Phrygian language

The Phrygian language /ˈfrɪdʒiən/ was the Indo-European language of the Phrygians, spoken in Asia Minor during Classical Antiquity (c. 8th century BC to 5th century AD).

| Phrygian | |

|---|---|

| Region | Central Asia Minor |

| Extinct | After the 5th century AD |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xpg |

xpg | |

| Glottolog | phry1239[2] |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

Phrygian is considered by some linguists to have been closely related to Greek[3][4] and/or Armenian. The similarity of some Phrygian words to Greek ones was observed by Plato in his Cratylus (410a).

Inscriptions

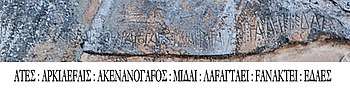

Phrygian is attested by two corpora, one dated to between about the 8th and the 4th century BC (Paleo-Phrygian), and then after a period of several centuries from between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD (Neo-Phrygian). The Paleo-Phrygian corpus is further divided (geographically) into inscriptions of Midas City (M, W), Gordion, Central (C), Bithynia (B), Pteria (P), Tyana (T), Daskyleion (Dask), Bayindir (Bay), and "various" (Dd, documents divers). The Mysian inscriptions seem to be in a separate dialect (in an alphabet with an additional letter, "Mysian s").

The last mentions of the language date to the 5th century AD, and it was likely extinct by the 7th century AD.[7]

Paleo-Phrygian used a Phoenician-derived script (its ties with Greek are debated), while Neo-Phrygian used the Greek script.

Grammar

Its structure, what can be recovered of it, was typically Indo-European, with nouns declined for case (at least four), gender (three), and number (singular and plural), while the verbs are conjugated for tense, voice, mood, person, and number. No single word is attested in all its inflectional forms.

Phrygian seems to exhibit an augment, like Greek, Indo-Iranian, and Armenian; cf. eberet, probably corresponding to Proto-Indo-European *e-bher-e-t (Greek: épʰere with loss of the final t, Sanskrit: ábharat), although comparison to examples like ios ... addaket 'who does ... to', which is not a past tense form (perhaps subjunctive), shows that -et may be from the PIE primary ending *-eti.

Phonology

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||

| Stop | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||

| Fricative | s | ||||

| Affricate | ts dz | ||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||

| Trill | r |

It has long been claimed that Phrygian exhibits a sound change of stop consonants, similar to Grimm's Law in Germanic and, more to the point, sound laws found in Proto-Armenian;[8] i.e., voicing of PIE aspirates, devoicing of PIE voiced stops and aspiration of voiceless stops. This hypothesis was rejected by Lejeune (1979) and Brixhe (1984)[9] but revived by Lubotsky (2004) and Woodhouse (2006), who argue that there is evidence of a partial shift of obstruent series; i.e., voicing of PIE aspirates (*bh > b) and devoicing of PIE voiced stops (*d > t).[10]

The affricates ts and dz developed from velars before front vowels.

Vocabulary

Phrygian is attested fragmentarily, known only from a comparatively small corpus of inscriptions. A few hundred Phrygian words are attested; however, the meaning and etymologies of many of these remain unknown.

A famous Phrygian word is bekos, meaning 'bread'. According to Herodotus (Histories 2.2) Pharaoh Psammetichus I wanted to determine the oldest nation and establish the world's original language. For this purpose, he ordered two children to be reared by a shepherd, forbidding him to let them hear a single word, and charging him to report the children's first utterance. After two years, the shepherd reported that on entering their chamber, the children came up to him, extending their hands, calling bekos. Upon enquiry, the pharaoh discovered that this was the Phrygian word for 'wheat bread', after which the Egyptians conceded that the Phrygian nation was older than theirs. The word bekos is also attested several times in Palaeo-Phrygian inscriptions on funerary stelae. It may be cognate to the English bake (PIE *bʰeh₃g-).[14] Hittite, Luwian (both also influenced Phrygian morphology), Galatian and Greek (which also exhibits a high amount of isoglosses with Phrygian) all influenced Phrygian vocabulary.[3][15]

According to Clement of Alexandria, the Phrygian word bedu (βέδυ) meaning 'water' (PIE *wed-) appeared in Orphic ritual.[16]

The Greek theonym Zeus appears in Phrygian with the stem Ti- (genitive Tios = Greek Dios, from earlier *Diwos; the nominative is unattested); perhaps with the general meaning 'god, deity'. It is possible that tiveya means 'goddess'. The shift of *d to t in Phrygian and the loss of *w before o appears to be regular. Stephanus Byzantius records that according to Demosthenes, Zeus was known as Tios in Bithynia.[17]

Another possible theonym is bago- (cf. Old Persian baga-, Proto-Slavic *bogъ "god"), attested as the accusative singular bag̣un in G-136.[18] Lejeune identified the term as *bʰagom, in the meaning 'a gift, dedication' (PIE *bʰag- 'to apportion, give a share'). But Hesychius of Alexandria mentions a Bagaios, Phrygian Zeus (Βαγαῖος Ζεὺς Φρύγιος) and interprets the name as δοτῆρ ἑάων 'giver of good things'.

See also

References

Notes

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Graeco-Phrygian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Phrygian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Brixhe, Cl. "Le Phrygien". In Fr. Bader (ed.), Langues indo-européennes, pp. 165-178, Paris: CNRS Editions.

- Brixhe, Claude (2008). "Phrygian". In Woodard, Roger D (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–80. ISBN 0-521-68496-X. "Unquestionably, however, Phrygian is most closely linked with Greek." (p. 72).

- Баюн Л. С., Орёл В. Э. Язык фригийских надписей как исторический источник. In Вестник древней истории. 1988, № 1. pp. 175-177.

- Orel, Vladimir Ė (1997). The language of Phrygians. Caravan Books. p. 14. ISBN 9780882060897.

- Swain, Simon; Adams, J. Maxwell; Janse, Mark (2002). Bilingualism in Ancient Society: Language Contact and the Written Word. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 246–266. ISBN 0-19-924506-1.

- Bonfante, G. "Phrygians and Armenians", Armenian Quarterly, 1 (1946), 82- 100 (p. 88).

- Woodard, Roger D. The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor, Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-521-68496-X, p. 74.

- Lubotsky, A. "The Phrygian Zeus and the problem of „Lautverschiebung". Historische Sprachforschung, 117. 2. (2004), 229-237.

- Woodard, Roger D. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press. p. 78. ISBN 9781139469333.

- Roller, Lynn E. (1999). In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. University of California Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780520210240.

- Corpus of Phrygian Inscriptions

- The etymology is defended in O. Panagl & B. Kowal, "Zur etymologischen Darstellung von Restsprachen", in: A. Bammesberger (ed.), Das etymologische Wörterbuch, Regensburg 1983, pp. 186–187. It is contested in Benjamin W. Fortson, Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Blackwell, 2004. ISBN 1-4051-0316-7, p. 409.

- Woodard, Roger D. The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-521-68496-X, pp. 69–81.

- Clement. Stromata, 5.8.46–47.

- On Phrygian ti- see Heubeck 1987, Lubotsky 1989a, Lubotsky 1998c, Brixhe 1997: 42ff. On the passage by Stephanus Byzantius, Haas 1966: 67, Lubotsky 1989a:85 (Δημοσθένης δ’ἐν Βιθυνιακοῖς φησι κτιστὴν τῆς πόλεως γενέσθαι Πάταρον ἑλόντα Παφλαγονίαν, καὶ ἐκ τοῦ τιμᾶν τὸν Δία Τίον προσαγορεῦσαι.) Witczak 1992-3: 265ff. assumes a Bithynian origin for the Phrygian god.

- However also read as bapun; "Un très court retour vertical prolonge le trait horizontal du Γ. S'il n'était accidentel nous aurions [...] un p assez semblable à celui de G-135." Brixhe and Lejeune 1987: 125.

Further reading

- Brixhe, Claude. "Du paléo- au néo-phrygien". In: Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 137ᵉ année, N. 2, 1993. pp. 323-344. doi:10.3406/crai.1993.15216

- Lamberterie, Charles de. "Grec, phrygien, arménien: des anciens aux modernes". In: Journal des savants, 2013, n°. 1. pp. 3-69. doi:10.3406/jds.2013.6300

- Lejeune, Michel. "Notes paléo-phrygiennes". In: Revue des Études Anciennes. Tome 71, 1969, n°3-4. pp. 287-300. doi:10.3406/rea.1969.3842

- Obrador-Cursach, Bartolomeu. "On the place of Phrygian among the Indo-European languages". In: Journal of Language Relationship (Вопросы языкового родства). 17/3 (2019). pp. 233-245.

- Orsat Ligorio & Alexander Lubotsky. “Phrygian”, in Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Vol. 3. Eds. Jared Klein, Brian Joseph, & Matthias Fritz. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2018, pp. 1816–31.

- Woodhouse, Robert. “An overview of research on Phrygian from the nineteenth century to the present day”, Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 126 (2009): 167-188. DOI 10.2478/v10148-010-0013-x.