɪl | |

| hill | heel | hɪl | |

| hill | he'll | hɪl | |

| ill | eel | ɪl | |

| Jill | geal | dʒɪl | |

| kill | keel | kɪl | |

| mill | meal | mɪl | |

| nil | kneel | nɪl | |

| nil | Neil | nɪl | |

| Phil | feel | fɪl | |

| pill | peel | pɪl | |

| rill | real | rɪl | |

| rill | reel | rɪl | |

| shill | she'll | ʃɪl | |

| shilled | shield | ʃɪld | |

| sill | ceil | sɪl | |

| sill | seal | sɪl | |

| silly | Seely | sɪli | |

| still | steal | stɪl | |

| still | steel | stɪl | |

| till | teal | tɪl | |

| will | we'll | wɪl | |

| will | wheel | wɪl | With wine-whine merger. |

| willed | wheeled | wɪld | With wine-whine merger. |

| willed | wield | wɪld |

Fell–fail merger

The same two regions show a closely related merger, namely the fell–fail merger of /ɛ/ and /eɪ/ before /l/ that occurs in some varieties of Southern American English making fell and fail homophones. In addition to North Carolina and Texas, these mergers are found sporadically in other Southern states and in the Midwest and West.[17][18]

| /ɛl/ | /eɪl/ | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| bell | bail | bɛl | |

| bell | bale | bɛl | |

| belle | bail | bɛl | |

| belle | bale | bɛl | |

| cell, cel | sail | sɛl | |

| cell, cel | sale | sɛl | |

| dell | dale | dɛl | |

| fell | fail | fɛl | |

| gel | gaol, jail | dʒɛl | |

| held | hailed | hɛld | |

| hell | hail | hɛl | |

| hell | hale | hɛl | |

| knell | nail | nɛl | |

| Mel | mɛl | ||

| Mel | male | mɛl | |

| meld | mailed | mɛld | |

| Nell | nail | nɛl | |

| quell | quail | kwɛl | |

| sell | sail | sɛl | |

| sell | sale | sɛl | |

| shell | shale | ʃɛl | |

| swell | swale | swɛl | |

| tell | tail | tɛl | |

| tell | tale | tɛl | |

| weld | wailed | wɛld | |

| well | wail | wɛl | |

| well | wale | wɛl | |

| wells | wales | wɛlz | |

| wells | Wales | wɛlz | |

| well | whale | wɛl | With wine-whine merger. |

| wells | wails | wɛlz | |

| wells | whales | wɛlz | With wine-whine merger. |

| yell | Yale | jɛl |

Full–fool merger

The full–fool merger is a conditioned merger of /ʊ/ and /uː/ before /l/, making pairs like pull/pool and full/fool homophones. The main concentration of the pull–pool merger is in Western Pennsylvania English, centered around Pittsburgh. The merger is less consistently but still noticeably present in some speakers of surrounding Midland American English.[19] The Atlas of North American English also reports this merger, or near-merger, scattered sporadically throughout Western American English, with particular prevalence in some speakers of urban Utahn, Californian, and New Mexican English.[20] Accents with L-vocalization, such as New Zealand English, Estuary English and Cockney, may also have the full–fool merger in most cases, but when a suffix beginning with a vowel is appended, the distinction returns: Hence 'pull' and 'pool' are [pʊo], but 'pulling' is /ˈpʊlɪŋ/ whereas 'pooling' remains /ˈpuːlɪŋ/.[21]

The fill–feel merger and full–fool merger are not unified in American English; they are found in different parts of the country, and very few people show both mergers.[22]

Hull–hole merger

The hull–hole merger is a conditioned merger of /ʌ/ and /oʊ/ before /l/ occurring for some speakers of English English with l-vocalization. As a result, "hull" and "hole" are homophones as [hɔʊ]. The merger is also mentioned by Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006: 72) as a merger before /l/ in North American English that might require further study.

Doll–dole merger

The doll–dole merger is a conditioned merger, for some Londoners, of /ɒ/ and /əʊ/ before word-final /l/. As a result, doll and dole may become homophones.[23] If the /l/ is morpheme-final, as in doll-dole, the underlying vowel is still distinguished in derived forms such as dolling/doling.[23]

Where the /l/ is not word-final, however, the distinction is not recoverable. That may lead to sold having the same vowel sound as solve as well as hypercorrections such as /səʊlv/ for solve (RP /sɒlv/).[23] There do not appear to be any minimal pairs in this environment since RP /ɒl/ and /əʊl/ are in more-or-less complementary distribution in stressed syllables, with /ɒl/ before /f/ and /v/ (e.g. golf, dolphin, solve, revolve) and /əʊl/ elsewhere (e.g. bolt, polka, gold, soldier, holster).

Fool-fall merger

For some English speakers in the UK, the vowels of goose and thought may be merged before dark syllable-final /l/.[24] This neutralization has been found to exist for clusters of speakers in the southern UK, especially for speakers from areas of the south coast and the Greater London area.[25]

Goat split

The goat split is a process that has affected London dialects and Estuary English.[26][27] In the first phase of the split, the diphthong of goat /əʊ/ developed an allophone [ɒʊ] before "dark" (nonprevocalic) /l/. Thus goal no longer had the same vowel as goat ([ɡɒʊɫ] vs. [ɡəʊʔ]).[26] In the second phase, the diphthong [ɒʊ] spread to other forms of affected words. For example, the realization of rolling changed from [ˈɹəʊlɪŋ] to [ˈɹɒʊlɪŋ] on the model of roll [ɹɒʊɫ]. This led to the creation of a minimal pair for some speakers: wholly /ˈhɒʊli/ vs. holy /ˈhəʊli/ and thus to phonemicization of the split. The change from /əʊ/ to /ɒʊ/ in derived forms is not fully consistent; for instance, in cockney, polar is pronounced with the /əʊ/ of goat even though it is derived from pole /ˈpɒʊl/.

In broad Cockney, the phonetic difference between the two phonemes may be rather small and they may be distinguished by nothing more than the openness of the first element, so that goat is pronounced [ɡɐɤʔ] whereas goal is pronounced [ɡaɤ].[26]

Vile–vial merger

The vile–vial merger is where the words in the vile set ending with /-ˈaɪl/ (bile, file, guile, I'll, Kyle, Lyle, mile, Nile, pile, rile, smile, stile, style, tile, vile, while, wile) rhyme with words in the vial set ending with /-ˈaɪəl/ (decrial, denial, dial, espial, Niall, phial, trial, vial, viol).[28] This merger involves the dephonemicization of schwa that occurs after a vowel and before /l/, causing the vowel-/l/ sequence to be pronounced as either one or two syllables.

This merger may also be encountered with other vowel rhymes too, including:

- /-ˈeɪl/ (gaol, sale, tail, etc.) and /-ˈeɪəl/ (betrayal, Jael), usually skewing towards two syllables.

- /-ˈɔɪl/ (coil, soil, etc.) and /-ˈɔɪəl/ (loyal, royal), usually skewing towards two syllables.

- /-ˈiːl/ (ceil, feel, steal, etc.) and /-ˈiːəl/ (real), usually skewing towards two syllables.

- /-ˈɔːl/ (all, drawl, haul, etc.) and /-ˈɔːəl/ (withdrawal), usually skewing towards one syllable.

- /-ˈoʊl/ (bowl, coal, hole, roll, soul, etc.) and /-ˈoʊəl/ (Joel, Noel), usually skewing towards one syllable.

- /-ˈuːl/ (cool, ghoul, mewl, rule, you'll, etc.) and /-ˈuːəl/ (cruel, dual, duel, fuel, gruel, jewel), usually skewing towards one syllable.

- /-ˈaʊl/ (owl, scowl, etc.) and /-ˈaʊəl/ (bowel, dowel, Powell, towel, trowel, vowel), inconsistently skewing towards either one or two syllables. Some words may wander across this boundary even in some non-merging accents, such as owl with /-ˈaʊəl/, and bowel with /-ˈaʊl/.

- In some rhotic accents, /-ˈɜrl/ (girl, hurl, pearl, etc.) and /-ˈɜrəl/ (referral), usually skewing towards two syllables. This historically happened to the word squirrel, which was previously /ˈskwɪrəl/ (and still is in certain accents), but it actually became one syllable /ˈskwɜrl/ in General American today. But some accents with one-syllable squirrel later broke it again into two syllables, but as /ˈskwɜrəl/.

- In some rhotic father–bother merged accents, /-ˈɑrl/ (Carl, marl, etc.) and /-ˈɑrəl/ (coral, moral), usually skewing towards two syllables.

For many speakers, the vowels in cake, meet, vote and moot can become centering diphthongs before /l/, leading to pronunciations like [teəl], [tiəl], [toəl] and [tuəl] for tail, teal, toll and tool.

Merger of non-prevocalic /ʊl/, /ʉːl/, /əl/, /oːl/ with /oː/

In cockney, non-prevocalic /ʊl/ (as in bull), /ʉːl/ (as in pool), /əl/ (as in bottle) and /oːl/ (as in call) can all merge with the /oː/ of thought, thus reintroducing the phoneme in the word-final position where, acccording to one analysis, only /ɔə/ can occur (see thought split): /ˈboː, ˈpoː, ˈbɒtoː, ˈkoː/. The last three words can contrast with the open variety of THOUGHT (which is not distinct from NORTH and FORCE and often also encompasses CURE - see cure-force merger), as in core, bore and paw: /ˈkɔə, ˈbɔə, ˈpɔə/, also in pairs such as stalled /ˈstoːd/ - stored /ˈstɔəd/.

The merger of /əl/, /oːl/ and /oː/ is the most usual and leads to musical being homophonous with music hall as /ˈmjʉːzɪkoː/. Speakers of cockney are usually ready to treat both syllables of awful as rhyming: /ˈoːfoː/.[29]

The merger of /oːl/ with /oː/ has been reported to occur in New Zealand English, which does not feature the thought split (leading to a larger number of potential homophones).[30]

In the following list, the only homophonous pairs that are included are those involving /oː/ and /oːl/. As the merger is restricted to non-rhotic accents with close THOUGHT, /oː/ in the fifth and sixth collumns is assumed to cover not only THOUGHT but also NORTH and FORCE. In the case of cockney, the sixth column does not participate in the merger.

| /ʊl/ | /ʉːl/ | /əl/ | /oːl/ | Morpheme-internal /oː/ | Morpheme-final /oː/ (Cockney /ɔə/) | IPA | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | all | N/A | awe | ˈoː | |||

| N/A | all | N/A | or | ˈoː | With the strong form of or. | ||

| N/A | all | N/A | ore | ˈoː | |||

| N/A | alls | ores | ˈoːz | ||||

| N/A | alls | ors | ˈoːz | ||||

| N/A | alls | Hawes | whores | ˈoːz | With h-dropping. | ||

| N/A | Alt | hawk | ˈoːʔ | With h-dropping and glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | Alt | hork | ˈoːʔ | With h-dropping and glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | Alt | ort | ˈoːt | ||||

| N/A | Alt | orc | ˈoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | Auld | ord | awed | ˈoːd | |||

| bull | Boole | N/A | ball | N/A | boar | ˈboː | |

| bull | Boole | N/A | ball | N/A | bore | ˈboː | |

| bulled | N/A | bald | bawd | bored | ˈboːd | ||

| bulled | N/A | bald | board | bored | ˈboːd | ||

| bulled | N/A | balled | bawd | bored | ˈboːd | ||

| bulled | N/A | balled | board | bored | ˈboːd | ||

| bulls | Booles | N/A | balls | boars | ˈboːz | ||

| bulls | Booles | N/A | balls | bores | ˈboːz | ||

| cool | N/A | call | N/A | core | ˈkoː | ||

| coolled | N/A | called | cord | ˈkoːd | |||

| cools | N/A | calls | cause | cores | ˈkoːz | ||

| drool | N/A | drawl | N/A | draw | ˈdroː | ||

| drooled | N/A | drawled | drawed | ˈdroːd | |||

| drools | N/A | drawls | draws | ˈdroːz | |||

| N/A | false | force | ˈfoːs | ||||

| N/A | fault | fork | ˈfoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | fault | fort | ˈfoːt | ||||

| N/A | fault | fought | ˈfoːt | ||||

| N/A | fault | thought | ˈfoːt | With th-fronting. | |||

| N/A | faults | forks | ˈfoːʔs | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | faults | forts | ˈfoːts | ||||

| N/A | faults | thoughts | ˈfoːts | With th-fronting. | |||

| full | fool | N/A | fall | N/A | for | ˈfoː | With the strong form of for |

| full | fool | N/A | fall | N/A | fore | ˈfoː | |

| full | fool | N/A | fall | N/A | four | ˈfoː | |

| full | fool | N/A | fall | N/A | thaw | ˈfoː | With th-fronting. |

| fulled | foolled | N/A | ford | ˈfoːd | |||

| fulled | foolled | N/A | ford | thawed | ˈfoːd | With th-fronting. | |

| fulls | fools | N/A | falls | fours | ˈfoːz | ||

| N/A | Galt | gork | ˈɡoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | Galt | gorp | ˈɡoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /p/. | |||

| N/A | gault | gorp | ˈɡoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /p/. | |||

| N/A | hall | N/A | whore | ˈhoː | |||

| N/A | halls | Hawes | whores | ˈhoːz | |||

| N/A | halt | hawk | ˈoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. Normally with h-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halt | hork | ˈoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. Normally with h-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halt | ort | ˈoːt | With h-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halt | orc | ˈoːʔ | With h-dropping and glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | halting | Hawking | ˈoːʔɪn | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. Normally with h-dropping and g-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halting | horking | ˈoːʔɪn | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. Normally with h-dropping and g-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halts | hawks | ˈoːʔs | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. Normally with h-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halts | horks | ˈoːʔs | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. Normally with h-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halts | orts | ˈoːts | With h-dropping. | |||

| N/A | halts | orcs | ˈoːʔs | With h-dropping and glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | hard call | N/A | hardcore | ˈhɑːdkoː | Homophony depends on where the stress falls in hard call. | ||

| help full | help fool | helpful | help fall | N/A | help for | ˈhɛopfoː | With emphatic stress on help in the phrases and with the strong form of for (as in What do you need my help for?) |

| help full | help fool | helpful | help fall | N/A | help four | ˈhɛopfoː | With emphatic stress on help in the phrases. |

| in stool | N/A | install | N/A | in store | ɪnˈstoː | ||

| in stool | N/A | install | N/A | in-store | ɪnˈstoː | ||

| in stools | N/A | installs | in stores | ɪnˈstoːz | |||

| N/A | mall | N/A | more | ˈmoː | |||

| N/A | malt | mort | ˈmoːt | ||||

| musical | music hall | N/A | ˈmjʉːzɪkoː | With h-dropping. | |||

| pull | pool | N/A | Paul | N/A | paw | ˈpoː | |

| pull | pool | N/A | Paul | N/A | poor | ˈpoː | With the cure-force merger. |

| pull | pool | N/A | Paul | N/A | pore | ˈpoː | |

| pull | pool | N/A | Paul | N/A | pour | ˈpoː | With the cure-force merger. |

| pulled | pooled | N/A | pawed | ˈpoːd | |||

| pulled | pooled | N/A | poured | ˈpoːd | With the cure-force merger. | ||

| pulls | pools | N/A | Pauls | pause | paws | ˈpoːz | |

| pulls | pools | N/A | Pauls | pause | pores | ˈpoːz | |

| pulls | pools | N/A | Pauls | pause | pours | ˈpoːz | With the cure-force merger. |

| pulls | pools | N/A | Paul's | pause | paws | ˈpoːz | |

| pulls | pools | N/A | Paul's | pause | pores | ˈpoːz | |

| recool | N/A | recall | N/A | riːˈkoː | Recall is also pronounced with initial /rɪ-/ and /rə-/ | ||

| recooled | N/A | recalled | record (v.) | riːˈkoːd | Recalled and record are also pronounced with initial /rɪ-/ and /rə-/ | ||

| N/A | salt | Sauk | ˈsoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. In contemporary RP salt often has /ɒl/: /ˈsɒlt/ | |||

| N/A | salt | sort | ˈsoːt | In contemporary RP salt often has /ɒl/: /ˈsɒlt/ | |||

| N/A | salt | sought | ˈsoːt | In contemporary RP salt often has /ɒl/: /ˈsɒlt/ | |||

| N/A | salted | sorted | ˈsoːtɪd | In contemporary RP salted often has /ɒl/: /ˈsɒltɪd/ | |||

| N/A | salting | sorting | ˈsoːtɪŋ | In contemporary RP salting often has /ɒl/: /ˈsɒltɪŋ/ | |||

| N/A | salts | Sauks | ˈsoːʔs | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. In contemporary RP salts often has /ɒl/: /ˈsɒlts/ | |||

| N/A | salts | sorts | ˈsoːts | In contemporary RP salts often has /ɒl/: /ˈsɒlts/ | |||

| N/A | Saul | N/A | saw | ˈsoː | |||

| N/A | Saul | N/A | sore | ˈsoː | |||

| school | N/A | N/A | score | ˈskoː | |||

| schooled | N/A | scald | scored | ˈskoːd | |||

| stool | N/A | stall | N/A | store | ˈstoː | ||

| stooled | N/A | stalled | stored | ˈstoːd | |||

| stools | N/A | stalls | stores | ˈstoːz | |||

| tool | N/A | tall | N/A | tore | ˈtoː | ||

| tool | N/A | tall | N/A | tour | ˈtoː | With the cure-force merger. | |

| N/A | true-false | true force | ˌtrʉːˈfoːs | ||||

| will full | will fool | willful | will fall | N/A | ˈwɪofoː | With emphatic stress on will in the phrases. | |

| wolf | N/A | wharf | ˈwoːf | ||||

| wolf | N/A | Wharfe | ˈwoːf | ||||

| wolf | N/A | Whorf | ˈwoːf | ||||

| wool | N/A | wall | N/A | war | ˈwoː | ||

| N/A | Walt | walk | ˈwoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /k/. | |||

| N/A | Walt | warp | ˈwoːʔ | With glottal replacement of both /t/ and /p/. | |||

| N/A | Walt | wart | ˈwoːt | ||||

| wools | N/A | walls | wars | ˈwoːz |

There is a large amount of potential homophones involving adjectives with the suffix -able and phrases consisting of a related verb, the indefinite article and the nouns bull, ball and boar. However, they require not only emphatically stressing the verb but also no glottal stop before the indefinite article (e.g. afford a bull/ball/boar cannot be pronounced as [əˌfoːdəˈboː], [əˌfoːdʔəˈboː] nor [əˈfoːdʔəboː]), which makes the homophony between the phrases and the adjectives ending in -able less likely than the homophony between the phrases themselves for speakers who have the merger. Again, phrases involving the noun boar are distinct for speakers with the thought split regardless of stress: [əˌfoːdəˈbɔə, əˌfoːdʔəˈbɔə, əˈfoːdʔəbɔə, əˈfoːdəbɔə] ('afford a boar').

Other mergers

Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006:73) mention four mergers before /l/ that may be under way in some accents of North American English, and which require more study:[31]

- /ʊl/ and /oʊl/ (bull vs bowl)

- /ʌl/ and /ɔːl/ (hull vs hall)

- /ʊl/ and /ʌl/ (bull vs hull) (effectively undoing the foot-strut split before /l/)

- /ʌl/ and /oʊl/ (hull vs bowl)

See also

- Phonological history of the English language

- Phonological history of English vowels

- English-language vowel changes before historic r

References

- Wells, John (2010). "scolding water" (February 16). John Wells’s phonetic blog. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- KM Petyt, Dialect & Accent in Industrial West Yorkshire, John Benjamins Publishing Company, page 219

- Asher, R.E., Simpson, J.M.Y. (1993). The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Pergamon. p. 4043. ISBN 978-0080359434

- Kortmann, Bernd et al. (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 196. ISBN 978-3110175325.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22919-7. (vol. 1), ISBN 0-521-24224-X (vol. 2), ISBN 0-521-24225-8 (vol. 3).: Vol. 1, p. 259

- Petyt, KM (1982). "Reviews: JC Wells: Accents of English". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge. 12 (2): 104–112. doi:10.1017/S0025100300002516. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Shorrocks, Graham (1999). A Grammar of the Dialect of the Bolton Area. Pt. 2: Morphology and syntax. Bamberger Beiträge zur englischen Sprachwissenschaft; Bd. 42. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 255. ISBN 3-631-34661-1. (based on the author's thesis (Ph. D.)--University of Sheffield, 1981)

- Harper, Douglas. "Bristol". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- L Hall-Lew & RL Starr, Beyond the 2nd generation: English use among Chinese Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area, English Today: The International Review of the English Language, Vol. 26, Issue 3, pp. 12-19.

- Cox, F.; Palethorpe, S. (2001). "The Changing Face of Australian Vowels". In Blair, D.B.; Collins, P (eds.). Varieties of English Around the World: English in Australia. John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam. pp. 17–44.

- Cox, F. M.; Palethorpe, S. (2003). "The border effect: Vowel differences across the NSW–Victorian Border" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2003 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society: 1–14. Note: online version is PDF.

- Palethorpe, S. and Cox, F. M. (2003) . Poster presented at the International Seminar on Speech Production, December 2003, Sydney. Note: online version is PDF.

- Ingram, John. Norfolk Island-Pitcairn English (Pitkern Norfolk), University of Queensland, 2006

- Are Melburnians mangling the language?

- The /el/-/æl/ Sound Change in Australian English: A Preliminary Perception Experiment, Deborah Loakes, John Hajek and Janet Fletcher, University of Melbourne

- "Map 4". Ling.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- "Map 7". Ling.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20061028164228/http://www.ling.upenn.edu/phonoatlas/Atlas_chapters/Ch9/Ch9.html

- "Map 5". Ling.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:70)

- "Transcribing Estuary English". Phon.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- "Map 6". Ling.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- Wells: 317

- Lindsey, Geoff. "People fool in love (extended mix)". Speech Talk Blog. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- MacKenzie, Laurel; Bailey, George; Turton, Danielle (2016). "Who pronounces 'fool' and 'fall' the same?". Our Dialects: Mapping variation in English in the UK. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Wells, p. 312-313

- Altendorf, Ulrike (2003). Estuary English: Levelling at the Interface of RP and South-Eastern British English. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. p. 34. ISBN 3-8233-6022-1.

- According to Dictionary.com, dial, trial and vial all specify variable /-ˈaɪəl/ or /-ˈaɪl/ pronunciations, while words like bile and style only specify /-ˈaɪl/ pronunciations.

- Wells (1982).

- Gordon, Elizabeth; Maclagan, Margaret (2004), "Regional and social differences in New Zealand: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 611–612, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)