"Polish death camp" controversy

"Polish death camp" and "Polish concentration camp" are misnomers[1][2] that have been a subject of controversy and legislation. Such terms have been used by news media and by public figures in reference to concentration camps that were built and run during World War II by Nazi Germany in German-occupied Poland.

When used in relation to the Holocaust or to the murder of Poles and other nationalities in German-operated facilities, these phrases refer to the camps' geographic location in German-occupied Poland. However, the expressions have also been seen as undermining Germany's responsibility for the Holocaust, and can be misconstrued as meaning "death camps set up by Poles" or "run by Poland".[3] Polish officials and organizations have objected to such terms as misleading.

In 2018 an Amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance was signed into law by Polish President Andrzej Duda. It criminalized false public statements that ascribe to the Polish nation collective responsibility in Holocaust-related crimes, crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, or war crimes, or which "grossly reduce the responsibility of the actual perpetrators". Exempted from such strictures were scholarly studies, discussions of history, and artistic activities.[4] It was generally understood that the law would have criminalized the use of the expressions "Polish death camp" and "Polish concentration camp".[5][6][7] The legislation was controversial; it led to Israeli-Polish consensus-building, cooperation in rewriting the legislation four months later, and a joint statement condemning both antisemitism and anti-Polish sentiment.[8]

Historical context

During World War II, three million Polish Jews (90% of the prewar Polish-Jewish population) were killed as a result of Nazi German genocidal action. At least 2.5 million non-Jewish Polish civilians and soldiers also perished.[9] One million non-Polish Jews were also forcibly transported by the Nazis and killed in German-occupied Poland.[10] At least 70,000 ethnic Poles who were not Jewish were murdered by Nazi Germany in the Auschwitz concentration camp alone.[11]

After the German invasion, Poland, in contrast to cases such as Vichy France, experienced direct German administration rather than an indigenous puppet government.[12][13]

The western part of prewar Poland was annexed outright by Germany.[14] Some Poles were expelled from the annexed lands to make room for German settlers.[15] Parts of eastern Poland became part of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine and Reichskommissariat Ostland. The rest of German-occupied Poland, dubbed by Germany the General Government, was administered by Germany as occupied territory. The General Government received no international recognition. It is estimated that the Germans killed more than 2 million non-Jewish Polish civilians. Nazi German planners called for "the complete destruction" of all Poles, and their fate, as well as that of many other Slavs, was outlined in a genocidal Generalplan Ost (General Plan East).[16]

Historians have generally stated that relatively few Poles collaborated with Nazi Germany, in comparison with the situations in other German-occupied countries.[12][13][17] The Polish Underground judicially condemned and executed collaborators,[18][19][20] and the Polish Government-in-Exile coordinated resistance to the German occupation, including help for Poland's Jews.[9]

Some Poles were complicit in, or indifferent to, the rounding up of Jews. There are reports of neighbors turning Jews over to the Germans or blackmailing them (see "szmalcownik"). In some cases, Poles themselves killed their Jewish fellow citizens, the most notorious examples being the 1941 Jedwabne pogrom and the 1946 Kielce pogrom, after the war had ended.[21][22][7]

.jpg)

However, many Poles risked their lives to hide and assist Jews. Poles were sometimes exposed by Jews they were helping, if the Jews were found by the Germans—resulting in the murder of entire Polish rescue networks.[23] The number of Jews hiding with Poles was around 450,000.[24] Possibly a million Poles aided Jews;[25] some estimates run as high as three million helpers.[26]

Poles have the world's highest count of individuals who have been recognized by Israel's Yad Vashem as Righteous among the Nations — non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews from extermination during the Holocaust.[27]

Occupied Poland was the only territory where the Germans decreed that any kind of help for Jews was punishable by death for the helper and the helper's entire family.[28] Of the estimated 3 million non-Jewish Poles killed in World War II, up to 50,000 were executed by Germany solely for saving Jews.[29]

Analysis of the expression

Supporting rationale

Defenders argue that the expression "Polish death camps" refers strictly to the geographical location of the Nazi death camps and does not indicate involvement by the Polish government in France or, later, in the United Kingdom.[30] Some international politicians and news agencies have apologized for using the term, notably Barack Obama in 2012.[31] CTV Television Network News President Robert Hurst defended CTV's usage (see § Mass media) as it "merely denoted geographic location", but the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council ruled against it, declaring CTV's use of the term to be unethical.[30] Others have not apologized, saying that it is a fact that Auschwitz, Treblinka, Majdanek, Chełmno, Bełżec, and Sobibór were situated in German-occupied Poland.

Commenting upon the 2018 bill criminalizing such expressions (see § 2018 Polish law), Israeli politician Yair Lapid justified the expression "Polish death camps" with the argument that "hundreds of thousands of Jews were murdered without ever meeting a German soldier".[32]

Criticism of the expression

Opponents of the use of these expressions argue that they are inaccurate, as they may suggest that the camps were a responsibility of the Poles, when in fact they were designed, constructed, and operated by the Germans and were used to exterminate both non-Jewish Poles and Polish Jews, as well as Jews transported to the camps by the Germans from across Europe.[33][34] Historian Geneviève Zubrzycki and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) have called the expression a misnomer.[1][2] It has also been described as "misleading" by The Washington Post editorial board,[35] The New York Times,[36] the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council,[30] and Nazi hunter Dr. Efraim Zuroff.[22] Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem described it as a "historical misrepresentation",[37] and White House spokesman Tommy Vietor referred to its use a "misstatement".[38]

Abraham Foxman of the ADL described the strict geographical defence of the terms as "sloppiness of language", and "dead wrong, highly unfair to Poland".[21] Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Adam Daniel Rotfeld said in 2005 that "Under the pretext that 'it's only a geographic reference', attempts are made to distort history".[39]

Public use of the expression

As early as 1944, the expression "Polish death camp" appeared as the title of a Collier's magazine article, "Polish Death Camp". This was an excerpt from the Polish resistance fighter Jan Karski's 1944 memoir, Courier from Poland: The Story of a Secret State (reprinted in 2010 as Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World). Karski himself, in both the book and the article, had used the expression "Jewish death camp", not "Polish death camp".[40][41] As shown in 2019, the Collier's editor changed the title of Karski's article typescript, "In the Belzec Death Camp", to "Polish Death Camp".[42][43]

Other early-postwar, 1945 uses of the expression "Polish death camp" occurred in the periodicals Contemporary Jewish Record,[44] The Jewish Veteran,[45] and The Palestine Yearbook and Israeli Annual,[46] as well as in a 1947 book, Beyond the Last Path, by Hungarian-born Jew and Belgian resistance fighter Eugene Weinstock[47] and in Polish writer Zofia Nałkowska's 1947 book, Medallions.[48]

A 2016 article by Matt Lebovic stated that West Germany's Agency 114, which during the Cold War recruited former Nazis to West Germany's intelligence service, worked to popularize the term "Polish death camps" in order to minimize German responsibility for, and implicate Poles in, the atrocities.[49]

Mass media

On 30 April 2004 a Canadian Television (CTV) Network News report referred to "the Polish camp in Treblinka". The Polish embassy in Canada lodged a complaint with CTV. Robert Hurst of CTV, however, argued that the term "Polish" was used throughout North America in a geographical sense, and declined to issue a correction.[50] The Polish Ambassador to Ottawa then complained to the National Specialty Services Panel of the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council. The Council rejected Hurst's argument, ruling that the word "'Polish'—similarly to such adjectives as 'English', 'French' and 'German'—had connotations that clearly extended beyond geographic context. Its use with reference to Nazi extermination camps was misleading and improper."[30]

In 2009 Zbigniew Osewski, grandson of a Stutthof concentration camp prisoner, announced that he was suing Axel Springer AG for calling Majdanek concentration camp a "former Polish concentration camp" in a November 2008 article in the German newspaper Die Welt.[51] The case started in 2012.[52]

On 23 December 2009, British historian Timothy Garton Ash wrote in The Guardian: "Watching a German television news report on the trial of John Demjanjuk a few weeks ago, I was amazed to hear the announcer describe him as a guard in 'the Polish extermination camp Sobibor'. What times are these, when one of the main German TV channels thinks it can describe Nazi camps as 'Polish'? In my experience, the automatic equation of Poland with Catholicism, nationalism and antisemitism – and thence a slide to guilt by association with the Holocaust – is still widespread. This collective stereotyping does no justice to the historical record."[53]

In 2010 the Polish-American Kosciuszko Foundation launched a petition demanding that four major U.S. news organizations endorse use of the expression "German concentration camps in Nazi-occupied Poland".[54][55]

Canada's Globe and Mail reported on 23 September 2011 about "Polish concentration camps". Canadian Member of Parliament Ted Opitz and Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Jason Kenney supported Polish protests.[56]

In 2013 Karol Tendera, who had been a prisoner at Auschwitz-Birkenau and is secretary of an association of former prisoners of German concentration camps, sued the German television network ZDF, demanding a formal apology and 50,000 zlotys, to be donated to charitable causes, for ZDF's use of the expression "Polish concentration camps".[57] ZDF was ordered by the court to make a public apology.[58] Some Poles felt the apology to be inadequate and protested with a truck bearing a banner that read "Death camps were Nazi German - ZDF apologize!" They planned to take their protest against the expression "Polish concentration camps" 1,600 kilometers across Europe, from Wrocław in Poland to Cambridge, England, via Belgium and Germany, with a stop in front of ZDF headquarters in Mainz.[59]

The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage recommends against using the expression,[60][61] as does the AP Stylebook,[62] and that of The Washington Post.[35] However, the 2018 Polish bill has been condemned by the editorial boards of The Washington Post[35] and The New York Times.[36]

Politicians

In May 2012 U.S. President Barack Obama referred to a "Polish death camp" while posthumously awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Jan Karski. After complaints from Poles, including Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski and Alex Storozynski, President of the Kosciuszko Foundation, an Obama administration spokesperson said the President had misspoken when "referring to Nazi death camps in German-occupied Poland."[63][64] On 31 May 2012 President Obama wrote a letter[65] to Polish President Komorowski in which he explained that he used this phrase inadvertently in reference to "a Nazi death camp in German-occupied Poland" and further stated: "I regret the error and agree that this moment is an opportunity to ensure that this and future generations know the truth."

Polish government action

Media

The Polish government and Polish diaspora organizations have denounced the use of such expressions that include the words "Poland" or "Polish". The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs monitors the use of such expressions and seeks corrections and apologies if they are used.[66] In 2005, Poland's Jewish[67] Foreign Minister Adam Daniel Rotfeld remarked upon instances of "bad will, saying that under the pretext that 'it's only a geographic reference', attempts are made to distort history and conceal the truth."[39][68] He has stated that use of the adjective "Polish" in reference to concentration camps or ghettos, or to the Holocaust, can suggest that Poles perpetrated or participated in German atrocities, and emphasised that Poland was the victim of the Nazis' crimes.[39][68]

Monuments

In 2008, the chairman of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (the IPN) wrote to local administrations, calling for the addition of the word "German" before "Nazi" to all monuments and tablets commemorating Germany's victims, stating that "Nazis" is not always understood to relate specifically to Germans. Several scenes of atrocities conducted by Germany were duly updated with commemorative plaques clearly indicating the nationality of the perpetrators. The IPN also requested better documentation and commemoration of crimes that had been perpetrated by the Soviet Union.[69]

The Polish government also asked UNESCO to officially change the name "Auschwitz Concentration Camp" to "Former Nazi German Concentration Camp Auschwitz-Birkenau", to clarify that the camp had been built and operated by Nazi Germany.[70][71][72][73] At its 28 June 2007 meeting in Christchurch, New Zealand, UNESCO's World Heritage Committee changed the camp's name to "Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940–1945)."[74][75] Previously some German media, including Der Spiegel, had called the camp "Polish".[76][77]

2018 Polish law and Israel-Polish consensus

On 6 February 2018 Poland's President Andrzej Duda signed into law an amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance, criminalizing statements that ascribe collective responsibility in Holocaust-related crimes to the Polish nation,[4] It was generally understood that the law would criminalize use of the expressions "Polish death camp" and "Polish concentration camp".[5][6][7] Israeli officials and Jewish organizations criticized the legislation as an attempt to restrict discussion of anti-semitism in Poland and of the culpability of some Poles in the Holocaust.[78][79][80] Israel and Poland worked together on a re-phrasing of the law, and in a joint statement condemning both antisemitism and anti-Polish sentiment.[8]

The original 1998 Act had already specifically criminalized "public denial, against the facts, of Nazi crimes, communist crimes, and other offenses constituting crimes against peace, crimes against humanity or war crimes, committed against persons of Polish nationality or against Polish citizens of other nationalities, between 1 September 1939 and 31 July 1990"—such denial being punishable by fine or imprisonment for up to 3 years.[81]

Polish reactions

The 2018 Polish law, and what many Poles have considered an international over-reaction to it, have engendered strong feelings in Poland.

In January 2018, Israeli and Jewish comments about the Amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance bill led, in Poland, to a spate of anti-Israel and antisemitic ripostes. State TV ran antisemitic crawls on a talk show; state-radio commentator Piotr Nisztor suggested that Poles who supported the official Israeli position might consider relinquishing their Polish citizenships; and TVP2 director Marcin Wolski remarked that the Auschwitz death camp might be called a "Jewish death camp", as Jewish Sonderkommando inmates had run its crematoria.[82][83][84]

On 29 January 2018 Polish President Andrzej Duda responded to official Israeli objections to the Polish bill, saying that Poland had been a victim of Nazi Germany and had not taken part in the Holocaust.[85] "I can never accept the slandering and libeling of us Poles as a nation or of Poland as a country through the distortion of historical truth and through false accusations." On 31 January 2018, before the Polish Senate vote on the bill, Deputy Prime Minister Beata Szydło said: "We Poles were victims, as were the Jews ... It is a duty of every Pole to defend the good name of Poland."[86]

On 8 February 2018 the Polish government opened a media campaign, in support of the Amendment, targeted to Poland, Israel, and the United States. Hashtags such as "#GermanDeathCamps" and "#PolishRighteousness" were spread by Polish government accounts, and a government-sponsored video went viral on Google, Facebook, and Twitter.[87][88][89]

On 14 March 2018 the Polish Bishops' Conference noted a rise in anti-Semitism stimulated by the controversy over the Amendment and declared anti-Semitism to be "contrary to the Christian tenet of loving one's neighbor."[90]

Israeli reactions

Some Israelis accused the Polish government of engaging in Holocaust denial. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu responded to the legislation, saying:[78] "One cannot change history, and the Holocaust cannot be denied."

Knesset member and former journalist Yair Lapid has claimed that "[t]here were Polish death camps".[91] Other Israeli officials such as Education and Diaspora Affairs Minister Naftali Bennett have termed the expression a "misrepresentation", although Bennett said of the proposed law "This is a shameful disregard of the truth. It is a historic fact that many Poles aided in the murder of Jews, handed them in, abused them, and even killed Jews during and after the Holocaust."[92]

After Poland's legislature began steps to outlaw use of the expression "Polish death camps", some Israeli officials expressed concern that Poland might try to whitewash its wartime history. "Those who see themselves as defenders of Poland's good name are often quick to point out that in Poland there was no Quisling regime comparable to that which existed in other countries occupied by Germany – and that the Polish underground fought the Germans tooth and nail," the director of the Israel Council on Foreign Relations, Laurence Weinbaum, wrote in The Washington Post in 2015. "The truth is that local authorities were often left intact in occupied Poland, and many officials exploited their power in ways that proved fatal to their Jewish constituents."[93][94]

However, Weinbaum was also highly critical of what he termed "the wild assertions of some of the Israelis who have weighed in with sweeping charges of Polish culpability for the Holocaust, and erroneous, disparaging declarations about the provenance of Auschwitz."[95] In a 1998 article he wrote that "Part of the hostility to Poland [in Jewish circles] is based on the entirely false impression that Germany chose occupied Poland as the venue for their death camps because they could count on Polish cooperation in carrying out the Final Solution. Although there is no historical evidence to support that contention, it has gained wide currency and credence ... Careless reference to 'Polish extermination camps', rather than German or Nazi camps, has also played a part in fostering this perception."[96]

Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, Yad Vashem, has opined: "There is no doubt that the term 'Polish death camps' is a historical misrepresentation [ ...] However, restrictions on statements by scholars and others regarding the Polish people's direct or indirect complicity with the crimes committed on their land during the Holocaust are a serious distortion."[37][97]

On 29 January 2018, Israeli Foreign Ministry Spokesman Emmanuel Nahshon tweeted, "Of course they were not Polish. Those were German death camps. The issue is the legitimate and essential freedom to talk about the involvement of Poles in the murder of Jews without fear or threat of penalisation. Simple."[98]

Israeli political scientist Shlomo Avineri said young Israelis unintentionally associate the Holocaust with Poland, sometimes far more than with Nazi Germany. Writing in Haaretz, he called for a reappraisal of Israeli Holocaust education policy, to more greatly emphasize German culpability and Polish resistance during the March of the Living.[99]

Israeli president Reuven Rivlin said in Auschwitz that historians should be able to study the Holocaust without restrictions. He also stated "There is no doubt that many Poles fought against the Nazi regime, but we cannot deny the fact that Poland and Poles lent a hand to the annihilation".[100]

In protest at what she saw as the censorship and "borderline Holocaust denial" provided by the 2018 bill, Israeli journalist Lahav Harkov repeatedly tweeted the phrase "Polish death camps".[101][102][83]

On 2 February 2019 the prime minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu said in Warsaw at the international conference on security issues in the Middle East that "Poles collaborated with the Nazis". Prime Minister of Poland Mateusz Morawiecki's office released a statement calling Netanyahu’s comments "surprising". Morawiecki also tweeted that there was "no Polish regime" during the Nazi occupation, emphasizing that both Jews and Poles suffered under German rule.[103]

Polish-American reactions

The 2018 law is supported by the president of the Polish American Congress.[104] It is opposed as counterproductive by the former president of the Kosciuszko Foundation, who launched a successful campaign to remove the expression "Polish death camps" from U.S. news publications.[105]

Jacek K. Matysiak, writing in the Polish-American newspaper Gwiazda Polarna, blames the current controversy on Benjamin Netanyahu's internal political struggles in Israel, and also sees it as related to Jewish claims against Poland for property lost by Polish Jews during World War II.[106]

Polish-Jewish reactions

In 2018 the Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Poland said the legislation has led to a "growing wave of intolerance, xenophobia, and anti-Semitism", making many community members fearful for their safety.[107][108]

In 1998, on the 50th anniversary of the founding of Israel, the Jewish-Polish historian Janusz Sujecki received from the Israeli ambassador to Poland, Yigal Antebi (diplomat), a prize recognizing Sujecki's "contributions to the preservation of Jewish culture in Poland". Twenty years later, in 2018, Sujecki returned the prize to the current Israeli ambassador to Poland, Anna Azari, in a "symbolic protest" against recent waves of "slander and libel" against Poland. Sujecki pointed out that, during the Holocaust, Poland had done all in her power to try to get the western Allies to stop the German mass murders of Jews, Poles, and other nationalities in German-occupied Poland. Jan Karski's report at a 1943 personal meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt brought no action, and Karski's personal report to Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise and other American and Jewish leaders brought only incredulity or indifference. Nor did Poland's western Allies react to appeals from the Polish government-in-exile in London, in 1944, to bomb the rail lines leading to the German concentration camps in occupied Poland.[109]

On 15 March 2018, a group of Polish rabbis thanked the Polish Bishops' conference for condemning a rise in anti-Semitism in the controversy, and said they would "continue to speak out against analogous attitudes among Jews."[90]

Other reactions

While the American Jewish Committee (AJC) has stated that it "has been for decades critical of such harmful terms as 'Polish concentration camps' and 'Polish death camps,' recognizing that these sites were erected and managed by Nazi Germany during its occupation of Poland", AJC has also said that, "while we remember the brave Poles who saved Jews, the role of some Poles in murdering Jews cannot be ignored", and that the AJC is "firmly opposed to legislation that would penalize claims that Poland or Polish citizens bear responsibility for any Holocaust crimes".[110][111]

According to Dr. Efraim Zuroff, use of the expression "Polish death camp" is misleading. He said "the Polish state was not complicit in the Holocaust, but many Poles were."[22][112]

On 3 February 2018 German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel tweeted: "I have been organizing youth travel to Auschwitz and Majdanek for 15 years as a group leader. That these camps were German - there can be no doubt! The use of the term "Polish death camp" is wrong."[113][114]

In February 2018 the Ruderman Family Foundation launched a campaign for the US government to sever its ties with Poland. The campaign included a YouTube video in which a group on-screen repeated the phrase "Polish Holocaust"; the video was removed after widespread criticism.[115][116]

Also in February 2018, an opinion piece by Anne Applebaum in The Washington Post emphasized the law's "stupidity and unenforceability", invoking the Streisand effect, but also argued that the Israeli government is using "this nasty little controversy for its own purposes."[117]

See also

- Anti-Polish sentiment

- Bogdan Musiał

- Collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II

- German-occupied Europe

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Institute of National Remembrance, Warsaw, Poland

- Laws against Holocaust denial—Poland

- Nazi crimes against the Polish nation

- Polenlager (German camps for Poles)

- Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust

- Roundup (history)

- Żegota

References

- Zubrzycki, Geneviève (2006). The Crosses of Auschwitz: Nationalism and Religion in Post-Communist Poland. University of Chicago Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-226-99305-8.

- Kampeas, Ron (30 May 2012). "White House 'regrets' reference to 'Polish death camp'". JTA.

- Gebert, Konstanty (2014). "Conflicting memories: Polish and Jewish perceptions of the Shoah" (PDF). In Fracapane, Karel; Haß, Matthias (eds.). Holocaust Education in a Global Context. Paris: UNESCO. p. 33. ISBN 978-92-3-100042-3.

- "Ustawa z dnia 26 stycznia 2018 r. o zmianie ustawy o Instytucie Pamięci Narodowej – Komisji Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, ustawy o grobach i cmentarzach wojennych, ustawy o muzeach oraz ustawy o odpowiedzialności podmiotów zbiorowych za czyny zabronione pod groźbą kary" [Act of 26 January 2018 amending the act on the Institute of National Remembrance - Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation, laws on graves and war cemeteries, laws on museums and the act on the liability of collective entities for acts prohibited under penalty] (PDF). Parliament of Poland (in Polish). 29 January 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

[Anyone] who, in public and against the facts, ascribes to the Polish Nation or to the Polish State, responsibility or co-responsibility for Nazi crimes committed by the Third Reich,< ...> or who otherwise grossly reduces the responsibility of the actual perpetrators of said crimes, is subject to a fine or [to] imprisonment for up to 3 years. < ...> No offense referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2 shall have been committed if the act was performed as part of artistic or scholarly activity.

- "Israel and Poland try to tamp down tensions after Poland's 'death camp' law sparks Israeli outrage". The Washington Post. 28 January 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Heller, Jeffrey; Goettig, Marcin (28 January 2018). "Israel and Poland clash over proposed Holocaust law". Reuters. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Katz, Brigit (29 January 2018). "The Controversy Around Poland's Proposed Ban on the Term 'Polish Death Camps'". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Fulbright, Alexander (27 June 2018). "Netanyahu takes credit after Poland amends Holocaust law, says dispute now over". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Collaboration and Complicity during the Holocaust". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 1 May 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Leslie, R. F. (1983). The History of Poland Since 1863. Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-521-27501-9.

- https://www.ushmm.org/collections/bibliography/poles

- Tonini, Carla (April 2008). "The Polish underground press and the issue of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers, 1939–1944". European Review of History / Revue Européenne d'Histoire. 15 (2): 193–205. doi:10.1080/13507480801931119.

- Friedrich, Klaus-Peter (Winter 2005). "Collaboration in a "Land without a Quisling": Patterns of Cooperation with the Nazi German Occupation Regime in Poland during World War II". Slavic Review. 64 (4): 711–746. doi:10.2307/3649910. JSTOR 3649910.

- Dybicz, Paweł (2012). "Wcieleni do Wehrmachtu - rozmowa z prof. Ryszardem Kaczmarkiem" ['Conscripted into the Wehrmacht' - interview with Prof. Ryszard Kaczmarek]. Przegląd (in Polish). No. 38. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Gumkowski, Janusz; Leszczynski, Kazimierz (1961). "Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe". Poland under Nazi Occupation. Warsaw: Polonia Publishing House. pp. 7–33, 164–178. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Geyer, Michael (2009). Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared. Cambridge University Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0-521-89796-9.

- Connelly, John (Winter 2005). "Why the Poles Collaborated so Little: And Why That Is No Reason for Nationalist Hubris". Slavic Review. 64 (4): 771–781. doi:10.2307/3649912. JSTOR 3649912.

- "Polish Resistance and Conclusions". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Berendt, Grzegorz (24 February 2017). "Opinion: The Polish People Weren't Tacit Collaborators With Nazi Extermination of Jews". Haaretz.

- Kermish, Joseph (1989). "The activities of the Council for Aid to Jews ("Zegota") in Occupied Poland". In Marrus, Michael Robert (ed.). The Nazi Holocaust. Part 5: Public Opinion and Relations to the Jews in Nazi Europe. Walter de Gruyter. p. 499. ISBN 978-3-110970-449.

- Foxman, Abraham H. (12 June 2012). "Poland and the Death Camps: Setting The Record Straight". The Jewish Week.

- Lipshiz, Cnaan (28 January 2018). "It's complicated: Inaccuracies plague both sides of 'Polish death camps' debate". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Zajączkowski, Wacław (June 1988). Christian Martyrs of Charity. Washington, D.C.: S.M. Kolbe Foundation. pp. 152–178. ISBN 978-0-945-28100-9.

- German military police in Grzegorzówka (p. 153) and in Hadle Szklarskie (p.154) extracted from two Jewish women the names of Poles who had been helping Jews, and 11 Polish men were murdered. In Korniaktów Forest, Łańcut County, a Jewish woman, discovered in an underground shelter, revealed the whereabouts of the Polish family who had been feeding her, and the whole family were murdered (p. 167). In Jeziorko, Łowicz County, a Jewish man betrayed all the Polish rescuers known to him, and 13 Poles were murdered by the German military police (p. 160). In Lipowiec Duży (Biłgoraj County), a captured Jew led the Germans to his saviors, and 5 Poles were murdered, including a 6-year-old child, and their farm was burned (p. 174). On a train to Kraków, the Żegota woman courier who was smuggling four Jewish women to safety was shot dead when one of the Jewish women lost her nerve (p. 170).

- Żarski-Zajdler, Władysław (1968). Martyrologia ludności żydowskiej i pomoc społeczeństwa polskiego [The Martyrology of the Jews, and Aid Given to Them by Poles]. Warsaw: ZBoWiD. p. 16.

- Furth, Hans G. (June 1999). "One Million Polish Rescuers of Hunted Jews?". Journal of Genocide Research. 1 (2): 227–232. doi:10.1080/14623529908413952.

- Richard C. Lukas, 1989.

- "Names of Righteous by Country". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Chefer, Chaim (1996). "Registry of over 700 Polish citizens killed while helping Jews During the Holocaust". Holocaust Forgotten. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- Lukas, Richard C. (1989). Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust. University Press of Kentucky. p. 13. ISBN 978-0813116921.

- "Canadian CTV Television censured for inaccurate and unfair reporting in referring to "Polish ghetto" and "Polish camp of Treblinka"". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. 13 June 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Ware, Doug G. (17 August 2016). "Poland may criminalize term 'Polish death camp' to describe Nazi WWII Holocaust sites". UPI. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Lapid: Poland was complicit in the Holocaust, new bill 'can't change history'". The Times of Israel. 27 January 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (2005). "Poland World War II casualties". Project InPosterum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- Łuczak, Czesław (1994). "Szanse i trudności bilansu demograficznego Polski w latach 1939–1945". Dzieje Najnowsze (1994/2).

- "Opinion: 'Polish death camps'". The Washington Post. 31 January 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Opinion: Poland's Holocaust Blame Bill". The New York Times. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "Fury in Israel as Poland proposes ban on referring to Nazi death camps as 'Polish'". The Daily Telegraph. 28 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "White House apologizes for Obama's 'Polish death camp' gaffe". The Times of Israel. 30 May 2012.

- "Interview with the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland, Prof. Adam Daniel Rotfeld". Rzeczpospolita. 25 January 2005. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008.

- Karski, Jan (14 October 1944). "Polish Death Camp". Collier's. pp. 18–19, 60–61.

- Karski, Jan (22 February 2013). Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World. Georgetown University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-58901-983-6.

- "The real source of misnomer "Polish Death Camps" – Jacek Gancarson MS, Natalia Zaytseva PhD – Justice For Polish Victims". Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Jak przypisano Janowi Karskiemu "polski obóz śmierci"?" (in Polish). Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Contemporary Jewish Record (American Jewish Committee), 1945, vol. 8, p. 69. Quote: "Most of the 27,000 Jews of Thrace ... were deported to Polish death camps."

- Jewish War Veterans of the United States of America 1945, vol. 14, no. 12. Quote: "2,000 Greek Jews repatriated from Polish death camps."

- The Palestine Yearbook and Israeli Annual (Zionist Organization of America) 1945, p. 337. Quote: "3,000,000 were foreign Jews brought to Polish death camps."

- Weinstock, Eugene (1947). Beyond the Last Path. New York: Boni & Gaer. p. 43.

- Nałkowska, Zofia (2000). Medallions. Northwestern University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8101-1743-3.

Not tens of thousands, not hundreds of thousands, but millions of human beings underwent manufacture into raw materials and goods in the Polish death camps.

- Lebovic, Matt (26 February 2016). "Do the words 'Polish death camps' defame Poland? And if so, who's to blame?". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Polskie czy niemieckie obozy zagłady?" [Polish or German extermination camps?]. Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu (in Polish). 23 July 2004.

- Wawrzyńczak, Marcin (14 August 2009). "'Polish Camps' in Polish Court". Gazeta Wyborcza. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Ruszył proces wobec "Die Welt" o "polski obóz koncentracyjny"". Wirtualna Polska. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- "As at Auschwitz, the gates of hell are built and torn down by human hearts". The Guardian. London. 23 December 2009. Archived from the original on 26 December 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- "Petition against 'Polish concentration camps'". Warsaw Business Journal. 3 November 2010. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- "Petition on German Concentration Camps". The Kosciuszko Foundation. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Canadian MPs defend Poland over 'Polish concentration camp' slur". Polskie Radio. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Były więzień Auschwitz skarży ZDF za "polskie obozy"" [Former Auschwitz prisoner complains to ZDF for "Polish camps"]. Interia (in Polish). 22 July 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Entschuldigung bei Karol Tendera" [Apology to Karol Tendera]. ZDF (in German). Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- "Death camps billboard in 1,000-mile trip". BBC News. 2 February 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Siegal, Allan M.; Connolly, William G. (2015). The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage: The Official Style Guide Used by the Writers and Editors of the World's Most Authoritative News Organization. Three Rivers Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-101-90544-9.

- "The New York Times bans "Polish concentration camps"". The Economist. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "AP Updates its Stylebook on Concentration Camps, Polish Foundation's Petition for Change has 300,000K Names". iMediaEthics. 16 February 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "White House: Obama misspoke by referring to 'Polish death camp' while honoring Polish war hero". The Washington Post. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- Siemaszko, Corky (1 June 2012). "Why the words 'Polish death camps' cut so deep". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- Obama, Barack (31 May 2012). "Letter to President Komorowski" (PDF). RMF FM. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Interwencje Przeciw 'Polskim Obozom'" [Interventions Against 'Polish Camps']. Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych (in Polish). 20 June 2006. Archived from the original on 1 August 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Poland's Foreign Minister is Jewish, but Most People Say It's No Big Deal". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 15 March 2005. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Government information on the Polish foreign policy presented by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prof. Adam Daniel Rotfeld, at the session of the Sejm on 21st January 2005". Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych. 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Akcja IPN: Mordowali "Niemcy", nie "naziści"" [IPN initiative: Murderers "German", not "Nazis"]. Interia (in Polish). 9 December 2008. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- Tran, Mark (27 June 2007). "Poles claim victory in battle to rename Auschwitz". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Spritzer, Dinah (27 April 2006). "Auschwitz Might Get Name Change". The Jewish Journal. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Yad Vashem for renaming Auschwitz". The Jerusalem Post. Associated Press. 11 May 2006. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- "UNESCO approves Poland's request to rename Auschwitz". Expatica. Expatica Communications B.V. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "World Heritage Committee approves Auschwitz name change". UNESCO World Heritage Committee. 28 June 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Watt, Nicholas (1 April 2006). "Auschwitz may be renamed to reinforce link with Nazi era". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Poland seeks Auschwitz renaming". BBC News. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Tran, Mark (27 June 2007). "Poles claim victory in battle to rename Auschwitz". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Selk, Avi (27 January 2018). "Analysis: It could soon be a crime to blame Poland for Nazi atrocities, and Israel is appalled". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Israeli politicians, survivors blast Polish Holocaust law". Ynet. Associated Press. 1 February 2018.

- "Poland Must Acknowledge Anti-Semitism, Wiesenthal Center's Founder Says". Bloomberg.com. 2 March 2018.

- Republic of Poland, Dziennik ustaw z 2016 roku, poz. 1575 (Register of Statutes, 2016, item 1575).

- Landau, Noa; Aderet, Ofer (1 February 2018). "Amid Holocaust Bill Spat With Israel, Polish State Media Suggests: Why Not 'Jewish Death Camps'?". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Gera, Vanessa (31 January 2018). "Polish TV riposte to Holocaust bill criticism: Auschwitz was 'Jewish death camp'". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Gera, Vanessa (30 January 2018). "Israeli criticism sparks anti-Jewish remarks in Polish media". Associated Press News. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "President says Poland did not take part in the Holocaust". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Pawlak, Justyna; Kelly, Lidia (31 January 2018). "Polish lawmakers back Holocaust bill, drawing Israeli outrage, U.S. concern". Reuters UK. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Hacohen, Hagay (12 February 2018). "Why is the Polish government targeting Israeli web users?". The Jerusalem Post.

- Maiberg, Emanuel (13 February 2018). "YouTube Keeps Serving Me Ads for Poland's 'Holocaust Law'". Vice.

- "Catholic, Jewish leaders in Poland seek to reduce tensions". The Washington Post. 15 March 2018.

- לפיד, יאיר (27 January 2018). "I utterly condemn the new Polish law which tries to deny Polish complicity in the Holocaust. It was conceived in Germany but hundreds of thousands of Jews were murdered without ever meeting a German soldier. There were Polish death camps and no law can ever change that". @yairlapid. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Israel criticises Polish Holocaust law". BBC News. 28 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Eglash, Ruth; Selk, Avi (28 January 2018). "It could soon be a crime to blame Poland for Nazi atrocities, and Israel is appalled". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Weinbaum, Laurence (21 April 2015). "Confronting chilling truths about Poland's wartime history". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Borschel-Dan, Amanda (8 February 2018). "Complicity of Poles in the deaths of Jews is highly underestimated, scholars say". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Weinbaum, Laurence (1998), Polish Jews: A Postscript to the 'Final Chapter' - Policy Study No. 14, Institute of the World Jewish Congress, Jerusalem.

- "Yad Vashem Response to the Law Passed in Poland Yesterday". Yad Vashem. 27 January 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Nahshon, Emmanuel [@EmmanuelNahshon] (29 January 2018). "Dear Polish followers - the issue is NOT the death camps" (Tweet). Retrieved 3 February 2018 – via Twitter.

- Avineri, Shlomo (5 March 2018). "Opinion: Holocaust Trips to Poland for Israeli Youth Should Start in Germany". Haaretz. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Aderet, Ofer (12 April 2018). "Israeli President to Polish Counterpart: We Cannot Deny That Poland and Poles Participated in Holocaust". Haaretz. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Harkov, Lahav (29 January 2018). "How I became public enemy No. 1 in Poland". The Jerusalem Post.

- Sommer, Allison Kaplan (28 January 2018). "I Used to Care About Polish Sensitivity to Charges of Holocaust Complicity. Not Anymore". Haaretz. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Netanyahu publicly flouts Poland's Holocaust Law".

- "Letter of support to Polish President Duda" (PDF). Polish American Congress. 12 February 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Commentary: Poland's Holocaust faux pas". Reuters. 23 February 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Matysiak, Jacek K. (17 February 2018). "Polska i Izrael, czara goryczy ..." [Poland and Israel: Cup of Bitterness ...]. Gwiazda Polarna. 109 (4). pp. 1, 7–8.

- Masters, James; Mortensen, Antonia (20 February 2018). "Poland's Jewish groups say Jews feel unsafe since new Holocaust law". CNN. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Oświadczenie organizacji żydowskich do opinii publicznej / Open statement of Polish Jewish organizations to the public opinion". Jewish.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- "Znany varsavianista pochodzenia żydowskiego odsyła ambasador Izraela wyróżnienie" [Well-known Jewish-Polish Historian of Warsaw Returns Prize to Israeli Ambassador]. Gwiazda Polarna. 109 (5). 3 March 2018. pp. 2 & 16.

- "AJC Opposes Polish Effort to Criminalize Claims of Holocaust Responsibility". American Jewish Committee. 27 January 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018 – via PRNewswire.

- Tibon, Amir (27 January 2018). "As Poland's New Holocaust Law Causes Storm, U.S. Urges 'Never Again' on Holocaust Remembrance Day". Haaretz. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Poland's Senate passes controversial Holocaust bill". BBC News. 1 February 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- @sigmargabriel (3 February 2018). "Ich habe 15 Jahre lang als Gruppenleiter Jugendreisen nach Auschwitz und Majdanek organisiert..." (Tweet) (in German). Retrieved 11 November 2018 – via Twitter.

- Landau, Noa; Aderet, Ofer (3 February 2018). "German FM Weighs in on Polish Holocaust Bill: Germany Alone Was Responsible for the Holocaust 'And No One Else'". Haaretz. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Zieve, Tamara (21 February 2018). "US Jewish Group Draws Fire for 'Polish Holocaust' Campaign". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Gera, Vanessa (21 February 2018). "US Jewish group withdraws Holocaust video offensive to Poles". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Applebaum, Anne (2 February 2018). "The stupidity and unenforceability of Poland's speech law". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: "Polish death camp" controversy |

- Truth about camps, website created by Institute of National Remembrance

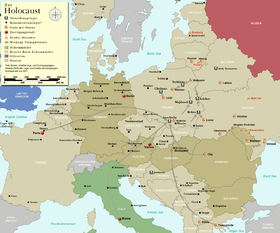

- Map of the German Death Camps on occupied Polish territories.

- Concentration camps' functionaries and biographical notes and witness' accounts created by Institute of National Remembrance

- "In Response to Comments Regarding Death Camps in Poland". Yad Vashem. 29 January 2015.

- Glenday, James (24 February 2018). "What's It Like to Live next to the World's Most Notorious Concentration Camp". Australian Broadcasting Corporation News.