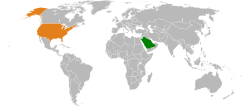

Saudi Arabia–United States relations

Saudi Arabia–United States relations refers to the bilateral relations between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States of America, which began in 1933 when full diplomatic relations were established and became formalized in the 1951 Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement. Despite the differences between the two countries—an ultraconservative Islamic absolute monarchy, and a secular, constitutional republic—the two countries have been allies. Former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama have close and strong relations with senior members of the Saudi Royal Family.[1]

| |

Saudi Arabia |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| The Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, Washington, D.C., United States | Embassy of the United States, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

| Envoy | |

| Saudi Arabian Ambassador to the United States Reema bint Bandar Al Saud | U.S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia John Abizaid |

Ever since the modern US–Saudi relationship began in 1945, the United States has been willing to overlook many of the kingdom's more controversial aspects as long as it maintained oil production and supported U.S. national security policies.[2] Since World War II, the two countries have been allied in opposition to Communism, in support of stable oil prices, stability in the oil fields and oil shipping of the Persian Gulf, and stability in the economies of Western countries where Saudis have invested. In particular the two countries were allies against the Soviets in Afghanistan and in the expulsion of Iraq from Kuwait in 1991. The two countries have been in disagreement with regard to the State of Israel, as well as the embargo of the U.S. and its allies by Saudi Arabia and other Middle East oil exporters during the 1973 oil crisis (which raised oil prices considerably), the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq (which Saudi Arabia opposed), aspects of the "War on Terror", and what many in the U.S. see as the pernicious influence of Saudi Arabia after the September 11 attacks. In recent years, particularly the Barack Obama administration, the relationship between the two countries became strained and witnessed major decline.[3][4][5] However, the relationship was strengthened by President Donald Trump's trip to Saudi Arabia in May 2017, which was his first overseas trip after becoming President of the United States.[6][7][8][9]

Despite the strong relationship between the two countries, opinion polls between the two nations show negative feelings between the American people and Saudi people in recent years, particularly American feelings towards the desert kingdom. A poll of Saudis by Zogby International (2002) and BBC (between October 2005 and January 2006) found 51% of Saudis had hostile feelings towards the American people in 2002;[10] in 2005/2006, Saudi public opinion was sharply divided with 38% viewing U.S. influence positively and 38% viewing U.S. influence negatively.[8] As of 2012, Saudi Arabian students form the 4th largest group of international students studying in the United States, representing 3.5% of all foreigners pursuing higher education in the US.[11] A December 2013 poll found 57% of Americans polled had an unfavorable view of Saudi Arabia and 27% favorable.[9]

In October 2018, the Jamal Khashoggi case[12] put the US into a difficult situation as Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, share a strong personal and official bond with Mohammad bin Salman. During an interview, Trump vowed to get to the bottom of the case and that there would be "severe punishment" if the Saudi kingdom is found to be involved in the disappearance or assassination of the journalist.[13] A vexed reply came from the Saudi Foreign Ministry saying if Saudi Arabia "receives any action, it will respond with greater action," citing the oil-rich kingdom's "influential and vital role in the global economy."[14] According to Turki Aldakhil, Saudi-owned news Channel, Al-Arabiya's general manager, this clash between the two countries would have a direct effect on the world economy. "If US sanctions are imposed on Saudi Arabia, we will be facing an economic disaster that would rock the entire world," Aldakhil said.[15]

After weeks of denial, Saudi Arabia accepted that Khashoggi died at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul during a "fistfight." Adel al-Jubeir described the journalist's death as a "murder" and a "tremendous mistake." But he denied the knowledge of whereabouts of the body.[16] Following the case, the US promised to revoke the visas of Saudi nationals responsible for Khashoggi's death.[17]

In November 2018, Trump defended Saudi Arabia, despite the country's involvement in the killing of Khashoggi. Experts in the Middle East believe that Congress could still put sanctions on some Saudi officials and the crown prince. However, even without the sanctions imposed, it is impossible for Mohammad bin Salman to visit Washington or have a direct relationship with the Trump administration.[18]

However, in November 2018, relations between the United States and Saudi Arabia re-strengthened when Trump nominated John Abizaid, a retired US army general who spoke Arabic as US ambassador to the country.[19] Saudi Arabia also brought a fresh face on board, appointing their first female ambassador, Princess Reema bint Bandar Al Saud, to help calm relations in the wake of Khashoggi's death.[20]

On 12 December 2018, United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations approved a resolution to suspend Yemen conflict-related sales of weapons to Saudi Arabia and impose sanctions on people obstructing humanitarian access in Yemen. Senator Lindsey Graham said, “This sends a global message that just because you’re an ally of the United States, you can’t kill with impunity. The relationship with Saudi Arabia is not working for America. It is more of a burden than an asset.”[21]

On 8 April 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that 16 Saudi nationals involved in Khashoggi's murder, including Mohammed bin Salman's close aid Saud al-Qahtani, have been barred from entering the US.[22][23]

Saudi Arabia is listed as the world's 27th largest export economy. Saudi Arabia has historically proven to be a successful harbor of trade, exemplified through statistics displaying a positive trade balance of nearly $32 billion in 2016.[24]

History

%2C_14_February_1945_(USA-C-545).jpg)

Early history (recognition)

Although King Abdulaziz Al Saud, Ibn Saud as an appellation, the founder of Saudi Arabia in 1901, had an excellent relationship with the British who defended Saudi Arabia from the Turks, he eventually developed even closer ties with the United States. After unifying his country, on September 28, 1928, Bin Saud set about gaining international recognition for Saudi Arabia. The United Kingdom was the first country to recognize Saudi Arabia as an independent state, as the British had provided protection of Saudi territories from the Turks for many years (Wafa, 2005). Saud also hoped to be recognized by the US, which at that time had no interest in Saudi Arabia. Initially, his efforts were rebuffed, but Washington eventually came around, promoted by the fact that Al Saud had obtained recognition from many nations. In May 1931 the U.S. officially recognized Saudi Arabia by extending full diplomatic recognition.[25][26] At the same time Ibn Saud granted a concession to the U.S. company, Standard Oil of California, allowing them to explore for oil in the country's Eastern Province, al-Hasa.[26] The company gave the Saudi government £35,000 and also paid assorted rental fees and royalty payments.

In November 1931, a treaty was signed by both nations which included favored nation status. The relationship was still weak, however, as America did not have an interest in establishing missions in Saudi Arabia: at the time, Saudi affairs were handled by the U.S. delegation in Cairo, Egypt, and did not send a resident ambassador to the country until 1943.[25]

The relationship between Saudi Arabia and the United States of America was economically strengthened in 1933, whereas Standard Oil of California was permitted a concession to explore the Saudi Arabian lands for oil. The subsidiary of this company, regarded as California Arabian Standard Oil Company, later deemed Saudi Aramco proved the exploration to be fruitful in 1938 after finding oil for the first time. The relationship between the two nations strengthened throughout the next decade, establishing a full diplomatic relationship through a symbolic acceptance of an American envoy in Saudi Arabia. President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with King Abdulaziz on the USS Murphy in 1945, formally solidifying the friendship between the two nations. Saudi Arabia proved their willingness to carry out relations by staying neutral in World War II as well as by allowing the Allied powers to utilize their air space.

Foundation of ARAMCO

The United States of America and Saudi Arabian trade relationship has long revolved around two central concepts: security and oil. Throughout the next two decades, signifying the 50s and 60s, relations between the two nations grew significantly stronger. In 1950 ARAMCO and Saudi Arabia agreed on a 50/50 profit distribution of the oil discovered in Saudi Arabia. In 1951 the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement was put into action, which allowed for the US arms trade to Saudi Arabia, along with a United States military training mission to be centered in the Saudi Land.[27] The relationship between these two nations, in terms of trade, continued to prove of high value until 1973 when King Faisal concluded that Saudi Arabia would take part of the oil embargo, which posed as the first disagreement between Saudi Arabia and the United States. In 1974 the oil embargo between the United States and Saudi Arabia was eradicated, which allowed for the United States and Saudi Arabia to sign military contracts amassing in two billion dollars in the fiscal year of 1975.[28]

After the promises that had been made by American oil explorers that Saudi Arabia could have a very good chance of finding oil, Al Saud accepted the American offer of exploration, because he was hoping that his land could have valuable materials that would support the country's economy. In May 1933 the California Arabian Standard Oil Company (CASOC), later called the Arab American Company (ARAMCO), had started the exploration in the country with large area to explore (Alnabrab, 2008). Although the imported oil was not very important for the U.S. at the time, Washington seemed hungry for the Saudi oil since their confidence in finding oil in Saudi Arabia had greatly grown, which resulted in stronger relations with Saudi Arabia (Irvine, 1981).

CASOC Struck oil near Dhahran, but production over the next several years remained low—only about 42.5 million barrels between 1941 and 1945; less than 1% of the output in the United States over the same time period. CASOC was later renamed the Arabian-American Oil Company (Aramco).

World War II

As the U.S.–Saudi relationship was growing slowly, World War II was beginning its first phase. The U.S. was deeply involved in World War II, and as a result, US-Saudi relations were put on the 'back burner'. This negligence left Saudi Arabia vulnerable to attack. Italy, an Axis power, bombed a CASOC oil installation in Dhahran crippling Saudi Arabia's oil production.[25] This attack left Bin Saud scrambling for to find an external power that would protect the country, fearing further attacks that would most likely cease the country's oil production and the flow of pilgrims coming into Makkah to perform Hajj, the base of the Saudi power and economy at that time (Wafa, 2005).

However, as World War II progressed, the United States began to believe that Saudi oil was of strategic importance. As a result, in the interest of national security, the U.S. began to push for greater control over the CASOC concession. On 16 February 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that "the defense of Saudi Arabia is vital to the defense of the United States", thereby making possible the extension of the Lend-Lease program to the kingdom. Later that year, the president approved the creation of the state-owned Petroleum Reserves Corporation, with the intent that it purchase all the stock of CASOC and thus gain control of Saudi oil reserves in the region. However, the plan was met with opposition and ultimately failed. Roosevelt continued to court the government, however—on 14 February 1945, he met with King Ibn Saud aboard the USS Quincy, discussing topics such as the countries' security relationship and the creation of a Jewish country in the Mandate of Palestine.

Bin Saud therefore approved the US's request to allow the U.S. air force to fly over and construct airfields in Saudi Arabia. The oil installations were rebuilt and protected by the U.S.,[25] the pilgrims' routes were protected (Wafa, 2005), and the U.S. gained a much needed direct route for military aircraft heading to Iran and the Soviet Union.[25] The first American consulate was opened in Dhahran in 1944.[29]

After World War II

In 1945, after World War II, Saudi citizens began to feel uncomfortable with U.S. forces still operating in Dhahran. In contrast, Saudi government and officials saw the U.S. forces as a major component of the Saudi military defense strategy.[30] As a result, Bin Saud balanced the two conflicts by increasing the demands on U.S. forces in Dhahran when the region was highly threatened and lowering it when the danger declined (Alnabrab, 1994). At this time, due to the start of the Cold War, the U.S. was greatly concerned about Soviet communism and devised a strategy of 'containing' the spread of communism within Arabian Peninsula, putting Saudi security at the top of Washington's list of priorities.[31] Harry S. Truman's administration also promised Bin Saud that he would protect Saudi Arabia from Soviet influence. Therefore, the U.S. increased its presence in the region to protect its interest and its allies.[30] The security relationship between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. was therefore greatly strengthened at the start of the 'cold war'.[32]

In 1950, Saudi Arabia and Aramco agreed to a 50–50 profit-sharing arrangement.

King Saud comes to power (1953)

In the late 1950s, King Saud, the eldest son of King Abdulaziz, came to power after his father's death. During Saud's time the U.S.–Saudi relations had faced many obstacles concerning the anti-communism strategy. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's new anti-Soviet alliance combined most of "the kingdom's regional rivals and foes", which heightened Saudi suspicions.[25] For this reason, in October 1955, Saud had joined the pro-Soviet strategy with Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser.[30] Furthermore, Saud dismissed the U.S. forces and replaced them by Egyptian forces. Thus, this act had sparked and innovated a new and a large conflict in the relationship. But in 1956, during the Suez crisis, Saud began to cooperate with the U.S. again after Eisenhower's opposition of the Israeli, British, and French plan to seize the canal. Eisenhower opposed the plan because of anti-Soviet purposes, but King Saud had admired the act and decided to start cooperating with the U.S.[30] As a result, Egyptian power greatly declined while US-Saudi relations were simultaneously improving.

Cold War and Soviet containment

In 1957, Saud decided to renew the U.S. base in Dhahran. In less than a year, after the Egyptian–Syrian unification in 1958, Egypt's pro-Soviet strategy had returned to power. Saud had once again joined their alliance, which declined the US-Saudi relationship to a fairly low point especially after he announced in 1961 that he changed his mind on renewing the U.S. base.[33] In 1962, however, Egypt attacked Saudi Arabia from bases in Yemen during the 1962 Yemeni revolution because of Saudi Arabia's Anti-revolution propaganda, which made Saud seek the U.S. support. President John F. Kennedy immediately responded to Saud's request by sending U.S. warplanes in July 1963 to the war zone to stop the attack which was putting U.S. interests at risk.[30] At the end of the war, shortly before Prince Faisal became king, the relationship rebuilt itself to become healthy again.[33]

As the United Kingdom withdrew from the Persian Gulf region in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the U.S. was reluctant to take on new security commitments. Instead, the Nixon administration sought to rely on local allies to "police" American interests (see Nixon Doctrine). In the Persian Gulf region, this meant relying on Saudi Arabia and Iran as "twin pillars" of regional security. Whereas in 1970 the U.S. provided less than $16 million to Saudi Arabia in military aid, that number increased to $312 million by 1972.[34] As part of the "twin pillars" strategy, the U.S. also attempted to improve relations between the Saudis and the Iranians, such as by persuading Iran to remove its territorial claim to Bahrain.[35]

Oil embargo and energy crises

In November 1964, Faisal became the new king after the conflicts he had with his brother Saud, the erstwhile king. The US, on the other hand, was not sure about the outcome of such unplanned change in the Saudi monarchy. Faisal, however, continued the cooperation with the US until October 20, 1973. Then came the low point of the relationship before 9/11, as Faisal decided to contribute in an oil embargo against the US and Europe in favor of the Arab position during the Yom Kippur War. That caused an energy crisis in the US.

"America's complete Israel support against the Arabs makes it extremely difficult for us to continue to supply the United States with oil, or even remain friends with the United States," said Faisal in an interview with international media.[36]

Despite the tensions caused by the oil embargo, the U.S. wished to resume relations with the Saudis. Indeed, the great oil wealth accumulated as a result of price increases allowed the Saudis to purchase large sums of American military technology. The embargo was lifted in March 1974 after the U.S. pressured Israel into negotiating with Syria over the Golan Heights. Three months later, "Washington and Riyadh signed a wide-ranging agreement on expanded economic and military cooperation." In the 1975 fiscal year, the two countries signed $2 billion worth of military contracts, including an agreement to send Saudi Arabia 60 fighter jets.[37] The Saudis also argued (partially on behalf of American desires) to keep OPEC price increases in the mid-1970s lower than Iraq and Iran initially wanted.[34] As part of the "twin pillars" strategy, the U.S. also attempted to improve relations between the Saudis and the Iranians, such as by persuading Iran to remove its territorial claim to Bahrain.[38]

The Saudis' increase of oil production to stabilize the oil price and the support of anti-communism have all contributed to closer relations with the U.S.[33] In January 1979, the U.S. sent F-15 fighters to Saudi Arabia for further protection from communism.[33] Furthermore, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia were both supporting anti-communist groups in Afghanistan and struggling countries, one of those groups later became known as the Al-Qaida terrorist organization.[39]

Government purchases

After the Cold War the U.S.–Saudi relations were improving. The U.S. and U.S. companies were actively engaged and paid handsomely for preparing and administrating the rebuilding of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia transferred $100 billion to the United States for administration, construction, weapons, and in the 1970s and 1980s higher education scholarships to the U.S.[40] During that era the U.S. built and administrated numerous military academies, navy ports, and Air Force military airbases. Many of these military facilities were influenced by the U.S., with the needs of cold war aircraft and deployment strategies in mind. Also the Saudis purchased a great deal of weapons that varied from F-15 war planes to M1 Abrams main battle tanks that later proved useful during the Gulf War.[40] The U.S. pursued a policy of building up and training the Saudi military as a counterweight to Shiite extremism and revolution following the revolution in Iran. The U.S. provided top of the line equipment and training, and consulted the Saudi government frequently, acknowledging them as the most important Islamic leader in that part of the world, and a key player in the U.S. security strategy.

The Gulf War

Relations between the two nations solidified even further past the point of the oil embargo, whereas the United States of America sent nearly 500,000 soldiers to Saudi Arabia in attempt to aid in protection against Iraq.[41] Following Operation Desert Shield, which was a response by President George H. W. Bush to Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990, America kept 5,000 troops in Saudi Arabia in order to maintain their protection and trade relations.[42]

Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 led to the Gulf War, during which the security relationship between the US and Saudi Arabia was greatly strengthened. Concurrently with the US invasion, King Fahd declared war against Iraq. The U.S. was concerned about the safety of Saudi Arabia against Saddam's intention to invade and control the oil reserves in the region. As a result, after King Fahd's approval, President Bush deployed a significant amount of American military forces (up to 543,000 ground troops by the end of the operation) to protect Saudi Arabia from a possible Iraqi invasion; this operation was called Desert Shield. Furthermore, the U.S. sent additional troops in operation Desert Storm with nearly 100,000 Saudi troops sent by Fahad to form a US-Saudi army alliance, along with troops from other allied countries, to attack Iraqi troops in Kuwait and to stop further invasion.[43] During Operation Desert Storm Iraqi troops were defeated within four days, causing the Iraqis to retreat back to Iraq.

Operation Southern Watch

Since the Gulf War, the U.S. had a continued presence of 5,000 troops stationed in Saudi Arabia – a figure that rose to 10,000 during the 2003 conflict in Iraq.[44] Operation Southern Watch enforced the no-fly zones over southern Iraq set up after 1991, and the country's oil exports through the shipping lanes of the Persian Gulf are protected by the US Fifth Fleet, based in Bahrain.

The continued presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia was one of the stated motivations behind the September 11 attacks,[44] as well as the Khobar Towers bombing.[45] In 2003, the U.S. withdrew most of its troops from Saudi Arabia, though one unit still remains.

2010 U.S. arms sale to Saudi Arabia

On October 20, 2010, U.S. State Department notified Congress of its intention to make the biggest arms sale in American history – an estimated $60.5 billion purchase by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The package represents a considerable improvement in the offensive capability of the Saudi armed forces.[46]

The U.S. was keen to point out that the arms transfer would increase "interoperability" with U.S. forces. In the 1990–1991 Gulf War, having U.S.-trained Saudi forces, along with military installations built to U.S. specifications, allowed the American armed forces to deploy in a comfortable and familiar battle environment. This new deal would increase these capabilities, as an advanced American military infrastructure is about to be built.[47]

Foreign policy

Upon becoming regent in 2005, King Abdullah's first foreign trip was to China. In 2012 A Saudi-Chinese agreement to cooperate in the use of atomic energy for peaceful purposes was signed. Abdullah also welcomed Russian president Vladimir Putin to Riyadh in 2007, awarding him the kingdom's highest honor, the King Abdul Aziz Medal. Russia and Saudi concluded a joint venture between Saudi ARAMCO and LUKOIL to develop new Saudi gas fields. [48] [49]

Rift

.jpg)

Alwaleed bin Talal warned several Saudi ministers in May 2013 that shale gas production in the U.S. would eventually pose a threat to the kingdom's oil-dependent economy. Despite this, the two countries still maintained a positive relationship.[50]

In October 2013, Saudi intelligence chief Prince Bandar bin Sultan suggested a distancing of Saudi Arabia–United States relations as a result of differences between the two countries over the Syrian civil war and diplomatic overtures between Iran and the Obama administration.[51] The Saudis rejected a rotating seat on the UN Security Council that month (despite previously campaigning for such a seat), in protest of American policy over those issues.[52]

Saudi Arabia was cautiously supportive of a Western-negotiated interim agreement with Iran over its nuclear program. President Obama called King Abdullah to brief him about the agreement, and the White House said the leaders agreed to "consult regularly" about the U.S.'s negotiations with Iran.[53]

Controversies

.jpg)

First conflict

While the U.S.–Saudi relationship was growing, their first conflict began when the disorder broke between the Jews and Arabs in April 1936 in the British-administrated Palestine mandate. The U.S. favored the establishment of an independent Israeli state, but Saudi Arabia on the other hand, the leading nation in the Islamic and Arab world were supporting the Arab position which sparked up their first conflict. In other words, the U.S. oil interest in Saudi Arabia could be held hostage depending on the circumstances of the conflict.[25] U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt sent the king a letter indicating that it is true that the U.S. supports the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, but it is not in any way responsible for the establishment (Alnabrab, 2008). Bin Saud was convinced by the message that the U.S.–Saudi relations had begun to run smooth again. Moreover, in March 1938, CASCO made a big oil discovery in Saudi Arabia booming the oil industry in the country and coincidentally the U.S. became more interested in Saudi oil. As a result, on February 4, 1940, as the World War II was approaching, the U.S. had established a diplomatic presence in Saudi Arabia to have closer relations with the Saudis and to protect it from enemy hand; Bert Fish, former ambassador in Egypt was elected as the U.S. ambassador in Jeddah.[32]

Petrodollar power

.jpg)

The United States dollar is the de facto world currency.[54] The petrodollar system originated in the early 1970s in the wake of the Bretton Woods collapse. President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, feared that the abandonment of the international gold standard under the Bretton Woods arrangement (combined with a growing US trade deficit, and massive debt associated with the ongoing Vietnam War) would cause a decline in the relative global demand of the U.S. dollar. In a series of meetings, the United States and the Saudi royal family made an agreement. The United States would offer military protection for Saudi Arabia's oil fields, and in return the Saudi's would price their oil sales exclusively in United States dollars (in other words, the Saudis were to refuse all other currencies, except the U.S. dollar, as payment for their oil exports).[55][56]

September 11 attacks

On September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C. and in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania by four hijacked airplanes killed 2,977 victims and cost an estimated $150 billion in property and infrastructure damage and economic impact, exceeding the death toll and damage caused by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor 60 years earlier.[57] 15 of the 19 hijackers in the attacks came from Saudi Arabia, as did the leader of the hijackers' organization, (Osama bin Laden). In the U.S., there followed considerable negative publicity for, and scrutiny of, Saudi Arabia and its teaching of Islam,[58] and a reassessing of the "oil-for-security" alliance with the Al Saud.[59][60] A 2002 Council on Foreign Relations Terrorist Financing Task Force report found that: "For years, individuals and charities based in Saudi Arabia have been the most important source of funds for al-Qaeda. And for years, Saudi officials have turned a blind eye to this problem."[61]

In the backlash against Saudi Arabia and Wahhabism, the Saudi government was portrayed in the media, Senate hearings, and elsewhere as

a sort of oily heart of darkness, the wellspring of a bleak, hostile value system that is the very antithesis of our own. America's seventy-year alliance with the kingdom has been reappraised as a ghastly mistake, a selling of the soul, a gas-addicted alliance with death.[62]

There was even a proposal at the Defense Policy Board, (an arm of Department of Defense) to consider `taking Saudi out of Arabia` by forcibly seizing control of the oil fields, giving the Hijaz back to the Hashemites, and delegating control of Medina and Mecca to a multinational committee of moderate, non-Wahhabi Muslims.[63]

In Saudi Arabia itself, anti-American sentiment was described as "intense"[64] and "at an all-time high".[65]

A survey taken by the Saudi intelligence service of "educated Saudis between the ages of 25 and 41" taken shortly after the 9/11 attacks "concluded that 95 percent" of those surveyed supported Bin Laden's cause.[66] (Support for Bin Laden reportedly waned by 2006 and by then, the Saudi population become considerably more pro-American, after Al-Qaeda linked groups staged attacks inside Saudi Arabia.[67]) The proposal at the Defense Policy Board to `take Saudi out of Arabia` was spread as the secret US plan for the kingdom.[68]

In October 2001, The Wall Street Journal reported that Crown Prince Abdullah sent a critical letter to U.S. President George W. Bush on August 29: "A time comes when peoples and nations part. We are at a crossroads. It is time for the United States and Saudi Arabia to look at their separate interests. Those governments that don't feel the pulse of their people and respond to it will suffer the fate of the Shah of Iran."[69]

For over a year after 9/11 Saudi Minister of the Interior (a powerful post whose jurisdiction included domestic intelligence gathering), Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, insisted that the Saudi hijackers were dupes in a Zionist plot. In December 2002, a Saudi government spokesman declared that his country was the victim of unwarranted American intolerance bordering on hate.[70]

In 2003, several terror attacks targeted U.S. compounds, the Saudi ministry of interior, and several other places occurred inside Saudi Arabia. As a result of these attacks, the U.S. decided to redevelop Saudi law enforcement agencies by providing them with anti-terrorism education, the latest technologies, and by giving them a chance to interact with U.S. law enforcement agencies to gain efficient knowledge and power needed to handle terrorist cases and to enforce anti-terrorist laws.[30]

American politicians and media have accused the Saudi government of supporting terrorism and tolerating a jihadist culture,[71] noting that Osama bin Laden and fifteen out of the nineteen (or 78 percent of) 9/11 hijackers were from Saudi Arabia.[72]

Although some analysts have speculated that Osama bin Laden, who in 1994 had his Saudi nationality revoked and expelled from Saudi Arabia, had chosen 15 Saudi hijackers on purpose to break up the U.S.–Saudi relations, as the U.S. was still suspicious of Saudi Arabia (PBS Frontline, 2005). The Saudi's decided to cooperate with the U.S. on the war on terror. "Terrorism does not belong to any culture, or religion, or political system", said King Abdullah as the opening address of the Counter-terrorism International Conference (CTIC) held in Riyadh in 2005. The cooperation grew broader covering financial, educational, technological aspects both in Saudi Arabia and Muslim-like countries to prevent pro-Al-Qaeda terrorists' activities and ideologies. "It is a high time for the Ulma (Muslim Scholars), and all thinkers, intellectuals, and academics, to shoulder their responsibilities towards the enlightenment of the people, especially the young people, and protect them from deviant ideas" said Sheikh Saleh bin Abdulaziz Alsheikh, Minister of Islamic Affairs, in the CTIC.

Almost all members of the CTIC agreed that Al-Qaeda target less educated Muslims by convincing them that they are warriors of God, but they really convince them to only accomplish their political goals. Three years after the Saudi Serious and active role on anti-terrorist, Al-Qaeda began launching multiple attacks targeting Saudi government buildings and U.S. compounds in Saudi grounds (Alshihry, 2003). Their attacks exhibit their revenge against Saudi Arabia's cooperation with the U.S. trying to stop further US–Saudi anti-terrorist movements and trying to corrode the US-Saudi relationship and to annihilate it.

After these changes, the Saudi government was more equipped in preventing terrorist activities. They caught a large number of Saudi terrorists and terrorists from other countries (some of them American) that had connections with al-Qaeda in one way or another (U.S. Department of State 2007). Some of these criminals held high rank in terrorist society, which helped diffuse many terrorist cells (Alahmary, 2004). In a matter of months, Saudi law enforcement officials were successfully able to stop and prevent terrorist activities. Also, they were successful in finding the source of terrorist financing.

In March 2018, a US judge formally allowed a suit to move forward against Saudi Arabia government brought by 9/11 survivors and victim's families.[73]

Child abduction

The international abduction of American children to Saudi Arabia provoked sustained criticism and resulted in a Congressional hearing in 2002 where parents of children held in Saudi Arabia gave impassioned testimony related to the abduction of their children. Washington-based Insight ran a series of articles on international abduction during the same period highlighting Saudi Arabia a number of times.[74][75][76][77]

Allegations of funding terrorism

According to a 2009 U.S. State Department communication by Hillary Clinton, United States Secretary of State, (disclosed as part of the Wikileaks U.S. 'cables leaks' controversy in 2010) "donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide".[78] Part of this funding arises through the zakat (an act of charity dictated by Islam) paid by all Saudis to charities, and amounting to at least 2.5% of their income. Although many charities are genuine, others allegedly serve as fronts for money laundering and terrorist financing operations. While many Saudis contribute to those charities in good faith believing their money goes toward good causes, it has been alleged that others know full well the terrorist purposes to which their money will be applied.[79]

In September 2016, the Congress passed the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act that would allow relatives of victims of the September 11 attacks to sue Saudi Arabia for its government's alleged role in the attacks.[80][81][82][83]

Saudi Arabia was involved in the CIA-led Timber Sycamore covert operation to train and arm Syrian rebels. Some American officials worried that Syrian rebels being supported had ties to al-Qaeda.[84][85] In October 2015, Saudi Arabia delivered 500 U.S.-made TOW anti-tank missiles to anti-Assad rebels.[86] Reports indicate that some TOW missiles have ended up in the hands of al-Qaeda in Syria and Islamic State.[87][88]

2017 arms deal and war in Yemen

Significant numbers of Americans have criticized the conduct of Saudi Arabia in its ongoing intervention in the Yemeni Civil War, including alleged war crimes such as bombing of hospitals, gas stations, water infrastructure, marketplaces and other groups of civilians, and archaeological monuments; declaring the entire Saada Governorate a military target; use of cluster bombs; and enforcing a blockade of food and medical supplies that has triggered a famine. Critics oppose U.S. support of Saudi Arabia for this operation, which they say does not benefit the national security interests of the United States, and they object to the United States selling arms to Saudi Arabia for use in Yemen.[89]

The approval of the 2017 arms deal was opposed by various lawmakers, including GOP Senators Mike Lee, Rand Paul, Todd Young and Dean Heller along with most Democrat Senators who voted to advance the measure in order to block the sale, citing the human rights violations by Saudi Arabia in the Yemeni Civil War.[90][91] Among the senators who voted against moving the measure to block the sale were Democratic Senators Joe Donnelly, Claire McCaskill, Bill Nelson, Joe Manchin and Mark Warner along with top Republicans, including Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Bob Corker and John McCain.[92]

Tulsi Gabbard, a Democratic Representative from Hawaii, criticized the move, saying that Saudi Arabia is "a country with a devastating record of human rights violations at home and abroad, and a long history of providing support to terrorist organizations that threaten the American people".[93][94] Rand Paul introduced a bill to try to block the plan calling it a "travesty".[95][96][97]

U.S. Senator Chris Murphy accused the United States of complicity in Yemen's humanitarian crisis, saying: "Thousands and thousands inside Yemen today are dying. ... This horror is caused in part by our decision to facilitate a bombing campaign that is murdering children and to endorse a Saudi strategy inside Yemen that is deliberately using disease and starvation and the withdrawal of humanitarian support as a tactic."[98]

Khashoggi killing

.jpg)

In October 2018, serious allegations were put on Saudi for murdering a Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urged Saudi Arabia to "support a thorough investigation" regarding the disappearance and "to be transparent about the results."[99] Trump said, "We cannot let this happen to reporters, to anybody. We're demanding everything. We want to see what's going on there."[100]

Lindsey Graham, a senior Republican senator's reaction was stern, as he said "there would be hell to pay" if Saudi is involved in the murder of Khashoggi. He further added, "If they're this brazen it shows contempt. Contempt for everything we stand for, contempt for the relationship."[101]

Freedom of religion

Ambassador at Large Sam Brownback condemned the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for its religious freedom abuses, on the release of 2018 Report on International Religious Freedom by the State Department. Brownback called Saudi as "one of the worst actors in the world on religious persecution" and hoped to see “actions take place in a positive direction”. The report details discrimination against and maltreatment of Shiite Muslims in Saudi Arabia that includes the mass execution of 34 individuals in April 2019, out of which a majority were Shiite Muslims.[102]

2019 arms legislation

In the wake of a declining human rights record, on 17 July 2019, lawmakers in Washington backed a resolution to block the sale of precision-guided munitions to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.[103] However, President Donald Trump has indicated of vetoing the resolution that denies billions of dollars of weapon sale to the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen where thousands have been killed in the 4-year long war.[104][105]

2016 U.S. presidential election

In August 2016, Donald Trump Jr. had a meeting with an envoy representing Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince and de facto ruler Mohammad bin Salman, and Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi. The envoy offered help to the Trump presidential campaign,[106] which would be illegal under U.S. law. The meeting included Lebanese-American lobbyist George Nader, Joel Zamel, an Israeli specialist in social media manipulation, and Blackwater founder Erik Prince.[106][107]

Special Counsel Robert Mueller investigated the Trump campaign's possible ties to Saudi Arabia.[108] Lebanese-American businessman Ahmad Khawaja claimed that Saudi Arabia and UAE illegally funnelled millions of dollars into the Trump's campaign.[109]

In April 2017, U.S. President Donald J. Trump attempted to repair the United States' relationship with Saudi Arabia by having the US Defense Secretary visit Saudi Arabia. Trump has stated that he aims to help and assist Saudi Arabia in terms of military protection in order to receive beneficial economic compensation for the United States in return.[27]

Pensacola shooting

On December 6, 2019, an aviation student from Saudi Arabia Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani shot three people dead and injured eight others at US Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida.[110] This attack is concluded as a terrorist attack by FBI following the investigation. Alshamrani himself is a second lieutenant in the Royal Saudi Air Force who was participating in a training program sponsored by the Pentagon as part of a security cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia. Later, the Navy suspended flight training for all Saudi military aviation students pending the results of the FBI investigation.[111]

Florida governor Ron DeSantis placed a large amount of blame and need for compensation on the Saudi government, stating "They [Saudi Arabia] are going to owe a debt here given that this is one of their individuals."[112]

Post-9/11 relationship

.jpg)

Saudi Arabia engaged the Washington, D.C., lobbying firm of Patton Boggs as registered foreign agents in the wake of the public relations disaster when knowledge of the identities of suspected hijackers became known. They also hired the PR and lobbying firm Qorvis for $14 million a year. Qorvis engaged in a PR frenzy that publicized the "9/11 Commission finding that there was 'no evidence that the Saudi government as an institution or senior Saudi officials individually funded [Al Qaeda]'—while omitting the report's conclusion that 'Saudi Arabia has been a problematic ally in combating Islamic extremism.'"[113][114]

According to at least one journalist (John R. Bradley), the ruling Saudi family was caught between depending for military defense on the United States, while also depending for domestic support on the Wahhabi religious establishment, which as a matter of religious doctrine "ultimately seeks the West's destruction", including that of its ruler's purported ally—the US.[115] During the Iraq War, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Saud Al-Faisal, criticized the U.S.-led invasion as a "colonial adventure" aimed only at gaining control of Iraq's natural resources.[116] But at the same time, Bradley writes, the Saudi government secretly allowed the US military to "essentially" manage its air campaign and launch special operations against Iraq from inside Saudi borders, using "at least three" Saudi air bases.[117]

The two nations cooperate and share information about al-Qaeda (Alsheikh 2006) and leaders from both countries continue to meet to discuss their mutual interests and bilateral relations.[118]

Saudi Arabia and the U.S. are strategic allies,[119][120] and since President Obama took office in 2009, the U.S. has sold $110 billion in arms to Saudi Arabia.[121][122] The National Security Agency (NSA) in 2013 began cooperating with the Saudi Ministry of Interior in an effort to help ensure "regime continuity". An April 2013 top secret memo shows the agency's program of providing "direct analytic and technical support" to the Saudis on "internal security" matters. The CIA had already been gathering intelligence for the regime long before.[123]

In January 2015, after the death of King Abdullah, the White House and President Obama praised him as a leader and mentioned "the importance of the U.S.-Saudi relationship as a force for stability and security in the Middle East and beyond."[124]

In March 2015, President Barack Obama declared that he had authorized U.S. forces to provide logistical and intelligence support to the Saudis in their military intervention in Yemen, establishing a "Joint Planning Cell" with Saudi Arabia.[126] U.S. government lawyers have considered whether the United States is legally a "co-belligerent" in the conflict. Such a finding would oblige the U.S. to investigate allegations of war crimes by the Saudi coalition, and U.S. military personnel could be subject to prosecution.[127][128]

American journalist Glenn Greenwald wrote in October 2016: "From the start of the hideous Saudi bombing campaign against Yemen 18 months ago, two countries have played active, vital roles in enabling the carnage: the U.S. and U.K. The atrocities committed by the Saudis would have been impossible without their steadfast, aggressive support."[129]

In September 2016, Senators Rand Paul and Chris Murphy worked to prevent the proposed sale of $1.15 billion in arms from the U.S. to Saudi Arabia.[130] The U.S. Senate voted 71 to 27 against the Murphy–Paul resolution to block the U.S.–Saudi arms deal.[131]

While the trade based relationship between the United States of America and Saudi Arabia is one that is vastly affected by political disagreements and positions, the trade has yet to cease since its conception. Relations between the two nations have never come to a complete halt throughout history due to the economic advantages both nations gain from one another. Statistically, the trade balance, using 2016 as a benchmark year, has declined to a deficit of 2.5 billion dollars over the 2017 year, popular opinion is that this exemplifies strong future relations between the two nations through the political and militaristic common grounds the United States has been developing with Saudi Arabia.[24] Many experts believe the United States of America and Saudi Arabia are almost 'perfect' for trade due to oil being an essential commodity to the American people and the overall economy of the United States.

In January 2017, U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis "reaffirmed the importance of the U.S.-Saudi Arabia strategic relationship".[132] Mattis has voiced support for a Saudi Arabian-led military campaign against Yemen's Shiite rebels.[133][134] He asked the President to remove restrictions on U.S. military support for Saudi Arabia.[135] On 10 February 2017, CIA director Mike Pompeo awarded the Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Nayef with the CIA's "George Tenet" Medal.[136]

Trade relations

Energy and oil

Saudi Arabia has been an enticing trade partner with the United States from the early 20th century. The biggest commodity traded between the two nations is oil. The strength of the relationship is notoriously attributed to the United States' demand on oil throughout the post modern era, approximately 10,000 barrels of petroleum are imported daily to United States since 2012 ("U.S. Total Crude Oil and Products Imports").[137] Saudi Arabia has consistently been in need of weapons, reinforcement, and arms due to the consistent rising tensions throughout the Middle East during the late 20th century and early 21st century. Post 2016, the United States of America has continued to trade with Saudi Arabia mainly for their oil related goods. The top exports of Saudi Arabia are Crude Petroleum ($96.1B), Refined Petroleum ($13B), Ethylene Polymers($10.1B), Propylene Polymers ($4.93B) and Ethers ($3.6B), using the 1992 revision of the HS (Harmonized System) classification.[24] Its top imports are Cars ($11.8B), Planes, Helicopters, and/or Spacecraft ($3.48B), Packaged Medicaments ($3.34B), Broadcasting Equipment ($3.27B) and Aircraft Parts ($2.18B)".[138]

Recent years

In the year 2017, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was the United States of America's 20th ranked export market across the globe and ranked 21st in import markets.[24] The most prominent goods set forth as exports to Saudi Arabia in the designated year (2017) were "aircraft ($3.6 billion), vehicles ($2.6 billion), machinery ($2.2 billion), electrical machinery ($1.6 billion), and arms and ammunition ($1.4 billion).[139] In terms of statistics, the United States - Saudi Arabian trade declined approximately nine percent in U.S. exports in 2017 compared to the year prior; however, 2017 exemplified great reparation of the relationship through a 57% increase of exports from 2007.[139] Imports between the two nations increased approximately 11 percent from 2017 to 2018, which is an overall decline of 47% since the year fiscal 2007.[139] The entities that the United States of America seeks to import from Saudi Arabia has hardly changed over the years: "The top import categories (2-digit HS) in 2017 were: mineral fuels ($18 billion), organic chemicals ($303 million), special other (returns) ($247 million), aluminum ($164 million), and fertilizers ($148 million)".[139]

Controversies

Saudi Arabia and the United States of America have never fully eliminated their trading agreements however the relationship has experience consistent disagreements through its history from its conception. In the height of the Syrian Civil War, which started in March 2011, Saudi Arabia expressed disapproval of the United States lack of action in eradicating Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.[140] The United States' has consistently expressed disapproval of the treatment of Saudi Arabian women within the confines of the Kingdom. The famous criticisms of the early 21st century behind the relationship between the two countries is due to the mix of the disregard of the aforementioned issues and the public knowledge that trade between Saudi Arabia and the United States has trended upwards in the post 9/11 world. In recent years, the imports and exports of U.S- Saudi trades have not shown a percentage increase each year, where it topped out around 2012 and has been in slight fluctuation since, but the overall trend of trade has shown a positive slope.[24] In 2001: U.S. exports were at $5,957.60 and imports were at $13,272.20 (in millions of U.S. dollars) whereas, controversially as it is believed, in 2012 the United States witnessed $17,961.20 in exports and $55,667.00 in imports.[24]

The most damaging occurrence to ever affect the trade relationship between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. occurred on September 11, 2001 due to Saudi Arabia's believed involvement in the 9/11 attacks that occurred in multiple cities throughout the United States. Tensions also rose between the two nations throughout Barack Obama's Presidency due to the United States agreement in the Iran, when the U.S. removed oil sanctions on Iran and allowed them to sell their oil to the U.S. The relationship was also hindered by the oil market crash of 2014, propelled by increased shale oil production in the United States, which in turn caused Saudi Arabian exports of oil to decrease by nearly fifty percent.[27] Oil went from around $110 a barrel prior to the 2014 crash, to about $27 a barrel by the beginning of 2016.[27] This relationship worsened after the U.S. legislation passed a bill of a that allowed victims of the 9/11 attacks to sue the Saudi Arabian government for their losses in 2016.[141]

In 2019, US Federal law enforcement officials launched an investigation into cases involving the disappearance of Saudi Arabian students from Oregon and other parts of the country, while they faced charges in the US. Amidst the investigation, it has been speculated that the Saudi government helped the students in escaping from the US.[142][143] In October 2019, the U.S. Senate passed a bill by Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon, requiring the FBI to declassify any information regarding Saudi Arabia’s possible role. Oregon officials demand extradition of these suspects by Saudi Arabia since they were involved in violent crimes causing bodily harm and death.[144]

Notable diplomatic visits

After President George W. Bush's two visits to Saudi Arabia in 2008—which was the first time a U.S. president visited a foreign country twice in less than four months—and King Abdullah's three visits to the US—2002, 2005 and 2008—the relations have surely reached their peak. The two nations have expanded their relationship beyond oil and counter terrorism efforts. For example, King Abdullah has allocated funds for young Saudis to study in the United States.[145] One of the most important reasons that King Abdullah has given full scholarships to young Saudis is to give them western perspective and to impart a positive impression of Saudi Arabia on the American people (Alslemy, 2008). On the other hand, President Bush discussed the world economic crisis and what the U.S.–Saudi relationship can do about it (Tabassum, 2008). During meetings with the Saudis, the Bush Administration took the Saudi policies very seriously because of their prevalent economic and defensive presence in the region and its great media influence on the Islamic world (Al Obaid 2007). By and large, the two leaders have made many decisions that deal with security, economics, and business aspects of the relationship, making it in the top of its fame. (Gearan, 2008)

In early 2018, the Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman visited the United States where he met with many top politicians, business people and Hollywood stars, including President Donald Trump, Bill and Hillary Clinton, Henry Kissinger, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and George W. Bush.[146][147]

2017 US–Saudi Arms Deal

US President Donald Trump authorized a nearly $110B arms deal with Saudi Arabia, worth $300B over a ten-year period, signed on the 20 May 2017, this includes training and close co-operation with the Saudi Arabian military.[148] Signed documents included letters of interest and letters of intent and no actual contracts.[149]

US defense stocks reached all-time highs after Donald J. Trump announced a $110 billion arms deal to Saudi Arabia.[150][151][152]

Saudi Arabia signed billions of dollars of deals with U.S. companies in the arms industry and petroleum industry, including Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, General Dynamics, Northrop Grumman, General Electric, Exxon Mobil, Halliburton, Honeywell, McDermott International, Jacobs Engineering Group, National Oilwell Varco, Nabors Industries, Weatherford International, Schlumberger and Dow Chemical.[153][154][155][156][157][158]

In August, 2018, a laser-guided Mark 82 bomb sold by the U.S. and built by Lockheed Martin was used in the Saudi-led coalition airstrike on a school bus in Yemen, which killed 51 people, including 40 children.[159]

On May 27, 2020, Bob Menendez, a Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee claimed during a CNN op-ed that the Trump administration had been covertly working on plans of initiating a new sale of weapons contract worth $1.8 billion to Saudi Arabia.[1][160] According to the U.S.-based Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) analysis, American weapons in Yemen have killed at least 100,000 civilians, and over 10,000 people have died as a result of preventable diseases and epidemics like cholera and dengue fever, most of them children.[161]

See also

References

- Henderson, Simon. "The Long Divorce; How the U.S.-Saudi relationship grew cold under Barack Obama's watch". April 19, 2016. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- Keating, Joshua (6 November 2017). "The Fight for Survival Behind Saudi Arabia's Purge". Retrieved 1 February 2018 – via Slate.

- Gardner, Frank (20 April 2016). "How strained are US-Saudi relations?". BBC News.

- "The bizarre alliance between the US and Saudi Arabia is finally fraying". www.newstatesman.com.

- "The U.S. Might Be Better Off Cutting Ties With Saudi Arabia". Time.

- Sokоlsky, Perry Cammack, Richard. "The New Normal in U.S.-Saudi Relations". The National Interest.

- "Shifting Sands in the U.S.-Saudi Arabian Relationship | Middle East Policy Council". www.mepc.org.

- BBC World Service Poll Archived 2007-01-18 at the Wayback Machine GlobeScan

- Stokes, Bruce. "Which countries Americans like … and don't". December 30, 2013. pewresearch.org. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- Cordesman, Anthony H. (December 31, 2002). Saudi Arabia Enters The 21st Century: IV. Opposition and Islamic Extremism Final Review (PDF). CSIS. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- TOP 25 PLACES OF ORIGIN OF INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Institute of International Education

- "Jamal Khashoggi: Who is missing Saudi Journalist?". BBC News. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Trump vows 'severe punishment' if journalist Jamal Khashoggi was killed by Saudis". CNN. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Saudi Arabia and U.S. Clash Over Khashoggi Case". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Saudi Arabian King calls Turkish President over journalist Khashoggi's disappearance". CNN. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Surveillance footage shows Saudi 'body double' in Khashoggi's clothes after he was killed, Turkish source says". CNN. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Khashoggi murder: Crown prince vows to punish 'culprits'". BBC News. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "Middle East expert says there's 'unprecedented disruption' in US-Saudi relationship". The Hill. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Trump rebuilds relations with Saudi Arabia by nominating top general as envoy". Washington Examiner. 2018-11-15. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- Genin, Aaron (2019-04-01). "A GLOBAL, SAUDI SOFT POWER OFFENSIVE: A SAUDI PRINCESS AND DOLLAR DIPLOMACY". The California Review. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- "Menendez and Graham announce resolution on Saudi Arabia in wake of Khashoggi killing". Fox News. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "U.S. bans 16 Saudi individuals from U.S. for role in Khashoggi's murder". NBC News. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- "Pompeo Bars 16 Saudis From U.S. in Response to Khashoggi Killing". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Division, US Census Bureau Foreign Trade. "Foreign Trade: Data". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- Grayson, Benson Lee (1982). Saudi-American relations. University Press of America.

- "Chronology". PBS. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Chughtai, Alia (May 18, 2017). "US-Saudi Relations: A Timeline". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- Alhajji, Anas. "The Oil Weapon: Past, Present, and Future". Oil & Gas Journal. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- I. Andrew (28 February 1998). "Ambassador Parker T. Hart (1910-1997)". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. XI (5). Retrieved 20 January 2014. – via Questia (subscription required)

- Pollack, Josh (September 2002). "SAUDI ARABIA AND THE UNITED STATES, 1931-2002" (PDF). Middle East Review of International Affairs. 6 (2). Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. (1992). Saudi Arabia: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress.

- Metz, Helen Chapin (1993). Saudi Arabia : a country study. Library of Congress. Federal Research Division.

- Hart, Parker T. (1998). Saudi Arabia and the United States: Birth of a Security Partnership. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253334608. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

saudi arabia and the united states by parker t hart 1998.

- F. Gregory Gause, III (2010). The International Relations of the Persian Gulf. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0521190237. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- F. Gregory Gause, III (2010). The International Relations of the Persian Gulf. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0521190237. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- http://www-personal.umich.edu/~twod/oil-ns/articles/research-07/research-saudi/pollack.pdf

- F. Gregory Gause, III (2010). The International Relations of the Persian Gulf. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0521190237. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- F. Gregory Gause, III (2010). The International Relations of the Persian Gulf. Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0521190237. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Coll, Steve (2004). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from ... Penguin. ISBN 9781594200076. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Ottaway, David B.; Kaiser, Robert G. (Feb 13, 2002). "Marriage of Convenience: The U.S.-Saudi Alliance". Washington Post.

- Times, Michael R. Gordon and Special To the New York. "BUSH SENDS U.S. FORCE TO SAUDI ARABIA AS KINGDOM AGREES TO CONFRONT IRAQ; Bush's Aim's: Deter Attack, Send a Signal". Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- "Bush orders Operation Desert Shield". HISTORY. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- Rashid, Nasser Ibrahim (1992). Saudi Arabia and the Gulf War. Intl Inst of Technology Inc.

- "US pulls out of Saudi Arabia". BBC News. April 29, 2003. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- Plotz, David (2001) What Does Osama Bin Laden Want?, Slate

- "Arms for the King and His Family: The U.S. Arms Sale to Saudi Arabia". Jerusalem Center For Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "US-Saudi Security Cooperation, Impact of Arms Sales – Cordesman". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- The King's Messenger: Prince Bandar bin Sultan and America's Tangled ... By David B Ottaway

- House, Karen Elliott (2012). On Saudi Arabia : Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines and Future. Knopf. p. 238.

- Said, Summer; Benoit Faucon (July 29, 2013). "Shale Threatens Saudi Economy, Warns Prince Alwaleed". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "Saudi to reassess relations with US: report". Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Worth, Robert F. (October 18, 2013). "Saudi Arabia Rejects U.N. Security Council Seat in Protest Move". New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- Balluck, Kyle (November 28, 2013). "Obama, Saudi king to 'consult regularly' on Iran". The Hill. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- Schulmeister, Stephan (March 2000). "Globalization without Global Money: The Double Role of the Dollar as National Currency and World Currency". Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 22 (3): 365–395. doi:10.1080/01603477.2000.11490246. ISSN 0160-3477.

- Clark, William R. Petrodollar Warfare: Oil, Iraq and the Future of the Dollar, New Society Publishers, 2005, Canada, ISBN 0-86571-514-9

- "Petrodollar power". The Economist. 7 December 2006.

- CARTER, SHAN (September 8, 2011). "One 9/11 Tally: $3.3 Trillion". New York Times. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Friedman, Thomas (June 2, 2002). "War of Ideas". New York Times. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

The idea people who inspired the hijackers are religious leaders, pseudo-intellectuals, pundits, and educators, primarily in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, which continues to use its vast oil wealth to spread its austere and intolerant brand of Islam, Wahhabism.

- Bradley, John R. (2005). Saudi Arabia Exposed. Macmillan. p. 6.

- Michael R. Dillon (September 2009). "Wahhabism: Is it a Factor in the Spread of Global Terrorism?" (PDF). NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2014.

The events that transpired on September 11, 2001, shook the foundation of the U.S.-Saudi relationship by raising serious concerns and questions regarding the role of the Saudi government and their Wahhabi ideology played in terrorism associated with Al-Qaeda. The attacks shined a light on Saudi Arabia since 15 out of 19 hijackers as well as Osama bin Laden and many of the global "jihadists" that participated in the conflicts fought in Bosnia, Chechnya, Afghanistan, and Iraq were Saudi nationals. This naturally led the U.S. government and its people to ask serious questions as to what is wrong with Saudi Arabia and to draw conclusions about its religious ideology and institutions.

- Chair: Maurice R. Greenberg. "Task Force Report Terrorist Financing". October 2002. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Rodenbeck, Max (October 21, 2004). "Unloved in Arabia (book reviews)". The New York Review of Books. 51 (16).

Judging by the tenor of much that has been said about Saudi Arabia since September 11, quite a few people seem to think something similar should be done with the present-day Saudis. In Congress, on American television, and in print, their country has been portrayed as a sort of oily heart of darkness, the wellspring of a bleak, hostile value system that is the very antithesis of our own. America's seventy-year alliance with the kingdom has been reappraised as a ghastly mistake, a selling of the soul, a gas-addicted dalliance with death.

- Lacey, Robert (2009). Inside the Kingdom : Kings, Clerics, Modernists, Terrorists, and the Struggle for Saudi Arabia. Viking. pp. 288–9.

"In July that year [2002?] Laurent Murawiec, a French analyst with the RAND Corporation, had given a 24-slide presentation to the prestigious Defense Policy Board, an arm of the Pentagon, suggesting that the United States should consider 'taking [the ]Saudi out of Arabia' by forcibly seizing control of the oil fields, giving the Hijaz back to the Hashemites, and delegating control of the holy cities to a multinational committee of moderate, non-Wahhabi Muslims: the House of Saud should be sent home to Riyadh. 'Saudi Arabia supports our enemies and attacks our allies,' argued Murawiec, a protege of Richard Perle's, the neocon advocate of war with Iraq who chaired the Policy Board. 'The Saudis are active at every level of the terror chain, from planners to financiers, from cadre to foot soldier, from ideologist to cheerleaders.' They were 'the kernel of evil, the prime mover, the most dangerous opponent' in the Middle East.

- Bradley, John R. (2005). Saudi Arabia Exposed : Inside a Kingdom in Crisis. Palgrave. p. 169.

In the climate of intense anti-American sentiment in Saudi Arabia after September 11, it is certainly true that any association with U.S.-inspired `reform` ... is fast becoming a hindrance rather than a help.

- Bradley, John R. (2005). Saudi Arabia Exposed : Inside a Kingdom in Crisis. Palgrave. p. 211.

Anti-U.S. sentiment inside Saudi Arabia is now at an all-time high, following the outrages at the Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad and Washington's continued support for Israel's often brutal suppression of the Palestinians.

- SCIOLINO, ELAINE (January 27, 2002). "Don't Weaken Arafat, Saudi Warns Bush". New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

A classified American intelligence report taken from a Saudi intelligence survey in mid-October [2001] of educated Saudis between the ages of 25 and 41 concluded that 95 percent of them supported Mr. bin Laden's cause, according to a senior administration official with access to intelligence reports.

- "Saudi Arabians Overwhelmingly Reject Bin Laden, Al Qaeda, Saudi Fighters in Iraq, and Terrorism; Also among most pro-American in Muslim world. Results of a New [2006] Nationwide Public Opinion Survey of Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Terror Free Tomorrow. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Bradley, John R. (2005). Saudi Arabia Exposed : Inside a Kingdom in Crisis. Palgrave. p. 85.

In a region obsessed with conspiracy theories, many Saudis, both Sunni and Shiite, think that Washington has plans to split off the Eastern Province into a separate entity and seize control of its oil reserves after Iraq has stabilized.

- "Frontline Saudi Arabia". PBS.org. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Rich, Frank (December 7, 2002). "Pearl Harbor Day, 2002". New York Times. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

... spokesman for our ally Saudi Arabia who on Tuesday declared that his country was the victim of unwarranted American intolerance bordering on hate. ... the Saudi minister of the interior, Prince Nayef, maintained as recently as last week that the 15 Saudi hijackers of 9/11 were dupes in a Zionist plot.

- Kaim, Markus (2008). Great powers and regional orders: the United States and the Persian Gulf. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7546-7197-8.

- Al-Rasheed, Madawi (2010). A History of Saudi Arabia. pp. 178, 222. ISBN 978-0-521-74754-7.

- "Saudi Arabia must face U.S. lawsuits over Sept. 11 attacks" Archived November 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Reuters. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- Maier, Timothy (2002-06-24). "Kids Held Hostage in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Insight. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- Maier, Timothy (2001-11-27). "Stolen Kids become Pawns in Terror War" (PDF). Insight. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- Maier, Timothy (2001-06-18). "All Talk, No Action on Stolen Children" (PDF). Insight. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- Maier, Timothy (2000-10-07). "A Double Standard for Our Children" (PDF). Insight. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- Spillius, Alex (5 December 2010). "Wikileaks: Saudis 'chief funders of al-Qaeda'". Telegraph. London. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- 'Fueling Terror', Institute for the Analysis of Global Terror, http://www.iags.org/fuelingterror.html

- "Why Obama doesn't want 9/11 families suing Saudi Arabia". USA Today. September 23, 2016.

- "Saudi Arabia threatens to pull $750B from U.S. economy if Congress allows them to be sued for 9/11 terror attacks". New York Daily News. April 16, 2016.

- "Mayor de Blasio joins Democrats in calling on President Obama to go after Saudi Arabia on 9/11 ties". New York Daily News. April 19, 2016.

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-saudi-sept11/saudi-arabia-must-face-u-s-lawsuits-over-sept-11-attacks-idUSKBN1H43A1

- Norton, Ben (28 June 2016). "CIA and Saudi weapons for Syrian rebels fueled black market arms trafficking, report says". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016.

- "Gulf allies and 'Army of Conquest". Al-Ahram Weekly. 28 May 2015.

- "Saudi Arabia just replenished Syrian rebels with one of the most effective weapons against the Assad regime Archived 3 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Business Insider. 10 October 2015.

- "Syrian sniper: US TOW missiles transform CIA-backed Syria rebels into ace marksmen in the fight against Assad Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine". International Business Times. 30 October 2015.

- "ISIS used US-made anti-tank missiles near Palmyra Archived 3 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine". Business Insider. 9 June 2015.

- Acceptable Losses: Aiding and abetting the Saudi slaughter in Yemen

- Liautaud, Alexa (June 13, 2017). "The Senate-approved Saudi Arms deal is a disaster for Yemen". Vice News. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Cooper, Helene (13 June 2017). "Senate Narrowly Backs Trump Weapons Sale to Saudi Arabia". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Carney, Jordain (13 June 2017). "Senate rejects effort to block Saudi arms sale". The Hill. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- "Gabbard condemns arms sale to Saudi Arabia | Asian American Press". aapress.com. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- Beavers, Olivia (2017-05-20). "Dem senator: Trump's arms deal with Saudis a 'terrible idea'". TheHill. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- Hensch, Mark (2017-05-23). "Paul plans to force vote on $110B Saudi defense deal". TheHill. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- "Senators Target Trump's Proposed $110B Weapons Deal With Saudi Arabia". 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-06-19.

- Hensch, Mark (2017-05-24). "Paul: $110B Saudi arms deal 'a travesty'". TheHill. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- "Congress Votes to Say It Hasn't Authorized War in Yemen, Yet War in Yemen Goes On". The Intercept. 14 November 2017.

- "Jamal Khashoggi: Britain challenges Saudi Arabia". BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Jamal Khashoggi: Trump 'demands answers' on missing Saudi". BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Jamal Khashoggi disappearance: 'Hell to pay' for Saudi Arabia if journalist was murdered, Lindsey Graham says". The Independent. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "US condemns Saudi Arabia over religious freedom abuses". CNN. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- "House rejects Saudi weapons sales; Trump to veto". Reuters. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "House votes to block Trump's arms sales to Saudi Arabia, setting up a likely veto". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019". ACLED.

- "Trump Jr. and Other Aides Met With Gulf Emissary Offering Help to Win Election". The New York Times. 19 May 2018.

- "Trump Jr. met Gulf princes' emissary in 2016 who offered campaign help". Reuters. 19 May 2018.

- Keating, Joshua (March 8, 2018). "It's Not Just a "Russia" Investigation Anymore". Slate.

- "Report: Saudis, UAE funnelled millions to Trump 2016 campaign". Al-Jazeera. February 25, 2020.

- "Pensacola naval base shooting that left 3 dead presumed to be terrorism, FBI says". NBCNews. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- "Pentagon suspends military training of Saudi students after Pensacola shooting". The Guardian. December 10, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- Rambaran, Vandana (December 6, 2019). "6 Saudi nationals detained for questioning after NAS Pensacola shooting: official". Fox News. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- Kurlantzick, Joshua (2007-05-07). "Putting Lipstick on a Dictator". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- Lichtblau, Eric (March 1, 2011). "Arab Uprisings Put U.S. Lobbyists in Uneasy Spot". The New York Times.

- Bradley, John R. (2005). Saudi Arabia Exposed : Inside a Kingdom in Crisis. Palgrave. p. 213.

The ruling Al-Saud family has long sought ... to be the ally of the West, especially of the United States, while both influencing it and keeping its corrupting influences at bay, and simultaneously backing a Wahhabi establishment it relies on to remain in power but which also ultimately seeks the West's destruction...

- Bradley, John. "Waiting in the shadows" (3–9 June 2004). AL-AHRAM. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Bradley, John R. (2005). Saudi Arabia Exposed : Inside a Kingdom in Crisis. Palgrave. pp. 210–11.

[the Gulf War was] aimed only at gaining control of Iraq's natural resources. While that argument could be made quite strongly by anyone else, it is a bit rich coming from any member of the Al-Saud family. During the Iraq war, Saudi Arabia secretly helped the United States by allowing operations from at least three air bases, permitting special forces to stage attacks from Saudi soil, and providing cheap fuel. The American air campaign against Iraq was essentially managed from inside Saudi borders, where military officers operated a command center and launched refueling tankers, F-16 fighter jets, and sophisticated intelligence-gathering flights.

- "Saudi-US Economic Relations 3 Riyadh". May 16, 2017. Saudi Press Agency. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "How strained are US-Saudi relations?". BBC News. 20 April 2016.

- "Old friends US and Saudi Arabia feel the rift growing, seek new partners". Asia Times. 2 May 2016.

- "America Is Complicit in the Carnage in Yemen". The New York Times. 17. August 2016.

- "Rights group blasts U.S. "hypocrisy" in "vast flood of weapons" to Saudi Arabia, despite war crimes". Salon. 30. August 2016.

- "The NSA's New Partner in Spying: Saudi Arabia's Brutal State Police" Glenn Greenwald, The Intercept, July 25, 2014

- Los Angeles Times (22 January 2015). "King Abdullah, 90, of Saudi Arabia dies; Obama offers condolences for 'candid' leader - LA Times". latimes.com. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "U.S. carrier moving off the coast of Yemen to block Iranian arms shipments". USA Today. 20 April 2015.

- "Saudi Arabia launches air attacks in Yemen". The Washington Post. 25 March 2015.

- Warren P. Strobel, and Jonathan Landay (10 October 2016). "Exclusive: As Saudis bombed Yemen, U.S. worried about legal blowback". Reuters.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Weizmann, Nathalie (27 March 2015). "International Law on the Saudi-Led Military Operations in Yemen". Just Security.

- "U.S. and U.K. Continue to Actively Participate in Saudi War Crimes, Targeting of Yemeni Civilians". The Intercept. October 10, 2016.

- "Senators consider vote to block US arms deal to Saudi Arabia – report". The Guardian. 14 August 2016.

- "Senate rejects bill blocking U.S.-Saudi arms deal; rights groups applaud "growing dissent" on Yemen war crimes". Salon. 21 September 2016.

- "Readout of Secretary Mattis' Call with Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's Deputy Crown Prince and Minister of Defense Mohammed bin Salman". U.S. Department of Defense. January 31, 2017.

- "Pentagon Weighs More Support for Saudi-led War in Yemen". Foreign Policy. March 26, 2017.

- "America's Support for Saudi Arabia's War on Yemen Must End". The Nation. April 5, 2017.

- "Trump administration weighs deeper involvement in Yemen war". The Washington Post. March 26, 2017.

- Bethan McKernan, "CIA awards Saudi crown prince with medal for counter-terrorism work", The Independent, 10 February 2017

- "U.S. Total Crude Oil and Products Imports". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- "OEC - Saudi Arabia (SAU) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners". atlas.media.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- "Saudi Arabia | United States Trade Representative". ustr.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- Copp, Tara (2018-10-28). "If US, Saudi Arabia split over journalist's murder, will troops ever be able to leave Syria?". Military Times. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- "US court allows lawsuits claiming Saudi Arabia helped plan 9/11 terror attacks". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- "Feds launch investigation into disappearance of Saudi students facing U.S. charges". Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Feds investigate if Saudi government helped students evade justice". CNN. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Senate Passes Wyden Bill to Provide Answers About Saudi Fugitive. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "The King Abdullah Scholarship Program". Saudi Cultural Bureau in Canada. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman toured Hollywood, Harvard and Silicon Valley on US visit". The Independent. 7 April 2018.

- "MBS meets AIPAC, anti-BDS leaders during US visit". Al-Jazeera. 29 March 2018.

- David, Javier E. (20 May 2017). "US-Saudi Arabia ink historic 10-year weapons deal worth $350 billion as Trump begins visit". Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Riedel, Bruce (5 June 2017). "The $110 billion arms deal to Saudi Arabia is fake news". Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "U.S. defense stocks jump on Saudi arms deal". Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- Thomas, Lauren (2017-05-22). "Defense stocks soar to all-time highs on $110 billion US-Saudi Arabia weapons deal". CNBC. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- CNBC (2017-05-22). "After Saudi arms deal, defense shares fly". CNBC. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- "Factbox: Deals signed by U.S. companies in Saudi Arabia". Reuters. May 20, 2017.

- "Saudi Arabia Welcomes Trump With Billions of Dollars of Deals". Bloomberg. May 20, 2017.