Urnfield culture

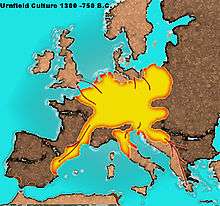

The Urnfield culture (c. 1300 BC – 750 BC) was a late Bronze Age culture of central Europe, often divided into several local cultures within a broader Urnfield tradition. The name comes from the custom of cremating the dead and placing their ashes in urns which were then buried in fields. Over much of Europe, the Urnfield culture followed the Tumulus culture and was succeeded by the Hallstatt culture.[1] Linguistic evidence suggests that the people of this area spoke a form of Italo-Celtic,[2] and/or early Celtic, perhaps originally Proto-Celtic.[1][3]

| |

| Geographical range | Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age Europe |

| Dates | c. 1300 — c. 750 BC |

| Major sites | Burgstallkogel (Sulm valley) |

| Preceded by | Tumulus culture |

| Followed by | Hallstatt culture, Proto-Villanovan culture |

| Bronze Age |

| ↑ Chalcolithic |

|

Africa, Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC)

Indian subcontinent (c. 3300–1200 BC) Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

East Asia (c. 3100–300 BC) |

|

| ↓Iron Age |

Chronology

It is believed that in some areas, such as in southwestern Germany, the Urnfield culture was in existence around 1200 BC (beginning of Hallstatt A or Ha A), but the Bronze D Riegsee-phase already contains cremations. As the transition from the middle Bronze Age to the Urnfield culture was gradual, there are questions regarding how to define it.

The Urnfield culture covers the phases Hallstatt A and B (Ha A and B) in Paul Reinecke's chronological system, not to be confused with the Hallstatt culture (Ha C and D) of the following Iron Age. This corresponds to the Phases Montelius III-IV of the Northern Bronze Age. Whether Reinecke's Bronze D is included varies according to author and region.

The Urnfield culture is divided into the following sub-phases (based on Müller-Karpe sen.):

| date BC | |

|---|---|

| BzD | 1300–1200 |

| Ha A1 | 1200–1100 |

| Ha A2 | 1100–1000 |

| HaB1 | 1000–800 |

| HaB2 | 900–800 |

| Ha B3 | 800–750 |

The existence of the Ha B3-phase is contested, as the material consists of female burials only. As can be seen by the arbitrary 100-year ranges, the dating of the phases is highly schematic. The phases are based on typological changes, which means that they do not have to be strictly contemporaneous across the whole distribution. All in all, more radiocarbon and dendro-dates would be highly desirable.

Origin

The Urnfield culture grew from the preceding Tumulus culture.[1] The transition is gradual, in the pottery as well as the burial rites.[1] In some parts of Germany, cremation and inhumation existed simultaneously (facies Wölfersheim). Some graves contain a combination of Tumulus-culture pottery and Urnfield swords (Kressbronn, Bodenseekreis) or Tumulus culture incised pottery together with early Urnfield types (Mengen). In the North, the Urnfield culture was only adopted in the HaA2 period. 16 pins deposited in a swamp in Ellmoosen (Kr. Bad Aibling, Germany) cover the whole chronological range from Bronze B to the early Urnfield period (Ha A). This demonstrates a considerable ritual continuity. In the Loire, Seine and Rhône, certain fords contain deposits from the late Neolithic onwards up to the Urnfield period.

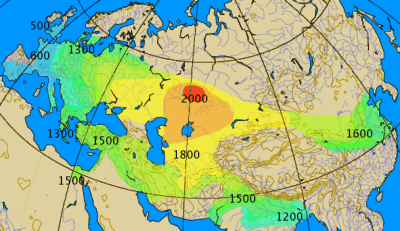

The origins of the cremation rite are commonly believed to be in Hungary, where it was widespread since the first half of the second millennium BC.[4] The neolithic Cucuteni–Trypillia culture of modern-day northeastern Romania and Ukraine were also practicing cremation rituals as early as approximately 5500 BC. Some cremations begin to be found in the Proto-Lusatian and Trzciniec culture.

Distribution and local groups

The Urnfield culture was located in an area stretching from western Hungary to eastern France, from the Alps to near the North Sea. Local groups, mainly differentiated by pottery, include:

- Knovíz culture in western and Northern Bohemia, southern Thuringia and North-eastern Bavaria

- Milavce culture in southeastern Bohemia

- Unstrut culture in Thuringia, a mixture between Knovíz-culture and the South-German Urnfield culture

- Lusatian culture in northern Bohemia, Lusatia and Poland

- Northeast-Bavarian Group, divided into a lower Bavarian and an upper Palatinate group

- Lower-Main-Swabian group in southern Hesse and Baden-Württemberg, including the Marburger, Hanauer, lower Main and Friedberger facies

- Rhenish-Swiss group in Rhineland-Palatinate, Switzerland and eastern France, (abbreviated RSFO in French)

- Lower Hessian Group

- North-Netherlands-Westphalian group

- Northwest-Group in the Dutch Delta region

Middle-Danube Urnfield culture

- Velatice-Baierdorf in Moravia and Austria

- Čaka in western Slovakia

- Gáva culture

- Piliny culture

- Kyjatice culture

- Makó culture

Sometimes the distribution of artifacts belonging to these groups shows sharp and consistent borders, which might indicate some political structures, like tribes. Metalwork is commonly of a much more widespread distribution than pottery and does not conform to these borders. It may have been produced at specialised workshops catering for the elite of a large area.

Important French cemeteries include Châtenay and Lingolsheim (Alsace). An unusual earthwork was constructed at Goloring near Koblenz in Germany.

Related cultures

The central European Lusatian culture forms part of the Urnfield tradition, but continues into the Iron Age without a notable break.

The Piliny culture in northern Hungary and Slovakia grew from the Tumulus culture, but used urn burials as well. The pottery shows strong links to the Gáva culture, but in the later phases, a strong influence of the Lusatian culture is found. In Italy the late Bronze Age Canegrate and Proto-Villanovan cultures and the early Iron Age Villanovan culture show similarities with the urnfields of central Europe. Urnfields are found in the French Languedoc and Catalonia from the 9th to 8th centuries. The change in burial custom was most probably influenced by developments further east.

The Golasecca culture in northern Italy developed with continuity from the Canegrate culture.[3][5] Canegrate represented a completely new cultural dynamic to the area expressed in pottery and bronzework, making it a typical western example of the Urnfield culture, in particular the Rhine-Switzerland-Eastern France (RSFO) Urnfield culture.[3][5] The Lepontic Celtic language inscriptions of the area show the language of the Golasecca culture was clearly Celtic making it probable that the 13th-century BC language of at least the RSEF area of the western urnfields was also Celtic or a precursor to it.[3][5]

Placename evidence has also been used to point to an association of the Urnfield materials with a Proto-Celtic language group in central Europe, and it has been argued that it was the ancestral culture of the Celts.[6] The Urnfield layers of the Hallstatt culture, Ha A and Ha B, are succeeded by the Iron Age "Hallstatt period" proper (Ha C and Ha D, 8th-6th centuries BC), associated with the early Celts; Ha D is in turn succeeded by the La Tène culture, the archaeological culture associated with the Continental Celts of antiquity.

The influence of the Urnfield culture spread widely and found its way to the northeastern Iberian coast, where the nearby Celtiberians of the interior adapted it for use in their cemeteries.[7] Evidence for east-to-west early Urnfield (Bronze D-Hallstatt A) elite contacts such as rilled-ware, swords and crested helmets has been found in the southwest of the Iberian peninsula.[8] The appearance of such elite status markers provides the simplest explanation for the spread of Celtic languages in this area from prestigious, proto-Celtic, early-Urnfield metalworkers.[8]

Migrations

The numerous hoards of the Urnfield culture and the existence of fortified settlements (hill forts) were taken as evidence for widespread warfare and upheaval by some scholars. Written sources describe several collapses and upheavals in the Eastern Mediterranean, Anatolia and the Levant around the time of the Urnfield origins:

- End of the Mycenean culture with a conventional date of c. 1200 BC

- Destruction of Troy VI c. 1200 BC

- Battles of Ramses III against the Sea Peoples, 1195–1190 BC

- End of the Hittite empire 1180 BC

- Settlement of the Philistines in Canaan c. 1170 BC

Some scholars, among them Wolfgang Kimmig and P. Bosch-Gimpera have postulated a Europe-wide wave of migrations. The so-called Dorian invasion of Greece was placed in this context as well (although more recent evidence suggests that the Dorians moved in 1100 BC into a post Mycenaean vacuum, rather than precipitating the collapse). Better methods of dating have shown that these events are not as closely connected as once thought. [citation needed]

More recently Robert Drews, after having reviewed and dismissed the migration hypothesis, has suggested that the observed cultural associations may be in fact partly explained as the result of a new kind of warfare based upon the slashing Naue II sword,[9] and with bands of infantry replacing chariots in warfare. Drews suggests that the political instability that this brought to centralised states based upon maryannu chariotry caused the breakdown of these polities.

Settlements

The number of settlements increased sharply in comparison with the preceding Tumulus culture. Unfortunately, few have been comprehensively excavated. Fortified settlements, often on hilltops or in river-bends, are typical for the Urnfield culture. They are heavily fortified with dry-stone or wooden ramparts. Excavations of open settlements are rare, but they show that large 3-4 aisled houses built with wooden posts and wall of wattle and daub were common. Pit dwellings are known as well; they might have served as cellars.

Open settlements

The houses were one or two-aisled. Some were quite small, 4.5 m × 5 m at the Runder Berg (Urach, Germany), 5-8m long in Künzig (Bavaria, Germany), others up to 20 m long. They were built with wooden posts and walls of wattle and daub. At the Velatice-settlement of Lovčičky (Moravia, Czech Republic) 44 houses have been excavated. Large bell shaped storage pits are known from the Knovíz-culture. The settlement of Radonice (Louny) contained over 100 pits. They were most probably used to store grain and demonstrate a considerable surplus-production.

.jpg)

Pile dwellings

On lakes of southern Germany and Switzerland, numerous pile dwellings were constructed. They consist either of simple one-room houses made of wattle and daub, or log-built. The settlement at Zug, Switzerland, was destroyed by fire and gives important insights into the material culture and the settlement organisation of this period. It has yielded a number of dendro-dates as well.

Fortified settlements

Fortified hilltop settlements become common in the Urnfield period. Often a steep spur was used, where only part of the circumference had to be fortified. Depending on the locally available materials, dry-stone walls, gridded timbers filled with stones or soil or plank and palisade type pfostenschlitzmauer fortifications were used. Other fortified settlements used river-bends and swampy areas.

At the hill fort of Hořovice near Beroun (CR), 50 ha were surrounded by a stone wall. Most settlements are much smaller. Metal working is concentrated in the fortified settlements. On the Runder Berg near Urach, Germany, 25 stone moulds have been found.

Hillforts are interpreted as central places. Some scholars see the emergence of hill forts as a sign of increased warfare. Most hillforts were abandoned at the end of the Bronze Age.

As far as we know, there are no special dwellings for an upper class, but few settlements have been excavated to any extent. In the Franche-Comté, caves were used as dwellings, perhaps in times of trouble.

Examples of fortified settlements include the Heunischenburg, Bullenheimer Berg, Bernstorf, Hesselberg, Bürgstadter Berg, Schellenburg, Farrenberg (all in Germany), the Oberleiserberg in Austria, Plešivec in the Czech Republic, and Corneşti-Iarcuri in Romania.

Material culture

Pottery

The pottery is normally well made, with a smooth surface and a normally sharply carinated profile. Some forms are thought to imitate metal prototypes. Biconical pots with cylindrical necks are especially characteristic. There is some incised decoration, but a large part of the surface was normally left plain. Fluted decoration is common. In the Swiss pile dwellings, the incised decoration was sometimes inlaid with tin foil. Pottery kilns were already known (Elchinger Kreuz, Bavaria), as is indicated by the homogeneous surface of the vessels as well. Other vessels include cups of beaten sheet-bronze with riveted handles (type Jenišovice) and large cauldrons with cross attachments. Wooden vessels have only been preserved in waterlogged contexts, for example from Auvernier (Neuchâtel), but may have been quite widespread.

Tools and weapons

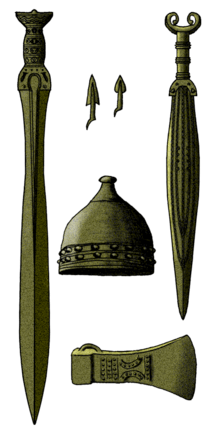

The early Urnfield period (1300 BC) was a time when the warriors of central Europe could be heavily armored with body armor, helmets and shields all made of bronze, most likely borrowing the idea from Mycenaean Greece.[10]

The leaf-shaped Urnfield sword could be used for slashing, in contrast to the stabbing-swords of the preceding Tumulus culture. It commonly possessed a ricasso. The hilt was normally made from bronze as well. It was cast separately and consisted of a different alloy. These solid hilted swords were known since Bronze D (Rixheim swords). Other swords have tanged blades and probably had a wood, bone, or antler hilt. Flange-hilted swords had organic inlays in the hilt. Swords include Auvernier, Kressborn-Hemigkofen, Erbenheim, Möhringen, Weltenburg, Hemigkofen and Tachlovice-types.

Protective gear like shields, cuirasses, greaves and helmets are extremely rare and almost never found in burials. The best-known example of a bronze shield comes from Plzeň in Bohemia and has a riveted handhold. Comparable pieces have been found in Germany, Western Poland, Denmark, Great Britain and Ireland. They are supposed to have been made in upper Italy or the Eastern Alps and imitate wooden shields. Irish bogs have yielded examples of leather shields (Clonbrinn, Co. Wexford). Bronze cuirasses are known since Bronze D (Čaka, grave II, Slovakia).

Complete bronze cuirasses have been found in Saint Germain du Plain, nine examples, one inside the other, in Marmesse, Haute Marne (France), fragments in Albstadt-Pfeffingen (Germany). Bronze dishes (phalerae) may have been sewn on a leather armour. Greaves of richly decorated sheet-bronze are known from Kloštar Ivanić (Croatia) and the Paulus cave near Beuron (Germany).

Chariots

About a dozen wagon-burials of four wheeled wagons with bronze fittings are known from the early Urnfield period. They include Hart an der Altz (Kr. Altötting), Mengen (Kr. Sigmaringen), Poing (Kr. Ebersberg), Königsbronn (Kr. Heidenheim) from Germany and St. Sulpice (Vaud), Switzerland. In Alz, the chariot had been placed on the pyre, pieces of bone are attached to the partially melted metal of the axles. Bronze (one-part) bits appear at the same time. Two-part horse bits are only known from late Urnfield contexts and may be due to eastern influence. Wood- and bronze spoked wheels are known from Stade (Germany), a wooden spoked wheel from Mercurago, Italy. Wooden dish-wheels have been excavated at Corcelettes, Switzerland and the Wasserburg Buchau, Germany (diameter 80 cm).

In Milavče near Domažlice, Bohemia, a four-wheeled miniature bronze wagon bearing a large cauldron (diameter 30 cm) contained a cremation. This exceptionally rich burial was covered by a barrow. The wagon from Acholshausen (Bavaria) comes from a male burial.

Such wagons are known from the Nordic Bronze Age as well. The Skallerup wagon, Denmark, contained a cremation as well. At Pekatel (Kr. Schwerin) in Mecklenburg a cauldron-wagon and other rich grave goods accompanied an inhumation under a barrow (Montelius III/IV). Another example comes from Ystad in Sweden. South-eastern European examples include Kanya in Hungary and Orăştie in Romania. Clay miniature wagons, sometimes with waterfowl were known there since the middle Bronze Age (Dupljaja, Vojvodina, Serbia).

The Lusatian chariot from Burg (Brandenburg, Germany) has three wheels on a single axle, on which waterfowl perch. The grave of Gammertingen (Kr. Sigmaringen, Germany) contained two socketed horned applications that probably belonged to a miniature wagon comparable to the Burg example, together with six miniature spoked wheels.

- Miniature bronze wagon from Acholshausen in Germany.

Bronze wheels from Hassloch in Germany, 900-800 BC

Bronze wheels from Hassloch in Germany, 900-800 BC Bronze chariot wheel from Arokalja in Romania, with water bird decoration.

Bronze chariot wheel from Arokalja in Romania, with water bird decoration.

Hoards

Hoards are very common in the Urnfield culture. The custom is abandoned at the end of the Bronze Age. They were often deposited in rivers and wet places like swamps. As these spots were often quite inaccessible, they most probably represent gifts to the gods. Other hoards contain either broken or miscast objects that were probably intended for reuse by bronze smiths. As Late Urnfield hoards often contain the same range of objects as earlier graves, some scholars interpret hoarding as a way to supply personal equipment for the hereafter. In the river Trieux, Côtes du Nord, complete swords were found together with numerous antlers of red deer that may have had a religious significance as well.

Crescent shaped Urnfield culture razor

Crescent shaped Urnfield culture razor Gold necklace from Han-sur-Lesse in Belgium, 1000-900 BC

Gold necklace from Han-sur-Lesse in Belgium, 1000-900 BC

Iron

An iron ring from Vorwohlde (Kr. Grafschaft Diepholz, Germany) dating to the 15th century BC is the earliest evidence of iron in Central Europe. During the late Bronze Age, Iron was used to decorate the hilts of swords (Schwäbisch-Hall-Gailenkirchen, Unterkrumbach, Kr. Hersbruck) and knives (Dotternhausen, Plettenberg, Germany) and pins. The use of iron for weapons and domestic items in Europe only started in the following Hallstatt culture. The widespread use of iron for tools only occurred in the late Iron Age La Tène culture.

Economy

Cattle, pigs, sheep and goats were kept, as well as horses, dogs and geese. The cattle were rather small, with a height of 1.20 m at the withers. Horses were not much bigger with a mean of 1.25 m.

Forest clearance was intensive in the Urnfield period. Probably open meadows were created for the first time, as shown by pollen analysis. This led to increased erosion and sediment-load of the rivers.

Wheat and barley were cultivated, together with pulses and the horse bean. Poppy seeds were used for oil or as a drug. Millet and oats were cultivated for the first time in Hungary and Bohemia, rye was already cultivated, further west it was only a noxious weed. Flax seems to have been of reduced importance, maybe because mainly wool was used for clothes. Hazel nuts, apples, pears, sloes and acorns were collected. Some rich graves contain bronze sieves that have been interpreted as wine-sieves (Hart an der Alz). This beverage would have been imported from the South, but supporting evidence is lacking. In the lacustrine settlement of Zug, remains of a broth made of spelt and millet have been found. In the lower-Rhine urnfields, leavened bread was often placed on the pyre and burnt fragments have thus been preserved.

Wool was spun (finds of spindle whorls are common) and woven on the warp-weighted loom; bronze needles (Unteruhldingen) were used for sewing.

There is some suggestion that the Urnfield culture is associated with a wetter climatic period than the earlier Tumulus cultures. This may be associated with the diversion of the mid-latitude winter storms north of the Pyrenees and the Alps, possibly associated with drier conditions in the Mediterranean basin.

Urnfield numerals

Various large hoards of sickles have been excavated across central Europe, which feature a range of cast markings that have been interpreted in different ways. An analysis of the Frankleben hoard from central Germany found that markings on the sickles constituted a numeral system related to the lunar calendar. According to the Halle State Museum of Prehistory:

“Many sickles carry line-shaped markings. The scope and order of these brands follows a defined pattern. This sign language can be interpreted as a pre-form of a writing system. There are two types of symbols: line-shaped marks below the button and marks at the angle or at the base of the sickle body. The archaeologist Christoph Sommerfeld examined the rules and realized that the casting marks are composed of one to nine ribs. After four left-hand, individually counted strokes there follows a bundle as a group of five on the right side. This creates a counting system that reaches to 29. The Synodic Moon orbit lasts 29 days or nights. This number and the lunar shape of the sickle suggest that the stroke groups should be interpreted as calendar pages, as a point in the monthly cycle. The sickle marks are the oldest known sign system in Central Europe.”[11]

Gold Hats

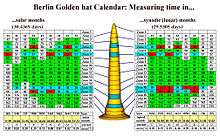

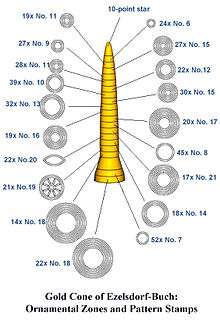

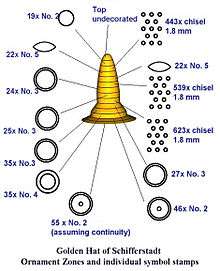

Four elaborate cone-shaped hats made from thin sheets of gold have been found in Germany and France, dated to 1200-800 BC. It's thought that they may have been worn as ceremonial hats by ‘king-priests’ or oracles.[12]

The gold cones are covered in bands of ornaments along their whole length and extent. The ornaments - mostly disks and concentric circles, sometimes wheels, crescents, pointed oval shapes and triangles - were punched using stamps, rolls or combs. Analysis of the Berlin Gold Hat has demonstrated that its ornaments form systematic patterns which represent the Metonic cycle of a lunisolar calendar. According to the historian Wilfried Menghin:

“The symbols on the hat are a logarithmic table which enables the movements of the sun and the moon to be calculated in advance.”[13]

Berlin Gold Hat, Neues museum

Berlin Gold Hat, Neues museum Calendrical function of the Berlin Gold Hat

Calendrical function of the Berlin Gold Hat The Gold Hat of Ezelsdorf-Buch. Schematic depiction of ornamention and stamps

The Gold Hat of Ezelsdorf-Buch. Schematic depiction of ornamention and stamps The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt. Schematic depiction of ornamention and stamps.

The Golden Hat of Schifferstadt. Schematic depiction of ornamention and stamps.

Funerary customs

Graves

In the Tumulus period, multiple inhumations under barrows were common, at least for the upper levels of society. In the Urnfield period, inhumation and burial in single flat graves prevails, though some barrows exist.

In the earliest phases of the Urnfield period, man-shaped graves were dug, sometimes provided with a stone lined floor, in which the cremated remains of the deceased were spread. Only later, burial in urns became prevalent. Some scholars speculate that this may have marked a fundamental shift in people's beliefs or myths about life and the afterlife.

The size of the urnfields is variable. In Bavaria, they can contain hundreds of burials, while the largest cemetery in Baden-Württemberg in Dautmergen has only 30 graves. The dead were placed on pyres, covered in their personal jewellery, which often shows traces of the fire and sometimes food-offerings. The cremated bone-remains are much larger than in the Roman period, which indicates that less wood was used. Often, the bones have been incompletely collected. Most urnfields are abandoned with the end of the Bronze Age, only the Lower Rhine urnfields continue in use in the early Iron Age (Ha C, sometimes even D).

The cremated bones could be placed in simple pits. Sometimes the dense concentration of the bones indicates a container of organic material, sometimes the bones were simply shattered.

If the bones were placed in urns, these were often covered by a shallow bowl or a stone. In a special type of burial (bell-graves) the urns are completely covered by an inverted larger vessel. As graves rarely overlap, they may have been marked by wooden posts or stones. Stone-pacing graves are typical of the Unstrut group.

Grave gifts

The urn containing the cremated bones is often accompanied by other, smaller ceramic vessels, like bowls and cups. They may have contained food. The urn is often placed in the centre of the assemblage. Often, these vessels have not been placed on the pyre. Metal grave gifts include razors, weapons that often have been deliberately destroyed (bent or broken), bracelets, pendants and pins. Metal grave gifts become rarer towards the end of the Urnfield culture, while the number of hoards increase. Burnt animal bones are often found, they may have been placed on the pyre as food. The marten bones in the grave of Seddin may have belonged to a garment (pelt). Amber or glass beads (Pfahlbautönnchen) are luxury items.

Upper-class graves

Upper-class burials were placed in wooden chambers, rarely stone cists or chambers with a stone-paved floor and covered with a barrow or cairn. The graves contain especially finely made pottery, animal bones, usually pork, sometimes gold rings or sheets, in exceptional cases miniature wagons. Some of these rich burials contain the remains of more than one person. In this case, women and children are normally seen as sacrifices. Until more is known about the status distribution and the social structure of the late Bronze Age, this interpretation should be viewed with caution, however. Towards the end of the Urnfield period, some bodies were burnt in situ and then covered by a barrow, reminiscent of the burial of Patroclus as described by Homer and the burial of Beowulf (with the additional ship burial element). In the early Iron Age, inhumation became the rule again.

Cult

The Kyffhäuser caves in Thuringia contain headless skeletons and split human and animal bones that have been interpreted as sacrifices. Other deposits include grain, knotted vegetable fibres and hair and bronze objects (axes, pendants and pins). The Ith-caves (Lower Saxony) have yielded comparative material.

In the Knovíz-culture, human bones with cut-marks and traces of burning have been found in settlement pits. Moon-shaped clay fire dogs are thought to have a religious significance, as well as crescent shaped razors.

An obsession with waterbirds is indicated by numerous pictures and three-dimensional representations. Combined with the hoards deposited in rivers and swamps, it indicates religious beliefs connected with water. This has led some scholars to believe in serious droughts during the late Bronze Age. Sometimes the water-birds are combined with circles, the so-called sun-barque-motif.

See also

- Beaker culture

- Sorothaptic language

- Urnfield culture numerals

References

- Chadwick and Corcoran, Nora and J.X.W.P. (1970). The Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 28–29.

- Peter Schrijver, 2016, "Italo-Celtic Linguistic Unity", in John T. Koch & Barry Cunniffe, Celtic From the West 3: Atlantic Europe in the Metal Ages: questions of shared language. Oxford, England; Oxbow Books, pp. 9, 489–502.

- Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 93–100.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1965). Bronze age cultures in Central and Eastern Europe. Mouton Publishers. pp. 274–298.

- Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). p. 24.

- Chadwick with Corcoran, Nora with J.X.W.P. (1970). The Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 28–33.

- Cremin, Aedeen (1992). The Celts in Europe. Sydney, Australia: Sydney Series in Celtic Studies 2, Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Sydney. pp. 59–60. ISBN 0-86758-624-9.

- Koch, John T. (2013). Celtic from the West 2 - Prologue: The Earliest Hallstatt Iron Age cannot equal Proto-Celtic. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-84217-529-3.

- Drews. R (1993) "The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C." Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-04811-8

- Gimbutas, Marija (2011-08-25). Bronze Age cultures in Central and Eastern Europe. google.dk. ISBN 9783111668147.

- "Sickle Hoards" Halle State Museum of Prehistory

- 'Mysterious gold cones hats of ancient wizards' The Telegraph, 2002

- 'Mysterious gold cones hats of ancient wizards' The Telegraph, 2002

Bibliography

- J. M. Coles/A. F. Harding, The Bronze Age in Europe (London 1979).

- G. Weber, Händler, Kieger, Bronzegießer (Kassel 1992).

- Ute Seidel, Bronzezeit. Württembergisches Landesmuseum Stuttgart (Stuttgart 1995).

- Konrad Jażdżewski, Urgeschichte Mitteleuropas (Wrocław 1984)

- Association Abbaye de Daoulas (eds.), Avant les Celtes. L'Europe a l'age du Bronze (Daoulas 1988).

- Frans Theuws, Nico Roymans (eds.), Land and ancestors: cultural dynamics in the Urnfield period and the Middle Ages in the southern Netherlands, Amsterdam Archaeological Studies, Amsterdam University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-90-5356-278-9.

External links

![]()