Sais, Egypt

Sais (Ancient Greek: Σάϊς, Coptic: Ⲥⲁⲓ) or Sa El Hagar (Arabic: صا الحجر) was an ancient Egyptian town in the Western Nile Delta on the Canopic branch of the Nile.[1] It was the provincial capital of Sap-Meh, the fifth nome of Lower Egypt and became the seat of power during the Twenty-fourth Dynasty of Egypt (c. 732–720 BC) and the Saite Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt (664–525 BC) during the Late Period.[2] Its Ancient Egyptian name was Zau.

Sais | |

|---|---|

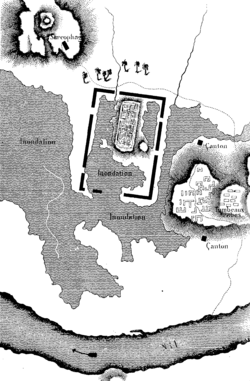

Map of Sais ruins drawn by Jean-François Champollion during his expedition in 1828 | |

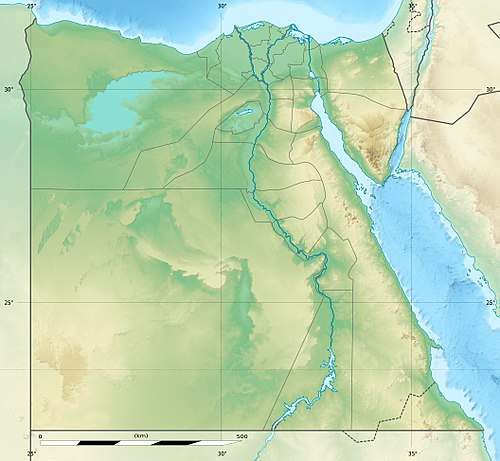

Sais Location in Egypt | |

| Coordinates: 30°57′53″N 30°46′6″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Gharbia |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EST) |

Overview

| Sais in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sau (Zau) Sȝw | ||||||

| Greek | Σάϊς (Sais) | |||||

Herodotus wrote that Sais is where the grave of Osiris was located and that the sufferings of the god were displayed as a mystery by night on an adjacent lake.[3]

The city's patron goddess was Neith, whose cult is attested as early as the First Dynasty of Egypt (c. 3100–3050 BC).[2] The Greeks, such as Herodotus, Plato, and Diodorus Siculus, identified her with Athena and hence postulated a primordial link to Athens. Diodorus recounts that Athenians built Sais before the deluge. While all Greek cities were destroyed during that cataclysm, including Athens, Sais and the others Egyptian cities survived.[4]

In Plato's Timaeus and Critias (around 395 BC, 200 years after the visit by the Greek legislator Solon), Sais is the city in which Solon receives the story of Atlantis, its military aggression against Greece and Egypt, its eventual defeat and destruction by gods-punishing catastrophe, from an Egyptian priest. Solon visited Egypt in 590 BC. Plato also notes the city as the birthplace of the pharaoh Amasis II.[5]

Plutarch said that the shrine of Athena, which he identifies with Isis, in Sais carried the inscription "I am all that hath been, and is, and shall be; and my veil no mortal has hitherto raised."[6]

Hector Berlioz' L'enfance du Christ ("The Childhood of Christ"), in part Three, has Sais as the setting for the youth of Jesus until age 10, after his parents leave their homeland to escape the Massacre of the Innocents by Herod the Great.

There are today no surviving traces of this town prior to the Late New Kingdom (c. 1100 BC) due to the extensive destruction of the city by the Sebakhin (farmers removing mud brick deposits for use as fertilizer) leaving only a few relief blocks in situ.[2]

Though the proposed Sa El Hagar site has little evidence of this city, Obelisks in Piazza della Minerva and Urbino Italy are claimed to originate from Sais.

During the Islamic conquest of Egypt, a battle was fought at Sais between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire, according to John of Nikiû. It remained a pagarchy and Christian bishopric at least through the early 700s. Medieval writers like Yaqut al-Hamawi, al-Maqrizi, and al-Qalqashandi attributed the city's foundation to one "Sā ibn Misr"; Ibn Iyas called the founder "Sā ibn Marqunus". The site was used as a stone quarry during this period. By the time of Ibn Iyas, the city had fallen almost completely into ruin.[7]

The 1885 Census of Egypt recorded Sa el-Hagar as a nahiyah under the district of Kafr az-Zayyat in Gharbia Governorate; at that time, the population of the town was 4,474 (2,250 men and 2,224 women).[8]

Medical school

The Temple of Sais had a medical school associated with it, as did many ancient Egyptian temples. The medical school at Sais had many female students and apparently women faculty as well, mainly in gynecology and obstetrics. An inscription from the period survives at Sais, and reads, "I have come from the school of medicine at Heliopolis, and have studied at the woman's school at Sais, where the divine mothers have taught me how to cure diseases".[9]

See also

References

- Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. "Saïs." Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary. 9th ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster Inc., 1985. ISBN 0-87779-508-8, ISBN 0-87779-509-6 (indexed), and ISBN 0-87779-510-X (deluxe).

- Ian Shaw & Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, 1995. p.250

- Herodotus, II, 171.

- Diodorus Siculus, Historical Library "Book V, 57".

- Plato, Timaeus.

- Plutarch, Isis and Osiris", ch. 9.

- Maspero, Jean; Wiet, Gaston (1919). Matériaux pour servir à la géographie de l'Égypte. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. p. 116.

- Egypt min. of finance, census dept (1885). Recensement général de l'Égypte. p. 279. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Silverthorne, Elizabeth and Geneva Fulgham (1997). Women Pioneers in Texas Medicine. Texas A&M University Press. pp. xvii. ISBN 978-0-89096-789-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sais, Egypt. |

| Preceded by Tanis |

Capital of Egypt 732 – 720 BC |

Succeeded by Napata/Memphis |

| Preceded by Napata/Memphis |

Capital of Egypt 664 – 525 BC |

Succeeded by Persepolis(Achaemenid Empire) |

| Preceded by Babylon(Achaemenid Empire) |

Capital of Egypt 404 – 399 BC |

Succeeded by Mendes |