1996 Summer Olympics

The 1996 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XXVI Olympiad, commonly known as Atlanta 1996, and also referred to as the Centennial Olympic Games,[2][3][4] were an international multi-sport event that was held from July 19 to August 4, 1996, in Atlanta, Georgia. These Games, which were the fourth Summer Olympics to be hosted by the United States, marked the centennial of the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens—the inaugural edition of the modern Olympic Games. They were also the first since 1924 to be held in a different year from a Winter Olympics, under a new IOC practice implemented in 1994 to hold the Summer and Winter Games in alternating, even-numbered years.

| |||

| Host city | Atlanta, Georgia, United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motto | The Celebration of the Century | ||

| Nations | 197 | ||

| Athletes | 10,320 (6,797 men, 3,523 women) | ||

| Events | 271 in 26 sports (37 disciplines) | ||

| Opening | July 19 | ||

| Closing | August 4 | ||

| Opened by | |||

| Cauldron | |||

| Stadium | Centennial Olympic Stadium | ||

| Summer | |||

| |||

| Winter | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

|

More than 10,000 athletes from 197 National Olympic Committees competed in 26 sports, including the Olympic debuts of beach volleyball, mountain biking, and softball, as well as the new disciplines of lightweight rowing and women's football (soccer). 24 countries made their Summer Olympic debut in Atlanta, including eleven former Soviet republics participating for the first time as independent nations. The hosting United States led the medal count with a total of 101 medals, and the most gold (44) and silver (32) medals out of all countries. The U.S. topped the medal count for the first time since 1984, and for the first time since 1968 in a non-boycotted Summer Olympics. Notable performances during competition included those of Andre Agassi—who became the first men's singles tennis player to combine a career Grand Slam with an Olympic gold medal, Donovan Bailey—who set a new world record of 9.84 for the men's 100 meters, and Lilia Podkopayeva—who became the second gymnast to win an individual event gold after winning the all-round title in the same Olympics.

The festivities were marred by violence on July 27, when Eric Rudolph detonated pipe bombs at Centennial Olympic Park—a downtown park that was built to serve as a public focal point for the Games' festivities, killing 1 and injuring 111. In 2003, Rudolph confessed to the bombing and a series of related attacks on abortion centers and a gay bar, and was sentenced to life in prison. He claimed that the bombing was meant to protest the U.S. government's sanctioning of "abortion on demand".

The Games turned a profit, helped by record revenue from sponsorship deals and broadcast rights, and reliance on private funding (as opposed to the extensive public funding used on later Olympics), among other factors. The Games faced criticism for being overly commercialized, as well as other issues noted by European officials, such as the availability of food and transport. The event had a lasting impact on the city; Centennial Olympic Park led a revitalization of Atlanta's downtown area and has served as a symbol of the Games' legacy, the Olympic Village buildings have since been used as residence housing for area universities, and the Centennial Olympic Stadium has been re-developed twice since the Games—first as the baseball park Turner Field, and then as the college football venue Georgia State Stadium.

The Games were succeeded by the 1996 Summer Paralympics.

Bidding process

Atlanta was selected on September 18, 1990, in Tokyo, Japan, over Athens, Belgrade, Manchester, Melbourne, and Toronto at the 96th IOC Session. The city entered the competition as a dark horse, being up against stiff competition.[5] The US media also criticized it as a second-tier city and complained of Georgia's Confederate history. However, the IOC Evaluation Commission ranked Atlanta's infrastructure and facilities the highest, while IOC members said that it could guarantee large television revenues similar to the success of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.[6] Additionally, former US ambassador to the UN and Atlanta mayor Andrew Jackson Young touted Atlanta's civil rights history and reputation for racial harmony. Young also wanted to showcase a reformed American South. The strong economy of Atlanta and improved race relations in the South helped to impress the IOC officials.[7] The Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) also proposed a substantial revenue-sharing with the IOC, USOC, and other NOCs.[7] Atlanta's main rivals were Toronto, whose front-running bid that began in 1986 had chances to succeed after Canada had held a successful 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, and Melbourne, Australia, who hosted the 1956 Summer Olympics and after Brisbane, Australia's failed bid for the 1992 games (which were awarded to Barcelona) and prior to Sydney, Australia's successful 2000 Summer Olympics bid. This would be Toronto's fourth failed attempt since 1960 (tried in 1960, 1964, and 1976, but defeated by Rome, Tokyo and Montreal).[8]

Greece, the home of the ancient and first modern Olympics, was considered by many observers the "natural choice" for the Centennial Games.[6][7] However, Athens bid chairman Spyros Metaxa demanded that it be named as the site of the Olympics because of its "historical right due to its history", which may have caused resentment among delegates. Furthermore, the Athens bid was described as "arrogant and poorly prepared", being regarded as "not being up to the task of coping with the modern and risk-prone extravaganza" of the current Games. Athens faced numerous obstacles, including "political instability, potential security problems, air pollution, traffic congestion and the fact that it would have to spend about $3 billion to improve its infrastructure of airports, roads, rail lines and other amenities".[6][9][10] Athens lost its bid to host the games to Atlanta in 1990, but was later chosen to host the 2004 Summer Olympics in September 1997 after Atlanta hosted the previous year.

| 1996 Summer Olympics bidding results[11] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | NOC Name | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Round 4 | Round 5 |

| Atlanta | 19 | 20 | 26 | 34 | 51 | |

| Athens | 23 | 23 | 26 | 30 | 35 | |

| Toronto | 14 | 17 | 18 | 22 | — | |

| Melbourne | 12 | 21 | 16 | — | — | |

| Manchester | 11 | 5 | — | — | — | |

| Belgrade | 7 | — | — | — | — | |

Development and preparation

Budget

The total cost of the 1996 Summer Olympics was estimated to be around $1.7 billion.[13] The venues and the Games themselves were funded entirely via private investment,[14] and the only public funding came from the U.S. government for security, and around $500 million of public money used on physical public infrastructure including streetscaping, road improvements, Centennial Olympic Park (alongside $75 million in private funding), expansion of the airport, improvements in public transportation, and redevelopment of public housing projects.[15] $420 million worth of tickets were sold, sale of sponsorship rights accounted for $540 million, and sale of the domestic broadcast rights to NBC accounted for $456 million. In total, the Games turned a profit of $10 million.[16][13]

Venues and infrastructure

Events of the 1996 Games were held in a variety of areas. A number were held within the Olympic Ring, a 3 mi (4.8 km) circle from the center of Atlanta. Others were held at Stone Mountain, about 20 miles (32 km) outside of the city. To broaden ticket sales, other events, such as Association football (soccer), were staged in various cities in the Southeast.[17][18]

- Alexander Memorial Coliseum – Boxing

- Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium – Baseball

- Centennial Olympic Stadium – Opening/Closing Ceremonies, Athletics

- Clayton County International Park (Jonesboro, Georgia) – Beach Volleyball

- Forbes Arena – Basketball

- Georgia Dome – Basketball (final), Gymnastics (artistic), Handball (men's final)

- Georgia International Horse Park (Conyers, Georgia) – Cycling (mountain), Equestrian, Modern pentathlon (riding, running)

- Georgia State University Sports Arena – Badminton

- Georgia Tech Aquatic Center – Diving, Modern pentathlon (swimming), Swimming, Synchronized Swimming, Water Polo

- Georgia World Congress Center – Fencing, Handball, Judo, Modern pentathlon (fencing, shooting), Table Tennis, Weightlifting, Wrestling

- Golden Park (Columbus, Georgia) – Softball

- Herndon Stadium – Field hockey (final)

- Lake Lanier (Gainesville, Georgia) – Canoeing (sprint), Rowing

- Legion Field (Birmingham, Alabama) – Football

- Miami Orange Bowl (Miami, Florida) – Football

- Omni Coliseum – Volleyball (indoor final)

- Ocoee Whitewater Center (Polk County, Tennessee) – Canoeing (slalom)

- Panther Stadium – Field hockey

- RFK Stadium (Washington, D.C.) – Football

- Stone Mountain Tennis Center (Stone Mountain, Georgia) – Tennis

- Stone Mountain Park Archery Center (Stone Mountain, Georgia) – Archery

- Stone Mountain Park Velodrome (Stone Mountain, Georgia) – Cycling (track)

- Sanford Stadium (Athens, Georgia) at the University of Georgia – Football (final)

- Stegeman Coliseum (Athens, Georgia) at the University of Georgia – Gymnastics (rhythmic), Volleyball (indoor)

- Wassaw Sound (Savannah, Georgia) – Sailing

- Wolf Creek Shooting Complex – Shooting

Marketing

The Olympiad's official theme, "Summon the Heroes", was written by John Williams, making it the third Olympiad at that point for which he had composed (official composer 1984; NBC's coverage composer 1988). The opening ceremony featured Céline Dion singing "The Power of the Dream", the official theme song of the 1996 Olympics. The mascot for the Olympiad was an abstract, animated character named Izzy. In contrast to the standing tradition of mascots of national or regional significance in the city hosting the Olympiad, Izzy was an amorphous, fantasy figure. Atlanta's Olympic slogan "Come Celebrate Our Dream" was written by Jack Arogeti, a Managing Director at McCann-Erickson in Atlanta at the time. The slogan was selected from more than 5,000[19] submitted by the public to the Atlanta Convention and Visitors Bureau. Billy Payne noted that Jack "captured the spirit and our true motivation for the Olympic games."[20]

The 1996 Olympics were the first to have two separate opening ceremony events. The city of Savannah, Georgia (host of the yachting events) held its own local festivities, including a local cauldron lighting event on the first day of the Games (headlined by a performance by country musician Trisha Yearwood).[21]

The syndicated game show Wheel of Fortune taped three weeks of Olympics-themed episodes from the Fox Theater in Atlanta for broadcast in April and July 1996, which included prizes from the Games' official sponsors.[22][23] A video game featuring the Games' mascot, Izzy's Quest for the Olympic Rings, was also released.[24]

Calendar

- All times are in Eastern Daylight Time (UTC-4); the other, Birmingham, Alabama uses Central Daylight Time (UTC-5)

| ● | Opening ceremony | Event competitions | ● | Event finals | ● | Closing ceremony |

| Date | July | August | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19th Fri | 20th Sat | 21st Sun | 22nd Mon | 23rd Tue | 24th Wed | 25th Thu | 26th Fri | 27th Sat | 28th Sun | 29th Mon | 30th Tue | 31st Wed | 1st Thu | 2nd Fri | 3rd Sat | 4th Sun | |

| Archery | ● | ● | ● ● | ||||||||||||||

| Athletics | ● ● | ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● | ||||||||

| Badminton | ● ● | ● ● ● |

|||||||||||||||

| Baseball | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Basketball | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Boxing | ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Canoeing | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● | |||||||||||||

| Cycling | ● | ● | ● | ● ● | ● ● ● ● |

● ● | ● | ● ● | |||||||||

| Diving | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Equestrian | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||

| Fencing | ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● | ● ● | ● ● | |||||||||||

| Field hockey | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Football | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Gymnastics | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● | ● | |||||||||

| Handball | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Judo | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ||||||||||

| Modern pentathlon | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Rowing | ● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||||||

| Sailing | ● | ● ● ● |

● | ● ● | ● ● | ● | |||||||||||

| Shooting | ● ● | ● ● | ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | ● ● | |||||||||

| Softball | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Swimming | ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

||||||||||

| Synchronized swimming | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Table tennis | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Tennis | ● ● | ● ● | |||||||||||||||

| Volleyball | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Water polo | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Weightlifting | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||

| Wrestling | ● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

● ● ● ● ● |

|||||||||||||

| Total gold medals | 10 | 17 | 12 | 17 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 20 | 28 | 19 | 7 | 18 | 14 | 21 | 30 | 18 | |

| Ceremonies | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Date | 19th Fri | 20th Sat | 21st Sun | 22nd Mon | 23rd Tue | 24th Wed | 25th Thu | 26th Fri | 27th Sat | 28th Sun | 29th Mon | 30th Tue | 31st Wed | 1st Thu | 2nd Fri | 3rd Sat | 4th Sun |

| July | August | ||||||||||||||||

Games

Opening ceremony

The ceremony began with a 60-second countdown, which included footage from all of the previous Olympic Games at twenty-two seconds. There was then a flashback to the closing ceremony of the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, showing the then president of the IOC, Juan Antonio Samaranch, inviting the athletes to compete in Atlanta in 1996. Then, spirits ascended in the northwest corner of the stadium, each representing one of the colors in the Olympic rings. The spirits called the tribes of the world which, after mixed percussion, formed the Olympic rings while the youth of Atlanta formed the number 100. Famed film score composer John Williams wrote the official overture for the 1996 Olympics, called "Summon the Heroes"; this was his second overture for an Olympic games, the first being "Olympic Fanfare and Theme" written for the 1984 Summer Olympics. Céline Dion performed David Foster's official 1996 Olympics song "The Power of the Dream", accompanied by Foster on the piano, the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and the Centennial Choir (comprising Morehouse College Glee Club, Spelman College Glee Club and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Chorus). Gladys Knight sang Georgia's official state song "Georgia on My Mind".

There was a showcase entitled "Welcome To The World", featuring cheerleaders, Chevrolet pick-up trucks, marching bands, and steppers, which highlighted the American youth and a typical Saturday college football game in the South, including the wave commonly produced by spectators in sporting events around the world. There was another showcase entitled "Summertime" which focused on Atlanta and the Old South, emphasizing its beauty, spirit, music, history, culture, and rebirth after the American Civil War. The ceremony also featured a memorable dance tribute to the athletes and to the goddesses of victory of the ancient Greek Olympics, using silhouette imagery. The accompanying music, "The Tradition of the Games", was composed by Basil Poledouris.[25]

Muhammad Ali lit the Olympic cauldron and later received a replacement gold medal for his boxing victory in the 1960 Summer Olympics. For the torch ceremony, more than 10,000 Olympic torches were manufactured by the American Meter Company and electroplated by Erie Plating Company. Each torch weighed about 3.5 pounds (1.6 kg) and was made primarily of aluminum, with a Georgia pecan wood handle and gold ornamentation.[26][27]

Closing ceremony

Sports

The 1996 Summer Olympic programme featured 271 events in 26 sports. Softball, beach volleyball and mountain biking debuted on the Olympic program, together with women's football and lightweight rowing.

|

|

|

|

In women's gymnastics, Ukrainian Lilia Podkopayeva became the all-around Olympic champion. Podkopayeva also won a second gold medal in the floor exercise final and a silver on the beam – becoming the only female gymnast since Nadia Comăneci to win an individual event gold after winning the all-round title in the same Olympics. Kerri Strug of the United States women's gymnastics team vaulted with an injured ankle and landed on one foot, winning the first women's team gold medal for the US. Shannon Miller won the gold medal on the balance beam event, the first time an American gymnast had won an individual gold medal in a non-boycotted Olympic games. The Spanish team won the first gold medal in the new competition of women's rhythmic group all-around. The team was formed by Estela Giménez, Marta Baldó, Nuria Cabanillas, Lorena Guréndez, Estíbaliz Martínez and Tania Lamarca.

Amy Van Dyken won four gold medals in the Olympic swimming pool, the first American woman to win four titles in a single Olympiad. Penny Heyns, swimmer of South Africa, won the gold medals in both the 100 metres and 200 metres breaststroke events. Michelle Smith of Ireland won three gold medals and a bronze in swimming. She remains her nation's most decorated Olympian. However, her victories were overshadowed by doping allegations even though she did not test positive in 1996. She received a four-year suspension in 1998 for tampering with a urine sample, though her medals and records were allowed to stand.

In track and field, Donovan Bailey of Canada won the men's 100 m, setting a new world record of 9.84 seconds at that time. He also anchored his team's gold in the 4 × 100 m relay. Michael Johnson won gold in both the 200 m and 400 m, setting a new world record of 19.32 seconds in the 200 m. Marie-José Pérec equaled Johnson's performance, although without a world record, by winning the rare 200 m/400 m double. Carl Lewis won his 4th long jump gold medal at the age of 35.

In tennis, Andre Agassi won the gold medal, which would eventually make him the first man and second singles player overall (after his eventual wife, Steffi Graf) to win the career Golden Slam, which consists of an Olympic gold medal and victories in the singles tournaments held at professional tennis' four major events (Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon, and US Open).

There were a series of national firsts realized during the Games. Deon Hemmings became the first woman to win an Olympic gold medal for Jamaica and the English-speaking West Indies. Lee Lai Shan won a gold medal in sailing, the only Olympic medal that Hong Kong ever won as a British colony (1842–1997). This meant that for the only time, the colonial flag of Hong Kong was raised to the accompaniment of the British national anthem "God Save the Queen", as Hong Kong's sovereignty was later transferred to China in 1997. The US women's football team won the gold medal in the first ever women's football event. For the first time, Olympic medals were won by athletes from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Burundi, Ecuador, Georgia, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Mozambique, Slovakia, Tonga, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. Another first in Atlanta was that this was the first Summer Olympics ever that not a single nation swept all three medals in a single event.

Records

Medal count

These are the top ten nations that won medals at the 1996 Games.

* Host nation (United States)

| Rank | Nation | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | 32 | 25 | 101 | |

| 2 | 26 | 21 | 16 | 63 | |

| 3 | 20 | 18 | 27 | 65 | |

| 4 | 16 | 22 | 12 | 50 | |

| 5 | 15 | 7 | 15 | 37 | |

| 6 | 13 | 10 | 12 | 35 | |

| 7 | 9 | 9 | 23 | 41 | |

| 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 25 | |

| 9 | 9 | 2 | 12 | 23 | |

| 10 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 27 | |

| Totals (10 nations) | 168 | 144 | 155 | 467 | |

Participating National Olympic Committees

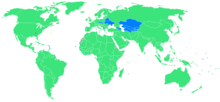

Blue = Participating for the first time. Green = Have previously participated. Yellow square is host city (Atlanta)

A total of 197 nations, all of the then-existing and recognised National Olympic Committees were represented at the 1996 Games, and the combined total of athletes was about 10,318.[28] Twenty-four countries made their Olympic debut this year, including eleven of the ex-Soviet countries that competed as part of the Unified Team in 1992. Russia participated in the Summer Olympics separately from the other former countries of the Soviet Union for the first time since 1912 (when it was the Russian Empire). Russia had been a member of the Unified Team at the 1992 Summer Olympics together with 11 post-Soviet states. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia competed as Yugoslavia.

The 14 countries making their Olympic debut were: Azerbaijan, Burundi, Cape Verde, Comoros, Dominica, Guinea-Bissau, Macedonia, Nauru, Palestinian Authority, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, São Tomé and Príncipe, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. The ten countries making their Summer Olympic debut (after competing at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer) were: Armenia, Belarus, Czech Republic, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Slovakia, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. The Czech Republic and Slovakia attended the games as independent nations for the first time since the breakup of Czechoslovakia, while the rest of the nations that made their Summer Olympic debut were formerly part of the Soviet Union.

Centennial Olympic Park bombing

The 1996 Olympics were marred by the Centennial Olympic Park bombing on July 27. Security guard Richard Jewell discovered the pipe bomb and immediately notified law enforcement and helped evacuate as many people as possible from the area before it exploded. Although Jewell's quick actions are credited for saving many lives, the bombing killed spectator Alice Hawthorne, wounded 111 others, and caused the death of Melih Uzunyol by heart attack. Jewell was later considered a suspect in the bombing but was never charged, and he was cleared in October 1996. In 2003, Eric Robert Rudolph was charged with and confessed to this bombing as well as the bombings of two abortion clinics and a gay bar. He stated "the purpose of the attack on July 27th was to confound, anger and embarrass the Washington government in the eyes of the world for its abominable sanctioning of abortion on demand."[29] He was sentenced to a life sentence at ADX Florence prison in Florence, Colorado.

Legacy

Preparations for the Olympics lasted more than six years and had an economic impact of at least $5.14 billion. Over two million visitors came to Atlanta, and approximately 3.5 billion people around the world watched at least part of the games on television. Although marred by the tragedy of the Centennial Olympic Park bombing, they were a financial success, due in part to TV rights contracts and sponsorships at record levels.[30]

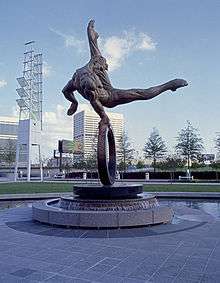

Beyond international recognition, the Games resulted in many modern infrastructure improvements. The mid-rise dormitories built for the Olympic Village, which became the first residential housing for Georgia State University (Georgia State Village), are now used by the Georgia Institute of Technology (North Avenue Apartments). As designed, Centennial Olympic Stadium was converted into Turner Field, which became the home of the Atlanta Braves Major League Baseball team from 1997 to 2016. The Braves' former home, Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium, was demolished in 1997 and the site became a parking lot for Turner Field; the Omni Coliseum was demolished the same year to make way for Philips Arena (since renamed State Farm Arena). The city's permanent memorial to the 1996 Olympics is Centennial Olympic Park, which was built as a focal point for the Games. The park initiated a revitalization of the surrounding area, and now serves as the hub for Atlanta's tourism district.[30]

In November 2016, a commemorative plaque was unveiled for Centennial Olympic Park to honor the 20th anniversary of the Games.[31][32]

After the Braves' departure from Turner Field, Georgia State University acquired the former Olympic Stadium and surrounding parking lots and reconfigured the stadium for a second time into Georgia State Stadium for its college football team.

The 1996 Olympics are the most recent edition of the Summer Olympics to be held in the United States. Los Angeles will host the 2028 Summer Olympics, 32 years after the games were held in Atlanta.[33]

Sponsors

The 1996 Summer Olympics relied heavily on commercial sponsorship. The Atlanta-based Coca-Cola Company was the exclusive provider of soft drinks at Olympics venues, and built an attraction known as Coca-Cola Olympic City for the Games.[34]

The Games were affected by several instances of ambush marketing—in which companies attempt to use the Games as a means to promote their brand, in competition with the exclusive, category-based sponsorship rights issued by the Atlanta organizing committee and the IOC (which grants the rights to use Olympics-related terms and emblems in marketing). The Atlanta organizing committee threatened legal actions against advertisers whose marketing implied an official association with the Games. Several non-sponsors set up marketing activities in areas near venues, such as Samsung (competing with Motorola), which ambushed the Games with its "'96 Expo".[35][36] The city of Atlanta had also licensed street vendors to sell products from competitors to Olympic sponsors.[37][38]

The most controversial ambush campaign was undertaken by Nike, Inc., which had begun an advertising campaign with aggressive slogans that mocked the Games' values, such as "Faster, Higher, Stronger, Badder", "If you're not here to win, you're a tourist", and "You don't win silver, you lose gold." The slogans were featured on magazine ads and billboards it purchased in Atlanta.[35] Nike also opened a pop-up store known as the Nike Center near the Athletes' Village, which distributed Nike-branded flags to visitors (presumably to be used at events).[39] IOC marketing director Michael Payne expressed concern for the campaign, believing that athletes could perceive them as being an insult to their accomplishments.[39] Payne and United States Olympic Committee's marketing director John Krimsky met with Howard Slusher, a subordinate of Nike co-founder Phil Knight. The meeting quickly turned aggressive, with Payne threatening that the IOC could pull accreditation for Nike employees, ban the display of its logos on equipment, and organize a press conference where silver medallists from the Games, as well as prominent Nike-sponsored athlete Michael Johnson (who attracted attention during the Games for wearing custom, gold-colored Nike shoes), would denounce the company. Faced with these threats, Nike agreed to retract most of its negative advertising and PR stunts.[39]

Reception

A report prepared by European Olympic officials after the Games was critical of Atlanta's performance in several key issues, including the level of crowding in the Olympic Village, the quality of available food, the accessibility and convenience of transportation, and the Games' general atmosphere of commercialism.[40] IOC vice-president Dick Pound defended criticism of the commercialization of these Games, stating that they still adhered to a historic policy barring the display of advertising within venues, and that "you have to look to the private sector for at least a portion of the funding, and unless you're looking for handouts, you're dealing with people who are investing business assets, and they have to get a return."[37]

The financial struggles faced by many later Games, such as the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, have led to more positive re-appraisals of the management of the 1996 Games. Former JPMorgan Chase president (and torchbearer) Kabir Sehgal noted that in contrast to many later Games, the 1996 Olympics were financially viable, had a positive economic impact on the city, and most of the facilities constructed for the Games still see use in the present day. Sehgal contrasted the Games' bid — a "grassroots" effort backed almost entirely by private funding, with the only significant public spending coming from infrastructure associated with the Games — to modern "top-down" bids, instigated by local governments and reliant on taxpayer funding, making them unpopular among citizens who may not necessarily be interested.[13]

At the closing ceremony, IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch said in his closing speech, "Well done, Atlanta" and simply called the Games "most exceptional." This broke precedent for Samaranch, who had traditionally labeled each Games "the best Olympics ever" at each closing ceremony, a practice he resumed at the subsequent Games in Sydney in 2000.[41]

In 1997, Athens, Greece would be awarded the 2004 Summer Olympics. Along with addressing the shortcomings of its 1996 bid, it was lauded for its efforts to promote the traditional values of the Olympic Games, which some IOC observers felt had been lost due to the over-commercialization of the 1996 Games. However, the 2004 Games heavily relied on public funding and eventually failed to make a profit, and contributed to the financial crisis in Greece.[42][43][44]

See also

- 1996 Summer Paralympics

- Olympic Games celebrated in the United States

- 1904 Summer Olympics – St. Louis

- 1932 Summer Olympics – Los Angeles

- 1932 Winter Olympics – Lake Placid

- 1960 Winter Olympics – Squaw Valley

- 1980 Winter Olympics – Lake Placid

- 1984 Summer Olympics – Los Angeles

- 1996 Summer Olympics – Atlanta

- 2002 Winter Olympics – Salt Lake City

- 2028 Summer Olympics – Los Angeles

- Summer Olympic Games

- Olympic Games

- International Olympic Committee

- List of IOC country codes

- Use of performance-enhancing drugs in the Olympic Games – 1996 Atlanta

Notes

- "Factsheet - Opening Ceremony of the Games of the Olympiad" (PDF) (Press release). International Olympic Committee. October 9, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 14, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Glanton, Dahleen. "Atlanta debates how golden it was". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "Live From PyeongChang". TvTechnology. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "Atlanta: 20 years later". Sports Business Journal. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- Payne, Michael (2006). Olympic turnaround: how the Olympic Games stepped back from the brink of Extinction to Become the Best Known Brand. Westport, Ct.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-99030-3.

- Weisman, Steven R. (September 19, 1990). "Atlanta Selected Over Athens for 1996 Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- Maloney, Larry (2004). "Atlanta 1996". In Finding, John E.; Pelle, Kimberly D. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 235–6. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- Edwards, Peter (July 24, 2015). "Toronto has made 5 attempts to host the Olympics. Could the sixth be the winner?" – via Toronto Star.

- Longman, Jere (August 3, 1997). "Athens Pins Olympic Bid to World Meet". The New York Times. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- "1996 Olympic Games". Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- "IOC Vote History". www.aldaver.com.

- The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was still in existence at the time of bidding for the 1996 Olympics, although it would cease to exist by the time of the 1996 Summer Olympic games

- "What Rio Should Have Learned From Atlanta's 1996 Summer Olympics". Fortune. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- Applebome, Peter (August 4, 1996). "So, You Want to Hold an Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- "The Olympic Legacy in Atlanta – [1999] UNSWLJ 38; (1999) 22(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 902". Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- July 18; 2016. "Atlanta Olympics: By The Numbers". Sports Business Daily. Retrieved March 20, 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Burbank, Matthew; et al. (2001). Olympic Dreams: The Impact of Mega Events on Local Politics. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 97.

- "Centennial Olympic Games" (PDF). la84foundation.org. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- "Atlanta Redefines Image With 'Come Celebrate Our Dream' Slogan". Seattle Times. February 19, 1995.

- "Congratulations Note from Billy Payne".

- "Remembering the Centennial Olympic Games in Savannah". City of Savannah. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- "Atlanta spinning 'Wheel' for sponsorship fortune". Washington Post. March 16, 1996. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "THAT `WHEEL OF FORTUNE' JUST KEEPS SPINNING ALONG". Deseret News. October 16, 1995. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "ProReview: Izzy's Quest for the Olympic Rings". GamePro. IDG (69): 46. April 1995.

- "Basil Poledouris Biography". Basil Poledouris website. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- Erie Times-News, "Erie Company's Olympic Work Shines", June 10, 1996, by Greg Lavine

- Plating and Surface Finishing Magazine, August 1996 Issue

- "Olympics OFFICIAL Recap". Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "On This Day: Bomb Explodes in Atlanta's Olympic Park". www.findingdulcinea.com. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Glanton, Dahleen (September 21, 2009). "Olympics' impact on Atlanta still subject to debate". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- "New historic marker for 1996 Games unveiled in Centennial Olympic Park". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- "Historical Marker planted for 1996 Centennial Olympic Games". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- "L.A. officially awarded 2028 Olympic Games". Los Angeles Times. September 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- Collins, Glenn. "Coke's Hometown Olympics;The Company Tries the Big Blitz on Its Own Turf". New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- "An Olympic-Size Ambush". Washington Post. July 17, 1996. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- "Samsung's Expo Gives It Olympic Exposure / And BellSouth is putting out COWS". SFGate. July 2, 1996. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "McGill's master of the rings". McGill Reporter. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "Olympic bid smacks into $10M hurdle". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "Rise of the pseudo-sponsors: A history of ambush marketing". SportPro. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- "Olympic Games: Maligned Atlanta meets targets". The Independent. United Kingdom. November 15, 1996. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- "Samaranch calls these Olympics 'best ever'". ESPN.com. October 1, 2000. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- https://www.cnbc.com/id/37484301

- Longman, Jere (September 6, 1997). "Athens Wins a Vote for Tradition, and the 2004 Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Anderson, Dave (September 7, 1997). "Athens Can Thank Atlanta for 2004 Games". New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1996 Summer Olympics. |

- "Atlanta 1996". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

- "Results and Medalists—1996 Summer Olympics". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee.

- Official Report Vol. 1 Digital Archive from the LA84 Foundation of Los Angeles

- Official Report Vol. 2 Digital Archive from the LA84 Foundation of Los Angeles

- Official Report Vol. 3 Digital Archive from the LA84 Foundation of Los Angeles

| Preceded by Barcelona |

Summer Olympic Games Atlanta XXVI Olympiad (1996) |

Succeeded by Sydney |