Polk County, Tennessee

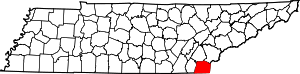

Polk County is a county located in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2018 census estimate, the population was 16,898.[2] Its county seat is Benton.[3] The county was created on November 28, 1839, from parts of Bradley and McMinn counties. The county was named after then-governor (and future president) James K. Polk.

Polk County | |

|---|---|

Polk County Courthouse in Benton | |

Location within the U.S. state of Tennessee | |

Tennessee's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 35°08′N 84°31′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | November 28, 1839 |

| Named for | James K. Polk[1] |

| Seat | Benton |

| Largest town | Benton |

| Area | |

| • Total | 442 sq mi (1,140 km2) |

| • Land | 435 sq mi (1,130 km2) |

| • Water | 7.7 sq mi (20 km2) 1.7%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018) | 16,898 |

| • Density | 39/sq mi (15/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 3rd |

| Website | www |

Polk County is included in the Cleveland, Tennessee, metropolitan statistical area, which is also included in the Chattanooga-Cleveland-Dalton, TN-GA-AL Combined Statistical Area.

History

Prior to the settlement of the Europeans, Polk County was inhabited by the Cherokee. The portion of Polk County north of the Hiwassee River was ceded from the Cherokee Nation to the US in the Calhoun Treaty of 1819. The rest of the county was part of the Ocoee District, of which the Cherokee were forcibly removed from in 1838 in an event that became known as the Trail of Tears.[1]

Polk County was created by an act of the Tennessee General Assembly on November 23, 1839. The location for the county seat of Benton was chosen on an election held on February 4, 1840.[1]

Copper was discovered in Ducktown in 1843, and by the 1850s a large mining operation was taking place in a region in southeastern Polk County that came to be known as the Copper Basin. This operation continued until 1987, when the last mine closed.

During the Civil War, Polk County was one of only six counties in East Tennessee to support the Confederacy, voting in favor of Tennessee's ordinance of secession in June 1861. During the war, the copper mines supplied about 90% of the Confederacy's copper; their capture after the Confederate defeat at the Battles for Chattanooga in November 1863 proved a major blow to the Confederacy. On November 29, 1864, a series of raids by Confederate bushwhacker John P. Gatewood in Polk County resulted in at least 16 deaths.[1]

The East Tennessee Power Company, later the Tennessee Electric Power Company (TEPCO), constructed two hydroelectric dams on the Ocoee River, Ocoee Dams 1 and 2, which were completed in 1911 and 1913, respectively.[4] TEPCO was later purchased by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which constructed an additional dam, Ocoee Dam No. 3, completed in 1943, on the Ocoee, as well as the powerhouse for Apalachia Dam on the Hiwassee River in northern Polk County, which was also completed in 1943.[5]

In 1973, a large music festival known as the "Midwest Monster Peace Jubilee and Music Festival", commonly known as the "Monster Peace Jubilee", was planned by Indiana-based promoter C.F. Manifest Inc. to take place on a 1,300 acre farm north of Benton on Labor Day of that year owned by the then county executive, now the site of the Chilhowee Gliderport. Nicknamed "Polkstock" due to its resemblance to 1969's Woodstock in Bethel, New York, the event was expected to attract approximately 500,000 and was strongly opposed by locals, especially the religious community, who believed the festival would bring much of the perceived rock music culture. The festival was eventually shut down by the state circuit court, on the request of the district attorney, that the festival would constitute a public nuisance, due to drug, health, and traffic problems.[6]

On May 27, 1983, a massive explosion at a secret illegal fireworks factory killed eleven workers. The operation, located on a bait farm a few miles south of Benton, was unlicensed, and produced M-80 and M-100 fireworks, both illegal in Tennessee, and was the largest illegal fireworks operation in the United States to date.[7]

The Ocoee Whitewater Center was the site of the canoe slalom events for the 1996 Summer Olympics.

In April 2019, Polk County was the first county in Tennessee to become a Second Amendment sanctuary.[8]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 442 square miles (1,140 km2), of which 435 square miles (1,130 km2) is land and 7.7 square miles (20 km2) (1.7%) is water.[9] The total area is 1.65% water. Located in the extreme southeastern corner of Tennessee, it is the state's only county to share borders with both Georgia and North Carolina.

Much of the terrain of eastern Polk County is mountainous, including Big Frog Mountain, constituting part of the southern Appalachian Mountains. Large tracts of Polk County are part of the Cherokee National Forest. The Ocoee River, site of whitewater slalom events in the Atlanta 1996 Summer Olympic Games, runs through Polk County and is vital to one of the county's major industries, whitewater rafting. The calmer Hiwassee River, a tributary of the Tennessee River which flows through northern Polk County, is also used for rafting and tubing. The Copper Basin is located in the extreme southeastern part of Polk County.

Adjacent counties

- Monroe County (northeast)

- Cherokee County, North Carolina (east)

- Fannin County, Georgia (southeast)

- Murray County, Georgia (southwest)

- Bradley County (west)

- McMinn County (northwest)

National protected areas

- Big Frog Wilderness (part)

- Cherokee National Forest (part)

State protected areas

- William L. Davenport Refuge

- Ducktown Basin Museum and Burra Burra Mine (state historic site)

- Fourth Fractional Township Wildlife Management Area

- Hiwassee/Ocoee Scenic River State Park

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 3,570 | — | |

| 1850 | 6,338 | 77.5% | |

| 1860 | 8,726 | 37.7% | |

| 1870 | 7,369 | −15.6% | |

| 1880 | 7,269 | −1.4% | |

| 1890 | 8,361 | 15.0% | |

| 1900 | 11,357 | 35.8% | |

| 1910 | 14,116 | 24.3% | |

| 1920 | 14,243 | 0.9% | |

| 1930 | 15,686 | 10.1% | |

| 1940 | 15,473 | −1.4% | |

| 1950 | 14,074 | −9.0% | |

| 1960 | 12,160 | −13.6% | |

| 1970 | 11,669 | −4.0% | |

| 1980 | 13,602 | 16.6% | |

| 1990 | 13,643 | 0.3% | |

| 2000 | 16,050 | 17.6% | |

| 2010 | 16,825 | 4.8% | |

| Est. 2018 | 16,898 | [10] | 0.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[11] 1790-1960[12] 1900-1990[13] 1990-2000[14] 2010-2014[2] | |||

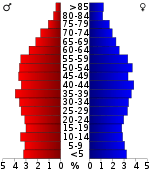

As of the census[16] of 2010, there were 16,825 people, 6,653 households, and 4,755 families residing in the county. The population density was 38.7 people per square mile. There were 7,991 housing units at an average density of 18.4 per square mile. The racial makeup of the county was 97.53% White, 0.38% Native American, 0.30% African American, 0.14% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, and 1.21% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origins, regardless of race, constituted 1.38% of the population.

There were 6,653 households out of which 26.10% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.60% were married couples living together, 9.00% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.30% were non-families. 25.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 2.96.

In the county, the population was spread out with 22.14% under the age of 18, 5.0% from 20 to 24, 10.20% from 25 to 34, 21.60% from 35 to 49, 21.70% from 50-64, and 17.10% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.5 years.

In 2000, the median income for a household in the county was $29,643, and the median income for a family was $36,370. Males had a median income of $27,703 versus $21,010 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,025. About 9.70% of families and 13.00% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.80% of those under age 18 and 18.40% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Public schools in Polk County are operated by the Polk County Schools district. High Schools include Copper Basin High School and Polk County High School. The district has one middle schools, Chilhowee Middle. The district also has three elementary schools, Benton Elementary, South Polk Elementary and Copper Basin Elementary.[17]

Communities

Cities

Town

- Benton (county seat)

Unincorporated Communities

- Cherokee Hills

- Coalhill

- Conasauga

- Delano

- Dogtown

- Farner

- Harbuck

- Isabella

- Ocoee

- Oldfort

- Parksville

- Postelle

- Reliance

- Turtletown

Ghost Towns[18]

- Probst

- Bonnie

- McFarland

- Sylco

- Hidgon's Store

- Alaculsy

- Old Dutch Settlement

- Broad Shoals

- Smith Creek Village

- Apalachia

- Apalachia Station

- Caney Creek

- McHarge

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 78.2% 5,097 | 19.2% 1,252 | 2.6% 171 |

| 2012 | 67.8% 4,108 | 30.6% 1,856 | 1.6% 95 |

| 2008 | 65.6% 4,267 | 32.7% 2,124 | 1.7% 110 |

| 2004 | 58.6% 3,924 | 40.7% 2,724 | 0.8% 52 |

| 2000 | 52.0% 2,907 | 46.0% 2,574 | 2.0% 113 |

| 1996 | 40.0% 1,910 | 51.4% 2,450 | 8.6% 410 |

| 1992 | 34.4% 1,584 | 56.0% 2,583 | 9.6% 443 |

| 1988 | 52.3% 2,297 | 47.2% 2,073 | 0.5% 21 |

| 1984 | 56.2% 2,785 | 42.6% 2,112 | 1.3% 63 |

| 1980 | 48.7% 2,414 | 49.8% 2,470 | 1.5% 76 |

| 1976 | 35.6% 1,835 | 63.7% 3,284 | 0.7% 36 |

| 1972 | 60.6% 2,285 | 37.9% 1,431 | 1.5% 56 |

| 1968 | 45.0% 1,808 | 36.2% 1,454 | 18.8% 754 |

| 1964 | 44.4% 1,685 | 55.6% 2,113 | |

| 1960 | 58.3% 2,187 | 40.8% 1,532 | 0.9% 32 |

| 1956 | 58.2% 2,136 | 41.8% 1,533 | |

| 1952 | 55.6% 2,283 | 44.4% 1,821 | |

| 1948 | 51.1% 1,529 | 47.2% 1,412 | 1.6% 49 |

| 1944 | 7.2% 378 | 92.7% 4,842 | 0.1% 6 |

| 1940 | 13.5% 562 | 86.5% 3,611 | |

| 1936 | 43.2% 1,755 | 56.2% 2,283 | 0.6% 24 |

| 1932 | 39.3% 1,642 | 60.7% 2,540 | |

| 1928 | 63.2% 1,760 | 36.4% 1,012 | 0.4% 12 |

| 1924 | 51.3% 1,247 | 47.3% 1,150 | 1.4% 34 |

| 1920 | 56.2% 1,018 | 42.8% 775 | 1.0% 18 |

| 1916 | 53.1% 887 | 45.9% 767 | 1.0% 17 |

| 1912 | 26.2% 533 | 42.7% 867 | 31.1% 631 |

Transportation

Air

Polk County is served by Martin Campbell Field, a general aviation airport.[20] The Chilhowee Gliderport is an FAA-licensed gliderport located near Benton.[21]

Notable people

- Stan Beaver, musician.

- Landrum Bolling, journalist.

- Randy Buehler, game developer.

- Joel Eaves, basketball coach.

- G. Earl Guinn, university president.

- Elizabeth Hamer Kegan, librarian.

- John E. Hutton, U.S. representative.

- Rick Tyler, white supremacist.

References

- Marian Bailey Presswood, "Polk County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: March 19, 2013.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- James B. Jones, Jr. Towards an Understanding of the History and Material Culture of Pre-TVA Hydroelectric Development in Tennessee, 1900-1933. Retrieved: 22 January 2009. PDF.

- Tennessee Valley Authority, The Hiwassee Valley Projects Volume 2: The Apalachia, Ocoee No. 3, Nottely, and Chatuge Projects, Technical Report No. 5 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1948), pp. 1-13, 40, 47, 63, 295, 494.

- "Judge Orders Festival Halted". Kingsport Times-News. Kingsport, Tennessee. August 24, 1973. Retrieved February 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jefferson, Jon; Bass, William (September 4, 2007). Beyond The Body Farm: A Legendary Bone Detective Explores Murders, Mysteries, and the Revolution in Forensic Science. Harper Collins. pp. 67–86. ISBN 0060875283 – via Google Books.

- Bowers, Larry C. (April 21, 2019). "Polk is first county in state to be 'gun sanctuary'". Cleveland Daily Banner. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Based on 2010 census data

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- "POLK CO SCHOOLS". polk-schools.businesscatalyst.com. Polk County Board of Education. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- "hiwassee river forum - Anyone know what this is?". hiwassee.net. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- "MARTIN CAMPBELL FIELD - 1A3". tdot.state.tn.us. Tennessee Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- FAA Airport Master Record for 92A (Form 5010 PDF)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polk County, Tennessee. |

- Official site

- Polk County/Copper Basin Chamber of Commerce

- Polk County, TNGenWeb - free genealogy resources for the county

- Polk County at Curlie