South Africa–United States relations

The United States and South Africa currently maintain bilateral relations with one another. The United States and South Africa have been economically linked to one another since the late 18th century which has continued into the 21st century. U.S. and South Africa relations faced periods of strain throughout the 20th century due to the segregationist, white rule in South Africa, from 1948–1994. Following apartheid in South Africa, the U.S. and South Africa have developed a strategically, politically, and economically beneficial relationship with one another and currently enjoy "cordial relations"[1] despite "occasional strains".[1] South Africa remains the United State's largest trading partner in Africa as of 2019.[1]

| |

South Africa |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of South Africa, Washington, D.C. | Embassy of the United States, Pretoria |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador M. J. Mahlangu | Chargé d'affaires Jessye Lapenn |

History

The United States has maintained an official presence in South Africa since 1799, when an American consulate was opened in Cape Town. The U.S. Embassy is located in Pretoria, and Consulates General are in Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town. In 1929, the United States and South Africa established official diplomatic relations. However, following WWII, both the United States and South Africa had political affairs that impacted their relations with all of the world. The United States had entered into the Cold War with the Soviet Union; while, simultaneously, the Nationalist Party in South Africa won the 1948 election against its rival, the United Party. With the Nationalist Party in power, this meant that the segregationist policies that had been impacting South Africa had become lawful, and the Apartheid Era had begun. Due to this, the United States policies towards South Africa were altered; and, overall, the relationship between South Africa and the United States was strained until the end of apartheid rule. Following the Apartheid Era, the United States and South Africa have maintained bilateral relations.[2]

Apartheid Era

The Apartheid Era began under the rule of the Nationalist Party which was elected into power 1948.[3] Throughout the Apartheid Era, United States foreign policy was heavily influenced by the Cold War. During the early period of apartheid in South Africa, the United States maintained friendly relations with South Africa, which may be attributed to the anti-communist ideals held by the National Party.[4][5] However, over the course of the 20th century, American-South African relations were impacted by the apartheid system in place under the Nationalist Party. At times, the United States cooperated with and maintained bilateral relations with South Africa; and, at other times, the United States took political action against it.

Cooperation

Throughout the Apartheid Era, economic ties between the United States and South Africa played a prominent role in their relations with one another. From the 1950s to the 1980s, United States exports to, imports from, and direct investment in South Africa as a whole increased.[6] South Africa was seen as an important trade partner because it provided the United States with access to various mineral resources— like chromium, manganese, vanadium— vital for the U.S. steel industry.[7] Aside from trade and investment, South Africa also provided a strategic location for a naval base and access to much of the African continent.[8] In addition, the United States had a NASA missile tracking station located in South Africa, which became controversial in American politics due to segregation being practiced on the stations in compliance with apartheid policy.[9][10] In the early 1950s the South African Air Force supported the United States during the Korean War by fighting on the side of the United Nations.

Resistance

Following the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, the United States relations with South Africa began to undergo changes.[11] In 1963, under the Kennedy Administration, the United States voluntarily placed an arms embargo on South Africa in cooperation with the United Nations Security Council Resolution 181.[12] After President Kennedy's assassination and under the Johnson Administration, the United States policy towards South Africa was greatly impacted by the Civil Rights Movement taking place at home. In regards to the African struggles in Africa, President Johnson shared that:

- The foreign policy of the United States is rooted in its life at home. We will not permit human rights to be restricted in our own country. And we will not support policies abroad which are based on the rule of minorities or the discredited notion that men are unequal before the law. We will not live by a double standard—professing abroad what we do not practice at home, or venerating at home what we ignore abroad.[13]

The primary political action taken by the Johnson Administration was the implementation of National Security Action Memorandum 295 in 1963. This, in short, aimed to promote change in apartheid policy in South Africa whilst still maintaining economic relations.[14][15] Similarly, in 1968, the Johnson Administration created a National Policy Paper which discussed the U.S. political objectives of balancing a bilateral economic relationship with South Africa, while also promoting the end of apartheid in South Africa.[16]

Under the Nixon Administration and the Ford Administration, although controversial, most scholars agree that these administrations failed to combat apartheid policy in South Africa.[17] The Carter Administration is known for its confrontational strategy against apartheid and white rule in South Africa.[18] However, although the Carter Administration advocated for human rights in South Africa, most scholars agree that it was unsuccessful in creating change in South Africa. The Carter Administration feared that divestment of American companies in South Africa could have worsened the conditions for the black majority, while strengthening the position of the white minority in South Africa.[19] This resulted in the Carter Administration refraining from placing sanctions—often promoted by the anti-apartheid movement—on South Africa, and lead to growth in investments in South Africa.[20]

Throughout the Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations, the United States anti-apartheid movement as well as divestment from South Africa campaigns increasingly gained support from the American public. The growth of the anti-apartheid movement as well as the divestment campaign lead to increased pressure on the U.S. government to take action against apartheid policy in South Africa. It is during this time— when these movements had more support than ever before— that the Reagan Administration came into office.[21]

The Reagan administration practiced a policy of "constructive engagement" to gently push South Africa toward a moral racially sensitive regime. The policy had been developed by State Department official Chester Crocker as part of a larger policy of cooperation with South Africa to address regional turmoil.[22] However, anger was growing in the United States, with leaders in both parties calling for sanctions to punish South Africa. Lawrence Eagleburger, Reagan's Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, in June 1983 announced a clear shift in policy to an insistence upon fundamental change in Pretoria's racial policy, as the Reagan administration had to confront growing congressional and public support for sanctions.[23] The new policy was inadequate to such anti-apartheid leaders as Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Weeks after it was announced that he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize he went to the United States and denounced the Reagan administration's policy as inherently immoral. On 4 December 1984, he told the U.S. House Subcommittee on Africa:

- Apartheid is an evil as immoral and unchristian in my view as Nazism, and in my view the Reagan administration's support in collaboration with it is equally immoral, evil, and totally unchristian, without remainder.[24]

However, on 7 December, Tutu met face-to-face with Reagan at the White House. They agreed that apartheid was repugnant and should be dismantled by peaceful means.[25] Because efforts at constructive engagement had not succeeded in altering South Africa's policy of apartheid, Washington D.C. had to adapt this policy. In 1986, despite President Reagan's effort to veto it, the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 (CAAA) was enacted by United States Congress. This act was the first in this era that not only implemented economic sanctions, but also offered to aid to the victims living under apartheid rule.[26] The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act was the starting point for unified policy towards South Africa in United States politics. Under the Reagan, Clinton, and Bush administrations, there were continued efforts to try to end apartheid. By 1994, apartheid in South Africa had officially ended.[27] Nelson Mandela was elected as the first president of this newly democratic nation.

Post Apartheid

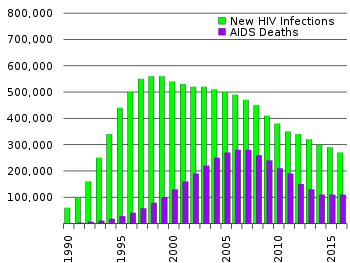

Since the abolition of apartheid and the first-ever democratic elections of April 1994, the United States has enjoyed a bilateral relationship with South Africa. Although there are differences of position between the two governments (regarding Iraq, for example), they have not impeded cooperation on a broad range of key issues. Bilateral cooperation in counter-terrorism, fighting HIV/AIDS, and military relations has been particularly positive. Through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the United States also provides assistance to South Africa to help them meet their developmental goals. Peace Corps volunteers began working in South Africa in 1997.

During the presidency of Thabo Mbeki (1999–2008) relations were strained due to a combination of the ANC's paranoia around alleged CIA activities in the country and perceived criticism of Mbeki's AIDS denialism, a feeling partly based on the ANC's experiences of tacit American support for the Apartheid government during the Reagan administration. The Bush administration's wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as well as its PEPFAR initiative (that clashed with Mbeki's views on AIDS) served to alienate the South African presidency until president Mbeki left government in 2008.[29]

Until 2008, the United States had officially considered Nelson Mandela a terrorist,[30] however on 5 July 2008 Mandela along with as other ANC members including the then current foreign minister were removed from a US terrorist watchlist. Harry Schwarz, who served as South African Ambassador to the United States during its transition to representative democracy (1991–1994), has been credited as having played one of the leading roles in the renewal of relations between the two nations.[31]

Peter Fabricius described Schwarz as having "engineered a state of US/South Africa relations better than it has ever been”.[32] The fact that Schwarz, for decades a well known anti-apartheid figurehead, was willing to accept the position was widely acknowledged as a highly symbolic demonstration of President F. W de Klerk's determination to introduce a new democratic system.[33][34][35][36] During Schwarz's tenure, he negotiated the lifting of US sanctions against South Africa, secured a $600 million aid package from President Bill Clinton, signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1991 and hosted President Mandela's state visit to the US in October 1994.[37]

On 28 January 2009, newly elected US President Barack Obama telephoned his newly installed counterpart Kgalema Motlanthe as one of a list of foreign contacts he had been working through since his presidential inauguration the previous week. Given primary treatment was South Africa's role in helping to resolve the political crisis in Zimbabwe. According to White House spokesman Robert Gibbs, the pair "shared concerns" on the matter. Obama credited South Africa for holding "a key role" in resolving the Zimbabwean crisis, and said that he was looking forward to working with President Motlanthe to address global financial issues at the 2009 G-20 London summit.[38]

The election of Obama along with Mbeki's departure from office as well as the enactment of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) with South Africa as a key beneficiary greatly improved opinions within the South African government of its relationship with the United States. As of 2014 the relationship between South Africa and the United States in the Zuma/Obama years is thought not to be as close as it was during the Mandela/Clinton years but greatly improved since the Mbeki/Bush years.[29] The Zuma years coincided with a continuation of cooling of South Africa–United States relations whilst China–South Africa relations warmed significantly[39] as South Africa focused diplomatic efforts on supporting the BRICS initiative.

During the Trump administration relations between the two countries cooled due to statements made by President Trump regarding land reform in South Africa and the listing of South Africa as one of ten countries the "worst record" of supporting US positions in the United Nations. The publication of the list was accompanied with the statement that the Trump administration was considering cutting off American aid to listed countries.[40]

Diplomatic visits

Diplomatic visits between the two nations increased near the end of apartheid. In February 1990, U.S. President George H.W. Bush invited both sitting South African President F.W. de Klerk and ANC leader Nelson Mandela to visit the White House. Both men accepted the invitation, with de Klerk scheduled to visit 18 June 1990 and Mandela, recently released from prison, scheduled to visit a week later. After controversy arose in South Africa, de Klerk postponed his visit. Mandela visited Washington on 24 June 1990 and met with President Bush and other officials. He also addressed a joint session of Congress. In September, de Klerk visited Washington, the first official state visit by a South African leader.

Mandela was subsequently elected President of South Africa, and U.S. Vice President Al Gore and First Lady Hillary Clinton attended his inauguration in Pretoria in May 1994. In October of that year, Mandela returned to Washington for a state dinner hosted by U.S. President Bill Clinton.

President Clinton visited South Africa in March 1998, marking the first time a sitting U.S. president visited the country. Since Clinton's visit, two of his successors have visited the country: President George W. Bush visited in July 2003, and President Barack Obama visited in June 2013.

Economic links

As of 2020 South Africa is the largest trade partner and investment source for the United States in Africa with over 600 American firms operating in the country. US$7.3 billion in direct investment from the United States to South Africa was recorded in 2017 while South African direct investment in the United States totaled US$4.1 billion for the same year. Thus making South Africa a net beneficiary of American investment.[41] Bilaterial trade between the two countries totaled US$18.9 billion with South Africa having a surplus of US$2.1 billion for 2018.[41][42] This partly attributed to the AGOA which gives South Africa key trading rights and reduced tariffs thereby allowing the country to diversify its exports when trading with the United States.[41]

The United States has used threats to remove South Africa from AGOA to lobby South Africa to allow for increase imports of American chicken and for the country not to pass certain legislation involving American companies.[41] Such as the Private Security Industry Regulation Amendment Bill which would have seen all foreign security companies in South Africa sell off 51% ownership to South African entities.[43]

Principal officials

Principal U.S. officials

- Ambassador – Lana Marks[44]

- Deputy Chief of Mission – Jessye Lapenn

- Commercial Counselor – Pamela Ward

- Economic Counselor – Alan Tousignant

- Political Counselor – Ian McCary

- Management Counselor – Russell LeClair

- Public Affairs Counselor – Craig Dicker

- Defense and Air Attache – Colonel Michael Muolo

- USAID Director – Carleene Dei

- Agricultural Attache – Jim Higgiston

- Health Attache – Stephen Smith

- Consul General Cape Town – Virginia Blaser

- Consul General Durban – Sherry Zalika Sykes

- Consul General Johannesburg – Michael McCarthy

Principal South African officials

- Ambassador – Mninwa Johannes Mahlangu

See also

- South African Americans

- Foreign relations of South Africa

- Foreign relations of the United States

- Constructive engagement

- Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986

- Free South Africa Movement

Notes

- Cook, Nicolas (30 September 2019). "South Africa: Current Issues, Economy,and U.S. Relations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "U.S. Relations With South Africa". U.S. Department of State. BUREAU OF AFRICAN AFFAIRS. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Beck, Rodger B. (2000). History of South Africa. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 124.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5.

- U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (31 January 1949). "The Political Situation in the Union of South Africa". FOIA Electronic Reading Room: 2.

- Alex Thomson (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 11.

- Thomson, p 8.

- U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (31 January 1949). "The Political Situation in the Union of South Africa". FOIA Electronic Reading Room: 2.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 76.

- Gillette, Robert., Robert (1973). "South Africa: NASA Inches Out of a Segregated Tracking Station.". Science. 181 (4097): 331–32, 380. Bibcode:1973Sci...181..331G. doi:10.1126/science.181.4097.331. PMID 17832025.

- Herbst, Jeffrey (2003). "Analyzing Apartheid: How Accurate Were US Intelligence Estimates of South Africa, 1948–94?". African Affairs. 102 (406): 81–107. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a138812.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 35.

- Anyaso, Claudia E. (2011). Fifty Years of U.S. Africa Policy: Reflections of Assistant Secretaries for African Affairs and U.S. Embassy Officials, 1958–2008. Arlington, VA: Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. p. 6.

- Irwin, Ryan M. (7 September 2012). Gordian Knot: Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order. Oxford University Press.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 50.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 61.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 63–68.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 89.

- Nicol, Davidson (1983). "United States Foreign Policy in Southern Africa: Third-World Perspectives". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 21 (4): 587–603. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00024228.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 102–4.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 106–123.

- J. E. Davies, Constructive Engagement? Chester Crocker and American Policy in South Africa, Namibia and Angola 1981–1988 (2008).

- Michael Clough, "Beyond constructive engagement." Foreign Policy;; 61 (1985): 3–24. Online

- John Allen (2008). Desmond Tutu: Rabble-Rouser for Peace: The Authorized Biography. Lawrence Hill Books. p. 248. ISBN 9781556527982.

- Allen, p 249.

- Clarizio, Lynda M. Bradley Clements and Erika Geetter (May 1989). "United States Policy toward South Africa". Human Rights Quarterly. 11 (2): 253.

- Thomson, Alex (2015). U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa, 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 174.

- Chin, Roger (2015). "PEPFAR Funding and Reduction in HIV Infection Rates in 12 Focus Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Quantitative Analysis". International Journal of MCH and AIDS.

- Pillay, Verashni (15 September 2014). "How the US and South Africa became friends again". Mail and Guardian. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- Hall, Mimi (1 May 2008). "U.S. has Mandela on terrorist list". USA Today. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "A job well done, Harry!". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Quoted in AFP 2009.

- Ol, Eric; er. "With Chinese and Russian Warships Heading to South Africa, Pretoria Sends a Powerful Message to the U.S." The China Africa Project. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Fabricius, Peter (25 September 2018). "US president's vow to drop countries that are 'not our friends' threatens US aid to SA | Daily Maverick". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Soko, Mills. "South Africa must get ready for an inevitable loosening of trade ties with the US". The Conversation. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "South Africa - Agoa.info - African Growth and Opportunity Act". agoa.info. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "South Africa expects challenge to security law, says Minister Davies - Agoa.info - African Growth and Opportunity Act". agoa.info. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-receives-letters-credence-ambassadors-and-high-commissioners

References

- Agence France-Presse. "Obama phones Motlanthe." News24, 29 January 2009.

Further reading

- Davies, J. E. Constructive Engagement? Chester Crocker and American Policy in South Africa, Namibia and Angola 1981–1988 (2008).

- Kline, Benjamin. The United States and South Africa during the Bush Administration: 1988-91" Journal of Asian & African Affairs (1993) 4#2 pp 68-83.

- Lulat, Y. G-M. United States Relations with South Africa: A Critical Overview from the Colonial Period to the Present (2008).

- Massie, Robert. Loosing the Bonds: The United States and South Africa in the Apartheid Years (1997).

- Mitchell, Nancy. Jimmy Carter in Africa: Race and the Cold War (Stanford UP, 2016), 913pp. excerpt

- Samson, Olugbenga. "America’s Inconsistent Foreign Policy to Africa; a Case Study of Apartheid South Africa." (MA thesis, East Tennessee State University, 2018) online.

- Schraeder, Peter J. United States Foreign Policy Toward Africa: Incrementalism, Crisis, and Change. (1994).

- Thomson, Alex. U.S. Foreign Policy Towards Apartheid South Africa 1948–1994: Conflict of Interests (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Historiography

- Lulat, Y. G-M. , ed. U.S. Relations with South Africa: Books, documents, reports, and monographs (1991), Westview Press, Boulder, CO. ISBN 978-0-8133-7138-2.