Racism in the Soviet Union

Soviet leaders and authorities officially condemned nationalism and proclaimed internationalism, including the right of nations and peoples to self-determination.[1][2] In practice however, they conducted policies which were the complete opposite of internationalism and these policies included but were not limited to: the systematic large-scale cleansing of ethnic minorities, political repression and various forms of ethnic and social discrimination, including state-enforced antisemitism, Tatarophobia, and Polonophobia.

Several distinct ethnic-linguistic groups, including the Balkars, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, Ingush, Karachays, Kalmyks, Koreans, and Meskhetian Turks were collectively deported to Siberia and Central Asia where they were designated "special settlers", meaning that they were officially second-class citizens with few rights and were confined within a small perimeter. Steven Rosefielde and Norman Naimark put overall deaths closer to some 1 to 1.5 million as a result of the deportations – of those deaths, the deportation of the Crimean Tatars and the deportation of the Chechens and Ingush were recognized as genocides by Ukraine and three other countries as well as the European Parliament respectively.[3][4][5] The Holodomor famine has been frequently described as a deliberate "Terror-Famine" campaign organized by the Soviet authorities against the Ukrainian population.

Eastern Europeans

Ukrainians

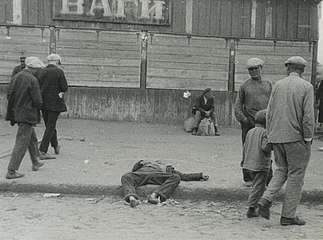

During a famine known as the Holodomor, which is also known as the "Terror-Famine in Ukraine" and "Famine-Genocide in Ukraine",[6][7][8] millions of citizens of the Ukrainian SSR, the majority of whom were ethnic Ukrainians, died of starvation in a peacetime catastrophe unprecedented in the history of Ukraine.[9] Since 2006, the Holodomor has been recognized by the independent Ukraine[10] and 14 other countries as a genocide of the Ukrainian people carried out by the Soviet Union.[11] The reasons of the famine is the subject of intense scholarly and political debate. Some historians claim the famine was purposely engineered by the Soviet authorities to attack Ukrainian nationalism, while others view it as an unintended consequence of the economic problems associated with radical economic changes implemented during Soviet industrialization.[12]

Although famine, caused by collectivization, raged in many parts of the Soviet Union in 1932, special and particularly lethal policies, described by Yale historian Timothy Snyder in his book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (2010), were adopted in and largely limited to Ukraine at the end of 1932 and 1933.[13] Snyder lists seven crucial policies that applied only, or mainly, to Soviet Ukraine. He states: "Each of them may seem like an anodyne administrative measure, and each of them was certainly presented as such at the time, and yet each had to kill":[13]

- From 18 November 1932 peasants from Ukraine were required to return extra grain they had previously earned for meeting their targets. State police and party brigades were sent into these regions to root out any food they could find.

- Two days later, a law was passed forcing peasants who could not meet their grain quotas to surrender any livestock they had.

- Eight days later, collective farms that failed to meet their quotas were placed on "blacklists" in which they were forced to surrender 15 times their quota. These farms were picked apart for any possible food by party activists. Blacklisted communes had no right to trade or to receive deliveries of any kind, and became death zones.

- On 5 December 1932, Stalin's security chief presented the justification for terrorizing Ukrainian party officials to collect the grain. It was considered treason if anyone refused to do their part in grain requisitions for the state.

- In November 1932 Ukraine was required to provide 1/3 of the grain collection of the entire Soviet Union. As Lazar Kaganovich put it, the Soviet state would fight "ferociously" to fulfill the plan.

- In January 1933 Ukraine's borders were sealed in order to prevent Ukrainian peasants from fleeing to other republics. By the end of February 1933 approximately 190,000 Ukrainian peasants had been caught trying to flee Ukraine and were forced to return to their villages to starve.

- The collection of grain continued even after the annual requisition target for 1932 was met in late January 1933.[13]

In the years of 1944 to 1946, the Ukrainian population of the Soviet Union and Poland were to be voluntarily relocated, but eventually forceful tactics prevailed. Within the course of a single year, from July 1945 to July 1946, some 400,000 Ukrainians and Rusyns were uprooted and deported by force.[14]

Crimean Tatars

The forcible deportation of the Crimean Tatars from Crimea was ordered by Stalin as a form of ethnic cleansing of the region and collective punishment for alleged collaboration with the Nazi occupation regime in Taurida Subdistrict during 1942–1943. A total of more than 230,000 people were deported, mostly to the Uzbek SSR. This included the entire ethnic Crimean Tatar population, at the time about a fifth of the total population of the Crimean Peninsula, as well as ethnic Greeks and Bulgarians. A large number of deportees (more than 100,000 according to a 1960s survey by Crimean Tatar activists) died from starvation or disease as a direct result of deportation. It is considered to be a case of illegal ethnic cleansing by the Russian government and genocide by Ukraine. During and after the deportation, the Soviet government dispatched spokespersons to spread anti-Tatar propaganda throughout destinations of deportation and Crimea, slandering them as bandits and depicting them as barbarians,[15] going so far as to hold a conference dedicated to remembering the "struggle against Tatar bourgeoisie nationalists". Depicting the Crimean Tatar people as "Mongols" with no historical connection to Crimea in official state propaganda became an important aspect of attempts to legitimize the deportation of Crimean Tatars and the slavic settler-colonialism of the peninsula. While most deported ethnic groups were allowed to return to their homelands in the 1950s, a vast majority of Crimean Tatars were forced to remain in exile under the household registration system until 1989. During that period, Slavs from Ukraine and Russia were encouraged to repopulate the peninsula and all but four villages with Tatar names were given Slavic names in the Soviet detatarization campaign.[16][17][18][19]

Cossacks

The Soviet Union enacted a campaign of decossackization to end the existence of Cossacks, a social and ethnic group in Russia. Many authors characterize decossackization as genocide of the Cossacks.[20][21][22][23][24]

Estonians

As the Soviet Union had occupied Estonia in 1940 and retaken it from Nazi Germany again in 1944, tens of thousands of Estonia's citizens underwent deportation in the 1940s. Deportations were predominantly to Siberia and Kazakh SSR by means of railroad cattle cars, without prior announcement, while the deported were given few night hours at best to pack their belongings and separated from their families, usually also sent to the east. The procedure was established by the Serov Instructions. Estonians residing in Leningrad Oblast had already been subjected to deportation since 1935.[25][26] The major deportations included the June deportation and Operation Priboi. Outside the main waves, individuals and families were continually deported on smaller scale from the start of the first occupation in 1940 up to the Khrushchev Thaw of 1956 when destalinisation led Soviet Union to switch its tactic of terror from mass repressions to individual repressions. The Soviet deportations only stopped for three years in 1941–1944 when Estonia was occupied by Nazi Germany.

On July 27, 1950 diplomats-in-exile of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania appealed to the United States to support a United Nations investigation of "genocidal mass deportations" they said were being carried out in their countries by the Soviet Union.[27] Stalin's deportation of peoples was later criticized in closed section of Nikita Khrushchev's 1956 Report to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as "monstrous acts" and "rude violations of the basic Leninist principles of the nationality policy of the Soviet state."[28]

Central Europeans

Germans

%2C_ermordete_Deutsche.jpg)

People of German heritage had resided in Eastern Europe for years, many years before even the outbreak of World War II. In the year 1937, two years before war, the NKVD began their mass operations as part of Joseph Stalin's Great Purge. The first of these operations called for the arrests of all German citizens and former citizens. The Germans were said to be Nazi agents.[29][30]

In total, the national operation against Soviet citizens of German descent resulted in the sentencing of at least 55,005 persons, including 41,898 sentenced to death.[31]

During the war, the strategies of the Soviet Union have been criticized as racist, the extreme tactics used are theorized not only to target the Nazi forces but the German people in general. The war crimes committed such as mass rapes by Red Army soldiers are used as evidence that the Red Army viewed the German people as the enemy not the Nazi Army. Although all of this is unproven debated theory.[32]

The ethnic German minority in the USSR was considered a security risk by the Soviet government and they were deported during the war in order to prevent their possible collaboration with the Nazi invaders. In August 1941, the Soviet government ordered ethnic Germans to be deported from the European USSR. By early 1942, 1,031,300 Germans had been banished to Central Asia and Siberia. By October 1945, only 687,300 Germans remained alive in Soviet labour camps.[33]

The Soviet Union began to discuss the idea of the forced labor of Germans as war reparations, their allies did not raise any objections. By the summer of 1944, the Soviet forces had reached the Balkans that had ethnic German minorities. State Defense Committee Order 7161 of 16 December 1944 instructed to intern all able-bodied Germans of ages 17–45 (men) and 18–30 (women) residing within the territories of Romania (67,332 persons), Hungary (31,920 persons) and Yugoslavia (12,579 persons), which were under the control of the Red Army. Consequently, 111,831 (61,375 men and 50,456 women) adult ethnic Germans from Romania, Yugoslavia, and Hungary were deported for forced labor to the USSR.[34]

The Soviets classified the civilians interned into two groups; the first Group A (205,520 persons) were "mobilized internees" who were able bodied adults selected for labor; the second Group D (66,152 persons) "arrested internees" were Nazi party members, German government officials, journalists and others considered a threat by the Soviets.[35] Soviet records state that they repatriated 21,061 Polish citizens from labor camps which indicates that not all of the internees were ethnic Germans and some could have been ethnic Poles.[36]

According to J. Otto Pohl, 65,599 Germans perished in the special settlements and that an additional 176,352 unaccounted for persons "probably died in the labor army".[37] During the Stalin era, the Soviet Germans continued to be confined to the special settlements under strict supervision, in 1955 they were rehabilitated but were not allowed to return to the European USSR until 1972.

After the war, the Soviet Union deported many ethnic Germans from occupied Romania to be used as laborers.

Poles

After the Polish–Soviet War theater of the Russian Civil War, Poles were often persecuted by the Soviet Union. In 1937, NKVD Order No. 00485 enacted the beginning of the Polish repressions. The order aimed at the arrest of "absolutely all Poles" and confirmed that "the Poles should be completely destroyed". Member of the NKVD Administration for the Moscow District, A. O. Postel (Арон Осипович Постель) explained that although there was no word-for-word quote of "all Poles" in the actual Order, that was exactly how the letter was to be interpreted by the NKVD executioners. By official Soviet documentation, some 139,815 people were sentenced under the aegis of the anti-Polish operation of the NKVD, and condemned without judicial trial of any kind whatsoever, including 111,071 sentenced to death and executed in short order.[38]

The Operation was only a peak in the persecution of the Poles, which spanned more than a decade. As the Soviet statistics indicate, the number of ethnic Poles in the USSR dropped by 165,000 in that period. "It is estimated that Polish losses in the Ukrainian SSR were about 30%, while in the Belorussian SSR... the Polish minority was almost completely annihilated." Historian Michael Ellman asserts that the "national operations", particularly the "Polish operation", may constitute genocide as defined by the UN convention.[39] His opinion is shared by Simon Sebag Montefiore, who calls the Polish operation of the NKVD "a mini-genocide".[40] Polish writer and commentator, Dr Tomasz Sommer, also refers to the operation as a genocide, along with Prof. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz among others.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47]

After the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, the Soviet Union began to repress institutions of the former Polish government, although these repressions were not overtly racist the new Soviet government allowed for racial hatred. The Soviets exploited past ethnic tensions between Poles and other ethnic groups living in Poland; they incited and encouraged violence against Poles, suggesting the minorities could "rectify the wrongs they had suffered during twenty years of Polish rule".[48] Pre-war Poland was portrayed as a capitalist state based on exploitation of the working people and ethnic minorities. Soviet propaganda claimed that the unfair treatment of non-Poles by the Second Polish Republic justified its dismemberment.[49]

Hungarians

During World War II, the Soviet Union began to deport ethnic Hungarians. The first wave of deportations of Hungarian civilians was after an occupation of a Hungarian town, civilians were rounded up for "little work" regarding the removal of ruins. The largest single deportation during the first wave occurred in Budapest. Allegedly Marshal Rodion Malinovsky overestimated in his reports the number of prisoners of war taken after the Battle of Budapest, and to make the numbers some 100,000 civilians were gathered in Budapest and its neighborhood. The first wave took place mainly in north-western Hungary, on the path of the advancing Soviet Army.[50]

The second, more organized wave happened one to two months later, in January 1945, covering the whole of Hungary. According to the USSR State Defence Committee Order 7161, ethnic Germans were to be deported for forced labor from the occupied territories, including Hungary. Soviet authorities had deportation quotas for each region, and when the target was missed, it was filled up with ethnic Hungarians.[50] In addition, Hungarian prisoners of war were deported during this period.

Transcaucasians

Nakh peoples

Two ethnic groups that were specifically targeted for persecution by Stalin's Soviet Union were the Chechens and the Ingush.[51] Rather than being accused of collaboration with foreign enemies, these two ethnic groups were considered to have cultures which did not fit in with Soviet culture – such as accusing Chechens of being associated with "banditism" – and the authorities claimed that the Soviet Union had to intervene in order to "remake" and "reform" these cultures.[51] In practice this meant heavily armed punitive operations carried out against Chechen "bandits" that failed to achieve forced assimilation, culminating in an ethnic cleansing operation in 1944, which involved the arrests and deportation of over 500,000 Chechens and Ingush from the Caucasus to Central Asia and the Kazakh SSR.[52] The deportations of the Chechens and Ingush also involved the outright massacre of thousands of people, and severe conditions placed upon the deportees – they were put in unsealed train cars, with little to no food for a four-week journey during which many died from hunger and exhaustion.[53] This eviction left a permanent scar in the memory of the survivors and their descendants. 23 February is remembered as a day of tragedy by most of Ingushs and Chechens. Many in Chechnya and Ingushetia classify it as an act of genocide, as did the European Parliament in 2004.[54]

...Believes that the deportation of the entire Chechen people to Central Asia on 23 February 1944 on the orders of Stalin constitutes an act of genocide within the meaning of the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 and the Convention for the Prevention and Repression of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948.[55]

Armenians and Azerbaijanis

Ethnic tension between Armenians and Azerbaijanis can be traced back to the pre-Soviet Armenian–Azerbaijani War. The deportation of Azerbaijanis from Armenia ensued as an act of forced resettlement and ethnic cleansing throughout the 20th century.[56][57][58][59][60] As a result of Armenian-Azerbaijani interethnic conflict in the beginning of the 20th century, as well as Armenian and Azerbaijani nationalists' coordinated policy of ethnic cleansing, a substantial portion of the Armenian and Azerbaijani population was driven out from the territory of both Armenia and Azerbaijan. According to the Russian census of 1897, the town Erivan had 29,006 residents: 12,523 of them were Armenians and 12,359 were Azerbaijanis.[61] As outlined in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, Azerbaijanis (Tatars) made up 12,000 people (41%) of the 29,000 people in the city.[61][62] However, during the systematic ethnic cleansings in the Soviet era and the systematic deportation of Armenians from Persia and the Ottoman Empire during the Armenian Genocide, the capital of present-day Armenia became a largely homogenous city. According to the census of 1959, Armenians made up 96% population of the country and in 1989 more than 96,5%. Azerbaijanis then made up only 0,1% of Yerevan's population.[63] They changed Yerevan's population in favor of the Armenians by sidelining the local Muslim population.[64] As a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, not only were the Azerbaijanis of Yerevan driven away, but the Azerbaijani mosque in Yerevan was also demolished.[65][66]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Nagorno-Karabakh War broke out between the Soviet republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan. During the war, many anti-Armenian pogroms broke out. The first was the Sumgait pogrom in which citizens attacked Armenian citizens for three days.[67] Other anti-Armenian pogroms followed such as the Kirovabad pogrom, and Baku pogrom.

Southern Europeans

Greeks

The prosecution of Greeks in the USSR was gradual: at first the authorities shut down the Greek schools, cultural centres, and publishing houses. Then, the NKVD indiscriminately arrested all Greek men 16 years old or older. All Greeks who were wealthy or self-employed professionals were sought for prosecution first.[68]

Jews

After the October Revolution, Lenin and the Bolsheviks abolished the laws which regarded the Jews as an outlawed people. Whilst the Bolsheviks were opposed to all religion, Christianity as well as Judaism,[69] Stalin emerged as leader of the Soviet Union following a power struggle with Leon Trotsky after the death of Lenin. Stalin has been accused of resorting to antisemitism in some of his arguments against Trotsky, who was of Jewish heritage. Those who knew Stalin, such as Khrushchev, suggest that Stalin had long harboured negative sentiments toward Jews that had manifested themselves before the 1917 Revolution.[70]

Antisemitism in the Soviet Union commenced openly as a campaign against the "rootless cosmopolitan"[71] (a supposed euphemism for "Jew"). In his speech entitled "On Several Reasons for the Lag in Soviet Dramaturgy" at a plenary session of the board of the Soviet Writers' Union in December 1948, Alexander Fadeyev equated the cosmopolitans with the Jews. In this campaign against the "rootless cosmopolitan", many leading Jewish writers and artists were killed.[71] The Soviet press accused the Jews of "groveling before the West," helping "American imperialism," "slavish imitation of bourgeois culture" and "bourgeois aestheticism." Victimisation of Jews in the USSR at the hands of the Nazis was denied, Jewish scholars were removed from the sciences and emigration rights were denied to Jews.[72] The Stalinist antisemitic campaign ultimately culminated in the Doctors' plot in 1953. According to Patai and Patai, the Doctors' plot was "clearly aimed at the total liquidation of Jewish cultural life."[71] Communist antisemitism under Stalin shared a common characteristic with Nazi and fascist antisemitism in its belief in "Jewish world conspiracy".[73]

Immediately following the Six-Day War in 1967, the antisemic conditions started causing desire to emigrate to Israel for many Soviet Jews. On 22 February 1981, in a speech, which lasted over 5 hours, Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev denounced antisemitism in the Soviet Union.[74] While Stalin and Lenin had much of the same in various statements and speeches, this was the first time that a high-ranking Soviet official had done so in front of the entire Party.[74] Brezhnev acknowledged that antisemitism existed within the Eastern Bloc and saw that many different ethnic groups whose "requirements" were not being met.[74]

Northern and Eastern Asians

Kalmyks

The deportations of 1943, codenamed Operation Ulussy, were the deportation of most people of the Kalmyk nationality in the Soviet Union, and Russian women married to Kalmyks, except Kalmyk women married to another nationality. The Kalmyk people had been accused of collaboration with the Nazis as a whole. The decision was made in December 1943, when NKVD agents entered the homes of Kalmyks, or registered the names of those absent for deportation later, and packed them into cargo wagons and transported them to various locations in Siberia: Altai Krai, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Omsk Oblast, and Novosibirsk Oblast. Around half of (97,000–98,000) Kalmyk people deported to Siberia died before being allowed to return home in 1957.[75]

Under the Law of the Russian Federation of 26 April 1991 "On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples" repressions against Kalmyks and other peoples were qualified as an act of genocide. Article 4 of this law provided that any propaganda impeding rehabilitation of peoples is prohibited, and persons responsible for such propaganda are subject to prosecution.

Koreans

Deportation of Koreans in the Soviet Union, originally conceived in 1926, initiated in 1930, and carried through in 1937, was the first mass transfer of an entire nationality in the Soviet Union.[76] Almost the entire Soviet population of ethnic Koreans (171,781 persons) were forcefully moved from the Russian Far East to unpopulated areas of the Kazakh SSR and the Uzbek SSR in October 1937.[77] The justification for deportation resolution 1428-326cc was that it had been planned with the aim to "prevent the infiltration of Japanese spies to the Far East." However, no conclusive documents or other information on the matter have ever been found.

See also

References

- Lenin, V.I. (1914) The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, from Lenin's Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1972, Moscow, Volume 20, pp. 393–454. Available online at: http://marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/self-det/index.htm (Retrieved 30 November 2011)

- Harding, Neil (ed.) The State in Socialist Society, second edition (1984) St. Antony's College: Oxford, p. 189.

- UNPO: Chechnya: European Parliament recognizes the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944

- Naimark, Norman M. Stalin's Genocides (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 131. ISBN 0-691-14784-1

- Rosefielde, Steven (2009). Red Holocaust. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-415-77757-5.

- Davies 2006, p. 145.

- Baumeister 1999, p. 179.

- Sternberg & Sternberg 2008, p. 67.

- "The famine of 1932–33". Encyclopædia Britannica online. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33 – a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself.

- ЗАКОН УКРАЇНИ: Про Голодомор 1932–1933 років в Україні [LAW OF UKRAINE: About the Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine]. rada.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). 28 November 2006. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "International Recognition of the Holodomor". Holodomor Education. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- 'Stalinism' was a collective responsibility – Kremlin papers, The News in Brief, University of Melbourne, 19 June 1998, Vol 7 No 22

- Snyder 2010, pp. 42–46.

- Bohdan Kordan, "Making Borders Stick: Population Transfer and Resettlement in the Trans-Curzon Territories, 1944–1949" International Migration Review, Vol. 31, No. 3. (Autumn, 1997), pp. 704–720.

- Allworth, Edward (1998). The Tatars of Crimea: Return to the Homeland : Studies and Documents. Duke University Press. p. 272. ISBN 9780822319948.

- Levene, Mark (2013). Annihilation: Volume II: The European Rimlands 1939–1953. Oxford University Press. p. 333. ISBN 9780199683048.

- Naimark 2002, p. 104

- Kohl, Philip L.; Kozelsky, Mara; Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (2008). Selective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National Pasts. University of Chicago Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780226450643.

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2015). The Crimean Tatars: From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. Oxford University Press. pp. 105, 114. ISBN 9780190494704.

- Orlando Figes. A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891–1924. Penguin Books, 1998. ISBN 0-14-024364-X

- Donald Rayfield. Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him Random House, 2004. ISBN 0-375-50632-2

- Mikhail Heller & Aleksandr Nekrich. Utopia in Power: The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Present.

- R. J. Rummel (1990). Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-887-3. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Soviet order to exterminate Cossacks is unearthed Archived 2009-12-10 at the Wayback Machine University of York Communications Office, 21 January 2003

- Martin, Terry (1998). "The Origins of Soviet Ethnic Cleansing" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 70 (4): 813–861. doi:10.1086/235168. JSTOR 10.1086/235168.

- The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies Oxford University Press Inc. 2010. Retrieved 2013-05-09

- GENOCIDE IN BALTIC BY SOVIET CHARGED; Envoys of Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia Call on U.S. to Urge U.N. Investigation, The New York Times, July 28, 1950, p. 7

- Special Report to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, by Nikita Khrushchev, 1956

- Охотин Н., Рогинский А. Из истории "немецкой операции" НКВД 1937–1938 гг. // Репрессии против советских немцев. Наказанный народ. М., 1999. С. 35–75. (in Russian)

- "Foreigners in GULAG: Soviet Repressions of Foreign Citizens", by Pavel Polian (in Russian)

- English language version (shortened): P.Polian. Soviet Repression of Foreigners: The Great Terror, the GULAG, Deportations, Annali. Anno Trentasttesimo, 2001. Feltrinelli Editore Milano, 2003. – P.61-104

- Н.Охотин, А.Рогинский, Москва. Из истории "немецкой операции" НКВД 1937–1938 гг.Chapter 2

- Daniel Johnson (24 January 2002). "Red Army troops raped even Russian women as they freed them from camps". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- J. Otto Pohl-The Stalinist Penal System: A Statistical History of Soviet Repression and Terror, 1930–1953 McFarland, 1997 ISBN 0-7864-0336-5 Page 71

- Pavel Polian-Against Their Will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR Central European University Press 2003 ISBN 963-9241-68-7 P. 266 (On page 259 Polian pointed out that there are three Soviet sources each listing different figures for the total deported from the Balkans, the three figures are 112,352, 112,480 and 111,831 persons deported)

- Pavel Polian-Against Their Will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR Central European University Press 2003 ISBN 963-9241-68-7 P.249-260

- Pavel Polian-Against Their Will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR Central European University Press 2003 ISBN 963-9241-68-7 P.294(Some of the Polish citizens may have been ethnic Germans from pre-war Poland. The figures of those released do not include an additional 6,642 imprisoned Poles of the AK Home Army)

- J. Otto Pohl Ethnic cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949 Greenwood Press, 1999 ISBN 0-313-30921-3 page 54

- Robert Gellately, Ben Kiernan (2003). The specter of genocide: mass murder in historical perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 396. ISBN 0521527503.

Polish operation (page 233 –)

- Michael Ellman, Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited PDF file

- Simon Sebag Montefiore. Stalin. The Court of the Red Tsar, page 229. Vintage Books, New York 2003. Vintage ISBN 1-4000-7678-1

- Prof. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz (2011-01-15). "Nieopłakane ludobójstwo (Genocide Not Mourned)". Rzeczpospolita. Retrieved April 28, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Franciszek Tyszka. "Tomasz Sommer: Ludobójstwo Polaków z lat 1937–38 to zbrodnia większa niż Katyń (Genocide of Poles in the years 1937–38, a Crime Greater than Katyn)". Super Express. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- "Rozstrzelać Polaków. Ludobójstwo Polaków w Związku Sowieckim (To Execute the Poles. Genocide of Poles in the Soviet Union)". Historyton. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- Andrzej Macura, Polska Agencja Prasowa (2010-06-24). "Publikacja na temat eksterminacji Polaków w ZSRR w latach 30 (Publication on the Subject of Extermination of Poles in the Soviet Union during the 1930s)". Portal Wiara.pl. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- Prof. Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski (22 March 2011). "Rozkaz N.K.W.D.: No. 00485 z dnia 11-VIII-1937, a Polacy". Polish Club Online. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

See also, Tomasz Sommer: Ludobójstwo Polaków w Związku Sowieckim (Genocide of Poles in the Soviet Union), article published by The Polish Review vol. LV, No. 4, 2010.

- "Sommer, Tomasz. Book description (Opis)". Rozstrzelać Polaków. Ludobójstwo Polaków w Związku Sowieckim w latach 1937–1938. Dokumenty z Centrali (Genocide of Poles in the Soviet Union). Księgarnia Prawnicza, Lublin. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- "Konferencja "Rozstrzelać Polaków – Ludobójstwo Polaków w Związku Sowieckim" (Conference on Genocide of Poles in the Soviet Union), Warsaw". Instytut Globalizacji oraz Press Club Polska in cooperation with Memorial Society. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- Jan Tomasz Gross, Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia, Princeton University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-691-09603-1, p. 35

- Gross, op.cit., page 36

- "Forgotten Victims of World War II: Hungarian Women in Soviet Forced Labor Camps", by Ágnes Huszár Várdy, Hungarian Studies Review, (2002) vol 29, issue 1–2, pp. 77–91.

- Geyer (2009). p. 159.

- Geyer (2009). pp. 159–160.

- Geyer (2009). p. 160.

- "Chechnya: European Parliament recognises the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. February 27, 2004. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- "Texts adopted: Final edition EU-Russia relations". Brussels: European Parliament. February 26, 2004. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ""Черный сад": Глава 5. Ереван. Тайны Востока". BBC Russia. 8 July 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- dewaal 1996.

- Lowell W. Barrington (2006). After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial & Postcommunist States. USA: University of Michigan Press. pp. In late 1988, the entire Azerbaijani population (including Muslim Kurds) – some 167, 000 people – was kicked out of the Armenian SSR. In the process, dozens of people died due to isolated Armenian attacks and adverse conditions. This population transfer was partially in response to Armenians being forced out of Azerbaijan, but it was also the last phase of the gradual homogenization of the republic under Soviet rule. The population transfer was the latest, and not so "gentle, " episode of ethnic cleansing that increased Armenia's homogenization from 90 percent to 98 percent. Nationalists, in collaboration with the Armenian state authorities, were responsible for this exodus. ISBN 0-472-06898-9.

- A second reason for Armenian unity and coherence was the fact that progressively through the seventy years of Soviet power, the republic grew more Armenian in population until it became the most ethnically homogeneous republic in the USSR. On several occasions local Muslims were removed from its territory and Armenians from neighboring republics settled in Armenia. The nearly 200,000 Azerbaijanis who lived in Soviet Armenia in the early 1980s either left or were expelled from the republic in 1988–89, largely without bloodshed. The result was a mass of refugees flooding into Azerbaijan, many of them becoming the most radical opponents of Armenians in Azerbaijan.Ronald Grigor Suny (Winter 1999–2000). Provisional Stabilities: The Politics of Identities in Post-Soviet Eurasia. International Security. Vol 24, No. 3. pp. 139–178.

- Thomas Ambrosio (2001). Irredentism: ethnic conflict and international politics. USA: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 160. ISBN 0-275-97260-7. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- "Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г." Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- "Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона. "Эривань"". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- Lenore A. Grenoble (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. University of Michigan Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

- Ronald Grigor Suny (1993). Looking toward Ararat: Armenia in modern history. Indiana University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-253-20773-8.

Ronald Grigor Suny Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana State University, 1993.

- "The New Yorker, A Reporter at Large, "Roots,"". April 15, 1991.

- "Том де Ваал. Черный сад. Между миром и войной. Глава 5. Ереван. Тайны Востока". BBC News. 8 July 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- Rodina. No. 4, 1994, pp. 82–90.

- Το πογκρόμ κατά των Ελλήνων της ΕΣΣΔ, ΕΛΛΑΔΑ, 09.12.2007

- Such as:

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1958–1964)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1970s–1990)

- Ro'i, Yaacov , Jews and Jewish Life in Russia and the Soviet Union, Routledge, 1995, ISBN 0-7146-4619-9, pp. 103–6.

- Patai & Patai 1989.

- Louis Horowitz, Irving (December 3, 2007), "Cuba, Castro and Anti-Semitism" (PDF), Current Psychology, 26 (3–4): 183–190, doi:10.1007/s12144-007-9016-4, ISSN 0737-8262, OCLC 9460062

- Laqueur 2006, p. 177

- Korey, William. Brezhnev and Soviet Anti-Semitism. p. 29.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/country_profiles/4580467.stm Regions and territories: Kalmykia

- Otto Pohl, Ethnic cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, pp. 9–20; partially viewable on Google Books

- First deportation and the "Effective manager" Archived 2009-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, Novaya Gazeta, by Pavel Polyan and Nikolai Pobol