Proposed Canadian annexation of the Turks and Caicos Islands

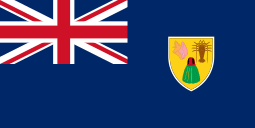

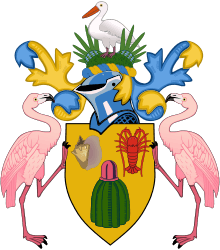

The proposed annexation of the Turks and Caicos Islands by Canada is an ongoing debate over the future political status of the island territory. The islands are currently a British Overseas Territory under the sovereignty of the United Kingdom. Thus, the Turks and Caicos and Canada are both members of the Commonwealth of Nations, and both share Queen Elizabeth II as their monarch.

The latest public opinion polling to date shows support for such a measure at 60% within the islands.[1] The Canadian government has indicated that it would be open to exploring methods of increasing economic and social ties with the Turks and Caicos, however there has been no official statement from Ottawa on the notion of transferring sovereignty over the territory from the United Kingdom.[1] At least one Canadian province has formally invited the territory into confederation.[2]

There is no consensus in either nation on how such an annexation would happen. Indeed, significant socioeconomic, diplomatic, constitutional, and political hurdles would need to be overcome to achieve incorporation of the islands.[3]

Comparison

Politics and government

Both Canada and the Turks and Caicos Islands operate under a Westminster system of government, and share Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state (in her capacity as Queen of Canada and Queen of the United Kingdom, respectively). While Canada is a sovereign, independent state that shares Elizabeth II as its monarch in free association with the other Commonwealth realms, the Turks and Caicos Islands are an internally self-governing overseas territory of the United Kingdom, in which the British monarch is represented by a resident Governor.

The foreign relations of the Turks and Caicos Islands are the responsibility of the United Kingdom, which is fulfilled through the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The FCO is headed by the Foreign Secretary, a member of the Government of the United Kingdom. Despite the United Kingdom's oversight of the territory's foreign affairs, the Turks and Caicos Islands participates in the Caribbean Community as an associate member. The Caribbean Community is an intergovernmental organization composed of 15 members and 5 associate members that promotes economic integration of the Caribbean.

Canada is a "full democracy"[4] with a tradition of liberalism[5] and strong rule of law.[6] Canada has consistently ranked very highly on the Democracy Index; in 2019, it tied for 7th in the world for strength of democracy.[4] The Turks and Caicos Islands have faced significant challenges in combating corruption[7][8][9] and has lost its right to self-government twice since achieving that status in 1976:[10] once in 1986[11] and again in 2009;[9] both times due to corruption of ministerial and public positions.

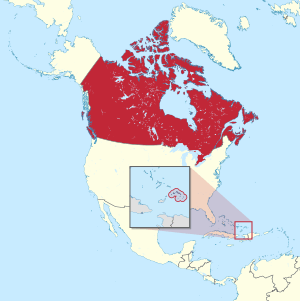

Geography

Canada has a vast and varied geography that stretches across the North American continent as the world's second biggest country by total area.[12] Canada straddles three oceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans, and only two of its provinces are landlocked, i.e. Alberta and Saskatchewan. 42 percent of the land acreage of Canada is covered by forests.[13] Much of the Canadian Arctic is covered by ice and permafrost.[14] Average winter and summer high temperatures across Canada vary from region to region. Winters can be harsh in many parts of the country.[15]

The Turks and Caicos Islands are made up of two chains of tropical islands: larger Caicos Islands and smaller Turks Islands. The territory is geographically contiguous to the Bahamas, both comprising the Lucayan Archipelago, but is politically a separate entity.[16] The country is composed of eight large islands and over twenty-two smaller islands.The climate is typical of a tropical Caribbean island state. Temperatures remain mostly consistent throughout the year: summertime temperatures rarely exceed 33 °C (91 °F) and winter nighttime temperatures rarely fall below 18 °C (64 °F).[17]

Demographics

| Arms | Province | Capital | Largest city[18] |

Entered Confederation[19] |

Population [lower-alpha 1] |

Area (km2)[21] | Official language(s)[22] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land | Water | Total | |||||||

| 14,446,515 | 917,741 | 158,654 | 1,076,395 | English[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| 8,433,301 | 1,356,128 | 185,928 | 1,542,056 | French[lower-alpha 4] | |||||

| 965,382 | 53,338 | 1,946 | 55,284 | English[lower-alpha 6] | |||||

| 772,094 | 71,450 | 1,458 | 72,908 | English, French[lower-alpha 7] | |||||

| 1,360,396 | 553,556 | 94,241 | 647,797 | English[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 8] | |||||

| 5,020,302 | 925,186 | 19,549 | 944,735 | English[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| 154,748 | 5,660 | 0 | 5,660 | English[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| 1,168,423 | 591,670 | 59,366 | 651,036 | English[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| 4,345,737 | 642,317 | 19,531 | 661,848 | English[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| 523,790 | 373,872 | 31,340 | 405,212 | English[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

| 44,598 | 1,183,085 | 163,021 | 1,346,106 | Chipewyan, Cree, English, French, Gwich'in, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey, South Slavey, Tłįchǫ[23] | |||||

| 40,369 | 474,391 | 8,052 | 482,443 | English, French[24] | |||||

| 38,787 | 1,936,113 | 157,077 | 2,093,190 | Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, English, French[25] | |||||

| Total | 37,314,442 | 9,084,507 | 900,163 | 9,984,670 | — | ||||

| Cockburn Town | Providenciales | 53,701[26] | 948[26] | 154,058[27] | 155,006 | English[26] | |||

| Total (including TCI) | 37,368,143 | 9,085,455 | 1,054,221 | 10,139,676 | — | ||||

Notes:

- As of May 10, 2016.[20]

- Ottawa, the national capital of Canada, is located in Ontario, near its border with Quebec. However, the National Capital Region straddles the border.

- De facto; French has limited constitutional status.

- Charter of the French Language; English has limited constitutional status.

- Nova Scotia dissolved cities in 1996 in favour of regional municipalities; its largest regional municipality is therefore substituted.

- Nova Scotia has very few bilingual statutes (three in English and French; one in English and Polish); some Government bodies have legislated names in both English and French.

- Section Sixteen of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

- Manitoba Act.

History

Early years

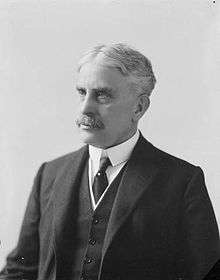

The history of the proposal extends back as far as 1917, when Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden first raised the idea of Canada taking over responsibility of the islands from the United Kingdom. The idea was raised at the Imperial Conference of that year, only to be shot down by UK Prime Minister David Lloyd George, a known supporter of strong shipping ports for his home country.[1]

Reemergence of the annexation movement (1970s)

Interest within the Turks and Caicos in joining the Canadian confederation reemerged as a serious proposal in the early 1970s.[1] Other British possessions in the Caribbean declared independence from the United Kingdom throughout the mid-20th century, including Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago in 1962, Barbados in 1966, and, importantly for the neighboring Turks and Caicos, the Bahamas in 1973.

In response to this, on 15 March 1973, the islands' territorial council prepared a petition to the Canadian government seeking a closer form of association[28] and asking Britain's permission to do so. The council sought to expand its economic integration with its large North American neighbor in the midst of a faltering domestic economy at the time.[29] An excerpt of the resolution reads:

BE IT RESOLVED AND MADE KNOWN THAT:

The State Council of the Turks and Caicos Islands desires to thank formally the Canadian People and their Government for the considerable help and advice received by these Islands from them in recent years. This State Council, recognising the urgent need for both long and short term solutions to our present constitutional, financial and economic problems, further resolves that it would welcome additional professional and technical advice from both governmental and non-governmental organisations so that we may benefit from your long and loyal membership of the British Commonwealth.

In particular, this State Council would welcome far greater official contact between our two governments and herewith cordially invite a Canadian Parliamentary Delegation to visit these Islands and advise us during these days of decision.

In 1974, a private members' bill was introduced in the federal Canadian Parliament to explore a formal association between Canada and the Turks and Caicos. The bill, entitled "An act respecting a proposed association between Canada and the Caribbean Turks and Caicos Islands",[30] did not have the support of the government at the time, not uncommon for a bill from the backbenches, and was ultimately not brought to a vote. While the bill did not proceed in Parliament, it did bring the concept of Canadian annexation back into the mainstream of Turks and Caicos Islander politics.[31]

Following the independence of its neighboring British possessions, the Turks and Caicos received their own territorial governor as well as responsible self-government. In 1976 after the first election in this new framework, the pro-independence People's Democratic Movement (PDM) won a majority of seat's in the country's House of Assembly. After election, the PDM prepared the islands for autonomy from the United Kingdom, which included a successful petition for a constitution for the islands expanding islander rights and further enhancing self-government.[32]

Height of political support (1980s)

The two predominant political parties on the islands, the pro-independence People's Democratic Movement (PDM) and the anti-independence Progressive National Party (PNP), agreed to independence by 1982. However, a territorial election in 1982 saw a return for the then governing Progressive National Party, which halted plans for independence.[7][16] The PNP, still facing sluggish economic growth and high unemployment within the islands, instead pushed for domestic reforms and closer relations with its neighbors.[1]

One of these proposals was to renew efforts to form some type of political unity with Canada. Between 1973 and 1987, members of the territory's legislature met with members of both houses of the Canadian Parliament to discuss the advantages the islands would receive by associating closely with Canada. On March 10, 1987, Liberal Senator and former Cabinet Minister Hazen Argue tabled a motion calling for both nations to explore "the desirability and advantages of the Turks and Caicos Islands becoming a part of Canada".[28] This motion referenced the ongoing talks with members of both countries' legislatures. During debate in the Canadian Senate, Argue identified advantages that the Turks and Caicos legislature saw in association with Canada:[28]

- Greater internal self-government owing to status as a territory, part of a province, or as a province in its own right;

- Utilisation of the Canadian Dollar;

- Islanders would movement and works rights as Canadian Citizens, compared to the restrictions imposed on them at the time as British Overseas citizens;

- Benefits from Canada's relationship with the United States;

- Several benefits stemming from economic integration, such as a reliable domestic tourist market;

- Domestic access to the Canadian educational system, government assistance programs, and judicial systems.

The motion also laid out concrete steps that the nations might need to take to move towards integration; the list has since been cited as the steps that both nations would need to take if the process were to be initiated in the future:

(1) adoption of a common currency;

(2) designation of Canada's Governor General as the Queen's representative for the islands (thus replacing the current Governor);

(3) a closer economic association between the two countries;

(4) any change in procedures to our mutual advantage, that would assist the entry of Canadians to the Islands, and of Islanders to Canada; and

(5) provision of efficient direct air service between the two countries.

— Hazen Argue, Senate Debates, 33rd Parliament, 2nd Session : Vol. 1

Association with Canada reached an all-time peak of support amongst islanders at this time, with around 90% of its citizens supporting it. Indeed, it seemed that having the backing of a prominent former Cabinet minister would at least propel the bill into higher media attention.[33] However, commentators generally agree that the publicity of another prominent foreign affairs discussion, the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement (which would later become the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)), distracted both politicians in Ottawa as well as Canadian media from focusing on seriously considering annexing the islands.[1] After its introduction in the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Senate, Argue's bill did not proceed to the floor.[1]

1990s to present

The combination of NAFTA's domination in Canadian politics throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, as well as growing rights for Turks and Caicos Islanders as a dependency of the United Kingdom, are seen as leading to a decline in interest in Canada's association with the islands.[1][33] In 2002, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the British Overseas Territories Act 2002 which granted full British citizenship to citizens of British Overseas Territories (such as the Turks and Caicos Islands), on par with their counterparts in the United Kingdom.[34] The act directly addressed a number of concerns of the islander government in their discussions with the Canadian government asking for closer association. The act removed barriers for islanders to immigrate and work in the UK, and only served to further lower discussion in mainstream politics of unification with Canada.

However, the suspension of the island's self-government between 2009 and 2012 over ministerial corruption[16] has re-energized the debate over the islands' future as a British Overseas Territory. In particular, dissatisfaction with losing home rule by Britain has led some to favor independence or a change in sovereign patronage vis-a-vis Canada.[35]

Opinions

Opposition

Opposition to annexation exist on in both Canada and the Turks and Caicos alike. Opponents of annexation cite issues ranging from cultural differences, political concerns over corruption, and foreign policy implications for Canada.

Following a 2009 report from a UK commission of inquiry, the British government suspended self-government for the islands over findings of significant corruption in the Turks and Caicos' government. The Premier of the islands, Michael Misick, resigned in the wake of the suspension and was viewed as a central component to dispensing political favors to other connected elites. Critics contend that issues such as these with self-government, the second time it has occurred in the history of the territory, would make the Turks and Caicos an unsuitable candidate for inclusion in Canada's strong democratic values.[1][8]

Traditionally, Canada has traditionally maintained a foreign policy as a peacekeeping middle power,[31] and its commitment to multiculturalism and multilateralism[36] has led some to decry expansionist policies as inconsistent with these values. Supporters counter that annexation would not occur without the consent of the islands' population, and thus would be in furtherance of, rather than a detriment to, Canada's values of multiculturalism.[7]

Proposed methods of union

There are multiple proposals for political union, all with certain supporters and detractors, and many variations within each.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Canada |

| Government (structure) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related topics

|

|

|

In every method, the consent of at least the federal Canadian Parliament and the governing authorities of the Turks and Caicos would be necessary for annexation.[37] Thus, overwhelming public support in both countries would have to support annexation for it to occur. The United Kingdom would be involved in these negotiations; however, the official position of the UK Government has been to support the self-determination of its overseas territories,[38] and thus would not prevent the Turks and Caicos from becoming a part of Canada if the citizens of the islands supported that move.[3] This position was reaffirmed by the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office with respect to the Turks and Caicos in 1987.[39]

All methods of annexation would require an amendment to the Canadian Constitution.[40]

Establishment as a new province

The establishment of the islands as a new province in their own right would provide the maximum level of autonomy for the Turks and Caicos under all proposed methods of annexation by putting it legally on a par with the existing 10 provinces. The Premier of the Turks and Caicos Islands has said this method would be the most desirable form of annexation for the islanders.[41]

However, becoming a province would also be the most politically challenging method, as it would require amending under the general procedure of the Constitution Act of 1982, requiring the support of the federal parliament and two-thirds of provincial legislatures that represent more than 50% of the Canadian population. It is improbable that this number could be achieved, as the addition of a new province has the potential to divide federal payments to existing provinces.[1] It is likely that incorporation of the less affluent Turks and Caicos would result in the islands siphoning funds from equalization payments from other less wealthy provinces, reducing their chances of supporting this method.[42]

Establishment as a territory

The incorporation of the Turks and Caicos Islands as a territory of Canada would be the simplest method of annexation from a legal and constitutional standpoint. The establishment of territories requires a simple act of the federal parliament, and does not require any action on the part of the provinces. A similar procedure was used in 1993 to establish Nunavut.[43]

Incorporation into an existing province

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Turks and Caicos Islands |

Some proponents of annexation have suggested that incorporation into an existing province would be the most feasible method of annexation. This method would skirt the normal process for amending the Canadian Constitution by taking advantage of the less rigorous formula under Section 43 of the Constitution Act, 1982. This prescribes that portions of the constitution affecting only one province can be amended with the consent of the federal Parliament and the legislature of that province. Thus, it is probable that annexation could be achieved using this method with general public support throughout Canada in addition to support from one willing province, as well as public support in the Turks and Caicos.

This proposal has already been officially supported by one province, Nova Scotia, in April 2004 when its legislature adopted a resolution explicitly inviting the government of the Turks and Caicos to explore joining Canada as a part of that province. The full text of the resolution reads:[2]

Whereas the Turks and Caicos is a Caribbean treasure consisting of 40 islands and a population of almost 19,000 people that is currently governed as a British territory; and

Whereas the Government of Turks and Caicos has expressed an interest in joining Canada; and

Whereas the Province of Nova Scotia has a long and proud history of conducting trade with the Caribbean;

Therefore be it resolved that the Government of Nova Scotia initiate discussions with the Turks and Caicos to become part of the Province of Nova Scotia and encourage the Government of Canada to welcome the Turks and Caicos as part of our country.

References

- "The 11th province?". Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- david (2010-04-12). "59_1_house_04apr21.htm". Nova Scotia Legislature. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- GESSELL, PAUL. "Canada's fantasy islands | Maclean's | MARCH 30, 1987". Maclean's | The Complete Archive. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- "EIU Democracy Index 2019 - World Democracy Report". www.eiu.com. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- Westhues, Anne; Wharf, Brian (25 May 2012). Canadian social policy : issues and perspectives (Fifth ed.). Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. ISBN 978-1-55458-409-3. OCLC 759030019.

- Taub, Amanda (2017-06-27). "Canada's Secret to Resisting the West's Populist Wave". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "About the Turks and Caicos Government". Visit Turks and Caicos Islands. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- Auld, Robert (7 October 2008). "Turks and Caicos Islands Commission of Inquiry 2008-2009" (PDF). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk.

- Jones, Sam (2009-08-14). "UK seizes control of Turks and Caicos over sleaze allegations". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "The Turks and Caicos Islands (Constitution) Order 1976". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "Turks and Caicos Islands (Hansard, 25 July 1986)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "The World Factbook", Wikipedia, 2020-01-30, retrieved 2020-04-04

- Luckert, Martin K. (2011). Policies for sustainably managing Canada's forests : tenure, stumpage fees, and forest practices. Haley, David., Hoberg, George. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2066-0. OCLC 903693569.

- Seufert, W.; Jentsch, S. (August 1992). "In vivo function of the proteasome in the ubiquitin pathway". The EMBO Journal. 11 (8): 3077–3080. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05379.x. ISSN 0261-4189.

- "Statistics: Regina, SK, Canada - The Weather Network". 2009-01-05. Archived from the original on 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "Turks and Caicos Islands | Location, People, & History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "Weather Today". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- Place name (2013). "Census Profile". Statistic Canada. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- Reader's Digest Association (Canada); Canadian Geographic Enterprises (2004). The Canadian Atlas: Our Nation, Environment and People. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-55365-082-9.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data". Statistics Canada. February 6, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- "Land and freshwater area, by province and territory". Statistics Canada. 2005. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- Coche, Olivier; Vaillancourt, François; Cadieux, Marc-Antoine; Ronson, Jamie Lee (2012). "Official Language Policies of the Canadian Provinces" (PDF). Fraser Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- Northwest Territories Official Languages Act, 1988 (as amended 1988, 1991–1992, 2003)

- "OCOL – Statistics on Official Languages in Yukon". Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages. 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- "Nunavut's Official Languages". Language Commissioner of Nunavut. 2009. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- "World Factbook - Turks and Caicos Islands".

- "Turks and Caicos Islands". UK Overseas Territories Conservation Forum. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- "Senate Debates, 33rd Parliament, 2nd Session : ... - Canadian Parliamentary Historical Resources". parl.canadiana.ca. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- "The Montreal Gazette - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- Canada. Parliament. House of Commons (1974). Journals of the House of Commons of Canada - Second session of the twenty-ninth Parliament of Canada, 1974. Robarts - University of Toronto. Ottawa : Queen's Printer.

- Denton, Herbert H. (1987-05-29). "CANADA HEARS SIREN CALL OF ISLANDS IN THE SUN". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- "The Turks and Caicos Islands (Constitution) Order 1976". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- "Could the Turks and Caicos Islands join Canada to become the 11th province? | News". dailyhive.com. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- "British Overseas Territories Act 2002". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "Clinging to Comforts of Colonialism in Turks and Caicos : Islanders, Uneasy at Notion of Full Independence, Weigh Canadian Ties". Los Angeles Times. 1987-10-04. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- =Banerjee, Ajit M.; Sharma, Murari R. (2007). Reinventing the United Nations. New Delhi: Prentice-Hall of India. ISBN 978-81-203-3282-9. OCLC 294882382.

- CONTI, ERIKA (2008-09-01). "The Referendum for Self-Determination: Is It Still a Solution? The Never Ending Dispute over Western Sahara". African Journal of International and Comparative Law. 16 (2): 178–196. doi:10.3366/E0954889008000169. ISSN 0954-8890.

- "British Overseas Territories: Self-determination of States:Written question - 33851". UK Parliament. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Denton, Herbert (1987). "CANADA HEARS SIREN CALL OF ISLANDS IN THE SUN". The Washington Post.

- Branch, Legislative Services (2015-07-30). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Access to Information Act". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- News; Canada (2013-07-01). "Turks and Caicos could be like a tiny Nunavut or Canada's 11th province | National Post". Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- "Does Turks and Caicos even want to join Canada? We sent a reporter to find out". Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Branch, Legislative Services (2019-07-15). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Nunavut Act". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

_(cropped).jpg)